Abstract

Mammalian hibernators adapt to prolonged periods of immobility, hypometabolism, hypothermia, and oxidative stress, each capable of reducing bone marrow activity. In this study bone marrow transcriptomes were compared among thirteen-lined ground squirrels collected in July, winter torpor, and winter interbout arousal (IBA). The results were consistent with a suppression of acquired immune responses, and a shift to innate immune responses during hibernation through higher complement expression. Consistent with the increase in adipocytes found in bone marrow of hibernators, expression of genes associated with white adipose tissue are higher during hibernation. Genes that should strengthen the bone by increasing extracellular matrix were higher during hibernation, especially the collagen genes. Finally, expression of heat shock proteins were lower, and cold-response genes were higher, during hibernation. No differential expression of hematopoietic genes involved in erythrocyte or megakaryocyte production was observed. This global view of the changes in the bone marrow transcriptome over both short term (torpor vs. IBA) and long term (torpor vs. July) hypothermia can explain several observations made about circulating blood cells and the structure and strength of the bone during hibernation.

Keywords: erythrocyte, leukocyte, megakaryocyte, osteoblast, adipose

bone marrow is a complex organ consisting of many different cell types and stem cell pools. These cells express both unique and common sets of genes and likely influence each other's activities. Hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into lymphoid progenitor cells that produce natural killer cells and lymphocytes, or into myeloid progenitor cells that give rise to erythrocytes, the remaining leukocytes, and megakaryocytes. Megakaryocytes in turn shed anucleated platelets involved in blood clotting and inflammation. Bone marrow resident mesenchymal stem cells can differentiate to produce resident bone cells including osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes (64). Osteoblasts can terminally differentiate into osteocytes and are involved in maintaining bone strength and extracellular matrix production. Bone marrow adipose composition is affected by age, diet, and disease states. Bone marrow may also contain skeletal muscle and hepatocyte stem cell pools. Because of the rapid rate of mitosis by multiple resident stem cell pools, bone marrow is sensitive to damage by radiation and chemotherapy, leaving patients immunocompromised and anemic (25). Bone mineral density and collagen are decreased by prolonged disuse such as bed rest or immobilization (45, 86). Recent studies have also demonstrated an increase in neutrophils, natural killer cells, and lymphocytes and a decrease in monocytes in patients subjected to 60 days of bed rest (38). Finally, bone marrow adipocytes increase in patients with spinal cord injury (58) and after long-term bed-rest (91).

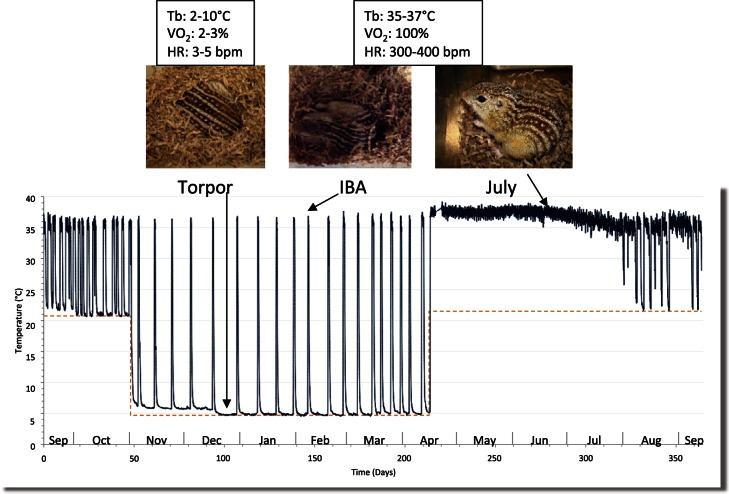

During hibernation, mammals enter long periods of torpor characterized by inactivity, reduced body temperature, metabolism, and heart rate. These are interrupted by short periodic interbout arousals (IBAs) in which the animals are active and have a normothermic physiology for 12–18 h (Fig. 1). During torpor, thirteen-lined ground squirrels (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus) have adapted to prolonged periods of immobility, hypometabolism, hypothermia, and oxidative stress, each capable of reducing bone marrow activity (49, 53). In one study, irradiation of hibernating ground squirrels showed a delay in bone marrow damage until after the animals had aroused (14). Most of the previous work on hibernation related to the function of bone marrow has focused on levels of circulating blood cells made in the bone marrow and bone strength. Erythrocyte counts remain relatively constant through these fluctuations in body temperature and blood flow. In contrast, platelet and leukocyte levels drop dramatically during torpor in a temperature-dependent manner and return to normal levels within hours postarousal with similar temperature-dependent trends seen in nonhibernators (9–12, 22, 65, 77, 79, 81, 87, 89, 90, 99). Lymphocytes are sequestered in peripheral lymphoid tissues (11, 44), while neutrophils marginate to blood vessel walls in the lung (8, 12). The location of sequestered platelets and monocytes during torpor is currently unknown. Because of the rapid rates of clearance of these cells from the blood in torpor and release upon arousal, variation in the rate of blood cell synthesis is not thought to play a role in blood cell levels as animals go in and out of torpor (9). Torpor also has an effect on leukocyte activity, decreasing both primary innate (16) and secondary acquired (15, 60) immune responses. Published studies have not looked at bone marrow genes involved in the production or activity of these cells but focused on the effects of hibernation on their activity and clearance.

Fig. 1.

Graph showing body temperature tracings (solid line) of a thirteen-lined ground squirrel measured using a surgically implanted transmitter. The dashed orange line represents the ambient (environmental) temperature, which is lowered to 5°C on November 1 and raised back to 23°C in March or April depending on the experiment. Periodic interbout arousals (IBAs) are seen as regular spikes in body temperature despite a constant ambient temperature of 5°C. Characteristic measurements of body temperature (Tb), oxygen consumption (V̇o2), and heart rate (HR) during torpor (adapted from Refs. 96a, 96b).

Bone marrow becomes reversibly enriched with adipocytes during hibernation, potentially crowding out other cell types. More bone marrow adipocytes also suppresses osteoblasts (82) and hematopoietic stem cells through paracrine signaling (87). Hibernating mammals do not suffer from significant loss in bone strength despite 6 mo of relative inactivity (24, 55, 92, 100, 101). The mechanism of this adaptation appears to differ in deep hibernators like ground squirrels, which show some loss of bone cells, while shallower hibernators like bears retain their cellular integrity (101). Understanding the molecular adaptations (3) in bone marrow that allow hibernating mammals to avoid damage could have direct clinical applications in human disorders that affect blood cell numbers and bone loss due to disuse (29, 38, 39, 82, 91). In this study the bone marrow transcriptome from July nonhibernating, winter torpid, and winter IBA ground squirrels was analyzed for potential impacts on bone metabolism and blood cell activity.

METHODS

Animals.

Ground squirrels were born in captivity and housed at University of Wisconsin-La Crosse UW-L following protocols submitted to and approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Nonhibernating animals were housed individually in rat caging on a Wisconsin photoperiod and implanted with a temperature transponder (IPTT-300, BioMedic Data Systems) and body temperatures monitored with a hand-held reader. In the fall, when an animal's body temperature dropped to 25°C (ambient), animals were placed in 8 in × 8 in plastic containers with bedding and moved into a 4°C hibernaculum. Animals were visually checked daily for arousal. Blood was collected from the tail arteries of nonhibernating ground squirrels while under anesthesia with isoflurane (1.5- 5%) in one-ninth volume of acid-citrate-dextrose. Organs were collected in January from torpid and IBA and in July from nonhibernating animals after carbon dioxide asphyxiation followed by exsanguination and were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Six animals were used in each group, July nonhibernators, January torpor, and January IBA. We planned to use equal numbers of males and females but were only able to get high-quality RNA from half of the animals. In the final samples that were used, the age, weight, and sex of animals were not significantly different between groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Average age and weights of ground squirrels in this study

| Stage of Annual Cycle | Sex (n) | Age, mo | Weight, g |

|---|---|---|---|

| Torpor | M (4) | 18.8 ± 12.3 | 150 ± 41 |

| F (2) | 9 ± 0 | 222 | |

| IBA | M (5) | 15.8 ± 7.8 | 164 ± 13 |

| F (1) | 8 | 168 | |

| Nonhibernating | M (4) | 17.3 ± 5.6 | 185 ± 30 |

| F (2) | 19 ± 8 | 205 ± 27 |

M, male; F, female; IBA, interbout arousal.

Analysis of blood and bone tissues.

Blood cell counts were performed with a HemaVet HV950 (Drew Scientific, Waterbury, CT), and random samples were confirmed by manually counting blood smears. To examine bone marrow histology, femurs were collected and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, the bone was decalcified with DeltaCAL and paraffin-embedded. Sections of 4 μm were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to analyze bone marrow. The average area of each field occupied by adipose was measured using Image J. Megakaryocytes were counted, and their size measured using Image J. To stain for collagen, femurs and the knee joint were prepared as above and stained with trichrome stain. To ensure the cartilage was intact some muscle tissue was left attached to the bone.

RNA isolation and sequencing.

Femurs were isolated, and as much muscle as possible scraped from the shaft of the femur. The head and condyles were left intact; each femur was frozen in a separate screw cap tube in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. The shaft of the femur was broken in half on a −20°C metal plate, and Trizol reagent was immediately injected into the bone via syringes with 25-gauge needles. The bone marrow was collected in a microfuge tube and extracted following the Trizol instructions using bromochloropropane to separate organic and aqueous phases. The aqueous phase containing RNA was then purified a second time with a Qiagen RNeasy kit using the DNase treatment to remove genomic DNA. Eluted RNA was quantified on a NanoDrop, and the profile analyzed with an Agilent RNA NanoChip. We used 1 μg of RNA from each sample as a template for cDNA synthesis, and these were ligated with a unique indexing tag creating 18 libraries that were then analyzed on an Agilent DNA1000 chip. The cDNA libraries were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform, single 100 base pair reads. After removal of low-quality reads, the 18 samples had a minimum of 7 million reads, with an average of 9.4 million reads per sample. Reads were mapped to contigs assembled by Trinity from this experiment and previous work (36, 83), using only the portion of the contigs within 100 bases of a predicted coding domain. Illumina reads were normalized by upper quartile normalization and then tested for differential expression using DESeq (2) after prefiltering by requiring at least a 50% change between some pair of time points by at least 100 average reads in at least one time point. A false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.05 was required using the Benjamini-Hochberg method (6). The P values corresponding to this method are usually smaller than 0.05, and as the results were prefiltered by requiring a 50% change, the P value cut-offs were 0.043 for torpor-summer comparisons, 0.039 for IBA-summer, and 0.0083 for torpor-IBA. Genes showing at least a twofold increase (n = 177) or decrease (n = 140) in expression between torpid and July animals were analyzed separately using Gene Ontology (88). This allowed gene classification by their expression in different bone marrow cell types with the goal of seeing how hibernation affects the diverse functions of bone marrow.

RESULTS

A total of 6,639 genes had at least 100 average reads in at least one time point, with 5,343 showing no differential expression between any of the time points (Supplemental Data S1).1 Of the remaining genes, 11 showed differential expression between all three time points, 103 were differentially expressed in torpor relative to IBA or July, 629 were differentially expressed in July relative to hibernation, 397 were differentially expressed between torpor and July, and 154 genes were differentially expressed between IBA and July animals. Genes showing at least twofold changes in expression (389 total) were grouped by their expression in different bone marrow cell types or cellular pathways using Gene Ontology (88) to determine how hibernation affects the diverse functions of bone marrow (Table 2). Bone marrow makes blood cells (leukocytes, erythrocytes, and platelets) and contains adipocytes and bone producing cells like osteoblasts. Bone marrow stem cells also perform cellular activities that could be affected by changes induced during transitioning in and out of torpor including regulation of the cell cycle, and response to hypoxia, hypothermia, and cellular damage.

Table 2.

Gene ontology clustering of genes showing twofold or greater changes in torpor and July animals

| GO Biological Process | Fold Enrichment |

|---|---|

| Twofold or greater decrease | |

| Metabolism | 1.8 |

| Nucleotide metabolism | 2.2 |

| Heat shock | 3.7 |

| Pathogen responses | 4.3 |

| Cell cycle | 5.7 |

| Signaling | 5.7 |

| Inhibition of apopotosis | 8.2 |

| Immune system | 16.7 |

| Twofold or greater increase | |

| Angiogenesis | 38.1 |

| Leukocyte migration | 43.8 |

| Neutrophil activity | 128.6 |

Leukocytes.

Among the genes showing at least a twofold decrease in expression in torpid animals relative to July animals, gene ontology analysis revealed an enrichment of genes involved in leukocyte migration, neutrophil activity, the immune system, and response to pathogens (Table 2). The analysis also revealed an enrichment of genes involved in macrophage activity among the genes showing at least a twofold increase in expression in torpid animals relative to July animals (Table 2). A total of 46 genes known to be involved in leukocyte activity were differentially expressed, with 44 of these showing differences between animals in torpor and July animals (Table 3). A general pattern emerged in which the majority of genes with higher expression in torpid animals were also higher in IBA animals, both stages of hibernation (19/22). In contrast, the majority of genes showing a decrease during torpor were higher in both IBA and July animals (16/22), consistent with regulation by body temperature or metabolic activity and not by hibernation. The functions of these differentially expressed genes could be further clustered into those associated with macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and innate immune responses. Expression of five genes (CHI3L1, AOC3, TARM1, SF3B1, TLR2) involved macrophage function and extracellular matrix (ECM) production was higher during torpor and IBA when compared with July nonhibernators. An additional seven genes (CD163, ILIB, CXCR2, C5AR1, IFIT3, TLR3, CD53) were expressed less in torpor, and in these cases IBA and nonhibernating expression was the same (Table 3). These genes were predominantly receptors for cytokines and viruses. A minority (5/15) of differentially expressed lymphocyte genes showed higher expression in torpor and IBA (NNAT, MCAM, CCL19, CD99, IRF2BP2). Expression during torpor in the remaining genes was less than that of IBA and July animals (Table 1). The majority of genes (11/12) involved in innate immunity were expressed at a greater level in torpor than IBA or July samples. In most cases IBA expression was also greater than in July samples, resulting in a gradient of expression (Table 3). Complement C3 was highly expressed in July animals yet showed a 3.6-fold increase in torpor. Analysis of the other complement genes expressed in bone marrow revealed no change in the three C1Q genes, but significant twofold increases in C1R, C1S, and C2. As seen in other studies, circulating blood leukocyte levels decreased during torpor and returned to normal levels within 2 h postarousal or during an IBA (Table 4). Differential analysis revealed that the majority of the decrease was due to a 5- to 10-fold drop in neutrophils and monocytes, with lymphocytes, eosinophils, and basophils showing smaller changes.

Table 3.

Normalized average mRNA counts of immune system genes

| Name | Torpor | IBA | July | Torpor:July | Cells | Tor:IBA | Tor:July | IBA:July |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NNAT | 1,344 | 676 | 44 | 30.5 | LY | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| CHI3L1 | 2,589 | 2,041 | 148 | 17.5 | NM | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| ITGA7 | 178 | 137 | 29 | 6.1 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | ||

| PTGDS | 189 | 124 | 32 | 5.9 | IN | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| AOC3 | 157 | 152 | 29 | 5.4 | NM | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| C3 | 74,655 | 47,020 | 14,677 | 5.1 | IN | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| C1QTNF1 | 1,752 | 1,212 | 371 | 4.7 | IN | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| LTC4S | 327 | 240 | 89 | 3.7 | IN | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| MCAM | 143 | 137 | 40 | 3.6 | LY | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| CCL19 | 78 | 111 | 22 | 3.5 | LY | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| TARM1 | 133 | 89 | 38 | 3.5 | NM | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| SF3B1 | 28,536 | 24,858 | 8,243 | 3.5 | NM | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| CD99 | 411 | 322 | 150 | 2.7 | LY | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| TLR2 | 2,167 | 1,290 | 881 | 2.5 | NM | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| CIRBP | 1,669 | 1,042 | 725 | 2.3 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | ||

| IFI27L2 | 825 | 611 | 413 | 2.0 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | ||

| LRP1 | 579 | 635 | 309 | 1.9 | NM | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| LRP5 | 127 | 136 | 94 | 1.4 | NM | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| MALT1 | 125 | 141 | 103 | 1.2 | IN | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| PTGES3 | 690 | 798 | 1,088 | 0.6 | IN | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| DNTT | 37 | 30 | 108 | 0.3 | LY | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| CD163 | 19 | 25 | 138 | 0.1 | NM | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| TXNIP | 2,683 | 1,193 | 870 | 3.1 | IN | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| IRF2BP2 | 706 | 380 | 387 | 1.8 | LY | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| CD59 | 65 | 118 | 102 | 0.6 | IN | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| IRF1 | 122 | 216 | 249 | 0.5 | LY | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| IL1B | 47 | 190 | 189 | 0.2 | NM | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| CXCR2 | 50 | 223 | 202 | 0.2 | NM | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| CXCR4 | 255 | 1,083 | 1,108 | 0.2 | LY | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| C5AR1 | 19 | 142 | 127 | 0.1 | NM | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | |

| AOAH | 145 | 111 | 73 | 2.0 | IN | P < 0.05 | ||

| ID2 | 218 | 133 | 117 | 1.9 | IN | P < 0.05 | ||

| IRF8 | 143 | 142 | 90 | 1.6 | IN | P < 0.05 | ||

| IRF2 | 188 | 310 | 341 | 0.6 | LY | P < 0.05 | ||

| LRMP | 171 | 264 | 312 | 0.5 | LY | P < 0.05 | ||

| ALOX15 | 1,013 | 1,226 | 2,060 | 0.5 | LY | P < 0.05 | ||

| IFIT3 | 79 | 131 | 165 | 0.5 | NM | P < 0.05 | ||

| CD79B | 39 | 44 | 155 | 0.3 | LY | P < 0.05 | ||

| IFIT1B | 35 | 83 | 140 | 0.3 | P < 0.05 | |||

| TLR3 | 63 | 306 | 379 | 0.2 | NM | P < 0.05 | ||

| MS4A1 | 16 | 42 | 117 | 0.1 | LY | P < 0.05 | ||

| CYR61 | 437 | 193 | 90 | 4.9 | IN | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 |

| LENG1 | 32 | 48 | 109 | 0.3 | LY | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 |

| BTG2 | 80 | 145 | 296 | 0.3 | LY | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 |

| PTGES | 42 | 115 | 31 | 1.4 | IN | P < 0.05 | ||

| CD53 | 217 | 368 | 293 | 0.7 | NM | P < 0.05 |

Genes expressed by: LY, lymphocytes (LY), neutrophils and monocytes (NM), innate immunity (IN). IBA, interbout arousal.

Table 4.

Blood cell parameters of animals collected in July, winter torpor, or winter IBA

| Cell Type | July (n = 9) |

Torpid (n = 10) |

IBA (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBC, × 106/μl | 8.89 ± 1.17 | 9.26 ± 2.10 | 9.65 ± 0.86 |

| Mean corpuscular volume, fl | 60.6 ± 4.1 | 52.6 ± 2.7† | 60.4 ± 3.8 |

| Hematocrit, % | 45.6 ± 5.8 | 48.5 ± 10.3 | 47.5 ± 4.0 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 14.1 ± 1.6 | 14.5 ± 1.5 | 14.9 ± 1.9 |

| Platelets, ×103/μl | 399 ± 58 | 34 ± 17† | 484 ± 115 |

| Mean platelet volume, fl | 3.74 ± 0.24 | 4.29 ± 0.56* | 4.52 ± 0.37* |

| WBC, ×103/μl | 5.97 ± 2.26 | 0.86 ± 0.50† | 5.30 ± 0.99 |

| Neutrophils | 3.48 ± 2.69 | 0.34 ± 0.21† | 3.75 ± 0.81 |

| Lymphocytes | 1.89 ± 1.73 | 0.44 ± 0.31* | 0.62 ± 0.35 |

| Monocytes | 0.45 ± 0.43 | 0.07 ± 0.06† | 0.87 ± 0.36 |

| Eosinophils | 0.12 ± 0.19 | 0.01 ± 0.01† | 0.05 ± 0.05 |

| Basophils | 0.02 ± 0.07 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

RBC, red blood cells; WBC, white blood cells.

Significant difference from July (ANOVA, P < 0.05).

Significant difference from July and IBA (ANOVA, P < 0.05).

Erythrocytes.

No significant changes were observed in circulating erythrocyte counts, hematocrit, or total hemoglobin between July, torpor, and IBA animals (Table 4). The only significant difference was a decrease in the mean corpuscular volume of erythrocytes in torpid animals, which occurs when erythrocytes are in circulation for a long time. Consistent with steady blood hemoglobin levels, hemoglobin A and B transcripts were abundant and only showed differential expression between the IBA and July time points. Counts in torpor, IBA, and July samples were 194,505, 123,678, 185,842 for HBA and 722,491, 553,568, and 825,650 for HBB, respectively. Most other differentially expressed erythropoietic genes displayed less than twofold variation, with a similar distribution between higher and lower expression during torpor. One notable exception was the highly expressed SF3B1 transcript, which showed a threefold increase in expression between hibernating (torpor with 28,536 counts and IBA with 24,858 counts) and July samples with 8,243 counts.

Megakaryocytes.

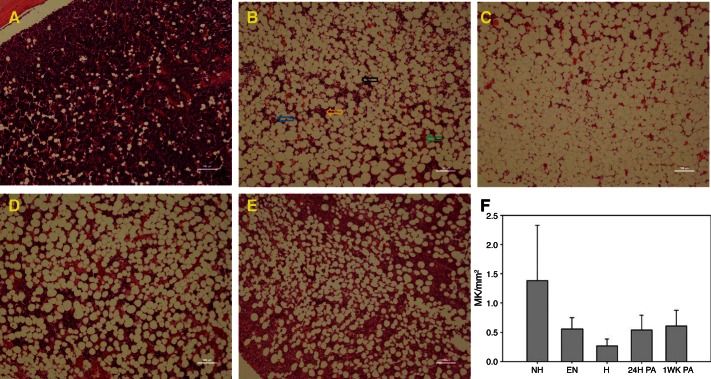

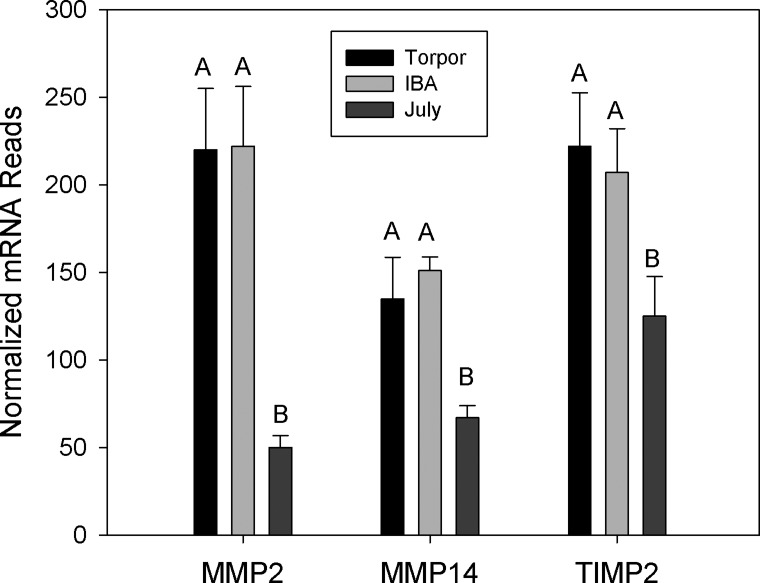

Mature megakaryocytes in the bone marrow have a ploidy of 32N to 64N and through exvagination of their plasma membrane form small anucleated platelets. During hibernation, megakaryocyte levels dropped threefold (Fig. 2F), while circulating platelet levels dropped 10-fold during torpor and rebounded to normal levels during IBA (Table 4). The mean platelet volume of both torpid and IBA platelets were larger than those in nonhibernating animals, suggesting that platelet production is still occurring during IBA (Table 4). Of the genes known to be expressed specifically by megakaryocytes only a few showed significant greater than twofold changes. The serine protease inhibitor plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI1) dropped 3.7-fold during torpor, while metallopeptidases 2 and 14 (MMP2, MMP14) were 3.8- and 2.3-fold higher, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Bone marrow from femurs isolated from animals at the following time points: nonhibernating (July) (A), entrance into hibernation (October) (B), IBA (January) (C), 1 day post-Spring arousal (D), and 1 wk post-Spring arousal (March) (E). Samples were paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (A–E). In B, arrows indicate cell types found in A–E. Blue, megakaryocyte; orange, leukocytes; black, adipocyte; green, erythrocyte. F: mature megakaryocyte counts per mm2 at each time point: NH, July nonhibernator; EN, October entrance into hibernation; H, January hibernator; 24H PA, 24 h post-Spring arousal; 1WK PA, 1 wk post-Spring arousal. Error bars represent SE for n = 6 animals. Size bar is 100 μm in all panels.

Adipose.

Gene ontology analysis revealed an enrichment of lipid metabolism genes in hibernating animals (Table 2). During the torpor and IBA time points the squirrels must survive on their lipid stores, resulting in a shift away from glucose metabolism in most tissues. A profound accumulation and then loss of bone marrow adipocytes occurs during annual cycle in ground squirrel femurs (Fig. 2, A–E). A number of genes involved in the storage and modification of triacylglycerols were higher in torpor and IBA such as ACSL1 (acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 1), PPARG (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma), and PNLIP (pancreatic lipase). In addition some genes in these pathways showed a significant difference only between torpor and July, the most striking being CIDEC (cell death-inducing DFFA-like effector c), PLIN1, perilipin 1, DGAT2 (diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2), PNPLA2 (patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 2), LPL (lipoprotein lipase), and LIPE (lipase, hormone-sensitive). Some genes involved in desaturation of fatty acids had contrasting expression profiles: FADS1, FADS2, and FADS6 (fatty acid desaturases) had significant drops during torpor compared with July, while FADS3 was lower in July. CETP (cholesteryl ester transfer protein) was higher in torpor and IBA than July, perhaps indicating higher cholesterol consumption or mobilization by the bone marrow. Similarly AQP3 (aquaporin 3) and AQP7 (aquaporin 7), which facilitate the transport of glycerol across the cell membrane, were higher in torpor and IBA, consistent with higher triacylglycerol metabolism.

SLC16A1 (solute carrier family 16, member 1), a transporter of ketone bodies, was fivefold higher in July animals than in torpor but was not differentially expressed between July and IBA animals. This is somewhat surprising given that this gene is upregulated in the brain during hibernation (4). PCK1 (phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1), which catalyzes the rate-limiting step in gluconeogenesis, is one of the most highly upregulated genes with a 22-fold increase in torpor relative to July animals. Since erythrocytes lack mitochondria and rely on anaerobic glycolysis of glucose for energy, their production in bone marrow during hibernation may require gluconeogenesis. Consequently, there may be less need for the transport of ketone bodies into bone marrow during hibernation.

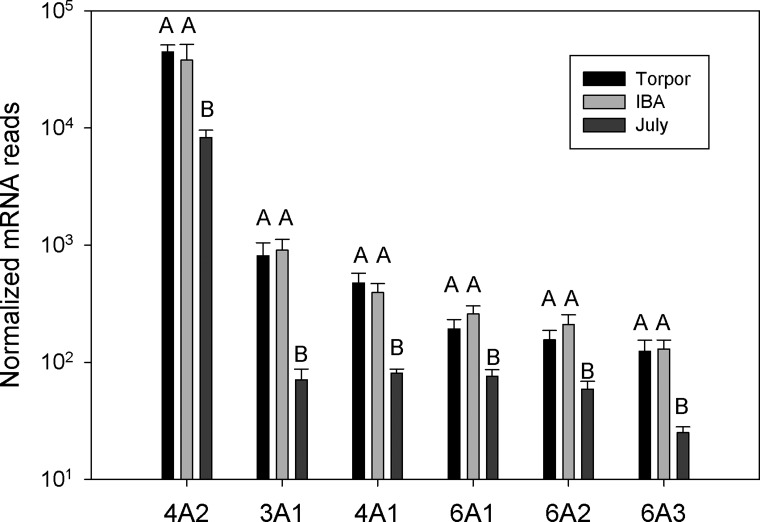

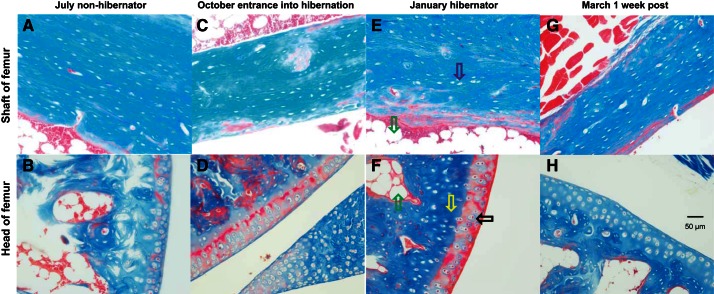

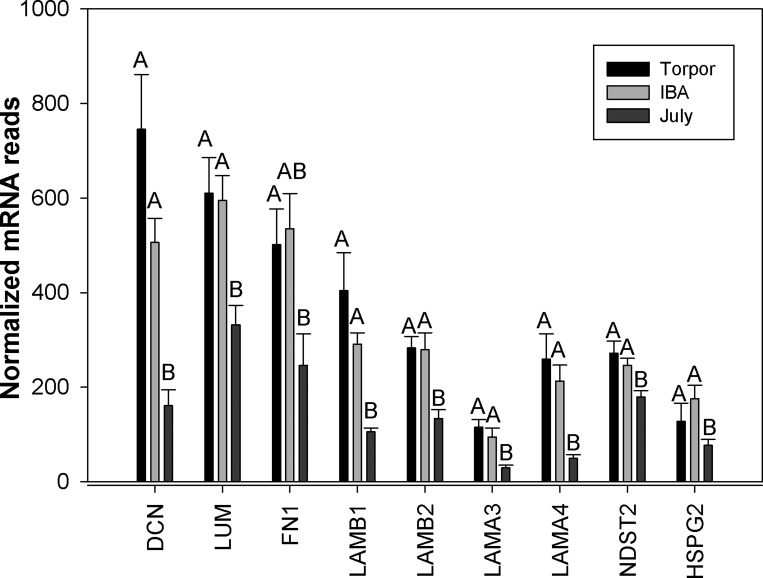

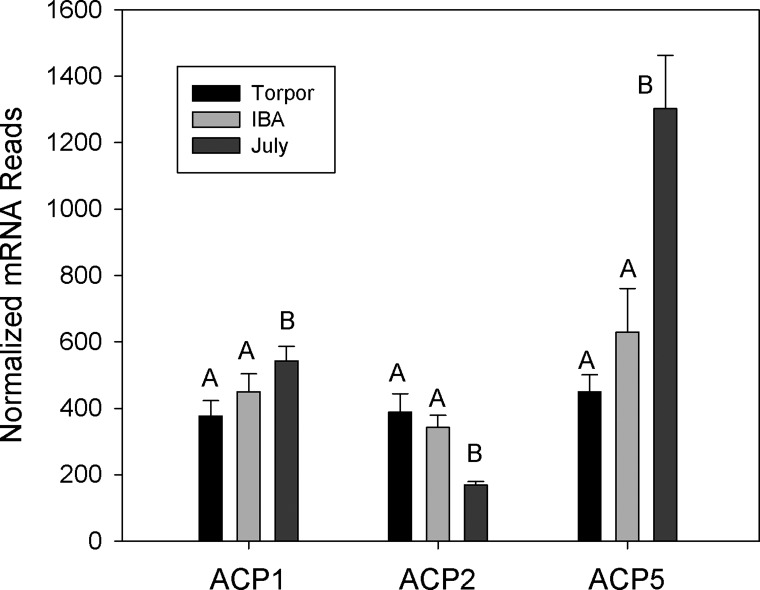

ECM.

Gene ontology analysis revealed an enrichment of adhesion and ECM genes in those genes showing at least a twofold increase in expression in torpid animals (Table 2). Bone marrow contains fibroblasts, osteoblasts and osteocytes responsible for production of ECM proteins including collagen, laminin, decorin, and fibronectin (19). All 22 of the ECM genes displaying significant differential expression were higher in hibernation (torpor and IBA) than in July, with an average 3.8-fold increase. The collagen genes were among the most highly expressed with a 5.2-fold average increase during hibernation and due to the large range of expression these are graphed in log scale (Fig. 3). Trichrome staining revealed no dramatic changes in overall collagen deposition in the shaft or head of the femur (Fig. 4). However, differences were observed in the articular cartilage, with stronger eosin staining observed in October active animals and winter hibernators (Fig. 4, D and F), consistent with a 2.5-fold increase in expression of proteoglycan and ECM protein mRNAs (Fig. 5). Three matrix-remodeling enzymes displayed an average 2.5-fold increase in mRNA expression during hibernation (Fig. 6). In contrast, only four of 15 genes specific to osteoblasts and osteoclasts showed differential expression, and these were split between an increase or decrease during hibernation. These include four acid phosphatase genes that can release calcium from bone through a demineralization process; ACP1 and ACP5 were lower, and ACP2 was higher during hibernation (Fig. 7).

Fig. 3.

Specific collagen genes expressed in bone marrow isolated from July, Torpor, and IBA animals (n = 6 for each condition). Due to the large variation in expression, numbers are graphed on a log scale. Error bars represent SE. The letters above each bar represent post hoc pair-wise comparisons to determine significance between collection points. Any collection point not connected by the same letter is significantly different [false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05].

Fig. 4.

Femur shafts (top) and heads (bottom) stained with Masson's trichrome and magnified ×200. Collagen and bone will stain blue, muscle and keratin stain red, and cytoplasm is pink. A, B: July nonhibernators. C, D: October entrance into hibernation. E, F: January hibernators. G, H: March animals 1 wk postarousal. Arrows indicate the following structures: Black, chondrocytes in the articular cartilage; yellow, collagen-rich deep matrix; green, adipocyte in bone marrow; purple, osteocyte; blue, skeletal muscle. Size bar is 50 μm in all panels.

Fig. 5.

Extracellular matrix genes expressed in bone marrow isolated from July, Torpor, and IBA animals (n = 6 for each condition). Error bars represent SE. The letters above each bar represent post hoc pair-wise comparisons to determine significance between collection points. Any collection point not connected by the same letter is significantly different (FDR < 0.05). DCN, Decorin; LUM, Lumican; FN1, Fibronectin; LAM, Laminin; NDST2, heparan glucosaminyl N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase; HSPG2, heparin sulfate proteoglycan 2.

Fig. 6.

Matrix remodeling metallopeptidase genes expressed in bone marrow isolated from July, Torpor, and IBA animals (n = 6 for each condition). Error bars represent SE. The letters above each bar represent post hoc pair-wise comparisons to determine significance between collection points. Any collection point not connected by the same letter is significantly different (FDR < 0.05). MMP, matrix metallopeptidase; TIMP2, TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 2.

Fig. 7.

Acid phosphatase (ACP) genes expressed in bone marrow isolated from July, Torpor, and IBA animals (n = 6 for each condition). Error bars represent SE. The letters above each bar represent post hoc pair-wise comparisons to determine significance between collection points. Any collection point not connected by the same letter is significantly different (FDR < 0.05).

Cell cycle and proteolysis.

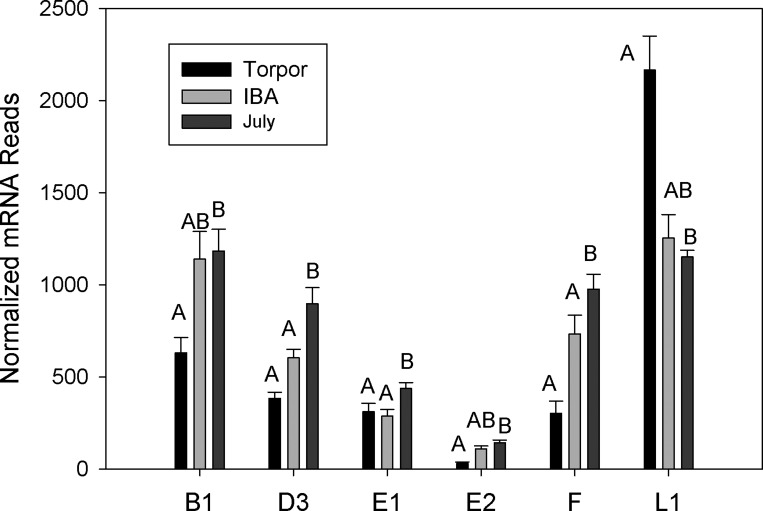

Gene ontology analysis revealed an enrichment of cell cycle, signaling, heat shock response, and apoptotic genes showing at least a twofold decrease in expression in torpid animals (Table 2). Because bone marrow contains so many stem cells pools, expression of genes regulating the cell cycle were examined. Only one of the 14 cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) detected was differentially expressed (CDK17), with a less than twofold decrease in torpor. Six of 15 cyclins found in the transcriptome were differentially expressed (Fig. 8). Cyclin E2, was fivefold lower in torpor compared with IBA and July animals, while cyclin L1 was twofold higher. In contrast seven of nine genes regulating CDK were differentially expressed including several CDK inhibitors. The largest change was seen in p21 (CDKN1A, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A) with a 7.1-fold increase during hibernation. Three ubiquitin ligases that use p53 as a substrate were also lower during torpor (TOPORS, UBE2L6, RFWD3). Genes involved in heat shock responses and proteolysis were not significantly changed during hibernation. Only 12 of 41 heat shock proteins were differentially expressed, and all but one of these was lower during torpor by an average of threefold. Proteosome gene expression was lower for three of 46 transcripts, and only by 1.5-fold on average. Finally, all 14 differentially expressed genes out of the 84 involved in ubiquitination were lower by an average of 1.8-fold during torpor.

Fig. 8.

Cyclin genes expressed in bone marrow isolated from July, Torpor, and IBA animals (n = 6 for each condition). Error bars represent SE. The letters above each bar represent post hoc pair-wise comparisons to determine significance between collection points. Any collection point not connected by the same letter is significantly different (FDR < 0.05).

Hypothermia and hypoxia response elements.

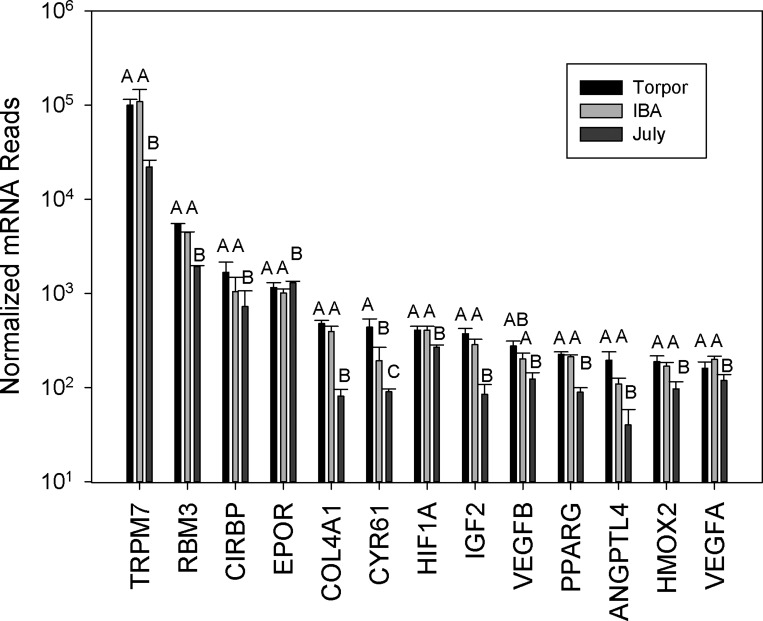

Animals in torpor have decreased oxygen consumption and are not typically hypoxic; however, as they arouse they can go through transient oxidative stress as animals rapidly increase blood flow during arousal. Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) is stabilized by hypoxic conditions and increases the expression of several genes. Of the six genes regulated by HIF detected in the transcriptome, only three (VEGFα, VEGFβ, and HMOX2) were upregulated by 1.7-fold on average while the EPO receptor showed a 1.5-fold decrease, due to the large variation in expression, numbers are graphed on a log scale (Fig. 9). During torpor, 12 HIF-independent hypoxia-responsive genes were differentially expressed, and 11 of these were an average of 2.5-fold higher relative to July animals. The most expressed of these have also been shown to be responsive to hypothermia, each displaying the following increases during hibernation, TRPM7 4.7-fold, CIRBP 2.1-fold, and RBM3 1.9-fold.

Fig. 9.

Hypoxia and hypothermia-sensitive genes expressed in bone marrow isolated from July, Torpor, and IBA animals (n = 6 for each condition). Due to the large variation in expression, numbers are graphed on a log scale. Error bars represent SE. The letters above each bar represent post hoc pair-wise comparisons to determine significance between collection points. Any collection point not connected by the same letter is significantly different (FDR < 0.05). TRPM7, transient receptor potential cation channel; RBM3, RNA binding motif; CIRBP, cold inducible RNA binding protein; EPOR, erythropoietin receptor; COLFA1, collagen, type IV, alpha 1; CYR61, cysteine-rich, angiogenic inducer; HIFIA, hypoxia inducible factor 1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; PPARG, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; ANGPTL4, angiopoietin-like 4; HMOX2, heme oxygenase 2.

DISCUSSION

There are several limitations to using a transcriptome to extrapolate to physiological changes, especially in a heterogeneous organ like bone marrow with multiple stem, structural, and energy storing cells. For example, the seasonal increase in adipocytes could lead to an increase in lipid metabolism gene transcription. Transcription (40, 94) and translation (31) slow dramatically during torpor, increasing the impact of the stability of the mRNA and proteins (34).

Immune system.

Some of the most diverse and pronounced seasonal changes observed in the ground squirrel bone marrow transcriptome were genes involved in the immune system. The most profound changes were during torpor when ground squirrels enhanced genes in the innate immune system and suppressed the expression of lymphocyte genes that would stimulate antibody mediated reactions. Among the genes involved in innate immunity, four complement genes were higher, including large increases in complement C1R, C1S, C2, and C3. This increase in bone marrow C3 mRNA is the opposite of a trend seen in hibernating golden-mantled ground squirrels, which showed a decrease in liver C3 mRNA (51). A decrease in plasma complement protein has not been consistently observed in hibernating bats or ground squirrels, but lower complement activity has been proposed as a mechanism for the decrease in T-cell stimulation of antibody production by B cells during hibernation (13, 37, 56, 60, 84). Cell-based reactions and blood flow will be slowed in torpor, limiting leukocytic exudation, and to compensate, the innate complement-based immune reaction may be enhanced. Alternatively, bone marrow-derived C3 may be serving a different function than liver-derived C3 such as promoting lipid storage (5). C5a-receptor (C5AR) is found almost exclusively on macrophages and mediates the C5a anaphylactic reaction (102). It would be hazardous for an animal in torpor to undergo an anaphylactic reaction, consistent with 4.2-fold less C5AR expression in torpor, but not IBA. Other genes involved in innate immunity that were at least twofold higher in torpor include markers for natural killer cells (ID2 and IRF8) and genes involved in leukotriene and prostaglandin synthesis (TC4S, AOAH, PTGES).

Several other genes modulating neutrophil and macrophage activity were three- to fourfold lower in torpor, but not IBA. This suggests that neutrophil and macrophage activity may be suppressed during torpor and then reactivated during an IBA. The interleukin 8 receptor (CXCR2) is found on neutrophils and inhibition of CXCR2 blocks the release of neutrophils from bone marrow. The fourfold lower CXCR2 mRNA level could contribute to the observed drop in neutrophils during torpor (26). Expression of only a few genes in granulocytes were higher during torpor, and two of them can stimulate the innate immune system. Chitinase-like protein 3 (CHI3L1) is abundant in macrophages and is involved in fighting parasitic infection, cell migration, and tissue remodeling and was 4.3-fold higher in torpor, as seen in the brain (46, 83). The toll-like receptor (TLR2) transcript was 2.3-fold higher in torpor, and it is expressed on macrophages to detect pathogens (1). In contrast TLR3, which is used to detect viruses, was 3.3-fold lower in torpor, possibly because viruses require metabolically active cells to thrive. Other macrophage-specific genes that have been shown be increased during hibernation (TLR4 and CD14) did not show differential expression, but these genes could be differentially expressed in the macrophages once they leave the bone (52, 65).

Several endothelial and leukocyte adhesion genes were higher during torpor, which may explain the sequestration of monocytes and neutrophils during torpor followed by their rapid release within 2 h of arousal. Our results in Table 4 are similar to those seen in other published studies, with the exception that lymphocyte levels did not drop as dramatically in our animals or rebound to prehibernation states. This could be due to variation in when we collected our IBA samples relative to other studies or to species differences. Vascular adhesion protein-1 (AOC3) is involved in leukocyte adhesion and T-cell homing to the thymus (41) and is made in brown adipose tissue (BAT) (36), white adipose tissue (WAT) (35), and endothelial cells. AOC3 expression was 5.5-fold higher in torpor relative to July animals and could sequester leukocytes in the bone. L selectin is the ligand for AOC3 and is found on monocytes and neutrophils but was not differentially expressed. This suggests that changes in monocytes and neutrophils adhesion during torpor may be regulated by endothelial cell expression of the AOC3 receptor or other adhesion molecules like ICAM (105). CYR61 is a cysteine-rich integrin binding receptor expressed on endothelial cells and osteoblasts, is involved in leukocyte adhesion and ECM production, and was 3.7-fold higher in torpor (28). Finally, expression of CD99 was twofold higher in torpor; CD99 is a leukocyte glycoprotein involved in cell migration, T-cell adhesion, and Ewings sarcoma tumors of the bone (72, 80). In contrast to an increase in innate immune functions, the acquired immune responses and lymphocyte activity are suppressed during torpor (9, 13, 54). During torpor CXCR4 (CD184, fusin) expression was 3.5-fold lower. This protein is highly expressed on B cells and hematopoietic stem cells that is involved in chemotaxis (23, 75, 76). Other suppressed genes showing a threefold or greater decrease include the lymphocyte surface markers and receptors LENG1, CD79B, and MS4A1.

The majority of immune system genes with higher expression in torpor were also higher in IBA, and those genes involved in the innate immune response were more likely to be higher than those involved in lymphocyte activity. This could reflect a shift to innate immunity during hibernation, which did not fluctuate with the animal's body temperature. In contrast, there was a disconnect between torpor and IBA for most genes involved in lymphocyte activity, reflecting an ability to alter lymphocyte gene expression in the short window of an IBA. Taken together, these results are consistent with a switch from an antibody and cell-mediated response when an animal has a body temperature of 37°C to an innate and complement-based response when an animal has a body temperature near 4°C. Phagocytosis and reactive oxygen species production do decrease with decreasing body temperature (98). Whether this is because cells are less active in the cold, or to avoid activating damaging macrophage or neutrophil-mediated inflammatory responses cannot be discerned from these results (73). Acquired immunity to infections is suppressed during hibernation (16, 27, 32). The switch to an innate immune response may also reflect the pathogens that a ground squirrel is most likely to encounter. For example the degree of immune activation or suppression in torpid bats is dependent on the pathogen (52, 60, 78).

Erythropoiesis.

Consistent with steady erythrocyte counts, hemoglobin concentration, and hematocrit throughout hibernation, most genes associated with erythropoiesis did not change more than twofold. The exception was a threefold increase in SF3B1 in torpor and IBA, which encodes the U2snRNP in the spliceosome. Mutations in this gene are associated with ineffective erythropoiesis and myeloproliferative disorders (18). Several genes have been shown to undergo SF3B1-dependent alternative splicing (69). Of these only four were found in the bone marrow transcriptome (NCF1, RAB3IL1, LTF, and TGFBI), and their level of expression and alternative splicing did not vary. While SF3B1 may regulate other processes in the bone marrow, higher expression could promote erythrogenesis during the short IBA periods (87). This is supported by the observation that the mean corpuscular volume of red blood cells, a measure of their size, was lower during torpor. As erythrocytes circulate through the blood stream they lose small amounts of their membrane and become smaller. Newly released reticulocytes are larger, increasing the mean volume of the erythrocytes, as seen in the IBA samples.

Megakaryocytes.

Mature megakaryocyte numbers were lower during hibernation as reported previously (87). Of the 50 differentially expressed genes in human megakaryocyte and erythroblast transcriptomes, only 12 were in the ground squirrel bone marrow transcriptome (50). Only platelet-activating factor receptor (PTAFR) was differentially expressed showing a 1.7-fold decrease in torpor relative to IBA. Matrix metallopeptidases 2 and 14 (MMP2 and MMP14) were upregulated in torpor and IBA, but these enzymes are also involved in tissue remodeling and thus may not be specific to megakaryocyte activity. Many proteins known to be involved in platelet function did not show differential expression include the surface glycoprotein receptors (GPIBA, GPIBB, GPIIB, GPIIIB) and proteins found in secretory granules (vWF, P selectin). In contrast, expression of vWF mRNA by endothelial cells in the lung was lower during torpor, suggesting a different regulatory mechanism in megakaryocytes and endothelial cells during hibernation (21). Transcription of genes in megakaryocytes does not appear to be lower during hibernation in spite of a decrease in megakaryocyte numbers. The mean platelet volume during hibernation is larger in hibernators than July animals, consistent with continued platelet synthesis, but could also be explained by an increase in red blood cell fragments or other small debris the size of platelets formed during hibernation. Newly produced reticulated platelets do not appear in the blood until 48 h postarousal (22). One possible explanation for these seemingly contradictory observations is that megakaryocytes continue to produce proteins necessary for platelet production during torpor, but that the newly synthesize platelets are only gradually released into circulation at levels below the detection of the reticulated platelet assay.

Bone strength.

Hibernators face the risk of losing bone strength during prolonged periods of inactivity. Recent studies in thirteen-lined and golden-mantled ground squirrels, marmots, and woodchucks have shown that some microstructural bone loss occurs during hibernation but macrostructural strength is maintained (24, 55, 92, 100). During hibernation, the osteocyte lacunar porosity increases, indicating a decrease in cell number. One possible explanation for maintaining bone strength with a decrease in cell number is higher expression of matrix remodeling and ECM proteins. Collagen 4A2 was highly expressed and showed a 5.4-fold increase in expression during hibernation. Collagen 4A2 is abundant in bone ECM, and its loss leads to lack of bone remodeling and osteoporosis (39, 43). Melanoma cell adhesion molecule (MCAM, CD146) was 3.7-fold higher in torpor and is involved in cell adhesion to the ECM (7). Transcription of these ECM genes are higher in both torpor and IBA, consistent with a longer-term response to extracellular strengthening of bone during hibernation instead of a temperature-dependent change. Histological sections did not reveal gross changes in collagen deposition in the shaft or head of the femur. The most striking differences were at the ends of the femur where proteoglycan deposition increased during hibernation. This process began during October entry into hibernation and resolved within a week postarousal in March. Most mammals show a loss of glycosaminoglycan and disorganization of cartilage after immobilization (95, 106). The joints of hibernators may have adaptations to preserve joint cartilage during immobilization similar to those preserving bone strength. No changes were observed in genes known to regulate osteoblast growth or differentiation into osteocytes, again consistent with the histological analysis of the bone structure showing larger lacunar size (55). Unlike bears, which hibernate for months without excreting waste, ground squirrels are able to urinate during IBA events. It was speculated that secreted acid phosphatase activity may increase to control calcium loss during these times (55); however, a decrease in soluble acid phosphatase (ACP2) transcription was observed during hibernation in ground squirrels.

Cell cycle genes.

Regulation of cell cycle checkpoints typically involves a constitutively expressed CDK being activated by a transiently expressed cyclin. The majority of CDK were not differentially expressed in the three stages examined. In contrast, in the torpid ground squirrel there was an overall reduction in cyclin expression, with cyclins A2 and F at 80 and 30% of the July levels, respectively. Mouse hematopoietic stem cells show differential expression of cyclin genes, with cyclins A2 and F four- and fivefold higher (74). The lower expression of cyclins A2 and F would be consistent with a general suppression of hematopoiesis during hibernation. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 inhibits the cell cycle at the G1/S checkpoint and is increased in hibernation. Three other ubiquitin ligases (TOPORS, UBE2L6, RFWD3) that use p53 as a substrate showed lower expression during torpor. Thus it is plausible that decreased p53 ubiquitination leads to increased p53-regulated transcription of p21 and arrest of the cell cycle in bone marrow during hibernation. A similar process has been reported in golden-mantled ground squirrel livers during torpor and IBA (68).

Protein turnover.

Hibernation produces rapid changes in body temperature and oxidative stress during reperfusion (17, 67). Damaged cellular proteins can be repaired by chaperone and heat shock proteins or ubiquitinated and hydrolyzed by the proteasome. The genes in these pathways were lower in hibernation, similar to the trend in arctic ground squirrel liver (104), skeletal muscle (96, 103), and gut (93). In the brain, the hypothalamus remains active and shows an increase in ubiquitin ligases compared with the less active cerebral cortex (83). While expression of HIF-dependent genes were not higher in either hibernation state, several markers of hypothermia and HIF-independent hypoxia responses were higher. The largest fold change, and most abundantly expressed gene, was the transient receptor potential cation channel M7 (TRPM7). This gene is ubiquitously expressed and is greatest in heart, pituitary gland, bone, and adipose tissue (70, 83). In the bone TRPM7 may be regulating extracellular calcium and magnesium, responding to ischemic reperfusion, or regulating osteogenesis (20, 57, 70). TRPM7 is also abundant in WAT, but the level of expression in bone marrow greatly exceeds that seen in adipocytes, so this is not likely due to the increase in adipocytes alone (35).

When cultured mammalian cells are subjected to moderate hypothermia (25–32°C), 100 genes were upregulated, and 67 were downregulated (85). In comparing this study with ground squirrel bone marrow, heat shock proteins were also downregulated, while only a few upregulated genes were observed. The exceptions were insulin-like growth factor-2 (3-fold increase in hibernation), and two cold and hypoxia-responsive proteins, cold-inducible RNA binding protein (CIRBP) and RNA binding motif protein 3 (RBM3). These cold-shock proteins increase general translation during hibernation in bears and hamsters (30, 71) and are responsive to hypoxia in an HIF-independent manner (97). Both bind to mRNA altering posttranscriptional expression of specific mRNAs in the cold by promoting alternative splicing, mRNA stability, and allowing translation to begin at internal ribosome entry sites (IRES) (48, 59). Cells overexpressing CIRBP arrest in G1, which could inhibit hematopoiesis during torpor (63). Finally, CIRBP is induced by ketogenic diet and fasting, which mirrors the metabolic state of ground squirrels during hibernation (66). CIRBP can regulate circadian rhythm in cultured NIH3T3 cells by binding to RNAs encoding SIRT1, CLOCK, RORα, PER3, and NCOR1 (61). In arctic ground squirrel liver several CIRBP target genes were differentially expressed, including: DERL2, FUBP1, NNT, SMAD5, TARDBP, and THRA (104). Of these genes, only NNT and TARDBP were differentially regulated in the ground squirrel bone marrow transcriptome, and they were lower, suggesting CIRBP does not regulate circadian rhythm in the bone marrow. The increase in bone marrow CIRBP during torpor is not likely due to increases in adipocytes as bone marrow expression during torpor is greater than in any other tissue studied (35, 36, 83).

Bone marrow adipocytes.

Twenty-two genes highly expressed in WAT showed increases during hibernation (torpor and IBA) relative to July animals. This could be explained by the observed increase in adipocytes during torpor as none of the expression levels in bone marrow exceeded published levels seen in WAT. The accumulation of adipocytes could be for energy storage during hibernation or be negative regulators of hematopoiesis (62) and osteoblast activity (42). Bone marrow adipocytes in mice show differential gene expression compared with epididymal adipocytes (47, 82). In examination of the 14 genes reported to increase in mouse bone marrow adipose, only one was higher during hibernation in squirrels (oncostatin M) with the remainder showing no change or decreasing during hibernation. Of the 18 genes reported to decrease in mouse bone marrow adipose, only one was lower during hibernation in squirrels (plasminogen activator inhibitor 1), again with the remainder showing no change or increasing during hibernation. Neuronatin (NNAT) is expressed in the hypothalamus and both brown and white adipose, and this gene showed the largest increase (14-fold) during torpor in hibernating ground squirrels. Inhibition of neuronatin by RNAi caused white adipose primary cultures to take on the characteristics of brown adipose including increased mitochondrial biogenesis (33). While neurotropin levels were not higher in WAT, expression was significantly lower in BAT in hibernating ground squirrels. The increase in bone marrow adipose could originate from differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells into adipocytes instead of osteoblasts through adipogenesis (47). In humans and other nonhibernating mammals (82), bone marrow adipose increases with age and is not seasonally reversed as seen in the ground squirrel bone marrow sections in this study. The gene expression and histological appearance of the adipocytes in the bone marrow correlate better with WAT (35) than BAT (36) or bone marrow adipose (82).

Conclusions

Mammalian hibernation results in many physiological adaptations, especially evident in a tissue comprising multiple diverse cell types like bone marrow. During hibernation the expression of immune system genes switched from a cell-mediated acquired immune response to an innate complement-based response. This could be explained by lower leukocyte numbers or activity during torpor, or that complement may cause less collateral damage than inflammation triggered by granulocytes. Genes necessary for erythrocyte production were maintained at euthermic levels of expression, consistent with no change in erythrocyte numbers and the need for oxygen delivery during torpor. Megakaryocyte genes were also not differentially expressed, even though circulating platelets did show dramatic fluctuations between torpid and aroused animals. This suggests that platelets produced during hibernation may not have different genes expressed than those produced in July and the ability to be sequestered during torpor is an intrinsic property in the ground squirrel platelets. Osteoblast and osteocyte genes were not differentially expressed, while genes for ECM were higher consistent with the maintenance of bone strength in spite of bone cell loss during hibernation. Transcription of heat shock and proteolytic genes were not differentially expressed during hibernation, but instead HIF-independent hypoxia and hypothermia-responsive gene expression was higher, consistent with the lower body temperature during torpor. This global view of the changes in the bone marrow transcriptome over both short term (torpor vs. IBA) and long term (torpor vs. July) is supported by variations in the levels of circulating blood cells, more adipocytes in bone marrow, and maintenance of bone strength during hibernation. Limitations of this study include not being able to discern differential gene expression within a cell type from changes in the abundance of the cell type, and monitoring all downstream effects of the hundreds of changes in protein expression suggested by the differential mRNA expression. Given these limitations, this study raises questions regarding gene regulation of these processes, impact on immune function, and stem cell activity during torpor that should be valuable to guide multiple future avenues of research.

GRANTS

Office of Extramural Research, National Institutes of Health: S. T. Cooper 2R15HL093680-02; University of Minnesota Institute Transdisciplinary Fellowship: M. Hampton; University of Minnesota McKnight Presidential Endowment Fund: M. T. Andrews.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.T.C., S.S.S., M.F., K.W., D.R.H., H.B., S.E.C., M.T.A., and M.H. conception and design of research; S.T.C., S.S.S., M.F., K.W., H.B., E.C., and S.E.C. performed experiments; S.T.C., S.S.S., M.F., K.W., D.R.H., H.B., E.C., M.T.A., and M.H. analyzed data; S.T.C., S.S.S., M.F., K.W., D.R.H., H.B., E.C., S.E.C., M.T.A., and M.H. interpreted results of experiments; S.T.C., M.F., K.W., D.R.H., H.B., E.C., and M.H. prepared figures; S.T.C., M.T.A., and M.H. drafted manuscript; S.T.C., S.S.S., M.T.A., and M.H. edited and revised manuscript; S.T.C., S.S.S., M.F., K.W., D.R.H., H.B., E.C., S.E.C., M.T.A., and M.H. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 4: 499–511, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol 11: R106, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews MT. Advances in molecular biology of hibernation in mammals. Bioessays 29: 431–40, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrews MT, Russeth KP, Drewes LR, Henry PG. Adaptive mechanisms regulate preferred utilization of ketones in the heart and brain of a hibernating mammal during arousal from torpor. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R383–R393, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbu A, Hamad OA, Lind L, Ekdahl KN, Nilsson B. The role of complement factor C3 in lipid metabolism. Mol Immunol 67: 101–107, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B 57: 289–300, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bianco P, Sacchetti B, Riminucci M. Osteoprogenitors and the hematopoietic microenvironment. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 24: 37–47, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohr M, Brooks AR, Kurtz CC. Hibernation induces immune changes in the lung of 13-lined ground squirrels (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus). Dev Comp Immunol 47: 178–184, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouma HR, Carey HV, Kroese FG. Hibernation: the immune system at rest? J Leukoc Biol 88: 619–624, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouma HR, Strijkstra AM, Boerema AS, Deelman LE, Epema AH, Hut RA, Kroese FG, Henning RH. Blood cell dynamics during hibernation in the European Ground Squirrel. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 136: 319–323, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouma HR, Kroese FG, Kok JW, Talaei F, Boerema AS, Herwig A, Draghiciu O, van Buiten A, Epema AH, van Dam A, Strijkstra AM, Henning RH. Low body temperature governs the decline of circulating lymphocytes during hibernation through sphingosine-1-phosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 2052–2057, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouma HR, Dugbartey GJ, Boerema AS, Talaei F, Herwig A, Goris M, van Buiten A, Strijkstra AM, Carey HV, Henning RH, Kroese FG. Reduction of body temperature governs neutrophil retention in hibernating and nonhibernating animals by margination. J Leukoc Biol 94: 431–437, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouma HR, Henning RH, Kroese FGM, Carey HV. Hibernation is associated with depression of T-cell independent humoral immune responses in the 13-lined ground squirrel. Dev Comp Immunol 39: 154–160, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brace KC. Histological changes in the tissues of the hibernating marmot following whole body irradiation. Science 116: 570–571, 1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burton RS, Reichman OJ. Does immune challenge affect torpor duration? Funct Ecol 13: 232–237, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cahill JE, Lewert RM, Jaroslow BN. Effect of hibernation on course of infection and immune response in Citellus tridecemlineatus infected with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. J Parasitol 53: 110–115, 1967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carey HV, Frank CL, Seifert JP. Hibernation induces oxidative stress and activation of NK-kappaB in ground squirrel intestine. J Comp Physiol B 170: 551–559, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cazzola M, Rossi M, Malcovati L, Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro Gruppo Italiano Malattie. Biologic and clinical significance of somatic mutations of SF3B1 in myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 121: 260–269, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen XD, Dusevich V, Feng JQ, Manolagas SC, Jilka RL. Extracellular matrix made by bone marrow cells facilitates expansion of marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells and prevents their differentiation into osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res 22: 1943–1956, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng H, Feng JM, Figueiredo ML, Zhang H, Nelson PL, Marigo V, Beck A. Transient receptor potential melastatin type 7 channel is critical for the survival of bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 19: 1393–1403, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper S, Sell S, Nelson L, Hawes J, Benrud JA, Kohlnhofer BM, Burmeister BR, Flood VH. Von Willebrand factor is reversibly decreased during torpor in 13-lined ground squirrels. J Comp Physiol B 186: 131–139, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper ST, Richters KE, Melin TE, Liu ZJ, Hordyk PJ, Benrud RR, Geiser LR, Cash SE, Simon Shelley C, Howard DR, Ereth MH, Sola-Visner MC. The hibernating 13-lined ground squirrel as a model organism for potential cold storage of platelets. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 302: R1202–R1208, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Decaillot FM, Kazmi MA, Lin Y, Ray-Saha S, Sakmar TP, Sachdev P. CXCR7/CXCR4 heterodimer constitutively recruits beta-arrestin to enhance cell migration. J Biol Chem 286: 32188–32197, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doherty AH, Frampton JD, Vinyard CJ. Hibernation does not reduce cortical bone density, area or second moments of inertia in woodchucks (Marmota monax). J Morphol 273: 604–617, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dritschilo A, Sherman DS. Radiation and chemical injury in the bone marrow. Environ Health Perspect 39: 59–64, 1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eash KJ, Greenbaum AM, Gopalan PK, Link DC. CXCR2 and CXCR4 antagonistically regulate neutrophil trafficking from murine bone marrow. J Clin Invest 120: 2423–2431, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emmons RW. Colorado tick fever: prolonged viremia in hibernating Citellus lateralis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 15: 428–433, 1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emre Y, Imhof BA. Matricellular protein CCN1/CYR61: a new player in inflammation and leukocyte trafficking. Semin Immunopathol 36: 253–259, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erlacher M, Strahm B. Missing cells: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of (pan)cytopenia in childhood. Front Pediatr 3: 64, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fedorov VB, Goropashnaya AV, Tøien O, Stewart NC, Chang C, Wang H, Yan J, Showe LC, Showe MK, Barnes BM. Modulation of gene expression in heart and liver of hibernating black bears (Ursus americanus). BMC Genomics 12: 171, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frerichs KU, Smith CB, Brenner M, DeGracia DJ, Krause GS, Marrone L, Dever TE, Hallenbeck JM. Suppression of protein synthesis in brain during hibernation involves inhibition of protein initiation and elongation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 14511–14516, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galletti G, Cavicchi G, Ussia G. Replication of Mycobacterium leprae in hibernating ground squirrels (Citellus tridecemlineatus). Acta Leprol Jul-Sep: 23–31, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gburcik V, Cleasby ME, Timmons JA. Loss of neuronatin promotes “browning” of primary mouse adipocytes while reducing Glut1-mediated glucose disposal. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 304: E885–E894, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grabek KR, Diniz Behn C, Barsh GS, Hesselberth JR, Martin SL. Enhanced stability and polyadenylation of select mRNAs support rapid thermogenesis in the brown fat of a hibernator. Elife 4, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hampton M, Melvin RG, Kendall AH, Kirkpatrick BR, Peterson N, Andrews MT. Deep sequencing the transcriptome reveals seasonal adaptive mechanisms in a hibernating mammal. PLoS One 6: e27021, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hampton M, Melvin RG, Andrews MT. Transcriptomic analysis of brown adipose tissue across the physiological extremes of natural hibernation. PLoS One 8: e85157, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hecht AM, Braun BC, Krause E, Voigt CC, Greenwood AD, Czirják GÁ. Plasma proteomic analysis of active and torpid greater mouse-eared bats (Myotis myotis). Sci Rep 5: 16604, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoff P, Belavý DL, Huscher D, Lang A, Hahne M, Kuhlmey AK, Maschmeyer P, Armbrecht G, Fitzner R, Perschel FH, Gaber T, Burmester GR, Straub RH, Felsenberg D, Buttgereit F. Effects of 60-day bed rest with and without exercise on cellular and humoral immunological parameters. Cell Mol Immunol 12: 483–492, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hopwood B, Tsykin A, Findlay DM, Fazzalari NL. Microarray gene expression profiling of osteoarthritic bone suggests altered bone remodelling, WNT and transforming growth factor-beta/bone morphogenic protein signalling. Arthritis Res Ther 9: R100, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knight JE, Narus EN, Martin SL, Jacobson A, Barnes BM, Boyer BB. mRNA stability and polysome loss in hibernating Arctic ground squirrels (Spermophilus parryii). Mol Cell Biol 20: 6374–6379, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koc-Zorawska E, Przybylowski P, Malyszko JS, Mysliwiec M, Malyszko J. Vascular adhesion protein-1, a novel molecule, in kidney and heart allograft recipients. Transplant Proc 45: 2009–2012, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kostenuik PJ, Halloran BP, Morey-Holton ER, Bikle DD. Skeletal unloading inhibits the in vitro proliferation and differentiation of rat osteoprogenitor cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 273: E1133–E1139, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuo DS, Labelle-Dumais C, Gould DB. COL4A1 and COL4A2 mutations and disease: insights into pathogenic mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Hum Mol Genet 21: R97–R110, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kurtz CC, Carey HV. Seasonal changes in the intestinal immune system of hibernating ground squirrels. Dev Comp Immunol 31: 415–428, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.LeBlanc AD, Spector ER, Evans HJ, Sibonga JD. Skeletal responses to space flight and the bed rest analog: a review. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 7: 33–47, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee CG, Da Silva CA, Dela Cruz CS, Ahangari F, Ma B, Kang MJ, He CH, Takyar S, Elias JA. Role of chitin and chitinase/chitinase-like proteins in inflammation, tissue remodeling, and injury. Annu Rev Physiol 73: 479–501, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu LF, Shen WJ, Ueno M, Patel S, Kraemer FB. Characterization of age-related gene expression profiling in bone marrow and epididymal adipocytes. BMC Genomics 12: 1–18, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lleonart ME. A new generation of proto-oncogenes: cold-inducible RNA binding proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1805: 43–52, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ma YL, Zhu X, Rivera PM, Toien O, Barnes BM, LaManna JC, Smith MA, Drew KL. Absence of cellular stress in brain after hypoxia induced by arousal from hibernation in Arctic ground squirrels. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R1297–R1306, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Macaulay IC, Tijssen MR, Thijssen-Timmer DC, Gusnanto A, Steward M, Burns P, Langford CF, Ellis PD, Dudbridge F, Zwaginga JJ, Watkins NA, van der Schoot CE, Ouwehand WH. Comparative gene expression profiling of in vitro differentiated megakaryocytes and erythroblasts identifies novel activatory and inhibitory platelet membrane proteins. Blood 109: 3260–3269, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maniero GD. Classical pathway serum complement activity throughout various stages of the annual cycle of a mammalian hibernator, the golden-mantled ground squirrel, Spermophilus lateralis. Dev Comp Immunol 26: 563–574, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maniero GD. Ground squirrel splenic macrophages bind lipopolysaccharide over a wide range of temperatures at all phases of their annual hibernation cycle. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 28: 297–309, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marenzana M, T Arnett R. The key role of the blood supply to bone. Bone Res 1: 203–215, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin LB, Weil ZM, Nelson RJ. Seasonal changes in vertebrate immune activity: mediation by physiological trade-offs. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 363: 321–339, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McGee-Lawrence ME, Stoll DM, Mantila ER, Fahrner BK, Carey HV, Donahue SW. Thirteen-lined ground squirrels (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus) show microstructural bone loss during hibernation but preserve bone macrostructural geometry and strength. J Exp Biol 214: 1240–1247, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McKenna JM, Musacchia XJ. Antibody formation in hibernating ground squirrels (Citrellus tridecemlineatus). Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 129: 720–724, 1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mene P, Punzo G, Pirozzi N. TRP channels as therapeutic targets in kidney disease and hypertension. Curr Top Med Chem 13: 386–397, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Minaire P, Edouard C, Arlot M, Meunier PJ. Marrow changes in paraplegic patients. Calcif Tissue Int 36: 338–340, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mitchell SA, Spriggs KA, Bushell M, Evans JR, Stoneley M, Le Quesne JP, Spriggs RV, Willis AE. Identification of a motif that mediates polypyrimidine tract-binding protein-dependent internal ribosome entry. Genes Dev 19: 1556–1571, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moore MS, Reichard JD, Murtha TD, Zahedi B, Fallier RM, Kunz TH. Specific alterations in complement protein activity of little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus) hibernating in white-nose syndrome affected sites. PLoS One 6: e27430, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morf J, Rey G, Schneider K, Stratmann M, Fujita J, Naef F, Schibler U. Cold-inducible RNA-binding protein modulates circadian gene expression posttranscriptionally. Science 338: 379–383, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Naveiras O, Nardi V, Wenzel PL, Hauschka PV, Fahey F, Daley GQ. Bone-marrow adipocytes as negative regulators of the haematopoietic microenvironment. Nature 460: 259–263, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neutelings T, Lambert CA, Nusgens BV, Colige AC. Effects of mild cold shock (25 degrees C) followed by warming up at 37 degrees C on the cellular stress response. PLoS One 8: e69687, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nombela-Arrieta C, Ritz J, Silberstein LE. The elusive nature and function of mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12: 126–131, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Novoselova EG, Kolaeva SG, Makar VR, Agaphonova TA. Production of tumor necrosis factor in cells of hibernating ground squirrels Citellus undulatus during annual cycle. Life Sci 67: 1073–1080, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oishi K, Yamamoto S, Uchida D, Doi R. Ketogenic diet and fasting induce the expression of cold-inducible RNA-binding protein with time-dependent hypothermia in the mouse liver. FEBS Open Bio 3: 192–195, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Orr AL, Lohse LA, Drew KL, Hermes-Lima M. Physiological oxidative stress after arousal from hibernation in Arctic ground squirrel. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 153: 213–221, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pan P, Treat MD, van Breukelen F. A systems-level approach to understanding transcriptional regulation by p53 during mammalian hibernation. J Exp Biol 217: 2489–2498, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Papaemmanuil E, Cazzola M, Boultwood J, Malcovati L, Vyas P, Bowen D, Pellagatti A, Wainscoat JS, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Godfrey AL, Rapado I, Cvejic A, Rance R, McGee C, Ellis P, Mudie LJ, Stephens PJ, McLaren S, Massie CE, Tarpey PS, Varela I, Nik-Zainal S, Davies HR, Shlien A, Jones D, Raine K, Hinton J, Butler AP, Teague JW, Baxter EJ, Score J, Galli A, Della Porta MG, Travaglino E, Groves M, Tauro S, Munshi NC, Anderson KC, El-Naggar A, Fischer A, Mustonen V, Warren AJ, Cross NC, Green AR, Futreal PA, Stratton MR, Campbell PJ, Chronic Myeloid Disorders Working Group of the International Cancer Genome. Somatic SF3B1 mutation in myelodysplasia with ring sideroblasts. N Engl J Med 365: 1384–1395, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Park HS, Hong C, Kim BJ, So I. The pathophysiologic roles of TRPM7 channel. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol 18: 15–23, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peretti D, Bastide A, Radford H, Verity N, Molloy C, Martin MG, Moreno JA, Steinert JR, Smith T, Dinsdale D, Willis AE, Mallucci GR. RBM3 mediates structural plasticity and protective effects of cooling in neurodegeneration. Nature 518: 236–239, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Petri B, Bixel MG. Molecular events during leukocyte diapedesis. FEBS J 273: 4399–4407, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Prendergast BJ, Freeman DA, Zucker I, Nelson RJ. Periodic arousal from hibernation is necessary for initiation of immune responses in ground squirrels. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282: R1054–R1062, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Quesenberry PJ, Dooner GJ, Tatto MD, Colvin GA, Johnson K, Dooner MS. Expression of cell cycle-related genes with cytokine-induced cell cycle progression of primitive hematopoietic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 19: 453–460, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ratajczak MZ, Kim C, Janowska-Wieczorek A, Ratajczak J. The expanding family of bone marrow homing factors for hematopoietic stem cells: stromal derived factor 1 is not the only player in the game. Sci World J 2012: 758512, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ratajczak MZ, Kim C, Wu W, Shin DM, Bryndza E, Kucia M, Ratajczak J. The role of innate immunity in trafficking of hematopoietic stem cells-an emerging link between activation of complement cascade and chemotactic gradients of bioactive sphingolipids. Adv Exp Med Biol 946: 37–54, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reddick RL, Poole BL, Penick GD. Thrombocytopenia of hibernation. Mechanism of induction and recovery. Lab Invest 28: 270–278, 1973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Reeder DM, Frank CL, Turner GG, Meteyer CU, Kurta A, Britzke ER, Vodzak ME, Darling SR, Stihler CW, Hicks AC, Jacob R, Grieneisen LE, Brownlee SA, Muller LK, Blehert DS. Frequent arousal from hibernation linked to severity of infection and mortality in bats with white-nose syndrome. PLoS One 7: e38920, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reznik G, Reznik-Schuller H, Emminger A, Mohr U. Comparative studies of blood from hibernating and nonhibernating European hamsters (Cricetus cricetus L). Lab Anim Sci 25: 210–215, 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rocchi A, Manara MC, Sciandra M, Zambelli D, Nardi F, Nicoletti G, Garofalo C, Meschini S, Astolfi A, Colombo MP, Lessnick SL, Picci P, Scotlandi K. CD99 inhibits neural differentiation of human Ewing sarcoma cells and thereby contributes to oncogenesis. J Clin Invest 120: 668–680, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sahdo B, Evans AL, Arnemo JM, Fröbert O, Särndahl E, Blanc S. Body temperature during hibernation is highly correlated with a decrease in circulating innate immune cells in the brown bear (Ursus arctos): a common feature among hibernators? Int J Med Sci 10: 508–514, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Scheller EL, Rosen CJ. What's the matter with MAT? Marrow adipose tissue, metabolism, and skeletal health. Ann NY Acad Sci 1311: 14–30, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schwartz C, Hampton M, Andrews MT. Seasonal and regional differences in gene expression in the brain of a hibernating mammal. PLoS One 8: e58427, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sidky YA, Hayward JS, Ruth RF. Seasonal variations of the immune response of ground squirrels kept at 22–24 degrees C. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 50: 203–206, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sonna LA, Kuhlmeier MM, Carter HC, Hasday JD, Lilly CM, Fairchild KD. Effect of moderate hypothermia on gene expression by THP-1 cells: a DNA microarray study. Physiol Genomics 26: 91–98, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sun S, Henriksen K, Karsdal MA, Byrjalsen I, Rittweger J, Armbrecht G, Belavy DL, Felsenberg D, Nedergaard AF. Collagen type III and VI turnover in response to long-term immobilization. PLoS One 10: e0144525, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Szilagyi JE, Senturia JB. A comparison of bone marrow leukocytes in hibernating and nonhibernating woodchucks and ground squirrels. Cryobiology 9: 257–261, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.The Gene Ontology Consortium. Gene Ontology Consortium: going forward. Nucleic Acids Research 43: D1049–D1056, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Toien O, Drew KL, Chao ML, Rice ME. Ascorbate dynamics and oxygen consumption during arousal from hibernation in Arctic ground squirrels. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R572–R583, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tokutomi T, Miyagi T, Morimoto K, Karukaya T, Shigemori M. Effect of hypothermia on serum electrolyte, inflammation, coagulation, and nutritional parameters in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care 1: 171–182, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Trudel G, Payne M, Madler B, Ramachandran N, Lecompte M, Wade C, Biolo G, Blanc S, Hughson R, Bear L, Uhthoff HK. Bone marrow fat accumulation after 60 days of bed rest persisted 1 year after activities were resumed along with hemopoietic stimulation: the Women International Space Simulation for Exploration study. J Appl Physiol (1985) 107: 540–548, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Utz JC, Nelson S, O'Toole BJ, van Breukelen F. Bone strength is maintained after 8 months of inactivity in hibernating golden-mantled ground squirrels, Spermophilus lateralis. J Exp Biol 212: 2746–2752, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.van Breukelen F, Carey V. Ubiquitin conjugate dynamics in the gut and liver of hibernating ground squirrels. J Comp Physiol B 172: 269–273, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.van Breukelen F, Martin SL. Reversible depression of transcription during hibernation. J Comp Physiol B 172: 355–361, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vanwanseele B, Lucchinetti E, Stüssi E. The effects of immobilization on the characteristics of articular cartilage: current concepts and future directions. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 10: 408–419, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]