Abstract

Atherosclerosis can be regarded as a chronic inflammatory state, in which macrophages play different and important roles. Phagocytic proinflammatory cells populate growing atherosclerotic lesions, where they actively participate in cholesterol accumulation. Moreover, macrophages promote formation of complicated and unstable plaques by maintaining proinflammatory microenvironment. At the same time, anti-inflammatory macrophages contribute to tissue repair and remodelling and plaque stabilization. Macrophages therefore represent attractive targets for development of antiatherosclerotic therapy, which can aim to reduce monocyte recruitment to the lesion site, inhibit proinflammatory macrophages, or stimulate anti-inflammatory responses and cholesterol efflux. More studies are needed, however, to create a comprehensive classification of different macrophage phenotypes and to define their roles in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. In this review, we provide an overview of the current knowledge on macrophage diversity, activation, and plasticity in atherosclerosis and describe macrophage-based cellular tests for evaluation of potential antiatherosclerotic substances.

1. Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease triggered by lipid retention in the arterial wall [1]. Certain areas of arteries, such as branching points and bends, are especially prone to atherosclerotic lesion development due to local disturbance of endothelial function. In such areas, circulating lipoprotein particles can penetrate into the arterial wall and accumulate in the subendothelial proteoglycan-rich layer of the arterial wall intima. According to current understanding, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), especially in its modified form, serves as a primary source of lipid accumulation in atherosclerotic lesions [2]. Atherogenic modification of LDL includes oxidation, enzymatic processing, desialylation, and aggregation. These modifications render the lipoprotein particles proinflammatory and induce an immune response leading to the formation of circulating LDL-containing immune complexes that are highly atherogenic [3]. Macrophages play a decisive role at all stages of atherosclerotic lesion progression [4, 5]. It is widely accepted that circulating monocyte-derived cells are recruited to the atherosclerotic lesion site (Figure 1), where they differentiate into macrophages. A number of recent studies, however, challenged this paradigm by demonstrating that most tissue macrophages develop independently of monocyte input from precursor cells present in adult tissues [6]. Interestingly, subendothelial intimal layer of human arterial wall contains a population of pluripotent pericyte-like cells that can differentiate into various cell types including phagocytes, positive for macrophage marker CD68 [7]. Macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions actively participate in lipoprotein ingestion and accumulation giving rise to foam cells filled with lipid droplets. Accumulation of foam cells contributes to lipid storage and atherosclerotic plaque growth. Macrophages populating the atherosclerotic plaque have a decreased ability to migrate, which leads to failure of inflammation resolution and to further progression of the lesion into complicated atherosclerotic plaque [8]. At this stage, macrophages contribute to the maintenance of the local inflammatory response by secreting proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and producing reactive oxygen species. Dying macrophages are responsible for necrotic core formation in progressing plaques [9]. The key role that macrophages play in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis makes them an attractive target for therapy development. Several possibilities have been considered, including inhibiting monocyte/macrophage recruitment to growing lesions, stimulating cholesterol efflux and diminishing lipid storage, and taking advantage of macrophage plasticity and the ability to polarize towards pro- or anti-inflammatory phenotypes [5].

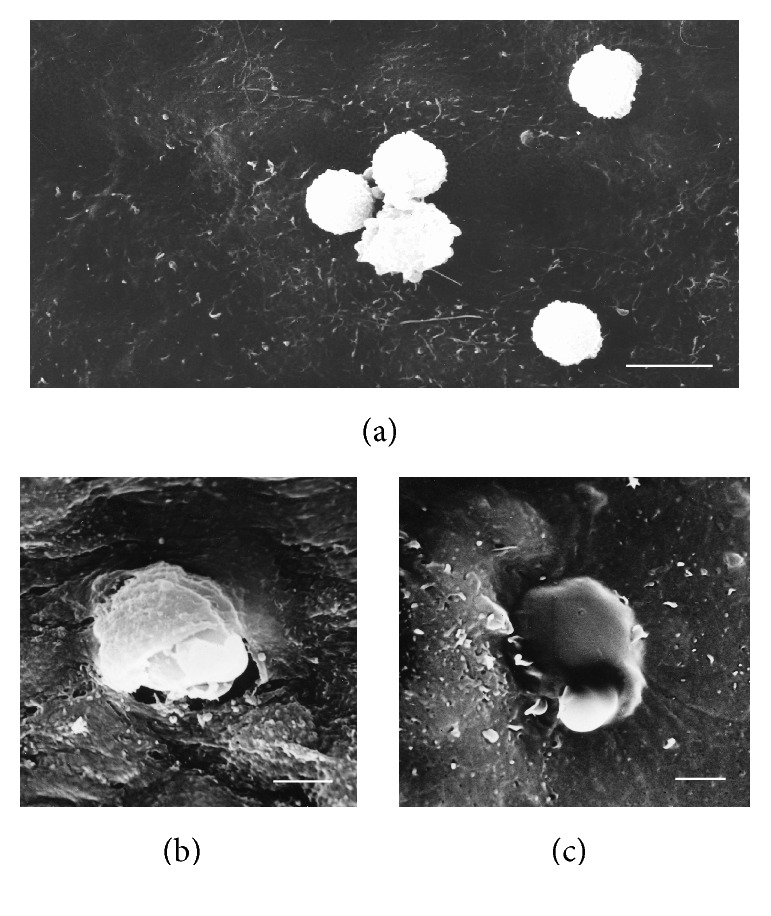

Figure 1.

Adhesion (a) and penetration (b, c) of blood monocytes into the intima of the human aorta. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Scale bars = 15 μm (a) and 5 μm (b, c).

2. Mononuclear Phagocyte System and the Role of Macrophages

According to the classical view, monocytes and macrophages form a continuous system, the mononuclear phagocyte system, which plays a central role in the innate immune response [10]. Circulating monocytes are recruited to the sites of injury or pathogen invasion by specific signals, including cytokines and chemokines released by tissue cells. At the lesion site, monocytes differentiate to macrophages that actively take part in the immune response by engulfing pathogens and damaged cells via phagocytosis and releasing proinflammatory factors. On the other hand, macrophages are also responsible for the resolution of the inflammatory response and tissue remodelling. The classical system regarded macrophages as terminally differentiated cells that are constantly renewed by monocytes newly recruited from circulation. This understanding was based primarily on tracing radiolabelled differentiating monocytes/macrophages in mice during inflammatory response. However, more recent studies have demonstrated that the ontogeny of tissue macrophages is more complex, and a large proportion of these cells derives from resident precursors [6].

Studying of monocyte/macrophage heterogeneity is challenging, because different subpopulations of these cells defined by expression of specific markers do not completely overlap in mice and humans. In both organisms, circulating monocytes can be divided into several distinct types based on the expression of surface molecules and chemokine receptors [11]. In humans, monocytes positive for CD14 and negative for CD16 surface antigens are the most prevalent and are referred to as classical monocytes [12, 13]. Like murine proinflammatory (LY6Chi) monocytes, these cells express CC-chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2). Monocytes positive for CD16 can be further divided into 2 subsets: CD14+CD16++ (nonclassical) and CD14++CD16+ (intermediate). Although both subclasses can produce proinflammatory factors, their functions in the organism are different. Nonclassical monocytes have antiviral activity and selectively produce proinflammatory factors in response to viral particles and nucleic acid-containing complexes, patrol the tissues, and are likely to be responsible for the local immune response [14]. Intermediate monocytes are capable of producing large amounts of proinflammatory molecules, such as tumor necrosis factor in response to stimulation [15]. Studying the distinct subpopulations of monocytes and their roles in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis may help in developing novel therapeutic approaches specifically targeting different stages of the disease progression.

It has been noted that the number of circulating proinflammatory monocytes is significantly increased in animal models of atherosclerosis, such as Apoe −/− mice in comparison to control animals [16]. Hypercholesterolaemia seems to promote the proliferation of haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and to enhance their sensitivity to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). On the contrary, production of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), which promotes cholesterol efflux and protects against atherosclerosis, reverses this phenotype [17].

During haematopoiesis, monocyte differentiation into macrophages is triggered mainly by two growth factors: GM-CSF and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-SCF) [18]. Differentiation of circulating monocytes can be induced by various stimuli, most importantly, in response to infection or aseptic inflammation. The latter process plays an important role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis [19]. Fatty streaks represent the early stages of atherosclerotic lesion development. It has been demonstrated that monocytes can be recruited to fatty streaks and can penetrate into the arterial wall due to the increased endothelial permeability linked to the local endothelial dysfunction. In mice, both proinflammatory and patrolling monocytes can be recruited to growing atherosclerotic lesions by P- and E-selectin-dependent rolling followed by intercellular adhesion molecule 1- (ICAM1-) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1- (VCAM1-) dependent adhesion [20]. Proinflammatory monocyte migration into the arterial wall is mediated by CCR2, CCR5, and CX3C-chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1) signalling. Correspondingly, inhibition of these molecules in Apoe −/− murine model of atherosclerosis prevented monocyte recruitment and atherosclerotic lesion growth [21]. Chemokines can be produced by activated endothelial cells at the lesion site, as well as by intimal macrophages and resident arterial wall cells. Proinflammatory monocytes penetrating into the arterial wall differentiate into macrophages and contribute to the inflammatory process and lesion development [16]. The role of patrolling monocytes in the disease pathogenesis is less clear. They participate in phagocytosis and might differentiate into dendritic cells [22].

Monocytes differentiating into macrophages demonstrate a number of morphological and structural changes, including enlargement, increase of organelles numbers, intensification of metabolism, enhanced expression of surface receptors, and altered sensitivity to signalling molecules. Differentiating monocytes have increased lysosomal enzyme activity, which prepares them for active phagocytosis and digestion of the engulfed material [23]. Importantly, macrophages that populate atherosclerotic lesions have a decreased ability to migrate. This contributes to the failure of inflammation resolution and to the formation of complicated plaques [5, 24]. In such plaques, different types of immune cells, as well as resident cells of the arterial wall, participate in the inflammatory process by secreting proinflammatory factors and matrix-degrading proteases. The increased cell death leads to the formation of necrotic core in the progressing plaque. On the other hand, recruitment of monocytes to the arterial wall can also be important for inflammation resolution and atherosclerotic lesion regression [25].

3. Macrophage Heterogeneity

One of the key features of macrophages is their high degree of plasticity that allows them to produce a fine-tuned response to various microenvironmental stimuli [26, 27]. Such plasticity and heterogeneity made it challenging to achieve a comprehensive macrophage classification. Moreover, in vitro studies of macrophage activation and differentiation may not reflect the in vivo situation accurately enough, since these processes are fine-tuned by various factors present in the organism's blood and tissues and can be modelled only roughly.

The identification of pro- and anti-inflammatory macrophages led to the establishment of the classical model of macrophage activation. This model defined two main phenotypes of macrophages: proinflammatory M1 and alternative M2. M1 macrophages differentiate in response to toll-like receptor (TLR) and interferon-γ signalling and can be induced by the presence of pathogen-associated molecular complexes (PAMPs), lipopolysaccharides, and lipoproteins. These cells secrete proinflammatory factors, such as tumor necrosis factor- (TNF-) α, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-12, and IL-23, and chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11. Proinflammatory macrophages produce high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) that also contribute to the development of the inflammatory response (Table 1) [28]. M2 macrophages that have anti-inflammatory properties are induced in response to Th2-type cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 and secrete anti-inflammatory factors, such as IL-1 receptor agonist and IL-10. Macrophages corresponding to M1 and M2 types were described in atherosclerotic lesions. Proinflammatory (M1) macrophages were enriched in progressing plaques, and M2 macrophages were present in regressing plaques, where they were involved in tissue repair and remodelling [28].

Table 1.

Macrophage phenotypes detected in humans and mice and their role in atherosclerosis (adapted with modifications from [26], with permission from Elsevier).

| Phenotype | Induction | Markers | Secreted molecules | Functions | Role in atherosclerosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 (human, mouse) | IFN-γ, TNF-α, LPS, and other TRL-mediated stimuli | IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, TNF-α, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 | IL-6, IL-10 (low), IL-12 (high), IL-23, TNF-α, iNOS, and ROS | Th1 response, antitumor | Plaque progression, maintaining inflammatory response |

| M2a (human, mouse) | IL-4, IL-13 | Human: MR, IL1RN Mouse: Arg-1, FIZZ1, and Ym1/2 |

IL-10, TGF-β, CCL17, and CCL22 | Tissue repair and remodelling | |

| M2b (human, mouse) | IL-1β, LPS | IL-10 (high), IL-12 (low) | IL-6, IL-10 (high), IL-12 (low), and TNF-α | Immune regulatory functions | Enriched in regressing plaques in humans and mice |

| M2c (human, mouse) | IL-10, TGF-β, and glucocorticoids | Human: MR Mouse: Arg-1 |

IL-10, TGF-β, and PTX3 | Phagocytosis, apoptotic cell clearance | |

| M2d (mouse) | TLR + A2R ligands | IL-12 (low), TNF-α (low) | IL-10, VEGF, and iNOS | Angiogenesis | Present in murine plaques |

| M4 (human) | CXCL4 | MR, MMP7, and S100A8 | IL-6, TNF-α, and MMP12 | Weak phagocytosis | Minimal foam cell formation, potentially proatherogenic |

| Mox | Oxidized LDL | HMOX-1, Nrf2, Srxn1, and Txnrd1 | IL-1β, IL-10 | Weak phagocytosis | Proatherogenic properties in mice |

| HA-mac (human) | Haemoglobin/ haptoglobin |

CD163 (high), HLA-DR (low) | HMOX-1 | Haemoglobin clearance | Atheroprotective |

| M (Hb) (human) | Haemoglobin/ haptoglobin |

MR, CD163 | ABCA1, ABCG1, and LXRα | Cholesterol efflux, atheroprotective | |

| Mhem (human, mouse) | Heme | ATF1, CD163 | LXRβ | Erythrocyte phagocytosis | Atheroprotective |

Recent studies have demonstrated that the bipolar M1/M2 classification does not accurately describe the macrophage diversity [26]. Therefore, additional classes of macrophages were distinguished depending on activation stimuli. Some authors proposed to divide the M2 type into several subgroups depending on the activation stimuli and protein expression pattern. M2a macrophages induced by IL-4 and IL-13 express high levels of CD206, IL-1 receptor agonist (IL1RN). M2b macrophages can be induced by TLR signalling and immune complexes, as well as IL-1R ligands [27]. They produce both anti-inflammatory (IL-10) and proinflammatory (IL-6, TNF-α) cytokines. M2c macrophages that can be induced by IL-10, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and glucocorticosteroids possess strong anti-inflammatory properties and produce pentraxin-3 (PTX3), TGF-β, and IL-10. They express Mer receptor kinase (MERTK) and are responsible for clearance of apoptotic cells [29]. M2d macrophages differentiated in response to TLR signalling through the adenosine A2A receptor were demonstrated to have angiogenic properties that can play a role in tumor progression and atherosclerotic plaque growth [30]. This classification, however, can be further broadened to include species-specific macrophage types. For instance, Mox macrophages were found only in mouse models of atherosclerosis, where they were induced by proatherogenic oxidized LDL. Furthermore, proinflammatory macrophages could be induced by platelet chemokine CXCL4 [31]. They lose the expression of the haemoglobin-haptoglobin scavenger receptor CD163, which is essential for haemoglobin clearance after the plaque haemorrhage and has therefore protective properties in atherosclerosis [32].

The described complexity of macrophage phenotypes urged the development of a more comprehensive classification system to avoid confusion and facilitate interpretation of data obtained in mice and humans. Joint efforts of several experts in the field resulted in formulation of guidelines for classification of macrophage phenotypes and polarization pathways [6, 26]. It was recommended to classify the different macrophage phenotypes based on the activation stimulus used and to avoid outdated terminology that could lead to confusion. It is currently unclear whether the results of in vitro experiments employing macrophage activation accurately reflect processes taking place in vivo, since macrophage activation may possibly be induced or modulated by macrophage isolation procedures. Moreover, the results obtained on experimental animals in many cases cannot be directly translated to humans, because the macrophage subtypes detected in different species (such as humans and mice) do not fully coincide. As macrophage activation is dependent on the expression of certain genes, studying changes of gene transcription in response to different stimuli will improve our understanding of this process. One of the important tools is the recently developed transcriptome analysis, which allows studying the complexity of macrophage activation variations [33]. A recent study has identified a network of transcriptional and epigenetic regulators that orchestrate the activation of proinflammatory macrophages [34]. The authors analyzed a variety of macrophage activation stimuli and proposed a model of human macrophage plasticity in inflammatory conditions defined by transcriptional regulation. Further study of the genetic mechanisms controlling macrophage activation may result in defining novel therapeutic targets for specific modulation of macrophage activation in pathological conditions.

4. The Role of Different Macrophage Types in Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerotic lesion site provides a specific microenvironment, enriched with activated cells, modified lipoproteins, and proinflammatory factors, as well as with dying and apoptotic cells. Correspondingly, the macrophage population of atherosclerotic plaques is heterogeneous [35]. The presence of relatively large numbers of proinflammatory macrophages (corresponding to M1 type) in atherosclerotic lesions is well known [28, 36]. However, alternatively activated macrophages have also been detected in the plaques [37]. Atherosclerotic plaque progression is associated with an increase of both macrophages populations, with cells expressing proinflammatory markers preferentially distributed in shoulder regions that are more susceptible to rupture and cells bearing markers of alternative activation located in the adventitia [38]. It has been demonstrated that anti-inflammatory, alternatively activated macrophages are present in more stable regions of plaques and are more resistant to foam cell formation [39]. Therefore, the pro- and anti-inflammatory macrophage subtypes may reflect the plaque progression/instability or regression correspondingly.

Identification of different types of macrophages in human tissues remains challenging because of the lack of specific and reliable markers. Immunohistochemical analysis of human aorta demonstrated the presence of proinflammatory macrophage marker TNF-α in atherosclerotic lesions as well as in grossly normal areas [40]. However, the quantity of TNF-α was increased in the lesion sites, which was also confirmed by quantitative PCR analysis of TNF-α expression. At the same time, atherosclerotic lesion areas also contained cells expressing CCL18, which are likely to be alternatively activated (M2-like) macrophages. More insight into macrophage polarization in proatherosclerotic conditions was gained by studying macrophage gene expression in vitro. Incubation of human monocyte-derived macrophages with multiply modified atherogenic LDL resulted in a significant increase of intracellular cholesterol accumulation associated with increased TNF-α and CCL18 expression [26].

Apart from the typical pro- and anti-inflammatory macrophages that can be classified into M1 and M2 types according to the old activation model, human atherosclerotic lesions contain specific macrophage phenotypes with pro- or antiatherogenic properties (Table 1). For instance, CD163-expressing macrophages could be found in haemorrhagic human plaques [41]. These cells are responsible for haemoglobin clearance and play a protective role in atherosclerotic lesions. Another atheroprotective macrophage subtype present in humans is Mhem. These cells also express CD163, as well as heme-dependent activating transcription factor 1 (ATF1), which induces expression of heme oxygenase 1 and liver X receptor- (LXR-) β. Mhem macrophages participate in haemoglobin clearance via erythrocyte phagocytosis and have increased cholesterol efflux due to expression of LXR-β-dependent genes LXR-α and ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 (ABCA1) [42]. These cells produce anti-inflammatory IL-10 and apolipoprotein E [43]. Recently described M4 macrophages can have proatherogenic properties and play a role in the formation of unstable plaques by producing MMP12 and promoting destabilization of the plaque fibrous cap [28].

5. Individual Difference in Macrophage Activation and Transcriptome Analysis

As mentioned above, human macrophages are characterized by great phenotypic diversity. Moreover, circulating monocytes can have unequal ability to polarize into different macrophage phenotypes, which can be relevant for atherosclerosis initiation and progression. It is important to evaluate susceptibility of circulating monocytes to pro- or anti-inflammatory polarization. For that purpose, monocytes were isolated from whole blood of healthy donors, apparently healthy subjects with predisposition to atherosclerosis, and patients with subclinical atherosclerosis evaluated by high-resolution ultrasonography of carotid arteries. Magnetic CD14-positive microbeads were used to obtain a pure monocyte population. Cells were stimulated with proinflammatory (IFN-γ) or anti-inflammatory (IL-4) factors [44]. In this simplified experimental model, the production of TNF-α and CCL18 was used as marker of pro- and anti-inflammatory activity, respectively, corresponding to M1 and M2 polarization of macrophages defined by the old paradigm. This approach revealed a remarkable individual difference in monocyte predisposition to activation [45]. This diversity did not, however, correlate with the presence or absence of subclinical atherosclerosis in the study subjects.

Transcriptome analysis is a powerful modern tool for studying monocyte/macrophage activation and function [23]. It provides a set of data on specific genes involved in different stages of macrophage activation. A detailed analysis of macrophage activation performed recently [33] explored changes in gene transcription induced by 28 different stimuli or their combinations. The study identified 49 sets of genes with similar transcriptional induction that become activated in macrophages in response to various stimuli and specific transcription factors that regulate them. More studies are needed, however, to reach an understanding of the complex mechanisms of macrophage activation in vivo [46]. It is likely that macrophage response to various stimuli in different individuals is largely influenced by genetic variation, especially in genomic regulatory elements that orchestrate the induced activation of macrophage genes. Such influence has recently been demonstrated, for instance, on F1 crosses of inbred mouse strains [47]. Memory of the past stimuli can also have a profound influence on monocyte ability for activation, as it has been demonstrated that some stimuli are not easily reversible and can influence the response of the immune system to subsequent stimulation [48].

A recent study has revealed an association of mitochondrial gene mutations with monocyte susceptibility to activation [49]. At least three heteroplasmic mutations of mtDNA, G14459A, A1555G, and G12315A, associated with atherosclerosis development in humans correlated with facilitated proinflammatory activation of circulating monocytes. Also, two homoplasmic mutations, A1811G and G9477A, tended to correlate with the degree of monocyte susceptibility to activation. On the other hand, G9477A mutation inversely correlated with the ability of monocytes to become activated. It is possible that mitochondrial dysfunction caused by mtDNA mutations activates autophagic clearance and contributed to the development of chronic inflammatory state, which also plays a role in the development of atherosclerosis. More studies are needed to evaluate the significance of mitochondrial genome for monocyte/macrophage system function.

6. Influence of Lipids on Macrophage Activation

LDL serves as the primary source of lipid accumulation in the arterial wall during atherosclerotic lesion development. In vitro studies have demonstrated that intracellular cholesterol accumulation is caused not by native but by atherogenic modified LDL. Unlike native LDL, modified LDL particles follow a different metabolic pathway, being internalized mostly through unregulated phagocytosis. Macrophages, with their well-developed phagocytic apparatus, are likely to play the key role in this process [28].

Both native and modified LDL were demonstrated to promote proinflammatory polarization of macrophages. A recent study on monocyte-derived macrophages has shown that incubation with LDL resulted in the increased expression of proinflammatory molecules TNF-α and IL-6 and decreased expression of CD206 and CD200R that are typical for anti-inflammatory (M2) macrophages [50]. Known forms of modified LDL also have a potent influence on macrophages promoting the formation of proinflammatory phenotype. Macrophages recognize modified LDL by means of TLRs and scavenger receptors. For instance, CD36, a scavenger receptor, can recognize oxidized LDL and associate with TLRs triggering proinflammatory signalling [51]. This favours macrophage polarization towards the proinflammatory phenotype. TLR activation is accompanied by the upregulation of protein kinases C and Syk, activation of NADPH oxidase 2 (gp91/Nox2), and increased ROS production [52]. As a result, macrophages increase the production of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 (CCL5). Moreover, oxidized LDL can induce inflammasome activation through CD36 signalling [53]. Exposure to oxidized LDL can also promote alternatively activated macrophages to shift their phenotype to a proinflammatory one through altered expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory genes [54].

It should be noted that the relationship between lipid accumulation and proinflammatory activation of macrophages is not straightforward. Lipidomic and transcriptomic study conducted in mice fed with normal or high cholesterol high fat diet demonstrated that macrophage-derived foam cells had a “deactivated” phenotype with reduced expression of proinflammatory factors [55]. Such anti-inflammatory response was attributed to cellular accumulation of desmosterol, one of the intermediates of cholesterol biosynthesis.

In mice, where a specific Mox type of macrophages has been described, oxidized phospholipids can induce both pro- and anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotypes to transform into Mox through activation of Nrf2, which promotes expression of a number of antioxidant genes [56]. Although Nrf2 signalling has some protective properties in atherosclerosis, its upregulation leads to inflammasome activation, which renders the Mox switch of macrophages proatherogenic [57]. Inflammasome activation in macrophages can result from phagocytosis of cholesterol crystals that can damage the lysosomal system [58]. Cholesteryl esters that are present in the plaque lipid core can stimulate macrophages and promote the inflammatory response and foam cell formation [52, 59]. The proinflammatory activity of different cholesteryl esters can be conveyed by different signalling pathways; for instance, 7-ketocholesteryl-9-carboxynonanoate was demonstrated to activate NF-κB pathway [60] and cholesteryl linoleate-MAP kinase signalling [61]. Another proinflammatory class of cholesterol derivatives present in atherosclerotic plaques is oxysterol. In macrophages, oxysterol can induce the expression of proinflammatory monocyte chemoattractant-1 (MCP-1) [62] and scavenger receptor CD36 [63]. CD36 expression is also stimulated by oxidized cholesterol esters [64]. This scavenger receptor has an important role in atherogenesis, as its downregulation through stimulation of αMβ2 integrins prevented the formation of proinflammatory macrophages and foam cells [65].

Phospholipase-mediated hydrolysis of lipoproteins resulting in the release of free phospholipids and fatty acids can occur in the acidic plaque microenvironment. These products greatly contribute to lipid accumulation in the arterial wall and plaque progression. It has been demonstrated that phospholipase A2-treated LDL increased the secretion of proinflammatory TNF-α and IL-6 by macrophages and stimulated foam cell formation [66]. The proinflammatory signalling of phospholipids and fatty acids is mediated by G-protein-coupled receptor G2A, which has an important role in the disease pathogenesis, as its deficiency results in advanced atherosclerosis and acquisition of proinflammatory M1 phenotype by macrophages [67]. Saturated fatty acids promote the proinflammatory phenotypic switch of macrophages through TLR-NF-κB signalling [68].

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) have well-known protective properties in atherosclerosis, which is partly explained by their anti-inflammatory effects on macrophages. Conjugated linoleic acid reduced the expression of proinflammatory genes such as NF-κB, CCL2, MMP9, phospholipase 2, and cyclooxygenase 2 in macrophages through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and inhibited atherosclerosis progression in mice. PUFA can also counteract the proatherosclerotic effects of saturated fatty acids, such as palmitate-induced expression of lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor 1 (LOX1) and fatty acid-binding protein [69]. Eicosapentaenoic acid and dihydroascorbic acid (DHA) have protective effects in atherosclerosis by alleviating proinflammatory activity and improving functions of macrophages [70]. Nitro-fatty acids (NFA) can be formed by interaction of reactive nitrogen species with fatty acids during oxidative stress [71]. It has been demonstrated that NFA possess anti-inflammatory and atheroprotective properties mediated by Nrf2 and PPARγ signalling [72]. Attenuation of atherosclerosis and plaque stabilization due to increased collagen deposition was observed in Apoe −/− mice treated with NFA [73].

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) has atheroprotective functions stimulating cholesterol efflux and catabolism [74]. Decreased relative levels of HDL versus LDL are observed in atherosclerotic patients. The protective effect of HDL is partly mediated by its anti-inflammatory activity: normalization of HDL serum levels in atherosclerotic mice led to a decrease of proinflammatory macrophage numbers in the lesions and to an increase of M2 macrophage markers CD163, Arg-1, and transcription factor FIZZ1 [75]. The expression of Arg-1 and FIZZ1 was dependent on STAT6 [76]. Another study has demonstrated that HDL inhibited the proinflammatory polarization of macrophages as assessed by such marker genes as TNF-α, IL-6, and CCL2, as well as surface markers, but did not stimulate the alternative activation of macrophages towards the anti-inflammatory phenotype [77]. Modulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory phenotypes of macrophages by lipids can be considered as a potential point of therapeutic intervention for treatment of atherosclerosis.

7. Foam Cell Formation

Intracellular accumulation of lipids is one of the early events in atherosclerosis development. Foam cell formation from macrophages is associated with downregulation of the expression of LDL receptor, which allows these cells to internalize apoB-containing lipoproteins. Modified LDL, which is internalized by alternative mechanisms, is the primary source of cholesterol accumulation in foam cells, as demonstrated by in vitro studies [78, 79]. Oxidation is the most studied atherogenic modification of LDL. It has been suggested that increased oxidative stress may account for the formation of atherogenic oxidized LDL and that the modified particle can trigger the development of the immune response and induce lipid accumulation in the arterial wall [80]. Studying of LDL composition of blood plasma of atherosclerotic patients revealed different types of LDL modification, including desialylation, glycation, acquisition of negative electric charge, and complex formation [81]. Complex formation renders modified LDL particles especially atherogenic. After penetration into the subendothelial layer of the arterial wall, modified LDL can associate with proteoglycan molecules, which increases its residence time and promotes lipid accumulation in the arterial wall cells. It is likely that a complex process of multiple LDL modification occurs in human bloodstream and in the arterial wall.

Modified LDL can be recognized by macrophages by means of scavenger receptors that play an important role in atherosclerosis development [82]. Scavenger receptors of macrophages include SR-A1, macrophage receptor with collagenous structure (MARCO, or SR-A2), CD36, SR-B1, LOX1, scavenger receptor expressed by endothelial cells 1 (SREC1), SR-PSOX, or CXCL16, recognizing phosphatidylserine and oxidized LDL [5]. In vitro studies have shown that degradation of modified (acetylated or oxidized) LDL by macrophages is mediated mostly by SR-A1 and CD36 [78]. Deficiency of these receptors partly inhibited foam cell formation in Apoe −/− mice, suggesting that other mechanisms of LDL uptake exist in macrophages [83]. Large quantities of native LDL that can be observed in hyperlipidemic conditions of growing plaques can also contribute to foam cell formation being internalized via pinocytosis [84].

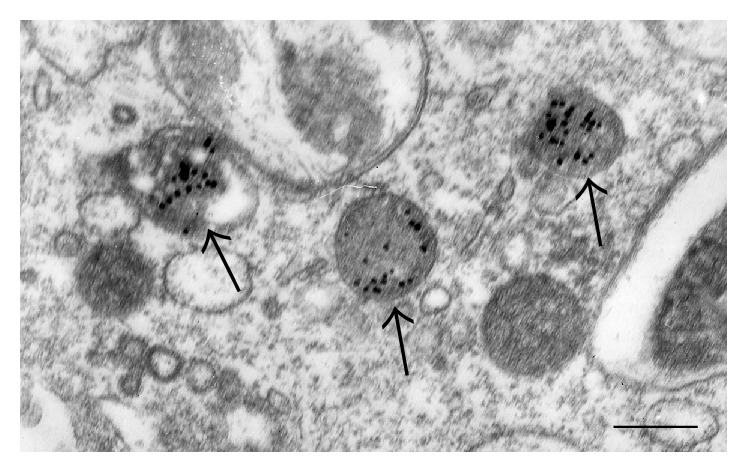

Ultrastructural analysis of macrophages incubated with modified LDL in vitro experiments showed the accumulation of LDL in the lysosomes (Figures 2 and 3). Biochemical studies revealed that, after internalization, LDL particles are degraded in the lysosomal compartments to free cholesterol and fatty acids, and free cholesterol is trafficked to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where it is reesterified by acetyl-coenzyme A:cholesterol acetyltransferase 1 (ACAT1) [85, 86]. Excessive cholesterol uptake has deleterious effects on cells. Cholesterol accumulation in the ER membranes leads to its defective esterification by ACAT1 and further increased storage. ER stress associated with cholesterol storage in macrophages also contributes to the disease progression increasing apoptosis in progressing plaques [87]. Increased cell death and impaired clearance of dying cells result in the formation of necrotic core in advanced atherosclerotic plaques. Cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains facilitate proinflammatory TLR- and NF-κB-mediated signalling [88].

Figure 2.

The presence of modified LDL, labelled with gold particles (arrows), in lysosomes of macrophages, visualized in an in vitro experiment. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). Scale bar = 600 nm.

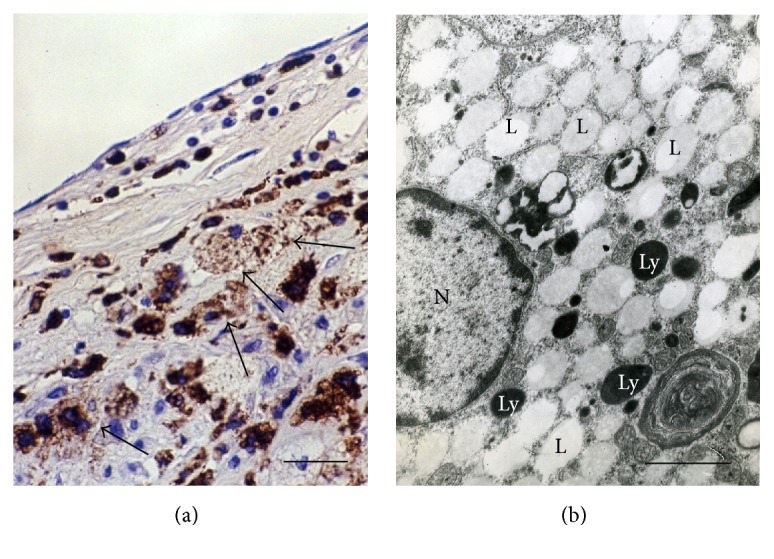

Figure 3.

Foam cells of macrophage origin in an atherosclerotic lesion of the human aorta (a, b). (a) CD68+ cells (brown), some of which display a typical foam cell appearance (arrows). Immunohistochemistry; peroxidase-anti-peroxidase (PAP) technique; counterstain with Mayer's hematoxylin. (b) A large number of lipid inclusions (“lipid droplets”) (L) that fill practically all the cytoplasm in a foam cell in a human atherosclerotic plaque. Ly: lysosome; N: nucleus. TEM. Scale bars = 100 μm (a) and 2 μm (b).

It should be noted that LDL circulating in the blood of healthy individuals usually does not cause accumulation of lipids in cultured macrophages, whereas LDL of atherosclerotic patients is in most cases a potent inducer of cellular lipidosis. Thus, LDL of atherosclerotic patients, unlike LDL of healthy individuals, is atherogenic. When added to primary culture of human monocyte-derived macrophages, atherogenic LDL isolated from the blood of atherosclerotic patients induces upregulation of proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α and anti-inflammatory chemokine CCL18 at the transcription level (Table 2). At the same time, nonatherogenic (native) LDL from healthy individuals had no effect on gene expression when added to cultured macrophages (Table 2). Therefore, multiply modified atherogenic LDL causes pro- and anti-inflammatory macrophage activation. This is a very important observation considering the significant role of the innate immunity and chronic inflammation in the occurrence and development of atherosclerotic lesions. The findings are in good agreement with the results of in situ studies that have demonstrated upregulation of the expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in atherosclerosis [35, 89].

Table 2.

Effect of LDL on cytokine gene expression.

| Native LDL | Atherogenic LDL | |

|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | 1.0 ± 0.3 (1.11) | 2.0 ± 0.5 (2.1) P = 0.05 |

| CCL18 | 1.1 ± 0.5 (1.0) | 4.4 ± 0.9 (2.8) P = 0.03 |

Monocytes were isolated from whole blood of healthy donors by density gradient followed by selection of CD14+ cells by magnetic separation. Cells were cultured for 7 days. Native or atherogenic LDL was added at a concentration of 100 µg/mL and the cells were incubated for 24 hours. RNA was isolated and gene expression was measured by RT-PCR technique. The table shows the relative expression of the genes. As 1, the control gene expression (without LDL) was taken. Values in parentheses are standard deviations.

To assess the impact of modified LDL-induced cholesterol accumulation on gene expression in macrophages, transcriptome study of macrophages incubated with oxidized, acetylated, and desialylated LDL was performed. Naturally, the addition of modified LDL caused changes in the activity of hundreds of macrophage genes. It is important to identify the genes that are associated with lipid accumulation. Incubation with modified LDL altered the activity of forty genes encoding molecules with known functions (Table 3). It should be noted that most of these genes (26 of 40) may be related to innate immunity function. This observation suggests that LDL-induced cholesterol accumulation in macrophages triggers an immune response. Further research should explain the link between the intracellular lipid accumulation and chronic inflammation in atherosclerotic lesions.

Table 3.

List of macrophage genes whose activity changes in the accumulation of intracellular cholesterol.

| Gene | Molecule | Functions |

|---|---|---|

| FCGBP | Fc fragment of IgG binding protein | Immune response |

| S100A8 | S100 calcium binding protein A8 | Immune response, migration, cell body formation |

| ITLN1 | Intelectin 1 (galactofuranose binding) | Pathogen metabolism |

| NCOR2 | Nuclear receptor corepressor 2 | Immune response |

| TPPP3 | Tubulin polymerization-promoting protein family member 3 | Cell body formation |

| AKR1C1 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C1 | Immune response |

| FAM65A | Family with sequence similarity 65, member A | Cell body formation |

| HECTD2 | HECT domain containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 | Metabolism |

| RD3 | Retinal degeneration 3 | Nerve features |

| TNFSF18 | Tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 18 | Immune response, migration |

| NEURL3 | Neuralized E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 3 | Metabolism |

| CD209 | CD209 molecule | Immune response, migration, dendritic cell features |

| STRIP2 | Striatin interacting protein 2 | Cell body formation |

| CCL4L2 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4-like 2 | Migration |

| TJP2 | Tight junction protein 2 | Migration |

| SPON2 | Spondin 2, extracellular matrix protein | Migration |

| L1CAM | L1 cell adhesion molecule | Migration |

| ARHGEF16 | Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 16 | Migration |

| NES | Nestin | Cell body formation, nerve features |

| F3 | Coagulation factor III (thromboplastin, tissue factor) | Migration |

| GALNT5 | Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 5 | Metabolism |

| MT1E | Metallothionein 1E | Metabolism |

| COQ2 | Coenzyme Q2 4-hydroxybenzoate polyprenyltransferase | Metabolism |

| TRIM54 | Tripartite motif containing 54 | Cell body formation |

| ANKRD63 | Ankyrin repeat domain 63 | Cell body formation |

| CCL24 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 24 | Immune response, migration |

| HIVEP3 | Human immunodeficiency virus type I enhancer binding protein 3 | Immune response |

| NETO2 | Neuropilin (NRP) and tolloid- (TLL-) like 2 | Nerve features |

| CCL4 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 | Immune response, migration |

| ACPP | Acid phosphatase, prostate | Metabolism |

| STARD4 | StAR-related lipid transfer (START) domain containing 4 | Metabolism |

| RANBP10 | RAN binding protein 10 | Cell body formation |

| ROBO2 | Roundabout guidance receptor 2 | Migration, nerve features |

| CHL1 | Cell adhesion molecule L1-like | Migration, nerve features |

| RARA | Retinoic acid receptor, alpha | Negative regulation of interferon-gamma production; positive regulation of interleukin-4 production, immune response |

| SLC16A9 | Solute carrier family 16, member 9 | Metabolism |

| HTR2A | 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 2A, G-protein-coupled | Nerve features |

| BCAR1 | Breast cancer antiestrogen resistance 1 | Migration |

| OR6K3 | Olfactory receptor, family 6, subfamily K, member 3 | Nerve features |

| CYP7B1 | Cytochrome P450, family 7, subfamily B, polypeptide 1 | Metabolism |

Increased lipid efflux could be a powerful therapeutic option for treatment of atherosclerosis. Several proteins facilitate lipid efflux in macrophages, including ABCA1 and ABCG1 [90]. ABCA1 and ABCG1 mediate lipid efflux to HDL particles and are upregulated in response to increased cellular cholesterol levels sensed by liver X receptors (LXRs). Their activation has also anti-inflammatory effects [91]. It was demonstrated that LXR activation in murine macrophages lacking ABCA1/G1 had a strong antiatherosclerotic effect, decreasing lesion area and complexity through reduction of inflammation [92]. The therapeutic option of activating LXRs for treatment of atherosclerosis is currently being explored. Another mechanism of cholesterol clearance from cells is lipophagy, which is a special type of autophagy [93]. Studies on atherosclerosis mouse model demonstrated the protective role of autophagy through regulation of inflammation [94] and cell death [95] in atherosclerotic plaques.

8. Macrophage-Based Tests for Diagnostics and Search of Antiatherosclerotic Substances

Given the crucial role that macrophages play in the parthenogenesis of atherosclerosis, it is important to establish reliable monocyte/macrophage-based models that can be used for studying molecular mechanisms of the disease pathogenesis as well as for screening of potential antiatherosclerotic substances. Recently, a monocyte/macrophage-based assay was developed to evaluate the changes in patient's monocyte response to pro- and anti-inflammatory stimuli, which would reveal the possible bias of the macrophages polarization towards M1 or M2 phenotype. A pure population of monocytes/macrophages was obtained using magnetic separation method [96]. Isolated cells were stimulated with proinflammatory LPS and IFN-γ or with anti-inflammatory IL-4 [97]. Macrophage polarization was assessed by measuring the production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines by ELISA. Proinflammatory activity of macrophages was assessed by the levels of secreted TNFα and IL-1β, and anti-inflammatory activity was assessed by the levels of CCL18 and IL-1Ra. Inflammasome activation can also be assessed in this system by measuring the IL-1β expression at mRNA level and comparing the results with the amount of mature IL-1β detected by ELISA or by measurement of active caspase-1, TNF-α, and IL-8 [98]. Characterization of macrophages can be performed by the analysis of a panel of markers, including MMR, CD163, TGF-RII, CSFR1, TNFRI, CD16, CD32, CD64, and stabilin-1, as well as expression of TLR1, TLR2, and TLR4 at mRNA level and on the cell surface.

Monocyte/macrophage-based method was used to analyze activation of monocytes isolated from blood of healthy subjects (n = 19), atherosclerosis patients (n = 22), and breast cancer patients (n = 18). It was demonstrated that the production of proinflammatory TNF-α was significantly lower in atherosclerotic patients and significantly higher in cancer patients in comparison to healthy subjects, whereas the production of anti-inflammatory CCL18 was decreased in both atherosclerosis and cancer patients [40]. Comparison of subjects with predisposition to atherosclerosis (n = 21, mean age 63 ± 9 years), subjects with subclinical atherosclerosis (n = 21, mean age 62 ± 7 years), and healthy subjects (n = 21, mean age 60 ± 9 years), as estimated by the age-adjusted carotid intima media thickness (CIMT) value, revealed the dramatic individual differences between the analyzed subjects that may reflect the individuals' predisposition to immunopathology [40]. Macrophages from subjects with subclinical atherosclerosis were characterized by especially low degree of polarization towards pro- and anti-inflammatory phenotypes.

Macrophage-based model could also be successfully used for evaluation of potential antiatherosclerotic substances. The ability of botanicals with known anti-inflammatory properties to modulate the activation of macrophages was evaluated using IFN-γ and IL-4 stimulation. Cultured human macrophages were incubated with extracts of hawthorn flowers (Crataegus sp.), elderberry (Sambucus nigra), calendula (Calendula officinalis), St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum), and violet (Viola sp.), and the levels of TNF-α and CCL18 were measured after 6 days. Extracts of hawthorn and St. John's wort significantly inhibited both TNF-α and CCL18 production indicative of macrophage depolarization [40]. This interesting immunomodulatory effect should be explored in more detail to reveal its possible therapeutic significance.

9. Conclusion

Macrophages play a central role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. They actively participate in LDL uptake and lipid accumulation in the arterial wall becoming foam cells. Macrophage population is heterogeneous and consists of several subtypes of cells that differ by their functions and gene expression profiles. Proinflammatory macrophages are implicated in plaque initiation and progression, while anti-inflammatory macrophages participate in plaque stabilization. Monocytes/macrophages isolated from the blood of healthy subjects and atherosclerotic patients can accumulate lipids upon incubation with atherogenic LDL and can be used to create cell-based models for evaluation of potential antiatherosclerotic substances. Interestingly, monocytes/macrophages isolated from blood demonstrated a significant interindividual variability, which could possibly be explained by varying gene regulation and previous history of immune cells activation. Given the importance and variety of macrophage functions in atherosclerosis, these cells are considered an attractive therapeutic target. Future studies should focus on further investigation of the roles of different types of macrophages in atherosclerosis progression and on development of macrophage-targeting therapies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Grant no. 14-15-00112).

Competing Interests

The authors report no competing interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Ross R. Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340(2):115–126. doi: 10.1056/nejm199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krauss R. M. Lipoprotein subfractions and cardiovascular disease risk. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2010;21(4):305–311. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32833b7756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tertov V. V., Orekhov A. N., Kacharava A. G., Sobenin I. A., Perova N. V., Smirnov V. N. Low density lipoprotein-containing circulating immune complexes and coronary atherosclerosis. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 1990;52(3):300–308. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(90)90071-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore K. J., Tabas I. Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell. 2011;145(3):341–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore K. J., Sheedy F. J., Fisher E. A. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2013;13(10):709–721. doi: 10.1038/nri3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ginhoux F., Jung S. Monocytes and macrophages: developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2014;14(6):392–404. doi: 10.1038/nri3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orekhov A. N., Bobryshev Y. V., Chistiakov D. A. The complexity of cell composition of the intima of large arteries: focus on pericyte-like cells. Cardiovascular Research. 2014;103(4):438–451. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Randolph G. J. Mechanisms that regulate macrophage burden in atherosclerosis. Circulation Research. 2014;114(11):1757–1771. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.114.301174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seimon T., Tabas I. Mechanisms and consequences of macrophage apoptosis in atherosclerosis. Journal of Lipid Research. 2009;50:S382–S387. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800032-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Furth R., Cohn Z. A. The origin and kinetics of mononuclear phagocytes. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1968;128(3):415–435. doi: 10.1084/jem.128.3.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geissmann F., Jung S., Littman D. R. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19(1):71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziegler-Heitbrock L. The CD14+ CD16+ blood monocytes: their role in infection and inflammation. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2007;81(3):584–592. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziegler-Heitbrock L., Ancuta P., Crowe S., et al. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood. 2010;116(16):e74–e80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cros J., Cagnard N., Woollard K., et al. Human CD14dim monocytes patrol and sense nucleic acids and viruses via TLR7 and TLR8 receptors. Immunity. 2010;33(3):375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belge K.-U., Dayyani F., Horelt A., et al. The proinflammatory CD14+CD16+DR++ monocytes are a major source of TNF. The Journal of Immunology. 2002;168(7):3536–3542. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swirski F. K., Libby P., Aikawa E., et al. Ly-6Chi monocytes dominate hypercholesterolemia-associated monocytosis and give rise to macrophages in atheromata. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117(1):195–205. doi: 10.1172/jci29950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yvan-Charvet L., Pagler T., Gautier E. L., et al. ATP-binding cassette transporters and HDL suppress hematopoietic stem cell proliferation. Science. 2010;328(5986):1689–1693. doi: 10.1126/science.1189731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicola N. A., Metcalf D. Ciba Foundation Symposium. Vol. 118. John Wiley & Sons; 1986. Specificity of action of colony-stimulating factors in the differentiation of granulocytes and macrophages; pp. 7–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woollard K. J., Geissmann F. Monocytes in atherosclerosis: subsets and functions. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2010;7(2):77–86. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galkina E., Ley K. Vascular adhesion molecules in atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2007;27(11):2292–2301. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.107.149179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Combadière C., Potteaux S., Rodero M., et al. Combined inhibition of CCL2, CX3CR1, and CCR5 abrogates Ly6Chi and Ly6Clo monocytosis and almost abolishes atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. Circulation. 2008;117(13):1649–1657. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.107.745091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swirski F. K., Weissleder R., Pittet M. J. Heterogeneous in vivo behavior of monocyte subsets in atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2009;29(10):1424–1432. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.108.180521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Novoselov V. V., Sazonova M. A., Ivanova E. A., Orekhov A. N. Study of the activated macrophage transcriptome. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2015;99(3):575–580. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Randolph G. J. Emigration of monocyte-derived cells to lymph nodes during resolution of inflammation and its failure in atherosclerosis. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2008;19(5):462–468. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32830d5f09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nathan C., Ding A. Nonresolving inflammation. Cell. 2010;140(6):871–882. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murray P., Allen J., Biswas S., et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41(1):14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez F. O., Sica A., Mantovani A., Locati M. Macrophage activation and polarization. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2008;13(2):453–461. doi: 10.2741/2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chistiakov D. A., Bobryshev Y. V., Nikiforov N. G., Elizova N. V., Sobenin I. A., Orekhov A. N. Macrophage phenotypic plasticity in atherosclerosis: the associated features and the peculiarities of the expression of inflammatory genes. International Journal of Cardiology. 2015;184(1):436–445. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zizzo G., Hilliard B. A., Monestier M., Cohen P. L. Efficient clearance of early apoptotic cells by human macrophages requires M2c polarization and MerTK induction. The Journal of Immunology. 2012;189(7):3508–3520. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrante C. J., Pinhal-Enfield G., Elson G., et al. The adenosine-dependent angiogenic switch of macrophages to an M2-like phenotype is independent of interleukin-4 receptor alpha (IL-4Rα) signaling. Inflammation. 2013;36(4):921–931. doi: 10.1007/s10753-013-9621-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gleissner C. A., Shaked I., Little K. M., Ley K. CXC chemokine ligand 4 induces a unique transcriptome in monocyte-derived macrophages. Journal of Immunology. 2010;184(9):4810–4818. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gleissner C. A. Macrophage phenotype modulation by CXCL4 in atherosclerosis. Frontiers in Physiology. 2012;3, article 1 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00001.Article 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xue J., Schmidt S. V., Sander J., et al. Transcriptome-based network analysis reveals a spectrum model of human macrophage activation. Immunity. 2014;40(2):274–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt S. V., Krebs W., Ulas T., et al. The transcriptional regulator network of human inflammatory macrophages is defined by open chromatin. Cell Research. 2016;26(2):151–170. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Paoli F., Staels B., Chinetti-Gbaguidi G. Macrophage phenotypes and their modulation in atherosclerosis. Circulation Journal. 2014;78(8):1775–1781. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-0621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cochain C., Zernecke A. Macrophages and immune cells in atherosclerosis: recent advances and novel concepts. Basic Research in Cardiology. 2015;110(4, article 34):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00395-015-0491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bouhlel M. A., Derudas B., Rigamonti E., et al. PPARγ activation primes human monocytes into alternative M2 macrophages with anti-inflammatory properties. Cell Metabolism. 2007;6(2):137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stöger J. L., Gijbels M. J. J., van der Velden S., et al. Distribution of macrophage polarization markers in human atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2012;225(2):461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chinetti-Gbaguidi G., Baron M., Bouhlel M. A., et al. Human atherosclerotic plaque alternative macrophages display low cholesterol handling but high phagocytosis because of distinct activities of the PPARγ and LXRα pathways. Circulation Research. 2011;108(8):985–995. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.110.233775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orekhov A. N., Sobenin I. A., Gavrilin M. A., et al. Macrophages in immunopathology of atherosclerosis: a target for diagnostics and therapy. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2015;21(9):1172–1179. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666141013120459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyle J. J., Harrington H. A., Piper E., et al. Coronary intraplaque hemorrhage evokes a novel atheroprotective macrophage phenotype. American Journal of Pathology. 2009;174(3):1097–1108. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boyle J. J., Johns M., Kampfer T., et al. Activating transcription factor 1 directs Mhem atheroprotective macrophages through coordinated iron handling and foam cell protection. Circulation Research. 2012;110(1):20–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boyle J. J. Heme and haemoglobin direct macrophage Mhem phenotype and counter foam cell formation in areas of intraplaque haemorrhage. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2012;23(5):453–461. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328356b145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gordon S., Martinez F. O. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity. 2010;32(5):593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Orekhov A. N., Nikiforov N. G., Elizova N. V., Ivanova E. A., Makeev V. J. Phenomenon of individual difference in human monocyte activation. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2015;99(1):151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Natoli G., Monticelli S. Macrophage activation: glancing into diversity. Immunity. 2014;40(2):175–177. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heinz S., Romanoski C. E., Benner C., et al. Effect of natural genetic variation on enhancer selection and function. Nature. 2013;503(7477):487–492. doi: 10.1038/nature12615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ostuni R., Piccolo V., Barozzi I., et al. Latent enhancers activated by stimulation in differentiated cells. Cell. 2013;152(1-2):157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Orekhov A. N., Zhelankin A. V., Kolmychkova K. I., et al. Susceptibility of monocytes to activation correlates with atherogenic mitochondrial DNA mutations. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2015;99(3):672–676. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Sharea A., Lee M. K. S., Moore X., et al. Native LDL promotes differentiation of human monocytes to macrophages with an inflammatory phenotype. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2016;115:762–772. doi: 10.1160/TH15-07-0571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stewart C. R., Stuart L. M., Wilkinson K., et al. CD36 ligands promote sterile inflammation through assembly of a Toll-like receptor 4 and 6 heterodimer. Nature Immunology. 2010;11(2):155–161. doi: 10.1038/ni.1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bae Y. S., Lee J. H., Choi S. H., et al. Macrophages generate reactive oxygen species in response to minimally oxidized low-density lipoprotein: toll-like receptor 4- and spleen tyrosine kinase-dependent activation of NADPH oxidase 2. Circulation Research. 2009;104(2):210–218. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.108.181040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang Y., Wang M., Huang K., et al. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces secretion of interleukin-1β by macrophages via reactive oxygen species-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2012;425(2):121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Tits L. J. H., Stienstra R., van Lent P. L., Netea M. G., Joosten L. A. B., Stalenhoef A. F. H. Oxidized LDL enhances pro-inflammatory responses of alternatively activated M2 macrophages: a crucial role for Krüppel-like factor 2. Atherosclerosis. 2011;214(2):345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spann N. J., Garmire L. X., McDonald J. G., et al. Regulated accumulation of desmosterol integrates macrophage lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Cell. 2012;151(1):138–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kadl A., Meher A. K., Sharma P. R., et al. Identification of a novel macrophage phenotype that develops in response to atherogenic phospholipids via Nrf2. Circulation Research. 2010;107(6):737–746. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.215715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Freigang S., Ampenberger F., Spohn G., et al. Nrf2 is essential for cholesterol crystal-induced inflammasome activation and exacerbation of atherosclerosis. European Journal of Immunology. 2011;41(7):2040–2051. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rajamaki K., Lappalainen J., Öörni K., et al. Cholesterol crystals activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages: a novel link between cholesterol metabolism and inflammation. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(7, article e11765) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harkewicz R., Hartvigsen K., Almazan F., Dennis E. A., Witztum J. L., Miller Y. I. Cholesteryl ester hydroperoxides are biologically active components of minimally oxidized low density lipoprotein. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(16):10241–10251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m709006200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang Z., Li W., Wang R., et al. 7-Ketocholesteryl-9-carboxynonanoate induced nuclear factor-kappa B activation in J774A.1 macrophages. Life Sciences. 2010;87(19–22):651–657. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huber J., Boechzelt H., Karten B., et al. Oxidized cholesteryl linoleates stimulate endothelial cells to bind monocytes via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathway. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2002;22(4):581–586. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000012782.59850.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leonarduzzi G., Gamba P., Sottero B., et al. Oxysterol-induced up-regulation of MCP-1 expression and synthesis in macrophage cells. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2005;39(9):1152–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leonarduzzi G., Gargiulo S., Gamba P., et al. Molecular signaling operated by a diet-compatible mixture of oxysterols in up-regulating CD36 receptor in CD68 positive cells. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research. 2010;54(1):S31–S41. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jedidi I., Couturier M., Thérond P., et al. Cholesteryl ester hydroperoxides increase macrophage CD36 gene expression via PPARα . Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;351(3):733–738. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yakubenko V. P., Bhattacharjee A., Pluskota E., Cathcart M. K. α m β 2 integrin activation prevents alternative activation of human and murine macrophages and impedes foam cell formation. Circulation Research. 2011;108(5):544–554. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.110.231803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boyanovsky B. B., Li X., Shridas P., Sunkara M., Morris A. J., Webb N. R. Bioactive products generated by group V sPLA2 hydrolysis of LDL activate macrophages to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines. Cytokine. 2010;50(1):50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bolick D. T., Skaflen M. D., Johnson L. E., et al. G2A deficiency in mice promotes macrophage activation and atherosclerosis. Circulation Research. 2009;104(3):318–327. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.181131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dasu M. R., Jialal I. Free fatty acids in the presence of high glucose amplify monocyte inflammation via Toll-like receptors. American Journal of Physiology—Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;300(1):E145–E154. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00490.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ishiyama J., Taguchi R., Yamamoto A., Murakami K. Palmitic acid enhances lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor (LOX-1) expression and promotes uptake of oxidized LDL in macrophage cells. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209(1):118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Merched A. J., Ko K., Gotlinger K. H., Serhan C. N., Chan L. Atherosclerosis: evidence for impairment of resolution of vascular inflammation governed by specific lipid mediators. The FASEB Journal. 2008;22(10):3595–3606. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-112201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Khoo N. K. H., Freeman B. A. Electrophilic nitro-fatty acids: anti-inflammatory mediators in the vascular compartment. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2010;10(2):179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schopfer F. J., Cole M. P., Groeger A. L., et al. Covalent peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ adduction by nitro-fatty acids: selective ligand activity and anti-diabetic signaling actions. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(16):12321–12333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m109.091512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bonacci G., Schopfer F. J., Batthyany C. I., et al. Electrophilic fatty acids regulate matrix metalloproteinase activity and expression. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(18):16074–16081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.225029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rader D. J. Molecular regulation of HDL metabolism and function: implications for novel therapies. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116(12):3090–3100. doi: 10.1172/jci30163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Feig J. E., Rong J. X., Shamir R., et al. HDL promotes rapid atherosclerosis regression in mice and alters inflammatory properties of plaque monocyte-derived cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(17):7166–7171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016086108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sanson M., Distel E., Fisher E. A. HDL induces the expression of the M2 macrophage markers arginase 1 and fizz-1 in a STAT6-dependent process. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8, article e74676) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee M. K. S., Moore X.-L., Fu Y., et al. High-density lipoprotein inhibits human M1 macrophage polarization through redistribution of caveolin-1. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2016;173(4):741–751. doi: 10.1111/bph.13319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kunjathoor V. V., Febbraio M., Podrez E. A., et al. Scavenger receptors class A-I/II and CD36 are the principal receptors responsible for the uptake of modified low density lipoprotein leading to lipid loading in macrophages. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(51):49982–49988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m209649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tertov V. V., Sobenin I. A., Gabbasov Z. A., et al. Multiple-modified desialylated low density lipoproteins that cause intracellular lipid accumulation. Isolation, fractionation and characterization. Laboratory Investigation. 1992;67(5):665–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miller Y. I., Choi S.-H., Wiesner P., et al. Oxidation-specific epitopes are danger-associated molecular patterns recognized by pattern recognition receptors of innate immunity. Circulation Research. 2011;108(2):235–248. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ivanova E. A., Bobryshev Y. V., Orekhov A. N. LDL electronegativity index: a potential novel index for predicting cardiovascular disease. Vascular Health and Risk Management. 2015;11:525–532. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s74697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moore K. J., Freeman M. W. Scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis: beyond lipid uptake. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2006;26(8):1702–1711. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000229218.97976.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Manning-Tobin J. J., Moore K. J., Seimon T. A., et al. Loss of SR-A and CD36 activity reduces atherosclerotic lesion complexity without abrogating foam cell formation in hyperlipidemic mice. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2009;29(1):19–26. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.176644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kruth H. S. Receptor-independent fluid-phase pinocytosis mechanisms for induction of foam cell formation with native low-density lipoprotein particles. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2011;22(5):386–393. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32834adadb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maxfield F. R., Tabas I. Role of cholesterol and lipid organization in disease. Nature. 2005;438(7068):612–621. doi: 10.1038/nature04399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chistiakov D. A., Bobryshev Y. V., Orekhov A. N. Macrophage-mediated cholesterol handling in atherosclerosis. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2016;20(1):17–28. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Feng B., Yao P. M., Li Y., et al. The endoplasmic reticulum is the site of cholesterol-induced cytotoxicity in macrophages. Nature Cell Biology. 2003;5(9):781–792. doi: 10.1038/ncb1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhu X., Owen J. S., Wilson M. D., et al. Macrophage ABCA1 reduces MyD88-dependent toll-like receptor trafficking to lipid rafts by reduction of lipid raft cholesterol. Journal of Lipid Research. 2010;51(11):3196–3206. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M006486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hägg D. A., Olson F. J., Kjelldahl J., et al. Expression of chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 18 in human macrophages and atherosclerotic plaques. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204(2):e15–e20. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yvan-Charvet L., Wang N., Tall A. R. Role of HDL, ABCA1, and ABCG1 transporters in cholesterol efflux and immune responses. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2010;30(2):139–143. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Calkin A. C., Tontonoz P. Transcriptional integration of metabolism by the nuclear sterol-activated receptors LXR and FXR. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2012;13(4):213–224. doi: 10.1038/nrm3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kappus M. S., Murphy A. J., Abramowicz S., et al. Activation of liver X receptor decreases atherosclerosis in Ldlr mice in the absence of ATP-binding cassette transporters A1 and G1 in myeloid cells. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2014;34(2):279–284. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Singh R., Kaushik S., Wang Y., et al. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature. 2009;458(7242):1131–1135. doi: 10.1038/nature07976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Razani B., Feng C., Coleman T., et al. Autophagy links inflammasomes to atherosclerotic progression. Cell Metabolism. 2012;15(4):534–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Liao X., Sluimer J. C., Wang Y., et al. Macrophage autophagy plays a protective role in advanced atherosclerosis. Cell Metabolism. 2012;15(4):545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gratchev A., Guillot P., Hakiy N., et al. Alternatively activated macrophages differentially express fibronectin and its splice variants and the extracellular matrix protein βIG-H3. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 2001;53(4):386–392. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gratchev A., Kzhyshkowska J., Köthe K., et al. Mφ1 and Mφ2 can be re-polarized by Th2 or Th1 cytokines, respectively, and respond to exogenous danger signals. Immunobiology. 2006;211(6–8):473–486. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gavrilin M. A., Mitra S., Seshadri S., et al. Pyrin critical to macrophage IL-1β response to Francisella challenge. The Journal of Immunology. 2009;182(12):7982–7989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]