Abstract

Purpose

In a comparative phase 3 study involving 1114 Japanese patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC), palonosetron (PALO) was found to be superior to granisetron (GRA) for the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in the delayed phase. This post hoc analysis of the phase 3 study evaluated the efficacy of PALO for the control of nausea.

Methods

The proportion of patients without nausea was assessed at 24-h intervals during the acute phase (0–24 h), delayed phase (24–120 h), and overall (0–120 h). No nausea rates were also evaluated by sex, type of chemotherapy (cisplatin or doxorubicin/epirubicin plus cyclophosphamide [AC/EC]), and age (<55 vs. ≥55 years). Nausea severity was categorized using a 4-point Likert scale (0 = no nausea to 3 = severe nausea).

Results

The proportion of patients without nausea was significantly higher in the PALO arm than in the GRA arm in the delayed phase (37.8 % vs. 27.2 %; p = 0.002) and overall (31.9 % vs. 25.0 %; p = 0.0117). When analyzed by stratification factors, the proportion of patients without nausea was significantly higher in the PALO arm in the delayed phase and overall in patients who were female, younger, or treated with cisplatin and in the delayed phase in patients who were older or treated with doxorubicin or epirubicin plus cyclophosphamide (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

PALO was more effective than GRA in prophylaxis of HEC-induced nausea in the delayed phase and overall. In addition, PALO was more effective than GRA in young and female patients, who are at high risk of CINV, both in the delayed phase and overall.

Keywords: 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, Palonosetron, Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, Highly emetic chemotherapy, Antiemetics

Introduction

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) causes distress in cancer patients and reduces their quality of life [1, 2]. The prophylaxis of CINV has greatly improved since the appearance of the 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonists (RAs) [3, 4] and the neurokinin 1 (NK1) RA aprepitant [4–6]. However, the prophylaxis of CINV is often suboptimal [7]. If appropriate antiemetic therapy is not provided, 70–80 % of patients receiving emetogenic chemotherapy will experience CINV [8]. Thus, the effective prophylaxis of CINV is a key aspect of patient care.

The current recommended standard of care (SoC) for CINV in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) is dexamethasone plus aprepitant and a 5-HT3 RA. For moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC), the recommended SoC is dexamethasone and a 5-HT3 RA with or without aprepitant, as recommended by a number of guidelines [9–13]. Although these guidelines are widely available, their use in clinical practice remains suboptimal [14]. In addition, first-generation 5-HT3 RAs, such as ondansetron and granisetron (GRA), are less effective for the treatment of CINV in the delayed phase than in the acute phase [4, 15, 16]. There is therefore an unmet need for more effective therapies to control CINV, which has led to the development of new-generation 5-HT3 RAs such as palonosetron (PALO).

PALO has a longer half-life, more potent binding, and unique molecular interactions with the 5-HT3 receptor in comparison with the first-generation 5-HT3 RAs [4]. PALO allosterically binds to the 5-HT3 receptors with positive cooperativity, which most likely triggers the internalization of these receptors, leading to persistent inhibition of their function [4]. In addition, PALO is able to inhibit 5-HT3/NK1 receptor signaling cross-talk, mediating the prophylaxis of delayed CINV in contradistinction to first-generation 5-HT3 RAs [4]. It has shown efficacy in the prophylaxis of CINV in the acute and delayed phases as well as overall in a number of clinical studies [17]. PALO has also been shown to be more effective than dolasetron [18] and ondansetron [19] in patients receiving MEC and more effective than ondansetron [20] in patients receiving HEC. Additionally, a recent retrospective study in almost 10,000 patients with breast or lung cancer treated with carboplatin or cisplatin showed that patients initiated and maintained on PALO had a significantly lower risk of CINV than patients receiving first-generation 5-HT3 RAs [21]. In a comparative phase 3 study of single-dose PALO and GRA, both administered with dexamethasone, involving 1114 Japanese patients receiving HEC, Saito et al. found that PALO was non-inferior to GRA for the control of CINV in the acute phase and superior to GRA in the delayed phase [22].

When evaluating treatments to control CINV, risk factors for CINV should be taken into consideration. The efficacy of CINV prophylaxis can be influenced by the chemotherapeutic regimen and the patient’s age, sex, and smoking history [23, 24]. Although a number of studies found that the efficacy of CINV prophylaxis was not affected by age [25–27], other studies reported contrasting results. Specifically, in women being treated for chemotherapy and receiving the 5-HT3 RA ondansetron combined with dexamethasone, acute CINV was better controlled in older patients (>45 years) and in patients receiving non-cisplatin-containing chemotherapy [28]. The 5-HT3 RA GRA has also been reported to be more effective in elderly patients [29]. A recent study aiming to identify CINV risk factors showed that non-habitual alcohol intake and younger age (<55 years) were risk factors for acute CINV and that female sex was a risk factor for both acute and delayed CINV [24].

In trials evaluating CINV treatments, to assess the occurrence of nausea is also important. Nausea is reported to have a greater negative effect on daily life than vomiting [1] and remains one of the most feared chemotherapy-related adverse events [8]. The challenges of controlling chemotherapy-induced nausea are greater than those for chemotherapy-induced vomiting, mostly because nausea is less well understood at the neurochemical level [30]. Therefore, many CINV treatments have been less successful for nausea control than for vomiting control [31, 32].

In a further analysis of the Japanese comparative phase 3 study conducted by Saito et al. [22], the efficacy of PALO for the control of nausea was evaluated in the overall population and in subgroups stratified according to sex, type of chemotherapy (cisplatin or doxorubicin/epirubicin plus cyclophosphamide [AC/EC]), and age (<55 or ≥55 years).

Patients and methods

Study design

Details of the study design have previously been published [22] (ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT00359567).

Nausea

Evaluation of nausea was a secondary endpoint. The proportion of patients without nausea was assessed daily (days 1–5), during the acute phase (0–24 h), delayed phase (24–120 h), and overall (0–120 h). In addition, the proportion of patients without nausea was assessed according to the stratification factors including sex, age (<55 or ≥55 years), and type of chemotherapy (cisplatin or AC/EC). Patient diaries were used to evaluate the degree of nausea in daily (24-h) intervals for 120 h after the start of chemotherapy. Nausea was defined as the feeling of being about to vomit. Nausea severity was categorized using a 4-point Likert scale (0 = no nausea, 1 = mild nausea, 2 = moderate nausea, and 3 = severe nausea) according to the subjective assessment of each patient.

Statistics

The efficacy analyses were based on the modified intention-to-treat (ITT) cohort, which included all randomized patients who received the study drugs and HEC. The proportion of patients without nausea was assessed during the acute phase, the delayed phase, the overall study period, and at 24-h intervals throughout the 120 h. Baseline characteristics of the modified ITT cohort were summarized descriptively. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze the proportion of patients without nausea during the acute phase, delayed phase, and overall for the comparison of treatment arms. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare the severity of nausea in each 24-h period in all patients by arm.

The proportion of patients without nausea in each phase and throughout the 120 h at 24-h intervals was compared by the chi-square test between the treatment arms and between subgroups stratified by sex, age, and type of chemotherapy. All statistical tests were two-tailed. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. SAS software version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of the 1143 patients randomized, 1119 patients were treated, 5 of whom were subsequently excluded from the efficacy analyses because of the insufficiently emetogenic chemotherapy. Thus, 1114 patients (n = 555 in the PALO arm; n = 559 in the GRA arm) were included in the modified ITT cohort for the efficacy analyses.

The baseline characteristics of the modified ITT cohort are shown in Table 1. The sex distribution was comparable between the two treatment arms (58.7 % [326/555 patients] in the PALO arm vs. 58.0 % [324/559] in the GRA arm were female), as was the age distribution (67.7 % [376/555] vs. 68.0 % [380/559] ≥55 years, respectively). Prior to study initiation, the majority of patients in two arms (>90 %) were chemotherapy naive. A similar proportion of patients in both study arms received cisplatin (56.9 % [316/555] vs. 57.8 % [323/559], respectively) or AC/EC (43.1 % [239/555] vs. 42.2 % [236/559], respectively).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the modified intention-to-treat cohort

| Palonosetron arm | Granisetron arm | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 555) | (n = 559) | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 326 (58.7) | 324 (58.0) |

| Male | 229 (41.3) | 235 (42.0) |

| Age, years | ||

| Mean (SD) | 58.4 (10.4) | 58.0 (10.5) |

| ≥55 years, n (%) | 376 (67.7) | 380 (68.0) |

| <55 years, n (%) | 179 (32.3) | 179 (32.0) |

| Tumor type, n (%) | ||

| Non-small cell lung cancer | 248 (44.7) | 249 (44.5) |

| Small cell lung cancer | 47 (8.5) | 52 (9.3) |

| Breast cancer | 239 (43.1) | 236 (42.2) |

| Others | 21 (3.8) | 22 (3.9) |

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | ||

| Cisplatin | 316 (56.9) | 323 (57.8) |

| AC/EC | 239 (43.1) | 236 (42.2) |

| Previous chemotherapy, n (%) | ||

| Naive | 519 (93.5) | 516 (92.3) |

| Non-naive | 36 (6.5) | 43 (7.7) |

AC/EC doxorubicin or epirubicin with cyclophosphamide, SD standard deviation

Nausea control

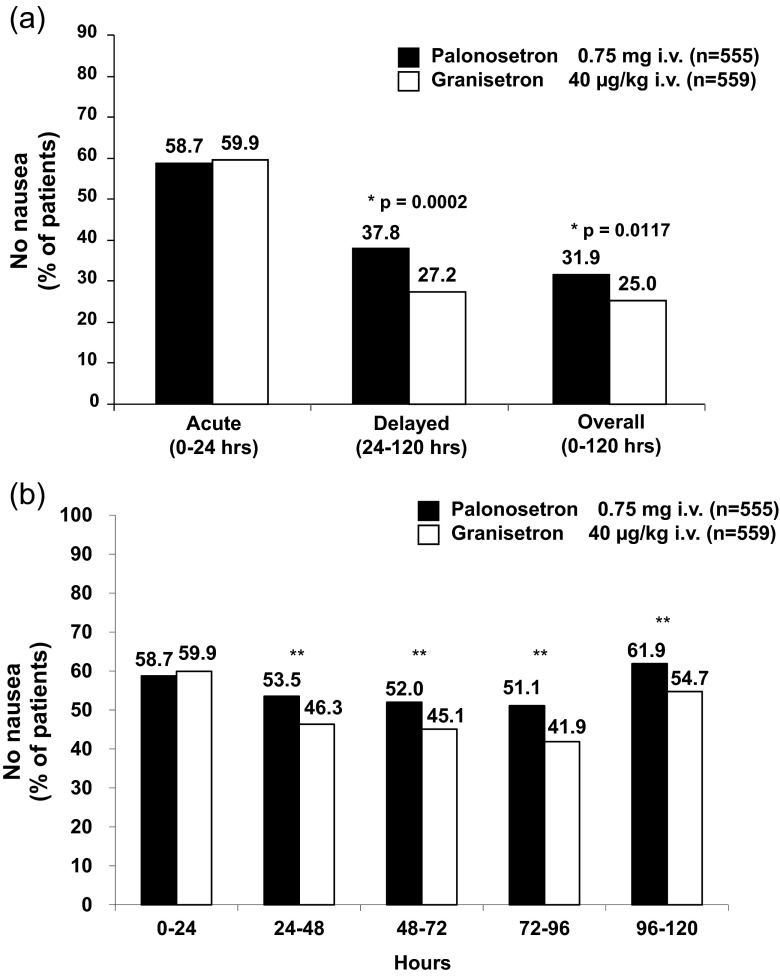

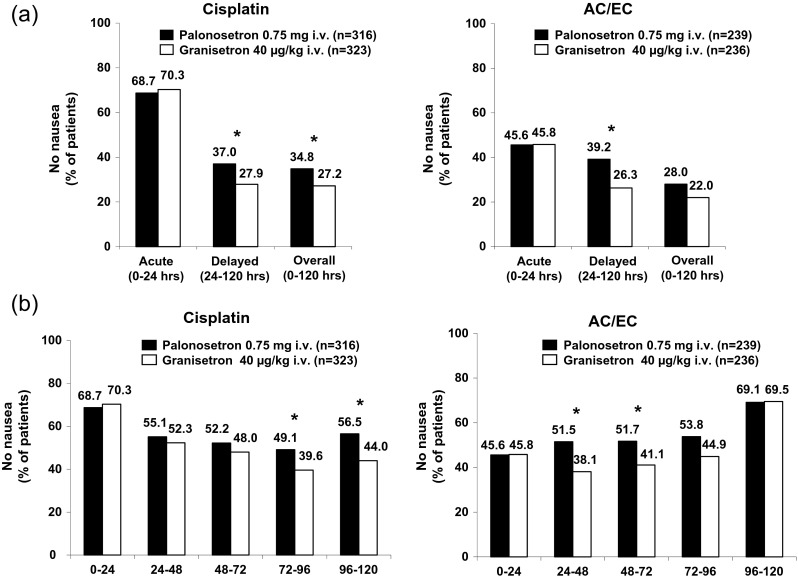

On day 1, in the acute phase, the proportion of patients without nausea was similar in the PALO arm (58.7 % [326/555]) and in the GRA arm (59.9 % [335/559]). However, there was a significantly higher proportion of patients without nausea in the delayed phase (p = 0.0002) and overall (p = 0.0117) in the PALO arm than in the GRA arm (Fig. 1a). When assessed daily, the proportion of patients without nausea was significantly higher in the PALO arm than in the GRA arm on days 2, 3, 4, and 5 (all p < 0.05) (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of patients without nausea (a) in each phase and (b) on each day for each treatment arm. *p values determined by Fisher’s exact test, **p < 0.05 (chi-square test)

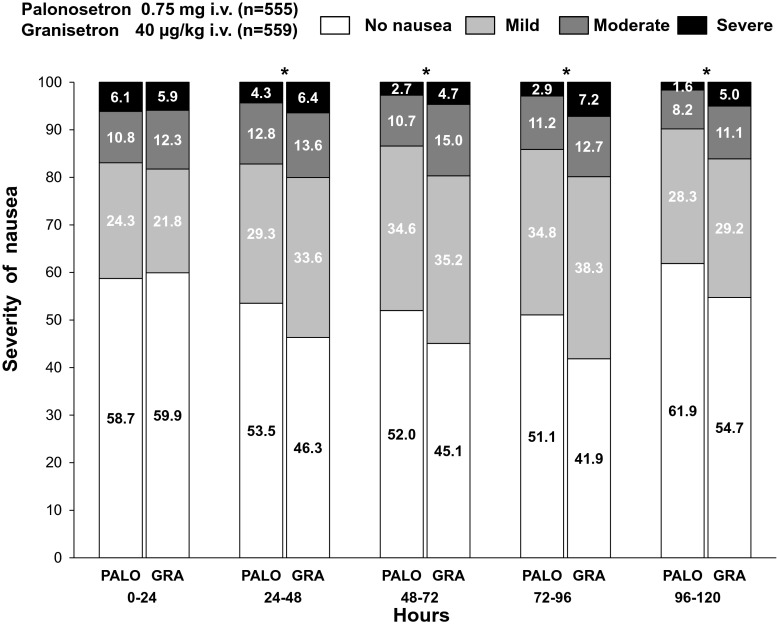

Severity of nausea over time was analyzed for both treatment arms (Fig. 2). The proportion of patients who experienced severe nausea was similar in two arms on day 1 (6.1 % [34/555] vs. 5.9 % [33/559]), but was lower in the PALO arm on day 2 (4.3 % [24/553] vs. 6.4 % [36/559]), day 3 (2.7 % [15/552] vs. 4.7 % [26/559]), day 4 (2.9 % [16/552] vs. 7.2 % [40/559]), and day 5 (1.6 % [9/551] vs. 5.0 % [28/559]). The severity of nausea was significantly lower in the PALO arm during the 24–48 h (p = 0.0180), 48–72 h (p = 0.0043), 72–96 h (p = 0.0005), and 96–120 h (p = 0.0030) periods than in the GRA arm.

Fig. 2.

Severity of nausea over time for both treatment arms. *p < 0.05 (Wilcoxon test). PALO, palonosetron; GRA, granisetron

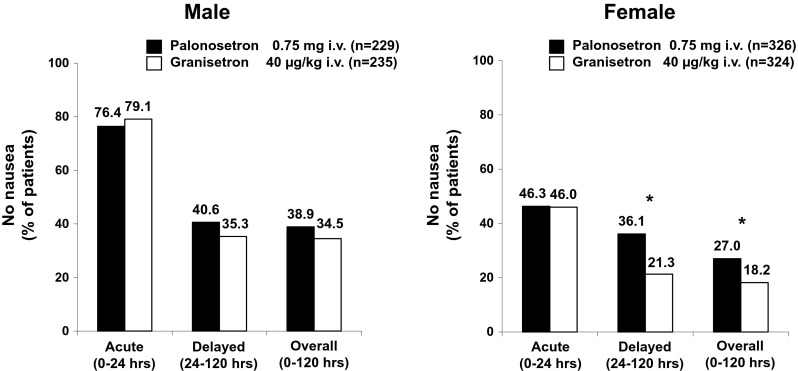

The proportion of patients without nausea was also assessed according to the stratification factors including sex, age, and chemotherapy regimen. In male patients, no significant difference was noted between two arms in any phase. In the acute phase, the proportion of patients without nausea was slightly lower in the PALO arm than in the GRA arm (76.4 % [175/229] vs. 79.1 % [186/235]), whereas it was slightly higher in the delayed phase (40.6 % [93/229] vs. 35.3 % [83/235]) and overall (38.9 % [89/229] vs. 34.5 % [81/235]) (Fig. 3). In female patients, No significant difference was noted between the treatment arms in the acute phase (46.3 % [151/326] vs. 46.0 % [149/324]), but a significant difference was noted in the delayed phase (36.1 % [117/324] vs. 21.3 % [69/324]) and overall (27.0 % [88/326] vs. 18.2 % [59/324]), with a higher proportion of patients without nausea in the PALO arm than in the GRA arm (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Proportion of patients stratified by sex without nausea in each phase. *p < 0.05 (chi-square test)

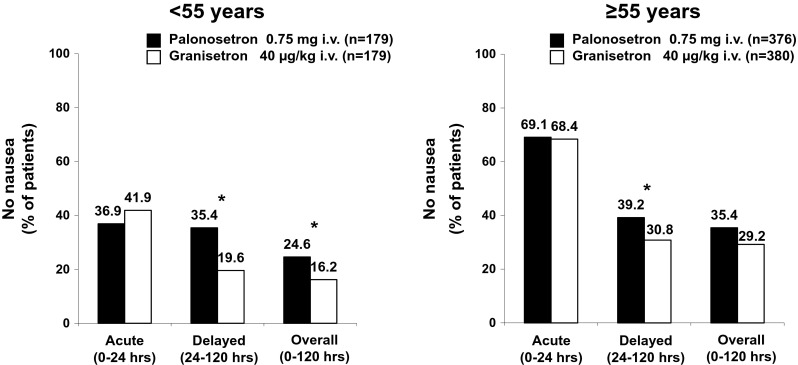

In the <55 and ≥55 years age groups, the proportion of patients without nausea was similar between the two treatment arms in the acute phase (≥55 years, 69.1 % [260/376] vs. 68.4 % [260/380]; <55 years, 36.9 % [66/179] vs. 41.9 % [75/179]) (Fig. 4). However, in both age groups, the proportion of patients without nausea was higher in the PALO arm than in the GRA arm in the delayed phase (≥55, 39.2 % [147/375] vs. 30.8 % [117/380]; <55, 35.4 %, [63/178] vs. 19.6 % [35/179]) and overall (35.4 % [133/376] vs. 29.2 % [111/380]; <55, 24.6 % [44/179] vs. 16.2 % [29/179]) (Fig. 4). The differences were significant in the delayed phase and overall in younger patients and in the delayed phase in older patients (all p < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Proportion of patients stratified by age without nausea in each phase. *p < 0.05 (chi-square test)

In the cisplatin and AC/EC chemotherapy groups, the proportion of patients without nausea was similar in the PALO and GRA arms in the acute phase (68.7 % [217/316] vs. 70.3 % [227/323] for cisplatin; 45.6 % [109/239] vs. 45.8 % [108/236] for AC/EC) (Fig. 5a). In the delayed phase and overall, the proportion of patients without nausea was higher in the PALO arm (37.0 % [117/316] and 34.8 % [110/316] for cisplatin; 39.2 % [93/237] and 28.0 % [67/239] for AC/EC) than in the GRA arm (27.9 % [90/323] and 27.2 % [88/323] for cisplatin; 26.3 % [62/236] and 22.0 % [52/236] for AC/EC) (Fig. 5a). The differences were significant in the delayed phase and overall in the cisplatin chemotherapy group and in the delayed phase in the AC/EC chemotherapy group (all p < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Proportion of patients stratified by chemotherapy treatment without nausea a in each phase and b in each 24-h interval. *p < 0.05 (chi-square test). Cisplatin or doxorubicin/epirubicin plus cyclophosphamide(AC/EC)

In patients stratified by chemotherapy, the proportion of patients without nausea was also analyzed daily (Fig. 5b). In the cisplatin-treated group, the proportion of patients without nausea was similar for both PALO and GRA arms on days 1, 2, and 3 (68.7 % [217/316], 55.1 % [174/316], 52.2 % [165/316] vs. 70.3 % [227/323], 52.3 % [169/323], 48.0 % [155/323]), but was significantly higher in the PALO arm on day 4 (49.1 % [155/316] vs. 39.6 % [128/323]; p < 0.05) and day 5 (56.5 % [178/315] vs. 44.0 % [142/323]; p < 0.05). In the AC/EC-treated group, the proportion of patients without nausea was similar with PALO and GRA treatments on day 1 (45.6 % [109/239] vs. 45.8 % [108/236]) and day 5 (69.1 % [163/236] vs. 69.5 % [164/236]), but was higher with PALO treatment on days 2, 3, and 4 (51.5 % [122/237], 51.7 % [122/236], 53.8 % [127/236] vs. 38.1 % [90/236], 41.1 % [97/236], 44.9 % [106/236]). This difference was significant on days 2 and 3 (both p < 0.05) (Fig. 5b).

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of Saito et al.’s phase 3 study in Japanese patients receiving HEC [22], PALO achieved significantly better control of nausea than GRA in the overall study population during the delayed phase, overall, and during each day of the delayed phase. When evaluated by subgroups for age, sex, and type of chemotherapy, the proportion of “nausea-free” patients in the delayed phase was higher with PALO treatment than with GRA treatment, and the difference was significant in female patients, both age groups, and both chemotherapy groups. It is of particular interest that PALO protects against nausea in the delayed phase in female patients and in both age groups because a recent pooled analysis of two phase 2 trials and one phase 3 trial of PALO showed that younger age (<55 years) is a risk factor for acute CINV and that female sex is a risk factor for both acute and delayed CINV [24].

Treatment outcome and survival are reported to be associated with the relative dose intensity of chemotherapy [33, 34]. Therefore, when administering chemotherapy, it is also necessary to give appropriate supportive care treatment to achieve maximal benefit, with consideration of the related side effects. The most dreaded adverse effects of chemotherapy that have long been recognized are nausea and vomiting [35]. In a recent multicenter, prospective, observational study in Japan, it was reported that nausea and vomiting during the acute phase were relatively well controlled but the incidence of nausea during the delayed phase was high in the patients receiving HEC and MEC. Such adverse events lead to loss of appetite, which is related to poor treatment outcomes and short survival [36]. Also, this study reported that female sex and age were risk factors for acute and delayed nausea. Cancer patients tend to report symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting, earlier and more frequently than clinicians. In addition, patients’ reports were found to have a higher concordance than clinicians’ reports with overall health status [37, 38]. The incidence of CINV may also be considerably underestimated by healthcare providers, particularly in the delayed phase [39]. The incidence of delayed CINV was underestimated by 75 % of physicians and nurses after the treatment of HEC and MEC. Delayed nausea in particular was underestimated by 21 percentage points after HEC and 28 percentage points after MEC [37]. Delayed nausea and vomiting are still important targets in the development of improved antiemetics. Effective treatments are needed especially for nausea, as this adverse event reduces cancer patients’ quality of life considerably [1]. However, in spite of advanced understanding of the physiology of CINV, the ability to treat nausea remains poor as its neurochemistry seems much more complex [30].

A recent trial reported that PALO was as effective as GRA in the prophylaxis of delayed nausea [40]. However, comparison between their study and ours is complex due to differences in experimental setup and data reporting [41]. The findings from our study are consistent with those from several phase 3 clinical trials showing that PALO has superior efficacy in nausea control in comparison with first-generation 5-HT3 RAs [18–20, 42]. In the MEC setting, it has been reported that the proportion of patients who experience no nausea was significantly greater in those receiving PALO than in those receiving dolasetron on days 2 and 3 of treatment [18]. Accordingly, another phase 3 study showed better control of nausea with PALO than with ondansetron on days 3, 4, and 5 of treatment [19]. In the HEC setting, Aapro et al. also reported higher protection from acute nausea in patients treated with PALO than in those treated with ondansetron, although differences between the treatment arms did not reach statistical significance [20].

A recent meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials showed that, in general, PALO was statistically superior to first-generation 5-HT3 RAs in terms of complete response, complete control, without emesis, and without nausea. Particularly, in both the delayed phase and overall in the studies including corticosteroid, the proportion of patients who experience no nausea was significantly higher in those receiving PALO compared with those receiving first-generation 5-HT3 RAs [43]. Taken together, the great majority of studies suggested better nausea control outcomes with PALO during the delayed phase than with first-generation 5-HT3 RAs. Furthermore, Aogi et al. reported that PALO plus dexamethasone was effective for the control of nausea in multiple cycles of HEC [44].

In conclusion, in this study, PALO was found to be more effective than GRA in prophylaxis of nausea induced by HEC, both in the delayed phase and overall. Subgroup analysis showed that PALO was more effective than GRA in young patients and female patients, who are at high risk of CINV, both in the delayed phase and overall.

Acknowledgments

The trial was funded by Taiho Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan. Editorial and medical writing assistance was provided by Anna Hooijkaas, PhD, TRM Oncology, the Hague, the Netherlands, and funded by Helsinn Healthcare SA, Lugano, Switzerland. Taiho Pharmaceutical provided a full review of the article.

Compliance with ethical standards

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each study site before imitation of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before enrollment.

Conflicts of interest

KK has received remuneration from Taiho Pharmaceutical and Chugai Pharmaceutical and funding from Taiho Pharmaceutical. MS has received remuneration from Taiho Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, and Helsinn Healthcare SA. KA has received remuneration from Taiho Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Eizai, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Sanofi, Daiichi Sankyo Company, Nihon Medi-Physics, and Becton Dickinson and Company. IS has received remuneration from Taiho Pharmaceutical and Chugai Pharmaceutical. HY has received remuneration and funding from Taiho Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, and Ono Pharmaceutical. YY has received remuneration from Taiho Pharmaceutical and Chugai Pharmaceutical. HS has received remuneration and funding from Taiho Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Eli Lily, and Ono Pharmaceutical and funding from MSD and Bristol-Myers Squibb. KI has received remuneration and funding from Taiho Pharmaceutical and funding from Novartis, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo Company, Puma Biotechnology, and Nippon Kayaku. CK and TO have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Bloechl-Daum B, Deuson RR, Mavros P, Hansen M, Herrstedt J. Delayed nausea and vomiting continue to reduce patients’ quality of life after highly and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy despite antiemetic treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(27):4472–4478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilarius DL, Kloeg PH, van der Wall E, van den Heuvel JJ, Gundy CM, Aaronson NK. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in daily clinical practice: a community hospital-based study. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(1):107–117. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1073-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hesketh PJ. Comparative review of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in the treatment of acute chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer Invest. 2000;18(2):163–173. doi: 10.3109/07357900009038248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rojas C, Slusher BS. Pharmacological mechanisms of 5-HT(3) and tachykinin NK(1) receptor antagonism to prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;684(1-3):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dando TM, Perry CM. Aprepitant: a review of its use in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Drugs. 2004;64(7):777–794. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464070-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy GK, Gralla RJ, Hesketh PJ. Novel neurokinin-1 antagonists as antiemetics for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced emesis. Support Cancer Ther. 2006;3(3):140–142. doi: 10.3816/SCT.2006.n.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wickham R. Evolving treatment paradigms for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer Control. 2012;19(2 Suppl):3–9. doi: 10.1177/107327481201902s02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feyer P, Jordan K. Update and new trends in antiemetic therapy: the continuing need for novel therapies. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(1):30–38. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basch E, Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Prestrud AA, Temin S, Lyman GH. Antiemetics: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(6):395–398. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Antiemesis. Version 1.2015. (2015) National Comprehensive Cancer Network. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. Accessed 1 Apr 2015

- 11.Roila F, Herrstedt J, Aapro M, Gralla RJ, Einhorn LH, Ballatori E, Bria E, Clark-Snow RA, Espersen BT, Feyer P, Grunberg SM, Hesketh PJ, Jordan K, Kris MG, Maranzano E, Molassiotis A, Morrow G, Olver I, Rapoport BL, Rittenberg C, Saito M, Tonato M, Warr D. Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v232–v243. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roila F, Herrstedt J, Gralla RJ, Tonato M. Prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: guideline update and results of the Perugia consensus conference. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(Suppl 1):S63–S65. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wickham R. Best practice management of CINV in oncology patients: II. Antiemetic guidelines and rationale for use. J Support Oncol. 2010;8(2 Suppl 1):10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aapro M, Molassiotis A, Dicato M, Pelaez I, Rodriguez-Lescure A, Pastorelli D, Ma L, Burke T, Gu A, Gascon P, Roila F. The effect of guideline-consistent antiemetic therapy on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): the Pan European Emesis Registry (PEER) Ann Oncol. 2012;23(8):1986–1992. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geling O, Eichler HG. Should 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonists be administered beyond 24 hours after chemotherapy to prevent delayed emesis? Systematic re-evaluation of clinical evidence and drug cost implications. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(6):1289–1294. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hesketh PJ, Van Belle S, Aapro M, Tattersall FD, Naylor RJ, Hargreaves R, Carides AD, Evans JK, Horgan KJ. Differential involvement of neurotransmitters through the time course of cisplatin-induced emesis as revealed by therapy with specific receptor antagonists. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(8):1074–1080. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00674-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Likun Z, Xiang J, Yi B, Xin D, Tao ZL. A systematic review and meta-analysis of intravenous palonosetron in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in adults. Oncologist. 2011;16(2):207–216. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenberg P, Figueroa-Vadillo J, Zamora R, Charu V, Hajdenberg J, Cartmell A, Macciocchi A, Grunberg S. Improved prevention of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting with palonosetron, a pharmacologically novel 5-HT3 receptor antagonist: results of a phase III, single-dose trial versus dolasetron. Cancer. 2003;98(11):2473–2482. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gralla R, Lichinitser M, Van Der Vegt S, Sleeboom H, Mezger J, Peschel C, Tonini G, Labianca R, Macciocchi A, Aapro M. Palonosetron improves prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: results of a double-blind randomized phase III trial comparing single doses of palonosetron with ondansetron. Ann Oncol. 2003;14(10):1570–1577. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aapro MS, Grunberg SM, Manikhas GM, Olivares G, Suarez T, Tjulandin SA, Bertoli LF, Yunus F, Morrica B, Lordick F, Macciocchi A. A phase III, double-blind, randomized trial of palonosetron compared with ondansetron in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(9):1441–1449. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin SJ, Hatoum HT, Buchner D, Cox D, Balu S. Impact of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:215. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito M, Aogi K, Sekine I, Yoshizawa H, Yanagita Y, Sakai H, Inoue K, Kitagawa C, Ogura T, Mitsuhashi S. Palonosetron plus dexamethasone versus granisetron plus dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, comparative phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(2):115–124. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doherty KM. Closing the gap in prophylactic antiemetic therapy: patient factors in calculating the emetogenic potential of chemotherapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 1999;3(3):113–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sekine I, Segawa Y, Kubota K, Saeki T. Risk factors of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: index for personalized antiemetic prophylaxis. Cancer Sci. 2013;104(6):711–717. doi: 10.1111/cas.12146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massa E, Astara G, Madeddu C, Dessi M, Loi C, Lepori S, Mantovani G. Palonosetron plus dexamethasone effectively prevents acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy in pre-treated patients who have failed to respond to a previous antiemetic treatment: comparison between elderly and non-elderly patient response. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;70(1):83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruff P, Paska W, Goedhals L, Pouillart P, Riviere A, Vorobiof D, Bloch B, Jones A, Martin C, Brunet R, et al. Ondansetron compared with granisetron in the prophylaxis of cisplatin-induced acute emesis: a multicentre double-blind, randomised, parallel-group study. The Ondansetron and Granisetron Emesis Study Group. Oncology. 1994;51(1):113–118. doi: 10.1159/000227321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Italian Group of Antiemetic Research Ondansetron versus granisetron, both combined with dexamethasone, in the prevention of cisplatin-induced emesis. Ann Oncol. 1995;6(8):805–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pradermdee P, Manusirivithaya S, Tangjitgamol S, Thavaramara T, Sukwattana P. Antiemetic effect of ondansetron and dexamethasone in gynecologic malignant patients receiving chemotherapy. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89(Suppl 4):S29–S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleisbauer JP, Garcia-Giron C, Antimi M, Azevedo MC, Balmes H, Massuti-Sureda B, Contu A, Luque A, Pellier P. Granisetron plus methylprednisolone for the control of high-dose cisplatin-induced emesis. Anticancer Drugs. 1998;9(5):387–392. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199806000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanger GJ, Andrews PL. Treatment of nausea and vomiting: gaps in our knowledge. Auton Neurosci. 2006;129(1-2):3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warr DG, Hesketh PJ, Gralla RJ, Muss HB, Herrstedt J, Eisenberg PD, Raftopoulos H, Grunberg SM, Gabriel M, Rodgers A, Bohidar N, Klinger G, Hustad CM, Horgan KJ, Skobieranda F. Efficacy and tolerability of aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with breast cancer after moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(12):2822–2830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeo W, Mo FK, Suen JJ, Ho WM, Chan SL, Lau W, Koh J, Yeung WK, Kwan WH, Lee KK, Mok TS, Poon AN, Lam KC, Hui EK, Zee B. A randomized study of aprepitant, ondansetron and dexamethasone for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in Chinese breast cancer patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113(3):529–535. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9957-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonadonna G, Valagussa P, Moliterni A, Zambetti M, Brambilla C. Adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil in node-positive breast cancer: the results of 20 years of follow-up. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(14):901–906. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504063321401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Epelbaum R, Faraggi D, Ben-Arie Y, Ben-Shahar M, Haim N, Ron Y, Robinson E, Cohen Y. Survival of diffuse large cell lymphoma. A multivariate analysis including dose intensity variables. Cancer. 1990;66(6):1124–1129. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900915)66:6<1124::AID-CNCR2820660608>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun CC, Bodurka DC, Weaver CB, Rasu R, Wolf JK, Bevers MW, Smith JA, Wharton JT, Rubenstein EB. Rankings and symptom assessments of side effects from chemotherapy: insights from experienced patients with ovarian cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(4):219–227. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0710-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamura K, Aiba K, Saeki T, Nakanishi Y, Kamura T, Baba H, Yoshida K, Yamamoto N, Kitagawa Y, Maehara Y, Shimokawa M, Hirata K, Kitajima M (2015) Testing the effectiveness of antiemetic guidelines: results of a prospective registry by the CINV Study Group of Japan. Int J Clin Oncol. doi:10.1007/s10147-015-0786-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Grunberg SM, Deuson RR, Mavros P, Geling O, Hansen M, Cruciani G, Daniele B, De Pouvourville G, Rubenstein EB, Daugaard G. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis after modern antiemetics. Cancer. 2004;100(10):2261–2268. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(10):865–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grunberg S. Patient-centered management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer Control. 2012;19(2 Suppl):10–15. doi: 10.1177/107327481201902s03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roscoe JA, Heckler CE, Morrow GR, Mohile SG, Dakhil SR, Wade JL, Kuebler JP. Prevention of delayed nausea: a University of Rochester Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program study of patients receiving chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(27):3389–3395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Celio L, Aapro M. Research on chemotherapy-induced nausea: back to the past for an unmet need? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(10):1376–1377. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Navari RM. Palonosetron for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with cancer. Future Oncol. 2010;6(7):1073–1084. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Popovic M, Warr DG, Deangelis C, Tsao M, Chan KK, Poon M, Yip C, Pulenzas N, Lam H, Zhang L, Chow E. Efficacy and safety of palonosetron for the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(6):1685–1697. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aogi K, Sakai H, Yoshizawa H, Masuda N, Katakami N, Yanagita Y, Inoue K, Kuranami M, Mizutani M, Masuda N. A phase III open-label study to assess safety and efficacy of palonosetron for preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in repeated cycles of emetogenic chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(7):1507–1514. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]