Abstract

Aquaporin-2 (AQP2) is regulated in part via vasopressin-mediated changes in protein half-life that are in turn dependent on AQP2 ubiquitination. Here we addressed the question, “What E3 ubiquitin ligase is most likely to be responsible for AQP2 ubiquitination?” using large-scale data integration based on Bayes' rule. The first step was to bioinformatically identify all E3 ligase genes coded by the human genome. The 377 E3 ubiquitin ligases identified in the human genome, consisting predominant of HECT, RING, and U-box proteins, have been used to create a publically accessible and downloadable online database (https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/E3-ligases/). We also curated a second database of E3 ligase accessory proteins that included BTB domain proteins, cullins, SOCS-box proteins, and F-box proteins. Using Bayes' theorem to integrate information from multiple large-scale proteomic and transcriptomic datasets, we ranked these 377 E3 ligases with respect to their probability of interaction with AQP2. Application of Bayes' rule identified the E3 ligases most likely to interact with AQP2 as (in order of probability): NEDD4 and NEDD4L (tied for first), AMFR, STUB1, ITCH, ZFPL1. Significantly, the two E3 ligases tied for top rank have also been studied extensively in the reductionist literature as regulatory proteins in renal tubule epithelia. The concordance of conclusions from reductionist and systems-level data provides strong motivation for further studies of the roles of NEDD4 and NEDD4L in the regulation of AQP2 protein turnover.

Keywords: aquaporin-2, E3 ubiquitin ligases, collecting duct, kidney

aquaporin-2 (aqp2) is a molecular water channel that carries water molecules across the apical plasma membrane of renal collecting duct cells and is a target for regulation by the peptide hormone, vasopressin (23). AQP2 is known to be regulated by vasopressin in at least two ways: 1) by controlling trafficking of AQP2-containing membrane vesicles to and from the plasma membrane (21) and 2) by controlling the total abundance of the AQP2 protein in each principal cell (22).

The abundance of AQP2 in each cell is determined by a balance between its production (translation) and degradation. Multiple prior studies have supplied evidence that AQP2 production is regulated in collecting duct principal cells through transcriptional mechanisms that ultimately change the rate of AQP2 translation by increasing the amount of AQP2 mRNA (7, 9). More recent studies have shown that the rate of degradation of the AQP2 protein is regulated by vasopressin as well (20, 24). Specifically, the half-life of the AQP2 protein appears to be prolonged by vasopressin, contributing to its increase in abundance (24). Protein half-life is regulated in part through ubiquitination. Ubiquitination is the process by which ubiquitin is covalently attached to proteins via linkage to lysine side chains. AQP2 is known to be ubiquitinated at Lysine-270 in its COOH-terminal tail (13). Ubiquitination has several regulatory roles in cells, but a major one is selection for degradation via either the proteasome or the lysosome (19). Typically, ubiquitin ligases are classified as RING, HECT, or U-box domain-containing proteins (1). The E3 ligase that ubiquitinates AQP2 has not been definitively identified, although siRNA knockdowns of the E3 ligase Nedd4 (and the E3 ligase regulator cullin-5) reduced the rate of AQP2 degradation in a vasopressin-responsive cultured mouse collecting duct cell line called mpkCCD cells (16).

The first goal of the present paper is to create a list of all E3 ubiquitin ligases present in mammalian genomes. Members of this list could be considered candidates for a role in ubiquitination of AQP2. We found several partial lists of E3 ligases (3, 6, 12, 18), but no single published comprehensive list of E3 ligases present in the human genome. Therefore, an initial step was to combine information from multiple sources to construct such a list. Because of the potential usefulness of this list to other investigators, we created an online webpage with the information (See URL: https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/). There are also a number of E3 ligase interacting proteins, including Cullins, BTB proteins, SOCS box proteins, and F-box proteins, that could play a role in AQP2 ubiquitination. We have separately curated a consolidated list of those proteins.

The second goal, once we compiled the list of all mammalian E3 ligases, was to identify which of the E3 ligases are most likely to ubiquitinate AQP2 using Bayes' theorem to integrate data from multiple sources (2).

METHODS

We assembled a Database of Human E3 Ubiquitin Ligases (https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/E3-ligases/) using several bioinformatic tools as follows. We collated an initial list from several preexisting resources, viz. the Cell Signaling Incorporated Database (http://www.cellsignal.com/common/content/content.jsp?id=science-tables-ubiquitin), the hUbiqutome database (6) (http://bioinfo.bjmu.edu.cn/hubi/), the Qiagen Ubiquitin Ligases PCR Array dataset (http://www.sabiosciences.com/rt_pcr_product/HTML/PAHS-3079Z.html), the UbiProt Database (3) (http://ubiprot.org.ru/), DUDE v. 1.0 (http://www.dude-db.org/) (12), and Supplemental Table S1 of Li et al. (18). Official gene symbols were assigned using the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) search tool (http://www.genenames.org/cgi-bin/search). Gene Ontology terms were found for all proteins on the list using ABE (Automated Bioinformatics Extractor, http://helixweb.nih.gov/ESBL/ABE/) (30); proteins that did not map to the terms containing the string “ubiquit” were removed from the master list. The ABE mapping identified some as pseudogenes, which were also removed from the list. A domain search was executed using ABE on the list of remaining proteins, seeking to identify RING, HECT, or U-box domains or their variants (1). The proteins that contained any of these domains were automatically put on the master list of E3 ubiquitin ligases, while proteins that did not contain these domains were analyzed further as follows. Any protein whose RefSeq protein name contains “E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase” was also added to the master list, despite the absence of an annotated RING, HECT, or U-box domain. An example is the three Pellino family proteins (Peli1, Peli2, and Peli3). Proteins not on the master list but noted in the UniProt record to be part of an ubiquitin E3 ligase complex were placed in a separate Database of Human E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Accessory Proteins (https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/E3-ligases/RelatedProteins.html). This list includes cullins, BTB proteins, F-box proteins, and SOCS box proteins. We also ran a search across the entire human genome for RING, HECT, or U-box domains using ABE and cross-referenced this list with the master list previously mentioned. (This includes proteins that can function as SUMO and Nedd8 E3 ligases as well as ubiquitin ligases.)

Bayesian analysis.

To determine the E3 ubiquitin ligase most likely to ubiquitinate AQP2, we used Bayes' rule to rank the E3 ligases (2). Bayes' rule can be written P(A|B) = P(B|A)P(A)/P(B), where P(A|B) is the probability of A given B, P(B|A) is the probability of B given A, P(A) is the prior probability for A, and P(B) is the sum of probabilities of B over all A (5). Here, we use probabilities to numerically encode our uncertainty about whether a particular E3 ligase ubiquitinates AQP2. In general, probabilities can range between 0 and 1 with 0 indicating certainty that a particular ubiquitin ligase is not involved in ubiquitinating AQP2, and 1 indicating certainty that that particular ubiquitin ligase is involved in ubiquitinating AQP2. For instance, if A stands for the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4, then P(A) = 0.7 indicates that it is more probable than not that Nedd4 ubiquitinates AQP2. The probability designated by P(A|B) is interpreted as the uncertainty that a particular ligase, A, ubiquitinates AQP2 in light of additional evidence, B. For instance, B could stand for colocalization of the ligase A in the same subcellular fraction as AQP2.

Bayes' rule allows us to compute P(A|B) given three pieces of information. P(A) is our uncertainty in A when we do not take into account any additional information. P(B|A), sometimes referred to as the likelihood, is the probability of observing some data B under the assumption that ligase A ubiquitinates AQP2. The last probabilistic input is P(B) and measures whether B is to be expected, irrespective of whether A ubiquitinates AQP2. P(B) is computed by summing P(B|A)P(A) over all the ligases.

We started with all 377 E3 ubiquitin ligases, assigning them the same prior probability P(A) of 1/377. The datasets used were: 1) the mouse mpkCCD transcriptome identified using Affymetrix expression microarrays, as reported by Yu et al. (33) and downloaded from http://esbl.nhlbi.nih.gov/mpkCCD-transcriptome/; 2) the mouse mpkCCD proteome (32), using proteins downloaded from https://helixweb.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/mpkCCD_Protein_Abundances/; 3) calculated dot product of E3 ubiquitin ligase with AQP2 in mouse mpkCCD subcellular fractions (11, 32) downloaded from https://helixweb.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/mpkFractions/; 4) rat RNA-seq transcriptomic analysis of microdissected rat collecting duct segments (15) downloaded from https://helixweb.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/NephronRNAseq/All_transcripts.html; 5) Gene Ontology terms, found using ABE (30), to determine where each of the E3 ligase proteins are found within the cell; and 6) a list of E3 ligases annotated in UniProt as having at least one “Transmembrane Region” or a binding domain (C2, Clathrin, FERM, PDZ, SH2, or WW) that interacts with integral membrane proteins.

We illustrate how the likelihoods, P(B|A), were assigned by considering the first dataset. Here, B stands for a transcript identified in the microarray experiments, while A stands for the particular ligase, P(B|A) indicating the probability that the transcript for A would be detected at elevated levels in the microarray assuming that A was indeed involved in ubiquitinating AQP2. Thus, ligases whose transcripts generated a high signal in the microarray experiments were assigned larger values for P(B|A) compared with ligases whose transcripts were detected at low copy number or not detected at all in these experiments. The precise conversion scheme from signal strength to likelihoods is given in Table 1, where numerical values for the likelihoods for all six datasets are listed. See supplemental methods for the rationale for these assignments.1

Table 1.

Likelihood values for Bayes' analysis

| Dataset | Criterion | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Transcriptome, mouse mpkCCD | median normalized abundance >1 | 0.95 |

| 1 > median normalized abundance > 0.6 | 0.70 | ||

| 0.6 > median normalized abundance | 0.10 | ||

| 2 | Proteome, mouse mpkCCD | detected in proteome | 0.95 |

| not detected in proteome | 0.50 | ||

| 3 | Dot product with AQP2, mouse mpkCCD* | MAD normalized value >50 | 0.90 |

| 5 > MAD normalized value > 50 | 0.70 | ||

| 1 > MAD normalized value > 5 | 0.60 | ||

| 0 > MAD normalized value > 1 | 0.40 | ||

| MAD normalized value >1 when deviation is negative | 0.20 | ||

| 4 | RNA-sequence, rat** | RPKM values >1.0 in CNT, CCD, OMCD, and IMCD | 0.80 |

| RPKM values >1.0 in three of the four segments | 0.60 | ||

| RPKM values >1.0 in two of the four segments | 0.40 | ||

| RPKM values >1.0 in one or none of the four segments | 0.20 | ||

| 5 | UniProt subcellular location | nucleus only | 0.20 |

| cytoplasm/cytosol/membrane/endosome | 0.80 | ||

| 6 | UniProt domain/IMP | IMP | 0.80 |

| in a transmembrane protein-interacting domain | 0.80 | ||

| all others | 0.50 | ||

Criterion and probabilities used in Bayes' analysis. If there is no information on an E3 ubiquitin ligase, it received a probability P = 0.5 (coin toss). To see the rationale for these values, see Supplemental Methods.

A dot product takes vectors/arrays of numbers and returns a single value. To do this, we multiply the protein abundance levels for aquaporin-2 and the E3 ligase in each fraction and then sum the products over all of the fractions to end with a single value. We created dot products between aquaporin-2 and each of the E3 ubiquitin ligases found in the differential centrifugation fractions of cultured mouse mpkCCD cells. These dot products were used to assign probabilities to each E3 ligase based on their colocalization with aquaporin-2. To create these probabilities, we used median absolute deviation (MAD), which is defined as the median of the absolute deviations from the median (11). We found the median absolute deviation, and then divided each ligase's absolute deviation from the median by it.

Aquaporin-2 is found primarily in the renal rat connecting tubule (CNT), cortical collecting duct (CCD), outer medullary collecting duct (OMCD), and inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD). E3 ligases were given probabilities dependent on how many of these tubule segments they were found in.

The Bayesian analysis underwent sensitivity testing using Spearman's rank correlation (ρ), which gives a nonparametric measure of the statistical dependence between two variables. In our case, we looked at the correlation between the ranking of E3 ligases when all datasets are used in the Bayesian analysis versus the ranking when one dataset is excluded. The coefficient ranges from −1 to +1 with −1 indicating a perfectly negative dependence (when the first variable increases, the second decreases), 0 indicating no dependence, and 1 indicating a perfectly positive dependence (as the first variable increases, so does the second) between the two variables. We proceeded by rank ordering the E3 ligases from most probable (rank of 1) to least probable to ubiquitinate AQP2. If two or more E3 ligases tied for a rank we assigned them the average of the ranks. Then, we removed one dataset and determined the new rankings. These were compared with the original rankings using ρ, which was determined by the equation (27)

Here, n is the total number of E3 ubiquitin ligases and di2 is the difference between the old and new rankings of a particular E3 ligase squared. However, because the ranking lists included E3 ligases with tied ranks, a correction factor had to be added in for each tied rank, changing the ∑di2 term to ∑di2 + ∑cfi, where cfi is the ith correction factor needed. To find the correction factor we used the equation

where m is the number of E3 ligases tied for that rank. We did this analysis six times, each time deleting one of the six datasets used in the Bayesian analysis.

RESULTS

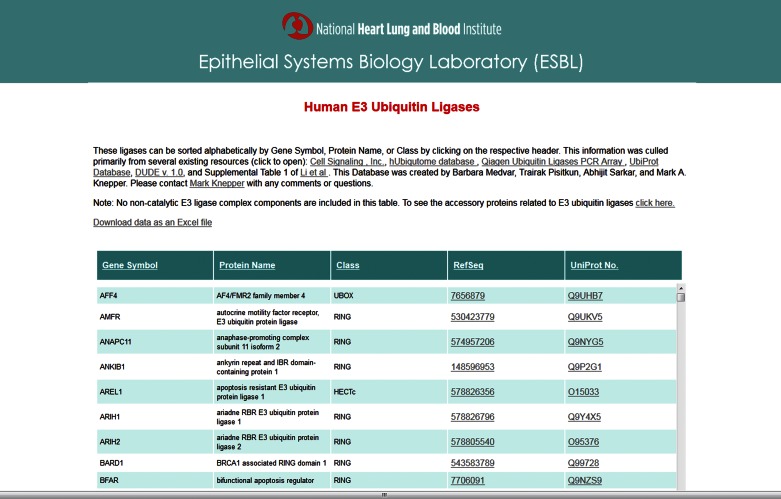

The goal was to identify ubiquitin E3 ligases that may play a role in the regulation of renal collecting duct function, especially the regulation of the AQP2 water channel. The strategy was to employ Bayes' rule with existing prior data from multiple sources to rank all ubiquitin E3 ligases with regard to probability of ubiquitinating AQP2. To do such an analysis, a list of all E3 ligases present in mammalian genomes was required. However, because of the lack of a fully curated list of known E3 ligases, we compiled our own list (methods) containing 377 human proteins. This dataset has been made available as a freely accessible database located at https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/E3-ligases/. A screenshot of the database webpage is shown in Fig. 1. The webpage is sortable on the basis of different attributes by clicking on the column headers. A link is provided to allow users to download the data into an electronic spreadsheet (lower left).

Fig. 1.

A publicly available webpage was created to provide users with a comprehensive list of E3 ligases in the human genome. Access to this webpage can be found at https://helixweb.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/E3-ligases/. All sources that have been used can be found in the first paragraph. There is a link to a separate database of accessory proteins related to E3 ubiquitin ligases, as well as a link to download the data to an Excel file. The data on this webpage can be sorted alphabetically by gene symbol, protein name, class, RefSeq number, or UniProt number.

Aside from the 377 E3 ligase proteins, there are many accessory proteins that are components of E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes. These were placed in a separate Database of Human E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Accessory Proteins (https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/E3-ligases/RelatedProteins.html). This list includes BTB, SOCS-box, F-box, Cullin, PHD, CPSF_A, UBA_4, and zf-A20 domain proteins.

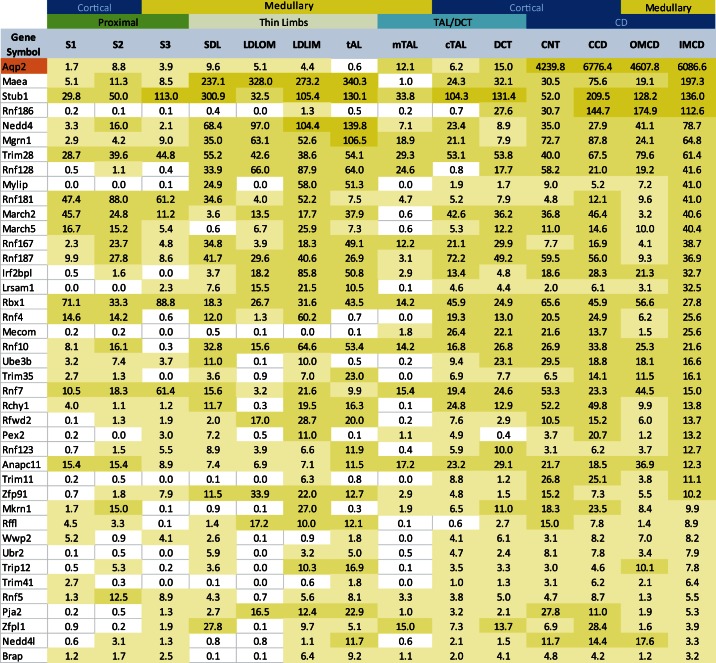

Which of the 377 E3 ligases in the mammalian genome could be responsible for ubiquitination of AQP2? Using Bayes' rule, we started with equal a priori probabilities for each of the 377 E3 ligases (Table 2, column 4) and sequentially updated all probabilities using various large-scale datasets. We first used Bayes' rule to update probabilities based on RNA-seq transcriptomic analysis of microdissected rat collecting duct segments (15) (Table 2, column 5), arguing that the E3 ligases known to be expressed in collecting duct cells are more likely to ubiquitinate AQP2 than those that are not. Table 3 lists the most abundant HECT domain, RING domain, and U-box domain E3 ligase transcripts in each collecting duct segment, as well as in each segment of the nephron included for comparison (see Supplementary Dataset S1 for full list of expressed E3 ligases). This table also includes the most abundant transporter transcripts. AQP2 is the dominant transporter transcript in the connecting tubule (CNT), cortical collecting duct (CCD), outer medullary collecting duct (OMCD), and inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD). Since AQP2 ubiquitination presumably occurs in all collecting duct segments, the E3 ligases most likely to be involved in the ubiquitination of AQP2 should be expressed in all of these segments. Figure 2 shows all E3 ubiquitin ligases with reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM) values of at least 1.0 in each of these four collecting-duct segments, compared with levels in nephron segments. These 40 E3 ubiquitin ligases are likely to include the E3 ligases that ubiquitinate AQP2.

Table 2.

Top 20 ranked E3 ubiquitin ligases based on Bayesian analysis

| Column 1 Rank | Column 2 Gene Symbol | Column 3 Class | Column 4 Initial Probability | Column 5 Rat RNA-seq | Column 6 mpkCCD Transcriptome | Column 7 mpkCCD Proteome | Column 8 Dot Product w/AQP2 | Column 9 UniProt Subcellular Location | Column 10 UniProt Domain/IMP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nedd4 | HECTc | 0.0027 | 0.0058 | 0.0104 | 0.0122 | 0.0171 | 0.0198 | 0.0271 |

| 1 | Nedd4L | HECTc | 0.0027 | 0.0058 | 0.0104 | 0.0122 | 0.0171 | 0.0198 | 0.0271 |

| 3 | Amfr | RING | 0.0027 | 0.0058 | 0.0104 | 0.0122 | 0.0146 | 0.0170 | 0.0232 |

| 4 | Stub1 | UBOX | 0.0027 | 0.0058 | 0.0104 | 0.0122 | 0.0220 | 0.0255 | 0.0217 |

| 5 | Itch | HECTc | 0.0027 | 0.0043 | 0.0078 | 0.0092 | 0.0128 | 0.0149 | 0.0203 |

| 6 | Zfpl1 | RING | 0.0027 | 0.0058 | 0.0076 | 0.0090 | 0.0126 | 0.0146 | 0.0199 |

| 7 | Trip12 | HECTc | 0.0027 | 0.0058 | 0.0104 | 0.0122 | 0.0171 | 0.0198 | 0.0169 |

| 8 | Prpf19 | UBOX | 0.0027 | 0.0043 | 0.0078 | 0.0092 | 0.0165 | 0.0191 | 0.0163 |

| 9 | Syvn1 | RING | 0.0027 | 0.0043 | 0.0057 | 0.0068 | 0.0094 | 0.0109 | 0.0150 |

| 10 | Anapc11 | RING | 0.0027 | 0.0058 | 0.0104 | 0.0122 | 0.0146 | 0.0170 | 0.0145 |

| 11 | March5 | RING | 0.0027 | 0.0058 | 0.0055 | 0.0064 | 0.0090 | 0.0104 | 0.0142 |

| 12 | Rnf130 | RING | 0.0027 | 0.0029 | 0.0038 | 0.0045 | 0.0081 | 0.0094 | 0.0128 |

| 13 | Ppil2 | UBOX | 0.0027 | 0.0043 | 0.0078 | 0.0092 | 0.0128 | 0.0149 | 0.0127 |

| 14 | Brap | RING | 0.0027 | 0.0058 | 0.0076 | 0.0090 | 0.0126 | 0.0146 | 0.0125 |

| 15 | Smurf2 | HECTc | 0.0027 | 0.0043 | 0.0078 | 0.0092 | 0.0073 | 0.0085 | 0.0116 |

| 16 | Trim25 | RING | 0.0027 | 0.0029 | 0.0052 | 0.0061 | 0.0110 | 0.0127 | 0.0109 |

| 17 | Cyhr1 | RING | 0.0027 | 0.0058 | 0.0076 | 0.0090 | 0.0108 | 0.0125 | 0.0107 |

| 18 | Rnf128 | RING | 0.0027 | 0.0058 | 0.0104 | 0.0064 | 0.0064 | 0.0074 | 0.0102 |

| 18 | Rnf167 | RING | 0.0027 | 0.0058 | 0.0104 | 0.0064 | 0.0064 | 0.0074 | 0.0102 |

| 18 | Rnf5 | RING | 0.0027 | 0.0058 | 0.0104 | 0.0064 | 0.0064 | 0.0074 | 0.0102 |

The 20 E3 ubiquitin ligases most likely to ubiquitinate aquaporin-2 (Aqp2) based on Bayesian analysis. The Bayesian analysis is sequential, with column 10 being the final ranking of E3 ligases. Columns 5–10 show the Bayesian probabilities for the E3 ligases after including the following datasets: rat RNA-seq transcriptomic data in collecting duct tubule segments (column 5) (15), mpkCCD transcriptomic data from Affymetrix expression microarray experiments (column 6) (33), mpkCCD proteomic data from LC-MS/MS quantification (column 7) (32), the dot product of each E3 ligase and Aqp2 in subcellular fractionation data (column 8) (32), the location of the E3 ligase within the cell based on UniProt Gene Ontology cellular component terms (column 9), and E3 ligases identified in UniProt as integral membrane proteins or having membrane-interacting domains (column 10).

Table 3.

Most abundant E3 ubiquitin ligase and transporter transcripts in every tubule segment

| RING | HECT | U-BOX | Transporters | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Rbx1 | Wwp2 | Nosip | Slc34a1 |

| S2 | Rnf181 | Wwp1 | Stub1 | Slc34a1 |

| S3 | Rbx1 | Wwp2 | Stub1 | Slc7a13 |

| SDL | Maea | Nedd4 | Stub1 | Aqp1 |

| LDLOM | Maea | Nedd4 | Stub1 | Aqp1 |

| LDLIM | Maea | Nedd4 | Stub1 | Aqp1 |

| tAL | Maea | Nedd4 | Stub1 | Cldn4 |

| mTAL | Trim28 | Nedd4 | Stub1 | Slc12a1 |

| cTAL | Rnf187 | Nedd4 | Stub1 | Clcnkb |

| DCT | Trim28 | Ube3b | Stub1 | Slc12a3 |

| CNT | Mgrn1 | Nedd4 | Stub1 | Aqp2 |

| CCD | Rnf186 | Nedd4 | Stub1 | Aqp2 |

| OMCD | Rnf186 | Nedd4 | Stub1 | Aqp2 |

| IMCD | Maea | Nedd4 | Stub1 | Aqp2 |

E3 ubiquitin ligase transcript with the highest reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM) values for every tubule segment. Also listed is the most highly expressed transporter transcript for each segment.

Fig. 2.

E3 ubiquitin ligase transcripts most highly expressed in collecting duct segments and their distribution along renal tubule. Aquaporin-2 (AQP2) is expressed in the connecting tubule (CNT), the cortical collecting duct (CCD), outer medullary collecting duct (OMCD), and the inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD). Only E3 ubiquitin ligases that have a transcript level of 1.0 reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM) in all 4 of these segments are shown. RPKM values are from Lee et al. (15).

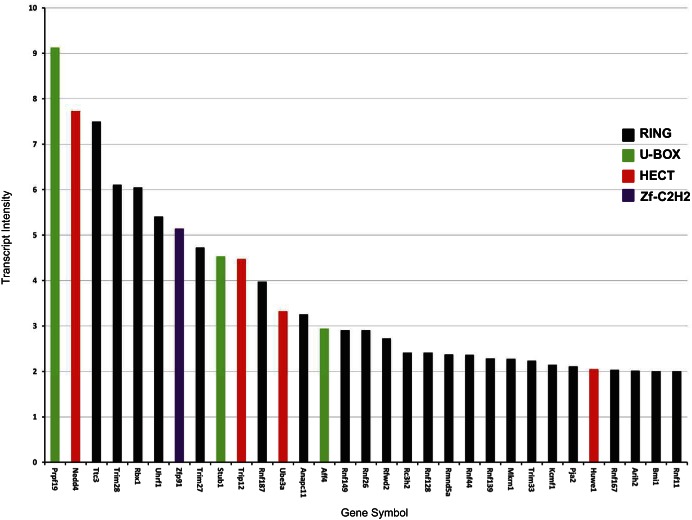

Next, we incorporated transcriptomic data from Affymetrix expression microarray experiments in cultured mouse mpkCCD cells (33), arguing that the likelihood of an E3 ligase ubiquitinating AQP2 (or any other protein) is greatest if its transcript was known to be expressed in collecting duct cells (Table 2, column 6). A total of 166 E3 ubiquitin ligase transcripts were identified in the dataset, placing these at a higher probability than the remaining 211. Figure 3 shows the 31 most abundant E3 ubiquitin ligase transcripts found in the mpkCCD transcriptome. Of the top 31 E3 ubiquitin ligase transcripts, three code for U-box domain proteins (Prpf19, Stub1, and Aff4), four code for HECT domain proteins (Nedd4, Trip12, Ube3a, and Huwe1), and one codes for a zf-C2H2 domain protein (Zfp91). The other 23 transcripts code for RING domain proteins.

Fig. 3.

The 31 most abundant E3 ubiquitin ligase transcripts in mouse mpkCCD cells. The bars are color-coded to indicate the class of each E3 ligase based on the presence of a U-box, RING, HECT, or zf-C2H2 domain. The transcript values are from the mouse mpkCCD transcriptome identified using Affymetrix expression microarrays (31).

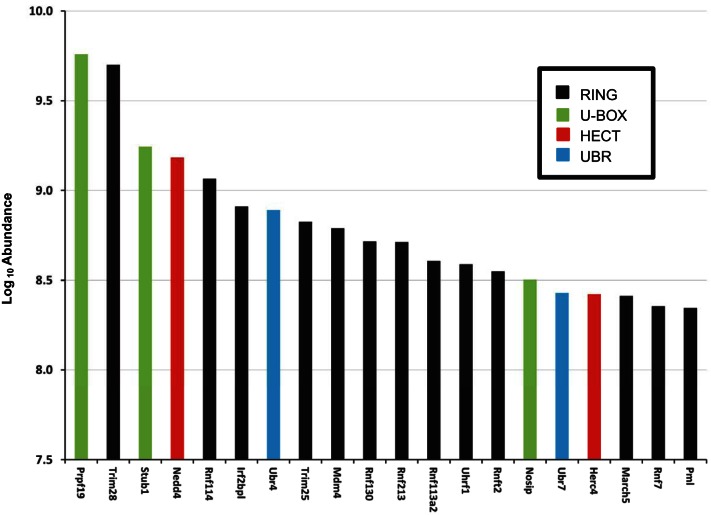

The third dataset we used was proteomic data from liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) quantification of proteins expressed in mpkCCD cells (32) (Table 2, column 7). We argued that E3 ligases detectable by protein mass spectrometry were more likely to ubiquitinate AQP2 than those that were not detectable. E3 ligases with measurable abundance levels in mpkCCD cells amounted to 115 proteins. Figure 4 shows the 20 E3 ligases with the highest protein abundance levels. Three of these are U-box domain proteins (Prpf19, Stub1, and Nosip), two are HECT domain proteins (Nedd4 and Herc4), and two are UBR domain proteins (Ubr4 and Ubr7). The other 13 proteins are RING domain proteins. Among the 115 E3 ubiquitin ligases found in the proteomic data and the 166 E3 ubiquitin ligases found in the transcriptomic data in mpkCCD cells, 79 overlap. The transcriptomic data and proteomic lists for mpkCCD cells are available in Supplementary Dataset S2.

Fig. 4.

The 20 most abundant E3 ubiquitin ligase proteins in mouse mpkCCD cells. The ligases are color coded to indicate the class of each E3 ligase based on the presence of a U-box, RING, HECT, or UBR domain. The abundance levels for each E3 ligase was found using the relative protein abundances in mouse mpkCCD cells (30).

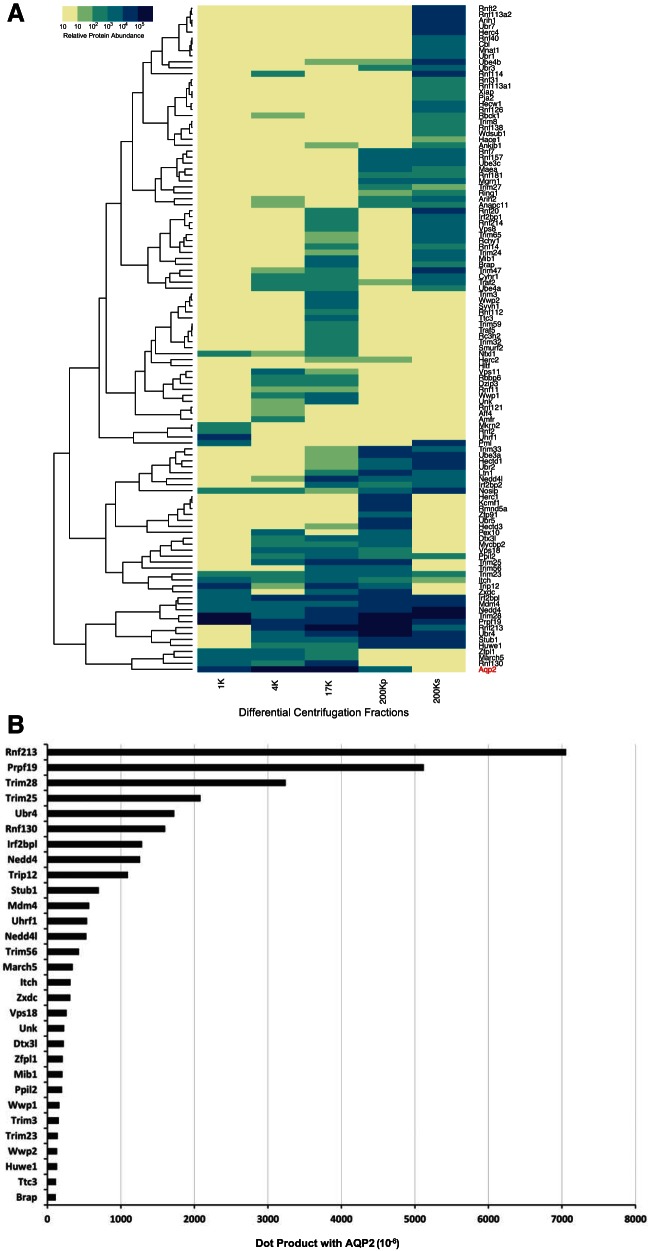

We then incorporated subcellular fractionation data quantifying the extent of colocalization of AQP2 and each E3 ubiquitin ligase based on proteomic data from differential centrifugation of cultured mpkCCD cells (32) (Table 2, column 8). The argument here is that for ubiquitination to occur, AQP2 and the respective E3 ligase must be in the same subcellular fraction. Figure 5A shows a heat-map of protein abundances in differential centrifugation fractions of cultured mouse mpkCCD cells comparing the distributions of AQP2 (red) and 138 E3 ligases. Results from hierarchical clustering are shown on the left. E3 ubiquitin ligases that cluster most closely with AQP2 are Rnf130, March5, Zfpl1, Huwe1, Stub1, Ubr4, Rnf213, Prpf19, Trim28, Nedd4, Mdm4, and Irf2bpl. To quantify the overlap we formed a dot product of the abundance value vectors for AQP2 and each E3 ubiquitin ligase across all five fractions (see methods). Figure 5B shows the E3 ligases with the top 30 dot products. The top 12 E3 ligases by this measure are Rnf213, Prpf19, Trim28, Trim25, Ubr4, Rnf130, Irf2bpl, Nedd4, Trip12, Stub1, Mdm4, and Uhrf1. We incorporated the dot product values into the Bayesian analysis, giving a further refinement of the E3 ubiquitin ligase ranking (Table 2, column 8).

Fig. 5.

Comparisons of the abundance of AQP2 and E3 ubiquitin ligases in subcellular fractions from mouse mpkCCD cells. A: coclustering of AQP2 and all E3 ubiquitin ligases that were found in the indicated differential centrifugation fractions from mpkCCD cells. AQP2 is the bottom-most protein on the heat-map. B: dot products between the distribution vector for AQP2 and the distribution vector for each E3 ligase found in the mpkCCD subcellular fractions. Only the top 30 are shown.

Next, we sought to incorporate general information about each of the E3 ligases available from public databases. AQP2 is a transmembrane protein processed in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus and delivered to the plasma membrane via the endosomal pathway (31). Thus, E3 ubiquitin ligases that are expressed mainly in the cell nucleus are less likely to ubiquitinate AQP2 than those present in the cytoplasm. Gene Ontology cellular component terms were extracted for all E3 ligases and were used to estimate probability of cytoplasmic expression (vs. nuclear expression), and served as inputs in the Bayesian analysis (Table 2, column 9). Those reported to be present in both cytoplasm and nucleus were assigned the same probabilities as those present in cytoplasm alone. The data are found in Supplemental Table S1.

Finally, we made the assumption that E3 ligases that are also integral membrane proteins or have membrane-interacting domains are more likely to interact with AQP2, an integral membrane protein, than those that are not. These E3 ligases were identified as described in methods. Combining these into the Bayesian analysis (Table 2, column 10), we obtained a final ranked list of E3 ubiquitin ligases (Table 2, column 10) most likely to ubiquitinate AQP2 headed by Nedd4 and Nedd4l (tied for most probable), Amfr, Stub1, Itch, and Zfpl1. Three of these top six proteins are HECT domain proteins (Nedd4, Nedd4l, and Itch), two of these proteins are RING domain proteins (Amfr and Zfpl1), and Stub1 is a U-box domain protein.

The Bayesian analysis underwent sensitivity tests using Spearman's correlation coefficient (ρ), as described in methods. Six ρ values were calculated by removing a different dataset each time and running a regression analysis versus the full dataset. Their values ranged from 0.804 to 0.972, implying that no specific dataset had undue weight in creating the rankings. Furthermore, this analysis showed the input probability values assumed for a particular dataset did not have a critical impact on the overall analysis.

AQP2 is a transmembrane protein, which is initially assembled in the ER. When proteins in the ER are misfolded, they are degraded by the ERAD (endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation) pathway (17). It is known that E3 ubiquitin ligases are involved in this pathway (17), including many that are expressed in collecting duct cells. These hypothetically could ubiquitinate misfolded AQP2. However, our focus in this paper is on the degradation of normally folded and apically trafficked AQP2. Among the highly ranked ubiquitin ligases in Table 2, five (Amfr, Stub1, Syvn1, Trim25, and Rnf5) are known to be associated with the ERAD pathway based on their Gene Ontology terms.

DISCUSSION

This paper reports a comprehensive curated set of E3 ubiquitin ligases expressed in the human genome, freely accessible as an online webpage, which provides a resource that can be used by other investigators. Second, it reports a ranking of E3 ligases with regard to the probability that they ubiquitinate AQP2 in the mammalian collecting duct. We consider these two objectives in turn.

We compiled a nearly comprehensive listing of E3 ubiquitin ligases in the human genome. For this we decided to divide E3 ligase-related proteins into two groups, viz. the ligases themselves and accessory proteins that form complexes with the ligases and are necessary for ligase function or targeting. These lists are provided to potential users in two separate online databases (see results for URLs). Most of the E3 ligases are in one of three groups, viz. HECT domain, UBOX domain, and RING domain E3 ligases. In creating these databases, we were motivated by the recent growth of systems biology, which emphasizes investigation of all proteins of a given class in parallel using large-scale approaches such as protein mass spectrometry and next-generation DNA sequencing (14). Comprehensive gene or protein lists such as those provided here are needed to extract information about specific classes of proteins from such large-scale data sets. Although this list was curated from the human genome, we expect the list to be almost identical in mouse or rat in which most physiological studies are carried out.

The second task was to answer the question “What E3 ubiquitin ligases are most likely to ubiquitinate aquaporin-2?”. Using our master list of E3 ligases in combination with Bayes' rule for data integration, we ranked the ligases from most probable to least probable to ubiquitinate AQP2. Bayes' rule quantifies the intuitive process that most scientists use in merging prior data with new experimental findings, sequentially taking different types of information into account in an overall inference. We started by assigning uniform prior probabilities to the 377 E3 ligases and then used six independent experimental datasets to generate updated posterior probabilities. This approach produced two top-ranked E3 ligases, Nedd4 and Nedd4l, that have already been widely studied in the area of regulation of collecting duct transport. In fact, of the top 20 E3 ubiquitin ligases we found, only Nedd4 and Nedd4l have been studied in the collecting duct (based on querying PubMed using the E3 ligase gene symbols and the word “collecting” as search terms). Importantly, even though we did not use data from the reductionist literature in our analysis, the Bayes' ranking was compatible with what might have been guessed from the prior body of reductionist knowledge. This concordance of conclusions provides an a posteriori validation of the Bayes' rule based analysis. Previously, we have used Bayes' rule in a similar fashion to identify the protein kinases most likely to phosphorylate AQP2 (2).

It may be informative to examine the data for Nedd4 and Nedd4l to understand the basis for their top ranking among all E3 ligases. First, in single-tubule transcriptomic studies in rats (15), both Nedd4 and Nedd4l mRNAs were found to be expressed in all four collecting duct segments (CNT, CCD, OMCD, and IMCD) (https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/NephronRNAseq/All_transcripts.html). Second, in cultured mouse mpkCCD cells, Nedd4 ranked 2nd in mRNA abundance (33) and 4th in protein abundance (32) among the 377 E3 ligases in the mouse genome. Also in mpkCCD cells, Nedd4l ranked 34th in mRNA abundance and 27th in protein abundance. Third, with regard to subcellular colocalization with AQP2 in mpkCCD cells, Nedd4 ranked 10th and Nedd4l ranked 15th among the 377 E3 ligases according to their dot products versus AQP2 across differential centrifugation fractions (32). Next, Uniprot subcellular localization annotations were “Golgi apparatus, apicolateral plasma membrane, cell cortex, chromatin, cytoplasm, cytosol, extracellular exosome, membrane raft, microvillus, perinuclear region of cytoplasm, plasma membrane, and ubiquitin ligase complex” for Nedd4 and “cytosol, extracellular exosome, intracellular, nucleoplasm, and plasma membrane” for Nedd4l. Finally, both Nedd4 and Nedd4l have C2 domains, which are involved in calcium-dependent targeting of proteins to cellular membranes. Prior studies have shown that the water-permeability response to vasopressin in isolated perfused collecting ducts is dependent on calcium mobilization by vasopressin (4, 29). Also they have WW domains that allow them to interact with certain membrane proteins with proline-rich PY motifs and their regulatory complexes. Beyond this, large-scale proteomics studies have provided additional supporting evidence that were not included in the data integration described in this paper. Specifically, short-term exposure of rat IMCD cells to dDAVP (1 nM) increased phosphorylation of Nedd4l protein at Threonine-439 protein (10). This site, identified by Snyder et al. (28) as a target for both Sgk1 and protein kinase A, causes Nedd4l to detach from cell membranes when phosphorylated. Another large-scale proteomic study (26) showed that vasopressin causes redistribution of Nedd4 protein from nucleus to cytoplasm in mpkCCD cells.

Previous studies have demonstrated an important role for Nedd4l protein in the regulation of another collecting duct transporter, epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) (28). This study raises the possibility that Nedd4l may also be involved in regulation of AQP2, in particular in the renal IMCD, in which active transport of Na is extremely low to nonexistent (25) and which has relatively low levels of the three ENaC subunits (15). One qualifying fact, however, is the lack of a bona fide PY motif in AQP2, which is the binding site for the WW domains in Nedd4l (8). It is possible that Nedd4l binds to AQP2 indirectly through some intermediary protein. Alternatively, it is possible that the WW domains of Nedd4l or Nedd4 are not involved in targeting to AQP2 and membrane targeting is instead achieved through the C2 domains in Nedd4.

Another group previously used (non-Bayesian) systems biology techniques to address the question of what E3 ligases might ubiquitinate AQP2 (16). They combined transcriptome analysis and LC-MS/MS in whole rat inner medullas to identify a limited number of E3 ligases and accessory proteins in both datasets. Interestingly, among the abundant E3 ligases identified was Nedd4, providing further support for a role for this ligase. The authors also provided functional evidence for Nedd4 in the regulation of AQP2 half-life via siRNA knockdowns in mpkCCD cells.

It could be argued that the likelihood estimates for individual datasets used in the Bayesian analysis are somewhat arbitrary. However, these probabilities numerically encode expert judgement on the quality of the experimental data and complicating factors in the original experimental design. Their value is in making such judgements explicit and thus subject to review by others. Furthermore, the assignments are constrained by common rules of logic. For example, it is reasonable that an E3 ubiquitin ligase found in the collecting duct proteome is more probable to ubiquitinate AQP2 in mammals than an E3 ligase that is not found in the proteome. Moreover, the assignment of 0.5 probability when no information is available also provides an important constraint to the analysis. When we possess additional information that a particular ligase might be involved in ubiquitination, we would naturally assign a probability >0.5 for that ligase. Conversely, if information exists suggesting that a particular ligase is not involved in ubiquitination, we would assign it a probability <0.5. An important check on these probabilities is to systematically assess the impact on the final results of varying one or more of these assignments. We performed such a sensitivity analyses and found that our results were quite robust to changes in the input probabilities.

It could be argued that information about the structure of the various ubiquitin ligases and the amino acid sequences surrounding the target lysine (K270 of AQP2) could be used to refine the Bayesian analysis beyond what was done in this paper, similar to what is often done in predicting what kinase(s) phosphorylate particular sites (2). However, our review of the literature did not reveal a systematic classification of E3 ligase specificities, and additional studies would be needed to obtain such information across the ubiquitome. It appears likely that the specificity of most E3 ligases is determined by the accessory protein(s) that they complex with.

There are several candidates for roles in AQP2 ubiquitination beyond Nedd4l and Nedd4. The other top 18 E3 ligases will need to be studied by reductionist and or systems biology-based approaches to ascertain their roles. To lay out possible physiological roles for these ligases, we have extracted information on the molecular functions of each from their individual UniProt protein records (Table 4).

Table 4.

Top 20 E3 ubiquitin ligases and their molecular functions

| Bayesian Ranking | Gene Symbol | Class | Annotation | Functional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nedd4 | HECTc | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase NEDD4 isoform 1 | Specifically ubiquitinates ‘Lys-63’ in target proteins. Involved in pathway leading to degradation of VEGFR-2/KDFR, independently of its ubiquitin-ligase activity. Monoubiquitinates IGF1R at multiple sites. Ubiquitinates FGFR1, TNK2, and BRAT1. Promotes ubiquitination of RAPGEF2. |

| 1 | Nedd4L | HECTc | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase NEDD4-like isoform 6 | Promotes ubiquitination and internalization of various plasma membrane channels such as ENaC, Nav1.2, Nav1.3, Nav1.5, Nav1.7, Nav1.8, Kv1.3, EAAT1, or CLC5. Ubiquitinates BRAT1. Plays a role in dendrite formation by melanocytes. |

| 3 | Amfr | RING | autocrine motility factor receptor | Polyubiquitinates number of proteins. Is a component of VCP/p97-Amfr/gp78 complex. Involved in last step of ERAD |

| 4 | Stub1 | UBOX | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase CHIP isoform b | Catalyzes polyubiquitination by amplyfying the HUWE1/Arf-bp1-dependent monoubiquitination. Modulates the activity of several chaperone complexes, including Hsp70, Hsc70, and Hsp90. |

| 5 | Itch | HECTc | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Itchy homolog isoform 3 | Involved in the control of inflammatory signaling pathways |

| 6 | Zfpl1 | RING | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase ZFP91 isoform 2 | ER to Golgi transport. Involved in maitenance of the integrity of the cis-Golgi, possibly via its interation with Golga2/GM130. Transmembrane protein. |

| 7 | Trip12 | HECTc | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase TRIP12 isoform a | Involved in ubiquitin fusion degradation (UDF). Key regulator of DNA damage response. Mediates ubiquitination of isoform p19ARF/ARF of CDKN2A in normal cells. |

| 8 | Prpf19 | UBOX | premRNA-processing factor 19 | Core component of PRP19C/Prp19 complex/NTC/Nineteen complex. Mediates polyubiquitination of U4 spliceosomal protein Prpf3. May couple the transcriptional and spliceosomal machineries. |

| 9 | Syvn1 | RING | synovial apoptosis inhibitor 1, synoviolin | Accepts ubiquitin specifically from ER-associated UBC7. Component of ERAD. Protects cells from ER stress-induced apoptosis. |

| 10 | Anapc11 | RING | anaphase-promoting complex subunit 11 isoform 2 | Catalytic component of anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome. Moderate levels in kidney. |

| 11 | March5 | RING | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase MARCH5 | Mitochondrial E3 ligase. Plays a crucial role in control of mitochondrial morphology. Acts as positive regulator of mitochondrial fission. May play role in prevention of cell senescence. Transmembrane protein. |

| 12 | Rnf130 | RING | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase RNF130 isoform 2 precursor | Transmembrane protein. |

| 13 | Ppil2 | RING | peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase-like 2 isoform b | By ′Lys-48′-linked polyubiquitination of proteins, could target them for proteasomal degradation. May catalyze the cis-trans isomerization of proline imidic peptide bonds in oligopeptides thereby assisting the folding of proteins. |

| 14 | Brap | RING | BRCA1 associated protein | A RAS responsive E3 ligase. Negatively regulates MAP kinase activation. May act as a cytoplasmic retention protein with role in nuclear transport. |

| 15 | Smurf2 | RING | SMAD specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 | Interacts with SMAD1 and SMAD7 to trigger their ubiquitination and proteasome-dependent degradation. Coexpression with SMAD1 results in considerable decrease in steady-state level of SMAD1 protein. |

| 16 | Trim25 | RING | E3 ubiquitin/ISG15 ligase TRIM25 | Also an ISG15 ligase. Involved in immune defense by ubiquitinating DDX58. Mediates estrogen action in various target organs. Mediates ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of ZFHX3. |

| 17 | Cyhr1 | RING | cysteine and histidine-rich protein 1 isoform 2 precursor | No information on function. |

| 18 | Rnf128 | RING | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase RNF128 isoform 1 precursor | Inhibitor of cytokine gene transcription. Sensitizes ectoderm to respond to neural-inducing signals. Ubiquitinates ARPC5 and COR1A. Transmembrane protein. |

| 18 | Rnf167 | RING | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase RNF167 precursor | Transmembrane protein. |

| 18 | Rnf5 | RING | ring finger protein 5, E3 ubiquitin protein ligase | May function with E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes UBE2D1/UBCH5A and UBE2D2/UBC4. Mediates ubiquitination of PXN/paxillin and sopA. May be involved in regulation of cell motility and localization of PXN/paxillin. Mediates polyubiquitination of JKAMP. Mediates polyubiquitination of TMEM173. |

Functional notes on the top 20 E3 ubiquitin ligases found with Bayesian analysis. The functional notes were found in the FUNCTION fields of UniProt records.

Summary

In this paper, we have taken a systems biology approach to addressing the question of which E3 ubiquitin ligases are involved in the regulation of AQP2. We started by compiling a comprehensive list of E3 ligases in the mammalian genome. Using this list, we used a Bayesian approach to probabilistically rank the ubiquitin ligases based on six independent, large-scale, systems-level datasets. Our data integration approach led to the identification of Nedd4 and Nedd4l as the highest ranked candidate ligases. Interestingly, this result is consistent with the reductionist literature, which was not used in our analysis. This suggests that some of the other highly ranked E3 ligases potentially involved in ubiquitination of AQP2 may be worthwhile candidates for in-depth reductionist studies.

GRANTS

The study was carried out in the Division of Intramural Research of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Projects HL-001285 and HL-006129, M. A. Knepper). T. Pisitkun is supported by the Chulalongkorn Academic Advancement into Its 2nd Century (CUAASC) Project.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.M., V.R., A.S., and M.A.K. conception and design of research; B.M. and M.A.K. performed experiments; B.M., V.R., T.P., and M.A.K. analyzed data; B.M., V.R., and M.A.K. interpreted results of experiments; B.M. and M.A.K. prepared figures; B.M. and M.A.K. drafted manuscript; B.M., V.R., A.S., and M.A.K. edited and revised manuscript; B.M., V.R., T.P., A.S., and M.A.K. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Drs. Pablo C. Sandoval, Chin-Rang Yang, Hyun Jun Jung, and Chung-Lin Chou for advice. This study utilized the high-performance computational capabilities of the Helix Systems at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (http://helix.nih.gov).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ardley HC, Robinson PA. E3 ubiquitin ligases. Essays Biochem 41: 15–30, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford D, Raghuram V, Wilson JL, Chou CL, Hoffert JD, Knepper MA, Pisitkun T. Use of LC-MS/MS and Bayes' theorem to identify protein kinases that phosphorylate aquaporin-2 at Ser256. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 307: C123–C139, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chernorudskiy AL, Garcia A, Eremin EV, Shorina AS, Kondratieva EV, Gainullin MR. UbiProt: a database of ubiquitylated proteins. BMC Bioinformatics 8: 126, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou CL, Yip KP, Michea L, Kador K, Ferraris JD, Wade JB, Knepper MA. Regulation of aquaporin-2 trafficking by vasopressin in the renal collecting duct. Roles of ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ stores and calmodulin. J Biol Chem 275: 36839–36846, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Congdon P. Bayesian Statistical Modelling. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du Y, Xu N, Lu M, Li T. hUbiquitome: a database of experimentally verified ubiquitination cascades in humans. Database (Oxford) 2011: bar055, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ecelbarger CA, Nielsen S, Olson BR, Murase T, Baker EA, Knepper MA, Verbalis JG. Role of renal aquaporins in escape from vasopressin-induced antidiuresis in rat. J Clin Invest 99: 1852–1863, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flores SY, Debonneville C, Staub O. The role of Nedd4/Nedd4-like dependant ubiquitylation in epithelial transport processes. Pflügers Arch 446: 334–338, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayashi M, Sasaki S, Tsuganezawa H, Monkawa T, Kitajima W, Konishi K, Fushimi K, Marumo F, Saruta T. Role of vasopressin V2 receptor in acute regulation of aquaporin-2. Kidney Blood Press Res 19: 32–37, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffert JD, Pisitkun T, Saeed F, Song JH, Chou CL, Knepper MA. Dynamics of the G protein-coupled vasopressin V2 receptor signaling network revealed by quantitative phosphoproteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 11: M111 014613, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huber PJ, Ronchetti EM. Robust Statistics (2nd Ed). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutchins AP, Liu S, Diez D, Miranda-Saavedra D. The repertoires of ubiquitinating and deubiquitinating enzymes in eukaryotic genomes. Mol Biol Evol 30: 1172–1187, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamsteeg EJ, Hendriks G, Boone M, Konings IB, Oorschot V, van der Sluijs P, Klumperman J, Deen PM. Short-chain ubiquitination mediates the regulated endocytosis of the aquaporin-2 water channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 18344–18349, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knepper MA. Systems biology in physiology: the vasopressin signaling network in kidney. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 303: C1115–C1124, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JW, Chou CL, Knepper MA. Deep sequencing in microdissected renal tubules identifies nephron segment-specific transcriptomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2669–2677, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee YJ, Lee JE, Choi HJ, Lim JS, Jung HJ, Baek MC, Frokiaer J, Nielsen S, Kwon TH. E3 ubiquitin-protein ligases in rat kidney collecting duct: response to vasopressin stimulation and withdrawal. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F883–F896, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemus L, Goder V. Regulation of endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation (ERAD) by ubiquitin. Cells 3: 824–847, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li W, Bengtson MH, Ulbrich A, Matsuda A, Reddy VA, Orth A, Chanda SK, Batalov S, Joazeiro CA. Genome-wide and functional annotation of human E3 ubiquitin ligases identifies MULAN, a mitochondrial E3 that regulates the organelle's dynamics and signaling. PLoS One 3: e1487, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Metzger MB, Hristova VA, Weissman AM. HECT and RING finger families of E3 ubiquitin ligases at a glance. J Cell Sci 125: 531–537, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nedvetsky PI, Tabor V, Tamma G, Beulshausen S, Skroblin P, Kirschner A, Mutig K, Boltzen M, Petrucci O, Vossenkamper A, Wiesner B, Bachmann S, Rosenthal W, Klussmann E. Reciprocal regulation of aquaporin-2 abundance and degradation by protein kinase A and p38-MAP kinase. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1645–1656, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nielsen S, Chou CL, Marples D, Christensen EI, Kishore BK, Knepper MA. Vasopressin increases water permeability of kidney collecting duct by inducing translocation of aquaporin-CD water channels to plasma membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 1013–1017, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen S, DiGiovanni SR, Christensen EI, Knepper MA, Harris HW. Cellular and subcellular immunolocalization of vasopressin-regulated water channel in rat kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 11663–11667, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen S, Frokiaer J, Marples D, Kwon TH, Agre P, Knepper MA. Aquaporins in the kidney: from molecules to medicine. Physiol Rev 82: 205–244, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandoval PC, Slentz DH, Pisitkun T, Saeed F, Hoffert JD, Knepper MA. Proteome-wide measurement of protein half-lives and translation rates in vasopressin-sensitive collecting duct cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1793–1805, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sands JM, Nonoguchi H, Knepper MA. Hormone effects on NaCl permeability of rat inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 255: F421–F428, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schenk LK, Bolger SJ, Luginbuhl K, Gonzales PA, Rinschen MM, Yu MJ, Hoffert JD, Pisitkun T, Knepper MA. Quantitative proteomics identifies vasopressin-responsive nuclear proteins in collecting duct cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1008–1018, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Correlation. In: Statistical Methods. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snyder PM, Olson DR, Kabra R, Zhou R, Steines JC. cAMP and serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase (SGK) regulate the epithelial Na+ channel through convergent phosphorylation of Nedd4-2. J Biol Chem 279: 45753–45758, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Star RA, Nonoguchi H, Balaban R, Knepper MA. Calcium and cyclic adenosine monophosphate as second messengers for vasopressin in the rat inner medullary collecting duct. J Clin Invest 81: 1879–1888, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tchapyjnikov D, Li Y, Pisitkun T, Hoffert JD, Yu MJ, Knepper MA. Proteomic profiling of nuclei from native renal inner medullary collecting duct cells using LC-MS/MS. Physiol Genomics 40: 167–183, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valenti G, Procino G, Tamma G, Carmosino M, Svelto M. Minireview: aquaporin 2 trafficking. Endocrinology 146: 5063–5070, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang CR, Tongyoo P, Emamian M, Sandoval PC, Raghuram V, Knepper MA. Deep proteomic profiling of vasopressin-sensitive collecting duct cells. I. Virtual Western blots and molecular weight distributions. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 309: C785–C798, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu MJ, Miller RL, Uawithya P, Rinschen MM, Khositseth S, Braucht DW, Chou CL, Pisitkun T, Nelson RD, Knepper MA. Systems-level analysis of cell-specific AQP2 gene expression in renal collecting duct. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 2441–2446, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.