We demonstrate in a large animal model that altering the distribution of pulmonary artery (PA) perfusion by selective lobar PA banding impairs postpneumonectomy growth of gas exchange tissue while enhancing alveolar double-capillary formation in the remaining lobes. Divergent responses between tissue and capillaries indicate that perfusion-related signals play a major role in reinitiation of compensatory lung growth, acting independently from the major signals for extravascular tissue growth, i.e., mechanical stress and strain of the parenchyma.

Keywords: lung resection, pulmonary blood flow, pulmonary artery banding, lung structure and function, alveolar angiogenesis

Abstract

Following pneumonectomy (PNX), two separate mechanical forces act on the remaining lung: parenchymal stress caused by lung expansion, and microvascular distension and shear caused by increased perfusion. We previously showed that parenchymal stress and strain explain approximately one-half of overall compensation; the remainder was presumptively attributed to perfusion-related factors. In this study, we directly tested the hypothesis that perturbation of regional pulmonary perfusion modulates post-PNX lung growth. Adult canines underwent banding of the pulmonary artery (PAB) to the left caudal (LCa) lobe, which caused a reduction in basal perfusion to LCa lobe without preventing the subsequent increase in its perfusion following right PNX while simultaneously exaggerating the post-PNX increase in perfusion to the unbanded lobes, thereby creating differential perfusion changes between banded and unbanded lobes. Control animals underwent sham pulmonary artery banding followed by right PNX. Pulmonary function, regional pulmonary perfusion, and high-resolution computed tomography of the chest were analyzed pre-PNX and 3-mo post-PNX. Terminally, the remaining lobes were fixed for detailed morphometric analysis. Results were compared with corresponding lobes in two control (Sham banding and normal unoperated) groups. PAB impaired the indices of post-PNX extravascular alveolar tissue growth by up to 50% in all remaining lobes. PAB enhanced the expected post-PNX increase in alveolar capillary formation, measured by the prevalence of double-capillary profiles, in both unbanded and banded lobes. We conclude that perfusion distribution provides major stimuli for post-PNX compensatory lung growth independent of the stimuli provided by lung expansion and parenchymal stress and strain.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

We demonstrate in a large animal model that altering the distribution of pulmonary artery (PA) perfusion by selective lobar PA banding impairs postpneumonectomy growth of gas exchange tissue while enhancing alveolar double-capillary formation in the remaining lobes. Divergent responses between tissue and capillaries indicate that perfusion-related signals play a major role in reinitiation of compensatory lung growth, acting independently from the major signals for extravascular tissue growth, i.e., mechanical stress and strain of the parenchyma.

compensatory lung growth is a robust phenomenon that has been demonstrated in multiple mammalian species (10, 27, 28, 30, 31, 37). In adult canines following surgical removal of ∼58% of total lung units by right pneumonectomy (PNX), ventilation and perfusion to the remaining lung increase by a factor of ∼1/(1-0.58) = 2.38. Mechanical forces imposed on the remaining parenchyma and microvasculature reinitiate lung growth in an age- and threshold-dependent manner, leading to significant functional compensation. In young canines, post-PNX stimuli augment developmental stimuli resulting in vigorous accelerated lung growth that nearly normalizes alveolar structural dimensions and lung diffusing capacity upon reaching adulthood (40, 42), although significant abnormalities in pulmonary hemodynamics and work of breathing persist (41). In adult canines, post-PNX lung growth requires a higher stimulus threshold (loss of ∼50% of lung units) and partially restores long-term alveolar structural dimensions and lung diffusing capacity (16, 22, 37). Thus the potential for alveolar-capillary regrowth is retained in adult lungs although the incomplete compensation suggests a need for augmentation.

Compensatory lung growth does not simply reactivate developmental events, but also invokes additional mechanisms not available to or fully utilized in the developing lung (52). Hundreds of interacting genes are activated (29) that in turn signal thousands of target molecules in diverse cell types involving nearly all of the major homeostatic pathways to effect spatially and temporally coordinated responses, culminating in the balanced addition of alveolar septal tissue and capillaries. An initial cellular proliferative phase is followed by progressive scaffold remodeling at microlevels and macrolevels (50) to optimize mechanics, minimize resistance to diffusion, and efficiently match disparate heterogeneous gas exchange steps including ventilation, perfusion, diffusion, and chemical reaction with hemoglobin. Physical stress and strain (deformation) are thought to impose fundamental signals for initiating post-PNX compensatory growth (9, 17, 19, 33, 36, 46, 51). Two types of mechanical forces are invoked post-PNX: 1) parenchyma deformation due to expansion of the remaining lobes and 2) alveolar microvascular distension and shear due to redirection of the entire cardiac output through one lung. In earlier studies, our group used an inflatable silicone prosthesis to reversibly prevent post-PNX expansion of the remaining lung and showed that the increase in parenchymal stress-strain explains approximately one-half of overall compensatory response (9, 17, 19, 36, 46); the remainder was presumably due to increased perfusion and/or metabolic factors. However, the contribution of perfusion-related signals to compensatory lung growth has not been directly examined.

In this study, we directly tested the hypothesis that perfusion perturbation modulates post-PNX lung growth. Using a well-established adult canine model, we altered the distribution of post-PNX pulmonary perfusion to the remaining lobes by banding one lobar pulmonary artery (PA) to its ex vivo relaxed circumference, which did not prevent subsequent post-PNX increase in perfusion to the banded lobe but accentuated the increase in perfusion to the unbanded remaining lobes. Using each animal as its own pre- to post-PNX control, we measured the post-PNX changes in lobar PA blood flow, physiological function, in vivo anatomy by high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), and postmortem alveolar septal structure between PA-banded (PAB) and sham PA-banded animals.

METHODS

Animals.

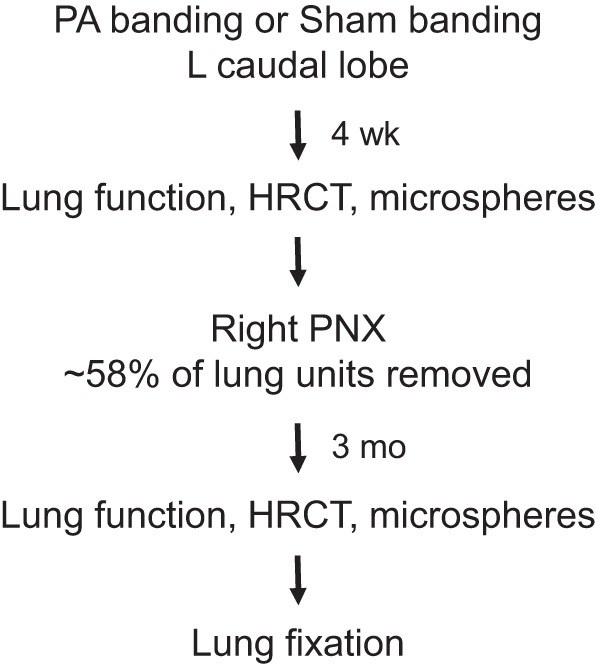

The Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center approved all of the procedures. Adult litter-matched male mixed-breed hounds (∼12 mo old at the time of surgery, 20.3 ± 2.6 kg, mean ± SD) were obtained from approved vendors. The flow of experimental procedures is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the experiments. HRCT, high-resolution CT; PNX, pneumonectomy.

Lobar PA banding.

The animal was fasted overnight and premedicated with acepromazine (0.2 mg/kg im), glycopyrrolate (0.01 mg/kg sc), buprenorphine (0.02 mg/kg sc), cefazolin (22 mg/kg iv), and furosemide (2 mg/kg iv). Anesthesia was induced with propofol (4 mg/kg iv) and maintained with isoflurane. Following tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation (tidal volume 6-9 ml/kg), a left lateral thoracotomy was performed through the sixth intercostal space. A piece of Dacron strip (8-mm width) was placed around the PA of the left caudal (LCa) lobe, and the ends were sutured together to achieve a predetermined circumference equal to the mean relaxed circumference of the LCa lobar PA measured at postmortem in normal adult dogs (1.8 cm) (PAB group, n = 4). Control animals underwent left thoracotomy without PA banding; the banding strip was placed around the LCa lobe PA without suturing (Sham banding, n = 4). The chest wall was closed in layers and lidocaine (1%) was applied to the intercostal nerves. A small chest tube connected to a one-way valve was placed for 24 h to prevent atelectasis. Buprenorphine was administered postoperatively for 48 h and as needed thereafter. Wound dressings were changed daily, and skin stitches were removed after 7–10 days.

Right PNX.

Following recovery 3 wk later, the animal was anesthetized, intubated, and ventilated as described above. A right lateral thoracotomy was performed through the fifth intercostal space. The lobar vessels were ligated and cut. The bronchi were stapled and the right lung was removed. The bronchial stump was immersed in warm saline to check for leaks and then oversewn with loose hilar tissue for added protection. The chest wall was closed in layers, and lidocaine (1%) was applied to the intercostal nerves. Residual thoracic air was partially evacuated to underwater seal. Rectal temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and transcutaneous O2 saturation were monitored continuously. Supplemental O2 was administered perioperatively. Intraoperative fluid administration was <50 ml. Blood loss was minimal. Postoperative care was similar to that described above.

Lung function under anesthesia.

Following established procedures (7, 8), the animal was fasted overnight, premedicated, anesthetized, intubated, and mechanically ventilated in the supine position. Esophageal and mouth pressures, rectal temperature, heart rate, and transcutaneous O2 saturation were continuously monitored. Static transpulmonary pressure (Ptp)-lung volume curves were measured using a calibrated syringe to inflate the lung with air (15, 30, 45, and 60 ml/kg) above end-expiratory lung volume (EELV) in incremental and then decremental order. Lung volume, pulmonary blood flow, lung and membrane diffusing capacity (DLCO and DMCO), pulmonary capillary blood volume (Vc), and septal tissue volume (including microvascular blood) were measured simultaneously using an established rebreathing technique (8, 35) at two inspired O2 concentrations (21 and 99%) and two lung volumes (30 and 45 ml/kg above EELV). Duplicate measurements under each condition were averaged. A venous blood sample was drawn before, in the middle, and immediately after the experiment to measure hemoglobin and carboxyhemoglobin concentrations.

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT).

In vivo imaging was performed pre-PNX and 3–4-mo post-PNX at Ptps of 10 and 30 cmH2O. The procedures have been established (38, 39, 49). Briefly, the animals were fasted overnight, premedicated, and anesthetized with an intravenous bolus of propofol and maintained with an infusion of ketamine and diazepam. The animal was intubated with a cuffed endotracheal tube, placed supine, and mechanically ventilated (tidal volume ∼10 ml/kg) to eliminate spontaneous breathing efforts. Esophageal and mouth pressures were measured simultaneously to estimate Ptp. Static pressure-lung volume relationship was verified by incrementally inflating the lung in 10-ml/kg steps from functional residual capacity using a calibrated syringe. A General Electric Lightspeed 16 scanner (1.25 × 1.25-mm collimation, 120 kV, 190 mA, pitch 1.0, and rotation time 0.8 s) was used to obtain consecutive apex-to-base images. Prior to each imaging sequence, lungs were hyperinflated with three tidal breaths, followed by passive expiration to functional residual capacity, then reinflated to the preselected Ptp (10 or 30 cmH2O) and the breath held during scanning.

Image analysis.

Each lobe was identified by fissures and analyzed separately using customized, semiautomated software (Microsoft Visual C++ 6.0) developed by us (38, 39, 49). The lobes, major airways, and blood vessels were segmented. The area occupied by the lung was outlined by attenuation thresholding, excluding trachea and the next three generations of major airways and other conducting structures larger than 1–2-mm diameter. Interlobar fissures were fitted with cubic splines. Computed tomography (CT) attenuation of extrathoracic air (−1,000 HU), water (0 HU), intrathoracic air (CTair, sampled at 5 mm above the carina, 5 mm below the endotracheal tube, and halfway between them, average −989 HU, range −1,000 to −970 HU), and tissue (CTtissue, sampled at 5 points within the right lobe of the liver, average 54 HU, range +44 to +62 HU) were used to partition the total volume of each lobe (Vlobe) into air and tissue volumes (Vair and Vtissue) by assuming that the average CT value for air-free lung tissue (including uncontrasted blood) equals that of the liver (38).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where CTlobe is average CT value (in HU) of a lobe and FTV is fractional tissue volume.

Hemodynamics, cardiac output, and lobar perfusion.

These measurements were performed pre-PNX and 3-mo post-PNX in the conscious animal standing at rest. Limited hemodynamic measurements were also obtained with the animals running on a treadmill at a low workload (6 mph, 0% grade) as tolerated. The external jugular vein was cannulated under local anesthesia. A thermodilution catheter (Criticath SP5507H, 7.5 Fr; Argon Medical Devices, Plano, TX) was inserted and advanced to the pulmonary artery (PA) under pressure monitoring.

Lobar pulmonary perfusion was measured by a fluorescent microsphere technique (11, 12, 25). Approximately 2 × 106 fluorescent microspheres (15-μm diameter; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) of one of six colors (blue, blue-green, yellow-green, red, crimson, or scarlet) were sonicated for 3 min and vortexed for 1 min, then injected via a forelimb peripheral intravenous line and flushed with saline. A reference blood sample was simultaneously withdrawn from the tip of the PA catheter at a constant rate (6.0 ml/min) for 3 min into a heparinized glass syringe. Duplicate measurements were obtained using different colored microspheres. PA pressure was monitored continuously, and triplicate cardiac output measurements were obtained by the thermodilution technique before and after each microsphere injection. Replicate measurements obtained under each condition were averaged.

Lung fixation.

Following completion of the above studies and under deep anesthesia, a tracheotomy was performed, and a cuffed endotracheal tube was inserted and tied securely. The abdomen was opened via a midline incision, and the lung was collapsed via a transdiaphragmatic incision. An overdose of pentobarbital and phenytoin was administered intravenously to stop the heart, and the remaining lobes were reinflated within the thorax by tracheal instillation of 2.5% buffered glutaraldehyde at 25 cmH2O of hydrostatic pressure above the sternum. The tracheal tube was closed to maintain airway pressure. The lungs were removed intact, immersed in buffered 2.5% glutaraldehyde, floated on a water bath, and stored at 4°C for at least 4 wk before further processing.

Estimation of lobar blood flow.

Using established techniques (11, 25), fluorescence was measured in the lobes of the right lung removed at PNX and in the fixed post-PNX left lobes removed at the terminal experiment. For the right lung, each lobe was diced into ∼1-cm cubes and blotted to remove excess fluid, and the weight was recorded. For the fixed left lung, tissue blocks were sampled for morphometry (described below), and the weight of the removed samples was recorded. The remaining lobar tissue was blotted to remove excess fluid and then diced into ∼1-cm cubes and weighed. The tissue pieces were digested by adding ethanolic KOH with 2% Tween-80. Microspheres were recovered by negative pressure filtration. Then 2-ethoxyethyl acetate (Cellosolve) (2.0 ml) was added to extract the fluorescent dye. Fluorescence was measured using a fluorimeter (Photon Technology International, Edison, NJ) and matched glass cuvettes. The sum of fluorescent signals in all samples in a given lobe (fllobe) was divided by the total fluorescence in all lobes (fltotal, 7 lobes pre-PNX, 3 lobes post-PNX) to yield the fractional lobar perfusion (fllobe/fltotal), which, when multiplied by total perfusion, yields the absolute lobar blood flow. Each lung was analyzed separately, and correction was applied for the weight of the removed tissue samples. Pilot studies verified that lung fixation prolonged the time required for tissue digestion by KOH without affecting the fluorescent signals (data not shown). Duplicate measurements under each condition were averaged.

Measurement of lobar volume.

Volume of each intact lobe was measured by saline immersion. Each lobe was serially sectioned (2-cm intervals), and the cut surfaces were photographed. Volume of each sectioned lobe was estimated by the Cavalieri principle (48); this tension-free volume was used in subsequent morphometric calculations.

Tissue sampling for morphometry.

These methods are well established (15, 36). Briefly, each lobe was sampled systematically with a random start in a stratified scheme: gross (level 1, approximately ×2), low- and high-power light microscopy (level 2, ×275; level 3, ×550, respectively), and electron microscopy (EM) (level 4, ×19,000). Standard test grids were employed at each level (15, 45). In level 1, serial sections were photographed for point counting to estimate the volume density of coarse parenchyma per unit of lung volume [Vv(cp,L)] by excluding structures >1 mm in diameter. Four blocks per lobe were sampled, postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, treated with 2% uranyl acetate, dehydrated through graded alcohol, and embedded in Spurr's resin. Each block was sectioned (1 μm) and stained (toluidine blue). In level 2, multiple sections per block and at least 20 nonoverlapping microscopic fields were systematically analyzed by point counting. Structures between 20 µm and 1 mm in diameter were excluded to estimate the volume density of fine parenchyma per unit volume of coarse parenchyma [Vv(fp,cp)]. In level 3, one section per block was analyzed, and at least 20 nonoverlapping microscopic fields per block were systematically imaged (80 images per lobe) to estimate the volume density of alveolar septa per unit volume of fine parenchyma [Vv(s,fp)] by excluding all structures >20 μm in diameter. In level 4, two blocks per lobe were sectioned (80 nm) and mounted on copper grids. At least 30 nonoverlapping EM fields per grid (60 images per lobe) were analyzed at approximately ×19,000 (JEOL EXII; JEOL, Peabody, MA). Volume densities of alveolar septal components were estimated by point counting. Alveolar epithelial and capillary surface densities (cm−1) were estimated by intersection counting. About 200–300 points or intersections were counted per grid (coefficient of variation <10%). To obtain absolute volumes and surface areas, the volume and surface densities were related through the cascade of levels to the volume of the lobe measured by the Cavalieri principle. A volume-weighted average of the entire lung was also calculated.

The prevalence of double-capillary (DblCap) profiles, a measure of new capillary formation by intussusception (3, 47), was assessed by systematically and completely sampling two grids per lobe (×1,000), and the results were expressed as a ratio of double/(single + double) capillary profiles.

Data analysis.

Where appropriate, the results (means ± SD) were expressed per kilogram of body weight. Unpaired t-test and factorial ANOVA was used to compare PAB and Sham groups. Paired t-test and repeated measures ANOVA was used to compare static Ptp-lung volume relationships, the temporal changes (pre- to post-PNX), and the results among lobes. Post hoc analysis used Fisher's protected least significant difference (PLSD) test. Morphometric results were expressed in relative and absolute terms, as ratios with respect to the mean values in the corresponding lobe of Sham-banded control group, and with respect to the mean values in the corresponding lobe of previously reported unoperated normal adult hounds (n = 6) (34). A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Physiological function under anesthesia.

Compared with Sham banding, body weight was lower in PAB group pre-PNX. Body weight did not change 3-mo post-PNX in the Sham group but increased slightly in the PAB group (Table 1). Hemoglobin concentration was modestly higher in PAB group pre- and post-PNX. Pre-PNX EELV was 17% higher with a larger post-PNX decline following PAB than Sham banding (30 vs. 14%). Pre-PNX EILV was 13% higher following PAB than Sham banding, with a larger post-PNX decline in PAB (17%) than in Sham (9%) group. Total pulmonary blood flow was similar between PAB and Sham groups both pre- and post-PNX. DLCO expressed at standard conditions and DMCO declined ∼37 and ∼40% post-PNX, respectively, in both groups. Pre-PNX Vc was 17% higher following PAB than Sham banding; post-PNX Vc declined 25% in Sham group but remained unchanged in PAB group; these results are consistent with pooling of alveolar capillary blood following PAB. Pre- to post-PNX septal tissue volume declined significantly in both Sham (25%) and PAB (16%) groups.

Table 1.

Lung function measured under anesthesia

| Pre-PNX |

Post-PNX |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHAM | PAB | SHAM | PAB | |

| Number | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Body weight, kg | 22.9 ± 1.0 | 18.5 ± 1.7* | 23.4 ± 0.6 | 19.7 ± 1.9*‡ |

| Hemoglobin while awake, g/dl | 13.3 ± 0.7 | 14.3 ± 0.5* | 13.3 ± 0.4 | 15.7 ± 1.4*‡ |

| Hemoglobin while anesthetized, g/dl | 11.8 ± 0.6 | 11.3 ± 0.4 | 12.3 ± 0.3‡ | 12.9 ± 0.7*‡ |

| End-expiratory lung volume, ml/kg | 41.5 ± 6.9 | 48.7 ± 6.6* | 35.7 ± 5.7‡ | 34.3 ± 2.6‡ |

| End-inspiratory lung volume, ml/kg | 79.7 ± 6.3 | 89.7 ± 8.3* | 72.7 ± 5.7‡ | 74.2 ± 4.1‡ |

| Specific lung compliance, ml·(cmH2O·l)−1 | 22.2 ± 5.0 | 22.2 ± 5.7 | 30.5 ± 6.9‡ | 26.2 ± 1.3 |

| Mean Pao2 during rebreathing, mmHg | 119.9 ± 3.9 | 119.9 ± 8.2 | 125.1 ± 1.5‡ | 118.8 ± 1.5* |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 152 ± 22 | 148 ± 17 | 133 ± 11‡ | 138 ± 10 |

| Pulmonary blood flow, ml/kg | 85.5 ± 13.1 | 90.5 ± 11.6 | 91.0 ± 11.9 | 85.2 ± 9.5 |

| DLCO-std, ml·(min·mmHg·kg)−1 | 0.67 ± 0.08 | 0.76 ± 0.13 | 0.43 ± 0.04‡ | 0.48 ± 0.03*‡ |

| DMCO, ml·(min·mmHg·kg)−1 | 1.13 ± 0.14 | 1.34 ± 0.41 | 0.70 ± 0.14‡ | 0.78 ± 0.20‡ |

| Pulmonary capillary blood volume, ml/kg | 2.46 ± 0.30 | 2.88 ± 0.49 | 1.84 ± 0.15‡ | 2.80 ± 1.92 |

| Septal tissue volume, ml/kg | 7.34 ± 1.54 | 6.39 ± 2.65 | 5.51 ± 1.15* | 5.39 ± 1.17 |

Values are means ± SD. PaO2, alveolar O2 tension. DLCO-std, DLCO adjusted to standard values of Hb = 14.6 g/dl and Pao2 = 120 mmHg. Inflation volume during rebreathing was 30 ml/kg. Specific compliance was calculated between 10- and 30-cmH2O transpulmonary pressure.

P ≤ 0.05 PAB vs. corresponding Sham banding by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

P ≤ 0.05 pre-PNX vs. post-PNX by two-tailed paired t-test.

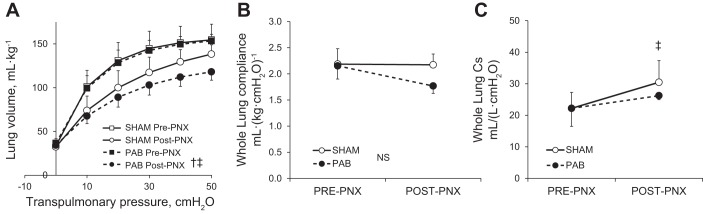

Pre-PNX static Ptp-lung volume curves were similar between PAB and Sham groups, with a larger post-PNX decrease in lung volume at a given Ptp in the PAB group (Fig. 2A). Whole lung compliance (Ptp 10–30 cmH2O) was similar pre-PNX but lower in the PAB group post-PNX (Fig. 2B). Whole lung specific compliance (Cs) increased significantly post-PNX in Sham but not in PAB group (Fig. 2C). Thus PAB impaired the post-PNX adaptive increase in Cs in the remaining lung.

Fig. 2.

Lung function measured under anesthesia pre- and post-PNX in PA-banding (PAB) and Sham-banding groups. A: static transpulmonary pressure-lung volume relationship. B: whole lung compliance. C: specific lung compliance (Cs) between 10- and 30-cmH2O transpulmonary pressure. Means ± SD. P < 0.05 by repeated measures ANOVA: †PAB vs. Sham-banding groups; ‡post- vs. pre-PNX. NS, not significantly different (P > 0.05).

Hemodynamic data.

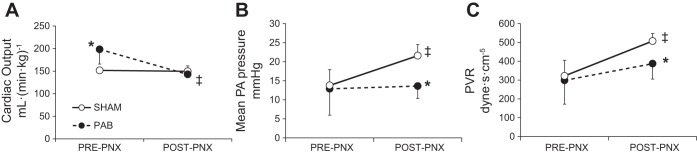

Measurements were obtained pre- and post-PNX while standing at rest (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Comparing pre- to post-PNX, heart rate did not change in Sham group but declined in PAB group. Thermodilution cardiac output was higher in PAB group pre-PNX, remaining unchanged post-PNX in Sham group but declining 28% post-PNX in PAB group (Fig. 3A). Systolic PA pressure increased similarly in both groups from pre- to post-PNX. Post-PNX diastolic PA pressure was unchanged in Sham but declined markedly in PAB group so that mean PA pressure increased in Sham but not in PAB group (Fig. 3B). Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) was not different between groups pre-PNX, although more variable in PAB group. Post-PNX PVR was more elevated in Sham than PAB animals (Fig. 3C). Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was similar between groups pre-PNX and unchanged in Sham group post-PNX (Table 2). In all PAB animals, the catheter balloon could not be wedged post-PNX. Results indicate that in PAB animals, pulmonary vasodilation and decreased cardiac output limited the post-PNX increase in PVR while standing at rest. Limited post-PNX hemodynamic data obtained upon light exercise showed exaggerated increases in systolic and mean PA pressures in PAB vs. Sham animals (103 ± 3 vs. 59 ± 15 mmHg and 46 ± 4 vs. 33 ± 9 mmHg, respectively) while diastolic PA pressure was similar (17 ± 5 vs. 19 ± 7 mmHg).

Table 2.

Hemodynamic data measured while standing at rest

| Pre-PNX |

Post-PNX |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHAM | PAB | SHAM | PAB | |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 104 ± 5 | 109 ± 5 | 102 ± 16 | 96 ± 2‡ |

| Cardiac output (thermodilution), l/min | 3.41 ± 0.29 | 3.58 ± 0.60 | 3.53 ± 0.30 | 2.80 ± 0.19‡* |

| Cardiac output (thermodilution), ml·(min·kg)−1 | 151.6 ± 7.5 | 198.2 ± 32.4* | 149.6 ± 12.1 | 142.8 ± 7.5‡ |

| Systolic PA pressure, mmHg | 24.8 ± 3.7 | 22.7 ± 6.3 | 38.3 ± 2.6‡ | 34.9 ± 3.6‡ |

| Diastolic PA pressure, mmHg | 8.3 ± 4.6 | 8.0 ± 7.5 | 13.2 ± 3.5 | 2.9 ± 3.8* |

| Mean PA pressure, mmHg | 13.8 ± 4.2 | 12.9 ± 6.9 | 21.6 ± 2.9‡ | 13.6 ± 3.2* |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance, dyne·s·cm−5 | 322.0 ± 82.8 | 298.2 ± 126.2 | 507.4 ± 40.2‡ | 387.3 ± 82.1* |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, mmHg | 5.5 ± 3.2 | 6.2 ± 6.8 | 4.6 ± 2.2 | Unable to wedge |

Values are means ± SD.

P ≤ 0.05 PAB vs. corresponding Sham banding by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

P ≤ 0.05 pre-PNX vs. post-PNX by two-tailed paired t-test.

Fig. 3.

Pulmonary hemodynamics measured while standing at rest pre- and post-PNX in PA banding (PAB) and Sham-banding groups. A: cardiac output was measured by a thermodilution technique. B: mean pulmonary arterial (PA) pressure. C: pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). Means ± SD. P < 0.05: *PAB vs. the corresponding Sham by factorial ANOVA; ‡post- vs. pre-PNX by repeated measures ANOVA.

Lobar PA perfusion.

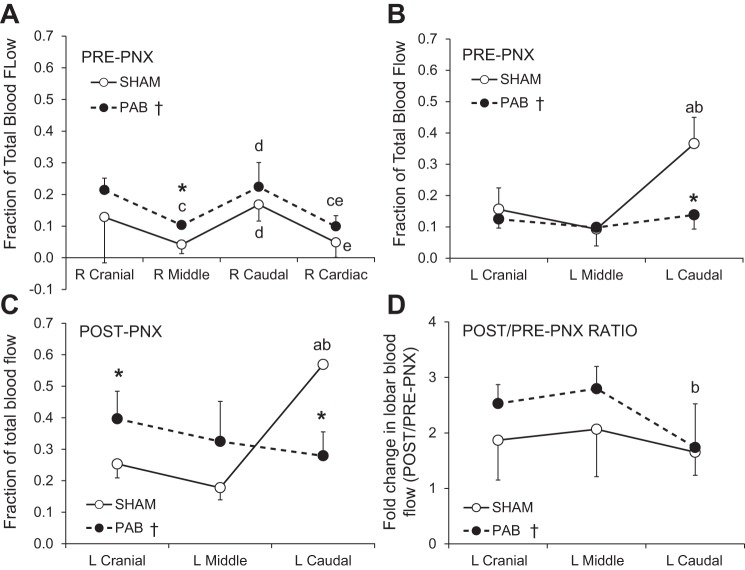

Lobar perfusion was measured pre- and post-PNX while standing at rest and expressed as a fraction of total perfusion. Cardiac output was not altered before and after microsphere injections (data not shown). Before PNX, fractional perfusion to all lobes of the right lung was higher in PAB than in Sham group (Fig. 4A) while in the left lung fractional perfusion to the banded LCa lobe was lower in PAB than Sham group but not different between groups in the unbanded left cranial (LCr) and left middle (LM) lobes (Fig. 4B). Thus PAB of the LCa lobe caused redistribution of perfusion mainly to the lobes of the right lung.

Fig. 4.

Lobar blood flow measured by a microsphere technique while standing at rest. A and B: pre-PNX blood flow to the right (A) and left (B) lung lobes expressed as fractions of total blood flow. C: post-PNX blood flow to the remaining lobes, expressed as fractions of total blood flow. D: fold change (post-PNX/pre-PNX ratio) in lobar blood flow. Means ± SD. P ≤ 0.05: *PAB vs. corresponding Sham lobe by factorial ANOVA; †PAB vs. Sham across all lobes by repeated measures ANOVA; a, vs. left (L) cranial lobe; b, vs. left middle lobe; c, vs. right (R) cranial lobe; d, vs. right middle lobe; e, vs. right caudal lobe.

Following PNX, fractional perfusion to all remaining lobes of the left lung increased in both PAB and Sham groups (Fig. 4C) compared with that pre-PNX (Fig. 4B); the fold increase (post-PNX/pre-PNX ratio) was greater in the unbanded LCr and LM lobes of PAB group than in the Sham group while the fold increase in the banded LCa lobe was similar between PAB and Sham groups (Fig. 4D). These results show that lobar PAB did not prevent the post-PNX increase in perfusion to the banded lobe, but further accentuated the post-PNX increase in perfusion to the unbanded lobes.

HRCT.

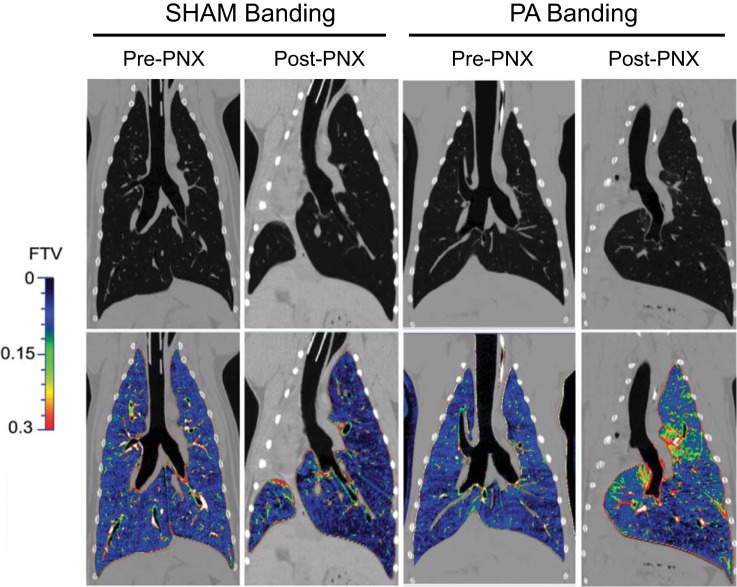

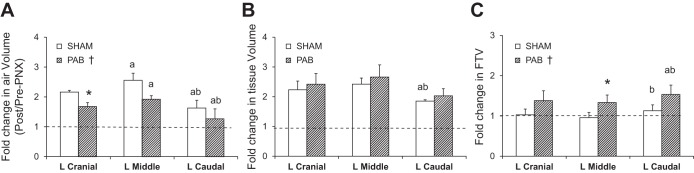

Representative images and FTV color maps of lung parenchyma and quantitative results (post-PNX/pre-PNX ratio) are shown in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively. Pre-PNX FTV distribution was similar among lobes. In Sham group, post-PNX FTV became more heterogeneous, with lower FTV in the periphery of remaining lobes and near the costophrenic angle and higher FTV in the laterally expanded part of the LCa lobe across the midline. In PAB group, post-PNX FTV distribution was further perturbed, with large heterogeneous increases in the unbanded LCr and LM lobes as well as in the laterally expanded portion of the banded LCa lobe (Fig. 5). Compared with pre-PNX (post-PNX/pre-PNX ratio of 1.0), post-PNX lobar air volume increased by 21–141% (4.3–11.2 ml/kg) in both groups, with larger increases in the unbanded LCr and LM lobes than in the banded LCa lobe (Fig. 6A). In all lobes, the increase in air volume was ∼20% less in PAB than in Sham group (P < 0.05). Post-PNX lobar tissue volumes increased 74–146% (1.0–2.5 ml/kg) in both groups (P > 0.05, Fig. 6B). Post-PNX mean lobar FTV was not significantly altered from pre-PNX in Sham animals but increased 33–54% (0.034–0.063) in PAB animals (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6C). Thus PAB altered post-PNX distributions of in vivo air, tissue and blood volumes among the remaining lobes.

Fig. 5.

Representative HRCT images (panels at top) and FTV color maps (panels at bottom) of one animal pre-PNX and post-PNX in PA-banding and Sham-banding groups.

Fig. 6.

Fold changes (post-PNX/pre-PNX ratio) in HRCT-derived parameters in the left lung lobes of PAB and Sham-banding groups: air volume (A), tissue volume (B), and FTV (C). Means ± SD. P < 0.05: *PAB vs. corresponding Sham lobe; a, vs. corresponding left cranial lobe; b, vs. corresponding left middle lobe, by factorial ANOVA and Fisher's PLSD; †PAB vs. Sham across all lobes by repeated measures ANOVA.

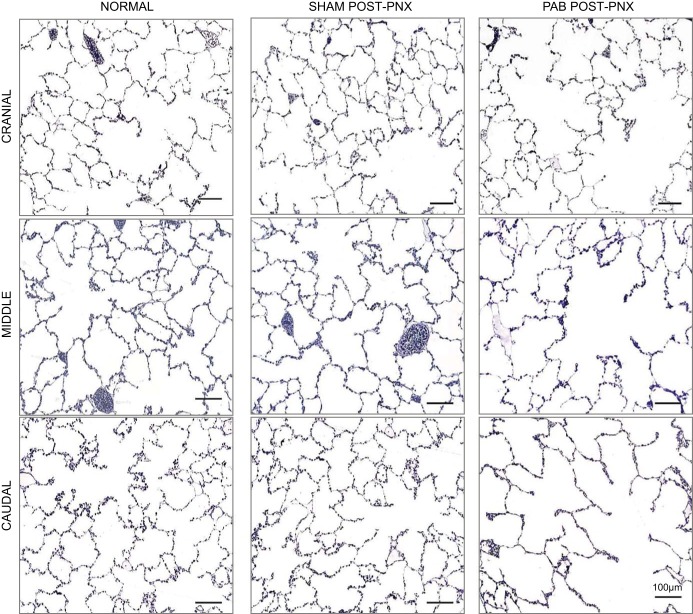

Analysis of lung structure.

Representative micrographs of post-PNX remaining lobes (Fig. 7) show normal distal lung morphology in Sham animals compared with corresponding normal (unoperated) adult canine lobes. In contrast, PAB animals showed obvious air space enlargement in all lobes. Morphometric results (Table 3) show similar morphometric hematocrit and resistance of the diffusion barrier (harmonic mean barrier thickness, τhb) between groups. Compared with Sham banding, PAB animals had a significantly smaller middle lobe, a lower volume density of fine parenchyma in all lobes, and a lower septum volume density in the banded caudal lobe. Per unit of septum volume, PAB group showed lower volume density of interstitium, primarily due to a lower volume density of collagen. Alveolar surface-to-septum volume ratio was unchanged between PAB and Sham groups, while capillary surface-to-septum volume ratio was higher in all lobes of PAB group than in corresponding Sham lobes.

Fig. 7.

Representative micrographs of post-PNX distal lung morphology in each lobe of the remaining left lung in PA-banding (PAB) and Sham-banding groups, compared with normal morphology in a separate cohort of unoperated adult animals (34). Stained with toluidine blue.

Table 3.

Morphometric measurements following right pneumonectomy

| Left Cranial Lobe |

Left Middle Lobe |

Left Caudal Lobe |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | PAB | Sham | PAB | Sham | PAB | |

| Lung volume, ml/kg | ||||||

| Immersion | 17.82 ± 4.01 | 19.21 ± 4.87 | 11.02 ± 1.33 | 9.39 ± 0.19* | 32.46 ± 2.93 | 31.11 ± 3.44 |

| Cavalieri | 15.36 ± 4.35 | 14.64 ± 3.81 | 9.42 ± 2.09 | 6.49 ± 0.56* | 27.85 ± 3.84 | 25.25 ± 3.71 |

| Morphometric hematocrit | ||||||

| Morphometric hematocrit | 0.541 ± 0.006 | 0.539 ± 0.045 | 0.555 ± 0.010 | 0.519 ± 0.061 | 0.521 ± 0.024 | 0.538 ± 0.042 |

| Harmonic mean thickness of diffusion barrier (τhb) | ||||||

| τhb, μm | 0.861 ± 0.034 | 0.821 ± 0.076 | 0.892 ± 0.019 | 0.826 ± 0.084 | 0.817 ± 0.013 | 0.788 ± 0.053 |

| Volume density per unit lung volume | ||||||

| Coarse parenchyma§ | 0.9477 ± 0.0028 | 0.9112 ± 0.0105* | 0.9553 ± 0.0137 | 0.9294 ± 0.0104* | 0.9447 ± 0.0207 | 0.9075 ± 0.0156* |

| Fine parenchyma@ | 0.9371 ± 0.0013 | 0.8892 ± 0.0094* | 0.9446 ± 0.0117 | 0.9032 ± 0.0071* | 0.9335 ± 0.0194 | 0.8919 ± 0.0132* |

| Septum† | 0.0951 ± 0.0179 | 0.0783 ± 0.0082 | 0.0963 ± 0.0336 | 0.0815 ± 0.0048 | 0.1118 ± 0.0168 | 0.0789 ± 0.0076* |

| Volume density per unit septum volume | ||||||

| Capillary blood | 0.5797 ± 0.0118 | 0.5829 ± 0.0236 | 0.5762 ± 0.0169 | 0.5915 ± 0.0101 | 0.5845 ± 0.0178 | 0.6229 ± 0.0374 |

| Septal extravascular tissue | 0.4203 ± 0.0118 | 0.4171 ± 0.0236 | 0.4238 ± 0.0169 | 0.4085 ± 0.0101 | 0.4155 ± 0.0178 | 0.3771 ± 0.0374 |

| Epithelium | 0.1543 ± 0.0030 | 0.1674 ± 0.0169 | 0.1503 ± 0.0061 | 0.1534 ± 0.0187 | 0.1519 ± 0.0057 | 0.1498 ± 0.0225 |

| Type I | 0.0967 ± 0.0037 | 0.1100 ± 0.0063* | 0.0978 ± 0.0029 | 0.1013 ± 0.0163 | 0.0925 ± 0.0060 | 0.0974 ± 0.0189 |

| Type II | 0.0577 ± 0.0054 | 0.0574 ± 0.0108 | 0.0524 ± 0.0048 | 0.0520 ± 0.0073 | 0.0594 ± 0.0087 | 0.0523 ± 0.0100 |

| Interstitium§ | 0.1636 ± 0.0037 | 0.1462 ± 0.0071* | 0.1720 ± 0.0144 | 0.1503 ± 0.0195 | 0.1612 ± 0.0156 | 0.1292 ± 0.0180* |

| Collagen@ | 0.1247 ± 0.0050 | 0.1110 ± 0.0086* | 0.1357 ± 0.0131 | 0.1066 ± 0.0119* | 0.1250 ± 0.0137 | 0.0960 ± 0.0140* |

| Cells and matrix | 0.0389 ± 0.0033 | 0.0352 ± 0.0061 | 0.0363 ± 0.0043 | 0.0437 ± 0.0101 | 0.0362 ± 0.0022 | 0.0332 ± 0.0077 |

| Endothelium | 0.1003 ± 0.0086 | 0.1024 ± 0.0096 | 0.1011 ± 0.0061 | 0.1016 ± 0.0054 | 0.1005 ± 0.0030 | 0.1024 ± 0.0026 |

| Surface density per unit septum volume | ||||||

| Alveolar surface, cm−1 | 3,955 ± 301 | 3,853 ± 476 | 3,878 ± 232 | 3,740 ± 676 | 3,813 ± 195 | 3,990 ± 354 |

| Capillary surface,† cm−1 | 4,001 ± 136 | 4,451 ± 547 | 3,828 ± 258 | 4,576 ± 438* | 4,035 ± 157 | 4,493 ± 232* |

Values are means ± SD.

P ≤ 0.05, PAB vs. Sham banding in the same lobe by two-tailed unpaired t-test. †P ≤ 0.05, §P ≤ 0.01, @P ≤ 0.001, PAB vs. Sham banding across all lobes by repeated-measures ANOVA.

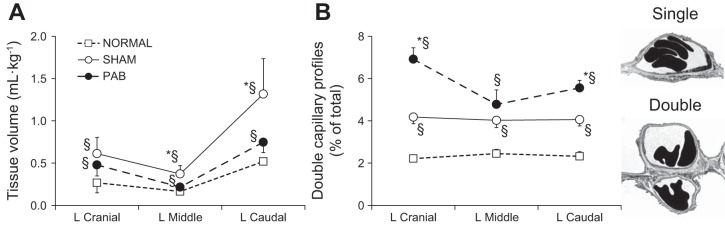

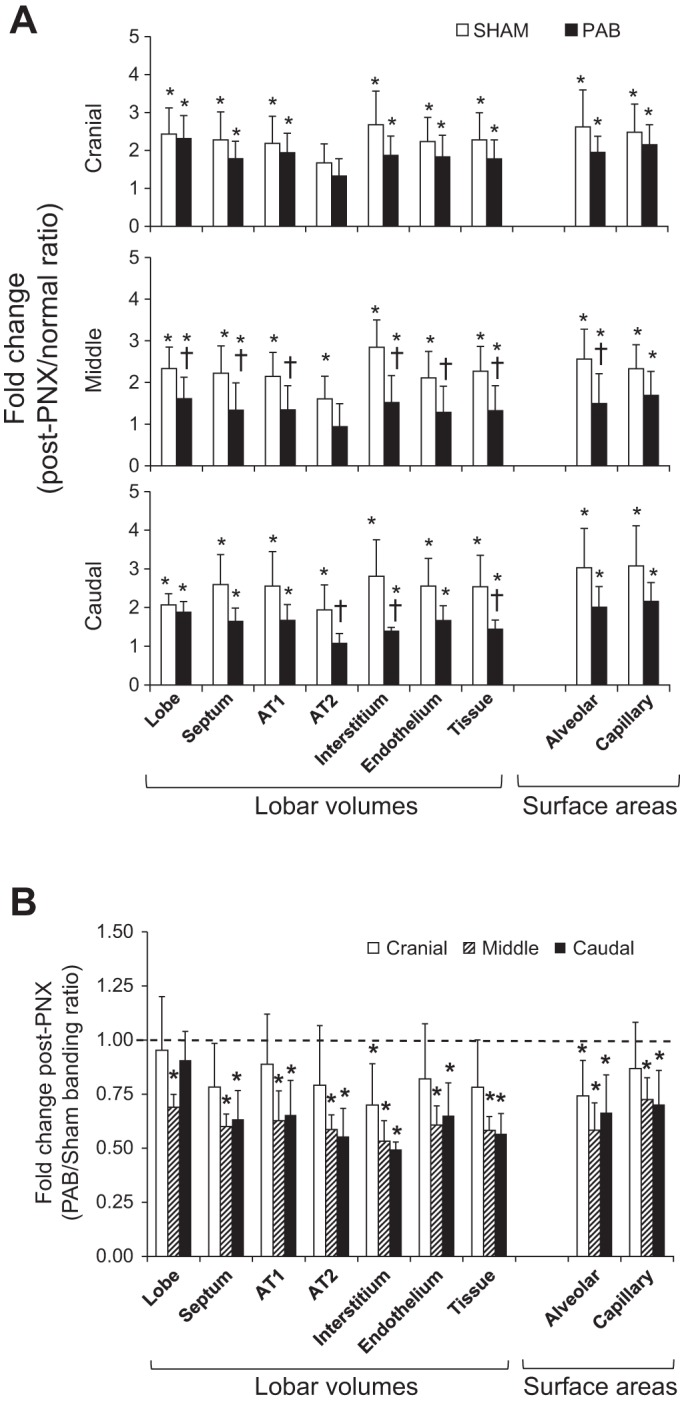

Absolute lobar septum volume was 22–40% lower in PAB than Sham group, especially in the middle (40%) and caudal (37%) lobes (Table 4). Absolute volumes of epithelium, interstitium, and endothelium were lower in all lobes of PAB animals, reaching statistical significance in the middle and caudal lobes. Absolute capillary blood volume and alveolar and capillary surface areas were also lower in PAB animals, reaching statistical significance in the middle lobe. There was a consistent pattern of lower post-PNX gain in septal structural components in the PAB group compared with the corresponding normal lobes (Fig. 8A). Compared with Sham group, the largest impairment in structural growth was seen in the PA-banded caudal lobe and the adjacent LM lobe while the LCr lobe was the least affected (Fig. 8B).

Table 4.

Absolute morphometric volumes and surface areas following right pneumonectomy

| Left Cranial Lobe |

Left Middle Lobe |

Left Caudal Lobe |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | PAB | Sham | PAB | Sham | PAB | |

| Absolute volume, ml/kg | ||||||

| Septum† | 1.46 ± 0.47 | 1.14 ± 0.30 | 0.88 ± 0.26 | 0.53 ± 0.05* | 3.16 ± 0.95 | 2.00 ± 0.42# |

| Capillary blood† | 0.8490 ± 0.2828 | 0.6650 ± 0.1672 | 0.5101 ± 0.1636 | 0.3127 ± 0.0284* | 1.8428 ± 0.5330 | 1.2551 ± 0.3158 |

| Septal extravascular tissue† | 0.6117 ± 0.1922 | 0.4780 ± 0.1340 | 0.3715 ± 0.0981 | 0.2162 ± 0.0240* | 1.3169 ± 0.4183 | 0.7467 ± 0.1228* |

| Epithelium¥ | 0.1414 ± 0.0462 | 0.1256 ± 0.0328 | 0.0859 ± 0.0231 | 0.0538 ± 0.0119* | 0.2950 ± 0.1030 | 0.1928 ± 0.0471 |

| Type I¥ | 0.0831 ± 0.0248 | 0.0657 ± 0.0229 | 0.0466 ± 0.0159 | 0.0273 ± 0.0032* | 0.1877 ± 0.0622 | 0.1040 ± 0.0244* |

| Type II† | 0.2245 ± 0.0697 | 0.1913 ± 0.0544 | 0.1325 ± 0.0389 | 0.0811 ± 0.0133* | 0.4827 ± 0.1605 | 0.2969 ± 0.0643# |

| Interstitium§ | 0.2394 ± 0.0800 | 0.1674 ± 0.0458 | 0.1497 ± 0.0343 | 0.0797 ± 0.0142* | 0.5121 ± 0.1716 | 0.2531 ± 0.0176* |

| Endothelium† | 0.1443 ± 0.0412 | 0.1184 ± 0.0368 | 0.0889 ± 0.0265 | 0.0540 ± 0.0079* | 0.3164 ± 0.0884 | 0.2058 ± 0.0479# |

| Absolute surface area, cm2/kg | ||||||

| Alveolar surface† | 5,849 ± 2,178 | 4,338 ± 961 | 3,405 ± 953 | 1,983 ± 435* | 12,134 ± 4,080 | 8,052 ± 2,130 |

| Capillary surface | 5,797 ± 1,747 | 5,032 ± 1,241 | 3,341 ± 828 | 2,421 ± 339* | 12,837 ± 4,327 | 9,012 ± 2,024 |

Values are means ± SD.

P ≤ 0.05 and #P = 0.07, PAB vs. Sham banding in the same lobe by two-tailed unpaired t-test. ¥P = 0.07,

P ≤ 0.05, and §P ≤ 0.01, PAB vs. Sham banding across all lobes by repeated measures ANOVA.

Fig. 8.

Morphometric results in the post-PNX remaining lobes of PAB and Sham-banding groups, shown as ratio with respect to the corresponding normal lobe in unoperated control animals (post-PNX/normal; A) (34), and ratio of PAB with respect to Sham banding (PAB/Sham; B). AT1 and AT2, alveolar type 1 and type 2 epithelium. Means ± SD. P < 0.05: *vs. 1.0 (the average in normal or Sham); †vs. the corresponding Sham. Factorial ANOVA.

Compared with the left lobes of unoperated normal animals, overall post-PNX gain in extravascular alveolar tissue volume was significantly diminished in PAB animals compared with Sham-banding animals (Fig. 9A). In contrast, the expected post-PNX increase in the prevalence of DblCap profiles was further exaggerated in all lobes of the PAB group, reaching statistical significance in the LCr and LCa lobes with the largest increase seen in the unbanded LCr lobe (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9.

Extravascular alveolar septal tissue volume (ml/kg; A) and prevalence of double-capillary profiles (percent of total [single + double] capillary profiles; B), in post-PNX remaining lobes of the left lung in PAB and Sham-banding groups, compared with the corresponding lobes of unoperated normal adult animals (34). Means ± SD. P < 0.05: *PAB vs. Sham; §vs. unoperated normal lobe. Factorial ANOVA. Examples of single- and double-capillary morphology are shown at right.

DISCUSSION

Summary of the main findings.

We examined the effects of redistribution of lobar perfusion on post-PNX compensatory lung growth in adult canine lungs. The main findings are as follows:

1) In PAB compared with Sham banding, pre-PNX pulmonary hemodynamics measured while standing were unaltered except for a higher cardiac output. Post-PNX cardiac output and diastolic PA pressure were reduced, which limited the post-PNX increase in PVR.

2) PAB differentially altered the distribution of pulmonary blood volume and flow. In the banded LCa lobe, pre-PNX perfusion was reduced without a change in cardiac output. Following PNX, the banded LCa lobe experienced a perfusion increase (1.74-fold) similar to that in the Sham-banded LCa lobe (1.65-fold, P > 0.05) whereas the unbanded LCr and LM lobes experienced larger increases in perfusion (2.5–2.8-fold) than their corresponding Sham-banded lobes (1.9–2.1-fold). Thus PAB exaggerated the post-PNX perfusion gradient between banded and unbanded lobes.

3) PAB impaired post-PNX expansion of the remaining lung and blunted the increase in specific lung compliance. These changes were associated with distal air space enlargement and diminished structural gain in the volumes and surface areas of alveolar septal tissue components in all lobes; impairment was greater in the banded LCa lobe and its adjacent LM lobe than in the LCr lobe.

4) In contrast to the impairment of post-PNX extravascular alveolar septal tissue growth, PAB significantly enhanced the expected post-PNX increase in DblCap formation in both banded and unbanded lobes, consistent with perfusion-related stimulation of intussusceptive alveolar angiogenesis.

These results show that lobar perfusion plays an important role in modulating post-PNX compensatory lung growth, with differential effects on extravascular alveolar tissue growth and new capillary formation.

Critique of the methods.

Normally, the right lung constitutes 55–58% and the left lung constitutes 42–45% of total lung volume with a similar partition of ventilation and perfusion. Before PNX in Sham-banding group, fractional perfusion to the left lung (∼60% of total) was higher than that to the right lung (∼40%) because of a high fractional perfusion to the LCa lobe, which most likely reflects local reaction to the presence of the banding material. In the PAB group, perfusion to the left and right lungs was ∼40 and ∼60%, respectively, of total, reflecting a shift away from the operated left lung to the unperturbed right lung. The post-PNX increase in perfusion to the LCa lobe (1.65-fold) was slightly less than that to the other remaining lobes (1.87- and 2.07-fold) even in Sham banding animals. There was no significant systemic inflammation as circulating white blood cell counts were within normal range (data not shown). Local inflammatory effects should be similar between PAB and Sham-banding groups.

The pulmonary artery of LCa lobe was banded to its average normal relaxed circumference measured postmortem in adult dogs; PAB reduced baseline (pre-PNX) fractional perfusion to LCa lobe but did not alter the fold increase in its perfusion post-PNX, which was similar to that in the Sham-banded lobe (Fig. 4D). Thus the LCa lobe was not ischemic following PAB and remained capable of accommodating large increases in perfusion. The reduction in fractional perfusion to the LCa lobe was redistributed mainly to the right lung. In contrast, post-PNX perfusion to the two unbanded remaining lobes (LCr and LM) was 35% higher than that in the matched Sham lobes, indicating redistribution of the increase in perfusion to the remaining unbanded lobes; therefore PA banding exaggerated the post-PNX differential in perfusion change among banded and unbanded lobes.

Sources of post-PNX lung growth and compensation.

The large post-PNX increases in lung volume ventilation, and perfusion elicit adaptation via several mechanisms: 1) recruitment of remaining alveolar microvascular reserves, 2) remodeling of existing gas exchange structures, and 3) growth of new alveolar tissue and capillaries. Microvascular recruitment is evident from a linear increase in diffusing capacity as pulmonary blood flow and volume increase (23, 26), which maintains the diffusion-perfusion (DL/Q̇) ratio and optimizes end-capillary O2 saturation (14). Alveolar surfaces unfold while capillaries open and distend, so that effective gas exchange surfaces and diffusing capacity per unit of lung are higher than that expected on the basis of anatomical loss of lung units. Remodeling occurs early post-PNX with air space expansion followed by rearrangement of septal constituents (2, 4) and lengthening of interalveolar septa. Combined with recruitment of epithelial and capillary surfaces and surfactant, these changes augment gas exchange in the remaining lung even without the generation of new gas exchange units (5, 21) Reinitiation of alveolar growth occurs preferentially in the infracardiac lobe following 42% lung resection and in all of the remaining lobes following 58% resection (37). Newly formed tissue and capillaries undergo remodeling over several months to partially normalize lung structure and function. The slow and ultimately incomplete compensatory response in adult lungs contrasts with that in young canines where vigorous post-PNX growth completely normalizes alveolar gas exchange and aerobic capacity (40), although significant bronchovascular mechanical abnormalities remain. Thus developmental signals intensify the post-PNX signals for alveolar growth, indicating that independent growth signals are additive or synergistic.

Expansion-related signals for growth and compensation.

Using custom-shaped inflatable silicone prosthesis to reversibly prevent lateral expansion of the remaining lung following PNX and temporally separate expansion-related from perfusion-related signals, we estimated that parenchyma expansion explains 40–70% of the observed structural and functional compensation (9, 17, 19, 36, 46). In animals with inflated prosthesis, the remaining lung showed alveolar septal crowding, capillary congestion, and diminished gains in cell volumes and gas exchange surface areas compared with animals with deflated prosthesis where the remaining lung was allowed to expand across the midline (19). Activation of growth regulators such as hypoxia-inducible factor family members, paracrine erythropoietin receptor, and VEGF receptor was also diminished (51). Delayed post-PNX deflation of an inflated prosthesis led to progressive increases in lung volume and DLCO over several months, i.e., “catch-up” adaptation (9, 46). Even without lateral expansion, with inflated prosthesis the remaining lung elongated by caudal displacement of the diaphragm and by widening the rib cage (46), which accounted for a residual 20–30% increase in air and tissue volume compared with the corresponding normal lung. Thus the post-PNX remaining lung did not expand just to fill space, but grew even when space was not readily available, suggesting a role for non-expansion-related growth stimuli.

Perfusion-related signals for growth and compensation.

Both pulmonary blood flow and pulmonary capillary blood volume per unit of lung increase following PNX (23). Post-PNX PA pressure may be normal at rest but elevated upon exercise (20, 41). Increased mechanical strain/shear on endothelial cells not only stimulates gene expression (6) but also increases generation of reactive oxygen species (1, 44) and can predispose to microvascular leakage and dysfunction. In the newborn pig, ligation of one PA increases perfusion to, and augments growth of, the contralateral lung (13). In contrast, pulmonary capillary congestion in chronic heart failure causes thickening of the alveolar endothelium, epithelium, and basement membrane (24, 43), which impedes gas diffusion. Only one study has attempted to directly alter perfusion post-PNX by banding one lobar PA in ferrets and showed no effect of PA banding on post-PNX DNA and protein content of either the banded or the unbanded lobes (32); however, lobar perfusion and alveolar structure and function were not assessed in that study.

In our animals, PAB reduced baseline perfusion to the banded LCa lobe and redirected flow to the right lung without affecting cardiac output or pulmonary hemodynamics at rest. Following subsequent PNX, the expected perfusion increase to the unbanded remaining lobes was exaggerated while perfusion to the banded lobe increased similarly to that in Sham controls. The post-PNX perfusion changes measured by microspheres are consistent with HRCT results showing redistribution of pulmonary tissue-and-blood volume to the unbanded remaining lobes, resulting in heterogeneous increases of regional FTV.

Selective lobar PA banding impaired post-PNX lung expansion, blunted the increase in specific lung compliance, and reduced the gains in extravascular alveolar tissue volumes and surface areas in all remaining lobes; average impairment ranged from ∼11 to 50% (compared with Sham-banding controls). The banded LCa lobe exhibited the greatest impairment, and the unbanded LCr lobe exhibited the least impairment. Structural responses in the small, unbanded LM lobe were impaired to an extent similar to that in the banded LCa lobe. The LM lobe, also termed the inferior segment of the LCr lobe, is often incompletely separated from the larger superior segment of LCr lobe. We analyzed the LM lobe separately as its responses were distinct from that of the LCr lobe (superior segment) and more similar to that of the LCa lobe. This finding may be related to the physical proximity of the LM lobe to the banding site. The origin of the PA to the LM lobe arises from the main trunk not far from the site of banding. If PAB of LCa lobe had caused turbulent flow upstream, the impact may be greater on the LM lobe than on the more distant LCr lobe.

Perfusion-stimulated double-capillary formation.

Unexpectedly, PAB significantly enhanced the post-PNX increase in DblCap profiles, an indicator of intussusceptive angiogenesis (3, 18). Intussusception is an important mechanism of postnatal capillary formation whereby physical stress imposed on elastic fibers in a sheet-flow alveolar capillary network lifts a tissue pillar into an existing capillary lumen, eventually transecting it (18) and forming the DblCap profiles. With subsequent remodeling the septa lengthen and the DblCaps separate into two single capillaries resulting in an increase in total gas exchange surface area. While DblCaps predominate in fetal lungs, their prevalence decreases after birth (∼5 and ∼2% of total alveolar capillary profiles in canine lungs by 3 mo and 1 yr of age, respectively). We observed a progressive increase in the prevalence of DblCaps in adult canine lungs correlated to loss of lung units. Following 42% lung resection and in the absence of compensatory growth in most of the remaining lobes, DblCap prevalence was unchanged from normal (37). Following 58% resection where all remaining lobes undergo compensatory growth, DblCaps increased significantly and the increase was further augmented by supplementation of all-trans retinoic acid (35, 47). Following 70% resection, DblCaps increased further independent of the degree of extravascular alveolar tissue growth (37), suggesting the existence of separate stimuli for tissue vs. capillary growth. Altering perfusion signals selectively enhanced post-PNX DblCap formation, which may reflect adaptive response to impairment of alveolar tissue growth. A longer follow-up period will be needed to determine whether these newly formed DblCaps remodel into single capillaries.

Conclusions.

Redistributing pulmonary perfusion by selective lobar PAB impairs post-PNX growth of alveolar tissue and gas exchange surface areas while stimulating intussusceptive capillary formation in all remaining lobes; these findings confirm the existence of independent tissue vs. capillary stimuli for compensatory lung regrowth. In vivo perfusion-related signals are complex, involving mechanical stress on the endothelium and microvascular wall, increased turbulence, reflex hemodynamic adjustment, and recruitment of neural feedback and chemical mediators. While it will be difficult in the intact animal to cleanly separate individual signals beyond that accomplished in this study, we can conclude that perfusion redistribution following loss of lung units constitutes a major stimulus separate from lung expansion-related stimuli for growth and compensation of the remaining lung units. Average impairment in post-PNX extravascular tissue growth (35–50%) in the PAB group was in a range similar to that observed previously following restriction of post-PNX lung expansion (9, 17, 19, 36, 46). That is, lung expansion and increased perfusion contribute about equally to, and together could fully account for, the post-PNX compensatory response. These results provide fundmental insight directly impacting the design of translational interventions aimed at maximally exploiting the innate potential for growth and compensation in the remaining functional lung units in chronic destructive lung disease.

GRANTS

The research was supported by Grants R01 HL040070 and UO1 HL111146 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or of the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.C.H. conceived and designed the research. D.M.D., C.Y., D.G., R.I., P.R., A.S.E., and C.C.H. performed experiments; D.M.D., C.Y., P.R., and C.C.H. analyzed data; D.M.D., C.Y., P.R., and C.C.H. interpreted results and prepared figures; D.M.D., P.R., and C.C.H. drafted, edited and revised manuscript, and approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Matthew Riegel, Angela Guillory, and the staff of the Animal Resources Center for veterinary assistance and Gregory Horton and Dr. Roderick McColl of the Department of Radiology for assistance with HRCT.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdulnour RE, Peng X, Finigan JH, Han EJ, Hasan EJ, Birukov KG, Reddy SP, Watkins JE III, Kayyali US, Garcia JG, Tuder RM, Hassoun PM. Mechanical stress activates xanthine oxidoreductase through MAP kinase-dependent pathways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L345–L353, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger LC, Burri PH. Timing of the quantitative recovery in the regenerating rat lung. Am Rev Respir Dis 132: 777–783, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burri PH. Structural aspects of postnatal lung development: alveolar formation and growth. Biol Neonate 89: 313–322, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burri PH, Pfrunder HB, Berger LC. Reactive changes in pulmonary parenchyma after bilobectomy: a scanning electron microscopic investigation. Exp Lung Res 4: 11–28, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlin JI, Hsia CC, Cassidy SS, Ramanathan M, Clifford PS, Johnson RL Jr. Recruitment of lung diffusing capacity with exercise before and after pneumonectomy in dogs. J Appl Physiol 70: 135–142, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Fabry B, Schiffrin EL, Wang N. Twisting integrin receptors increases endothelin-1 gene expression in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 280: C1475–C1484, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dane DM, Johnson RL Jr, Hsia CCW. Dysanaptic growth of conducting airways after pneumonectomy assessed by CT scan. J Appl Physiol 93: 1235–1242, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dane DM, Yan X, Tamhane RM, Johnson RL Jr, Estrera AS, Hogg DC, Hogg RT, Hsia CCW. Retinoic acid-induced alveolar cellular growth does not improve function after right pneumonectomy. J Appl Physiol 96: 1090–1096, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dane DM, Yilmaz C, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Separating in vivo mechanical stimuli for postpneumonectomy compensation: physiological assessment. J Appl Physiol (1985) 114: 99–106, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez LG, Le Cras TD, Ruiz M, Glover DK, Kron IL, Laubach VE. Differential vascular growth in postpneumonectomy compensatory lung growth. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 133: 309–316, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fluorescent Microsphere Resource Center. Manual for Using Fluorescent Microspheres to Measure Regional Organ Perfusion Online] Seattle, WA: Univ. of Wash; http://fmrc.pulmcc.washington.edu/DOCUMENTS/FMRCMAN.pdf [2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glenny RW, Bernard S, Brinkley M. Validation of fluorescent-labeled microspheres for measurement of regional organ perfusion. J Appl Physiol 74: 2585–2597, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haworth SG, McKenzie SA, Fitzpatrick ML. Alveolar development after ligation of left pulmonary artery in newborn pig: clinical relevance to unilateral pulmonary artery. Thorax 36: 938–943, 1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsia CC. Recruitment of lung diffusing capacity: update of concept and application. Chest 122: 1774–1783, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsia CC, Hyde DM, Ochs M, Weibel ER. An official research policy statement of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society: standards for quantitative assessment of lung structure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 181: 394–418, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsia CC, Johnson RL Jr. Further examination of alveolar septal adaptation to left pneumonectomy in the adult lung. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 151: 167–177, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsia CC, Johnson RL Jr, Wu EY, Estrera AS, Wagner H, Wagner PD. Reducing lung strain after pneumonectomy impairs oxygen diffusing capacity but not ventilation-perfusion matching. J Appl Physiol 95: 1370–1378, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsia CC, Ravikumar P. Role of mechanical stress in lung repair and regeneration. In: Stem Cells in the Lung, edited by Bertoncello I. New York: Humana, 2015, p. 191–212. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsia CC, Wu EY, Wagner E, Weibel ER. Preventing mediastinal shift after pneumonectomy impairs regenerative alveolar tissue growth. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281: L1279–L1287, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsia CCW, Carlin JI, Cassidy SS, Ramanathan M, Johnson RL Jr. Hemodynamic changes after pneumonectomy in the exercising foxhound. J Appl Physiol 69: 51–57, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsia CCW, Carlin JI, Wagner PD, Cassidy SS, Johnson RL Jr. Gas exchange abnormalities after pneumonectomy in conditioned foxhounds. J Appl Physiol 68: 94–104, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsia CCW, Herazo LF, Fryder-Doffey F, Weibel ER. Compensatory lung growth occurs in adult dogs after right pneumonectomy. J Clin Invest 94: 405–412, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsia CCW, Herazo LF, Ramanathan M, Johnson RL Jr. Cardiopulmonary adaptations to pneumonectomy in dogs. IV: Membrane diffusing capacity and capillary blood volume. J Appl Physiol 77: 998–1005, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang W, Kingsbury MP, Turner MA, Donnelly JL, Flores NA, Sheridan DJ. Capillary filtration is reduced in lungs adapted to chronic heart failure: morphological and haemodynamic correlates. Cardiovasc Res 49: 207–217, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hubler M, Souders JE, Shade ED, Hlastala MP, Polissar NL, Glenny RW. Validation of fluorescent-labeled microspheres for measurement of relative blood flow in severely injured lungs. J Appl Physiol 87: 2381–2385, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson RL Jr, Heigenhauser GJF, Hsia CCW, Jones NL, Wagner PD. Determinants of gas exchange and acid-base balance during exercise. Compr Physiol Suppl 29: 515–584, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaza AK, Cope JT, Fiser SM, Long SM, Kern JA, Tribble CG, Kron IL, Laubach VE. Contrasting natures of lung growth after transplantation and lobectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 123: 288–294, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kho AT, Liu K, Visner G, Martin T, Boudreault F. Identification of dedifferentiation and redevelopment phases during postpneumonectomy lung growth. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 305: L542–L554, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landesberg LJ, Ramalingam R, Lee K, Rosengart TK, Crystal RG. Upregulation of transcription factors in lung in the early phase of postpneumonectomy lung growth. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281: L1138–L1149, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langston C, Sachdeva P, Cowan MJ, Haines J, Crystal RG, Thurlbeck WM. Alveolar multiplication in the contralateral lung after unilateral pneumonectomy in the rabbit. Am Rev Respir Dis 115: 7–13, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McBride JT. Postpneumonectomy airway growth in the ferret. J Appl Physiol 58: 1010–1014, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McBride JT, Kirchner KK, Russ G, Finkelstein J. Role of pulmonary blood flow in postpneumonectomy lung growth. J Appl Physiol 73: 2448–2451, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rannels DE. Role of physical forces in compensatory growth of the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 257: L179–L189, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ravikumar P, Bellotto DJ, Johnson RL Jr, Hsia CC. Permanent alveolar remodeling in canine lung induced by high-altitude residence during maturation. J Appl Physiol 107: 1911–1917, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ravikumar P, Dane DM, McDonough P, Yilmaz C, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Long-term post-pneumonectomy pulmonary adaptation following all-trans-retinoic acid supplementation. J Appl Physiol 110: 764–773, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ravikumar P, Yilmaz C, Bellotto DJ, Dane DM, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Separating in vivo mechanical stimuli for postpneumonectomy compensation: imaging and ultrastructural assessment. J Appl Physiol (1985) 114: 961–970, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ravikumar P, Yilmaz C, Dane DM, Bellotto DJ, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Defining a stimuli-response relationship in compensatory lung growth following major resection. J Appl Physiol (1985) 116: 816–824, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravikumar P, Yilmaz C, Dane DM, Johnson RL Jr, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Regional lung growth following pneumonectomy assessed by computed tomography. J Appl Physiol 97: 1567–1574, discussion 1549, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ravikumar P, Yilmaz C, Dane DM, Johnson RL Jr, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Developmental signals do not further accentuate nonuniform postpneumonectomy compensatory lung growth. J Appl Physiol 102: 1170–1177, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takeda S, Hsia CC, Wagner E, Ramanathan M, Estrera AS, Weibel ER. Compensatory alveolar growth normalizes gas-exchange function in immature dogs after pneumonectomy. J Appl Physiol (1985) 86: 1301–1310, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takeda S, Ramanathan M, Estrera AS, Hsia CCW. Postpneumonectomy alveolar growth does not normalize hemodynamic and mechanical function. J Appl Physiol 87: 491–497, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takeda S, Wu EY, Ramanathan M, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Temporal course of gas exchange and mechanical compensation after right pneumonectomy in immature dogs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 80: 1304–1312, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Townsley MI, Fu Z, Mathieu-Costello O, West JB. Pulmonary microvascular permeability: responses to high vascular pressure after induction of pacing-induced heart failure in dogs. Circ Res 77: 317–325, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vion AC, Birukova AA, Boulanger CM, Birukov KG. Mechanical forces stimulate endothelial microparticle generation via caspase-dependent apoptosis-independent mechanism. Pulm Circ 3: 95–99, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weibel ER. Morphometric and stereological methods in respiratory physiology, including fixation techniques. In: Techniques in the Life Sciences: Respiratory Physiology, edited by Otis AB. New York: Elsevier, 1984, p. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu EY, Hsia CC, Estrera AS, Epstein RH, Ramanathan M, Johnson RL Jr. Preventing mediastinal shift after pneumonectomy does not abolish physiological compensation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 89: 182–191, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yan X, Bellotto DJ, Foster DJ, Johnson RL Jr, Hagler HH, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Retinoic acid induces nonuniform alveolar septal growth after right pneumonectomy. J Appl Physiol 96: 1080–1089, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yan X, Polo Carbayo JJ, Weibel ER, Hsia CC. Variation of lung volume after fixation when measured by immersion or Cavalieri method. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 284: L242–L245, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yilmaz C, Ravikumar P, Dane DM, Bellotto DJ, Johnson RL Jr, Hsia CC. Noninvasive quantification of heterogeneous lung growth following extensive lung resection by high-resolution computed tomography. J Appl Physiol 107: 1569–1578, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yilmaz C, Tustison NJ, Dane DM, Ravikumar P, Takahashi M, Gee JC, Hsia CC. Progressive adaptation in regional parenchyma mechanics following extensive lung resection assessed by functional computed tomography. J Appl Physiol 111: 1150–1158, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Q, Bellotto DJ, Ravikumar P, Moe OW, Hogg RT, Hogg DC, Estrera AS, Johnson RL Jr, Hsia CC. Postpneumonectomy lung expansion elicits hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L497–L504, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Q, Zhang J, Moe OW, Hsia CC. Synergistic upregulation of erythropoietin receptor (EPO-R) expression by sense and antisense EPO-R transcripts in the canine lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 7612–7617, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]