Abstract

Alport syndrome is a familial kidney disease caused by defects in the collagen type IV network of the glomerular basement membrane. Lack of collagen-α3α4α5(IV) changes the glomerular basement membrane morphologically and functionally, rendering it leaky to albumin and other plasma proteins. Filtered albumin has been suggested to be a cause of the glomerular and tubular injuries observed at advanced stages of Alport syndrome. To directly investigate the role that albumin plays in the progression of disease in Alport syndrome, we generated albumin knockout (Alb−/−) mice to use as a tool for removing albuminuria as a component of kidney disease. Mice lacking albumin were healthy and indistinguishable from control littermates, although they developed hypertriglyceridemia. Dyslipidemia was observed in Alb+/− mice, which displayed half the normal plasma albumin concentration. Alb mutant mice were bred to collagen-α3(IV) knockout (Col4a3−/−) mice, which are a model for human Alport syndrome. Lack of circulating and filtered albumin in Col4a3−/−;Alb−/− mice resulted in dramatically improved kidney disease outcomes, as these mice lived 64% longer than did Col4a3−/−;Alb+/+ and Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice, despite similar blood pressures and serum triglyceride levels. Further investigations showed that the absence of albumin correlated with reduced transforming growth factor-β1 signaling as well as reduced tubulointerstitial, glomerular, and podocyte pathology. We conclude that filtered albumin is injurious to kidney cells in Alport syndrome and perhaps in other proteinuric kidney diseases, including diabetic nephropathy.

Keywords: albumin, Alport syndrome, collagen type IV

alport syndrome is one of the best studied familial kidney diseases due to its well-defined inheritance patterns, well-established clinical presentation, and the availability of multiple animal models. Alport syndrome is caused by the lack of or defects in collagen-α3α4α5(IV) heterotrimers due to mutations in the encoding genes (Col4a3, Col4a4, or Col4a5, respectively). The distribution of this collagen dictates the clinical symptoms; in addition to neurosensory hearing loss and occasional eye abnormalities, kidney disease is ubiquitous in affected individuals. Patients are usually diagnosed due to microscopic hematuria early in life. Later, as the disease progresses, there is increasing albuminuria and kidney dysfunction that culminates in end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). Whether filtered albumin plays a role in kidney pathology in Alport syndrome is not clear and has not been directly investigated.

In vitro experiments have shown that albumin overload induces both tubular cell and podocyte injury. Exposing proximal tubular cells (PTCs) to high concentrations of albumin in vitro leads to the upregulation of several important injury signals, including transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, EGF, NF-kB, ERK, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL)2 (monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), and CCL5 (regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted) (6, 10, 11, 14, 16, 22, 34, 38, 40, 43). High albumin concentrations induce NF-κB and endothelin-1 expression in podocytes and cause significant morphological and cytoskeletal changes and cell death (31, 35). In vivo, albumin overload is associated with podocyte foot process effacement (12), increased oxidative stress, upregulation of TGF-β1, and impaired podocyte regeneration (1, 37, 42, 44).

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors have been proven to be therapeutically beneficial in Alport syndrome patients, an outcome predicted by studies in animal models (19, 20, 25). Treatment of Col4a3 knockout (Col4a3−/−) mice on the 129Sv genetic background with ramipril almost doubles their life expectancy (19). This protective effect was interpreted to be independent of lowering blood pressure (BP), although it was associated with delaying and reducing the proteinuria associated with Alport syndrome. The results of this study were later validated in a cohort of Alport syndrome patients (20), but these studies do not answer the question as to whether the improvement in outcome is dependent on reducing the albuminuria and its presumed harmful effects or whether the improvement in albuminuria is secondary and does not contribute to the protective effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition.

It is important to note that albuminuria does not always appear to be injurious. Despite heavy proteinuria, minimal change disease and some cases of membranous nephropathy are not associated with significant tubulointerstitial injury, glomerulosclerosis, or deterioration of kidney function. More intriguing are the data obtained from studies of the mutant Nagase analbuminemic rat (NAR), a spontaneous albumin gene (Alb) mutant that arose in a Sprague-Dawley colony (32). NARs are healthy, fertile, lack significant edema, and have a normal lifespan. Analbuminemia has also been described in humans (5, 26, 33). Both analbuminemic human subjects and NARs develop compensatory increases in other plasma proteins as well as hypertriglyceridemia, which are thought to help maintain oncotic pressure.

Compared with Sprague-Dawley rats, NARs do not develop age-related glomerular glomerulosclerosis, a protective effect attributed to lower systemic BP and glomerular filtration pressure (17, 18). However, the lack of albumin and albuminuria do not prevent the development of kidney disease (2, 17, 18, 27, 33, 36); in fact, after 5/6 nephrectomy, NARs develop worse glomerular hypertension, hyperfiltration, and glomerulosclerosis compared with control Sprague-Dawley rats (18). In other models of kidney disease, such as puromycin aminonucleoside nephrosis and adriamycin-induced glomerulosclerosis, NARs develop the same degree of glomerular and podocyte abnormalities (2, 36).

To investigate albumin's toxicity in Alport syndrome, we generated an albumin-null mouse. We used it to study the contribution of albumin and albuminuria to kidney disease progression in our well-characterized mouse model of Alport syndrome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Albumin Knockout Mice

All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee.

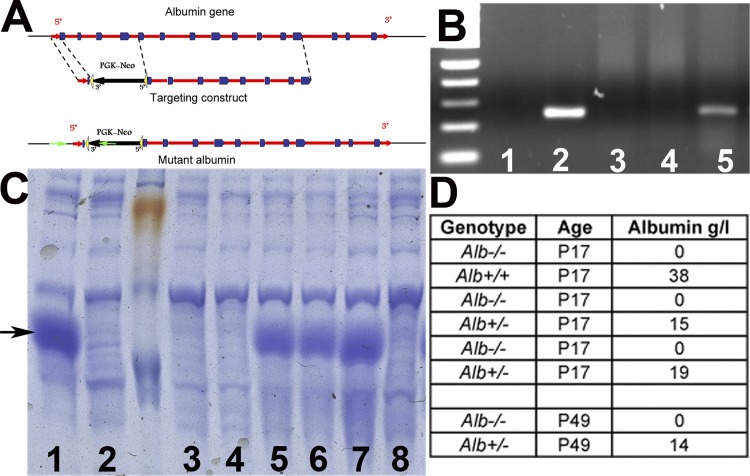

The Alb gene was disrupted by replacing the first four exons with a PGK-neo selectable marker placed in the opposite transcriptional orientation (Fig. 1A). For initial phenotypic characterization, Alb+/− mice were intercrossed to generate Alb−/− mice on a mixed 129/B6 strain background. Genotyping was performed using the following primers: Alb mutant allele 5′-GAAGGCCCAGGGCTCGCAGCCAACGTC-3′ and 5′-GCTCAAATGGGAGACAAAGAG-3′ and Alb wild-type (WT) allele 5′-CCACAGACAAGAGTGAGATCGC-3′ and 5′-GCCTTGTGATCTCTGGCTGCCA-3′. For combined Alport mouse experiments, the Alb mutation was backcrossed to C57BL/6J for at least 10 generations.

Fig. 1.

Generation of albumin knockout (Alb−/−) mice and verification of the lack of albumin. A: schematic diagrams showing the Alb gene, the Alb targeting construct designed to eliminate four 5′-exons, and the targeted locus. Green arrows indicate the location of primers used to identify the mutant allele. B: RT-PCR from Alb−/− mouse liver RNA showing the lack of albumin mRNA. Lane 1, negative control (RNA from a normal liver without reverse transcriptase reaction); lane 2, wild-type (WT) liver; lane 3, Alb−/− liver; lane 4, normal spleen; lane 5, Alb+/− liver. C: SDS-PAGE analysis of 0.1 μl serum from Alb+/+ (lanes 1 and 7), Alb+/− (lanes 5 and 6), and Alb−/− (lanes 2–4 and 8) mice showing the complete lack of the dense albumin band in Alb−/− sera. Arrow points to the 67-kDa albumin band D: serum albumin concentrations in mice as measured by ELISA. Alb−/− mice had no albumin and Alb+/− mice had reduced albumin. None developed the ascites or subcutaneous edema commonly associated with hypoalbuminemia. Ages were measured in postnatal days (P).

Genetically Altered Mice and Analysis of Fluids

Col4a3tm1Jhm (Col4a3−/−) Alport mice on the C57BL/6J background have been previously described (4, 30). They have been backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice for over 20 generations. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was measured with a kit from Bioassay Systems (Hayward, CA). Serum lipids were analyzed in nonfasting mice fed normal chow by the Nutrition Obesity Research Center's Animal Model Research Core at Washington University School of Medicine.

Intravascular BP Measurements

Mice were anesthetized with 1% isoflurane inhaled through a nose cone and kept warm by radiant heat. A catheter (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) was inserted into the right common carotid artery, and the mean heart rate and systolic, diastolic, and mean pressures were recorded for 5 min (41).

Survival Analysis

Mice were monitored frequently for signs of illness or weight loss. Mice showing signs of illness or loss of >15% of peak body weight were euthanized and counted as early mortality/ESKD. Any unexpected mortality was also counted. If a mouse was euthanized as a control (regardless of the genotype) for an ill mouse, it was not considered as a mortality. The survival curve included 14 Col4a3−/−;Alb+/+ mice, 15 Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice, and 6 Col4a3−/−;Alb−/− double knockout (DKO) mice. Many healthy looking DKO mice were euthanized before becoming ill to serve as appropriate age-matched comparisons for their ill littermates. Survival analysis was performed using PRISM software using both logrank and Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon tests. The reported median and P values are from the logrank test, although both methods showed consistent results.

Histology

Light microscopy.

Kidneys were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 h followed by a wash in PBS and dehydration in graded ethanols. Tissues were embedded in paraffin, and 2-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, or trichrome. To quantitate the severity of tubulointerstitial injury, we followed standard pathological practices and rated it as minimal (<5% of the tubulointerstitium is involved), mild (5–25%), moderate (25–50%), or severe (>50%).

To estimate the extent of glomerulosclerosis, we photographed a cross section from two kidneys from three animals from each of the genotypes at ×40 magnification. A blinded observer counted the total number and number of globally and segmentally sclerotic glomeruli to calculate the percentage of globally and segmentally sclerotic glomeruli.

Electron microscopy.

Small pieces of kidneys were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, embedded, and then visualized according to our previously published methods (23, 28). To measure the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) width, we photographed multiple capillary loops from four to five glomeruli from each animal group at high magnification (between 3 and 15K). We used Olympus Cell Sens imaging software to measure the width of the GBM by drawing a perpendicular line across the GBM from the cell membrane of the podocytes to that of endothelial cells at regular intervals and then converted these measurements into nanometers. We avoided areas corresponding to the mesangium and avoided using any image if the GBM was not cut perpendicularly.

Antibodies and Immunofluorescence

Seven-micrometer sections of fresh frozen kidneys were used for all immunofluorescence experiments. A list of primary antibodies as well as the fixation methods are shown in Table 1. Immunofluorescence procedures followed those in our previously published study (28). Apoptosis was assayed by a TUNEL kit purchased from Roche.

Table 1.

Antibodies and staining conditions

| Antigen | Name/Number | Source | Fixation |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Smooth muscle actin | ab5694 | Abcam | Unfixed/paraformaldehyde |

| CD68 | FA-11 | AbD Serotec | Unfixed |

| Collagen-α2(IV) | H22 | Yoshikazu Sado (Shigei Medical Research Institute) | Acetone/urea glycine |

| Desmin | D33 | DAKO | Unfixed |

| Nidogen | MAB1946 | EMD Millipore | Unfixed/paraformaldehyde |

| Fibronectin | F3648 | Sigma | Unfixed |

| Kidney injury molecule-1 | AF3689 | R&D Systems | Paraformaldehyde |

| Laminin-111 | L9393 | Sigma | Unfixed/paraformaldehyde |

| Laminin-α5 | Ref. 29 | Unfixed | |

| Laminin-β2 | 1117 | Gift from Takako Sasaki | Unfixed/urea glycine |

| Laminin-α2 | 4H8-2 | Axxora | Unfixed |

| Nephrin | AF3159 | R&D Systems | Unfixed/paraformaldehyde |

| Podocin | P0372 | Sigma | Unfixed |

| Phospho-SMAD2 | AB3849 | EMD Millipore | Paraformaldehyde/ethanol |

| Wilms' tumor-1 | sc-192 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Unfixed |

The number of podocytes is reported as the number of Wilms' tumor-1-positive nuclei per one cross section through the midglomerulus. The extent of tubular injury is expressed as the percentage of kidney injury molecule (KIM)-1-positive/total tubules per kidney section. Apoptosis is reported as the number of TUNEL-positive nuclei per 100 tubules. Macrophage invasion is expressed as the number of CD68-positive cells per millimeter squared. TGF-β signaling was assayed by immunofluorescence staining for phosphorylated (p-)SMAD2. The fluorescent signal was amplified using a Fluorescein tyramide amplification kit (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions and expressed as the number of positive nuclei per tubule and the fluorescence intensity per 100 positive nuclei. All stainings were performed in at least three kidneys from each genotype and were evaluated in three to five fields per kidney.

Statistical Analysis

Except for the survival curve, all data are presented as means ± SD and were analyzed using a two-tailed t-test to determine significance.

RESULTS

Generation and Characterization of Albumin Knockout Mice

To better understand the roles that filtered albumin plays in Alport syndrome, we generated an Alb-null mouse using standard embryonic stem cell methods. The first four exons of the Alb gene, which includes the methionine start codon in exon 1, were replaced by a PGK-neo selectable marker (Fig. 1A). The linearized targeting construct was electroporated into 129X1/SvJ embryonic stem cells. A clone positive for homologous recombination was injected into C57BL/6J (B6) blastocysts, and the resulting high percentage chimeras were bred to B6 mice to generate heterozygous Alb mutant mice. Intercrossing of Alb+/− mice led to the birth of viable Alb−/− mice at the expected Mendelian frequency.

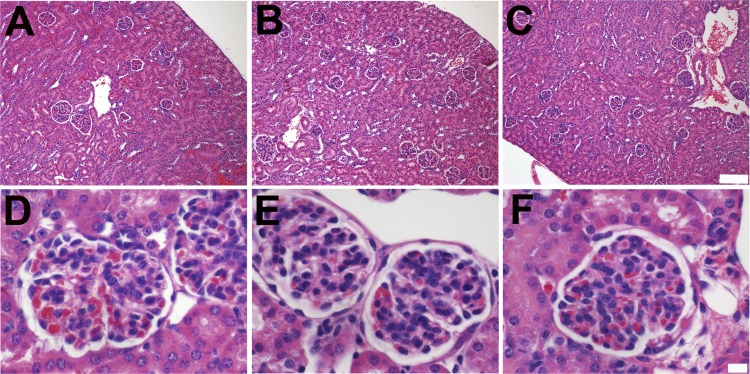

Alb−/− mice appeared normal and were long lived and fertile, with slightly reduced body weights versus Alb+/− and Alb+/+ littermates (data not shown). RT-PCR for albumin mRNA in the liver was negative (Fig. 1B), and, more importantly, there was a complete lack of albumin in the plasma of Alb−/− mice (Fig. 1, C and D). ELISA confirmed the absence of serum albumin in Alb−/− mice and showed a significant reduction in the level of serum albumin in Alb+/− mice (Fig. 1D). Analysis of serum showed hypoproteinemia and hyperlipidemia. At 17 days of age, total serum protein was 39.2 ± 2.2 and 39.6 ± 2.7 g/l in WT and Alb+/− mice, respectively. By comparison, total serum protein concentration was only 28.0 ± 0.1 g/l in Alb−/− mice. In older mice, total serum protein concentration increased to 60.1 ± 0.001 g/l in WT mice, 53.3 ± 3.5 g/l in Alb+/− mice, and 39.4 ± 2.3 g/l in Alb−/− mice. Nonetheless, kidney histology (Fig. 2) and the podocyte ultrastructure (data not shown) were normal. The mean BP of Alb−/− mice (n = 4) on a mixed B6/129 genetic background was 103/72 mmHg, which was within 5 mmHg of control mice on a similar genetic background.

Fig. 2.

Alb−/− and Alb+/− mice have normal kidney histology. A–F: low-magnification (×100; A–C) and high-magnification (×600; D–F) images of hematoxylin and eosin-stained kidney sections from Alb+/+ (A and D), Alb+/− (B and E), and Alb−/− (C and F) mice revealed no obvious histological abnormalities.

Generation of Analbuminemic Alport Mice

To investigate the role of albumin in the progression of Alport syndrome, we bred the Alb mutation onto the C57BL/6J (B6)-Col4a3−/− Alport model background to generate congenic DKO mice.

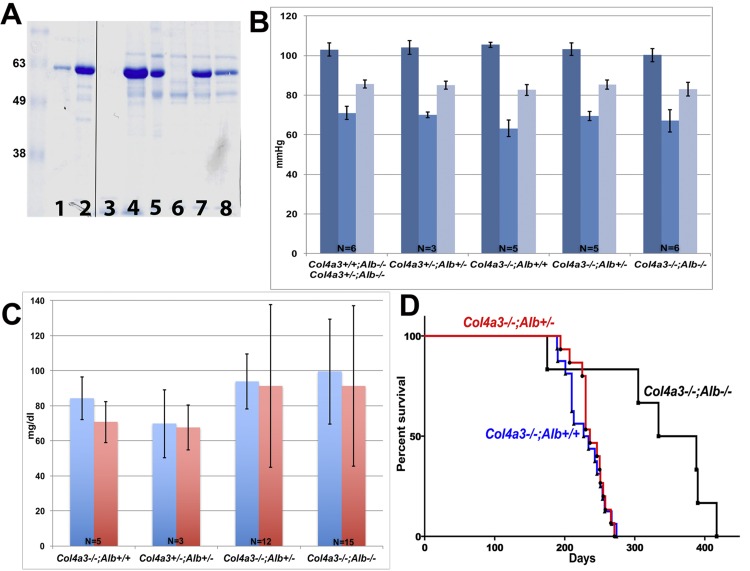

SDS-PAGE analysis confirmed the lack of circulating albumin and albuminuria in DKO mice (Fig. 3A). The lower plasma albumin of Alb+/− mice correlated with reduced albuminuria in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice (Fig. 3A). Considering the importance of albumin in maintaining oncotic pressure and circulatory volume, we measured intravascular BP in anesthetized mice (Fig. 3B). While we found a slightly but significantly higher systolic BP in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/+ mice compared with DKO mice (105.4 vs. 100.2 mmHg, P = 0.01), diastolic BP (63.2 vs. 67.8 mmHg, P = 0.17) and mean arterial BP (82.6 vs. 83 mmHg, P = 0.84) were not different. Systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial BPs were not different between DKO and Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Characterization of collagen-α3(IV)-null (Col4a3−/−);Alb−/− double knockout (DKO) mice. A: SDS-PAGE analysis of 1 and 5 μg BSA (lanes 1 and 2, respectively), 5 μl urine (lanes 3–5), and 0.1 μl serum (lanes 6–8) from a DKO mouse (lanes 3 and 6), a Col4a3−/−;Alb+/+ mouse (lanes 4 and 7), and a Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mouse (lanes 5 and 8); all were 190 days old. Note the complete lack of albumin and albuminuria in the DKO mouse and reduced circulating albumin and albuminuria in the Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mouse. B: intravascular blood pressure (BP) measurements (means ± SD) in the different genotypes, as indicated. Systolic BPs are shown in dark blue, diastolic BPs in light blue, and mean BPs in gray. There were no significant differences between DKO (n = 6) and Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− (n = 5) mice (P values for systolic, diastolic, and mean BPs were 0.15, 0.54 and 0.21, respectively). C: total serum lipid (blue) and triglyceride (red) measurements in adult mice of the different genotypes (means ± SD), as indicated. DKO (n = 15) and Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− (n = 12) mice showed the same level of dyslipidemia (P values for total lipid and triglyceride levels were 0.5 and 0.7, respectively). DKO mice showed a trend toward higher lipid and triglyceride concentrations compared with Col4a3+/−;Alb+/− mice (P values for total lipid and triglyceride levels were 0.12 and 0.13, respectively) and Col4a3−/−;Alb+/+ mice (n = 5), but the differences did not reach statistical significance (P values for total lipid and triglyceride levels were >0.05). D: survival curves for B6 Alport mice WT for albumin (blue line, n = 14), heterozygous for albumin (red line, n = 15), and lacking albumin (black line, n = 6). The mean lifespan of Col4a3−/−;Alb+/+ mice was 220 days. Survival increased to 236 days in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice and to 361 days in DKO mice. The difference in survival was statistically significant between DKO and Alport mice with albumin (P = 0.0015). The difference in survival was not significant between Col4a3−/−;Alb+/+ and Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice (P = 0.76).

Considering the potential role of lipids in kidney diseases (7, 13, 15, 24) and the presence of hyperlipidemia in Alb−/− mice, we measured serum lipid and triglyceride levels in DKO, Col4a3−/−;Alb+/−, and Col4a3−/−;Alb+/+ mice. We found a trend toward higher lipid (mean: 99.5 vs. 84.3 mg/dl) and triglyceride (91.2 vs. 70.7 mg/dl, P = 0.13) concentrations in DKO compared with Col4a3−/−;Alb+/+ mice, although the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.13 for both total lipid and triglyceride levels). Total lipids (99.5 and 93.8 mg/dl) and TG (91.2 and 91.3 mg/dl) were almost identical in DKO and Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice (Fig. 3C).

In initial experiments of mice on a mixed B6/129 strain background, DKO mice were similar to their sex-matched littermates in terms of body weight and kidney-to-body weight ratios (data not shown) before 5 mo of age. DKO mice lived longer than both their Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− littermates and congenic B6 Alport (Col4a3−/−;Alb+/+) mice, which have been reported to be the longest lived (8). This trend continued after backcrossing onto the B6 background to create congenic DKO mice. The median lifespan of B6 Col4a3−/−;Alb+/+ mice was 230 days (Fig. 3D), and Alport Alb+/− mice with reduced albumin lived slightly longer, as their median survival increased to 236 days, although the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.38; Fig. 3D). Survival increased dramatically to 361 days in Alport mice lacking albumin (Fig. 3D), which was significantly longer than Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice (P = 0.021). With the exception of one death at 170 days, all DKO mice lived >300 days. Therefore, the lack of serum albumin and albuminuria increased the life expectancy of Alport mice by 64% (from 230 to 361 days).

Assessing Kidney Disease in the Absence of Albumin

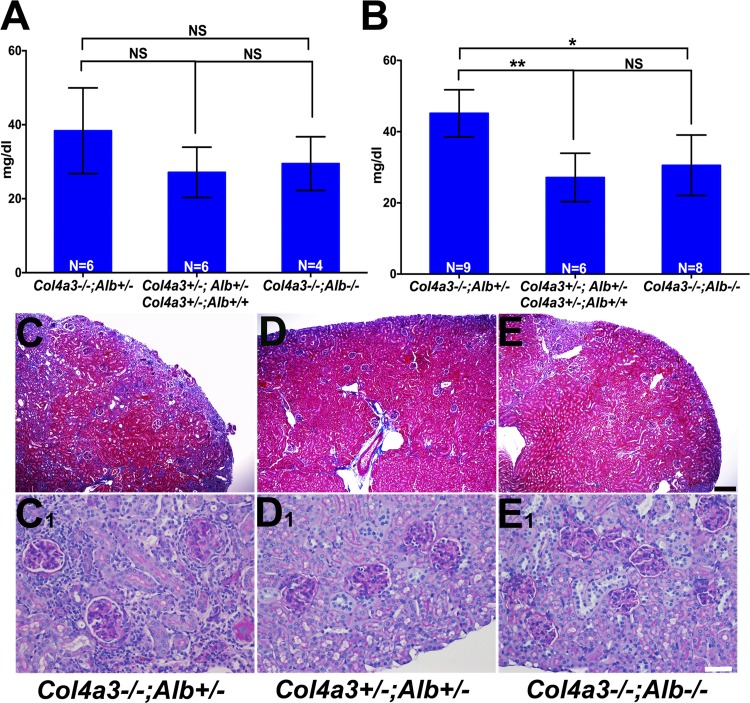

Before 180 days of age, the difference in BUN between DKO mice (mean: 29.5 mg/dl) and Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice (mean: 35.9 mg/dl) was not statistically significant (P = 0.87; Fig. 4A). However, as the mice aged further, BUN rose faster in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice. Between 180 and 255 days of age, mean BUN in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice increased to 45.2 mg/dl, whereas the increase was minimal in DKO mice (29.7 mg/dl); this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.0009; Fig. 4B). No Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− or Col4a3−/−;Alb+/+ mice survived more than 271 days.

Fig. 4.

Characterization of DKO kidney function and histology. A: Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice showed higher blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentrations compared with control (Col4a3+/−;Alb+/− and Col4a3+/−;Alb+/+) and DKO mice before 180 days of age; however, the difference was not statistically significant (NS; P = 0.17 and 0.074, respectively). The difference between control and DKO mice was not significant (NS, P = 0.63). B: after 180 days of age, BUN rose more in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice compared with DKO mice (*P = 0.0017) and compared with control mice (**P = 0.0004). There was no significant change in BUN of DKO mice compared with Col4a3+/−;Alb+/− mice (NS, P = 0.42). The control group was the same in both A and B. C–E: trichrome staining of kidney sections from 200-day-old Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− (C), Col4a3+/−;Alb+/− (D; control), and DKO (E) mice showing reduced fibrosis (blue staining) in DKO kidneys compared with Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− kidneys. Magnification: ×40. Scale bar = 200 μm. C,1–E,1: periodic acid-Schiff staining of kidney sections from 200-day-old Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− (C,1), Col4a3+/−;Alb+/− (D,1), and DKO (E,1) mice showing decreased interstitial fibrosis, inflammation, and glomerulosclerosis in DKO kidneys compared with Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− kidneys. Original magnification was ×200. Scale bar = 50 μm.

To assess whether the change in BUN reflected kidney pathology, we undertook careful histological analysis of kidneys from mice of the different genotypes. This analysis revealed reduced pathology in DKO kidneys versus Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− kidneys of the same age. Regarding glomerular pathology, Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice showed 27.46 ± 2.4% segmentally sclerosed glomeruli and 21.2 ± 3.2% globally sclerosed glomeruli (n = 5). In DKO mice, the number of segmentally sclerotic glomeruli was not significantly different (24.85 ± 2.8%, P = 0.5), but only 5 ± 1.6% of glomeruli were globally sclerosed, which was statistically significant (n = 4, P = 0.0047; Fig. 4, C–E). The average tubulointerstitial injury score in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice after 6 mo of age was moderate to severe, whereas in DKO mice, it was only mild (Fig. 4, C1–E1). Together, these data indicate an overall reduced pathology in DKO mice.

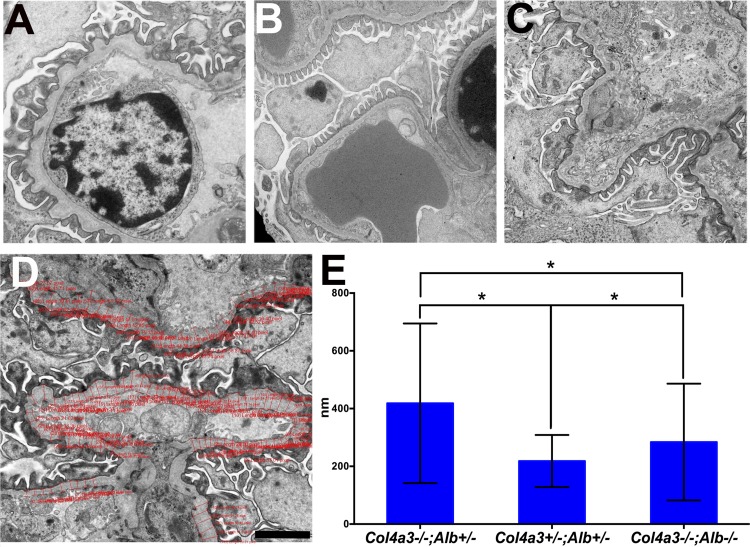

By electron microscopy, the DKO mouse GBM showed the typical splitting and thickening observed in Alport syndrome, but these changes were markedly less severe compared with Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice (Fig. 5, A–D). The mean width of the GBM almost doubled to 418 nm in a Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mouse compared with the GBM of a double heterozygous control (218 nm). While the width of the GBM of the DKO mouse showed a significant increase to 284 nm (P value compared with double heterozygous mice was <0.0001), this was significantly less than the 418-nm Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− GBM (P < 0.0001; Fig. 5E). Moreover, the DKO mice showed reduced podocyte foot process effacement (Fig. 5, A–C).

Fig. 5.

Ultrastructural analysis of the glomerular filtration barrier. A–C: analysis of the glomerular filtration barrier from 200-day-old Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− (A), Col4a3+/−;Alb+/− (B; control), and DKO (C) mice showing preserved glomerular basement membrane (GBM) width and podocyte foot processes in DKO kidneys compared with Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− kidneys (×15,000). D and E: analysis of GBM width. GBM width was measured using Olympus CellSens software as shown in D. Original magnification was ×10,000. Scale bar = 2,000 nm. E: GBM widths in a 200-day-old DKO mouse and a Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mouse compared with a double heterozygous littermate (means ± SD). The numbers of individual measurements were 1,836 for the Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− group, 995 for the Col4a3+/−;Alb+/− group, and 2,298 for the DKO group. *P <0.0001 for all groups.

Despite the improvements in BUN and pathology, DKO mice were not totally protected from injury. As they aged, DKO mice eventually experienced weight loss and a significant increase in BUN to a mean of 37.8 mg/dl after 300 days of age. By the time they became ill, their kidneys displayed all the pathological signs of ESKD. At this stage, tubulointerstitial injury worsened to severe and the number of globally sclerotic glomeruli increased to >30% of total glomeruli (data not shown).

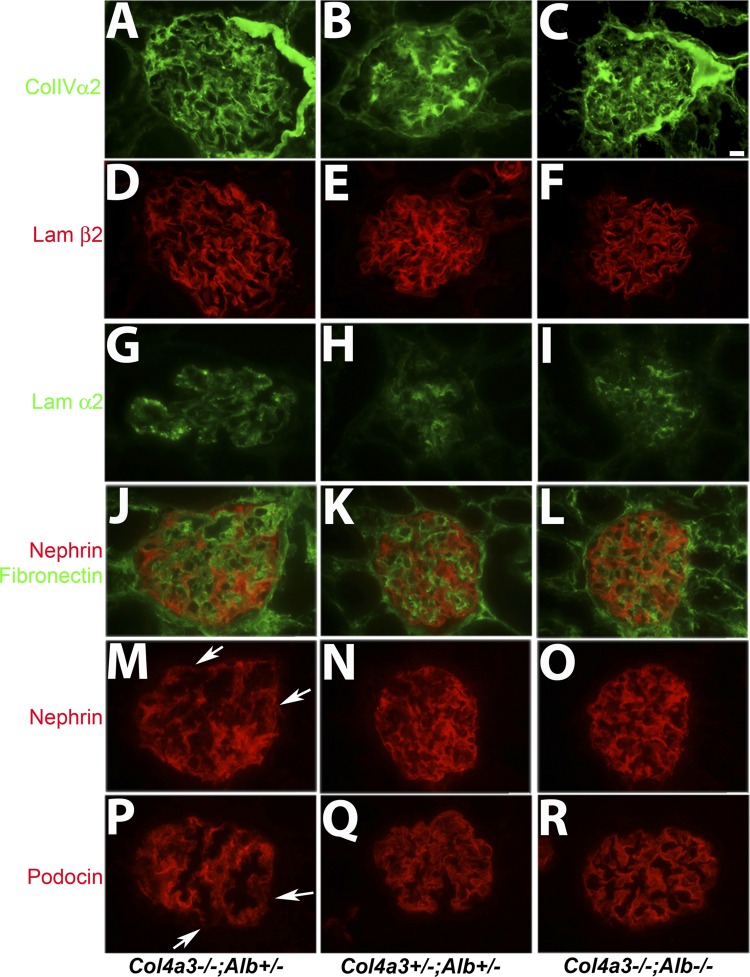

The improvements in glomeruli and kidneys of DKO mice were not related to an increased accumulation of collagen-α5α5α6(IV) in the DKO GBM (data not shown), which is associated with a slower progression to ESKD on the B6 background (3). The major components of the GBM in Col4a3−/−;Alb−/− mice consisted predominantly of collagen-α1α1α2(IV) and laminin-521 (Fig. 6, A–F). Other abnormalities in the GBM were attenuated, especially the deposition of presumably pathogenic laminin-α2 and fibronectin (Fig. 6, G–L). Finally, normal nephrin and podocin expression and localization were preserved longer in DKO mice (Fig. 6, D–R).

Fig. 6.

Characterization of GBM and podocyte proteins in sections from 200-day-old Col4a3−/−;Alb+/−, Col4a3+/−;Alb+/−, and DKO kidneys A–C: collagen-α2(IV) [part of the α1α1α2(IV) trimer] was predominant in the mesangial matrix of Col4a3+/−;Alb+/− glomeruli, with faint signal in the GBM (B). In Alport mice, collagen-α1α1α2(IV) was predominant in the GBM regardless of the presence (A) or absence (C) of albumin. D–F: in normal and Alport glomeruli, the predominant laminin in the GBM was laminin-521, as evidenced by the presence of laminin-β2 in the GBM in all cases. G–I: in normal glomeruli, laminin-α2 was found in the mesangial matrix (H). In Alport glomeruli, increasing amounts of laminin-α2 were deposited into the GBM (G), but this was less so in the absence of albumin (I). J–L: double staining for fibronectin (green) and nephrin (red). In Alport glomeruli (J), fibronectin expanded beyond the mesangial matrix into the GBM, while nephrin localization in podocytes became more diffuse throughout the cell body versus the typical linear signal in normal glomeruli (K). These changes were attenuated in the absence of albumin in DKO mice (L). M–O: nephrin staining from glomeruli shown in J–L. Arrows in M show areas of discontinuous nephrin staining. P–R: podocin localization paralleled that of nephrin. In Alport mice, podocin expression was somewhat reduced and lost its linear staining pattern (P) compared with control (Q). These changes were significantly attenuated in DKO mice (R). Arrows in P show areas of discontinuous podocin staining. Original magnification was ×600 for all images. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Site and Mechanism of Albumin-Induced Injury

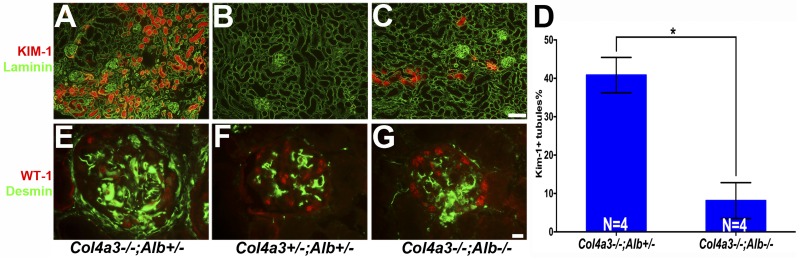

Previous studies have suggested that both PTCs and podocytes are susceptible to albumin-induced injury under overload or proteinuric conditions. Therefore, we investigated the status of some known injury markers in DKO and Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− kidneys.

The presence of albumin was associated with an increase in KIM-1 expression in proximal tubules (Fig. 7, A–D) and increased desmin in glomeruli and podocytes in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− kidneys compared with DKO kidneys (Fig. 7, E–G). Furthermore, at 200 days of age, we detected reduced numbers of Wilms' tumor-1-positive podocyte nuclei in sectioned glomeruli from Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice, on average 8 nuclei/glomerulus versus 12 nuclei/glomerulus in double heterozygous mice and 11.5 nuclei/glomerulus in DKO mice.

Fig. 7.

The absence of albumin improves tubular and glomerular injury. A–D: kidney injury molecule (KIM)-1 (red) showed increased expression in proximal tubules from Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice (A) compared with DKO mice (C). Counterstaining with anti-laminin (green) labeled basement membranes. Original magnification was ×100. Scale bar = 100μm. D: quantification of KIM-1 expression as measured by the percentage of KIM-1-positive tubules. *P <0.0001. KIM-1-positive tubules were very rare in control kidneys (B). Mice were 200 days old. F–H: desmin (green), a marker of mesangial cells, interstitial fibroblasts, and injured podocytes, was increased in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− glomeruli compared with DKO glomeruli. Costaining for Wilms' tumor-1 (WT-1; red nuclei) showed that the number of podocytes was reduced in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice versus the other mice. Original magnification was ×600. Scale bar = 10μm. Mice were 200 days old.

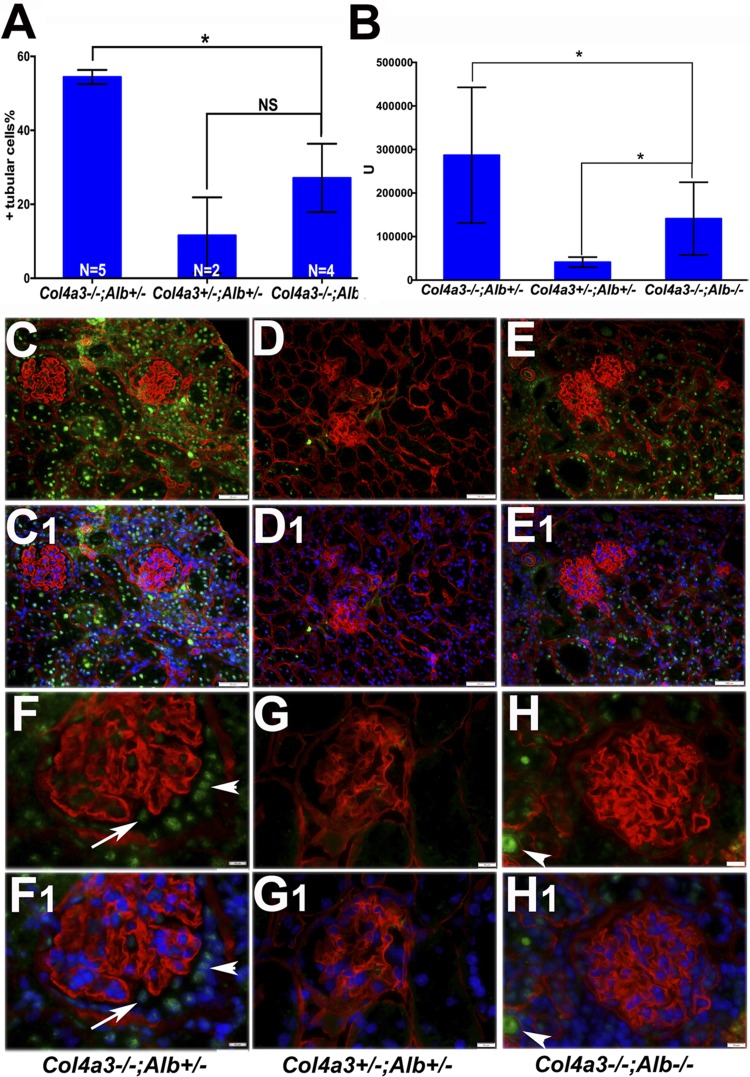

Considering the importance of albumin in the induction of TGF-β1 in PTCs and the central role of TGF-β1 signaling in the fibrosis and inflammation that accompanies Alport syndrome (9, 39), we investigated canonical TGF-β1 signaling in our animal models by assaying for p-SMAD2 and its nuclear localization. We noted an increase in nuclear p-SMAD2 accumulation in PTCs of both Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− and DKO mice compared with normal mice (Fig. 8, A–H). However, the increase in DKO mice was focal compared with that in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice, which was more widespread and more intense by comparison (Fig. 8, A and B). Furthermore, we also noted increased nuclear p-SMAD2 in podocytes and parietal epithelial cells of Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice versus DKO and control mice (Fig. 8, F–H). Activation of TGF-β1 signaling was associated with increased tubulointerstitial injury, fibrosis, and inflammation, as evidenced by increased numbers of invading macrophages (Fig. 9), apoptotic cells (Fig. 10), α-smooth muscle actin-positive myofibroblasts (data not shown) as well as increased interstitial collagen deposition, as demonstrated by trichrome staining (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 8.

The absence of albumin attenuated transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 signaling as assayed by nuclear phosphorylated (p-)SMAD2. Nuclear p-SMAD2 was detected by immunofluorescence in sections of 180- to 220-day-old Col4a3−/−;Alb+/−, Col4a3+/−;Alb+/−, and DKO kidneys. A and B: quantification of p-SMAD2 staining in tubular cells. A: percentage of p-SMAD2-positive tubular nuclei. Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− kidneys showed a significant increase in p-SMAD2-positive tubular cells compared with DKO kidneys. *P = 0.0085. The difference between DKO and control kidneys was not significant (NS, P = 0.22). B: mean fluorescence intensity of 100 positive nuclei. *P < 0.0001 for all groups. C–E: examples of p-SMAD2 nuclear localization in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− kidneys (C) compared with control (D) and DKO (E) kidneys. Counterstaining with anti-nidogen (red) labeled all basement membranes. C1–E1: nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 to confirm p-SMAD2 nuclear localization. Original magnification was ×100. Scale bar = 100 μm. F–H: higher-magnification images showing nuclear p-SMAD2 distribution in glomeruli from 200-day-old mice. F1–H1: nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 to confirm p-SMAD2 nuclear localization. Arrowhead and arrow point to parietal epithelial cells with increased nuclear p-SMAD2 staining and a podocyte with nuclear p-SMAD2, respectively, in a Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− kidney. There was no detectable nuclear p-SMAD2 staining in control (G) or DKO (H) glomeruli. Arrowheads in H and H1 indicate background staining of a tubular cast. Original magnification was ×600. Scale bar = 10 μm.

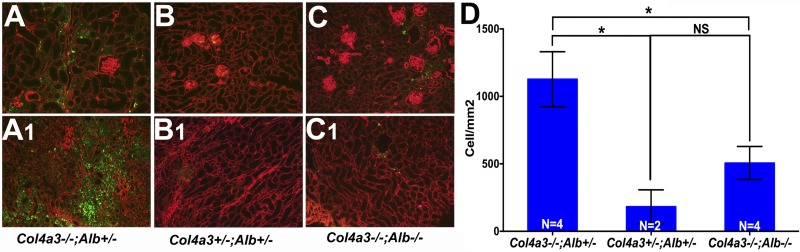

Fig. 9.

Absence of albumin decreased macrophage infiltration in Alport kidneys. Kidneys from Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice (A and A1) showed extensive macrophage infiltration, as evidenced by extensive CD68 staining (green) in the cortex (A) and medulla (A,1). DKO kidneys (C and C1) showed a reduction in macrophage invasion that was similar to control kidneys (B and B1). Counterstaining with laminin-α5 antibody (red) labeled all basement membranes. Original magnification was ×100. Scale bar = 100 μm. Mice were 200 days old. D: quantification of macrophage infiltration as measured by the number of CD68-positive cells/mm2. The difference was significant between Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− kidneys and kidneys from DKO and control mice (*P = 0.0036 and 0.0039, respectively). The difference between DKO and control kidneys was not significant (NS, P = 0.093).

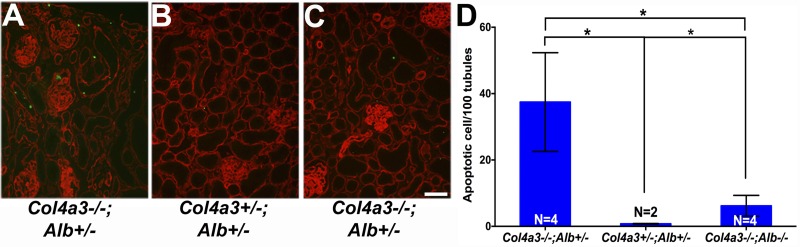

Fig. 10.

Absence of albumin decreased tubular cell apoptosis in DKO kidneys. TUNEL staining (green) identified increased numbers of apoptotic cells in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− kidneys (A) compared with DKO kidneys (C). In control kidneys (B), there were only occasional (<1 cell/high-power field) apoptotic cells within the interstitium. Counterstaining with anti-nidogen (red) labeled all basement membranes. Original magnification was ×200. Scale bar = 50 μm. D: quantification of tubular cell apoptosis as measured by the number of TUNEL-positive nuclei per 100 tubules. The difference between Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− kidneys and kidneys from DKO and control mice was significant (*P = 0.022 and 0.016, respectively). There were significantly more apoptotic tubular cells in DKO kidneys compared with control kidneys (*P = 0.016).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we attempted to determine whether filtered albumin might be a contributor to kidney disease progression in Alport syndrome. To isolate the contribution of albumin from other confounding factors, we generated albumin-deficient mice. Alb−/− mice were phenotypically normal as expected, given the human and rat data, with the exception of complete lack of albumin, decreased total serum protein, and dyslipidemia. Once we generated DKO mice, it was clear that their kidney disease was less severe compared with Alport mice with normal albumin (Alb+/+) or with ∼50% reduced serum albumin (Alb+/−).

Perhaps surprisingly, the improvement in kidney disease outcomes did not parallel the absolute levels of reduction in albumin and albuminuria. Although the lifespan of Alport mice with a heterozygous albumin mutation improved, this improvement was negligible compared with the improvement observed in DKO mice. At this time, it is unclear whether this discrepancy is related to the small differences in serum lipid levels and BP between Alport mice with normal albumin and mice with reduced albumin. Alternatively, the reduction in albuminuria in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice might not be sufficient to attenuate the negative effects of albumin overload distal to the glomerular filtration barrier.

Although DKO mice showed slightly lower BPs compared with Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice, the 3-mmHg difference was not statistically significant and is unlikely to be the cause of better outcome. We did not measured intraglomerular pressure in our mice due to technical limitations, but although NARs have lower glomerular pressures at baseline, they are nevertheless more susceptible to developing glomerular hypertension upon induction of kidney injury. Therefore, any differences in glomerular pressure are unlikely to contribute to the improved outcomes in our DKO mice. Moreover, although DKO mice developed hypertriglyceridemia, similar changes were also noted in Col4a3−/−;Alb+/− mice, which showed a more rapid progression to ESKD. Therefore, we conclude that the lack of albumin per se, rather than the secondary effect on serum lipids, is the cause of improved outcomes in DKO mice.

Especially interesting is that fact that the harmful effects of albumin extended beyond PTCs to the glomerulus and podocytes. Our results suggest that the higher albumin concentrations in the primary glomerular filtrate and in the tubular lumen that should occur relatively early in Alport syndrome (3) increase exposure of both podocytes and PTCs to albumin and activates the TGF-β signaling pathway, which is well known to contribute to propagating kidney injury in Alport mice. Albumin-induced upregulation of TGF-β1 might be central not only to the development of tubulointerstitial disease but also for glomerular pathology, especially in regard to increasing GBM width, as recently shown in diabetic nephropathy (21).

It is notable that although the absence of albumin resulted in a significantly slower progression to ESKD in Alport mice, analbuminemia did not rescue the kidney phenotype, as the mice still eventually reached ESKD after 1 yr; therefore, albumin is only one of the factors that leads to progressive kidney injury.

While we were able to show the importance of albumin in the pathogenesis of Alport syndrome, there are multiple unresolved questions that will require further investigations: 1) the mechanism of injury induced by albumin; 2) whether albumin plays the same role in other proteinuric kidney diseases, especially diabetic nephropathy; 3) whether the role of albumin will depend on the primary cause of proteinuria; and 4) whether we can explain the apparent lack of albumin toxicity in minimal change disease by its different pathogenesis compared with Alport syndrome. Furthermore, whereas the congenital lack of albumin is well tolerated even in the setting of kidney disease, depletion of albumin after birth as a therapy is not practical and would likely be harmful. However, by understanding the nature of albumin-induced injury mechanistically, we hope to be able to improve the outcome of proteinuric kidney disease by therapeutically antagonizing the harmful effects of albumin.

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

While this manuscript was in process, we became aware of another Alb knockout mouse reported here: Roopenian DC, Low BE, Christianson GJ, Proetzel G, Sproule TJ, Wiles MV. Albumin-deficient mouse models for studying metabolism of human albumin and pharmacokinetics of albumin-based drugs. mAbs 7:344–351, 2015.

GRANTS

This work was supported by an American Society of Nephrology/Alaska Kidney Foundation Research Grant (to G. Jarad), American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid 14GRNT20370035 (to J. H. Miner), and by NIH Grants P30DK079333 (Pilot and Feasibility Study to G. Jarad), R56DK100593 (to G. Jarad and J. H. Miner), R01DK078314 (to J. H. Miner), and R01HL105314 (to R. P. Mecham).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

G.J., R.P.M., and J.H.M. conception and design of research; G.J., R.H.K., and J.H.M. performed experiments; G.J., R.H.K., R.P.M., and J.H.M. analyzed data; G.J., R.H.K., R.P.M., and J.H.M. interpreted results of experiments; G.J. prepared figures; G.J. and J.H.M. drafted manuscript; G.J., R.H.K., R.P.M., and J.H.M. edited and revised manuscript; G.J. and J.H.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Yoshikazu Sado and Takako Sasaki for gifts of antibodies; Jeanette Cunningham, Jennifer Richardson, and Gloriosa Go for technical assistance; the Washington University Embryonic Stem Cell and Mouse Genetics Cores, the Washington University Center for Kidney Disease Research [National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant P30DK079333] and Diabetes Research Center (NIH Grant P30DK020579) for the generation of knockout mice; the Digestive Diseases Research Core Center (NIH Grant P30DK052574) for histology; and the Nutrition Obesity Research Center (NIH Grant P30DK056341) for measuring serum lipids. Mice were housed in a facility supported by NIH Grant C06RR015502.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbate M, Zoja C, Morigi M, Rottoli D, Angioletti S, Tomasoni S, Zanchi C, Longaretti L, Donadelli R, Remuzzi G. Transforming growth factor-β1 is up-regulated by podocytes in response to excess intraglomerular passage of proteins: a central pathway in progressive glomerulosclerosis. Am J Pathol 161: 2179–2193, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abe H, Shibuya T, Odashima S, Arichi S, Nagase S. Alterations in the glomerulus in aminonucleoside nephrosis in analbuminemic rats. Nephron 50: 351–355, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrahamson DR, Isom K, Roach E, Stroganova L, Zelenchuk A, Miner JH, St John PL. Laminin compensation in collagen α3(IV) knockout (Alport) glomeruli contributes to permeability defects. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2465–2472, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrews KL, Mudd JL, Li C, Miner JH. Quantitative trait loci influence renal disease progression in a mouse model of Alport syndrome. Am J Pathol 160: 721–730, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennhold H, Kallee E. Comparative studies on the half-life of I131-labeled albumins and nonradioactive human serum albumin in a case of analbuminemia. J Clin Invest 38: 863–872, 1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buelli S, Abbate M, Morigi M, Moioli D, Zanchi C, Noris M, Zoja C, Pusey CD, Zipfel PF, Remuzzi G. Protein load impairs factor H binding promoting complement-dependent dysfunction of proximal tubular cells. Kidney Int 75: 1050–1059, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung JJ, Huber TB, Godel M, Jarad G, Hartleben B, Kwoh C, Keil A, Karpitskiy A, Hu J, Huh CJ, Cella M, Gross RW, Miner JH, Shaw AS. Albumin-associated free fatty acids induce macropinocytosis in podocytes. J Clin Invest 125: 2307–2316, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cosgrove D, Kalluri R, Miner JH, Segal Y, Borza DB. Choosing a mouse model to study the molecular pathobiology of Alport glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 71: 615–618, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosgrove D, Rodgers K, Meehan D, Miller C, Bovard K, Gilroy A, Gardner H, Kotelianski V, Gotwals P, Amatucci A, Kalluri R. Integrin α1β1 and transforming growth factor-β1 play distinct roles in Alport glomerular pathogenesis and serve as dual targets for metabolic therapy. Am J Pathol 157: 1649–1659, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cybulsky AV. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in proteinuric kidney disease. Kidney Int 77: 187–193, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cybulsky AV. The intersecting roles of endoplasmic reticulum stress, ubiquitin- proteasome system, and autophagy in the pathogenesis of proteinuric kidney disease. Kidney Int 84: 25–33, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies DJ, Messina A, Thumwood CM, Ryan GB. Glomerular podocytic injury in protein overload proteinuria. Pathology 17: 412–419, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deji N, Kume S, Araki S, Soumura M, Sugimoto T, Isshiki K, Chin-Kanasaki M, Sakaguchi M, Koya D, Haneda M, Kashiwagi A, Uzu T. Structural and functional changes in the kidneys of high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F118–F126, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diwakar R, Pearson AL, Colville-Nash P, Brunskill NJ, Dockrell ME. The role played by endocytosis in albumin-induced secretion of TGF-β1 by proximal tubular epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F1464–F1470, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eller P, Eller K, Wolf AM, Reinstadler SJ, Tagwerker A, Patsch JR, Mayer G, Rosenkranz AR. Atorvastatin attenuates murine anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 77: 428–435, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang L, Xie D, Wu X, Cao H, Su W, Yang J. Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress in albuminuria induced inflammasome activation in renal proximal tubular cells. PLos One 8: e72344, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujihara CK, Limongi DM, De Oliveira HC, Zatz R. Absence of focal glomerulosclerosis in aging analbuminemic rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 262: R947–R954, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujihara CK, Limongi DM, Falzone R, Graudenz MS, Zatz R. Pathogenesis of glomerular sclerosis in subtotally nephrectomized analbuminemic rats. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 261: F256–F264, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross O, Beirowski B, Koepke ML, Kuck J, Reiner M, Addicks K, Smyth N, Schulze-Lohoff E, Weber M. Preemptive ramipril therapy delays renal failure and reduces renal fibrosis in COL4A3-knockout mice with Alport syndrome. Kidney Int 63: 438–446, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gross O, Licht C, Anders HJ, Hoppe B, Beck B, Tonshoff B, Hocker B, Wygoda S, Ehrich JH, Pape L, Konrad M, Rascher W, Dotsch J, Muller-Wiefel DE, Hoyer P, Knebelmann B, Pirson Y, Grunfeld JP, Niaudet P, Cochat P, Heidet L, Lebbah S, Torra R, Friede T, Lange K, Muller GA, Weber M. Early angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in Alport syndrome delays renal failure and improves life expectancy. Kidney Int 81: 494–501, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hathaway CK, Gasim AM, Grant R, Chang AS, Kim HS, Madden VJ, Bagnell CR Jr, Jennette JC, Smithies O, Kakoki M. Low TGFβ1 expression prevents and high expression exacerbates diabetic nephropathy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 5815–5820, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishola DA Jr, Post JA, van Timmeren MM, Bakker SJ, Goldschmeding R, Koomans HA, Braam B, Joles JA. Albumin-bound fatty acids induce mitochondrial oxidant stress and impair antioxidant responses in proximal tubular cells. Kidney Int 70: 724–731, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarad G, Cunningham J, Shaw AS, Miner JH. Proteinuria precedes podocyte abnormalities in Lamb2−/− mice, implicating the glomerular basement membrane as an albumin barrier. J Clin Invest 116: 2272–2279, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang T, Wang Z, Proctor G, Moskowitz S, Liebman SE, Rogers T, Lucia MS, Li J, Levi M. Diet-induced obesity in C57BL/6J mice causes increased renal lipid accumulation and glomerulosclerosis via a sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 280: 32317–32325, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kashtan CE, Ding J, Gregory M, Gross O, Heidet L, Knebelmann B, Rheault M, Licht C. Clinical practice recommendations for the treatment of Alport syndrome: a statement of the Alport Syndrome Research Collaborative. Pediatr Nephrol 28: 5–11, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koot BG, Houwen R, Pot DJ, Nauta J. Congenital analbuminaemia: biochemical and clinical implications. A case report and literature review. Eur J Pediatr 163: 664–670, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemley KV, Kriz W. Glomerular injury in analbuminemic rats after subtotal nephrectomy. Nephron 59: 104–110, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miner JH, Go G, Cunningham J, Patton BL, Jarad G. Transgenic isolation of skeletal muscle and kidney defects in laminin beta2 mutant mice: implications for Pierson syndrome. Development 133: 967–975, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miner JH, Patton BL, Lentz SI, Gilbert DJ, Snider WD, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Sanes JR. The laminin alpha chains: expression, developmental transitions, and chromosomal locations of α1–5, identification of heterotrimeric laminins 8–11, and cloning of a novel α3 isoform. J Cell Biol 137: 685–701, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miner JH, Sanes JR. Molecular and functional defects in kidneys of mice lacking collagen α3(IV): implications for Alport syndrome. J Cell Biol 135: 1403–1413, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morigi M, Buelli S, Angioletti S, Zanchi C, Longaretti L, Zoja C, Galbusera M, Gastoldi S, Mundel P, Remuzzi G, Benigni A. In response to protein load podocytes reorganize cytoskeleton and modulate endothelin-1 gene: implication for permselective dysfunction of chronic nephropathies. Am J Pathol 166: 1309–1320, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagase S, Shimamune K, Shumiya S. Albumin-deficient rat mutant. Science 205: 590–591, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neuhaus TJ, Stallmach T, Genewein A. A boy with congenital analbuminemia and steroid-sensitive idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: an experiment of nature. Eur J Pediatr 167: 1073–1077, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohse T, Inagi R, Tanaka T, Ota T, Miyata T, Kojima I, Ingelfinger JR, Ogawa S, Fujita T, Nangaku M. Albumin induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in renal proximal tubular cells. Kidney Int 70: 1447–1455, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okamura K, Dummer P, Kopp J, Qiu L, Levi M, Faubel S, Blaine J. Endocytosis of albumin by podocytes elicits an inflammatory response and induces apoptotic cell death. PLos One 8: e54817, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okuda S, Oochi N, Wakisaka M, Kanai H, Tamaki K, Nagase S, Onoyama K, Fujishima M. Albuminuria is not an aggravating factor in experimental focal glomerulosclerosis and hyalinosis. J Lab Clin Med 119: 245–253, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peired A, Angelotti ML, Ronconi E, la Marca G, Mazzinghi B, Sisti A, Lombardi D, Giocaliere E, Della Bona M, Villanelli F, Parente E, Ballerini L, Sagrinati C, Wanner N, Huber TB, Liapis H, Lazzeri E, Lasagni L, Romagnani P. Proteinuria impairs podocyte regeneration by sequestering retinoic acid. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1756–1768, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reich H, Tritchler D, Herzenberg AM, Kassiri Z, Zhou X, Gao W, Scholey JW. Albumin activates ERK via EGF receptor in human renal epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1266–1278, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sayers R, Kalluri R, Rodgers KD, Shield CF, Meehan DT, Cosgrove D. Role for transforming growth factor-β1 in Alport renal disease progression. Kidney Int 56: 1662–1673, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shalamanova L, McArdle F, Amara AB, Jackson MJ, Rustom R. Albumin overload induces adaptive responses in human proximal tubular cells through oxidative stress but not via angiotensin II type 1 receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F1846–F1857, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagenseil JE, Knutsen RH, Li DY, Mecham RP. Elastin-insufficient mice show normal cardiovascular remodeling in 2K1C hypertension despite higher baseline pressure and unique cardiovascular architecture. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H574–H582, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshida S, Nagase M, Shibata S, Fujita T. Podocyte injury induced by albumin overload in vivo and in vitro: involvement of TGF-β and p38 MAPK. Nephron Exp Nephrol 108: e57–68, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao J, Tramontano A, Makker SP. Albumin-stimulated TGFβ-1 in renal tubular cells is associated with activation of MAP kinase. Int Urol Nephrol 39: 1265–1271, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou LL, Hou FF, Wang GB, Yang F, Xie D, Wang YP, Tian JW. Accumulation of advanced oxidation protein products induces podocyte apoptosis and deletion through NADPH-dependent mechanisms. Kidney Int 76: 1148–1160, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]