The study provides evidence of a selective downregulation of mitochondrial electron transport chain functional activity predominantly affecting complexes I and II and associated increase in oxidative stress in atrial tissue from patients with atrial fibrillation in a well-matched group of patients with respect to comorbidities and well-preserved left ventricular function undergoing open-heart surgery.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, humans, mitochondria, electron transport chain complexes, oxidative phosphorylation, oxidative stress, superoxide, 4-hydroxynonenal protein adducts

Abstract

Mitochondria are critical for maintaining normal cardiac function, and a deficit in mitochondrial energetics can lead to the development of the substrate that promotes atrial fibrillation (AF) and its progression. However, the link between mitochondrial dysfunction and AF in humans is still not fully defined. The aim of this study was to elucidate differences in the functional activity of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes and oxidative stress in right atrial tissue from patients without (non-AF) and with AF (AF) who were undergoing open-heart surgery and were not significantly different for age, sex, major comorbidities, and medications. The overall functional activity of the electron transport chain (ETC), NADH:O2 oxidoreductase activity, was reduced by 30% in atrial tissue from AF compared with non-AF patients. This was predominantly due to a selective reduction in complex I (0.06 ± 0.007 vs. 0.09 ± 0.006 nmol·min−1·citrate synthase activity−1, P = 0.02) and II (0.11 ± 0.012 vs. 0.16 ± 0.012 nmol·min−1·citrate synthase activity−1, P = 0.003) functional activity in AF patients. Conversely, complex V activity was significantly increased in AF patients (0.21 ± 0.027 vs. 0.12 ± 0.01 nmol·min−1·citrate synthase activity−1, P = 0.005). In addition, AF patients exhibited a higher oxidative stress with increased production of mitochondrial superoxide (73 ± 17 vs. 11 ± 2 arbitrary units, P = 0.03) and 4-hydroxynonenal level (77.64 ± 30.2 vs. 9.83 ± 2.83 ng·mg−1 protein, P = 0.048). Our findings suggest that AF is associated with selective downregulation of ETC activity and increased oxidative stress that can contribute to the progression of the substrate for AF.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

The study provides evidence of a selective downregulation of mitochondrial electron transport chain functional activity predominantly affecting complexes I and II and associated increase in oxidative stress in atrial tissue from patients with atrial fibrillation in a well-matched group of patients with respect to comorbidities and well-preserved left ventricular function undergoing open-heart surgery.

atrial fibrillation (AF), a rapid irregular rhythm of the atria, is associated with electrical, functional, and structural changes in the atria that promote the substrate for its recurrence and progression (36, 53, 60). The incidence and prevalence of AF increase with advancing age and aging-associated diseases such as hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and heart failure (2, 40) and contribute to increased morbidity, particularly an increased risk for stroke, heart failure, and death (25, 52). Although the pathophysiology of AF has been well characterized, the underlying mechanisms that contribute to the progression of AF in human atria have not been fully defined (33, 35, 57, 58, 60). Mitochondria, occupying 30% of cardiomyocyte volume, are critical for maintaining normal energetics of the heart, a highly aerobic organ dependent on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) for maintenance of its normal electrical and mechanical function (1, 61). Imbalance in the production of high-energy phosphate compounds and metabolic oscillations with supply-demand mismatch in adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) can affect cardiac electrical activity through impact on ion channels (5a, 11, 15, 27), oxidative stress, and regulation of cell death/survival signaling (12, 17, 56, 59), which increases predisposition to arrhythmogenesis. However, information pertaining to derangement in the OXPHOS in human AF compared with a well-matched group without AF is lacking. This is important because conditions that predispose to AF—such as aging, hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, or ventricular or atrial dysfunction—can by themselves contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction and must be accounted for when estimating the impact of AF on mitochondrial function (5, 11, 15, 17). Moreover, it is not clear whether reported changes in myocardial energetics and mitochondrial function (1, 27, 56) are causative or the consequence of AF or associated conditions; nor is it clear whether the OXPHOS impairment reported in some (32) but not all (5a) animal studies also occurs in the human atria (12, 37, 50). Increasing evidence has accumulated that oxidative stress plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AF (47, 17, 62) and elevated oxidative stress markers are present in patients with AF (34, 41, 43, 51). Oxidative stress can result from mitochondrial dysfunction with impairment in electron transport chain (ETC) activity (17), but this has not been systematically assessed in human atria.

The purpose of this study was therefore to assess the functional activity of the mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes I–V, expression level of their representative protein subunits, and oxidative stress, in patients with AF and comorbidity-matched patients without AF undergoing open-heart surgery.

METHODS

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics.

Middle-aged and elderly patients with or without a history of AF undergoing elective open-heart surgery between July 2012 and February 2016 at Aurora St. Luke's Medical Center in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, gave informed consent, and their atrial appendage tissues were used for this study. Patients undergoing emergency bypass surgery, requiring inotropic support, and with congenital heart disease, New York Heart Association class III and IV heart failure, systemic disorders such as infection, or severe left ventricular (LV) dysfunction (LV ejection fraction <35%) were excluded. Patients who had had prior cardiac surgery or an ablation procedure for AF management also were excluded. Patients with no history of AF were classified as the non-AF group and those with documentation of sustained AF as the AF group (25). The study was approved by the Aurora Institutional Review Board and adhered to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and Aurora Health Care patient privacy and security guidelines. The study conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Processing of atrial samples.

After removal from patients, the right atrial appendage tissue was immediately transferred into ice-cold Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS). Fat and connective tissue were trimmed off, and the muscle tissue was used fresh for fiber isolation or cut into pieces and frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C for OXPHOS functional analysis, 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) protein adducts, and proteomic assessment. Less than 5 min elapsed between removal of the tissue from the patient and freezing. If any delay occurred in collection or storage, the tissue was not used for the study.

Preparation of atrial homogenate.

For functional assessment, the frozen tissue sample (∼50 mg) was transferred into an ice-cold buffer (1:20 wt/vol) containing (in mM) 100 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 2 EGTA, and 50 Tris·HCl (pH 7.5) and homogenized with an OMNI Polytron homogenizer (OMNI International, Kennesaw, GA) at setting 6 on ice, as previously described, with minor modifications (55). The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000 g for 15 min at 4°C; the supernatant was filtered through a polypropylene mesh with open size 0.125 mm, divided into aliquots, and stored at −80°C until being processed.

Polarographic measurements of NADH:O2 oxidoreductase activity.

Rotenone-sensitive NADH:O2 oxidoreductase activity was measured in tissue homogenates with a Clarke oxygen electrode at 30°C in medium containing (in mM) 120 KCl, 2 KH2PO4, 1 EGTA, 10 Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), and 0.1 cytochrome c (Cyt c). To define the maximum activity of NADH:O2 oxidoreductase, 100 μM β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, reduced form (NADH) was added and rotenone-sensitive activity was quantified after addition of 4 μM rotenone. The rate of NADH:O2 oxidoreductase activity was normalized to mitochondrion-specific protein citrate synthase (CS) activity and expressed as nanograms of atoms of O2 per minute per CS activity.

Assessment of mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes.

The functional activity of individual OXPHOS complexes (Fig. 1) was analyzed spectrophotometrically (46) with the Infinite 200 PRO Plate Reader microplate reader (Tecan US, Research Triangle Park, NC) at 30°C. The activity was calculated as previously described (9) and normalized to CS activity.

Fig. 1.

Measurement of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complex activity. Complex I activity was measured using exogenous β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, reduced form (NADH) as donor and 2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-6-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)-1,4-benzoquinone (Q1) as acceptor of electrons; rotenone (Rot) was added to quantify rotenone-sensitive NADH-decylubiquinone oxidoreductase activity. Complex II activity was determined using succinate as donor and 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) as acceptor; succinate-decylubiquinone 2,6-dichlorphenolindophenol reductase activity was determined in the presence of 2-thenoyl-trifluoroacetone (TTFA). Complex III activity was measured using decylubiquinol (DBH2) as donor and the oxidized form of cytochrome c (Cyt c) as acceptor; antimycin A (AA) was used to distinguish the reduction of Cyt c catalyzed by the ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase from the nonenzymatic reduction of Cyt c. Complex IV activity was estimated by using the reduced form of Cyt c (red Cyt c) as the electron donor for oxygen. Complex V activity was measured by coupled reactions using lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and pyruvate kinase (PK) as the coupling enzymes; oligomycin A (Oligom) was added to determine the oligomycin-sensitive ATPase activity. The wavelength of absorbance is summarized for each complex. NAD+, oxidized form of β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; ATP, adenosine 5′-triphosphate; ADP, adenosine 5′-diphosphate; Pi, inorganic phosphate; Q, endogenous ubiquinone; CI–CV, mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes.

The activity of complex I (NADH-decylubiquinone oxidoreductase) was measured from decreased absorbance of NADH in incubation medium containing 10 mM KH2PO4 (pH 8.0) supplemented with 50 μM 2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-6-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)-1,4-benzoquinone (Q1) as an electron acceptor, 100 μM NADH as an electron donor, and 2 μM antimycin A to block the activity of downstream complexes. The addition of 4 μM rotenone allowed quantification of the rotenone-sensitive activity of the enzyme (Fig. 1). The extinction coefficient 6.81 mM−1·cm−1 for NADH at 340 nm was used to quantify the functional activity. The activity of complex II (succinate-decylubiquinone 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol reductase) was measured in an incubation media containing 50 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.4) supplemented with 10 mM succinate as a donor, 50 μM 2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-6-geranyl-1,4-benzoquinone (Q2), and 75 μM 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) as an acceptor of electrons, in the presence of 4 μM rotenone and 2 μM antimycin A (Fig. 1). Baseline activity of complex II was determined with 5 mM 2-thenoyl-trifluoroacetone (TTFA), a selective inhibitor of succinate dehydrogenase. The extinction coefficient 21 mM−1·cm−1 for DCPIP at 600 nm was used to quantify the functional activity of the complex. Complex III (ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase) activity was determined in an incubation buffer containing (in mM) 10 KH2PO4 (pH 7.4), 1 EDTA, and 1 sodium azide in the presence of 100 μM oxidized Cyt c as an electron acceptor and 50 μM decylubiquinol (DBH2) as a donor. Decylubiquinone was reduced to decylubiquinol according to the method of Trounce et al. (54) with minor modifications. To 150 μl of 2.6 mM decylubiquinone 2 mg sodium borohydride was added. Then DBH2 solution was stabilized with 50 μl of 1 N HCl. To distinguish the reduction of Cyt c catalyzed by the complex III and the nonenzymatic reduction of Cyt c by the reduced quinone, 2 μM antimycin A was used. The extinction coefficient of reduced Cyt c was taken as 20 mM−1·cm−1 at 550 nm to quantify the functional activity of the complex. The activity of complex IV (cytochrome-c oxidase) activity was measured with a cytochrome-c oxidase assay kit, CYTOCOX1, from the decrease in absorbance at 550 nm of ferrocytochrome c (reduced Cyt c) caused by its oxidation to ferricytochrome c by cytochrome-c oxidase as described in the kit.

Complex V (oligomycin-sensitive ATPase) activity was measured by coupled assays using pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase reactions after oxidation of NADH at 340 nm in medium containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 5 mM MgSO4, 4 μM rotenone, 5 mM phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), 5 μg/ml pyruvate kinase, 5 μg/ml lactate dehydrogenase, 0.4 mM NADH, and 2.5 mM ATP. Oligomycin A (5 μg/ml) was added to determine oligomycin A-sensitive ATPase activity. The extinction coefficient 6.22 mM−1·cm−1 for NADH at 340 nm was used to quantify the functional activity.

Citrate synthase activity.

The activity of CS in atrial homogenate was measured in medium containing (in mM) 100 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 2 EGTA, and 50 Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), as previously described (24). Reaction medium was supplemented with 10 mM 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid), 30 mM acetyl-CoA, and 10 mM oxaloacetic acid. The extinction coefficient for 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoic acid (TNB) was 13.6 mM−1·cm−1 at 412 nm. The CS functional activity was expressed as nanomoles of TNB per minute per milligram of noncollagen protein (NCP) (10) and used for normalization of the OXPHOS complex activity.

Noncollagen protein determination.

The NCP was determined by a BCA protein assay kit using protein extraction obtained from tissue homogenates with 0.1 M NaOH as previously described (55). After solubilization of the homogenate (10 min), the extract was centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 min to precipitate NaOH-insoluble collagen protein. The NCP concentration was determined as milligrams of protein per milliliter of homogenate. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a standard.

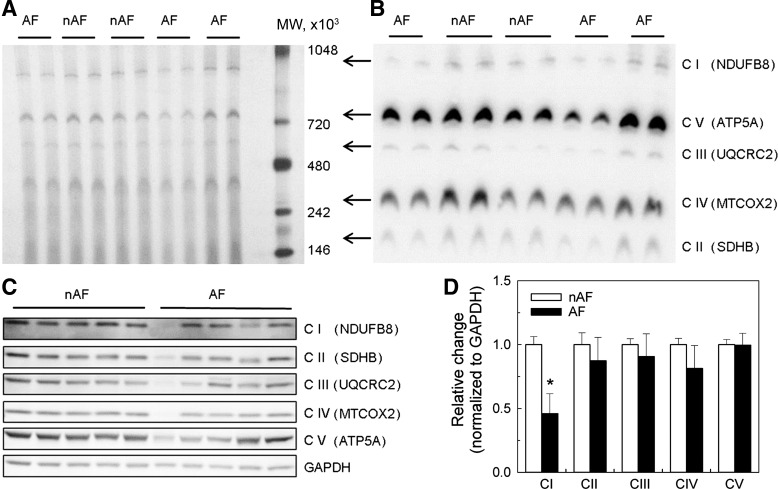

Separation and identification of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes by 1D BN-PAGE and Western blot.

One-dimensional blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (1D BN-PAGE) was performed by Kendrick Laboratories (Madison, WI). Briefly, frozen atrial samples (10–50 mg) were homogenized in an ice-cold buffer containing (in mM) 250 sucrose and 20 imidazole HCl (pH 7.0) and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4°C. The resulting pellet was dissolved in blue native sample buffer containing 1% digitonin, and protein concentration was quantified in the supernatant with a BCA protein assay kit with BSA as a standard. Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 was added to the samples to a final concentration of 0.05%. The samples were separated with NativePAGE Novex precast 3–12% Bis-Tris minigels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The PVDF membranes were blocked in 3% nonfat milk dissolved in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 and immunoblotted with primary mouse MitoProfile Total OXPHOS human antibody cocktail against complex I subunit nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydrogen dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) (NDUFB8), complex II 30 kDa (SDHB), complex III core protein 2 (UQCRC2), complex IV subunit I (MTCOX2), and complex V α-subunit (ATP5A). The secondary goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP antibody was used against the primary OXPHOS human antibodies. Proteins were visualized by SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate and monitored with UltraQuant v6.0 software in molecular imaging systems (UltraLum, Claremont, CA).

Quantification of protein expression of representative subunits of OXPHOS complexes by Western blot.

Frozen atrial tissue (30–50 mg) was homogenized in an ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer with protease/phosphatase inhibitors and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Tissue extracts were separated by SDS gel electrophoresis. Proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membrane with the iBlot dry blotting system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The membrane was blocked in 5% nonfat milk dissolved in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.2% Tween 20 and immunoblotted with primary mouse MitoProfile Total OXPHOS human antibody cocktail against NDUFB8, SDHB, UQCRC2, MTCOX2, ATP5A, anti-Cyt c, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH-14C10) HRP-conjugated rabbit monoclonal antibody against Cyt c and GAPDH. The secondary goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP antibody was used against the primary OXPHOS human and anti-Cyt c antibodies. Proteins were visualized by SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate and monitored with UltraQuant v6.0 software in molecular imaging systems (UltraLum). Densitometric evaluation of protein bands was performed with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Bands corresponding to the mitochondrial complexes were normalized to the density of respective GAPDH and Cyt c bands.

Determination of 4-hydroxynonenal protein adducts.

The level of 4-HNE was measured in tissue homogenate by the OxiSelect HNE adduct competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with a commercial kit. Briefly, frozen atrial samples were homogenized in ice-cold PBS buffer with 0.1% BSA and centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 g. The 4-HNE level was assessed in supernatant according to manufacturer's recommendations.

Preparation of permeabilized fibers.

Myofibers were isolated as previously described by Anderson et al. (3). Briefly, the right atrial appendage tissue was transferred into ice-cold buffer containing (in mM) 7.23 K2EGTA, 2.77 CaK2EGTA, 20 imidazole, 20 taurine, 5.7 ATP, 14.3 phosphocreatine, 6.56 MgCl2·6H2O, and 50 MES (pH 7.1), cut into small strips (6 × 3 mm), and incubated with collagenase type I for 30–45 min at 4°C. Then pieces were washed with fresh buffer and carefully trimmed of connective tissue and fat. Fibers were mechanically separated along the longitudinal axis and permeabilized with saponin (30–50 μg/ml) for 30 min at 4°C. After permeabilization, myofibers were washed in ice-cold buffer containing (in mM) 110 K-MES (pH 7.4), 35 KCl, 1 EGTA, 5 KH2PO4, and 3 MgCl2·6H2O, and 0.02 blebbistatin with 5 mg/ml BSA and remained in the buffer until analysis at 4°C.

Analysis of mitochondrial superoxide production in myofibers.

Mitochondrial superoxide production was measured in isolated and permeabilized myofibers in a buffer containing (in mM) 110 K-MES (pH 7.4), 35 KCl, 1 EGTA, 5 KH2PO4, 3 MgCl2·6H2O, and 0.02 blebbistatin with 5 mg/ml BSA and supplemented with 100 μM ADP, 5 mM glucose, and 1 U/ml hexokinase to keep mitochondria in an energized and phosphorylating state (3). The level of superoxide production in the myofibers was determined as a change in fluorescence intensity of MitoSOX Red (λex/λem = 510/580), a mitochondrial superoxide-sensitive indicator, in response to 10 μM antimycin A exposure by time-lapse laser scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy (Olympus FV1200). Frames were acquired 30 s apart with a ×10 objective. The change in the level of superoxide production was quantified as a difference in MitoSOX Red fluorescence intensity before and after antimycin A addition when intensity reached plateau.

Materials.

Chemicals for myofiber isolation and biochemical assays, including blebbistatin and cytochrome-c oxidase kit (CYTOCOX1), were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Dulbecco's PBS and collagenase type I were purchased from Lonza BioWhittaker (Walkersville, MD). BCA protein assay kit was from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Western blot, 1D BN-PAGE reagents, MitoSOX Red, and Hoechst 33342 were purchased from Life Technologies (New York, NY). Human MitoProfile Total OXPHOS antibody cocktail was from MitoSciences (Eugene, OR). Anti-Cyt c antibody was purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA). Secondary goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and GAPDH (14C10) HRP-conjugated rabbit monoclonal antibody and protease/phosphatase inhibitors were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). OxiSelect HNE adduct competitive ELISA kit was purchased from Cell Biolabs (San Diego, CA).

Statistical analysis.

An initial step in the analysis entailed frequency counts and proportions for categorical variables, while continuous variables were summarized as the mean, SE, median, and quartiles. Association among categorical variables was performed with the χ2-test of association and Fisher's exact test, while the correlation coefficient was used to assess associations among continuous variables. A comparison between non-AF and AF groups was performed with a two-sample t-test. All tests were performed at a 5% level of significance, and statistical analysis was performed with SAS software (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and SigmaPlot (version 12.3, SYSTAT Software, San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of patients.

Right atrial appendage samples were obtained from 62 patients (n = 33 for non-AF vs. n = 29 for AF). The clinical characteristics of non-AF and AF patients are summarized in Table 1. The groups were well-matched for the presence of the risk factors for AF or its complications. There were no significant differences in age, sex distribution, body mass index (BMI), history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, heart failure, stroke, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, chronic renal failure, diabetes, left atrial volume index, type of surgery performed, or medications.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | nAF (n = 33) |

AF (n = 29) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 68 ± 2 | 71 ± 1 | 0.26 |

| Range | 48–84 | 53–81 | |

| Male, % | 39 (13) | 38 (11) | 0.91 |

| Comorbidities, % | |||

| Diabetes | 27 (9) | 38 (11) | 0.37 |

| Hypertension | 82 (27) | 83 (24) | 0.92 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 79 (26) | 62 (18) | 0.15 |

| Smoking | 58 (19) | 41 (12) | 0.20 |

| Chronic renal failure | 12 (7) | 14 (4) | 0.45 |

| Coronary artery disease | 94 (31) | 83 (24) | 0.07 |

| Heart failure | 9 (3) | 24 (7) | 0.11 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 12 (4) | 7 (2) | 0.49 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 9 (3) | 10 (3) | 0.87 |

| Stroke | 3 (1) | 10 (3) | 0.24 |

| Valve disease | 42 (14) | 52 (15) | 0.46 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 33 ± 1 | 28 ± 1 | 0.78 |

| Echocardiography parameters | |||

| LV ejection fraction, % | 60 ± 2 | 58 ± 2 | 0.36 |

| LV diastolic dimension, cm | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 0.06 |

| LV systolic dimension, cm | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 0.18 |

| Intraventricular septum thickness, cm | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.47 |

| LV posterior wall thickness, cm | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.04 | 0.82 |

| Left atrial volume index, ml (range) | 31 ± 3 (16–58) | 43 ± 4 (25–75) | 0.12 |

| Medications, % | |||

| β-Blockers | 72 (24) | 83 (24) | 0.35 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 18 (6) | 31 (9) | 0.24 |

| ACE I/ARB | 45 (15) | 48 (14) | 0.82 |

| Diuretics | 49 (16) | 69 (20) | 0.10 |

| Statins | 70 (23) | 48 (14) | 0.12 |

| Insulin | 15 (5) | 24 (7) | 0.37 |

| OHA | 15 (5) | 14 (4) | 0.88 |

| Insulin and OHA | 12 (4) | 17 (5) | 0.57 |

| Type of cardiac surgery, % | |||

| CABG alone | 58 (19) | 41 (12) | 0.20 |

| CABG and valve surgery | 39 (13) | 31 (9) | 0.49 |

| Valve replacement without CABG | 3 (1) | 17 (5) | 0.06 |

| Other | 0 (0) | 10 (3) |

Data are shown as % of total number with number of patients (n) in parentheses, except for age, body mass index, and echocardiography parameters, which are presented as means ± SE. LV, left ventricular; ACE I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II receptor antagonists; OHA, oral hypoglycemic agents; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; AF, atrial fibrillation group; nAF, non-atrial fibrillation group.

Functional activities of OXPHOS complexes.

The activity of rotenone-sensitive NADH:O2 oxidoreductase, representing the overall activity of the mitochondrial ETC, was significantly lower in atrial tissue from patients with AF compared with tissue from non-AF patients (142 ± 6 vs. 201 ± 20 ng atoms O2·min−1·CS activity−1, P = 0.03) (Fig. 2). To dissect out the specific sites responsible for the diminished ETC activity in patients with AF, the functional activities of individual complexes I–IV as well as the activity of complex V were analyzed in patients without and with AF. The functional activity of the complexes was normalized to CS activity, a mitochondrion-specific matrix protein, which was not significantly different between the two groups (323 ± 31 vs. 356 ± 37 nmol·min−1·mg NCP−1 in non-AF and AF, respectively, P = 0.49). There was significant reduction in activity of mitochondrial complex I (AF 0.06 ± 0.006 vs. non-AF 0.09 ± 0.007 nmol·min−1·CS activity−1, P = 0.02) and II (AF 0.11 ± 0.012 vs. non-AF 0.16 ± 0.012 nmol·min−1·CS activity−1, P < 0.01) activities in AF patients (Fig. 3). The functional activities of complexes III (AF 0.11 ± 0.018 vs. non-AF 0.15 ± 0.021 nmol·min−1·CS activity−1, P = 0.16) and IV (AF 0.55 ± 0.08 vs. non-AF 0.51 ± 0.06 nmol·min−1·CS activity−1, P = 0.67) were not significantly different between the two groups (Fig. 3). However, complex V activity was increased in the AF group (AF 0.21 ± 0.027 vs. non-AF 0.12 ± 0.01 nmol·min−1·CS activity−1, P < 0.01). Since the mean value for BMI in both non-AF and AF groups was >30 kg/m2 (obese group by the World Health Organization classification) (4), the impact of BMI on OXPHOS complexes also was separately analyzed and no correlation between functional activity of the complexes and BMI was observed (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Activity of NADH:O2-oxidoreductase in the right atria of patients with and without atrial fibrillation. The activity was defined with a Clark electrode and normalized to citrate synthase (CS) activity. Data are means ± SE; n = 5 for non-atrial fibrillation (nAF) group, n = 7 for atrial fibrillation (AF) group. *P < 0.05.

Fig. 3.

Functional activities of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes in the right atria of patients without (nAF) and with (AF) atrial fibrillation. Data are expressed in nanomoles per minute per citrate synthase activity and presented as means ± SE; n = 23 for nAF and n = 31 for AF. *P < 0.05.

Fig. 4.

Correlation between functional activity of oxidative phosphorylation complexes and body mass index (BMI). ○, non-atrial fibrillation (nAF); ●, atrial fibrillation (AF). Functional activity is expressed in nanomoles per minute per citrate synthase activity. *P < 0.05.

1D BN-PAGE and Western blot of OXPHOS complexes.

Figure 5A illustrates 1D BN-PAGE separation of individual OXPHOS complexes in native form in atrial homogenates. The individual OXPHOS complexes were identified by Western blot using antibodies against specific complex subunits after transfer of proteins from the BN-PAGE gel to a PVDF membrane (Fig. 5B). The overall mobility and size of the complexes were similar in AF and non-AF groups (Fig. 5, A and B), which indicated that assembly of the multisubunit complexes was preserved in AF patients. Figure 5C demonstrates expression of the representative protein subunits of the OXPHOS complexes in AF and non-AF human atrial tissue homogenates. Quantitative analysis of the bands revealed a significant reduction in expression of complex I in the AF group compared with the non-AF group (Fig. 5D, P = 0.02) without difference in the expression of the remaining four OXPHOS complexes when normalized to GAPDH. This was further confirmed by using Cyt c as a mitochondrion-specific housekeeping protein (Fig. 6, P = 0.03).

Fig. 5.

Separation and identification of mitochondrial complexes from patients without and with atrial fibrillation. A: representative gel of separated mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes I–V in native form by 1-dimensional BN-PAGE electrophoresis. B: identification of OXPHOS complexes after transferring proteins from BN-PAGE gel to PVDF membrane with MitoProfile Total OXPHOS human antibody cocktail. C and D: Western blot of individual subunits of OXPHOS complexes I–V using MitoProfile Total OXPHOS human antibody cocktail (C) and densitometry of bands from immunoblot corresponding to mitochondrial complexes normalized to density of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) band (D). MW, molecular weight of the marker; nAF, without atrial fibrillation (n = 11); AF, with atrial fibrillation (n = 11); C I–C V, complexes I–V. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

Fig. 6.

Differences in protein expression level of mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes I–V from patients without and with atrial fibrillation. A: immunoblots of representative subunits of complexes I–V using MitoProfile Total OXPHOS human antibody cocktail. B: densitometry of bands from immunoblot corresponding to mitochondrial complexes normalized to density of cytochrome c band. nAF, without atrial fibrillation (n = 5); AF, with atrial fibrillation (n = 5); C I–C V, complexes I–V. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

4-HNE protein adducts and superoxide level.

The level of 4-HNE protein adducts was significantly increased in the atrial tissue of patients with AF compared with age- and comorbidity-matched non-AF patients (AF 77.64 ± 30.02 vs. non-AF 9.83 ± 2.83 ng/mg protein, P = 0.048; Fig. 7A). Mitochondrial superoxide production in response to antimycin A, an inhibitor of complex III, as assessed by MitoSOX Red fluorescence in permeabilized myofibers, was more than sixfold higher in AF compared with non-AF patients (AF 73 ± 17 vs. non-AF 11 ± 2 arbitrary units, P = 0.03; Fig. 7, B and C).

Fig. 7.

Difference in 4-HNE protein adducts and mitochondrial superoxide level in the right atria between patients without and with atrial fibrillation. A: the level of 4-HNE was normalized to protein concentration in tissue supernatant; n = 7 for non-atrial fibrillation (nAF), n = 8 for atrial fibrillation (AF). B: representative images of changes in mitochondrial superoxide production in permeabilized myofibers from nAF and AF patients. Fibers were stained with 2 μg/ml Hoechst (λex/λem = 350/461 nm) and 2.5 μM MitoSOX Red (λex/λem = 510/580) for 30 min and imaged by time-lapse laser scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy (Olympus FV1200) with a ×10 objective. Antimycin A (AA) at 10 μM was applied to stimulate superoxide production in mitochondria. C: difference in fluorescence intensity of MitoSOX Red before and after antimycin A (15 min) exposure. Data are means ± SE; n = 8 for nAF and n = 5 for AF. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The major finding of our translational study utilizing human cardiac tissue is that a selective reduction in the mitochondrial ETC activity is present in the atria of patients with AF undergoing open-heart surgery compared with a well-matched group of patients without AF. The strong reduction in activity within the ETC was predominantly observed at the level of complexes I and II, but the assembly of the complexes was not affected by AF. The reduction in complex I functional activity was associated with reduced protein expression of the NDUFB8 subunit, while the expression level of the SDHB subunit of complex II did not change. The functional activity of complexes III and IV and the expression of their representative protein subunits were not significantly different between AF and non-AF groups. Complex V activity was increased in patients with AF. The overall lipid peroxidation, as reflected by 4-HNE protein adduct level, as well as antimycin A-induced mitochondrial superoxide production was higher in atrial tissue from AF patients. The 4-HNE level directly correlated with increased mitochondrial superoxide production in AF patients. The decrease in NADH:O2 oxidoreductase activity, representing the overall ETC activity in patients with AF, was not related to reduction in the mitochondrial content, as reflected by similar activities of CS activity in AF and non-AF patients.

Mitochondria are the major source of ATP that provides the energy to support myocardial contraction and maintenance of ionic homeostasis and cellular integrity (21, 22, 61). Under physiological conditions, >90% of energy production required for heart function comes from mitochondria and is dependent on activity of the multisubunit complexes forming the ETC (complexes I–IV) that generates the proton-motive force driving ATP synthesis through complex V. The activities of the ETC and ATP synthesis are tightly regulated to match ATP supply and demand in the heart during physiological workload (22). Any alteration in mitochondrial function is therefore expected to reduce the energetic reserves and disturb homeostatic balance during stress, resulting in impairment of cardiac electrical and mechanical functions (1, 5, 10, 11, 48, 59) and, through regulation of cell death and fibrosis, contributes to the development of the substrate for AF and its progression with aging and aging-associated diseases (39, 46, 49). Reduction in mitochondrial function has been demonstrated previously in patients with AF; however, the confounding effect of aging or disease conditions such as heart failure, stroke, mitral valve diseases, history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, chronic renal failure, diabetes, or obesity on mitochondrial function was not evaluated. Our study assessed differences in the activity of the OXPHOS complexes after careful matching of patients with and without AF for age, sex, and comorbidities, known factors that can alter mitochondrial function (22, 44, 49). Since patients in our study population were predominantly obese (BMI > 30), we additionally performed correlation analysis between the OXPHOS complexes and BMI and found that the correlation was not significant.

The reduction in functional activity of complex I in AF was associated with a significant reduction in protein expression level of the NDUFB8 subunit in complex I. Mitochondrial complex I is the largest component of the ETC, consisting of 45 protein subunits. Of these, 7 are encoded by mitochondrial DNA and 38 by nuclear genome (13). The main function of complex I is oxidation of NADH, transferring electrons from NADH to the ETC for ATP production. In addition, it has been proposed that complex I plays an essential role in the assembly of respirasomes that bring together ETC subunits, providing structural interdependence to the individual OXPHOS complexes important in channeling electron flow, controlling superoxide production (13, 38), and sensitivity of mitochondria toward mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening (28). Alterations in expression of genes and protein subunits of complex I lead to disassembly, instability of the complex, and an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, thus resulting in cardiac diseases, cardiomyopathy (7, 18), and heart failure (28). The BN-PAGE data indicate no difference in mobility of the complexes, suggesting that the structure of the complexes is not altered and a selective reduction in complex I and II activity might be due to other alterations. A reduced expression level of the NDUFB8 subunit points to the functional importance of this protein in AF, which has been reported previously to be reduced in human atria with aging and in patients with obesity (42). In our study we accounted for differences in age, diabetes, BMI, and other comorbidities.

Patients with AF had reduced functional activity in complex II, but this was not associated with expression level of SDHB subunit. Complex II is a mitochondrial membrane-bound component of the Krebs cycle. It is composed of four nuclear encoded subunits that transfer electrons from FADH2 to coenzyme Q and downstream complexes for ATP synthesis and involved in ROS production (14). The decrease in functional activity of complex II without changes in protein expression level has been previously described in a rabbit model of pressure-overload hypertrophy (22). In streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, significant decline in the cardiac OXPHOS complex I and II enzyme activity was observed without changes in complex III, IV, and V activity (30). This was associated with increased oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, and 4-HNE generation in cardiac mitochondria similar to our observation in AF patients that could be the result of reduced electron utilization along the ETC. The precise mechanism of impairment of the ETC complexes activity is not known. Proposed mechanisms include the reduction of the ETC activity due to posttranslational modifications of subunits as a result of oxidation (17, 20, 29) or carbonylation and/or alteration of mitochondrial DNA (12, 31, 32, 56) that can promote energy impairment or susceptibility to cell death and fibrosis contributing to the substrate for arrhythmogenesis or progression of AF (1, 5, 11, 20, 29). However, this needs to be further confirmed in human atrial tissue.

In our study, oligomycin A-sensitive ATPase activity was increased in atrial tissue from patients with AF, which might be a compensatory mechanism to maintain ATP production with reduced ETC activity as previously shown in a pacing-induced AF sheep model (7) to match the ATP production with consumption.

Our findings are in line with the recent report of reduction in mitochondrial function in atrial myocardial fibers from patients with metabolic syndrome who developed postoperative AF, providing a link between mitochondria and AF (37). Specifically, ADP-stimulated mitochondrial respiration supported by complex I-dependent substrates was significantly decreased in patients who subsequently developed postoperative AF, and the reduced mitochondrial respiration was an independent predictor of postoperative AF. In contrast, ADP-stimulated complex II-dependent respiration was not different but activity of complex III was reduced. These findings in human tissue, however, are not universal in other models of atrial dysfunction. In a canine model of AF after pacing-induced heart failure, a reduction in the activities of complexes III and V, without change in the activity of complexes I, II, and IV, was reported (32). Similarly, no change was reported in the activities of complex IV, ATPase, or NADH oxidase in a goat model of chronic AF (5a). Adenine nucleotides and their degradation products did not change significantly during AF (5a). In human mitochondria from heart failure patients, the ETC activity and mitochondrial function also were reported to be preserved (19). The exact cause for the discrepancy in the functional activity of the OXPHOS complexes in reported studies is not known, but it could be related to the specific substrate (structural and electrical remodeling) for AF or triggering factors, coexisting conditions, and species-dependent effects of AF on cardiac energetics.

Impairment in complex I and II activity was associated with increase in mitochondrial superoxide production and 4-HNE protein adduct level in our AF patients, in agreement with other studies indicating enhanced level of oxidative stress with elevated markers, 4-HNE (30), superoxide, diacrone-reactive oxygen metabolites (43), oxidized glutathione, oxidized thiols (41), peroxynitrite, nitric oxide synthase, and NAD(P)H oxidase (29, 47). Mitochondria from AF patients exhibited more than sixfold higher production of superoxide to antimycin A treatment compared with non-AF patients (Fig. 7, B and C). Increased oxidative stress in AF patients explains the higher level of 4-HNE (Fig. 7A) and is consistent with reduced functional activity of complexes I and II. This suggests that increased mitochondrial ROS production may underlie the oxidative stress in AF. Enhanced ROS production can predispose to myocardial injury and arrhythmogenesis (1). The relative contribution of other mitochondrial and cytosolic ROS sources contributing to AF progression is beyond the scope of the present study.

A serious limitation in studying pathophysiology at a molecular level in human tissue, particularly from the heart, is the variability in patient demographics and comorbidities, as well as in the amount of tissue obtained from a patient and the site from where the tissue was taken. This variability makes assessment difficult. Absence of a true control group also is challenging, as biopsies from healthy human hearts cannot be obtained. Previous studies have included patients with variable extent of myocardial or valvular dysfunction and comorbidities. Therefore, in the present study, we closely matched the baseline characteristics of the AF and non-AF groups of patients with respect to age, sex, myocardial dysfunction, and comorbidities known to affect mitochondrial function to clarify the effect of AF on the OXPHOS in human atrial tissue. Special care was taken to collect tissue in a standardized manner, avoiding any delays that can affect mitochondrial function. Our sample size of 62 patients is small, but the data presented are from human atrial tissue, which is difficult to obtain, especially when we apply strict inclusion and exclusion criteria to minimize the confounding effects of conditions such as severe heart failure, reduced ejection fraction, presence of comorbidities, and atrial enlargement. These conditions are known to affect mitochondrial function, and therefore patients with and without AF should be matched. We believe our careful matching of the AF and non-AF groups in terms of baseline demographics, comorbidities, cardiac structure and function, and medication is a major strength. This allows differentiation of the impact of AF on mitochondrial function, which distinguishes our study from others (12, 37, 50) that have not accounted for these important clinical differences that could affect mitochondrial bioenergetics. In our study, the observed mitochondrial dysfunction with reduced ETC activity and increased oxidative stress in AF patients is not proof of a cause-and-effect relationship for the development of AF but is an important factor that can contribute to the progression of AF substrate. Further studies utilizing interventions that can improve mitochondrial function and reduce oxidative stress can help to clarify the cause-and-effect relationship and potential therapeutic target for preventing progression and complications of AF.

In summary, our study in a well-matched group of patients with well-preserved LV function undergoing open-heart surgery provides evidence of a selective downregulation of mitochondrial ETC functional activity predominantly affecting complexes I and II with associated increase in oxidative stress in atrial tissue from patients with AF. This provides cues for further investigation to narrow down targets that can be modulated to prevent progression of the substrate that promotes AF, a common arrhythmia whose increasing prevalence and associated complications are a major public health concern.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01 HL-101240 and R01 HL-089542 and intramural Cardiac Research Award AHC 505-3657 from the Aurora Health Care Foundation.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.E. and A.J. conception and design of research; L.E., Z.A., M.C., and G.R. performed experiments; L.E. and S.O. analyzed data; L.E. and A.J. interpreted results of experiments; L.E. and U.N. prepared figures; L.E. drafted manuscript; L.E., Z.A., M.C., U.N., G.R., F.R., S.O., D.C.K., J.S., A.J.T., E.L.H., Y.S., and A.J. approved final version of manuscript; F.R., D.C.K., J.S., A.J.T., E.L.H., Y.S., and A.J. edited and revised manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge Jennifer Cooper, Kelsey Kraft, and Dr. Maharaj Singh for their technical assistance. We also are grateful to Jennifer Pfaff and Susan Nord of Aurora Cardiovascular Services for editorial preparation of the manuscript and Brian Miller and Brian Schurrer of Aurora Health Care for help with the figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akar FG, Aon MA, Tomaselli GF, O'Rourke B. The mitochondrial origin of postischemic arrhythmias. J Clin Invest 115: 3527–3535, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alasady M, Shipp NJ, Brooks AG, Lim HS, Lau DH, Barlow D, Kuklik P, Worthley MI, Roberts-Thomson KC, Saint DA, Abhayaratna W, Sanders P. Myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation: importance of atrial ischemia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 6: 738–745, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson EJ, Efird JT, Davies SW, O'Neal WT, Darden TM, Thayne KA, Katunga LA, Kindell LC, Ferguson B, Anderson CA, Chitwood WR, Koutlas TC, Williams JM, Rodriguez E, Kypson AP. Monoamine oxidase is a major determinant of redox balance in human atrial myocardium and is associated with postoperative atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 3: e000713, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anonymous. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 854: 1–452, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Akar FG, Brown DA, Zhou L, O'Rourke B. From mitochondrial dynamics to arrhythmias. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41: 1940–1948, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Ausma J, Coumans WA, Duimel H, Van der Vusse GJ, Allessie MA, Borgers M. Atrial high energy phosphate content and mitochondrial enzyme activity during chronic atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 47: 788–796, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacsi A, Woodberry M, Widger W, Papaconstantinou J, Mitra S, Peterson JW, Boldogh I. Localization of superoxide anion production to mitochondrial electron transport chain in 3-NPA-treated cells. Mitochondrion 6: 235–244, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbey O, Pierre S, Duran MJ, Sennoune S, Levy S, Maixent JM. Specific up-regulation of mitochondrial F0F1-ATPase activity after short episode of atrial fibrillation in sheep. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 11: 432–438, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker L, Kling E, Schiller E, Zeh R, Schrewe A, Hölter SM, Mossbrugger I, Calzada-Wack J, Strecker V, Wittig I, Dumitru I, Wenz T, Bender A, Aichler M, Janik D, Neff F, Walch A, Quintanilla-Fend L, Floss T, Bekeredjian R, Gailus-Durner V, Fuchs H, Wurst W, Meitinger T, Prokisch H, de Angelis MH, Klopstock T. MTO1-deficient mouse model mirrors the human phenotype showing complex I defect and cardiomyopathy. PLoS One 9: e114918, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergmeyer HU. (Editor). Methods of Enzymatic Analysis (2nd ed). New York: Verlag Chemie Weinheim Academic, 1974, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown DA, Aon MA, Frasier CR, Sloan RC, Maloney AH, Anderson EJ, O'Rourke B. Cardiac arrhythmias induced by glutathione oxidation can be inhibited by preventing mitochondrial depolarization. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 673–679, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown DA, O'Rourke B. Cardiac mitochondria and arrhythmias. Cardiovasc Res 88: 241–249, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bukowska A, Schild L, Keilhoff G, Hirte D, Neumann M, Gardemann A, Neumann KH, Röhl FW, Huth C, Goette A, Lendeckel U. Mitochondrial dysfunction and redox signaling in atrial tachyarrhythmia. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 233: 558–574, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll J, Fearnley IM, Skehel JM, Shannon RJ, Hirst J, Walker JE. Bovine complex I is a complex of 45 different subunits. J Biol Chem 281: 32724–32727, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cecchini G. Function and structure of complex II of the respiratory chain. Annu Rev Biochem 72: 77–109, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cha YM, Dzeja PP, Shen WK, Jahangir A, Hart CY, Terzic A, Redfield MM. Failing atrial myocardium: energetic deficits accompany structural remodeling and electrical instability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H1313–H1320, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaudhary KR, El-Sikhry H, Seubert JM. Mitochondria and the aging heart. J Geriatr Cardiol 8: 159–167, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen YR, Zweier JL. Cardiac mitochondria and reactive oxygen species generation. Circ Res 114: 524–537, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chouchani ET, Methner C, Buonincontri G, Hu CH, Logan A, Sawiak SJ, Murphy MP, Krieg T. Complex I deficiency due to selective loss of Ndufs4 in the mouse heart results in severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. PLoS One 9: e94157, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cordero-Reyes AM, Gupte AA, Youker KA, Loebe M, Hsueh WA, Torre-Amione G, Taegtmeyer H, Hamilton DJ. Freshly isolated mitochondria from failing human hearts exhibit preserved respiratory function. J Mol Cell Cardiol 68: 98–105, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dudley SC Jr, Hoch NE, McCann LA, Honeycutt C, Diamandopoulos L, Fukai T, Harrison DG, Dikalov SI, Langberg J. Atrial fibrillation increases production of superoxide by the left atrium and left atrial appendage: role of the NADPH and xanthine oxidases. Circulation 112: 1266–1273, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman JR, Nunnari J. Mitochondrial form and function. Nature 505: 335–343, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffiths ER, Friehs I, Scherr E, Poutias D, McGowan FX, Del Nido PJ. Electron transport chain dysfunction in neonatal pressure-overload hypertrophy precedes cardiomyocyte apoptosis independent of oxidative stress. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 139: 1609–17, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffiths EJ. Mitochondria and heart disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 942: 249–267, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmuhamedov EL, Oberlin A, Short K, Terzic A, Jahangir A. Cardiac subsarcolemmal and interfibrillar mitochondria display distinct responsiveness to protection by diazoxide. PLoS One 7: e44667, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr, Conti JB, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Murray KT, Sacco RL, Stevenson WG, Tchou PJ, Tracy CM, Yancy CW, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 64: e1–e76, 2014. [Erratum. J Am Coll Cardiol 64: December 2, 2014, p. 2305–2307.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kadenbach B. Introduction to mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Adv Exp Med Biol 748: 1–11, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalifa J, Maixent JM, Chalvidan T, Dalmasso C, Colin D, Cozma D, Laurent P, Deharo JC, Djiane P, Cozzone P, Bernard M. Energetic metabolism during acute stretch-related atrial fibrillation. Mol Cell Biochem 317: 69–75, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karamanlidis G, Lee CF, Garcia-Menendez L, Kolwicz SC Jr, Suthammarak W, Gong G, Sedensky MM, Morgan PG, Wang W, Tian R. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency increases protein acetylation and accelerates heart failure. Cell Metab 18: 239–250, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim YM, Kattach H, Ratnatunga C, Pillai R, Channon KM, Casadei B. Association of atrial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase activity with the development of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 51: 68–74, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lashin OM, Szweda PA, Szweda LI, Romani AM. Decreased complex II respiration and HNE-modified SDH subunit in diabetic heart. Free Radic Biol Med 40: 886–896, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin PH, Lee SH, Su CP, Wei YH. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA in atrial muscle of patients with atrial fibrillation. Free Radic Biol Med 35: 1310–1318, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marín-García J, Goldenthal MJ, Moe GW. Abnormal cardiac and skeletal muscle mitochondrial function in pacing-induced cardiac failure. Cardiovasc Res 52: 103–110, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathew ST, Patel J, Joseph S. Atrial fibrillation: mechanistic insights and treatment options. Eur J Intern Med 20: 672–681, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mihm MJ, Yu F, Carnes CA, Reiser PJ, McCarthy PM, Van Wagoner DR, Bauer JA. Impaired myofibrillar energetics and oxidative injury during human atrial fibrillation. Circulation 104: 174–180, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mirza M, Shen WK, Sofi A, Tran C, Jahangir A, Sultan S, Khan U, Viqar M, Cho C, Jahangir A. Frequent periodic leg movement during sleep is an unrecognized risk factor for progression of atrial fibrillation. PLoS One 8: e78359, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mirza M, Strunets A, Shen WK, Jahangir A. Mechanisms of arrhythmias and conduction disorders in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med 28: 555–573, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montaigne D, Marechal X, Lefebvre P, Modine T, Fayad G, Dehondt H, Hurt C, Coisne A, Koussa M, Remy-Jouet I, Zerimech F, Boulanger E, Lacroix D, Staels B, Neviere R. Mitochondrial dysfunction as an arrhythmogenic substrate: a translational proof-of-concept study in patients with metabolic syndrome in whom post-operative atrial fibrillation develops. J Am Coll Cardiol 62: 1466–1473, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreno-Lastres D, Fontanesi F, García-Consuegra I, Martín MA, Arenas J, Barrientos A, Ugalde C. Mitochondrial complex I plays an essential role in human respirasome assembly. Cell Metab 15: 324–325, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moslehi J, DePinho RA, Sahin E. Telomeres and mitochondria in the aging heart. Circ Res 110: 1226–1237, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman MJ, Cushman M, de Ferranti S, Després JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Willey JZ, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB, American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 131: 434–441, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neuman RB, Bloom HL, Shukrullah I, Darrow LA, Kleinbaum D, Jones DP, Dudley SC Jr. Oxidative stress markers are associated with persistent atrial fibrillation. Clin Chem 53: 1652–1657, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niemann B, Chen Y, Teschner M, Li L, Silber RE, Rohrbach S. Obesity induces signs of premature cardiac aging in younger patients: the role of mitochondria. J Am Coll Cardiol 57: 577–585, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okada A, Kashima Y, Tomita T, Takeuchi T, Aizawa K, Takahashi M, Ikeda U. Characterization of cardiac oxidative stress levels in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Vessels 31: 80–87, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pathak RK, Mahajan R, Lau DH, Sanders P. The implications of obesity for cardiac arrhythmia mechanisms and management. Can J Cardiol 31: 203–210, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Preston CC, Oberlin AS, Holmuhamedov EL, Gupta A, Sagar S, Syed RH, Siddiqui SA, Raghavakaimal S, Terzic A, Jahangir A. Aging-induced alterations in gene transcripts and functional activity of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes in the heart. Mech Ageing Dev 129: 304–312, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reilly SN, Jayaram R, Nahar K, Antoniades C, Verheule S, Channon KM, Alp NJ, Schotten U, Casadei B. Atrial sources of reactive oxygen species vary with the duration and substrate of atrial fibrillation: implications for the antiarrhythmic effect of statins. Circulation 124: 1107–1117, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rutledge C, Dudley S. Mitochondria and arrhythmias. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 11: 799–801, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwarz K, Siddiqi N, Singh S, Neil CJ, Dawson DK, Frenneaux MP. The breathing heart—mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction in cardiac disease. Int J Cardiol 171: 134–143, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seppet E, Eimre M, Peet N, Paju K, Orlova E, Ress M, Kõvask S, Piirsoo A, Saks VA, Gellerich FN, Zierz S, Seppet EK. Compartmentation of energy metabolism in atrial myocardium of patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Mol Cell Biochem 270: 49–61, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimano M, Shibata R, Inden Y, Yoshida N, Uchikawa T, Tsuji Y, Murohara T. Reactive oxidative metabolites are associated with atrial conduction disturbance in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 6: 935–940, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strunets A, Mirza M, Sra J, Jahangir A. Novel anticoagulants for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: safety issues in the elderly. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 6: 677–689, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takigawa M, Takahashi A, Kuwahara T, Okubo K, Takahashi Y, Watari Y, Takagi K, Fujino T, Kimura S, Hikita H, Tomita M, Hirao K, Isobe M. Long-term follow-up after catheter ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: the incidence of recurrence and progression of atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 7: 267–273, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trounce IA, Kim YL, Jun AS, Wallace DC. Assessment of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in patient muscle biopsies, lymphoblasts, and transmitochondrial cell lines. Methods Enzymol 264: 484–509, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trumbeckaite S, Opalka JR, Neuhof C, Zierz S, Gellerich FN. Different sensitivity of rabbit heart and skeletal muscle to endotoxin-induced impairment of mitochondrial function. Eur J Biochem 268: 1422–1429, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsuboi M, Hisatome I, Morisaki T, Tanaka M, Tomikura Y, Takeda S, Shimoyama M, Ohtahara A, Ogino K, Igawa O, Shigemasa C, Ohgi S, Nanba E. Mitochondrial DNA deletion associated with the reduction of adenine nucleotides in human atrium and atrial fibrillation. Eur J Clin Invest 31: 489–496, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Turagam MK, Downey FX, Kress DC, Sra J, Tajik AJ, Jahangir A. Pharmacological strategies for prevention of postoperative atrial fibrillation. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 8: 233–250, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turagam MK, Mirza M, Werner PH, Sra J, Kress DC, Tajik AJ, Jahangir A. Circulating biomarkers predictive of postoperative atrial fibrillation. Cardiol Rev 24: 76–87, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Bragt KA, Nasrallah HM, Kuiper M, Luiken JJ, Schotten U, Verheule S. Atrial supply-demand balance in healthy adult pigs: coronary blood flow, oxygen extraction, and lactate production during acute atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 101: 9–19, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Voigt N, Heijman J, Wang Q, Chiang DY, Li N, Karck M, Wehrens XH, Nattel S, Dobrev D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of atrial arrhythmogenesis in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Circulation 129: 145–156, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang KC, Bonini MG, Dudley SC Jr. Mitochondria and arrhythmias. Free Radic Biol Med 71: 351–361, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Youn JY, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Chen H, Liu D, Ping P, Weiss JN, Cai H. Oxidative stress in atrial fibrillation: an emerging role of NADPH oxidase. J Mol Cell Cardiol 62: 72–79, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]