Abstract

Purpose

The increasing incidence of endometrial cancer (EC), in younger age at diagnosis, calls for new tissue-sparing treatment options. This work aims to evaluate the potential of imiquimod (IQ) in the treatment of low-grade EC.

Methods

Effects of IQ on the viabilities of Ishikawa and HEC-1A cells were evaluated using MTT assay. The ability of IQ to induce apoptosis was evaluated by testing changes in caspase 3/7 levels and expression of cleaved caspase-3, using luminescence assay and western blot. Apoptosis was confirmed by flow cytometry and the expression of cleaved PARP. Western blot was used to evaluate the effect of IQ on expression levels of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and BAX. Finally, the in vivo efficacy of IQ was tested in an EC mouse model.

Results

There was a decrease in EC cell viability following IQ treatment as well as increased caspase 3/7 activities, cleaved caspase-3 expression, and Annexin-V/ 7AAD positive cell population. Western blot results showed the ability of IQ in cleaving PARP, decreasing Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expressions, but not affecting BAX expression. In vivo study demonstrated IQ’s ability to inhibit EC tumor growth and progression without significant toxicity.

Conclusions

IQ induces apoptosis in low-grade EC cells in vitro, probably through its direct effect on Bcl-2 family protein expression. In, vivo, IQ attenuates EC tumor growth and progression, without an obvious toxicity. Our study provides the first building block for the potential role of IQ in the non-surgical management of low-grades EC and encouraging further investigations.

Keywords: endometrial cancer, imiquimod, apoptosis, Bcl-2, cleaved PARP

INTRODUCTION

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common gynecological malignancy in developed countries (1, 2). Obesity is identified as a major predisposition factor for EC with a rise in EC prevalence correlating with an increase in obesity rate (3). It is further a known risk factor with obese women having a 2–5 fold higher incidence of EC (3). For 2016, the American Cancer Society estimated that about 60,000 new cases of uterine cancers will be diagnosed and 10,470 deaths will occur (4, 5). Based on etiology and histology, EC can be categorized into two subtypes. Type I endometrial cancer (endometrioid EC), is induced by an uncontrolled, increased exposure to estrogen (E2) over a prolonged period of time. EC is often preceded by lesions know as endometrial hyperplasia (EH) (2, 6–8). Originally, Type I EC was considered as a disorder predominantly affecting postmenopausal women. However, more cases are now diagnosed in younger women and often are associated with obesity (9, 10). Type I EC is usually well or moderately differentiated and has a good prognosis. Type II (serous EC), on the other hand, is E2 independent, more common in postmenopausal women, poorly differentiated, more aggressive, and carries an unfavorable prognosis (7, 8, 11, 12). Most common molecular alterations found in Type I disease are microsatellite instabilities and mutations in PTEN, K-ras, and β-catenin (13). On the other hand, mutations related to Type II include P53, HER-2 and the down regulation of E-cadherin (13).

High E2 levels in Type I disease lead to an abnormal increase in endometrial glands proliferation rate (14). The action of E2 on the endometrium is not limited to increasing glandular proliferation, but also includes the inhibition of apoptosis of endometrial cells (14–16). Different mechanisms are involved in E2’s anti-apoptotic effects. For example, E2 activate a number of cell survival pathways including Src/ERK, mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), and serine–threonine kinase Akt/PKB pathways (17–19). On the nuclear level, E2 increases the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma/leukemia-2 gene (Bcl-2), resulting in a disturbance of its balance with the cancer suppressor gene Bcl-2-associated X protein gene (BAX) (17, 18, 20). Higher expression levels of Bcl-2 are found in E2 driven tumors such as breast cancer, low-grade EC, as well as EH (21, 22). This indicates that Bcl-2 is possibly involved in preneoplastic and neoplastic events leading to EC (21).

Total abdominal hysterectomy is the standard therapy for EC. However, in a subset of patients with low-grade early stage disease such as women of reproductive age wishing to preserve their fertility or women who are poor surgical candidates, conservative management can be offered (23, 24). Although progesterone shows efficacy in the conservative management of Type I EC, 30–35 % of women with well-differentiated tumors fail to respond to therapy or recur with the exact mechanisms of resistance to therapy unknown (24–27). For this particular subset of patients additional treatment options are needed.

Imiquimod (IQ), a nucleoside analog of the imidazoquinoline family, was initially developed as an antiviral agent against Human Papilloma Virus for the treatment of genital and perianal warts (28, 29). Recently, IQ was found to also exhibit antitumor effects against different malignancies such as prostate and urothelial cell carcinoma (30, 31). Clinical trials further demonstrated that IQ is effective in the treatment of vulvar, cervical, and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasias (32–34). IQ exhibits antitumor activity presumably by inducing apoptosis through direct and indirect pathways (35). By binding to Toll-like receptors (TLR) 7 and 8, IQ can indirectly induce apoptosis through cytokine-mediated stimulation of the immune system (28, 36). Although the exact apoptotic effect of IQ is still unclear, recent studies demonstrated that IQ could induce apoptosis most probably through reducing levels of Bcl-2 or other members of the Bcl-2 family like Myeloid cell leukemia 1 (Mcl-1) (37, 38). Thus, in this work, we evaluated IQ’s anticancer effect by focusing on its apoptotic potential in human EC cells in vitro, and also studied IQ’s efficacy in vivo using an EC xenograft mouse model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Imiquimod was purchased from Invivogen (CA, USA). MTT 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide was purchased from Invitrogen (OR, USA). Annexin-V conjugated to allophycocyanin (APC), 7-Aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD), and Annexin Binding Buffer were purchased from Life Technologies (NY, USA). Immunoblotting detection was conducted using the following antibodies: Anti-beta actin (Sigma, A5541), Anti Caspase-3 (Cell Signaling, 9662S), Anti-PARP (Cell Signaling, 9542T), Anti-Bcl-2 (Cell Signaling, 2876S), Anti –Bcl-xL (Abcam, GR192701-3) and Anti-BAX (Abcam, GR151406-1).

Cell culture

Ishikawa cells (well-differentiated human endometrial adenocarcinoma cell) were generously provided by Dr. Bae-Jump, University of North Carolina. HEC-1-A cells (moderately differentiated human adenocarcinoma) were purchased from American Type Cell Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Ishikawa cells were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium Eagle (Sigma, MO, USA) supplied with 1% Non-Essential Amino Acids (NEAA), 5% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS),100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. HEC-1-A cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium (ATCC, Manassas, VA) supplied with 5% FBS, and 100-units/mL penicillin, 100μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were grown and routinely maintained at 37 °C in 10 cm2 culture dishes.

Animals

Six-to-eight-week old female Nu/Nu athymic mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Animals were housed at the Center for Comparative Medicine Animal Facility at the University of Utah. Animals were treated following approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocols and in strict adherence to their guidelines.

Cell viability assay

To determine the effect of IQ on cell viability, Ishikawa and HEC-1A cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well and incubated for 24 hours in 100 μL media/well. Serial dilutions of IQ (0–100 μg/mL) were added to cells. At predetermined time points, 20 μL of 2.5 mg/mL of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) in PBS was added to the cells and cell were further incubated at 37 °C. After 4 hours, MTT solutions were completely removed and 100 μL DMSO was added to solubilize formazan crystals. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using Spectramax 250 microplate reader (Molecular device, CA, USA) and percent viability was calculated.

Caspase levels measurements

The activation of Caspases 3/7 after IQ exposure was measured using Caspase 3/7 -Glo (Promega, WI, USA) following manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 103 cells/ well in an opaque-wall 96 well plate with a solid bottom. Cells were treated with IQ for 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours. Caspase 3/7 –Glo reagent was added to wells containing cells, the plate was shaken at 300 RPM for 30 seconds, and incubated at room temperature for 45 minutes. Luminescence was measured using Infinite® M1000 PRO, and analyzed using Tecan i-control 1.10.4.0 software.

Flow cytometry

Annexin-V assay

Ishikawa and HEC-1A cells were assayed for Annexin-V binding after 72 hours of exposure to IQ as described (39). At 72 hours, cells were harvested, suspended in 500 μl Annexin binding buffer, (ABB) and incubated with 5 μl/mL Annexin-APC (Annexin-V conjugated to allophycocyanin for 15 minutes. The incubated treated cells and controls were analyzed using the FACSCanto-II (BD-BioSciences) at the University of Utah Core Facility. APC was excited with 635 nm laser and detected at 660 nm.

7-AAD assay

Ishikawa and HEC-1A cells were exposed to IQ for 72 hours, then suspended in 500 μl ABB. Cells were then stained by adding 1 μL/mL of 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD), and incubated in ice for 45 minutes. Treated as well as control cells were analyzed using the FACSCanto-II (BD-BioSciences). 7-AAD was excited with a 488 nm laser and detected at 660 nm. Spectral compensation was set by using cells single stained with APC alone, 7-AAD alone, or no stain.

Western blot

HEC-1A or Ishikawa cells were plated in 10 cm2 culture dishes, and then treated with IQ for 24, 48, and 72 hours. Whole cell lysates were prepared using Radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), and protein was quantified using DC Protein Assay Kit (Bio-rad, CA, USA). Cell lysates of IQ treated, and control cells (20 μg/well) were loaded in 4–20% Mini-Protean TGX Gels (Bio-rad, CA, USA), underwent electrophoresis, and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Bio-rad, CA, USA). After blocking the membrane with 5% (w/v) skimmed milk prepared in Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20 (TBS-T), blots were incubated with primary antibodies prepared based on manufacturer’s recommendation overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were then washed and incubated with the suitable secondary antibody, horseradish peroxidase-coupled anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibody. Bands were visualized using Western Bright ECL Kit for 5000 cm2 Membrane and Blue Basic Autoradiography Film (Bioexpress, CA, USA).

In vivo evaluation of IQ in endometrial cancer xenograft mouse model

Tumor chunks originally generated from human endometrial cancer cell line (HEC-1A) were dissected to ≈ 3–4 mm3 and implanted subcutaneously into the lower right flank of 6–8 week old female nu/nu athymic mice. Two weeks after tumor implantation, animals were randomized into either vehicle (n=5) or IQ treated group (n=14). Peritumoral injection of 100 μL of (1 mg/mL) IQ or vehicle (sterile water for injection) was carried out three times a week for 21 days. Tumor volume was measured using the following formula: V=0.5 (L × W2), were (L) corresponds to the length and (W) to the width of the tumor. Animals were sacrificed twenty-four hours after the last injection, and tumors were trimmed, fixed in 10% formalin for 48 hours, and then dehydrated in 70% ethanol. Tissues were analyzed at the Associated Regional and University Pathologists (ARUP) at the University of Utah. Hematoxylin and Eosin stains (H&E) of representative tissue slides were evaluated using light microscopy at the Department of Pathology, University of Utah by two independent pathologists.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and plotting graphs were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc. San Diego, CA). All experiments are conducted in triplicate unless otherwise indicated. Results are expressed as mean ± SD, and P<0.05 was considered significant. Student t-test and One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test were applied to compare the different treatment groups and controls.

Results

IQ impairs the viability of EC cells

We monitored the effect of IQ on Ishikawa and HEC-1A cells viability at an IQ concentration range of (0–100 μg/mL) for 24, 48, and 72 hours. Results suggest that both cell lines are sensitive to IQ treatment, but differ in time to maximum response. Ishikawa cells exhibited a dose-dependent decrease in cell viability that was apparent at 24 hours post-treatment, while the decrease in HEC-1A cell viability was more pronounced at 48 hours post treatment (Figure 1, A and B). IC-50s at 24, 48, and 72 hours were 53.85 ± 3.6, 22.85 ± 3, and 15.98 ± 2.6 for Ishikawa cells and 96.49 ± 9, 56.48 ± 5, and 30.08 ± 3.4 for HEC-1A cells respectively. The effect of IQ on Ishikawa and HEC-1A cells was also confirmed using sulforhodamine B colorimetric assay (Figure S1) (40).

Figure 1.

IQ impairs viabilities of endometrial cancer cells. Dose-response curve showing (A) Ishikawa and (B) HEC-1A cell viability over 72-hour time-course of IQ treatment

An increase in Caspase-3/7 activity and cleaved caspase-3 expression in cells after IQ treatment

To test our hypothesis - IQ is capable of inducing apoptosis in low-grade endometrial cancer - caspase 3/7 activity was measured after treating cells with ≈ 2 folds the IC50 (25μg/mL for Ishikawa cells and 50 μg/mL HEC-1A cells) for 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours. Ishikawa cells showed an increase in caspase-3/7 activity within 12 hours of IQ treatment (Figure 2, A). HEC-1A cells, in contrast, showed an increase in caspase 3/7 at 48 hours of therapy and after a slight initial decrease during the first 24 hours of drug exposure (Figure 2, B). The delayed onset of caspase activity to IQ for cells is consistent with cell viability results.

Figure 2.

Change in caspase-3/7 activity and the expression of cleaved caspase-3 after cells post-IQ treatment. (A) Ishikawa cells show a rapid onset of caspase activity with maximum signal at 48–72 hours post treatment. (B) HEC-1A cells exhibit a delayed response with increasing activity at 48 hours post treatment. Results of IQ and control cells are normalized to cells number respective to each time point, and are plotted as relative values to control. (C) Western blots of whole caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-3 at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours in Ishikawa (left) and HEC-1A cells (right).

The activation of caspase-3 was also analyzed using western blot. Activated caspase-3, denoted by a higher expression of cleaved caspase-3, was found with IQ treated cells. Cleaved caspase-3 was detected at 48, and 72 hours in Ishikawa and HEC-1A cells after IQ treatment, respectively (Figure 2, C and D) and (Figure S2, A).

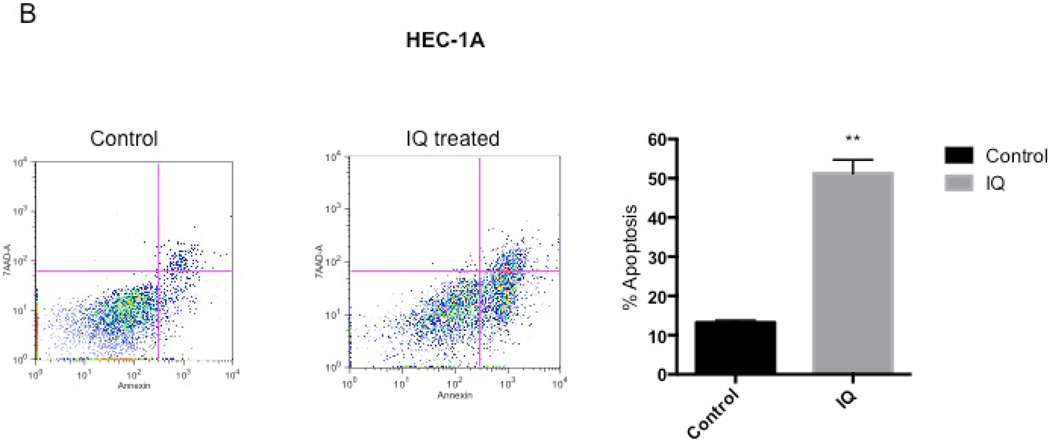

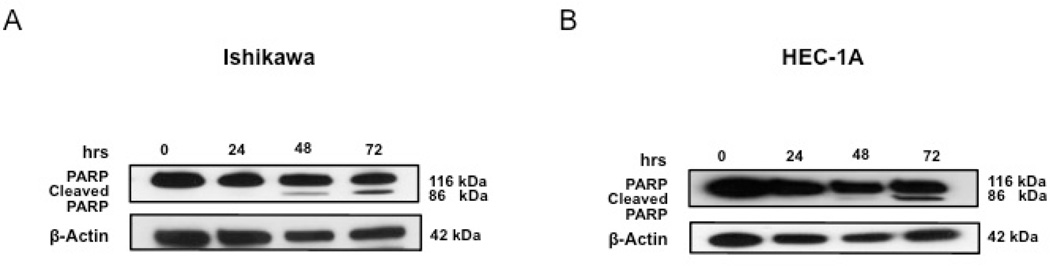

IQ boosts Annexin-V and 7-AAD positive cell numbers and induces PARP cleavage

To confirm the capability of IQ to induce apoptosis in EC cells, both flow cytometry (using 7-AAD and Annexin-V staining) and the expression of cleaved PARP were conducted. Figure 3, A and B showed that both Ishikawa and HEC-1A cells had an increase in 7-AAD and Annexin-V positive cell populations after IQ treatment compared to untreated cells. Consistent with these results, western blot analysis (Figure 4, A and B) and (Figure S2, B), depicted an increase in cleaved PARP expression in both cell lines after IQ treatment.

Figure 3.

IQ boosts Annexin-V and 7-AAD positive cell population. Representative flow cytometry charts showing Annexin-V and 7-AAD in control (left) and IQ treatment (middle) after 72 hours in (A) Ishikawa cells and (B) HEC-1A. Percent apoptosis was also quantified for each cell line as shown in bar graphs (left).

Figure 4.

IQ induces PARP cleavage in EC cells. Western blots showing IQ induced cleavage of PARP in Ishikawa (A) and HEC-1A cells (B).

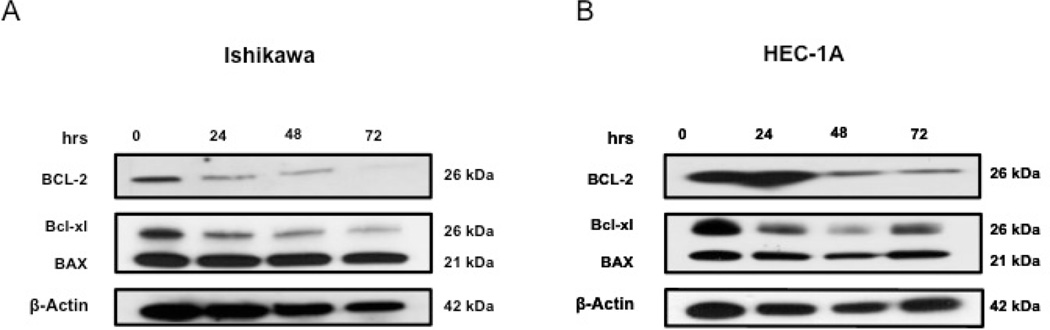

The expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in Ishikawa and HEC-1A cells are reduced by IQ

The effect of IQ on expression levels of the pro-survival proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-2 homologue B-cell lymphoma extra-large (Bcl-xL), and the pro-apoptotic protein BAX were evaluated using western blot. We detected a decrease in the expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL over time in both cell lines; however, BAX expression seemed to remain unaffected (Figure 5, A and B) and (Figure S2, C)

Figure 5.

IQ reduces the expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in Ishikawa and HEC-1A cells. Western blot analyses of both Ishikawa (A) and HEC-1A (B) showing Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and BAX expression levels after IQ treatment at different time points.

IQ attenuates tumor growth in endometrial cancer xenografts

A HEC-1A xenograft mouse model was utilized to evaluate the in vivo safety and efficacy of IQ in treating EC. We began IQ or vehicle administration two weeks after tumor implantation (average tumor volume of 50 mm3). Animals total body weights as well as tumor volumes were measured three times a week before, and throughout the course of therapy.

We observed that IQ prevented tumor growth and progression in vivo, in contrast to a continuous increase in mean tumors size in vehicle treated mice. The difference in mean tumor sizes before and after IQ therapy was not statistically significant. However, a significant difference present between tumors sizes before and after treatment in vehicle-treated group (Figure 6, A). Histopathological evaluation of excised tumors after IQ treatment showed extensive inflammatory infiltration composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes percolating among malignant cells. On the other hand, vehicle treated tumors demonstrating extensive tumor growth and no inflammatory infiltrate is recognized. (Figure 6, B). Animal weights through the course of therapy show no significant difference between IQ and vehicle-treated mice (Figure 6, C).

Figure 6.

IQ inhibits the growth of tumors in endometrial cancer xenografts. (A) Tumor size measurements for IQ and vehicle treated groups; tumor normalized to tumor size before treatment (left), representative excised tumors from vehicle and IQ treated tumors (right). (B) Histological evaluation revealed (top row) inflammatory infiltrate comprised of cells with neutrophils (top, left arrow) and lymphocytes appearance (bottom left arrow) percolating among malignant cells (right arrow) after IQ treatment (400X). While vehicle treated tumor (bottom row) shows sheets of malignant cells (20X) with morphology exhibiting marked nuclear pleomorphic, vesicular nuclei with variable prominent nucleoli (arrow) 400X. Numerous mitotic figures are noted, with no recognized inflammatory infiltrate among tumor cells. (C) Mice total body weight as measured during the course of therapy and normalized to mice weight prior to treatment.

Discussion

EC remains one of the most diagnosed gynecological cancer with 25% of cases occurring in women under the age of 40 (41). In addition to progesterone (P4) or progestins, gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and aromatase inhibitors are often used as means of conservative therapy and are suggested in recurrent cases or for cases refractory to progestins (42). Although initial reports were promising, GnRH only exhibited low response rates in cases with previous exposure to P4 (43). Also, the prolonged use of GnRH and aromatase inhibitors can lead to symptoms of menopause such as bone loss, osteoporosis, and endometrial atrophy (44). Based on its successful use in ovarian cancer, Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibition recently also found its way into the treatment of EC. This approach is based on PARP inhibitors exhibiting efficacy in cancers deficient in DNA repair genes, such as ovarian and breast (45, 46). It is known that up to 80% of endometrial cancers are associated with PTEN deficiency (13). PTEN deficient tumors exhibit the loss in Rad51, a key gene involved in the repair of DNA double-stranded breaks (47). Recently published findings report that PARP inhibitors were found less effective when higher levels of circulating E2 (hyperestrogenism) are present as found in many Type I EC patients (48). Therefore, it is imperative to identify new agents and targets capable of conservatively managing in lower grade EC.

In this study, we evaluated the potential of IQ in the management of low-grade endometrial cancer in vitro as well as in vivo. Our results indicate that IQ is capable of inducing apoptosis in low-grade EC cells. This induction is mostly due to the inhibitory effect of IQ on the expression of the Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL proteins. Importantly, IQ is also capable of inhibiting tumor progression in vivo in EC bearing mice.

Although both, Ishikawa and HEC-1A were sensitive to IQ, the delay in HEC-1A cell response to most IQ concentrations within the first 24 hours of treatment could be due to an initial inhibitory effect of IQ on cell proliferation (cytostasis). Two scenarios can possibly follow the inhibition of cell growth by an anticancer drug; cells could either recover and acquire resistance or suffer cytotoxicity (49). Cytotoxicity preceded by cytostasis was seen previously with some anticancer agents such as vincristine and paclitaxel (50, 51). The decrease in HEC-1A cell viability in a dose-dependent manner after longer incubation times (48 and 72 hours of treatment) suggests that cytotoxicity is eventually the end result in cells exposed to IQ. This data also suggests that well- and moderately- differentiated EC cells may respond differently to the same anti-cancer agent.

The goal for many anti-cancer agents is the induction of apoptosis by damaging DNA (49). In our results, IQ was able to affect caspase 3/7 activity, implicating IQ involvement in a mechanism that promotes apoptosis in EC. The direct increase in caspase 3/7 within 12 hours of Ishikawa cells exposed to IQ suggests that the agent is capable of inducing apoptosis in well-differentiated EC cells shortly after exposure. The initial lower caspase activity found in HEC-1A cells relative to control cells implies that cells were quiescent Therefore, cells were not able to proliferate before undergoing apoptosis as evidenced by an increase in caspase 3/7 within 48 hours of treatment (52). The significant increase in Annexin-V and 7-AAD positive cell populations identified by flow cytometric analyses, as well as cleavage of PARP, validate our findings that IQ harbors potential apoptosis inducing capabilities in EC.

To date the antitumor effect of IQ has been postulated to act mostly through a tumor-directed immune response, mediated via TLR 7 and 8 (28). However, our results document a direct, apoptotic effect of IQ independent of these receptors (30, 36, 53). With the lack of immune cells in vitro we hypothesize that apoptosis induced in EC cells is related to the IQ effect on the expression of Bcl-2 proteins. Increased Bcl-2 expression in the endometrium correlates with hormonal status showing an up-regulation by E2 (54–56). Histopathological analysis of 100 women with abnormal endometrial proliferation showed strongest Bcl-2 expressions in atypical EH and lower grades EC (57). These results suggest the involvement of Bcl-2 in the progression of EH and in early EC, identifying Bcl-2 as a potential target for treatment (21). Our data also suggest that IQ is capable of disturbing the Bcl-2/BAX ratio by altering Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expression in lower grade EC cells (Ishiakwa, and HEC-1A), revealing the possible activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway.

In vivo IQ is well tolerated, as there was a non-significant difference in body weight between IQ and vehicle-treated mice. While IQ was capable of preventing tumor growth in mice, treated tumors also exhibited leukocytic infiltration within the tumor milieu. Thus, the antitumor effect of IQ in vivo might involve additional mechanisms, including the stimulation of a tumor-directed immune response. Gynecological cancers including EC seem to be viable candidates for immunotherapy (58). Recently, studies demonstrated that adding an immunotherapeutic to EC treatment regimens can be advantageous (59). The administration of T cells stimulated by tumor lysate-pulsed autologous dendritic cells or a therapeutic cancer vaccine such as Wilms’ tumor Gene 1-loaded dendritic cells are capable of activating the patient’s own immune system by inducing a tumor-directed immune response (59, 60). Further, lymphocytic tumor infiltration indicates a more favorable prognosis in some EC patients (61). Hence, more detailed studies to further evaluate the exact role of IQ in initiating a tumor-directed immune response in EC are needed.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our results demonstrated that IQ attenuates the viability of well- and moderately- differentiated endometrial cancer cells, decrease the expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, activate caspase 3/7, cleaves PARP, and eventually induces apoptosis in vitro. In addition, local peritumoral administration of IQ is safe, well tolerated, and is capable of inhibiting tumor progression in an EC mouse xenograft model. Overall, our findings suggest that IQ holds promise in the treatment of lower grade endometrial cancers, encouraging further investigation to understand mechanisms of action in greater detail as well as to identify additional targets for conservative, non-surgical management of these malignancies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND DISCLOSURES

This research was supported in part by a Faculty and Creative Grant and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Utah, National Cancer Institute under award number R01-CA140348-01, and The Huntsman Cancer Institute’s Women’s Disease-Oriented Teams Research Funding. We would like to thank Dr. Victoria Bae-Jump, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for providing Ishikawa cells, Chieh-Hsiang Yang, Jesus Arellano, and Cameron Neilson for assisting with animal studies and data collection, and Benjamin J. Bruno, Dr. Andrew Dixon, and Dr. Sebastien Taurin for scientific discussions and help with data analyses.

ABBREVIATION

- BAX

Bcl-2-associated X protein gene

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma/leukemia-2 gen

- Bcl-xL

Bcl-2 homologue B-cell lymphoma-extra large

- E2

Estrogen

- EC

Endometrial cancer

- EH

Endometrial hyperplasia

- ER

Estrogen receptors

- GnRH

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone

- IQ

Imiquimod

- Mcl-1

Myeloid cell leukemia 1

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinas

- PARP

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

- P4

Progesterone

- TLR

Toll-like receptors

REFERENCES

- 1.Ho JC, Allen PK, Jhingran A, Westin SN, Lu KH, Eifel PJ, et al. Management of nodal recurrences of endometrial cancer with IMRT. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139(1):40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.07.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman AD, Ferguson SE, Atenafu EG, Kobel M, McAlpine JN, Panzarella T, et al. Canadian high risk endometrial cancer (CHREC) consortium: Analyzing the clinical behavior of high risk endometrial cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139(2):268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaaks R, Lukanova A, Kurzer MS. Obesity, endogenous hormones, and endometrial cancer risk: a synthetic review. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2002;11(12):1531–1543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felix AS, Scott McMeekin D, Mutch D, Walker JL, Creasman WT, Cohn DE, et al. Associations between etiologic factors and mortality after endometrial cancer diagnosis: The NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group 210 trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139(1):70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel L, Miller K, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2016;66(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuo K, Ramzan AA, Gualtieri MR, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Machida H, Moeini A, et al. Prediction of concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with endometrial hyperplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139(2):261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.07.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morice P, Leary A, Creutzberg C, Abu-Rustum N, Darai E. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amant F, Moerman P, Neven P, Timmerman D, Van Limbergen E, Vergote I. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2005;366(9484):491–505. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roett MA. Genital Cancers in Women: Uterine Cancer. FP Essent. 2015;438:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeves GK, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J, Spencer E, Bull D, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort study. BMJ. 2007;335(7630):1134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39367.495995.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murali R, Soslow RA, Weigelt B. Classification of endometrial carcinoma: more than two types. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(7):e268–e278. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70591-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahdi H, Elshaikh MA, DeBenardo R, Munkarah A, Isrow D, Singh S, et al. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy and pelvic radiation on pattern of recurrence and outcome in stage I non-invasive uterine papillary serous carcinoma. A multi-institution study. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(2):239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.01.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Llaurado M, Ruiz A, Majem B, Ertekin T, Colas E, Pedrola N, et al. Molecular bases of endometrial cancer: new roles for new actors in the diagnosis and the therapy of the disease. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;358(2):244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollard JW, Pacey J, Cheng SV, Jordan EG. Estrogens and cell death in murine uterine luminal epithelium. Cell Tissue Res. 1987;249(3):533–540. doi: 10.1007/BF00217324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JJ, Kurita T, Bulun SE. Progesterone action in endometrial cancer, endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and breast cancer. Endocr Rev. 2013;34(1):130–162. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song J, Rutherford T, Naftolin F, Brown S, Mor G. Hormonal regulation of apoptosis and the Fas and Fas ligand system in human endometrial cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8(5):447–455. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.5.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexaki VI, Charalampopoulos I, Kampa M, Nifli AP, Hatzoglou A, Gravanis A, et al. Activation of membrane estrogen receptors induce pro-survival kinases. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;98(2-3):97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reis FM, Petraglia F, Taylor RN. Endometriosis: hormone regulation and clinical consequences of chemotaxis and apoptosis. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(4):406–418. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amaral JD, Sola S, Steer CJ, Rodrigues CM. Role of nuclear steroid receptors in apoptosis. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(29):3886–3902. doi: 10.2174/092986709789178028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang R, He Y, Zhang X, Xing B, Sheng Y, Lu H, et al. Estrogen receptor-regulated microRNAs contribute to the BCL2/BAX imbalance in endometrial adenocarcinoma and precancerous lesions. Cancer Lett. 2012;314(2):155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bozdogan O, Atasoy P, Erekul S, Bozdogan N, Bayram M. Apoptosis-related proteins and steroid hormone receptors in normal, hyperplastic, and neoplastic endometrium. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2002;21(4):375–382. doi: 10.1097/00004347-200210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rein DT, Schondorf T, Breidenbach M, Janat MM, Weikelt A, Gohring UJ, et al. Lack of correlation between P53 expression, BCL-2 expression, apoptosis and ex vivo chemosensitivity in advanced human breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(6D):5069–5072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou R, Yang Y, Lu Q, Wang J, Miao Y, Wang S, et al. Prognostic factors of oncological and reproductive outcomes in fertility-sparing treatment of complex atypical hyperplasia and low-grade endometrial cancer using oral progestin in Chinese patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dorais J, Dodson M, Calvert J, Mize B, Travarelli JM, Jasperson K, et al. Fertility-sparing management of endometrial adenocarcinoma. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2011;66(7):443–451. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e31822f8f66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JJ, Chapman-Davis E. Role of progesterone in endometrial cancer. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28(1):81–90. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1242998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shao R. Progesterone receptor isoforms A and B: new insights into the mechanism of progesterone resistance for the treatment of endometrial carcinoma. Ecancermedicalscience. 2013;7:381. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2013.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erkanli S, Ayhan A. Fertility-sparing therapy in young women with endometrial cancer: 2010 update. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20(7):1170–1187. doi: 10.1111/igc.0b013e3181e94f5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schon MP, Schon M. Imiquimod: mode of action. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(Suppl 2):8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karnes JB, Usatine RP. Management of external genital warts. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(5):312–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith EB, Schwartz M, Kawamoto H, You X, Hwang D, Liu H, et al. Antitumor effects of imidazoquinolines in urothelial cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol. 2007;177(6):2347–2351. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han JH, Lee J, Jeon SJ, Choi ES, Cho SD, Kim BY, et al. In vitro and in vivo growth inhibition of prostate cancer by the small molecule imiquimod. Int J Oncol. 2013;42(6):2087–2093. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JM, Lee HJ, Kim SH, Kim HS, Ko HC, Kim BS, et al. Efficacy of 5% imiquimod cream on vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia in Korea: pilot study. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27(1):66–70. doi: 10.5021/ad.2015.27.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grimm C, Polterauer S, Natter C, Rahhal J, Hefler L, Tempfer CB, et al. Treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia with topical imiquimod: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2012;120(1):152–159. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31825bc6e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diakomanolis E, Haidopoulos D, Stefanidis K. Treatment of high-grade vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia with imiquimod cream. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(5):374. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200208013470521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schon MP, Schon M. Immune modulation and apoptosis induction: two sides of the antitumoral activity of imiquimod. Apoptosis. 2004;9(3):291–298. doi: 10.1023/b:appt.0000025805.55340.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sohn KC, Li ZJ, Choi DK, Zhang T, Lim JW, Chang IK, et al. Imiquimod induces apoptosis of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cells via regulation of A20. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schon M, Bong AB, Drewniok C, Herz J, Geilen CC, Reifenberger J, et al. Tumor-selective induction of apoptosis and the small-molecule immune response modifier imiquimod. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(15):1138–1149. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang SW, Chang CC, Lin CC, Tsai JJ, Chen YJ, Wu CY, et al. Mcl-1 determines the imiquimod-induced apoptosis but not imiquimod-induced autophagy in skin cancer cells. Journal of dermatological science. 2012;65(3):170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mossalam M, Matissek KJ, Okal A, Constance JE, Lim CS. Direct induction of apoptosis using an optimal mitochondrially targeted p53. Mol Pharm. 2012;9(5):1449–1458. doi: 10.1021/mp3000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Archibald M, Pritchard T, Nehoff H, Rosengren RJ, Greish K, Taurin S. A combination of sorafenib and nilotinib reduces the growth of castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016;11:179–200. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S97286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jayakrishnan K, Anupama R, Koshy A, Raju R. Endometrial carcinoma in a young subfertile woman with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2010;3(1):38–41. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.63122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kullander S. Treatment of endometrial cancer with GnRH analogs. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1992;124:69–73. doi: 10.1007/978-88-470-2186-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krasner C. Aromatase inhibitors in gynecologic cancers. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;106(1-5):76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gressel GM, Parkash V, Pal L. Management options and fertility-preserving therapy for premenopausal endometrial hyperplasia and early-stage endometrial cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131(3):234–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coleman RL, Sill MW, Bell-McGuinn K, Aghajanian C, Gray HJ, Tewari KS, et al. A phase II evaluation of the potent, highly selective PARP inhibitor veliparib in the treatment of persistent or recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer in patients who carry a germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation - An NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(3):386–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reinbolt RE, Hays JL. The Role of PARP Inhibitors in the Treatment of Gynecologic Malignancies. Front Oncol. 2013;3:237. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fraser M, Zhao H, Luoto KR, Lundin C, Coackley C, Chan N, et al. PTEN deletion in prostate cancer cells does not associate with loss of RAD51 function: implications for radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(4):1015–1027. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Janzen DM, Paik DY, Rosales MA, Yep B, Cheng D, Witte ON, et al. Low levels of circulating estrogen sensitize PTEN-null endometrial tumors to PARP inhibition in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12(12):2917–2928. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rixe O, Fojo T. Is cell death a critical end point for anticancer therapies or is cytostasis sufficient? Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(24):7280–7287. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meden H, Rath W, Kuhn W. [Taxol--a new cytostatic drug for therapy of ovarian and breast cancer] Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1994;54(4):187–193. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1023580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ulrichs K, Yu MY, Duncker D, Muller-Ruchholtz W. Immunosuppression by cytostatic drugs? Behring Inst Mitt. 1984;(74):239–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Theisen ER, Gajiwala S, Bearss J, Sorna V, Sharma S, Janat-Amsbury M. Reversible inhibition of lysine specific demethylase 1 is a novel anti-tumor strategy for poorly differentiated endometrial carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:752. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schon MP, Wienrich BG, Drewniok C, Bong AB, Eberle J, Geilen CC, et al. Death receptor-independent apoptosis in malignant melanoma induced by the small-molecule immune response modifier imiquimod. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122(5):1266–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Otsuki Y, Misaki O, Sugimoto O, Ito Y, Tsujimoto Y, Akao Y. Cyclic bcl-2 gene expression in human uterine endometrium during menstrual cycle. Lancet. 1994;344(8914):28–29. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhargava V, Kell DL, van de Rijn M, Warnke RA. Bcl-2 immunoreactivity in breast carcinoma correlates with hormone receptor positivity. Am J Pathol. 1994;145(3):535–540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McDonnell TJ, Troncoso P, Brisbay SM, Logothetis C, Chung LW, Hsieh JT, et al. Expression of the protooncogene bcl-2 in the prostate and its association with emergence of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1992;52(24):6940–6944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laban M, Ibrahim E, Agur W, Ahmed A. Bcl-2 may play a role in the progression of endometrial hyperplasia and early carcinogenesis, but not linked to further tumorigenesis. Journal of Microscopy and Ultrastructure. 2015;3(1):19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jmau.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kandalaft LE, Singh N, Liao JB, Facciabene A, Berek JS, Powell DJ, Jr, et al. The emergence of immunomodulation: combinatorial immunochemotherapy opportunities for the next decade. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116(2):222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coosemans A, Vanderstraeten A, Tuyaerts S, Verschuere T, Moerman P, Berneman ZN, et al. Wilms' Tumor Gene 1 (WT1)--loaded dendritic cell immunotherapy in patients with uterine tumors: a phase I/II clinical trial. Anticancer Res. 2013;33(12):5495–5500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Santin AD, Hermonat PL, Ravaggi A, Bellone S, Cowan C, Coke C, et al. Development and therapeutic effect of adoptively transferred T cells primed by tumor lysate-pulsed autologous dendritic cells in a patient with metastatic endometrial cancer. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2000;49(3):194–203. doi: 10.1159/000010246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jung IK, Kim SS, Suh DS, Kim KH, Lee CH, Yoon MS. Tumor-infiltration of T-lymphocytes is inversely correlated with clinicopathologic factors in endometrial adenocarcinoma. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2014;57(4):266–273. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2014.57.4.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.