Abstract

Systemic fibrosis from gadolinium-based magnetic resonance imaging contrast is a scourge for the afflicted. Although gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis is a rare condition, the threat of litigation has vastly altered clinical practice. Most theories concerning the etiology of the fibrosis are grounded in case reports rather than experiment. This has led to the widely accepted conjecture that the relative affinity of certain contrast agents for the gadolinium ion inversely correlates with the risk of succumbing to the disease. How gadolinium-containing contrast agents trigger widespread and site-specific systemic fibrosis and how chronicity is maintained are largely unknown. This review highlights experimentally-derived information from our laboratory and others that pertain to our understanding of the pathophysiology of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis.

Keywords: fibrosis, gadolinium, nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy, NADPH oxidase, skin diseases

patients with chronic kidney disease, including end-stage renal disease, tend to be burdened with cutaneous afflictions that are still not well understood (34). Among these, gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis is an underrecognized disorder (93) and in a class separate from other described fibrosing disorders (30).

Gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis was originally termed “nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy” and then changed to “nephrogenic systemic fibrosis” after the suspicion that more than just the skin was involved. However, the term “nephrogenic” is a misnomer (54); renal insufficiency is requisite, but this alone does not cause the disease: it is caused by gadolinium-based magnetic resonance imaging contrast (42). Therefore, gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis has been proposed as an alternative, and more accurate, term (54).

Obviously, gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis is iatrogenic: it joins a number of cutaneous fibrosing disorders that have been drug or environmentally induced. Such agents include toxic/denatured rapeseed oil, tainted l-tryptophan supplements (the eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome), polyvinyl chloride, bleomycin, and carbidopa (10).

There is a registry for reporting cases, the International Center for Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis Research (http://www.icnfdr.org) (19). Since this was last updated on June 15, 2013 (at the time of this writing), no cases of gadolinium-associated fibrosis have been recorded.

Clearance of Gadolinium-Based Contrast

“The composition of the blood is determined not by what the mouth ingests but by what the kidneys keep” (91). One can estimate the plasma concentration (C) of a drug by using the equation,

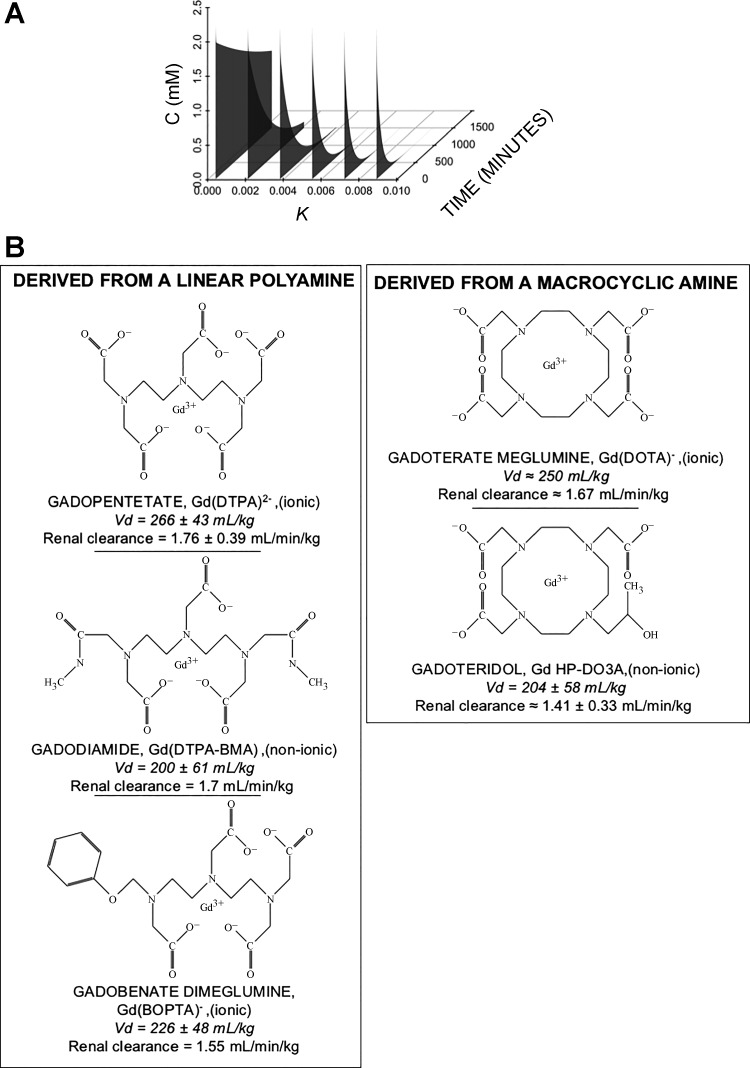

where C0 is the initial plasma concentration (once distributed in the vascular compartment), k is a rate constant, and t is time. (The volumes of distribution for magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents are almost entirely the extracellular compartment; therefore, the distributive phase is negligible.) With substances that are eliminated by the kidney, renal insufficiency attenuates the rate constant k (Fig. 1A). Most contrast (whether it is iodinated or gadolinium-based) is cleared by the kidney. Gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis is not found in patients with normal renal function; therefore, prolonged retention of the contrast seemed to be a reasonable hypothesis regarding the initiation of the disease.

Fig. 1.

Gadolinium-based contrast: renal clearance and their chemical structures. A: clearance of intravascular contrast. Most contrast agents, whether iodinated or gadolinium based, are eliminated by renal excretion. The concentration of the substance (C) can be determined by a clearance equation. The United States Food and Drug Administration-approved dose of most gadolinium-based contrast is 0.1 mmol/kg. After distribution, with a volume of distribution that is almost entirely the extracellular space, the rapidity of elimination of contrast is determined by renal function. Curves were created based on the reported half-life for magnetic resonance contrast (i.e., the far-right curve) and reducing the rate constant, k, by 20% (modeling the elimination with worsening renal function). B: the various chemical structures of commonly used gadolinium ligands. In general, these can be grouped as being somewhat “linear” or macrocyclic. Note that the number of carboxylic acid side chains determines whether the chelate has a neutral charge (“nonionic”) or not (“ionic”) (3). Vd, volume of distribution.

Types of Gadolinium-Based Contrast

An odds ratio provides a quantification of an association between a risk factor and contracting a disease. For gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis (GASF), this can be derived by examining the numbers of patients with and without the disease relative to whether they have been exposed to contrast or not,

| (1) |

The odds ratio for patients with end-stage renal disease contracting systemic fibrosis after an exposure to gadolinium-based contrast ranges from 20.6 to 41.3 (Table 1) (12, 17, 25, 79).

Table 1.

Cases and controls used for odds ratio calculations (with references)

| Study | Affected | Unaffected | Ref. No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Othersen et al. | 79 | ||

| Contrast exposure | 4 | 257 | |

| No contrast exposure | 0 | 588 | |

| Never | 0 | 588 | |

| One exposure | 2 | 191 | |

| Multiple exposures | 2 | 70 | |

| Collidge et al. | 17 | ||

| Contrast exposure | 13 | 395 | |

| No contrast exposure | 1 | 1,403 | |

| Deo et al. | 25 | ||

| Contrast exposure | 3 | 84 | |

| No contrast exposure | 0 | 380 | |

| One exposure | 2 | 60 | |

| Multiple exposures | 1 | 24 | |

| Broome et al. | 12 | ||

| Contrast exposure | 12 | 301 | |

| No contrast exposure | 0 | 258 |

Nos. are no. of patients. Othersen, Maize, Woolson, and Budisavljevic (79) sought gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis cases in 849 chronic dialysis patients over 5 yr at the Medical University of South Carolina. Among 261 exposed to gadolinium, 4 patients developed the disease. Collidge, Thomson, Mark, Traynor, Jardine, Morris, Simpson, and Roditi (17) conducted a retrospective study involving chronic dialysis patients at two units west of Scotland from January 1, 2000 to July 1, 2006. In three hemodialysis facilities and one peritoneal dialysis unit surrounding Bridgeport, Connecticut, three cases of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis were identified in an 18-mo window (25). Broome, Girguis, Baron, Cottrell, Kjellin and Kirk (12) conducted a retrospective study. There were 12 cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, 8 of whom were on chronic dialysis and 4 with hepato-renal syndrome.

Six million doses of magnetic resonance imaging contrast are administered annually (47). Gadolinium is a marker of anthropomorphic pollution, having been detected downstream of many cities harboring magnetic resonance imagers (8, 64). It is a transition metal of the lanthanide series with paramagnetic properties, making it ideal for magnetic resonance imaging (66). Gadolinium, such as that delivered in the form of GdCl3, is toxic; therefore, gadolinium-based contrast is composed of a variety of organic ligands that avidly bind the metal, greatly reducing its harm. Before 2006, the safety of gadolinium-based contrast was unparalleled. Patients with kidney disease would routinely undergo contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging or arteriography to avoid the (suspected) nephrotoxicity of iodine-based contrast. Now we know that those with renal insufficiency and an exposure to gadolinium-based contrast are exclusively at risk. Furthermore, a new disorder, “gadolinium deposition disease,” has been proposed within the last year: patients who are exposed to repeated contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance scans demonstrate brain deposition of the metal (74).

With gadolinium being so noxious, there are a variety of amine-containing organic ligands with different properties that have been manufactured to tightly couple with the metal, greatly reducing its toxicity (Fig. 1B). Some of these organic molecules are (roughly) linear, and others are (relatively) large rings, i.e., “macrocyclic.” When the number of acidic residues (typically as side chains) on a ligand is 3, i.e., equal to the valence of Gd3+, the formulation is regarded as “nonionic”; otherwise it is “ionic.” For these ligands, the affinities for the gadolinium cation in an equilibrium reaction strongly favors the ligand-bound form,

| (2) |

The measurements of the ligand-gadolinium affinities are expressed in terms of “thermodynamic stabilities,” Ktherm (26):

| (3) |

These thermodynamic stabilities are among several in vitro measurements that describe the propensity of the ligands to retain gadolinium. At a physiological pH, though, the amines of the ligands will be partially protonated:

| (4) |

The conditional stability constant, Keff, accounts for this protonation,

| (5) |

This implies that the degree of acidity in vivo will reduce the binding of the ligand to gadolinium (influencing the reaction in Eq. 3 to tend left). Therefore, the behaviors of the gadolinium-ligand complexes in vivo may not be predictable based on the simple, single values of their thermodynamic stabilities (88).

From 1997 to 2006, a commonly used gadolinium-based contrast agent was Omniscan, which is largely gadodiamide {gadolinium 5,8-bis(carboxymethyl)-11-[2-(methylamino)-2-oxoethyl]-3-oxo-2,5,8,11-tetraazatridecan-13-oic acid, Gd(DTPA-BMA)}. [Note that there is an excess of calcium-bound ligand, caldiamide, in the brand Omniscan. The purpose of this additional chelate is to provide an excess amount of ligand (81); given the relatively low conditional stability constant of DTPA-BMA, excess nongadolinium-bound ligand favors the movement of the reactions depicted in Eqs. 2 and 4 to the right (88).] Gadodiamide has been tied to a large number of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis cases, and it has a relatively low conditional stability constant compared with the other contrast agents. This led to the speculation that the release of gadolinium from the chelate is an initial step in triggering fibrosis (85).

The displacement of gadolinium from a ligand by another metal, such as zinc, is termed “transmetallation” (83), i.e., the expulsion of the paramagnetic ion by an endogenous ion. In terms of pathogenesis, transmetallation is more likely to occur with linear ligands than with macrocyclic ones, where the gadolinium ion is “caged.” Body cations (calcium, zinc, or iron, for instance) may alter the thermodynamic equilibrium with gadolinium and a ligand, promoting the liberation of the lanthanide ion (47). Once liberated from the chelate, it has been speculated that Gd3+ is prone to form low-solubility compounds, such as Gd(OH)3 or Gd(PO4)3 with subsequent pathological effects (23, 70). In fact, both the European Medicines Agency and the American College of Radiology have categorized the various ligands into different safety classes (Table 2) despite being grounded in purely observational data. Despite this, a class effect of gadolinium-based contrast agents has been assumed by the United States Federal Drug Administration (2, 53).

Table 2.

Categorization of magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents according to the American College of Radiology and the European Medicines Agency

| American College of Radiology Group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| European Medicines Agency | I | II | III |

| High | Gadodiamide | ||

| High | Gadopentetate | ||

| High | Gadoversetamide | ||

| Medium | Gadobenate dimeglumine | Gadofosveset | |

| Medium | Gadoxetic acid | ||

| Low | Gadobutrol | ||

| Low | Gadoteric acid | ||

| Low | Gadoteridol | ||

Whether transmetallation occurs in vivo and is an initial step in triggering the disease is controversial (88, 98). In vivo, the candidate metals, such as zinc or copper, are an order less in concentration than the peak dose of gadolinium-bound ligand, and these physiological elements are often protein-bound, thereby reducing the free, ionized forms that could participate in such a reaction (96). Nonetheless, regardless of the conditional stability constants, all gadolinium-based contrast agents lead to residual metal deposition in several different organs (97). (Radiolabeled gadolinium in different formulations has been studied in both mice and rats. The formulations tested included gadodiamide, gadopentetate, gadoterate meglumine, and gadoteridol. Fourteen days after administration, the isotope was detectable in several organs, regardless of the ligand structure.) A meta-analysis has supported the United States Food and Drug Administration's original supposition of a class effect, and all gadolinium-based contrast agents are assumed to carry some risk of precipitating the disease (2). The pathological effects of gadolinium, such a commonly used substance in contemporary clinical medicine, have been largely unexplored.

Contrast Dose

The United States Food and Drug Administration-approved dose of most gadolinium-based contrast, such as gadodiamide, for an adult undergoing an imaging procedure is 0.1 mmol/kg. Commonly used doses range from 0.2 up to 0.9 mmol/kg, with larger amounts often employed in magnetic resonance angiography (95). Among 116 patients with creatinine ranging from 1.6 to 9.5 mg/dl, all of them with creatinine clearances ≤15 ml/min, who underwent abdominal magnetic resonance angiographies with single doses of gadolinium-based contrast, none developed systemic fibrosis within a year (78). That being said, the original papers linking contrast to systemic fibrosis did not indicate dose dependence (70). In an analysis from four different centers, the cumulative lifetime exposures in afflicted patients ranged from the label dose of 0.1 mmol/kg up to 0.95 mmol/kg (103). Therefore, the evidence that the risk of systemic fibrosis relates to the dose of gadolinium-based contrast is weak (1). The caveat to pinning dose dependence, like many other purported risk factors, to gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis, is that it is a very rare condition: outside of gadolinium exposure and renal insufficiency, other hazards will be difficult to accurately assess and quantify. The odds ratios for end-stage renal disease patients to develop systemic fibrosis after single, label doses of gadodiamide may range from 22 (12) to 32.5 (70). Curiously, the onset to the disease after exposure varies immensely, ranging from 24 h to several years (43, 70, 71, 73).

Since a variety of contrast formulations have been linked to this ailment, gadolinium is theorized to be a causative factor. As mentioned, the type of ligand may be a factor (15, 25, 62, 70), but there are little prospective or experimental data to support this contention. More cases have been reported with “linear” and “nonionic” agents (Omniscan: gadodiamide; OptiMark: gadoversetamide) (52) than for cyclic and “ionic” formulations (ProHance: gadoteridol; Gadovist: gadobutrol) (85). However, mountains of narrative reviews have gilded the “high thermodynamic stability” (often cyclic) ligands.

Some have proposed that gadolinium deposition in the involved organ, such as the skin, is the trigger for the disease, and this contention is supported by the finding of gadolinium in fibrotic lesions (28). It is postulated that pinocytosis of the contrast leads to a low-pH lysosomal environment, greater protonation of the ligand, and this promotes liberation of the gadolinium cation as an initial step in triggering fibrosis. This is how a ligand's “thermodynamic stability” may relate to the propensity to induce systemic fibrosis. Of note, under semiphysiological conditions (human serum, 37°C, in vitro), the percentage of gadolinium released from ligands varied from nearly 0% for gadopentetate to 20–35% for gadodiamide (31). [Frenzel and colleagues (31) measured the liberation of gadolinium ion from a number of different ligands in vitro, incubating the substances in human serum at 37°C. Despite demonstrating that gadoversetamide having the greatest propensity to release gadolinium, ranging from 30 to 45% after 15 days of incubation, and Magnevist among the agents with the least release (2% over the same time period), Magnevist has been associated with several cases of systemic fibrosis.] Despite these differences, a mechanism to explain why certain formulations seem to carry less risk than others, gadopentetate is still the second most common formulation tied to systemic fibrosis (80, 85). This suggests that very minute quantities of gadolinium meet the threshold to trigger the disorder, or the mechanism and degree of gadolinium release in the body are different than the in vitro setup.

Gadolinium from contrast-treated animals accumulates primarily in the liver. Gadodiamide-treated mice (with intact renal function) demonstrated residual 153Gd 14 days after exposure (97). Contrary to all in vivo publications using gadolinium-based contrast and our own experience with gadodiamide, GdCl3 has a profound effect on liver histology (92). Furthermore, in mice with renal insufficiency, the biodistribution of gadolinium deposition is altered in a manner where the liver is by far the largest reservoir organ, especially with respect to the skin (99). John Haylor et al. (44) (Academic Nephrology Unit, Medical School, Scheffield, UK) found that when rats with an 80% nephrectomy were given a single dose of gadodiamide (2.5 mmol/kg), the accumulation of gadolinium in the skin was remarkably low. Of particular interest is the relative accumulation of gadolinium in the liver with respect to the skin (44). Tissues obtained from autopsy analyzed with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy had detectable gadolinium in the skin, liver, lungs, intestinal wall, kidney, and skeletal muscle. The liver was noted to have chronic venous stasis, but not fibrosis (87).

Perhaps it is not the dose of gadolinium-based contrast, but the cumulative lifetime exposure that increases the risk or severity of systemic fibrosis (17). After all, one retrospective study found the odds ratio for systemic fibrosis in hemodialysis patients was 6.7, but this increased to 44.5 after having multiple exposures (79).

Gadolinium exposure and renal insufficiency cannot be the sole and rigid effectors of systemic fibrosis; many patients with end-stage renal disease on chronic dialysis do not acquire the disease, despite several exposures to gadolinium-based contrast (72).

It should be mentioned that there are a few cases that resemble gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis, but no history of contrast exposure could be found. A 19-yr-old underwent a noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging scan before a heart transplant, yet he developed symptoms 3 mo later. In another, a 22-yr-old woman received a cadaveric renal transplant after 5 yr of chronic hemodialysis. Within 6 wk, she had signs of systemic fibrosis, which was congruent with her skin biopsy. There was no evidence of exposure to either magnetic resonance imaging or gadolinium exposure (102). Another woman, 34 yr of age, underwent a transplant in her mid-20s. After this allograft failed, she began hemodialysis. Despite not having a history of magnetic resonance imaging contrast exposure, she developed fibrotic symptoms with a biopsy consistent with the disease (4). A man in his 50s underwent a kidney transplant in 1999 for end-stage renal disease. Shortly after the transplant, he developed spontaneous hyperpigmented plaques and firm nodules on his trunk and extremities. He did not have a history of gadolinium exposure, and the only magnetic resonance imaging scan was 5–6 yr after the transplant and onset of symptoms. Skin biopsy showed wall-to-wall fibroblast-like cells with disorganized collagen (11). Whether the donors of these organs had undergone gadolinium-enhanced radiological procedures was not reported. (Therefore, we entertain the possibility that systemic fibrosis can be transferred by a transplanted solid organ.)

Incidence and Prevalence

Ten percent of patients with gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis have never been dialyzed (86). In a retrospective study of patients referred to an academic nephrology group, 18% had been diagnosed with the disorder (69). Men and women appear to be equally susceptible, with an age range from 8 to 87 yr old (98).

Diagnosis

Some of the differential diagnoses for gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis are provided in Table 3. The typical scenario occurs in patients with impaired renal function (acute or chronic) after exposure to gadolinium contrast. [However, gadolinium exposure is not requisite for the diagnosis; the full criteria are listed in Girardi et al. (35).] Gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis resembles scleroderma, yet specific anatomic locations are involved (16). Patients present with lower extremity pain, paresthesias, or pruritus. Findings include edema, hyperpigmentation, papules, subcutaneous nodules, peau d'orange texturing, or hardened or tethered skin. Joints may have contractures with a concomitant compromise in the range of motion. The fibrosis of skeletal muscle and a number of visceral organs have been attributed to gadolinium. The face, neck, and upper trunk are typically spared (other than occasional yellow plaques in the ocular sclerae) (35).

Table 3.

The differential diagnoses of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis (24)

| Diagnosis |

|---|

| Amyloidosis |

| β2-Microglobulin amyloidosis |

| Borreliosis |

| Calciphylaxis |

| Carcinoid syndrome |

| Chronic graft vs.host disease |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans |

| Drug-induced fibrosis [silica, polyvinyl chloride, toxic (“Spanish”) oil] (33) |

| Fibroblastic rheumatism (76) |

| Lipodermatosclerosis |

| Melorheostosis |

| Early cellulitis |

| Early panniculitis |

| Eosinophilic fasciitis |

| Eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome |

| Phenylketonuria |

| Porphyria cutanea tarda |

| Pretibila myxedema |

| Progeria |

| Scleredema of Buschke |

| Scleroderma |

| Scleromyxedema (77) |

| Systemic sclerosis/morphea |

Treatment

There are no consistently effective treatments for gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis (67).

Histology and Immunohistology

The index cases of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis were detailed by Shawn Cowper and colleagues in 2000 (21). Skin biopsies demonstrate dermal fibrosis with a significant increase in cellularity, but no inflammation (59). Often the cells are described as being spindle shaped (61, 77), fibroblasts (6), fibroblast like (56), fibrohistiocytic (68, 75, 82), or “polygonal epitheliod fibroblasts” (6). With the use of light microscopy, the dermal collagen is notably increased (27), with bundles haphazardly arranged (56) or “disorganized” (48). Mucin may be present (29, 55, 61, 105), but is not required for the diagnosis (59). The abundant, thin, and spindle-shaped cells often express CD34 and type I (immature) procollagen (22, 24, 59).

Pathogenesis

Role of fibrocytes, both bone marrow derived and resident.

The histology of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis-afflicted skin is remarkable for an increase in cellularity, with CD34- and procollagen I-expressing spindle cells, occasional histiocytes, and factor XIIIa+ dendritic cells (22, 59). Among markers of hematopoietic stem cells, CD34 is one of the first identified and commonly used as such (32). It can be expressed by vascular endothelia and mesenchymal cells of myeloid origin. CD34- and collagen type I-positive cells that are recruited from the circulation have been termed “fibrocytes” (13). Fibrocytes are unique in that they are peripheral blood cells that have the potential to generate matrix and may be important in the proliferative stages of wound repair (84). Because of the symmetric nature of the disease, the rapid development of lesions, the absence of mitotic figures among the numerous spindle-shaped cells (resembling wound healing), and these cellular markers, it has been hypothesized that the fibrosis is mediated by circulating fibrocytes (20, 51, 84).

Effect of gadolinium-based contrast on fibroblasts in vitro.

The expression of α-smooth muscle actin stress fibers is an indication of an activated myofibroblast (94). When quiescent human foreskin fibroblasts are treated with a clinically relevant dose of gadodiamide (0.2 mM), they exhibit α-smooth muscle actin stress fibers in addition to an accumulation of fibronectin, a correlate of extracellular matrix accumulation. These doses of contrast do not elicit a very robust proliferative or toxic effect (26).

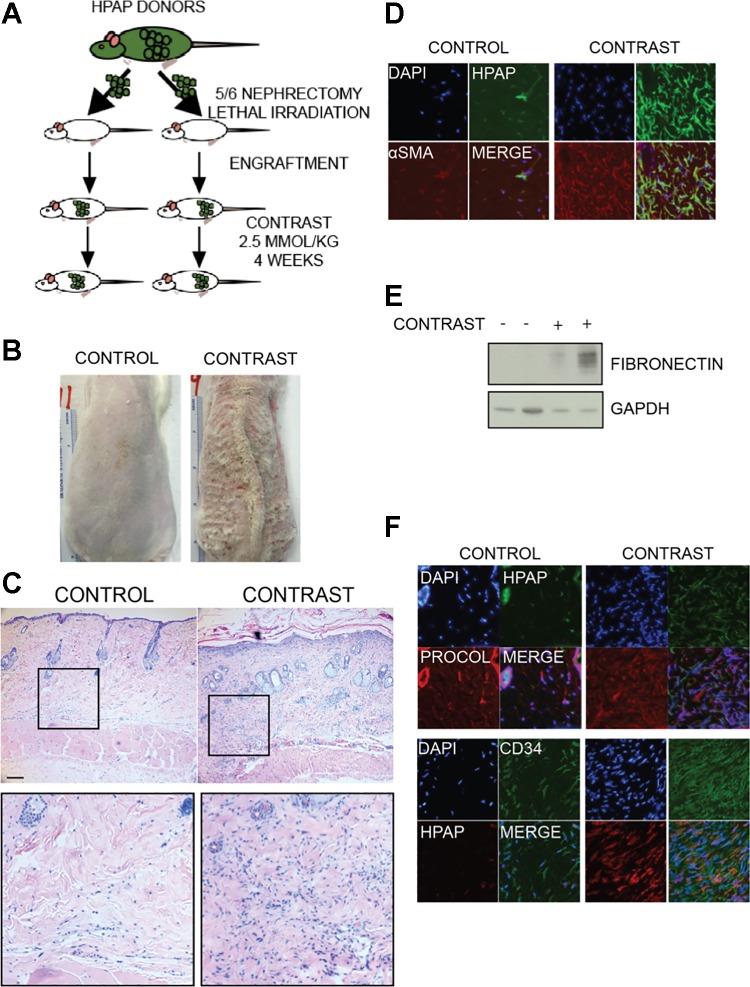

Are myeloid cells present in gadolinium-based contrast-induced fibrotic lesions?

As there was no experimental proof that the cellularity of the lesions was even partially due to circulating, bone marrow-derived fibrocytes, we conducted an experiment to test the hypothesis (101). Rats with 5/6 nephrectomies (to model renal insufficiency) underwent lethal irradiation, followed by salvage bone marrow transplantation from tagged donors (Fig. 2A). These donors expressed an antigen, the human placental alkaline phosphatase, that permitted the differentiation of myeloid from host cells in the recipients. After an engraftment period, animals were treated with gadolinium-based contrast over a 4-wk period (corresponding to the treatment duration published by Sieber and colleagues in the first rat model of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis) (90). Both the control and contrast-treated groups tolerated the entire procedure. On occasion, animals demonstrated signs of stress (e.g., periorbital porphyrin staining), and sometimes even gross skin changes (Fig. 2B). Histologically, skin from the contrast-treated animals demonstrated greater epidermal thicknesses, severe dermal fibrosis, and an increase in dermal cellularity (Fig. 2C). Immunofluorescent staining of the dermis revealed a large percentage of myeloid ells in the diseased skin from the contrast-treated animals (Fig. 2D). These cells also demonstrated a rich expression of α-smooth muscle actin stress fibers. Levels of fibronectin were increased in skin from the contrast-treated animals (Fig. 2E). Finally, the common fibrocyte markers CD34 and procollagen type I were both markedly increased in the skin from the contrast-treated animals, and each very much expressed by the myeloid cells (Fig. 2F). These experiments proved that bone marrow-derived fibroblasts comprise the lesion of gadolinium contrast-induced systemic fibrosis. However, the increase in cellularity was not entirely from myeloid cells; there is an increase in both bone marrow-derived and host/resident cells in the dermis (101).

Fig. 2.

Myeloid cells comprise much of the cellularity of gadolinium-based, contrast-induced lesions. A: it has been presupposed that bone marrow-derived circulating cells are the mediators of gadolinium contrast-induced systemic fibrosis. Transgenic rats “tagged” with a human placental alkaline phosphatase antigen served as bone marrow donors to lethally irradiated recipients with 5/6 nephrectomies (as a model of chronic kidney disease). After an engraftment period, one group was treated with gadolinium-based contrast (2.5 mmol/kg intraperitoneally daily, for a total of 20 doses over 4 wk) (101). B: this type of experiment has been conducted several times in our laboratory. Occasionally, animals will demonstrate gross dermatological changes, ranging from hyperpigmentation to punctate ulcerations and eschars. C: histologically, skin changes in rats resembles that found in humans; there is an increase in epidermal thickness, disorganized collagen bundles in the dermis, and an increase in dermal cellularity. D: dermis from the contrast-treated animals demonstrate a marked increase in myeloid cellularity. These cells often express α-smooth muscle actin-positive stress fibers. Immunofluorescence is shown of frozen skin (original magnification ×40). E: immunoblot of fibronectin, a marker of fibrosis, which is increased in the skin from contrast-treated animals. F: the fibrocyte markers procollagen type I (procol) and CD34 are increased in the dermis from contrast-treated animals. This pattern resembles what has been reported in humans afflicted with gadolinium contrast-induced systemic fibrosis. Note that some of the myeloid cells express these markers. DAPI, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; HPAP, human placental alkaline phosphatase; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin.

Comparison of “low” with “high” thermodynamic stability gadolinium-based contrast agents on severity of fibrotic lesions.

As mentioned, there are a number of different formulations of gadolinium-based contrast, and these have slightly different properties. The volumes of distribution are essentially the same, and they are excreted by the kidney. It does appear that the pinocytosis of gadolinium-bound ligands relates to the thermodynamic stability (in vitro, demonstrated in rat hepatoma and glioma cells) (14). From a nephrologist's perspective, many of us are concerned about administering gadolinium-based compounds, regardless of what narrative reviews and editorials champion, particularity with regard to the safety of one agent over another. The theories concerning why one ligand may be safer than another are entirely grounded in observational case reports and have not been subjected to a prospective experimental testing. Therefore, we treated rats with 5/6 nephrectomies with either a “low” or “high” thermodynamic stability contrast agent (i.e., gadodiamide and gadoteridol, respectively) for 4 wk (26). Again, contrast-treated animals rarely developed gross lesions. Microscopically, though, the skin from the gadodiamide-treated group again showed epidermal thickening, dermal fibrosis, and increased dermal cellularity. The increase in dermal cellularity and the markers of fibrosis were less in the animals treated with gadoteridol. However, the skin of the gadoteridol-treated animals did manifest an increase in transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1). Perhaps the degree of fibrosis would have been similar if longer durations of treatment were conducted, or if a recovery period was added to the end of the experiment. Both gadodiamide and gadoteridol induced greater dermal procollagen I, CD34, and factor XIIIa levels with respect to the untreated controls. Gadolinium was found in a number of organs in addition to the skin, yet by histology and immunofluorescence, fibrosis was not detected in many of the metal-laden organs (other than the kidney) (26). Because the liver should be a sink for liberated gadolinium, yet remains histologically intact, perhaps there is an antifibrotic mechanism that is specific to this and other organs.

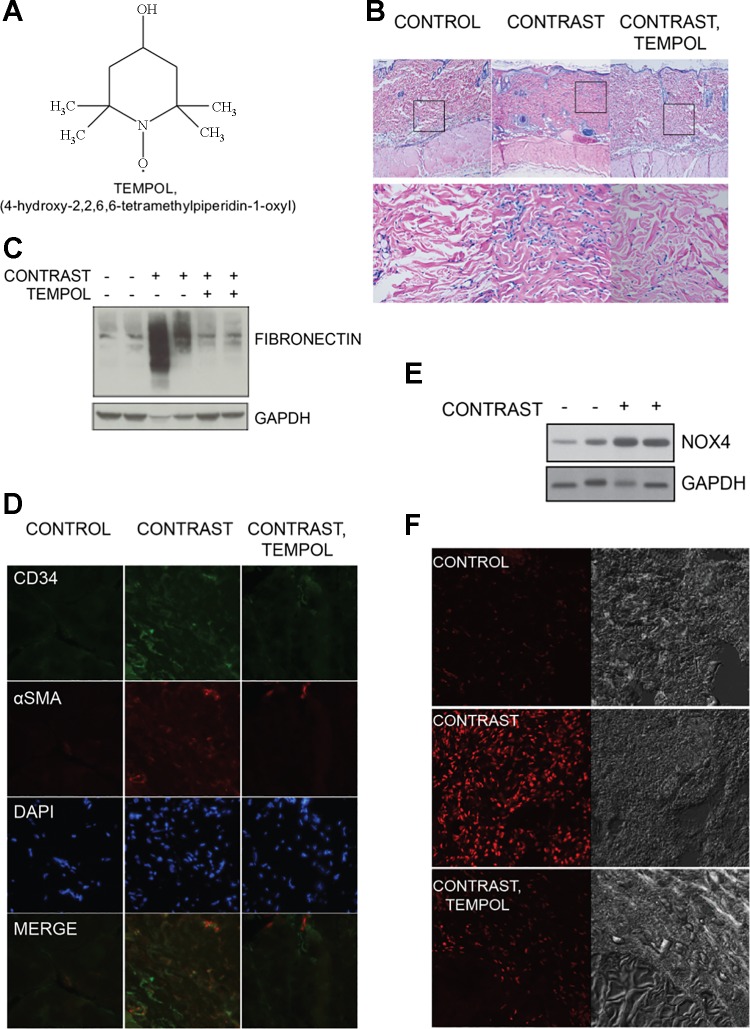

Reactive oxygen species and gadolinium-based contrast-induced fibrosis.

It has been documented that reactive oxygen species are required for the fibrogenic processes and myofibroblast activation taking place in numerous organs undergoing injury, including the kidney, the heart, the lung, and the liver (7, 57, 60, 89). In general, fibrosis is a pathological response typically preceded by damage to the endothelial/epithelial barriers, the release of TGF-β1, the recruitment of inflammatory cells, the induction of reactive oxygen species, and the deposition of collagen and extracellular matrix (58). The generation of reactive oxygen species may mediate the transdifferentiation of myofibroblast progenitor cells (46). Profibrotic pathways are redox dependent in numerous cell types, including fibroblasts (39, 100). Therefore, we examined the effect of a superoxide dismutase mimetic, tempol (104), on gadolinium-induced systemic fibrosis (Fig. 3A) (101). Again, when comparing the contrast-treated with the control animals, the former demonstrated thickening of the epidermal layers and a great increase in dermal cellularity (Fig. 3B). When contrast-treated animals were given tempol, the fibrosis and dermal cellularity were greatly attenuated. The same effect was apparent with skin fibronectin quantity (Fig. 3C): tempol abrogated the contrast-induced increase. Similarly, contrast-induced increases in dermal CD34 and cells expressing α-smooth muscle actin-containing stress fibers were reduced by tempol coadministration (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Reactive oxygen species mediate gadolinium contrast-induced systemic fibrosis. A: tempol, a superoxide dismutase mimetic, was concomitantly administered (in the drinking water) to rats in a model of contrast-induced fibrosis (101). B: skin from rats treated with magnetic resonance imaging contrast showed dermal fibrosis and an increase in dermal cellularity. This effect was abrogated in the group where tempol was coadministered. Hematoxylin and eosin: top, ×10 objective; bottom, ×40 objective. Calibration bar = 0.05 mm. C: gadolinium contrast-induced skin fibronectin is normalized by coadministration of tempol. D: tempol suppresses the gadolinium-based contrast increases of dermal fibrocyte marker CD34 and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) positive stress fibers. E: magnetic resonance imaging contrast increases skin NADPH oxidase isoform 4 (Nox4) levels. F: animals that received tempol demonstrated less oxidative stress than those subjected to magnetic resonance contrast alone.

The reactive oxygen species generated by the NADPH oxidases of the Nox family have been involved as key mediators of renal, cardiac, lung and liver fibrosis (7, 37, 41, 65). To date, the Nox family comprises seven members: Nox1–Nox5, dual oxidase (Duox) 1, and Duox2 (36, 37, 40). We noted that the expression of NADPH oxidase isoform Nox4 in the skin, but not that of Nox2 and Nox1 isoforms, paralleled the increase of fibronectin when animals were treated with gadolinium contrast (Fig. 3E). Notably, evidence of oxidative stress in the dermis, measured by dihydroethidium staining, was suppressed in the contrast-treated animals given tempol (with respect to the animals given contrast only, Fig. 3F). Therefore, the generation of reactive oxygen species, possibly by Nox4, may be an early mediator of the fibrotic process.

Interestingly, a wide array of evidence shows that Nox4-derived reactive oxygen species play a major role in the pathogenesis of renal, cardiac, lung, and liver fibrosis (9, 36, 37, 40, 45, 49, 63, 65). Importantly, Nox4 has also been reported to be a primary target of TGF-β and a critical mediator of its profibrotic actions in various cell types (7, 36, 40, 45). It should be pointed out that pharmacological inhibitors of Nox4 are available and have undergone preclinical studies in animal models of fibrotic diseases, where they successfully attenuated the pathological changes observed in renal complication of diabetes, atherosclerosis, liver fibrosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (5, 9, 36, 37, 40, 49, 50, 63). Therefore, Nox4 may represent an attractive therapeutic target for prophylaxis or the treatment of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis.

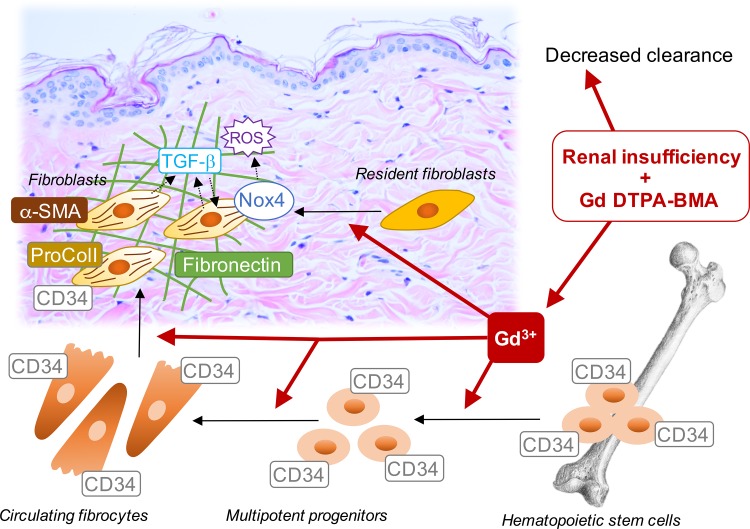

Overall, we have demonstrated that gadolinium-based contrast administration in rats can reproduce the pathology of systemic fibrosis witnessed in humans. Perhaps decreased renal elimination of the gadolinium-ligand complex promotes the liberation of gadolinium as an initial step, but this still has yet to be experimentally proven. The next conjecture is that gadolinium deposition in tissue initiates the release of profibrotic chemokines. Regardless, we do have the experimental proof that there is a recruitment of myeloid spindle-shaped cells concomitant with increases in CD34, α-smooth muscle actin stress fibers, and procollagen I (as well as collagen types I and IV, and factor XIIIa) (101). Our hypothesis is that the generation of reactive oxygen species is involved in gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis. The fact that dermal Nox4 is concomitantly increased (unlike other Nox isoforms), together with its status as key player in organ fibrosis, implicates this protein not only as an early mediator of the disease, but also as a therapeutic target. There are small molecular inhibitors specific to Nox4 that successfully passed phase I clinical trial and are currently being tested for the mitigation of diabetic nephropathy in phase II studies (38) that may prove to be prophylactic or therapeutic for this condition, too. Figure 4 depicts the possible molecular mechanisms implicated in gadolinium-based contrast induced fibrosis.

Fig. 4.

Possible molecular mechanisms underlying gadolinium-based, contrast-induced systemic fibrosis. See text for details.

Conclusions

Gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis is a rare condition. From 1997 to 2009, the number of cases increased from 15 to 304 (18, 21). The incidence of contrast-induced fibrosis is declining, as patients with renal disease are being excluded from gadolinium-enhanced studies. In one retrospective study of patients referred to an academic nephrology subspecialty group, a remarkable 18% were diagnosed with the disorder (69).

The discovery that gadolinium-based magnetic resonance imaging contrast, combined with renal impairment, is a strong risk factor for systemic fibrosis has led to drastic changes in how diagnosticians approach patients. Gadolinium-based contrast-induced systemic fibrosis is a chronic, incurable, and ghastly disease that leads to extreme suffering, increased morbidity, and increased mortality. Those at risk are a subset already burdened by chronic disease, compounding the tragedy. It is estimated that over 20 million United States citizens are afflicted with renal disease. That patients with renal insufficiency will be exposed to gadolinium-based contrast remains a risk. Because so little is known about this new and iatrogenic disease, clinicians need to be guarded. How gadolinium accelerates and directs skin fibrosis only in the milieu of renal insufficiency will provide us an opportunity to design better gadolinium-based contrast agents, provide information about the physiology of scarring and the pathophysiology of other sclerotic conditions, and could lead to improvements in the understanding of wound healing: this is still a knot that needs unraveling.

GRANTS

The research was funded by the Veterans Administration Merit Award (I01 BX001958, B. Wagner); the National Institutes of Health through Grants R01 DK-102085 (B. Wagner), UL1 TR-001120 (Y. Gorin), R01 DK-079996 (Y. Gorin), and R01 DK-78971 (Y. Gorin); and an award from the Qatar National Research Fund, National Priorities Research Program (NPRP8-1750-3-360) (Y. Gorin).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.W. conception and design of research; B.W. performed experiments; B.W. analyzed data; B.W. interpreted results of experiments; B.W. and Y.G. prepared figures; B.W. drafted manuscript; B.W., V.D., and Y.G. edited and revised manuscript; B.W., V.D., and Y.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abujudeh HH, Kaewlai R, Kagan A, Chibnik LB, Nazarian RM, High WA, Kay J. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after gadopentetate dimeglumine exposure: case series of 36 patients. Radiology 253: 81–89, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal R, Brunelli SM, Williams K, Mitchell MD, Feldman HI, Umscheid CA. Gadolinium-based contrast agents and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 856–863, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aime S, Caravan P. Biodistribution of gadolinium-based contrast agents, including gadolinium deposition. J Magn Reson Imaging 30: 1259–1267, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anavekar NS, Chong AH, Norris R, Dowling J, Goodman D. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in a gadolinium-naive renal transplant recipient. Australas J Dermatol 49: 44–47, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aoyama T, Paik YH, Watanabe S, Laleu B, Gaggini F, Fioraso-Cartier L, Molango S, Heitz F, Merlot C, Szyndralewiez C, Page P, Brenner DA. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase in experimental liver fibrosis: GKT137831 as a novel potential therapeutic agent. Hepatology 56: 2316–2327, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auron A, Shao L, Warady BA. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy in children. Pediatr Nephrol 21: 1307–1311, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes JL, Gorin Y. Myofibroblast differentiation during fibrosis: role of NAD(P)H oxidases. Kidney Int 79: 944–956, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bau M, Dulski P. Anthropogenic origin of positive gadolinium anomalies in river waters. Earth Planet Sci Lett 143: 245–255, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bettaieb A, Jiang JX, Sasaki Y, Chao TI, Kiss Z, Chen X, Tian J, Katsuyama M, Yabe-Nishimura C, Xi Y, Szyndralewiez C, Schroder K, Shah A, Brandes RP, Haj FG, Torok NJ. Hepatocyte nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced oxidase 4 regulates stress signaling, fibrosis, and insulin sensitivity during development of steatohepatitis in mice. Gastroenterology 149: 468–480 e410, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boin F, Hummers LK. Scleroderma-like fibrosing disorders. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 34: 199–220; ix, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bremmer M, Deng A, Martin DB. Spontaneous eruptive keloid-like cutaneous lesions in a renal transplant patient: a form of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? J Dermatolog Treat 20: 63–66, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broome DR, Girguis MS, Baron PW, Cottrell AC, Kjellin I, Kirk GA. Gadodiamide-associated nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: why radiologists should be concerned. AJR Am J Roentgenol 188: 586–592, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bucala R, Spiegel LA, Chesney J, Hogan M, Cerami A. Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Mol Med 1: 71–81, 1994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabella C, Crich SG, Corpillo D, Barge A, Ghirelli C, Bruno E, Lorusso V, Uggeri F, Aime S. Cellular labeling with Gd(III) chelates: only high thermodynamic stabilities prevent the cells acting as “sponges” of Gd3+ ions. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 1: 23–29, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canavese C, Mereu MC, Aime S, Lazzarich E, Fenoglio R, Quaglia M, Stratta P. Gadolinium-associated nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: the need for nephrologists' awareness. J Nephrol 21: 324–336, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheung PP, Dorai Raj AK. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: a new clinical entity mimicking scleroderma. Intern Med J 37: 139–141, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collidge TA, Thomson PC, Mark PB, Traynor JP, Jardine AG, Morris ST, Simpson K, Roditi GH. Gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: retrospective study of a renal replacement therapy cohort. Radiology 245: 168–175, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cowper S. Joint Meeting of the Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs and Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committees (Online). US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/CardiovascularandRenalDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM196233.pdf 2/18/2016.

- 19.Cowper SE. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (Online). The International Center for Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis Research (ICNSFR), Yale University, New Haven, CT. http://www.icnfdr.org [24 March 2009].

- 20.Cowper SE, Bucala R. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: suspect identified, motive unclear. Am J Dermatopathol 25: 358, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cowper SE, Robin HS, Steinberg SM, Su LD, Gupta S, LeBoit PE. Scleromyxoedema-like cutaneous diseases in renal-dialysis patients. Lancet 356: 1000–1001, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cowper SE, Su LD, Bhawan J, Robin HS, LeBoit PE. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol 23: 383–393, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dawson P. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: possible mechanisms and imaging management strategies. J Magn Reson Imaging 28: 797–804, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeHoratius DM, Cowper SE. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: an emerging threat among renal patients. Semin Dial 19: 191–194, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deo A, Fogel M, Cowper SE. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a population study examining the relationship of disease development to gadolinium exposure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 264–267, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Do C, Barnes JL, Tan C, Wagner B. Type of MRI contrast, tissue gadolinium, and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 307: F844–F855, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dupont A, Majithia V, Ahmad S, McMurray R. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy, a new mimicker of systemic sclerosis. Am J Med Sci 330: 192–194, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ersoy H, Rybicki FJ. Biochemical safety profiles of gadolinium-based extracellular contrast agents and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Magn Reson Imaging 26: 1190–1197, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Firoz BF, Hunzeker CM, Soldano AC, Franks AG Jr. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Dermatol Online J 14: 11, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foti R, Leonardi R, Rondinone R, Di Gangi M, Leonetti C, Canova M, Doria A. Scleroderma-like disorders. Autoimmun Rev 7: 331–339, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frenzel T, Lengsfeld P, Schirmer H, Hutter J, Weinmann HJ. Stability of gadolinium-based magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents in human serum at 37°C. Invest Radiol 43: 817–828, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furness SG, McNagny K. Beyond mere markers: functions for CD34 family of sialomucins in hematopoiesis. Immunol Res 34: 13–32, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galan A, Cowper SE, Bucala R. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy). Curr Opin Rheumatol 18: 614–617, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilchrest BA, Rowe JW, Mihm MC Jr. Clinical and histological skin changes in chronic renal failure: evidence for a dialysis-resistant, transplant-responsive microangiopathy. Lancet 2: 1271–1275, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Girardi M, Kay J, Elston DM, Leboit PE, Abu-Alfa A, Cowper SE. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: clinicopathological definition and workup recommendations. J Am Acad Dermatol 65: 1095–1106 e1097, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorin Y, Block K. Nox4 and diabetic nephropathy: with a friend like this, who needs enemies? Free radical biology & medicine 61C: 130–142, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorin Y, Block K. Nox as a target for diabetic complications. Clin Sci (Lond) 125: 361–382, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorin Y, Cavaglieri RC, Khazim K, Lee DY, Bruno F, Thakur S, Fanti P, Szyndralewiez C, Barnes JL, Block K, Abboud HE. Targeting NADPH oxidase with a novel dual Nox1/Nox4 inhibitor attenuates renal pathology in type 1 diabetes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 308: F1276–F1287, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorin Y, Ricono JM, Wagner B, Kim NH, Bhandari B, Choudhury GG, Abboud HE. Angiotensin II-induced ERK1/ERK2 activation and protein synthesis are redox-dependent in glomerular mesangial cells. Biochem J 381: 231–239, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorin Y, Wauquier F. Upstream regulators and downstream effectors of NADPH oxidases as novel therapeutic targets for diabetic kidney disease. Mol Cells 38: 285–296, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffith B, Pendyala S, Hecker L, Lee PJ, Natarajan V, Thannickal VJ. NOX enzymes and pulmonary disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 2505–2516, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grobner T. Gadolinium–a specific trigger for the development of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 1104–1108, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gulati A, Harwood CA, Raftery M, Cerio R, Ashman N, Proby CA. Magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium enhancement in renal failure: a need for caution. Int J Dermatol 47: 947–949, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haylor J, Dencausse A, Vickers M, Nutter F, Jestin G, Slater D, Idee JM, Morcos S. Nephrogenic gadolinium biodistribution and skin cellularity following a single injection of Omniscan in the rat. Invest Radiol 45: 507–512, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hecker L, Vittal R, Jones T, Jagirdar R, Luckhardt TR, Horowitz JC, Pennathur S, Martinez FJ, Thannickal VJ. NADPH oxidase-4 mediates myofibroblast activation and fibrogenic responses to lung injury. Nat Med 15: 1077–1081, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Galli A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast: one function, multiple origins. Am J Pathol 170: 1807–1816, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Idee JM, Port M, Raynal I, Schaefer M, Le Greneur S, Corot C. Clinical and biological consequences of transmetallation induced by contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging: a review. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 20: 563–576, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Introcaso CE, Hivnor C, Cowper S, Werth VP. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy/nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a case series of nine patients and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol 46: 447–452, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jha JC, Gray SP, Barit D, Okabe J, El-Osta A, Namikoshi T, Thallas-Bonke V, Wingler K, Szyndralewiez C, Heitz F, Touyz RM, Cooper ME, Schmidt HH, Jandeleit-Dahm KA. Genetic targeting or pharmacologic inhibition of NADPH oxidase nox4 provides renoprotection in long-term diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1237–1254, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang JX, Chen X, Serizawa N, Szyndralewiez C, Page P, Schroder K, Brandes RP, Devaraj S, Torok NJ. Liver fibrosis and hepatocyte apoptosis are attenuated by GKT137831, a novel NOX4/NOX1 inhibitor in vivo. Free Radic Biol Med 53: 289–296, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jimenez SA, Artlett CM, Sandorfi N, Derk C, Latinis K, Sawaya H, Haddad R, Shanahan JC. Dialysis-associated systemic fibrosis (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy): study of inflammatory cells and transforming growth factor beta1 expression in affected skin. Arthritis Rheum 50: 2660–2666, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kadiyala D, Roer DA, Perazella MA. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis associated with gadoversetamide exposure: treatment with sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 133–137, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kallen AJ, Jhung MA, Cheng S, Hess T, Turabelidze G, Abramova L, Arduino M, Guarner J, Pollack B, Saab G, Patel PR. Gadolinium-containing magnetic resonance imaging contrast and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a case-control study. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 966–975, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kay J. Gadolinium and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: the evidence of things not seen. Cleve Clin J Med 75: 112–117, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kay J, High WA. Imatinib mesylate treatment of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum 58: 2543–2548, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim RH, Ma L, Hayat SQ, Ahmed MM. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy/nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in 2 patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis. J Clin Rheumatol 12: 134–136, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kinnula VL, Myllarniemi M. Oxidant-antioxidant imbalance as a potential contributor to the progression of human pulmonary fibrosis. Antioxid Redox Signal 10: 727–738, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kisseleva T, Brenner DA. Mechanisms of fibrogenesis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 233: 109–122, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knopp EA, Cowper SE. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: early recognition and treatment. Semin Dial 21: 123–128, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kong P, Christia P, Frangogiannis NG. The pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis. Cell Mol Life Sci 71: 549–574, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kucher C, Steere J, Elenitsas R, Siegel DL, Xu X. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy/nephrogenic systemic fibrosis with diaphragmatic involvement in a patient with respiratory failure. J Am Acad Dermatol 54: S31–S34, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kurtkoti J, Snow T, Hiremagalur B. Gadolinium and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: association or causation. Nephrology (Carlton) 13: 235–241, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lan T, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA. Deficiency of NOX1 or NOX4 prevents liver inflammation and fibrosis in mice through inhibition of hepatic stellate cell activation. PLoS One 10: e0129743, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lawrence MG. Detection of anthropogenic gadolinium in the Brisbane River plume in Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia. Mar Pollut Bull 60: 1113–1116, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liang S, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA. The role of NADPH oxidases (NOXs) in liver fibrosis and the activation of myofibroblasts. Front Physiol 7: 17, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin SP, Brown JJ. MR contrast agents: physical and pharmacologic basics. J Magn Reson Imaging 25: 884–899, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Linfert DR, Schell JO, Fine DM. Treatment of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: limited options but hope for the future. Semin Dial 21: 155–159, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maloo M, Abt P, Kashyap R, Younan D, Zand M, Orloff M, Jain A, Pentland A, Scott G, Bozorgzadeh A. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis among liver transplant recipients: a single institution experience and topic update. Am J Transplant 6: 2212–2217, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marckmann P. An epidemic outbreak of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in a Danish hospital. Eur J Radiol 66: 187–190, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marckmann P, Skov L, Rossen K, Dupont A, Damholt MB, Heaf JG, Thomsen HS. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: suspected causative role of gadodiamide used for contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2359–2362, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marckmann P, Skov L, Rossen K, Thomsen HS. Clinical manifestation of gadodiamide-related nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Clin Nephrol 69: 161–168, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martin DR. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Pediatr Radiol 38, Suppl 1: S125–S129, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mathur K, Morris S, Deighan C, Green R, Douglas KW. Extracorporeal photopheresis improves nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy/nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: three case reports and review of literature. J Clin Apheresis 23: 144–150, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McDonald RJ, McDonald JS, Kallmes DF, Jentoft ME, Murray DL, Thielen KR, Williamson EE, Eckel LJ. Intracranial gadolinium deposition after contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology 275: 772–782, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moreno-Romero JA, Segura S, Mascaro JM Jr, Cowper SE, Julia M, Poch E, Botey A, Herrero C. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a case series suggesting gadolinium as a possible aetiological factor. Br J Dermatol 157: 783–787, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moschella SL, Kay J, Mackool BT, Liu V. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 35–2004. A 68-year-old man with end-stage renal disease and thickening of the skin. N Engl J Med 351: 2219–2227, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Neudecker BA, Stern R, Mark LA, Steinberg S. Scleromyxedema-like lesions of patients in renal failure contain hyaluronan: a possible pathophysiological mechanism. J Cutan Pathol 32: 612–615, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ng YY, Lee RC, Shen SH, Kirk G. Gadolinium-associated nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: double dose, not single dose. AJR Am J Roentgenol 188: W582; author reply W583, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Othersen JB, Maize JC, Woolson RF, Budisavljevic MN. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after exposure to gadolinium in patients with renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 3179–3185, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Perazella MA. How should nephrologists approach gadolinium-based contrast imaging in patients with kidney disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 649–651, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Port M, Idee JM, Medina C, Robic C, Sabatou M, Corot C. Efficiency, thermodynamic and kinetic stability of marketed gadolinium chelates and their possible clinical consequences: a critical review. Biometals 21: 469–490, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pryor JG, Poggioli G, Galaria N, Gust A, Robison J, Samie F, Hanjani NM, Scott GA. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a clinicopathologic study of six cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 57: 105–111, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Puttagunta NR, Gibby WA, Smith GT. Human in vivo comparative study of zinc and copper transmetallation after administration of magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Invest Radiol 31: 739–742, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Quan TE, Cowper S, Wu SP, Bockenstedt LK, Bucala R. Circulating fibrocytes: collagen-secreting cells of the peripheral blood. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 36: 598–606, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Reilly RF. Risk for nephrogenic systemic fibrosis with gadoteridol (ProHance) in patients who are on long-term hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 747–751, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rosenkranz AR, Grobner T, Mayer GJ. Conventional or gadolinium containing contrast media: the choice between acute renal failure or nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Wien Klin Wochenschr 119: 271–275, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sanyal S, Marckmann P, Scherer S, Abraham JL. Multiorgan gadolinium (Gd) deposition and fibrosis in a patient with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis–an autopsy-based review. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 3616–3626, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sherry AD, Caravan P, Lenkinski RE. Primer on gadolinium chemistry. J Magn Reson Imaging 30: 1240–1248, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Siani A, Tirelli N. Myofibroblast differentiation: main features, biomedical relevance, and the role of reactive oxygen species. Antioxid Redox Signal 21: 768–785, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sieber MA, Lengsfeld P, Frenzel T, Golfier S, Schmitt-Willich H, Siegmund F, Walter J, Weinmann HJ, Pietsch H. Preclinical investigation to compare different gadolinium-based contrast agents regarding their propensity to release gadolinium in vivo and to trigger nephrogenic systemic fibrosis-like lesions. Eur Radiol 18: 2164–2173, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Smith HW. Lectures on the Kidney. Manhattan, KS: University Extension Division, University of Kansas, 1943. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Spencer AJ, Wilson SA, Batchelor J, Reid A, Rees J, Harpur E. Gadolinium chloride toxicity in the rat. Toxicol Pathol 25: 245–255, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Todd DJ, Kagan A, Chibnik LB, Kay J. Cutaneous changes of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: predictor of early mortality and association with gadolinium exposure. Arthritis Rheum 56: 3433–3441, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 349–363, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tsushima Y, Takahashi-Taketomi A, Endo K. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in Japan: advisability of keeping the administered dose as low as possible. Radiology 247: 915–916, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tweedle MF, Hagan JJ, Kumar K, Mantha S, Chang CA. Reaction of gadolinium chelates with endogenously available ions. Magn Reson Imaging 9: 409–415, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tweedle MF, Wedeking P, Kumar K. Biodistribution of radiolabeled, formulated gadopentetate, gadoteridol, gadoterate, and gadodiamide in mice and rats. Invest Radiol 30: 372–380, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.van der Molen AJ. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and the role of gadolinium contrast media. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 52: 339–350, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wadas TJ, Sherman CD, Miner JH, Duncan JR, Anderson CJ. The biodistribution of [153Gd]Gd-labeled magnetic resonance contrast agents in a transgenic mouse model of renal failure differs greatly from control mice. Magn Reson Med 64: 1274–1280, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wagner B, Ricono JM, Gorin Y, Block K, Arar M, Riley D, Choudhury GG, Abboud HE. Mitogenic signaling via platelet-derived growth factor beta in metanephric mesenchymal cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2903–2911, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wagner B, Tan C, Barnes JL, Ahuja SS, Davis TL, Gorin Y, Jimenez F. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: evidence for bone marrow-derived fibrocytes in skin, liver, and heart lesions using a 5/6 nephrectomy rodent model. Am J Pathol 181: 1941–1952, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wahba IM, Simpson EL, White K. Gadolinium is not the only trigger for nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: insights from two cases and review of the recent literature. Am J Transplant 7: 2425–2432, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wertman R, Altun E, Martin DR, Mitchell DG, Leyendecker JR, O'Malley RB, Parsons DJ, Fuller ER 3rd, Semelka RC. Risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: evaluation of gadolinium chelate contrast agents at four American universities. Radiology 248: 799–806, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wilcox CS. Effects of tempol and redox-cycling nitroxides in models of oxidative stress. Pharmacol Ther 126: 119–145, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zelasko S, Hollingshead M, Castillo M, Bouldin TW. CT and MR imaging of progressive dural involvement by nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 29: 1880–1882, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]