Summary

Background

There are thousands of survivors of the 2014 Ebola outbreak in west Africa. Ebola virus can persist in survivors for months in immune-privileged sites; however, viral relapse causing life-threatening and potentially transmissible disease has not been described. We report a case of late relapse in a patient who had been treated for severe Ebola virus disease with high viral load (peak cycle threshold value 13·2).

Methods

A 39-year-old female nurse from Scotland, who had assisted the humanitarian effort in Sierra Leone, had received intensive supportive treatment and experimental antiviral therapies, and had been discharged with undetectable Ebola virus RNA in peripheral blood. The patient was readmitted to hospital 9 months after discharge with symptoms of acute meningitis, and was found to have Ebola virus in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). She was treated with supportive therapy and experimental antiviral drug GS-5734 (Gilead Sciences, San Francisco, Foster City, CA, USA). We monitored Ebola virus RNA in CSF and plasma, and sequenced the viral genome using an unbiased metagenomic approach.

Findings

On admission, reverse transcriptase PCR identified Ebola virus RNA at a higher level in CSF (cycle threshold value 23·7) than plasma (31·3); infectious virus was only recovered from CSF. The patient developed progressive meningoencephalitis with cranial neuropathies and radiculopathy. Clinical recovery was associated with addition of high-dose corticosteroids during GS-5734 treatment. CSF Ebola virus RNA slowly declined and was undetectable following 14 days of treatment with GS-5734. Sequencing of plasma and CSF viral genome revealed only two non-coding changes compared with the original infecting virus.

Interpretation

Our report shows that previously unanticipated, late, severe relapses of Ebola virus can occur, in this case in the CNS. This finding fundamentally redefines what is known about the natural history of Ebola virus infection. Vigilance should be maintained in the thousands of Ebola survivors for cases of relapsed infection. The potential for these cases to initiate new transmission chains is a serious public health concern.

Funding

Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust.

Introduction

There are thousands of survivors of the 2014 Ebola virus disease epidemic in west Africa.1 Previous Ebola outbreaks were much smaller and occurred in resource-limited locations, so it would be unsurprising if the full range of complications has yet to be documented. However, the possibility of a late, severe clinical relapse of Ebola virus infection, with the potential for onward transmission, was not anticipated.

Here, we describe a case of late relapse in a patient who had been treated for severe Ebola virus disease with high viral load.

Patient history

Initial admission (December, 2014, to January, 2015)

Pauline Cafferkey, a 39-year-old female nurse from Scotland, had assisted the humanitarian effort in Sierra Leone, where she provided direct patient care. After her return to Glasgow, UK, in December, 2014, the patient was diagnosed with Ebola virus disease; plasma Ebola virus RNA was detected by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR),2 with a cycle threshold value of 24·8. She was transferred to the high-level isolation unit at the Royal Free Hospital, London, UK, on day 2 of her illness. She received intravenous fluid and electrolyte replacement, one dose of oral brincidofovir (200 mg), and two doses of convalescent plasma (300 mL) on consecutive days. Her clinical condition deteriorated over the next 3 days, with type 1 respiratory failure that required continuous positive airway pressure ventilation, erythroderma, mucositis, large volume diarrhoea, and agitation. Total parenteral nutrition was started through a central venous catheter. Plasma Ebola virus RNA peaked with a cycle threshold value of 13·2 on day 6. Monoclonal antibody therapy specific for Ebola virus glycoprotein (ZMAb;3 Public Health Agency of Canada, MB, Canada) was given (total dose 50 mg/kg) on days 5 and 8. Subsequently, plasma Ebola virus RNA declined and was lower than the limit of assay detection by day 25. Pauline was discharged from hospital on day 28 with significant fatigue and an ongoing hypercoaguable state with thrombocytosis, treated with low-molecular-weight heparin and aspirin.4

Convalescence after initial admission (January to October, 2015)

3 weeks after discharge, the patient had not gained weight and had a resting tachycardia of 110 beats per min; thyroid function tests confirmed the clinical diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis (thyroxine [T4] 33·9 pmol/L [normal range 9–21], triiodothyronine [T3] 4·0 nmol/L [0·9–2·5], and suppressed thyroid stimulating hormone <0·01 mU/L [0·35–5]). An iodine thyroid uptake scan showed low uptake consistent with thyroiditis. Antithyroid peroxidase and thyroid receptor antibodies were negative, whereas thyroglobulin was elevated. Propranolol was prescribed for symptomatic control, and over the next 8 weeks the patient became clinically and biochemically euthyroid. 10 weeks after discharge, severe hair loss (acute telogen effluvium) required prescription of a wig. Over the next 4 months, Pauline's symptoms improved without specific treatment and she returned to work as a community nurse.

6 months after discharge, she developed severe bilateral ankle, knee, and hip pain and swelling. MRI confirmed small bilateral ankle joint effusions. Ultrasound-guided aspiration of the right ankle joint was planned to test for Ebola virus, but no effusions could be detected by ultrasound on the day of the procedure, and aspiration was not attempted. Antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factor were negative. Ebola virus RNA was not detected in blood or vaginal swabs taken at this time. The arthralgic symptoms were controlled by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and gradually resolved over the following 2 months. Pauline continued working during this time.

Ebola virus relapse and second admission (October to November, 2015)

9 months after discharge, the patient developed rapid-onset severe headache with neck pain, photophobia, fever, and vomiting. She was readmitted to hospital in Glasgow on day 2, with worsening headache, photophobia, neck stiffness, and fever up to 38·5°C. She was fully orientated (Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15/15) and complete neurological examination was unremarkable. She had no ocular symptoms and had not travelled outside Europe since being discharged from hospital. Admission blood tests revealed mild neutrophilia and lymphopenia, and mildly raised C-reactive protein (figure 1). Testing for HIV infection was negative. Lumbar puncture showed a slightly raised opening pressure (24 cm H2O), but only limited analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was done because of possible infection risk to laboratory staff. White blood cells were noted on microscopy of a fixed sample of CSF, but were not quantified or characterised. PCR was negative for Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, varicella zoster virus, enterovirus, and parechovirus. Ebola virus RNA was detected by RT-PCR at a high level in CSF (cycle threshold value 23·7) and at a much lower level in plasma (31·3). Ebola virus relapse causing meningitis was diagnosed and the patient was medically evacuated to the Royal Free Hospital high-level isolation unit on day 5 of illness.

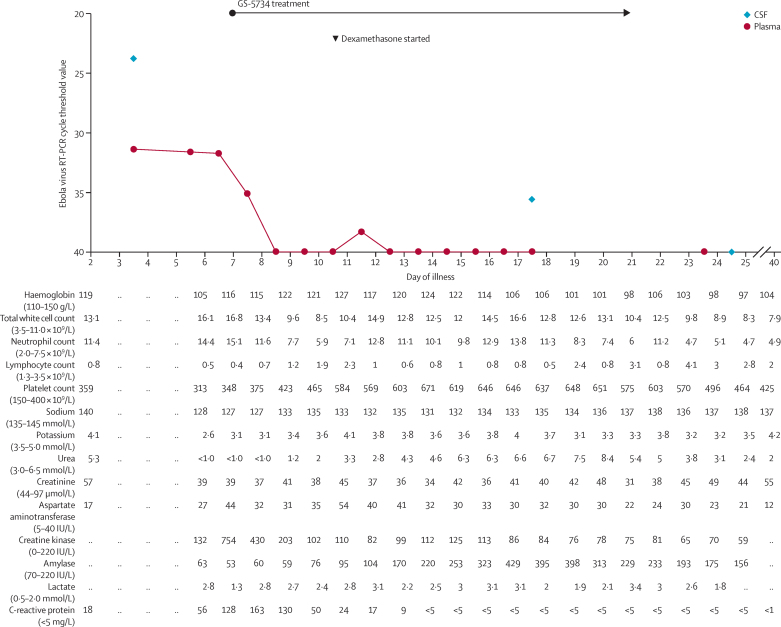

Figure 1.

Clinical laboratory findings over the course of Ebola virus relapse

RT-PCR=reverse transcriptase PCR.

Methods

Early supportive and symptomatic therapy

During the 90 min air transfer from Glasgow to London, the patient had two self-terminating tonic-clonic seizures. On arrival at the high-level isolation unit, a central venous catheter was inserted into the right internal jugular vein, and a loading dose of phenytoin was given. Regular levetiracetam treatment was started via a nasogastric tube. A urinary catheter was placed, and intravenous fluids and enteral feeding were started. Secondary bacterial infection was considered due to rising peripheral white blood cell count and CRP (figure 1), with aspiration pneumonia following the seizures being a probable cause, and intravenous amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (co-amoxiclav) started. Prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin was given subcutaneously.

Specific antiviral therapy

In view of detectable Ebola virus RNA in peripheral blood, we gave monoclonal antibody therapy specific to the Ebola virus glycoprotein, knowing this would not cross the blood–brain barrier and treat the primary condition. The available preparation, MIL77 (Beijing Mabworks, Beijing, China), was started on day 5. The intention was to give a total dose of 3249 mg (50 mg/kg) by slow, escalating, dose infusion; however, after infusion of only 60 mg, Pauline rapidly became pyrexial (38·7°C), tachycardic (heart rate 150 beats per min) and hypoxaemic (SpO2 fell from 96% to 86% on room air) with diffuse facial and truncal erythema. An allergic reaction to monoclonal antibody therapy rechallenge was diagnosed, the infusion stopped, and intravenous hydrocortisone and chlorphenamine given. The acute symptoms resolved completely over the next 2 h, and no further MIL77 was given.

In view of the severity of clinical illness, we started treatment on day 7 of illness with the experimental nucleoside analogue GS-5734 (Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA, USA), on the basis of potent anti-Ebola virus activity in vitro, encouraging but scant preclinical safety data in humans, and successful treatment of Ebola virus infection in non-human primates.5 Data for drug penetration into the CNS were not available. Approval for emergency compassionate use was obtained through an established internal clinical review and governance process, and included fully informed patient consent. On the basis of existing preclinical data, we started treatment with a once-daily infusion of 150 mg GS-5734 over 2 h; after the third infusion, this dose was increased to 225 mg in view of further preclinical safety data. GS-5734 treatment was given for a total of 14 days (figure 1). No serious adverse clinical or biochemical events from GS-5734 treatment were detected. A small rise in serum amylase was noted from day 5 of GS-5734 treatment, peaking at 429 IU/L (normal range 70–220 IU/L) 6 days later and then falling during continued GS-5734 treatment (figure 1).

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and the corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

On days 5–10 of illness, the patient developed worsening head and thoracolumbar pain, and became progressively more agitated. Pain control with oxycodone and ketamine infusions and enteral gabapentin was only partly effective, and the patient required sedation with a propofol infusion. She developed subacute onset of double vision and slurred speech, in addition to bilateral VI, left pupillary-sparing partial III, left upper motor neuron VII cranial nerve palsies, and mostly left-sided cerebellar signs. There were no long tract signs. By day 10, Pauline had fluctuating consciousness with hypoventilation despite cessation of sedative drugs and reversal of opiate effects with naloxone. Brain imaging was not available at this stage because of strict biocontainment precautions. The clinical findings were compatible with skull-base leptomeningeal inflammation with encephalitis. High-dose intravenous dexamethasone (8 mg immediately then 4 mg three times daily) was therefore started.

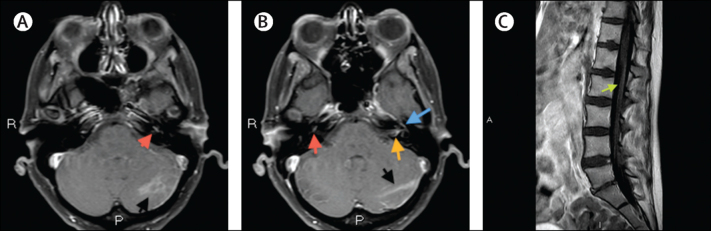

From day 11 to day 35, the neurological deficits slowly improved and the steroid dose was gradually reduced. The patient reported dizziness, tinnitus, and reduced hearing in her left ear, suggesting involvement of the left VIII cranial nerve. Profound fatigue persisted, but consciousness level normalised and cranial nerve palsies partly resolved. Bladder voiding was impaired, and patchy leg weakness (particularly of left-hip flexion, with global areflexia) restricted her ability to mobilise unaided. Contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain and spine on day 31 showed patchy leptomeningeal enhancement, mainly involving the brainstem, cranial nerves, cauda equina, and conus medullaris, with abnormal signal and enhancement within the left cerebellar hemisphere (figure 2). Mobility slowly improved with physiotherapy, and the urinary catheter was successfully removed. Pauline was discharged from hospital after 52 days, with residual weakness of the left leg and left-sided deafness.

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced MRI of the head and spine

Gadolinium-enhanced, fat-suppressed, 3 mm axial T1-weighted images of the brain showing: abnormal area of enhancement within the left cerebellar hemisphere (black arrow) and abnormal enhancement of the left cochlea basal turn (red arrow; A); and abnormal enhancement within the left cerebellar hemisphere (black arrow), right cochlea basal turn (red arrow), anterior genu of the tympanic segment of the left facial nerve (blue arrow), and focus of enhancement within the left internal auditory canal (orange arrow; B). Gadolinium-enhanced 4 mm sagittal T1-weighted image of the lumbar spine showing enhancement involving the surface of conus and along the cauda equina (green arrow; C).

Plasma Ebola virus RNA cycle threshold values remained remarkably constant on days 4–6 of illness, and then declined rapidly to lower than the detection limit (cycle threshold value >40; figure 1). The first recorded decline, on day 7 of illness, preceded the first dose of GS-5734 on the same day. CSF examinations were repeated on days 16 and 24 of illness; on both occasions, opening pressure was normal. CSF white cell counts were 38 × 106/L on day 16 and 13 × 106/L on day 24. Ebola virus RNA remained detectable in CSF at a low level (cycle threshold value 35·6) on day 16 (after 10 days of GS-5734 treatment), but was undetectable on day 24 (4 days after completion of the 14 day treatment course). Infectious virus was recovered from the day 4 CSF, but not from the day 16 or day 24 samples. No infectious virus was detected in any blood samples (appendix).

We previously reported the full-length genomic sequence of the Ebola virus responsible for the patient's initial illness.6 Ebola virus from CSF and plasma from the time of relapse was resequenced with an unbiased metagenomic approach to investigate the possibility of development of immune escape mutants in the intervening 10 months (appendix). However, next-generation sequencing of plasma and CSF revealed only two non-coding changes, present and identical in both samples, compared with the original sequence from plasma (NCBI accession numbers KU052669 and KU052670; appendix). No other pathogen sequences were detected in CSF or blood, excluding co-infection at the time of Ebola virus relapse.

Circulating Ebola virus-specific antibodies were present following the initial illness in January, 2015, which persisted in convalescence. As expected, antibodies against Ebola virus glycoprotein, nucleocapsid protein, and VP40 matrix protein were present, indicating that despite monocolonal antibody therapy against Ebola virus glycoprotein the patient mounted a broad, endogenous humoral response. After relapse, a significant anamnestic response was detected by day 9 of illness, with a two-log rise in total antibody titre when compared with convalescence. Serological assays and results are also described in the appendix.

Discussion

Fatigue, arthralgia, and ocular complications, including uveitis, are not uncommon in survivors of Ebola virus disease.7, 8 However, the pathogenesis of post-Ebola complications, in particular the presence and role of viral persistence, is unknown. The potential for persistence in immune-privileged sites is inferred from prolonged detection of Ebola virus RNA in semen,9 and, in another case, Ebola virus was detected in aqueous humour 14 weeks after initial diagnosis.10 However, to our knowledge, no previous reports exist of late severe relapses of Ebola virus with viral RNA redetected in blood.

In the present case, both CSF and plasma tested positive for Ebola virus RNA 10 months after the initial diagnosis. We believe that the primary site of viral relapse was the CNS because the clinical syndrome was compatible with meningoencephalitis, the level of viral RNA was greater in the CSF than in plasma, and infectious virus was recovered from the first CSF sample. The CNS was probably infected at the time of original illness, which has been reported in another case,11 and persisted in this immune-privileged site. Notably, no neurological symptoms were reported during convalescence until the abrupt onset of meningitis. We do not know in which specific site or cells the virus persisted, or whether the virus continuously replicated there or reactivated to produce clinical relapse. Sequence comparison at the time of initial illness and subsequent relapse showed no changes in coding regions, excluding an immune escape variant of the virus causing clinical relapse. A potential precipitant for relapse, such as intercurrent illness or use of immunosuppressive drugs, was not identified, and therefore its cause and timing remain unexplained.

An intriguing question is why similar illness has not been reported among the many thousands of survivors in west Africa. Clinical care and follow-up of survivors undoubtedly needs strengthening and it is possible that severe Ebola virus relapses have occurred but not been recognised or reported. However, in survivor cohorts under close research surveillance, the absence of severe relapses suggests that they are an unusual event. It is plausible that patients with very high Ebola viral loads, such as Pauline, are most likely to have immune-privileged sites of infection, such as the CNS, and therefore be at the greatest risk of relapse. Most of these patients would have succumbed to initial illness in west Africa.12, 13 We also cannot discount the possibility that treatment during Pauline's initial illness with passive immunotherapy (convalescent plasma and monoclonal antibody) increased the risk of subsequent CNS relapse. Convalescent plasma is effective in reducing mortality in Argentine haemorrhagic fever, caused by the Junin arenavirus, but its use is associated with a late neurological syndrome not seen in untreated patients.14, 15 Whether this late neurological syndrome is caused by CNS viral replication is unclear.

We treated this Ebola virus relapse first with monoclonal antibody therapy. Our patient is the first to be rechallenged with Ebola virus-specific monoclonal antibody therapy following previous treatment, and developed a life-threatening allergic reaction. Because the number of survivors who received monoclonal antibody treatment increased towards the latter part of the west Africa outbreak, recognition of the possibility of allergic reactions is important, although we do not yet know whether immunoallergic reactions to rechallenge are common. We subsequently used the nucleoside analogue GS-5734—its first use for Ebola virus infection in human beings. We did not detect any serious adverse clinical or laboratory effects from GS-5734 treatment in this case. With no other cases to define the natural history of untreated Ebola virus meningoencephalitis, we cannot know whether antiviral treatment altered the clinical course of disease. Topical and systemic steroids were used previously as part of treatment for uveitis caused by delayed Ebola virus relapse,10 and initiation of treatment with high-dose steroids in our case seemed to correlate with improvement in conscious level and neurological deficits. We are unable to assess our patient's risk of further Ebola virus relapse or know whether this has been reduced or eliminated by antiviral treatment. We detected a significant anamnestic antibody response during her relapse. Longitudinal studies of Ebola virus in semen suggest that virus is gradually cleared from immune-privileged sites over time without specific treatment.9 Taken together, we deem her risk of further relapse to be very low, but cannot exclude the possibility since the cause of her first relapse remains obscure.

A 2015 report16 describes sexual transmission of Ebola virus from the semen of a survivor 179 days after disease onset. Relapse of viral replication in the CNS alone would not pose a risk of onward community transmission, but our patient also had detectable Ebola virus RNA in blood. The level was much lower than in CSF, she had pre-existing circulating antibodies against Ebola virus, and we were unable to recover infectious virus from any blood sample. Therefore, the risk of infection to other people was probably small, and empirically much lower than during primary Ebola virus disease, but cannot be excluded. In view of the large number of Ebola survivors in west Africa, the potential for relapse, even if rare, to initiate new transmission chains is a serious public health concern. A small cluster of Ebola cases occurred in Liberia in November, 2015, after human to human transmission was thought to have ended, which WHO has reported was the result of re-emergence of Ebola virus that had persisted in a previously infected individual.17

Ongoing vigilance by all health-care professionals for relapsed Ebola virus infection in survivors is essential, as we do not yet know the full range of clinical illnesses that might result. A role for antiviral treatment in survivors with viral persistence or identified at greatest risk of relapse might need to be considered. Our case shows why good medical care, surveillance, and research in survivors should be crucial components of the global response to the devastating Ebola epidemic in west Africa.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The work was funded by the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, without external grants. The pharmaceutical companies Beijing MabWorks Biotech (China) and Gilead Sciences provided investigational medicines free of charge. These companies had no input into patient selection or clinical management, or this Article. Sequencing and bioinformatics analyses were funded by the Medical Research Council. ECT is funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 102789/Z/13/Z). We thank Pauline Cafferkey for consenting to publication of her case, and for her suggestions for the manuscript. We also thank Gary Kobinger (National Microbiology Laboratory of the Public Health Agency of Canada); Erin Quirk (Gilead Sciences); Breda Athan and staff of the high-level isolation unit; Stephen Powis, Steve Shaw, and staff of the intensive-care, patient-at-risk, high-level isolation unit laboratory and pharmacy teams at Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK; Liz Hughes and her nursing team at the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, Glasgow, UK; Gillian Mulholland and her nursing team at Gartnavel General Hospital, Glasgow, UK; the Royal Air Force Air Transportable Isolator Teams; and staff of the Virus Reference Department and Rare and Imported Pathogens Laboratory, Pubic Health England.

Contributors

MJ, DJB, SB, IC, SH, DK, RL, RSNL, FJ, AM, DM, NM, TM, SM, CP, DP, SEP, AR, DR, NDR, RAS, ECT, SW were involved in the care of the patient over the course of her two admissions and subsequent convalescence. AL, IJ, KT, MZ, MPat, RG did the virological and serological assays. ECT, AF, RJG, JH, RO, VBS, GSW, MPal, AL, MZ did viral sequencing and analysed the sequencing data. MJ did the literature research and wrote the first draft of the report, which was further edited by all authors. All authors had full access to the data and vouch for their integrity and accuracy. The authors were solely responsible for final review and approval of the report. The corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.WHO Ebola situation report. 20 January 2016. http://apps.who.int/ebola/current-situation/ebola-situation-report-20-january-2016 (accessed Jan 26, 2016).

- 2.Trombley AR, Wachter L, Garrison J, et al. Comprehensive panel of real-time TaqMan polymerase chain reaction assays for detection and absolute quantification of filoviruses, arenaviruses, and New World Hantaviruses. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:954–960. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qui X, Audet J, Wong G, et al. Successful treatment of Ebola virus-infected cynomolgus macaques with monoclonal antibodies. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:138ra81. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson AJ, Madox V, Rattenbury S, et al. Thromboelastography in the management of coagulopathy associated with Ebola virus disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;62:610–612. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren T, Jordan R, Lo M, et al. Once-daily treatment with GS-5734 initiated three days post viral challenge protects rhesus monkeys against lethal Ebola virus disease (EVD). ID Week; San Diego, CA, USA; Oct 7–11, 2015. LB-2 (abstr).

- 6.Bell A, Lewandowski K, Myers R, et al. Genome sequence analysis of Ebola virus in clinical samples from three British healthcare workers, August 2014 to March 2015. EuroSurveill. 2015;20:21131. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.20.21131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bwaka MA, Bonnet MJ, Calain P, et al. Ebola hemorrhagic fever in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo: clinical observations in 103 patients. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:S1–S7. doi: 10.1086/514308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark DV, Kibuuka H, Millard M, et al. Long-term sequelae after Ebola virus disease in Bundibugyo, Uganda: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:905–912. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deen GF, Knust N, Broutet FR, et al. Ebola RNA persistence in semen of Ebola virus disease survivors—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2015 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511410. published online Oct 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varkey J, Shantha J, Crozier I, et al. Persistence of Ebola virus in ocular fluid during convalescence. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2423–2427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howlett P, Brown C, Helderman T, et al. Ebola virus disease complicated by late-onset encephalitis and polyarthritis, Sierra Leone. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:150–152. doi: 10.3201/eid2201.151212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schieffelin JS, Schaffer JG, Goba A, et al. Clinical illness and outcomes in patients with Ebola in Sierra Leone. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2092–2100. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faye O, Andronico A, Faye O, et al. Use of viremia to evaluate the baseline case fatality ratio of Ebola virus disease and inform treatment studies: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001908. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maiztegui JI, Fernandez NJ, de Damilano AJ. Efficacy of immune plasma in treatment of Argentine Haemorrhagic Fever and association between treatment and a late neurological syndrome. Lancet. 1979;314:1216–1217. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enria D, Franco SG, Ambrosio A, Vallejos D, Levis S, Maiztegui J. Current status of the treatment of Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1986;175:173–176. doi: 10.1007/BF02122443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mate SE, Kugelman JR, Nyenswah TG, et al. Molecular evidence of sexual transmission of Ebola virus. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2448–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO Ebola situation report. 6 January 2016. http://apps.who.int/ebola/current-situation/ebola-situation-report-6-january-2016 (accessed Jan 26, 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.