Abstract

Aim of the study

Aim of the study was to investigate interleukin (IL)-4 serum levels in patients with advanced endometriosis and whether IL-4 promoter region (-590C/T) genetic polymorphism is involved in genetic susceptibility to endometriosis.

Material and methods

IL-4 serum levels and IL-4 -590C/T genetic polymorphism were determined for 80 patients with advanced endometriosis and 85 healthy fertile women using a multiplex cytokine kit, with a Luminex 200 system; high molecular weight genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes, and further analyzed by PCR amplification and restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-PFLP). The relationship between IL-4 serum levels, genotypes and haplotypes and the presence of endometriosis was explored.

Results

Interleukin 4 serum levels were significantly higher in the endometriosis group compared to controls (138,459 compared to 84,710, p < 0.001). No significant difference was observed in IL-4 serum levels between genotypes. There were no differences in IL-4 -590C/T genotypes and allele frequencies between control women and patients with endometriosis (χ2 = 0.496, and χ2 = 0.928, OR = 1.3636, CI: 0.725-2.564).

Conclusions

The results suggest that in patients with advanced stages of endometriosis there is a higher serum level of IL-4, and that this value, or the presence of the disease, is not influenced by the presence of IL-4 -590C/T genetic polymorphism.

Keywords: endometriosis, genetic polymorphism, cytokine, interleukin

Introduction

Endometriosis is a complex gynecological disorder, often associated with chronic problems such as dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and infertility, characterized by a multifactorial involvement of genetic, hormonal, immunological and environmental components. Histogenesis of endometriosis is still not completely understood, and it is generally accepted that retrograde menstruation plays a central role, being present in almost 90% of women. On the other hand, while most women have retrograde menstruation to some extent, only about 6-10% will develop endometriosis [1–3]. Morphologically, it is characterized by the implantation and growth of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity. Endometriosis is experienced by around 10% of women of reproductive age and up to 30-50% of infertile women [4].

The exact pathophysiology of endometriosis is still unclear, but both environmental and genetic factors have been implicated in the occurrence and progression of the disease. Family studies regarding endometriosis have indicated an increased risk for close relatives of patients with endometriosis, thus suggesting that genetics might have a contribution [5]. Moreover, some very recent studies have implicated certain genetic polymorphisms in the development and progression of endometriosis [6–8], although the exact genes involved are still unknown.

A recent theory regarding endometriosis pathophysiology is suggesting that it is an inflammatory disease, which is involving a shift towards Th2-type immune response. Th2 cytokines (interferon γ – IFN-γ, interleukin 10 – IL-10) serum and peritoneal levels were significantly higher in patients with endometriosis compared to those free of disease [9, 10].

Interleukin 4 and IL-10 family are the main Th2 cytokines, having a known anti-inflammatory effect. Several lines of evidence indicate that Th2 immune response is associated with endometriosis. Interleukin 4 is a cytokine with both stimulatory and inhibitory effects on the inflammatory system, such as macrophage inhibition and T-cell activation. Increased concentrations of IL-4 were previously reported in endometriotic tissues and elevated levels of IL-4 were observed in patients with endometriosis, both in plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) supernatants. On the other hand, no difference was found between IL-4 concentrations in women with different stages of endometriosis [11, 12]. A very recent study investigating serum and peritoneal fluid (PF) immunological markers in adolescent girls with chronic pelvic pain found that adolescents with endometriosis had significantly higher concentrations of IL-4 [13]. In the same line, a study aimed to investigate a possible role of IL-4 in the development of endometriosis suggested that proliferation of endometriotic stromal cells induced by locally produced IL-4 is involved in the development of endometriosis [14].

Regarding the serum and peritoneal levels of IL-4 in endometriosis, one could speculate that women having a pathological secretion of IL-4, which could be determined by a genetic polymorphism of the gene encoding IL-4, may be more susceptible to develop endometriosis. The gene encoding IL-4 has been mapped on chromosome 5 and, moreover, a polymorphism consisting of a C to T exchange at position 590 upstream from the open reading frame (-590C/T), that is associated with greater luciferase activity has been described [15]. Previous studies involving IL-4 (-590C/T) genetic polymorphism have found a negative correlation with endometriosis [16, 17].

In the present study, we have investigated IL-4 serum levels in patients with advanced endometriosis and whether IL-4 promoter region (-590C/T) genetic polymorphisms are involved in a genetic susceptibility to endometriosis.

Material and methods

Design

A case-control study was conducted and included 165 patients divided into two groups as follows: Group I (endometriosis group) – 80 women with regular menses and with no history of pelvic infections, autoimmune and neoplastic diseases, undergoing laparoscopy or laparotomy for suspected endometriosis. Histopathological examination established the endometriosis diagnosis for all included patients. The severity of endometriosis was staged according to the revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) classification; all included patients were staged III or IV according to rASRM; Group II (control group) – 85 healthy non-pregnant women aged between 18-40 years old, without clinical and para-clinical evidence of endometriosis, undergoing laparoscopy for unexplained infertility or tubal ligation. Exclusion criteria: patients with previous pelvic surgeries, history of cancer, suspected malignancy, adenomyosis or leiomyoma, pre-surgical suspicion of evidence of premature ovarian failure, or the use of the ovarian suppressive drug, such as oral contraceptives, GnRH agonists, progestins or danazol in the preceding 6 months were excluded from the study. None of the patients had taken anti-inflammatory medications or had been diagnosed with an inflammatory or infectious condition for ≥ 6 months before the study.

The study design was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of “Iuliu Haţieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, and signed informed consent was received from each woman before sample collection. The study was conducted under the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration. 10 ml of venous blood was collected from each patient on an empty stomach, which was centrifuged and the serum obtained was stored at –70oC for future determinations. 5 patients were excluded from the endometriosis group because not enough blood was harvested at inclusion in the study.

Cytokine evaluation

We used multiplex cytokine kits (Invitrogen Human Cytokine 30-Plex Panel, LHC6003) in order to measure serum levels of IL-4. Measurements were performed with a Luminex 200 system (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's specifications (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The sensitivity of the test was specified by the manufacturer (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The average sensitivity of the test was < 0.5 pg/ml, with an inter-assay variation coefficient of 8.7%.

Genomic DNA analysis

High molecular weight genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes, using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen), according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. Genotyping of the IL-4 polymorphism, located at -590 in the gene promoter, was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) – restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), as previously described, with minor modifications [16]. DNA amplification was performed in a final volume of 50 µl, containing 100 ng genomic DNA, 0.25 mM of each dNTP, 0.5 µM of each primer (5’-TAAACTTGGGAGAACATGGT-3’ for the upstream primer and 5’-TGGGGAAAGATAGAGTAATA-3’ for the downstream primer), 1.25 units of Taq polymerase (JumpStart™ Taq DNA Polymerase, Sigma) and 5 µl of 10X PCR buffer. The concentration of MgCl2 was 2.5 mM.

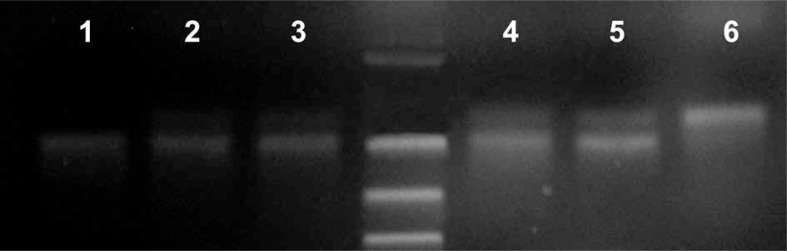

The following thermocycling conditions were used: 5 min at 94°C, followed by 32 cycles of amplification consisting of 45 seconds at 94°C, 45 seconds at 49°C and 45 seconds at 72°C, followed by a final elongation step of 7 min at 72°C, in a S1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad). PCR products (195 bp) were digested with the restriction enzyme AvaII (New England Biolabs), generating the following fragments: 175 and 20 bp for the homozygous -590 CC genotype, 195, 175 and 20 bp for the heterozygous -590 CT genotype and 195 bp for the homozygous -590 TT genotype. Restriction fragments were separated by electrophoresis on a 3.3% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel, CDC Epi Info 7 and IBM SPSS software (version 22.0). Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or absolute and relative frequencies for the groups. Using the Shapiro-Wilk test we found that IL-4 levels displayed a mix of normal and non-normal distributions, therefore the group comparisons were performed with non-parametric tests: Mann-Whitney U test for independent samples and Kruskal-Wallis test for multiple group comparison; also Pearson χ2 test with and without the continuity correction, and Fisher exact test were used as statistical tests. P values less than 0.05 were regarded as significant.

Results

Genotyping by RFLP of the IL-4 -590 C/T polymorphism was successfully achieved for all subjects (Fig. 1). Genotype frequencies were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in the control group (χ2 test p = 0.073) but not in the endometriosis group (χ2 test p = 0.023). The distribution of genotypes and of the allele frequencies in the endometriosis group did not differ statistically from those in the control group (27.5% C/C, 55.0% C/T, and 17.5% T/T versus 40.0, 45.0 and 15.0 respectively) (Table 1). χ2 test probability was 0.496, showing no significant differences in genotype distribution, and 0.928 for the presence or absence of the mutant allele. Odds ratio for the presence of the mutant allele was 1.3636 (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Electrophoresis gel image for the IL-4 -590 C/T polymorphism: 1 – homozygous patient -590 TT, 2-5 – heterozygous patients -590 CT, 6 – wild type allele -590 CC

Table 1.

Distribution of genotypes and alleles of the IL-4 -590C/T polymorphism in healthy control women and patients with endometriosis

| Polymorphism | Allele | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | CT | TT | Total | C | T | ||

| Endometriosis group | n | 22 | 44 | 14 | 80 | 88 | 72 |

| % | 27.5% | 55.0% | 17.5% | 100.0% | 46.81% | 54.55% | |

| Control group | n | 32 | 36 | 12 | 80 | 100 | 60 |

| % | 40.0% | 45.0% | 15.0% | 100.0% | 53.19% | 45.45% | |

| Total | n | 27 | 40 | 13 | 160 | 188 | 132 |

| % | 33.8% | 50.0% | 16.3% | 100.0% | 58.75% | 41.25% | |

Table 2.

Odds ratio for TT and CT genotypes as risk factors for endometriosis

| Polymorphism | OR (95% CI) | χ2 p-value |

|---|---|---|

| TT vs. CC | 1.697 (0.447-6.439) | 0.435 |

| TT vs. CT | 0.955 (0.272-3.351) | 0.942 |

| CT vs. CC | 1.778 (0.662-4.778) | 0.252 |

OR – odds ratio; CI – confidence interval

The Mann-Whitney U test shows a significantly higher serum IL-4 level in the endometriosis group (138.459 compared to 84.710 in the control group, p < 0.001). For the IL-4 grouping by case/control the SPSS calculated observed power was 1.000.

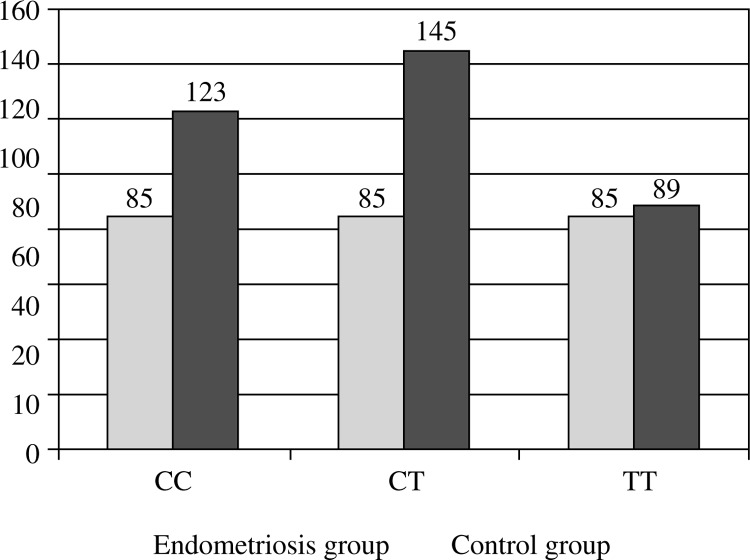

No significant difference in IL-4 serum levels between genotypes was observed (Kruskal-Wallis probabilities for comparison inside the endometriosis group, the control group and applied globally were greater than 0.05) (Table 3). For the IL-4 grouping by genotype the SPSS observed power was 0.580 and 0.581 if grouping was done by genotype and case/control (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

IL-4 serum levels for each group: comparison by genotypes and alleles

| Genotypes | Alleles | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC Mean (SD) |

CT Mean (SD) |

TT Mean (SD) |

Kruskal-Wallis comparison |

C Mean (SD) |

T Mean (SD) |

Mann-Whitney U test |

|

| Endometriosis group | 172.99 (121.90) | 131.53 (61.87) | 114.86 (55.37) | 0.416 | 150.66 (93.33) | 124.86 (58.33) | 0.217 |

| Control group | 84.73 (2.48) | 84.52 (2.00) | 85.20 (0.92) | 0.519 | 84.66 (2.28) | 84.80 (1.65) | 0.241 |

| Global | 116.50 (82.62) | 110.500 (51.304) | 101.169 (42.070) | 0.802 | 113.91 (69.96) | 106.709 (47.34) | 0.846 |

SD – standard deviation

Fig. 2.

Median values of IL-4 by genotype

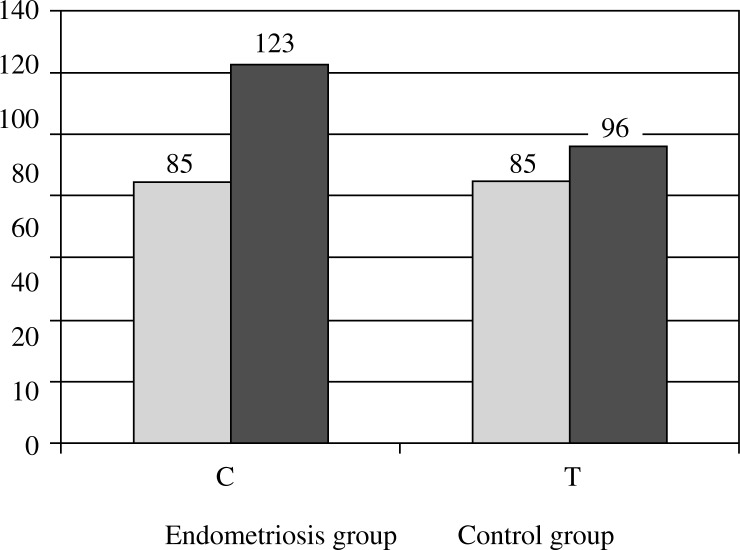

We have found no significant difference between IL-4 serum levels corresponding to different alleles (Mann-Whitney U probabilities for comparison inside the endometriosis group, the controls group and applied globally was greater than 0.05) (Table 3). In the case of IL-4 grouping by alleles, SPSS observed power was 0.290, and 0.295 if grouping was done by genotype and case/control (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Median values of IL-4 by allele

Discussion

Endometriosis is a common gynecological disease involving the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus, and despite intensive research, the cause of endometriosis remains unknown. Different theories on the endometriosis pathogenesis involve growth factors and pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory cytokines associated with the regulation of cell multiplication and neoangiogenesis. It has been suggested that immunological abnormalities are associated with the presence and development of endometriosis [18–20], and a role of cytokines [21] was emphasized, high levels of many interleukins being found in patients with endometriosis [9, 22, 23]. A recent study by Podgaec et al. has described an increased level of IFN-γ and IL-10 in patients with endometriosis [9] with a predominance of IL-4 and IL-10 when considering the ratio between cytokine levels, thus reflecting a potential shift towards Th2 immune responses. On the other hand, genetic and hereditary basis for endometriosis was previously evidenced by Bellelis et al. [24]. It is understood that cytokine gene polymorphisms could affect the serum levels of cytokines by influencing transcriptional regulation. The role of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in some immunological disorders has been previously reported [25–27], and some exact genetic polymorphisms have been identified in relation with endometriosis.

The present study has investigated a possible association between IL-4 -590C/T genetic polymorphisms and endometriosis, and whether IL-4 serum levels are modified in patients with advanced endometriosis. The results showed a significantly higher serum level of IL-4 in patients with advanced endometriosis compared to healthy controls, thus suggesting an association between the IL-4 serum levels and endometriosis. The study did not find any association between severe endometriosis and the presence of IL-4-590C/T promoter polymorphism.

A series of studies performed in the last decade emphasized the changes in the PF and serum cytokines levels from endometriotic women. Particularly, a recent study has found significantly higher concentrations of PF and serum IL-4 [13]. Moreover, Antsiferova et al. have found that endometriosis development is associated with an increased intra-cellular mRNA expression and synthesis of IL-4 and IL-10 in peripheral lymphocytes. Also, the same changes were observed for IL-4 in ectopic endometrium of women with endometriosis [28], and an increased IL-4 production in peritoneal fluid of patients with endometriosis which normalized after hormone therapy [29, 30]. At the same time, other authors did not observe any significant difference in serum and PF IL-4 levels between normal and early- and late-stage endometriosis [31]. Our results are confirming some of the previous studies as we also found an increased IL-4 serum level in patients with endometriosis.

Regarding genetic involvement, to our knowledge, there are only two previous studies focusing on IL-4 genetic polymorphism and association with endometriosis. Both Kitawaki et al. and Hsieh et al. found no association between IL-4 -590C/T polymorphism and the presence or the severity of endometriosis, though both studies were done on patients of Asian origin. Our study confirms the same results, adding to the previous ones the fact that it included patients of Caucasian origin.

A limitation of our study could be the lack of differentiation between patients with ovarian endometrioma (OE) and patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE). Due to the profile of our clinic, all included patients were diagnosed with OE with or without associated DIE, and not only DIE patients. Ovarian endometrioma and DIE are considered two distinct entities of endometriotic disease, and thus endometriosis can progress to cystic ovarian disease and pelvic adhesions in some women, and to deeply infiltrating disease in other women, and sometimes to both stages of severe disease in the same woman [32]. Studies on pro-inflammatory cytokines showed differences between patients with OE and DIE. In consequence, some differences could be present in relation with anti-inflammatory cytokines as well, and so our results regarding IL-4 serum levels could be influenced by the lack of cleavage of the two forms of the disease. A strength of the present study could be represented by the fact that all included patients were of Caucasian origin, while the previous studies used only patients of Asian origin. It is worth highlighting that a genetic association, although valid for a specific ethnic population, may not be relevant to individuals of another ethnicity.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates a higher serum level of IL-4 in patients with advanced stages of endometriosis compared with patients free of disease. At the same time, we have shown that the -590C/T polymorphism of the IL-4 gene is not associated with advanced stage endometriosis, suggesting no involvement for this polymorphism in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Although our study, together with the previous ones, shows the same non-involvement result for IL-4 genetic polymorphism in the susceptibility to endometriosis, the higher serum level of IL-4 in patients with endometriosis, points to the necessity for further studies to elucidate the role of IL-4 in the pathogenesis of this vicious disease.

Identifying factors that contribute to the pathogenesis of endometriosis could have practical importance in selecting subjects at risk and possibly those predisposed to more severe forms. At the same time, excluding some of the possibly involved factors narrows the search to a possible prediction factor for endometriosis. Further studies with a larger number of patients and different ethnic groups are required for a better understanding of the endometriosis pathogenesis.

This paper was published under the project funded by “Iuliu Hatieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, internal grant no. 1491/7/28.01.2014

References

- 1.Chae SJ, Lee GH, Choi YM, et al. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and interleukin-6 gene polymorphisms in patients with advanced-stage endometriosis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2004;70:34–39. doi: 10.1159/000284398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sampson JA. Peritoneal endometriosis due to menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1927;14:422–469. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364:1789–1799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cramer DW, Missmer SA. The epidemiology of endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;955:11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy S. The genetics of endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;82:129–133. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun S, Kim H, Ku SY, et al. The association between endometriosis and polymorphisms in the interleukin-1 family genes in Korean women. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2012;68:154–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2012.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallegos-Arreola MP, Figuera-Villanueva LE, Puebla-Pérez AM, et al. Association of TP53 gene codon 72 polymorphism with endometriosis in Mexican women. Genet Mol Res. 2012;11:1401–1408. doi: 10.4238/2012.May.15.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luisi S, Galleri L, Marini F, et al. Estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms are associated with recurrence of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:764–766. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Podgaec S, Abrao MS, Dias JA, Jr, et al. Endometriosis: an inflammatory disease with a Th2 immune response component. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1373–1379. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan W, Li S, Chen Q, et al. Association between interleukin-10 promoter polymorphisms and endometriosis: a meta-analysis. Gene. 2013;515:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin H, Wang S, Dai S. Study on interferon gamma and interleukin-4 contents of plasma and cultured monoclear cell supernatants in patients with endometriosis. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2000;35:327–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gazvani MR, Bates MD, Vince GS, et al. Peritoneal fluid concentrations of interleukin-4 in relation to the presence of endometriosis, its stage and the phase of the menstrual cycle. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:361–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drosdzol-Cop A, Skrzypulec-Plinta V, Stojko R. Serum and peritoneal fluid immunological markers in adolescent girls with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2012;67:374–381. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e31825cb12b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.OuYang Z, Hirota Y, Osuga Y, et al. Interleukin-4 stimulates proliferation of endometriotic stromal cells. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:463–469. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenwasser LJ, Klemm DJ, Dresback JK, et al. Promoter polymorphisms in the chromosome 5 gene cluster in asthma and atopy. Clin Exp Allergy. 1995;25(Suppl 2):74–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1995.tb00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitawaki J, Koshiba H, Kitaoka Y, et al. Interferon-gamma gene dinucleotide (CA) repeat and interleukin-4 promoter region (-590C/T) polymorphisms in Japanese patients with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1765–1769. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh YY, Chang CC, Tsai FJ, et al. Polymorphisms for interleukin-4 (IL-4) -590 promoter, IL-4 intron3, and tumor necrosis factor alpha -308 promoter: non-association with endometriosis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2002;16:121–126. doi: 10.1002/jcla.10021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trovó de Marqui AB. Genetic polymorphisms and endometriosis: contribution of genes that regulate vascular function and tissue remodeling. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2012;58:620–632. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302012000500022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malutan AM, Costin N, Diculescu D, et al. Gene polymorphism involment in endometriosis. Gineco.eu. 2014;38:158–161. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falconer H, D'Hooghe T, Fried G. Endometriosis and genetic polymorphisms. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62:616–628. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000279293.60436.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harada T, Iwabe T, Terakawa N. Role of cytokines in endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01816-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fairbanks F, Abrão MS, Podgaec S, et al. Interleukin-12 but not interleukin-18 is associated with severe endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:320–324. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Podgaec S, Dias Junior JA, Chapron C, et al. Th1 and Th2 immune responses related to pelvic endometriosis. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2010;56:92–98. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302010000100022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellelis P, Dias JA, Jr, Podgaec S, et al. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of pelvic endometriosis – a case series. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2010;56:467–471. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302010000400022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amirzargar AA, Bagheri M, Ghavamzadeh A, et al. Cytokine gene polymorphism in Iranian patients with chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Int J Immunogenet. 2005;32:167–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2005.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amirzargar AA, Rezaei N, Jabbari H, et al. Cytokine single nucleotide polymorphisms in Iranian patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17:84–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rezaei N, Amirzargar AA, Shakiba Y, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine gene single nucleotide polymorphisms in common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;155:21–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03790.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mier-Cabrera J, Jiménez-Zamudio L, García-Latorre E, et al. Quantitative and qualitative peritoneal immune profiles, T-cell apoptosis and oxidative stress-associated characteristics in women with minimal and mild endometriosis. BJOG. 2011;118:6–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu CC, Yang BC, Wu MH, Huang KE. Enhanced interleukin-4 expression in patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:1059–1064. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81439-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szyllo K, Tchorzewski H, Banasik M, et al. The involvement of T lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of endometriotic tissues overgrowth in women with endometriosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2003;12:131–138. doi: 10.1080/0962935031000134842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hassa H, Tanir HM, Tekin B, et al. Cytokine and immune cell levels in peritoneal fluid and peripheral blood of women with early- and late-staged endometriosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279:891–895. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0844-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bulun SE. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:268–279. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]