Abstract

Background and purpose

Aseptic loosening is a major cause of failure in total ankle arthroplasty (TAA). In contrast to other total joint replacements, large periarticular cysts (ballooning osteolysis) have frequently been observed in this context. We investigated periprosthetic tissue responses in failed TAA, and performed an element analysis of retrieved tissues in failed TAA.

Patients and methods

The study cohort consisted of 71 patients undergoing revision surgery for failed TAA, all with hydroxyapatite-coated implants. In addition, 5 patients undergoing primary TAA served as a control group. Radiologically, patients were classified into those with ballooning osteolysis and those without, according to defined criteria. Histomorphometric, immunohistochemical, and elemental analysis of tissues was performed. Von Kossa staining and digital microscopy was performed on all tissue samples.

Results

Patients without ballooning osteolysis showed a generally higher expression of lymphocytes, and CD3+, CD11c+, CD20+, and CD68+ cells in a perivascular distribution, compared to diffuse expression. The odds of having ballooning osteolysis was 300 times higher in patients with calcium content >0.5 mg/g in periprosthetic tissue than in patients with calcium content ≤0.5 mg/g (p < 0.001).

Interpretation

There have been very few studies investigating the pathomechanisms of failed TAA and the cause-effect nature of ballooning osteolysis in this context. Our data suggest that the hydroxyapatite coating of the implant may be a contributory factor.

Total ankle arthroplasty (TAA), which was first attempted in the 1970s, is a well-accepted treatment method for posttraumatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoarthritis of the ankle joint. Nowadays, three-part mobile-bearing systems have been established and the number of TAAs implanted is rising. However, the outcomes of primary implantation still remain less than satisfactory. Revision rates of more than 20% at 5 years and more than 40% at 10 years have been reported in registry data (Labek et al. 2011). The major cause of failure is aseptic loosening. In contrast to other total joint replacements, large periarticular cystic cavities have been observed during revision surgery in failed TAA, so-called “ballooning osteolysis”. Varying incidences of between 1% and 15% have been reported (Bonnin et al. 2004, Buechel and Pappas 2004, Hintermann et al. 2004, Knecht et al. 2004, Kofoed 2004, Valderrabano et al. 2004, Doets et al. 2006, Wood et al. 2008). Rodriguez et al. (2010) hypothesized that cyst formation is comparable to the development of osteochondral lesions, possibly based on a sort of synovial inclusion. In contrast to this, Bonnin et al. (2011) suggested that some of the cysts might have evolved from pre-existing arthritic cysts. Jacobs et al. (2006) hypothesized that cyst formation may be related to overwhelming of a local afferent transport mechanism with wear particles, resulting in an accumulation of wear particles in periprosthetic tissue. A recent study by von Wijngaarden et al. (2015) indicated that polyethylene is not the cause of osteolysis in failed TAA. Dalat et al. (2013) proposed that delamination of the coating and foreign-body reaction to wear particles may be the result of insufficient primary fixation.

Histologically, periprosthetic tissue responses have been best characterized in failed total hip arthroplasties and metal-on-metal (MoM) failures. Tissue responses can generally be described as being macrophage-dominated and/or lymphocyte-dominated. The latter represents a T-cell-mediated response comprising diffuse and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates. These tissue responses are adaptive, are characterized by immunological memory, and may resemble a type-IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction. Periprosthetic tissue responses are not well understood in ballooning osteolysis in failed TAA.

We investigated the periprosthetic tissue responses in 71 failed TAAs, and performed an element analysis in periprosthetic tissues from failed TAA.

Patients and methods

Between 2002 and 2013, 71 patients who underwent revision surgery for failed TAA (aseptic loosening) were included in the study. Preoperatively, conventional weight-bearing anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the ankle joint were evaluated for the presence of periprosthetic cysts. We defined periprosthetic cysts as being well-demarcated, periprosthetic lucencies without osseous trabeculae (Puri et al. 2002). In cases of marked ballooning osteolysis on standard radiographs (n = 31), an additional computed tomography (CT) scan with metal artefact-reducing protocol was performed. The scanned area included the whole implant and the bone-implant interface. 40 patients had no periprosthetic cysts and 31 patients had cysts, which were documented preoperatively using CT scans. All patients had undergone primary surgery for osteoarthritis; patients with known inflammatory arthritis were not included. At the time of revision surgery, infection was ruled out by laboratory blood analysis and microbiological testing of 3 intraoperative tissue specimens that were sent for aerobic and anaerobic culture. In addition, 5 patients undergoing primary total ankle replacement served as a control group for tissue analysis (Table). The implants used included STAR (Small Bone Innovations Inc., Morrisville, PA), HINTEGRA (Newdeal France and International, Lyon, France), SALTO (Tornier, Stafford, TX) and TARIC (Implantcast, Buxtehude, Germany). All of the implants used had hydroxyapatite coating, but none of them had a single-coated design. In patients with ballooning osteolysis, intraoperative tissue was obtained from curettage of the cyst cavity, including the cyst contents and wall. Multiple periprosthetic tissue samples were harvested for histological and bacteriological analyses. In the control group, multiple samples of the pseudocapsule and synovium were obtained in a standardized way, which ensured consistency of sampling. These tissues were analyzed in a manner identical to that used for the cyst samples.

Histomorphometric examination of the tissue samples was performed according to routine tissue processing protocols. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was used to visualize tissue and cellular detail. An identical set of tissue specimens was stained with van Kossa, to visualize calcium deposits. Microscopic images were obtained with a digital microscope. Points of navigation were created and a merge program was used to translate single images to a cumulative picture for each histological slide. A target area was created for marking the whole sample and an extraction area was used to specifically mark calcium deposits which appeared as black areas. The results were directly compared with hematoxylin-eosin stained slides of identical specimens. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using anti-CD3, anti-CD11(c), anti-CD20, and anti-CD68 antibodies to determine the immunophenotype of inflammatory cells. All slides were analyzed and scored semi-quantitatively by 2 independent reviewers using the modified Willert score (Willert et al. 2005). For the 2 reviewers, weighted kappa for the modified Willert score ranged from 0.93 to 0.98, indicating excellent agreement. The modified Willert score semi-quantifies adverse tissue responses according to (1) no or isolated presence of lymphocytes, (2) a few lymphocytes in some spots, (3) obvious accumulation of lymphocytes, (4) tissue loaded or overloaded with lymphocytes, dominating the structures everywhere. Tissues were observed and graded separately for (1) diffuse/overall, and (2) perivascular type of distribution of lymphocytes according to the amount per field of view using magnifications of ×40 and ×4, respectively. Similarly, T-lymphocytes (CD3+), B-lymphocytes (CD20+), macrophages (CD68+), and dendritic cells (CD11c+) were analyzed.

The metal content of the periprosthetic tissues was measured in all patients undergoing revision surgery. All tissues were dried over 6 days at room temperature to constant weight, and treated with 65% nitric acid and 30% hydrogen peroxide in a microwave oven (EN ISO 13805:2002). The dissolved tissues were analyzed with inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICPMS) (EN ISO 11885:2209) for cobalt (Co), chromium (Cr), nickel (Ni), molybdenum (Mo), titanium (Ti), iron (Fe), calcium (Ca), phosphate (P), and cadmium (Cd). The results were normalized per gram of tissue.

Statistics

SPSS version 19.0 was used for statistical analysis. ANOVA was used to analyze the data. In addition, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for having ballooning osteolysis were calculated, comparing the calcium content in periprosthetic tissue. Any p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

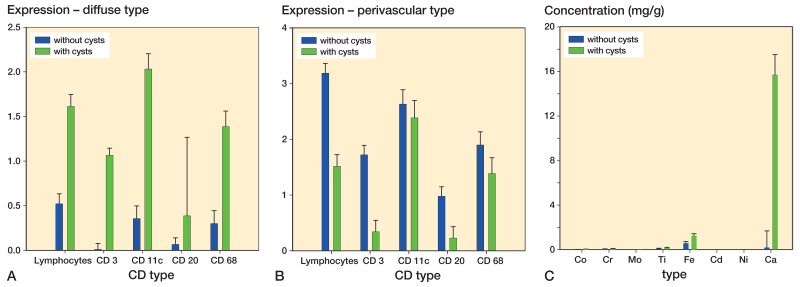

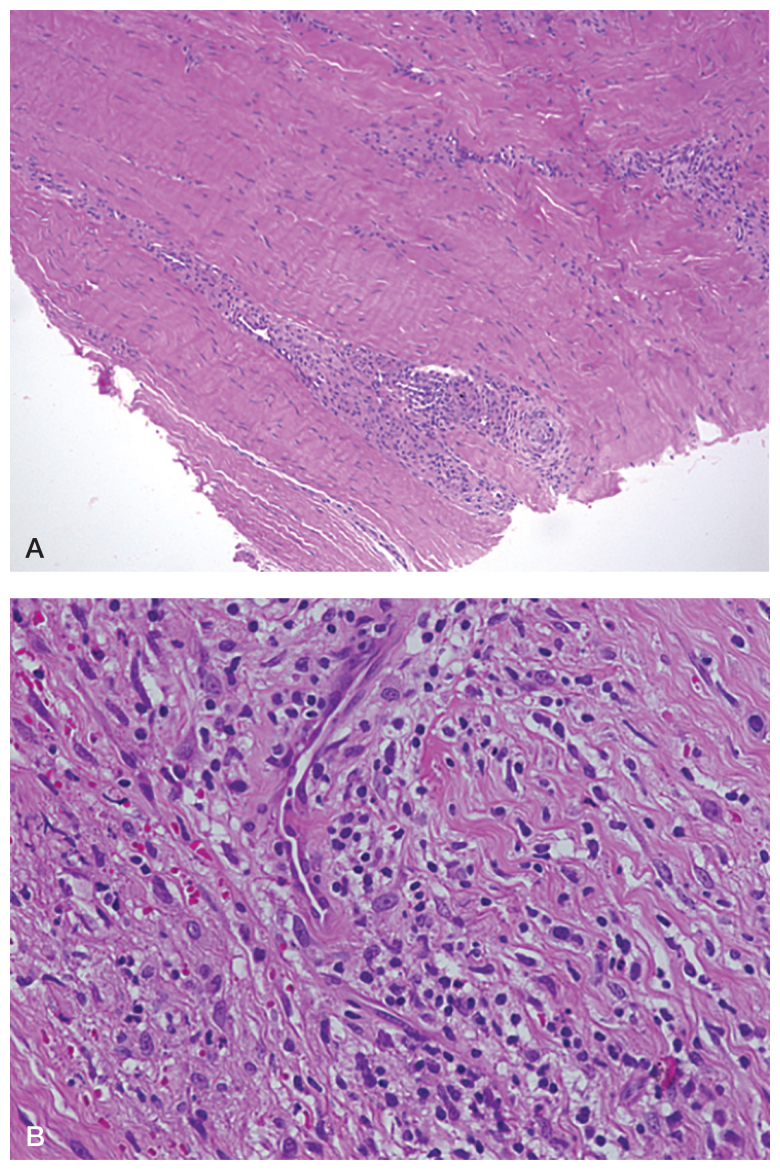

Histology showed that samples from patients with ballooning osteolysis mostly had necrotic and acellular areas. Immunohistochemistry showed that according to the modified Willert score, patients with ballooning osteolysis had an overall higher diffuse expression of lymphocytes, CD3-positive cells, CD11c-positive cells, CD20-positive cells, and CD68-positive cells than patients without ballooning osteolysis (Figure 1A). The greatest differences in the distribution of tissue reaction were seen for lymphocytes, CD3-positive cells, and CD20-positive cells (p < 0.001) (Figure 1B). Perivascular infiltration by lymphocytes is shown in Figure 2. We found a correlation between immunophenotype expression, location, and the presence of ballooning osteolysis—demonstrated by a statistically significant 3-way interaction (p = 0.002). No statistically significant correlation between periarticular cyst location and metal type was found (p = 0.8). Also, there was no statistically significant correlation between prosthesis type and metal type (p = 0.6). Von Kossa staining clearly showed black or brown-black calcium deposits (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Distribution of lymphocytes and also the immunophenotype of inflammatory cells in a diffuse type (panel A) and perivascular type (B) of tissue response. The amounts of the different elements in the periprosthetic tissues, analyzed by using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICPMS), are shown in panel C. Whiskers show standard error of the mean.

Figure 2.

Histological slides retrieved from a patient without periarticular cystic cavities (ballooning osteolysis). Perivascular infiltration by lymphocytes can be seen.

Figure 3.

Example of calcium detection using von Kossa staining (with black showing calcium).

Elemental analysis using ICPMS showed overall elevated levels of cobalt, chrome, titanium, iron, calcium, nickel, and molybdenum in patients with periprosthetic cysts compared to patients without ballooning osteolysis, but the differences were significant only for calcium and iron. No cadmium was detected in periprosthetic tissue (Figure 1C). Post-hoc analysis showed a highly significant difference in iron (p = 0.001) and calcium (p < 0.001) levels in osteolytic tissues compared to non-osteolytic tissues. The odds of having ballooning osteolysis was 297 times higher in patients with calcium levels >0.5 mg/g in periprosthetic tissue than in patients with calcium levels ≤0.5 mg/g (95% CI: 32–2,798; p < 0.001). Histomorphometric correlation and von Kossa staining showed that these calcium deposits had no bony architecture.

Discussion

Mechanisms of aseptic loosening described for hip and knee joints may not be directly extrapolated to the context of failed total ankle arthroplasty, considering the different biomechanical factors that prevail due to the small contact area between the tibia and the talus (Vickerstaff et al. 2007). Most studies in this context have been of a descriptive nature and the literature is patchy regarding the pathomechanism of ballooning osteolysis in TAA.

Histologically, samples from patients with ballooning osteolysis mostly showed necrotic and acellular areas, which is in accordance with the results of Koivu et al. (2009), who investigated 130 TAAs. These authors also found an increased number of histiocytes containing small, sharp particles of foreign material, which they interpreted as being a foreign-body reaction. This contrasts with a study by Dalat et al. (2013), who also found cysts with acellular eosinophilic necrosis inside, but free of foreign bodies. At the periphery of these areas, they found a macrophagic inflammatory reaction with a predominance of histiocytes. These authors could not detect any polynuclear infiltrates in the synovial sheath. In bone tissue, they found signs of resorption with macrophagic granulomatous reaction in the medullary tissue, compromising polynucleate giant cells and histiocytes. In our study, immunohistochemistry demonstrated that osteolytic tissues showed a higher expression of lymphocytes, and CD3-, CD11c-, CD20-, and CD68-positive cells in a diffuse pattern compared to non-osteolytic tissues. This might reflect a higher overall level of activity of inflammatory cells in periprosthetic tissues of patients with ballooning osteolysis contributing to disintegration of the tissue. Interestingly, we found elevated expression of markers for both types of tissue responses in patients with ballooning osteolysis—for the lymphocyte-dominated tissue reaction as well as for the macrophage-dominated tissue response. Furthermore, we observed that patients without ballooning osteolysis showed more clusters of inflammatory cells in a perivascular distribution, whereas patients with ballooning osteolysis were more characterized by a lymphocyte-dominated type of tissue response in a diffuse pattern. Within the perivascular distribution, differences in overall lymphocyte count, CD3 count, and CD20 count were most marked. This finding should be studied further, as the role of immunomodulation is currently mostly based on histological descriptions. Keeping these observations in mind, a theory of shift from a localized perivascular immunomodulation to a diffuse type of tissue response may be put forward. An inter-individual threshold appears likely, leading to a difference in tissue response and interfering with antigen-presenting pathways.

As a second part of our study, we performed elemental analysis from periprosthetic tissue in failed TAA. Kobayashi et al. (2004) found that the concentration of wear particles in synovial fluid taken from TAA was similar to that in those taken from total knee arthroplasties. Koivu et al. (2009) investigated metal content quantitatively in periprosthetic tissue of TAAs and found measurable values of chrome, cobalt, aluminium, and molybdenum in the samples of titanium-HA-coated Ankle Evolutive System TAAs. The authors found values of 230 μg per g of dry tissue for titanium—and for chrome, 18 μg, cobalt, 11 μg, aluminium, 1.7 μg, and molybdenum, 1.2 μg per g of dry tissue, respectively. Compared to our results, they found more titanium, but our samples showed higher values for chrome, cobalt, and molybdenum. However, the overall amount of metal detected was relatively low, and similar in osteolytic and non-osteolytic tissues. Thus, these metal particles might not fully explain ballooning osteolysis. It is important to note that we detected extremely high calcium values in samples from patients with osteolytic lesions relative to values in non-osteolytic tissues; calcium values >0.5 mg/g were highly associated with the presence of periprosthetic cysts. Van Kossa staining was also performed to quantify and “map” calcium deposits. In order to exclude high calcium values from bone or heterotopic ossification, we performed 2 sets of staining, von Kossa and hematoxylin-eosin, and directly compared each corresponding slide—which showed that these calcium deposits had no bony architecture.

In arthroplasty, hydroxyapatite (Ca5(PO4)3(OH)) was introduced as a coating to combine high material strength with the good bioactivity of the calcium phosphate compound. A recent survivorship analysis by Barg et al. (2013) identified implant generation as being an independent risk factor. Their investigation of 684 patients with 722 ankle replacements and a mean follow-up of 6 years showed that the odds of loosening was 15 times higher for implants with single hydroxyapatite coating compared to double-coated designs (p < 0.001). Collectively, our findings suggest that the hydroxyapatite coating of the implant may play a role in ballooning osteolysis seen in failed TAA. However, we observed 4 patients with ballooning osteolysis but low calcium values, and there was 1 patient with no ballooning osteolysis but high calcium values.

Most radiographic analyses describing periprosthetic cysts in failed TAA use a classification system described by Besse et al. (2009). To our knowledge, there is no generally accepted classification system for periprosthetic cysts in TAA based on CT scans. Differing definitions and classification systems have been described in this context (Hanna et al. 2007, Rodriguez et al. 2010, Kohonen et al. 2013, Yoon et al. 2013, Lucas y Hernandez et al. 2014). We used a definition proposed by Puri et al. (2002). Although periprosthetic cysts are most often diagnosed from plain radiographs, CT scans are superior for early detection of—and more accurate in quantification of—ballooning osteolysis (Easley et al. 2002, Hanna et al. 2007, Viste et al. 2015). CT also allows more accurate preoperative planning before revision surgery, especially regarding residual bone stock.

We acknowledge that our study had limitations, as different implant designs were included. Furthermore, not all patients had CT scans, because of logistic constraints. However, in the patients with no CT scans, conventional weight-bearing radiographs were not suggestive of periprosthetic ballooning osteolysis.

In summary, our combined data suggest that the hydroxyapatite coating of the implant may have a role in ballooning osteolysis seen in failed TAA.

The research leading to these results received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 602398. We thank Mr M. Schütze for technical support in elemental analysis, Mrs A. Schröder for help with histological staining, and Dr L. Choritz of the Department of Ophthalmology for allocation of and help with a Keyence microscope.

GS: study design, data evaluation and analysis, experimental work, statistical analysis, and manuscript preparation and editing. TR: data collection and evaluation, and experimental work. RH: data collection and evaluation, experimental work, and manuscript preparation. FA: statistical analysis, data analysis, and proofreading of manuscript. KS, BF, AR: data collection and evaluation. CL: supervision of work done, analysis of data, and manuscript preparation and editing.

Table.

De mographic and clinical data on patients

| Study cohort – failed TAA |

Controls | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No cysts | Cysts | Primary TAA | |

| n = 40 | n = 31 | n = 5 | |

| Age in yearsa | 57 (13) | 59 (12) | 62 (12) |

| Sex: F/M | 20/20 | 11/20 | 4/1 |

| SALTO, n | 16 | 21 | N/A |

| STAR, n | 18 | 7 | N/A |

| HINTEGRA, n | 3 | 2 | N/A |

| TARIC, n | 1 | 1 | N/A |

| Other, n | 2 | 0 | N/A |

| Implantation time in monthsa | 47 (34) | 74 (33) | N/A |

mean (SD)

References

- Barg A, Zwicky L, Knupp M, Henninger H B, Hintermann B.. HINTEGRA Total Ankle replacement: survivorship analysis in 684 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95 (13): 1175–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besse J-L, Brito N, Lienhart C.. Clinical evaluation and radiographic assessment of bone lysis of the AES total ankle replacement. Foot Ankle Int 2009; 30 (10): 964–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnin M, Judet T, Colombier J A, Buscayret F, Graveleau N, Piriou P.. Midterm results of the Salto Total Ankle Prosthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (424): 6–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnin M, Gaudot F, Laurent J-R, Ellis S, Colombier J-A, Judet T.. The Salto total ankle arthroplasty: survivorship and analysis of failures at 7 to 11 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469 (1): 225–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buechel F F, Pappas M J. (2004): Twenty-year evaluation of cementless mobile-bearing total ankle replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (424): 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalat F, Barnoud R, Fessy M H, Besse J L.. Histologic study of periprosthetic osteolytic lesions after AES total ankle replacement. A 22 case series. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2013; 99(6 Suppl): 285–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doets H C, Brand R, Nelissen R G H H.. Total ankle arthroplasty in inflammatory joint disease with use of two mobile-bearing designs. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88 (6): 1272–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easley M E, Vertullo C J, Urban W C, Nunley J A. (2002): Total ankle arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2002; 10 (3):157–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna R S, Haddad S L, Lazarus M L.. Evaluation of periprosthetic lucency after total ankle arthroplasty: helical CT versus conventional radiography. Foot Ankle Int 2007; 28 (8): 921–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintermann B, Valderrabano V, Dereymaeker G, Dick W.. The HINTEGRA ankle: rationale and short-term results of 122 consecutive ankles. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (424): 57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J J, Hallab N J, Urban R M, Wimmer M A.. Wear particles. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88Suppl2: 99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht S I, Estin M, Callaghan J J, Zimmerman M B, Alliman K J, Alvine F G, Saltzman C L.. The Agility total ankle arthroplasty. Seven to sixteen-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004; 86 (6): 1161–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A, Minoda Y, Kadoya Y, Ohashi H, Takaoka K, Saltzman C L.. Ankle arthroplasties generate wear particles similar to knee arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (424): 69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofoed H. Scandinavian Total Ankle Replacement (STAR). Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (424): 73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohonen I, Koivu H, Pudas T, Tiusanen H, Vahlberg T, Mattila K.. Does computed tomography add information on radiographic analysis in detecting periprosthetic osteolysis after total ankle arthroplasty? Foot Ankle Int 2013; 34 (2): 180–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivu H, Kohonen I, Sipola E, Alanen K, Vahlberg T, Tiusanen H.. Severe periprosthetic osteolytic lesions after the Ankle Evolutive System total ankle replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009; 91 (7): 907–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labek G, Klaus H, Schlichtherle R, Williams A, Agreiter M.. Revision rates after total ankle arthroplasty in sample-based clinical studies and national registries. Foot Ankle Int 2011; 32 (8): 740–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas y Hernandez J, Laffenêtre O, Toullec E, Darcel V, Chauveaux D.. AKILE™ total ankle arthroplasty: Clinical and CT scan analysis of periprosthetic cysts. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2014; 100 (8): 907–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri L, Wixson R L, Stern S H, Kohli J, Hendrix R W, Stulberg S D.. Use of helical computed tomography for the assessment of acetabular osteolysis after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002; 84 (4): 609–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez D, Bevernage B D, Maldague P, Deleu P A, Tribak K, Leemrijse T.. Medium term follow-up of the AES ankle prosthesis: High rate of asymptomatic osteolysis. Foot Ankle Surg 2010; 16 (2): 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valderrabano V, Hintermann B, Dick W.. Scandinavian total ankle replacement: a 3.7-year average followup of 65 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (424): 47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickerstaff J A, Miles A W, Cunningham J L.. A brief history of total ankle replacement and a review of the current status. Med Eng Phys 2007; 29 (10): 1056–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viste A, Al Zahrani N, Brito N, Lienhart C, Fessy M H, Besse J L.. Periprosthetic osteolysis after AES total ankle replacement: Conventional radiography versus CT-scan. Foot Ankle Surg 2015; 21(3):164–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Wijngaarden R, von der Plaat L, Nieuwe W R A, Doets H C, Westerga J, Haverkamp D.. Etiopathogenesis of osteolytic cysts ssociated with total ankle arthroplasty, a histological study. Foot Ankle Surg 2015; 21(2): 132–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert H G, Buchhorn G H, Fayyazi A, Flury R, Windler M, Köster G, Lohmann C H.. Metal-on-metal bearings and hypersensitivity in patients with artificial hip joints. A clinical and histomorphological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87 (1): 28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood P L R, Prem H, Sutton C.. Total ankle replacement: medium-term results in 200 Scandinavian total ankle replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90 (5): 605–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H S, Lee J, Choi W J, Lee J W.. Periprosthetic osteolysis after total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int 2013; 35 (1): 14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]