Abstract

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and related opportunistic infections are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in susceptible population. This study aims to negate the paucity of data regarding the relation between CD4 levels, prevalence of enteric parasites, and the outcome of treatment with HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy) and Cotrimoxazole in Kerala, India. Multiple stool samples from 200 patients in a cross-sectional study were subjected to microscopy and Cryptosporidium stool antigen ELISA. Parasites were identified in 18 samples (9%). Cystoisospora and Cryptosporidium spp. were seen in 9 cases (4.5%) and 5 cases (2.5%), respectively. Microsporidium spores and Chilomastix mesnili cysts were identified in 1 case each (0.5% each). Seven cases of Cystoisospora diarrhoea recovered after treatment with Cotrimoxazole. Diarrhoea due to Cryptosporidium spp. in all 5 cases subsided after immune reconstitution with HAART. This study concludes that a positive association was seen between low CD4 count (<200 cells/μL) and overall parasite positivity (P value < 0.01). ELISA is a more sensitive modality for the diagnosis of Cryptosporidium diarrhoea. Chilomastix mesnili, generally considered a nonpathogen, may be a cause of diarrhoeal disease in AIDS. Immune reconstitution and Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis remain to be the best therapeutic approach in AIDS-related diarrhoea.

1. Introduction

Infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and its end stage, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), is a major public health challenge of modern times. Diarrhoea caused by parasites is one of the major opportunistic illnesses in HIV/AIDS resulting in significant morbidity. It diminishes patients' quality of life and if persistent causes dehydration, poor nutrition, and weight loss. Diarrhoea has been associated with 50% of HIV/AIDS patients in the developed world and in up to 100% of patients residing in developing countries [1]. The etiological enteric parasitic agents vary from patient to patient and from country to country depending on the geographical distribution, endemicity, seasonal variation of pathogens, and also the immune status of the patient [1].

HIV and parasitic infections may interact and mutually affect one another and parasitoses may facilitate the progression from asymptomatic HIV infection to AIDS. The common immunopathogenetic basis for the deleterious effects that parasitic diseases may have on the natural history of HIV infection involves a preferential activation of the T helper (Th2) type process. Thus the control of parasitic diseases is also necessary to aid in combating the HIV pandemic [2].

Since the start of the HIV epidemic, around 78 million people have become infected and 39 million have died of AIDS-related illnesses [3]. In 2013, of the 4.8 million people living with HIV in Asia and the Pacific, 250 000 died of AIDS-related causes [3]. India accounts for 51% of all AIDS-related deaths in the region [3].

There is paucity of data on relationship of CD4 levels and HIV/AIDS status with prevalence of enteric parasites among the HIV patients from Kerala, India. The present study therefore aims to determine the profile of enteric parasites and to study their association with immune status in HIV patients registered at the antiretroviral treatment centre of a tertiary care hospital in Kerala. Emphasis is also given on the comparison between various diagnostic techniques.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted among 200 HIV seropositive patients registered at the antiretroviral treatment centre of Government Medical College Kozhikode, over a period of one year from January 2013 to December 2013. A clinical workup comprising history, WHO staging of the disease, antiretroviral treatment status, presence or absence of diarrhoea, Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, and source of drinking water was constructed using a structured questionnaire. Flow cytometry (CyFlow Counter, Partec) was used to assess the CD4 T cell count and expressed as cells per cubic millimetre of blood (cells/μL).

A minimum of three feces samples were obtained from each patient on separate days. Concentration was done by formol ether sedimentation technique. Microscopy of wet mount and smear preparation was carried out before and after concentration. Smears were stained by Kinyoun's acid-fast method, rapid field stain, and modified trichrome stain (Ryan Blue method) for detection of trophozoites and cyst forms of parasites including the spores of Microsporidia. Cryptosporidium antigen stool ELISA (DRG Instruments GmbH, Frauenbergstr. 18, 35039 Marburg) was performed on samples with CD4 T cell count <200. Bacterial and fungal culture was done on all samples to rule out nonparasitic infectious causes of diarrhoea.

3. Results

Of the 200 HIV positive stool samples studied, 136 (68%) were of males and 64 (32%) were of females. 91 patients (45.5%) had acute or chronic diarrhoea and 109 (54.5%) patients did not have diarrhoea. 147 patients (73.5%) included in the study were on ART and 53 patients (26.5%) were ART naive. 58 (29%) were on Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis and the rest of the subjects were not on Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis. 37 subjects (74%) with severe immunosuppression (CD4 count <200) presented with diarrhoea and 26 subjects (34.2%) with no immunosuppression (CD4 count >500) presented with diarrhoea (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results.

| Patient characteristics | All patients (n = 200) | Patients with intestinal parasites (n = 18) | Patients without intestinal parasites (n = 182) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender male, n (%) | 136 (68%) | 17 (94.4%) | 119 (65.4%) | 0.012 |

| WHO staging of HIV, n (%) | 0.076 | |||

| Stage 1 | 11 (5.5%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (6%) | |

| Stage 2 | 34 (17%) | 2 (11%) | 32 (17.6%) | |

| Stage 3 | 145 (72.5%) | 13 (72.2%) | 132 (72.5%) | |

| Stage 4 | 10 (5%) | 3 (16.7%) | 7 (3%) | |

| Diarrhoea, n (%) | 91 (45.5%) | 15 (83.3%) | 76 (41.8%) | 0.001 |

| Immune status, n (%) | 0.000 | |||

| No immunosuppression (CD4 > 500 cells/µL) | 76 (38%) | 1 (5.6%) | 75 (41.2%) | |

| Mild immunosuppression (CD4 350–499 cells/µL) | 40 (20%) | 3 (16.7%) | 37 (20.3%) | |

| Advanced immunosuppression (CD4 200–349 cells/µL) | 34 (17%) | 2 (11.1%) | 32 (17.6%) | |

| Severe immunosuppression (CD4 < 200 cells/µL) | 50 (25%) | 12 (66.7%) | 38 (20.9%) | |

| HAART, n (%) | 147 (73.5%) | 13 (72.2%) | 134 (73.6%) | 0.898 |

| Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, n (%) | 57 (28.5%) | 5 (27.8%) | 52 (28.6%) | 0.943 |

| Drinking water, n (%) | 0.004 | |||

| Boiled water | 87 (43.5%) | 2 (11.1%) | 85 (46.7%) | |

| Tap water | 113 (56.5%) | 16 (88.9%) | 97 (53.3%) |

WHO, World Health Organisation; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

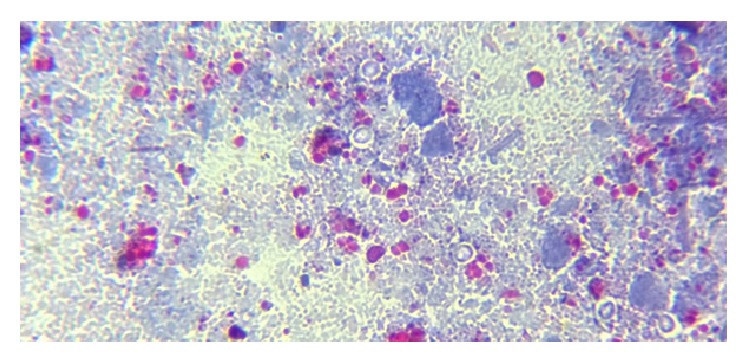

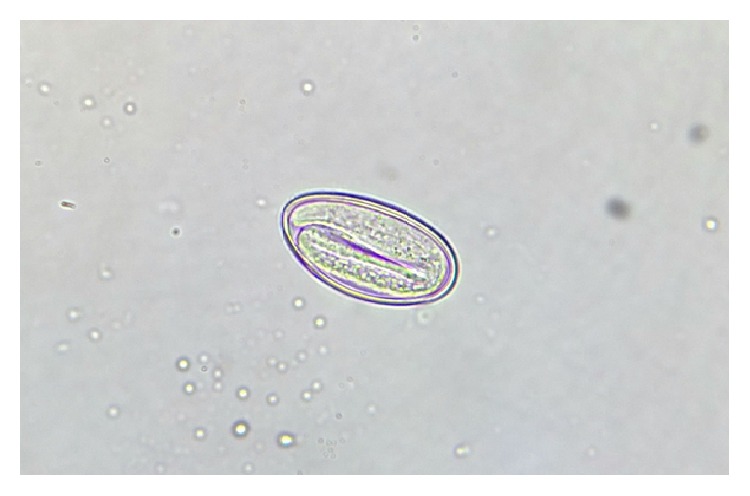

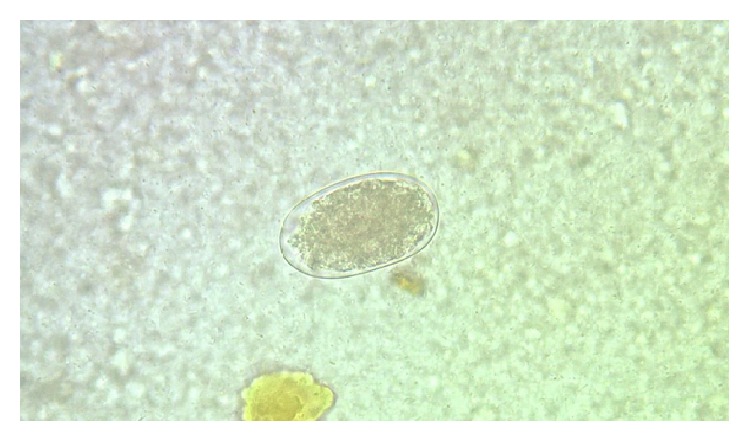

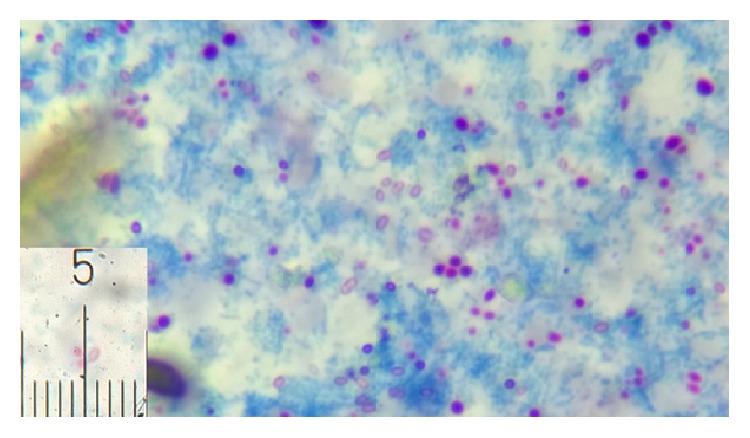

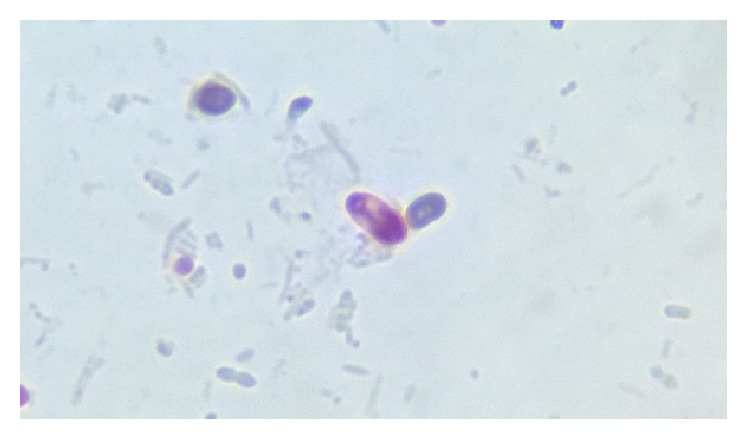

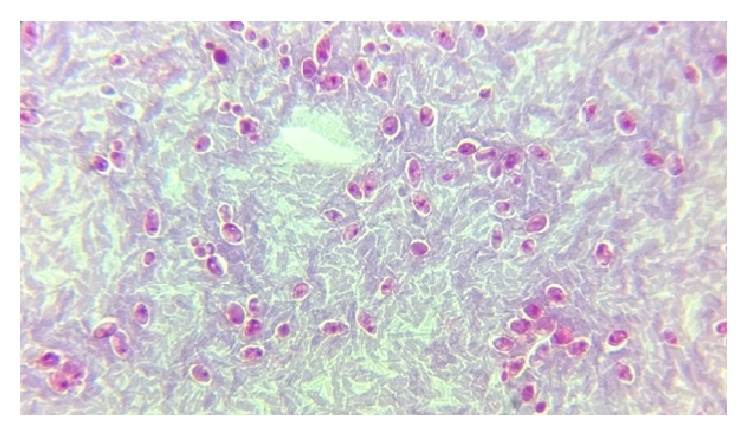

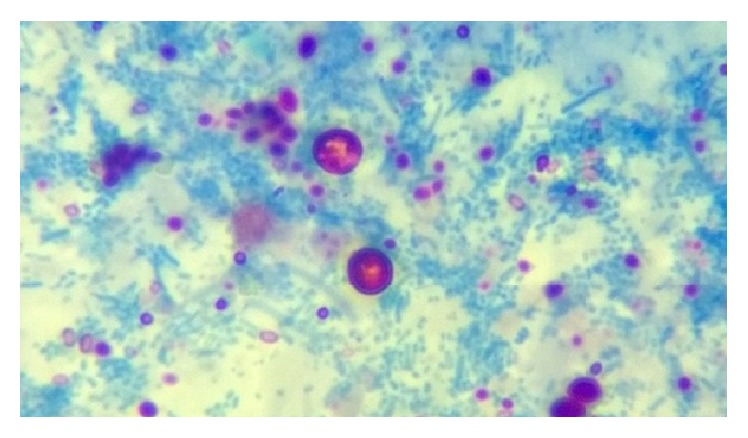

Parasites were identified in 18 samples (9%). Cystoisospora oocysts (Figures 1 –3) were identified in 9 cases (4.5%) and Cryptosporidium oocysts (Figures 4 and 5) in 5 cases (2.5%). Enterobius vermicularis worm (Figures 6 and 7) and ova (Figure 8) were identified in 2 cases (1%) and hookworm ova (Figure 9), Microsporidium spores (Figures 10 and 11), and Chilomastix mesnili cysts (Figure 12) in 1 case each (0.5% each). One subject had mixed infection with both Cryptosporidium spp. and Microsporidium spp. (Figure 13). This study shows a positive association of low CD4 count with diarrhoea and parasite positivity (both with P value < 0.01). Also majority of the parasite positive cases (83.3%) presented with diarrhoea (P value = 0.001).

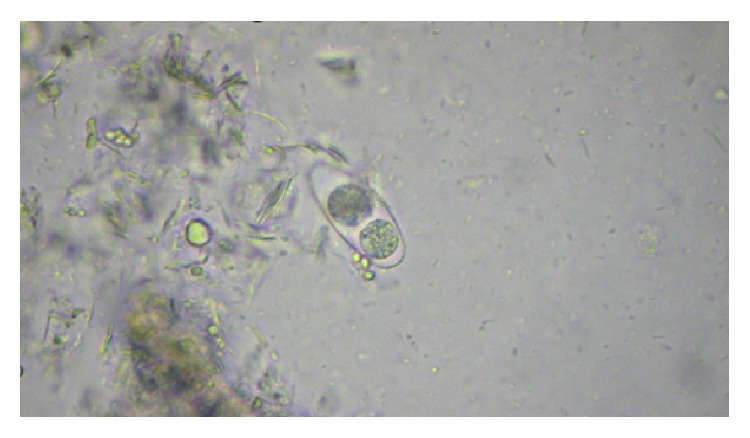

Figure 1.

Mature Cystoisospora oocyst on normal saline wet mount, under high power.

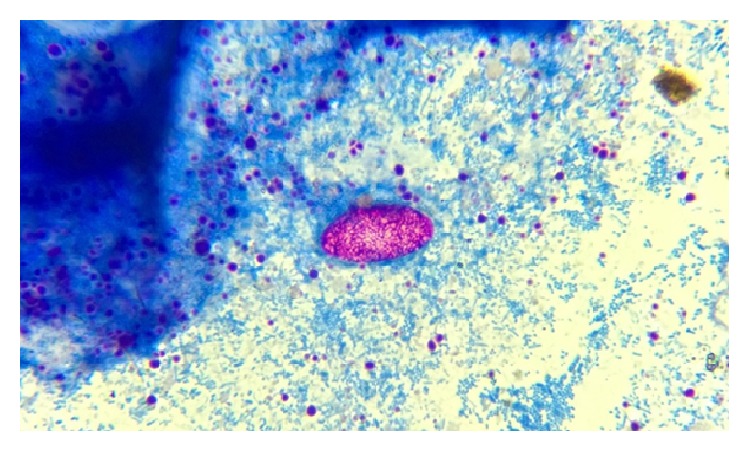

Figure 2.

Immature Cystoisospora oocyst on modified acid-fast stain, under oil immersion.

Figure 3.

Mature Cystoisospora oocyst with two sporoblasts on modified acid-fast stain, under oil immersion.

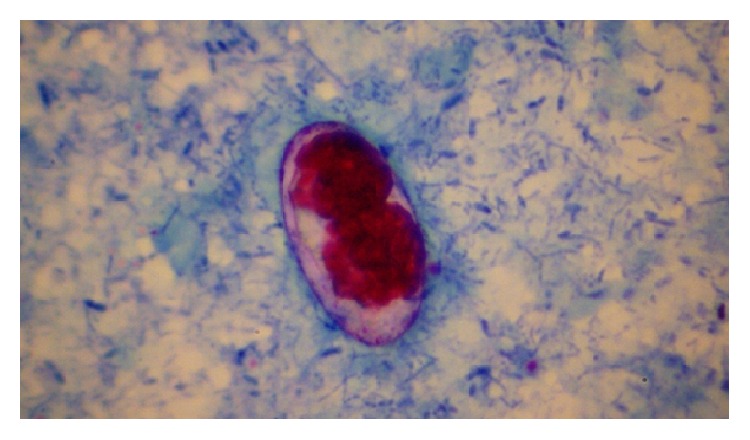

Figure 4.

Cryptosporidium oocysts on modified acid-fast stain, under oil immersion.

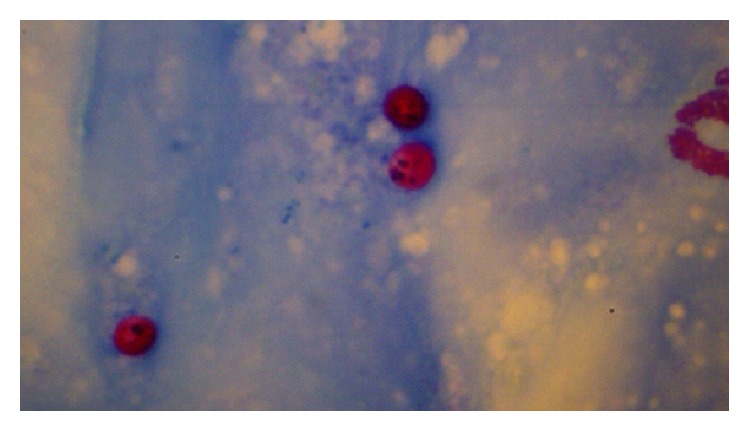

Figure 5.

Cryptosporidium oocysts appearing as unstained structures on modified trichrome stain, under oil immersion.

Figure 6.

Cervical alae of Enterobius vermicularis, under low power.

Figure 7.

Double bulb oesophagus of Enterobius vermicularis, under low power.

Figure 8.

Non-bile-stained ovum of Enterobius vermicularis with larva inside on normal saline wet mount, under high power.

Figure 9.

Non-bile-stained ovum of hookworm with segmented embryo inside on normal saline wet mount, under high power.

Figure 10.

Microsporidial spores stained reddish pink with horizontal stripe measuring 1.9 μm (inset) on modified acid-fast stain, under oil immersion.

Figure 11.

Magnified view of microsporidial spore on modified trichrome stain, under oil immersion.

Figure 12.

Cysts of Chilomastix mesnili on modified trichrome stain, under oil immersion.

Figure 13.

Variably acid-fast Cryptosporidium oocysts and microsporidial spores on modified acid-fast stain, under oil immersion.

All Cryptosporidium oocyst positive cases in this study were seen in subjects with a CD4 cell count <200 (severe immunosuppression). Thus there is a positive association between Cryptosporidium positivity in stool and a CD4 cell count of <200 (P value = 0.002). On the other hand, there is no significant association between CD4 cell count <200 (severe immunosuppression) and Cystoisospora positivity in this study (P value of 0.06).

Only 2 cases of Cryptosporidium diarrhoea were diagnosed by modified acid-fast staining of stool samples, whereas 5 cases were diagnosed to have Cryptosporidium diarrhoea by stool antigen ELISA (Table 2). The study shows that stool ELISA is a better diagnostic modality than stool modified acid-fast stain for the diagnosis of Cryptosporidium (P value < 0.01). The 9 cases of Cystoisospora infection in this study were demonstrated by both wet mount and modified acid-fast stain. In all the 9 cases, Cystoisospora oocysts were demonstrated in modified acid-fast stain on primary examination itself. But in only 5 cases, oocysts were demonstrated at preliminary examination by wet mount, the other 4 being demonstrated in wet mount on retrospective examination. The Cystoisospora oocysts in these 5 cases, 2 cases of Enterobius vermicularis, and 1 case of hook worm were the only parasites demonstrated on wet mount before concentration. In all the other cases, parasites were demonstrated either on wet mount or by staining of concentrated samples only.

Table 2.

Cryptosporidium positive cases.

| Age & sex | Cryptosporidium stool antigen ELISA positivity | Modified acid-fast positivity | CD4 count (cells/µL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 35/male | Yes | No | 40 |

| 54/male | Yes | Yes | 17 |

| 38/male | Yes | No | 132 |

| 38/male | Yes | No | 32 |

| 69/male∗ | Yes | Yes | 54 |

∗This case presented as mixed infection along with Microsporidium spp.

One of the Cryptosporidium positive cases and 6 of the Cystoisospora positive cases (38.9%) were identified on repeated stool sample examination only. One case positive for Cystoisospora was identified on examination of the sixth stool sample.

Of the five patients diagnosed to have Cryptosporidium infection, diarrhoea subsided in four, after a change of ART regimen from ZLN (Zidovudine, Lamivudine, and Nevirapine) to TLE (Tenofovir, Lamivudine, and Efavirenz). Fifth patient had complete remission of symptoms after he was started on first-line ART. No other treatment specific for Cryptosporidium was instituted in these patients.

Two patients out of nine who were diagnosed with Cystoisospora infection succumbed to the disease and expired. Out of these two patients, Cotrimoxazole could not be given to one because of hypersensitivity reactions and the other continued to have diarrhoea despite therapy with Cotrimoxazole. The rest of the seven patients became symptom-free after they were started on Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis as per National AIDS Control Organisation guidelines.

In this study bacterial culture for Salmonella, Shigella, and Vibrio cholerae yielded no pathogen. Fungal culture was also negative for opportunistic fungi causing diarrhoea.

4. Discussion

In Asia, the highest numbers of HIV-infected individuals belong to India and China [4]. The most common parasites causing diarrhoea in HIV-infected individuals include Cryptosporidium parvum, Isospora belli, Microsporidium spp., Giardia intestinalis, Entamoeba histolytica, and Strongyloides stercoralis [4]. This study determined the profile of intestinal parasites among HIV positive individuals and attempted to investigate whether the distribution of parasites was affected by immune status. Also, different diagnostic techniques were compared to determine the more effective and practical one to be used in resource poor settings.

Majority of the subjects in the study were males (68%). Studies from other parts of India also show a higher proportion of males among HIV-infected population (61%–64%) [5, 6]. This male preponderance should be because of the propensity of males to travel outside hometown for work and greater exposure to promiscuous and unprotected sex. Diarrhoea was seen in 45.5% of the subjects which is consistent with the data available from developing countries [7–9]. Overall parasite positivity in the study was 9%. The prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in HIV-infected patients from developing countries ranges from 12% to 38% [9–12]. The lower prevalence of parasites reported in this study could be due to the fact that stool examinations were performed whether or not the patients had diarrhoea. In this study, among patients with diarrhoea, the parasite positivity was 16%.

Cystoisospora was identified in maximum number of cases followed by Cryptosporidium in this study. In various studies conducted in north India and other countries, the most common parasite was Cryptosporidium [13, 14]. But studies from south India had findings similar to the one in this study [15, 16]. This difference may be attributed to the variation in geographical habitat of parasites and climate. Mixed infection with Cryptosporidium and Microsporidium was seen in one patient identified by both modified acid-fast staining and modified trichrome staining. Studies substantiate the fact that mixed infection with Cryptosporidium spp. and Microsporidium spp. is indeed common among HIV positive population [17–19]. Positive association between a CD4 count of <200 (severe immunosuppression) and parasite positivity in general was seen in this study (P value < 0.01). This association was not seen in case of Cystoisospora positive cases. These findings are corroborated in studies conducted worldwide [9, 14, 20, 21]. Chilomastix mesnili cysts were identified in one patient with CD4 count <200 cells/μL, showing the pathogenic nature of this otherwise nonpathogenic parasite in HIV patients [22]. The nature of periodic shedding of parasites necessitates multiple stool sample examinations for accurate diagnosis [23].

Immune reconstitution with HAART is the best therapeutic approach in diarrhoea due to Cryptosporidium. Even though treatment with Cotrimoxazole is effective for diarrhoea caused by Cystoisospora, a possibility of Cotrimoxazole resistant cystoisosporiasis should be borne in mind [24, 25].

This study shows a positive association between consumption of tap water and parasite positivity (P value = 0.004). Two subjects consuming boiled water at home also were diagnosed with parasitosis. This can be attributed to the unreliability of quality of water and food that one is exposed to, while travelling in a developing country like India. In a study conducted in Nepal, although a statistically significant association between the source of drinking water and parasite positivity was not seen, 20% of those taking direct tap water for drinking purposes and 12.5% of those using bore well water had intestinal parasitosis [10].

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the importance of routine screening for intestinal parasites in the stool of HIV patients with severe immunosuppression and diarrhoeal symptoms. Diarrhoea due to Cystoisospora is more common in south Indian settings. Mixed infections with Cryptosporidium and Microsporidium are not uncommon, necessitating a high index of suspicion and the use of different staining methods. While there was a positive association between severe immunosuppression and Cryptosporidium positivity, no such association was seen in case of cystoisosporiasis. ELISA is a better modality for the diagnosis of Cryptosporidial diarrhoea and should be included in the diagnostic depository where possible. Chilomastix mesnili, generally considered a nonpathogen, may be a cause of diarrhoeal disease in HIV positive population. The association of Cystoisospora infection with mortality necessitates the prompt institution of Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis and effective supportive therapy. In diarrhoea due to Cryptosporidium, treatment should always be aimed at immune reconstitution.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Jha A. K., Uppal B., Chadha S., et al. Clinical and microbiological profile of HIV/AIDS cases with diarrhea in North India. Journal of Pathogens. 2012;2012:7. doi: 10.1155/2012/971958.971958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winn W., Jr., Allen S., Janda W., et al. Koneman's Color Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. 6th. chapter 22. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3. UN AIDS Fact Sheet 2014.

- 4.Chavan N. S., Chavan S. N. Intestinal parasitic infections in HIV infected patients. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 2014;3(2):265–270. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandey A., Sahu D., Bakkali T., et al. Estimate of HIV prevalence and number of people living with HIV in India 2008-2009. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000926.e000926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishnu S., Bandyopadhyay D., Samui S., et al. Assessment of clinico-immunological profile of newly diagnosed HIV patients presenting to a teaching hospital of eastern India. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2014;139(6):903–912. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta S., Narang S., Nunavath V., Singh S. Chronic diarrhoea in HIV patients: prevalence of coccidian parasites. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2008;26(2):172–175. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.40536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Framm S. R., Soave R. Agents of diarrhea. Medical Clinics of North America. 1997;81(2):427–447. doi: 10.1016/S0025-7125(05)70525-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiwari B. R., Ghimire P., Malla S., Sharma B., Karki S. Intestinal parasitic infection among the HIV-infected patients in Nepal. Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2013;7(7):550–555. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amatya R., Shrestha R., Poudyal N., Bhandari S. Opportunistic intestinal parasites and CD4 count in HIV infected people. Journal of Pathology of Nepal. 2011;1:118–121. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pavie J., Menotti J., Porcher R., et al. Prevalence of opportunistic intestinal parasitic infections among HIV-infected patients with low CD4 cells counts in France in the combination antiretroviral therapy era. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2012;16(9):e677–e679. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.05.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asma I., Johari S., Benedict L. H. S., Yvonne A. L. L. How common is intestinal parasitism in HIV-infected patients in Malaysia? Tropical Biomedicine. 2011;28(2):400–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oguntibeju O. O. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in HIV-positive/AIDS patients. Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2006;13(1):68–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Missaye A., Dagnew M., Alemu A., Alemu A. Prevalence of intestinal parasites and associated risk factors among HIV/AIDS patients with pre-ART and on-ART attending dessie hospital ART clinic, Northeast Ethiopia. AIDS Research and Therapy. 2013;10(1, article 7) doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukhopadhya A., Ramakrishnan B. S., Kang G., et al. Enteric pathogens in southern Indian HIV-infected patients with and without diarrhoea. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 1999;109:85–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar S. S., Ananthan S., Saravanan P. Role of coccidian parasites in causation of diarrhoea in HIV infected patients in Chennai. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2002;116:85–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia L. S., Shimizu R. Y., Bruckner D. A. Detection of microsporidial spores in fecal specimens from patients diagnosed with cryptosporidiosis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1994;32(7):1739–1741. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1739-1741.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De A., Patil K., Mathur M. Detection of enteric parasites in HIV positive patients with diarrhea. Indian Journal of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2009;30(1):55–56. doi: 10.4103/0253-7184.55483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber R., Sauer B., Lüthy R., Nadal D. Intestinal coinfection with Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Cryptosporidium in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected child with chronic diarrhea. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1993;17(3):480–483. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuli L., Gulati A. K., Sundar S., Mohapatra T. M. Correlation between CD4 counts of HIV patients and enteric protozoan in different seasons—an experience of a tertiary care hospital in Varanasi (India) BMC Gastroenterology. 2008;8, article 36 doi: 10.1186/1471-230x-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janagond A. B., Sasikala G., Agatha D., Ravinder T., Thenmozhivalli P. R. Enteric parasitic infections in relation to diarrhoea in HIV infected individuals with CD4 T cell counts <1000 cells/μl in Chennai, India. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2013;7(10):2160–2162. doi: 10.7860/jcdr/2013/5837.3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morimoto N., Korenaga M., Komatsu C. A case report of an overseas-traveller’s diarrhoea probably caused by Chilomastix mesnili infection. Japanese Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1996;24(3):177–180. doi: 10.2149/tmh1973.24.177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cartwright C. P. Utility of multiple-stool-specimen ova and parasite examinations in a high-prevalence setting. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1999;37(8):2408–2411. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2408-2411.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miao Y. M., Gazzard B. G. Management of protozoal diarrhoea in HIV disease. HIV Medicine. 2000;1(4):194–199. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1293.2000.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mudholkar V. G., Namey R. D. Heavy infestation of Isospora belli causing severe watery diarrhea. Indian Journal of Pathology and Microbiology. 2010;53(4):824–825. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.72091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]