Abstract

Key points

SLC17A9 proteins function as a lysosomal ATP transporter responsible for lysosomal ATP accumulation.

P2X4 receptors act as lysosomal ion channels activated by luminal ATP.

SLC17A9‐mediated ATP transport across the lysosomal membrane is suppressed by Bafilomycin A1, the V‐ATPase inhibitor.

SLC17A9 mainly uses voltage gradient but not pH gradient generated by the V‐ATPase as the driving force to transport ATP into the lysosome to activate P2X4.

Abstract

The lysosome contains abundant ATP which plays important roles in lysosome functions and in cell signalling. Recently, solute carrier family 17 member 9 (SLC17A9, also known as VNUT for vesicular nucleotide transporter) proteins were suggested to function as a lysosomal ATP transporter responsible for lysosomal ATP accumulation, and P2X4 receptors were suggested to be lysosomal ion channels that are activated by luminal ATP. However, the molecular mechanism of SLC17A9 transporting ATP and the regulatory mechanism of lysosomal P2X4 are largely unknown. In this study, we report that SLC17A9‐mediated ATP transport across lysosomal membranes is suppressed by Bafilomycin A1, the V‐ATPase inhibitor. By measuring P2X4 activity, which is indicative of ATP transport across lysosomal membranes, we further demonstrated that SLC17A9 mainly uses voltage gradient but not pH gradient as the driving force to transport ATP into lysosomes. This study provides a molecular mechanism for lysosomal ATP transport mediated by SLC17A9. It also suggests a regulatory mechanism of lysosomal P2X4 by SLC17A9.

Key points

SLC17A9 proteins function as a lysosomal ATP transporter responsible for lysosomal ATP accumulation.

P2X4 receptors act as lysosomal ion channels activated by luminal ATP.

SLC17A9‐mediated ATP transport across the lysosomal membrane is suppressed by Bafilomycin A1, the V‐ATPase inhibitor.

SLC17A9 mainly uses voltage gradient but not pH gradient generated by the V‐ATPase as the driving force to transport ATP into the lysosome to activate P2X4.

Abbreviations

- Baf‐A1

bafilomycin A1

- CBX

carbenoxolone

- DIDS

4,4′‐diisothiocyano‐2,2′‐stilbenedisulfonic acid

- GPN

glycyl‐phenylalanine 2‐naphthylamide

- Lamp1

lysosomal‐associated membrane protein 1

- SLC

solute carrier

- SLC17A9

solute carrier family 17 member 9

- V‐ATPase

vacuolar H+‐ATPase

- VNUT

vesicular nucleotide transporter

Introduction

The solute carrier (SLC) superfamily encodes membrane‐embedded proteins that regulate transport of many types of substances across the plasma membrane and the membranes of intracellular organelles. Among these, the SLC17 family of transporters is a group of nine structurally related proteins that mediate the transmembrane transport of organic anions. They play important roles in urate secretion (SLC17A1 and SLC17A3), lysosomal export of sialic acid (SLC17A5), and vesicular accumulation of aspartate (SLC17A5), glutamate (SLC17A5‐8) and ATP (SLC17A9, also known as vesicular nucleotide transporter, VNUT) (Fredriksson et al. 2008; Sawada et al. 2008; Hediger et al. 2013; Cao et al. 2014).

Recent studies indicate that lysosomes store large amounts of ATP (Zhang et al. 2007; Dou et al. 2012), and that SLC17A9/VNUT acts as the ATP transporter that mediates ATP accumulation in the lysosomes (Cao et al. 2014). However, the mechanisms of SLC17A9/VNUT‐mediated ATP transport across lysosomal membranes remains unclear. Previous studies have shown that vesicular neurotransmitter transporters take up neurotransmitters into synaptic vesicles or secretory vesicles using an electrochemical gradient of H+ established by the vacuolar H+‐ATPase (V‐ATPase) as the driving force (Sawada et al. 2008; El Mestikawy et al. 2011; Miyaji et al. 2011; Omote et al. 2011). As the lysosome membrane contains a large amount of V‐ATPase, we hypothesize that the lysosome may use the same mechanism to transport ATP across lysosomal membranes. Activation of lysosomal V‐ATPase creates both voltage gradient (ΔΨ, defined as V cytosol − V lumen; V lumen set at 0 mV) and pH gradient (ΔpH) across lysosome membranes. As such, the relative contribution of ΔΨ and ΔpH to lysosomal ATP transport is also important. In addition, P2X4 has been shown to be a lysosomal ion channel activated by ATP from the luminal side in a pH‐dependent manner (Huang et al. 2014). We suspect that lysosomal P2X4 may be regulated by SLC17A9.

In this study, we show that lysosomal SLC17A9‐mediated ATP transport and accumulation are inhibited by Bafilomycin A1 (Baf‐A1), a specific and potent inhibitor of V‐ATPase. This suggests that the electrochemical gradient of H+ established by the V‐ATPase is essential for SLC17A9 function. We also provide direct evidence that lysosomal P2X4 channels can be activated by ATP intake through SLC17A9. By using P2X4 as a measure of SLC17A9‐mediated ATP transport, we further show that ΔΨ but not ΔpH is the major driving force for SLC17A9‐mediated lysosomal ATP transport. Our data demonstrate a molecular mechanism for SLC17A9‐mediated lysosomal ATP transport, and also suggest a functional interaction between SLC17A9 and P2X4 in lysosomal membranes.

Methods

Cell culture and transfection

Cos1, an African green monkey kidney fibroblast‐like cell line, and C2C12, a mouse myoblast cell line, were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). They were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium: Nutrient Mixture F‐12 (DMEM/F12) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cos1 cells were transfected with P2X4‐GFP at a density of ∼70% confluency using Lipofectamine 3000 as per the supplier's instructions. C2C12 was transfected with P2X4‐GFP ± SLC17A9 shRNA or scrambled RNA by electroporation with the Neon Transfection System (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions (1650 V, 30 ms, one pulse). An 80–90% transfection efficiency was regularly achieved. For some experiments, cells were seeded on 0.01% poly‐lysine (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) coated coverslips for ∼12–24 h prior to further treatments.

Reagents

The following chemicals were used: Baf‐A1 (400 nm, Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO, USA), glycyl‐phenylalanine 2‐naphthylamide (GPN; 200 μm; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), TritonX‐100 (1%; Sigma), carbenoxolone (CBX; 20 μm; Sigma), 4,4′‐diisothiocyano‐2,2′‐stilbenedisulfonic acid (DIDS; 20 μm; Tocris Bioscience), Evans Blue (20 μm; Sigma), ATP disodium salt hydrate (Sigma), ADP sodium salt (Sigma), GTP salt hydrate (Sigma), Vacuolin‐1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and ivermectin (5 μm; Sigma). The following primary antibodies were used in Western blotting: rabbit‐anti‐SLC17A9 (1:1000, sc‐86311; Santa Cruz), anti‐Lamp1 (1:1000, 1D4B‐rat‐anti‐mouse, H4A3‐mouse‐anti‐human; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, IA, USA) and anti‐GAPDH (1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). HRP‐conjugated goat‐anti‐rat, goat‐anti‐rabbit and goat‐anti‐mouse antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz and Bio‐Rad (Hercules, CA, USA) and used at 1:2000 or 1:10,000 dilution, respectively.

Knockout of SLC17A9 using CRISPR/Cas9 system

The operation followed detailed instructions of the published protocol (Cong et al. 2013). In brief, 20 bp target single‐guide RNA sequences (gRNA) were obtained by screening monkey SLC17A9 mRNA sequence with CRISPR DESIGN online software (http://crispr.mit.edu/), and two sequences were chosen: AACCCGCTGAATAGACTGGC (target 1) and TTTGGGTGTGGTACGTGTAC (target 2). After being annealed with their reverse complementary sequences, the short double strand DNAs (hereafter gDNA) were ligated with BbsI digested pX330‐2A‐GFP and the new constructs named pX330‐2A‐GFP SLC17A9 gDNA1 and 2, respectively. Cos1 cells were transfected with pX330‐2A‐GFP (named SLC17A9 control) and individual pX330‐2A‐GFP/SLC17A9 gDNAs (named SLC17A9 KO) using Lipofectamine 3000 as per the supplier's instructions. After ∼48 h, SLC17A9 control and knockout cells were transfected again with P2X4 using Lipofectamine 3000. After another ∼24 h, cells were seeded or collected for further experiments.

Knockdown of SLC17A9 using shRNA

SLC17A9 was knocked down in C2C12 cells using shRNA as previously reported (Cao et al. 2014). Sequences for mouse SLC17A9‐shRNA were: no. 1 (5′‐GATCCCCCCTTCCTGACATTCTCTCGAATTCAAGAGATTCGAGAGAATGTCAGGAAGGTTTTTA‐3′) and no. 2 (5′‐AGCTTAAAAACCTTCCTGAC ATTCTCTCGAATCTCTTGAATTCGAGAGAATGTCAGGAAGGGGG‐3′). Scrambled RNA was purchased from Santa Cruz. C2C12 cells were transfected with SLC17A9‐shRNA or scrambled RNA using Lipofectamine 3000 as per the supplier's instructions. After ∼48 h, transfected cells were transfected again with P2X4 using Lipofectamine 3000. After another ∼24 h, cells were seeded or collected for further experiments.

Staining for ATP

Cos1 cells were pretreated with Baf‐A1 (400 nm) for 30 or 60 min, and then incubated with quinacrine (5 μm) for 30 min at 37°C and chased for 30 min. Images were acquired using a confocal microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with a 63× oil‐immersion objective and then collected and analysed using ZEN2012 software (Zeiss). A low laser power (< 0.5%) was used to minimize fluorescence bleaching.

Confocal microscopy

Confocal fluorescence images were taken using an inverted Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope with 10× plain or 63× oil‐immersion objectives. Sequential excitation wavelengths at 488 and 543 nm were provided by argon and helium–neon gas lasers, respectively. BP500‐550 and LP560 emission filters were used to collect green and red images in channels 1 and 2, respectively. Then, the images of the same cell were saved and analysed with ZEN software. Here, the term co‐localization refers to coincident detection of above‐background green and red fluorescent signal. Image size was set at 1024 × 1024 pixels. Intensity of fluorescence was analysed using Fiji (ImageJ) software.

Bioluminescence measurement of ATP and ATP uptake assay

The ATP concentration of freshly isolated lysosomes was measured in triplicate with a microplate luminometer (Fluoroskan Ascent FL Microplate Fluorometer and Luminometer, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using the adenosine 5′‐triphosphate Bioluminescent Assay kit (FLAA, Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A standard curve was established for each measurement. Samples were adjusted to pH 7.8 to establish conditions optimal to detect ATP. All samples were kept on ice before measurement. Briefly, 100 μl of the ATP assay mix solution was added to the assay tube and allowed to stand at room temperature for 3 min to hydrolyse endogenous ATP. Then, 100 μl of the sample was added rapidly, gently mixed and the plate was read immediately using a luminometer. Blank medium or buffer samples were read in parallel as background, which was subtracted from sample readings. For some experiments, freshly isolated lysosome fractions were treated with 200 μm GPN or 1% TritonX100 for 5 min at 4°C (to minimize ATP degradation) to lyse lysosomes. Samples containing the same amount of protein were loaded for ATP assay (75 μg protein per well).

For ATP uptake assays, 0.2 μl of 2 mm ATP was added to 100 μl of samples (containing 75 μg total protein) for an initial ATP concentration of 2 × 10−6 m. The sample's luminescence was read over time, and luminescence decay indicated active ATP uptake. Sample buffer served as blank, and the decay of intrinsic luminescence was measured as background. In some experiments, freshly isolated lysosomes from cells pretreated with the above described inhibitors for 30 min at 37°C were immediately assayed for ATP uptake in the presence of those inhibitors. At the end of the assay, 1% TritonX100 was added to each sample to measure the total ATP released from vesicles.

Lysosome isolation by subcellular fractionation

Lysosomes were isolated as described previously (Dong et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2012). Briefly, cell lysates were obtained by Dounce homogenization in a homogenizing (HM) buffer (0.25 m sucrose, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.0), and then centrifuged at 1500 g (4200 r.p.m.) (ST‐16R, F15 rotor; Fisher, Houston, TX, USA) at 4°C for 10 min to remove nuclei and intact cells. Postnuclear supernatants were then fractionated on a Percoll density gradient using a Beckman Optima L‐90 K ultracentrifuge. For that analysis the ultracentrifuge tube was layered with 2.5 m sucrose (bottom), 18% Percoll in HM buffer (middle) and sample (top). Samples were centrifuged at 90,000 g (31,300 r.p.m.) at 4°C for 1 h using a Beckman Coulter 70.1 Ti rotor to obtain light, medium and heavy membrane fractions. Heavy membrane fractions containing cellular organelles were further layered over a discontinuous iodixanol (27, 22.5, 19, 16, 12 and 8%, v/v) gradient generated by mixing iodixanol in HM buffer with 2.5 m glucose. Osmolarity of all solutions was 300 mOsm. After centrifugation at 4°C for 2.5 h at 180,000 g (44,200 r.p.m.), the sample was divided into 12 fractions (0.5 ml each) for further analyses. Fractions 1–5 were used as purified lysosomes. Biological properties and ionic composition of lysosomes were largely maintained during this procedure due to slowed transport across lysosomal membranes occurring at 4°C.

Western blot

Proteins were analysed using standard methods. Proteins derived from whole cells or lysosome lysates were resolved on 10% SDS‐PAGE. Proteins were then transferred onto PVDF membranes using a semi‐dry transfer apparatus (Bio‐Rad, Milan, Italy). Non‐specific binding was blocked using 5% skimmed milk in TBS‐T (0.1% Tween‐20 in 1× Tris‐buffered saline, pH 7.4) for 2 h at room temperature. Membranes were then incubated with specific primary antibody solution at 4°C overnight with gentle constant shaking. After three thorough TBS‐S washes, the membranes were incubated with corresponding HRP‐conjugated second antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using Clear ECL (Bio‐Rad) and autoradiography.

Lysosomal electrophysiology

Lysosomal electrophysiology was performed in isolated enlarged lysosomes using a modified patch‐clamp method as described previously (Dong et al. 2008). Briefly, cells were treated for > 2 h with 1 μm vacuolin‐1, a lipophilic polycyclic triazine that can selectively increase the size of endosomes and lysosomes (Huynh & Andrews, 2005). Large vacuoles were observed in most vacuolin‐1‐treated cells. Enlarged vacuoles were also seen in some untreated P2X4‐expressing cells and no obvious difference in P2X4 channel properties was detected between enlarged vacuoles obtained with or without vacuolin‐1 treatment. Whole‐lysosome recordings were performed on manually isolated enlarged lysosomes (Dong et al. 2010). In brief, a patch pipette was pressed against a cell and quickly pulled away to slice the cell membrane. This allowed enlarged lysosomes to be released into the recording chamber and identified by monitoring enhanced green fluorescent protein fluorescence. After formation of a gigaseal between the patch pipette and an enlarged lysosome, capacitance transients were compensated. Voltage steps of several hundred millivolts with millisecond duration(s) were then applied to break the patched membrane and establish the whole‐lysosome configuration.

Unless otherwise stated, bath (cytoplasmic) solution contained 140 mm potassium gluconate, 4 mm NaCl, 1 mm EGTA, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.39 mm CaCl2 and 20 mm Hepes (pH was adjusted with KOH to 7.2; free [Ca2+] was 100 nm). The pipette (luminal) solution was a standard extracellular solution (modified Tyrode's: 145 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm Hepes, 10 mm glucose; the pH was adjusted with HCl or NaOH to 4.6 or 7.4). Data were collected using an Axopatch 2A patch‐clamp amplifier, Digidata 1440 and pClamp 10.2 software (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). Whole‐lysosome currents, elicited by voltage ramps from –140 to +140 mV and repeated at 4 s intervals, were digitized at 10 kHz and filtered at 2 kHz. All experiments were conducted at room temperature (21–23°C), and all recordings were analysed with pClamp 10.2 and Origin 8.0 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

Data analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made using ANOVA and Student's t test. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

V‐ATPase‐dependent ATP transport across lysosomal membranes by SLC17A9

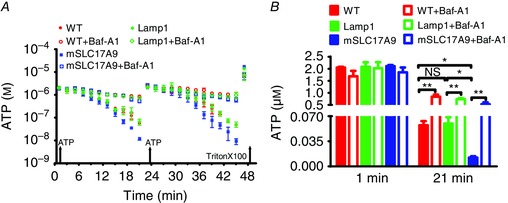

To investigate whether V‐ATPase is required for SLC17A9‐mediated lysosomal ATP transport, Baf‐A1 was adopted to inhibit V‐ATPase. ATP transport across the membranes of isolated lysosomes from Cos1 cells was measured using an ATP uptake assay as described (Cao et al. 2014; Huang et al. 2014). ATP transport was monitored by evaluating ATP concentrations in the buffer using a bioluminescent ATP assay (Haanes & Novak, 2010). Previously, we have demonstrated that bioluminescence loss is not caused by ATP hydrolysis but specifically by SLC17A9 transporting ATP into lysosomes (Cao et al. 2014). Therefore, a decrease of ATP concentration that is reflected by the disappearance of bioluminescence in the buffer suggested SLC17A9‐mediated ATP uptake by lysosomes. We compared luminescence decay over time following repeated addition of ATP (2 μm) to isolated lysosomes. As shown in Fig. 1 A, SLC17A9‐GFP but not Lamp1‐GFP expression facilitated lysosomal ATP uptake. This is consistent with our previous finding (Cao et al. 2014). Furthermore, we found that Baf‐A1 (400 nm) remarkably suppressed lysosome ATP uptake in both wild type cells and SLC17A9‐GFP‐expressing cells. For comparison, the concentration of ATP in the buffer at 21 min after the first ATP application was re‐plotted in Fig. 1 B. ATP concentrations in the buffer were significantly increased from 0.044 ± 0.006 to 0.997 ± 0.105 μm in wild type cells, and from 0.008 ± 0.001 to 0.403 ± 0.121 μm in SLC17A9‐GFP‐expressing cells at 21 min after the first ATP addition by Baf‐A1. This suggests that Baf‐A1 treatment decreases ATP transport in both wild type lysosomes and lysosomes expressing SLC17A9‐GFP.

Figure 1. ATP transport through SLC17A9 was blocked by Baf‐A1 .

A, ATP uptake in isolated lysosomes was blocked by V‐ATPase inhibitor Baf‐A1. Lysosomes isolated from wild type, rLamp1‐GFP or mSLC17A9‐GFP‐overexpressing Cos1 cells were subjected to ATP uptake assay in the presence of Baf‐A1 (400 nm). At 1 and 23 min, ATP was added to 100 μl of sample to a final concentration of 2 μm. Decay of ATP luminescence was detected over time as an indicator of active ATP uptake. At the end of the assay, 1% TritonX‐100 was added to measure total ATP released from vesicles. B, ATP levels at 1 and 21 min. Baf‐A1 inhibited ATP transport into lysosomes and resulted in higher extra‐lysosome ATP levels relative to controls. Data were obtained from three independent experiments. NS, not significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

V‐ATPase‐dependent ATP accumulation in lysosomes by SLC17A9

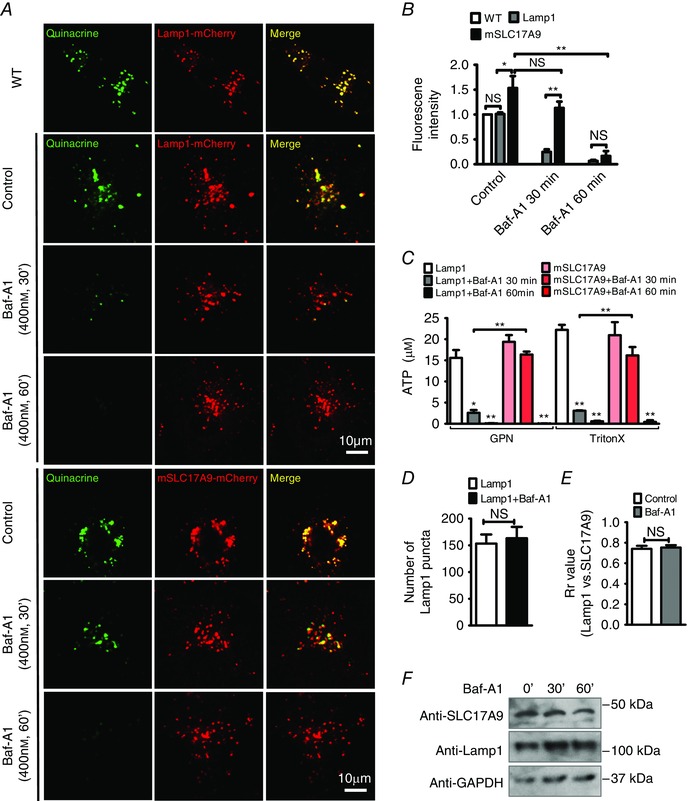

If V‐ATPase is required for lysosome ATP transport, Baf‐A1 treatment would eliminate ATP accumulation in lysosomes. To test this hypothesis, lysosomal ATP deposition was evaluated by the accumulation of quinacrine, a fluorescent dye used to locate intracellular ATP stores (Zhang et al. 2007; Dou et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2014). As shown in Fig. 2 A and B, Baf‐A1 treatment (400 nm) for 30 min was sufficient to eliminate quinacrine staining in Lamp1‐mCherry (control) but not in SLC17A9‐mCherry‐expressing cells. Quinacrine fluorescence intensity was decreased by 86.22 ± 4.42% in control cells, but only by 23.732 ± 9.63% in cells expressing SLC17A9‐mCherry with 30 min of Baf‐A1 treatment. However, treatment of Baf‐A1 for 60 min decreased quinacrine intensity by 86.264 ± 10.02% in cells expressing SLC17A9‐mCherry. These data suggest that overexpression of SLC17A9 increases ATP transport efficiency, which subsequently leads to the requirement of a longer Baf‐A1 treatment to deplete lysosomal ATP.

Figure 2. Baf‐A1 inhibited SLC17A9‐mediated lysosomal ATP accumulation .

A, Baf‐A1 inhibited lysosomal ATP accumulation through SLC17A9. Cos1 cells transiently overexpressing rLamp1‐mCherry or mSLC17A9‐mCherry were treated with 400 nm Baf‐A1 for 30 and 60 min. Quinacrine fluorescence was used to monitor ATP levels in lysosomes. Treatment with Baf‐A1 for 30 min significantly reduced ATP accumulation in lysosomes from Lamp1‐expressing but not SLC17A9‐expressing Cos1 cells. Treatment with Baf‐A1 for 60 min eliminated lysosomal ATP accumulation in both Lamp1‐ and SLC17A9‐expressing cells. WT, wild type. B, quinacrine fluorescence intensity quantification of images is shown in A. C, measurement of ATP levels in lysosomes isolated from Lamp1‐ or SLC17A9‐expressing Cos1 cells with or without Baf‐A1 treatment. Longer treatment with Baf‐A1 was required to suppress ATP accumulation in lysosomes expressing mSLC17A9‐mCherry. GPN (200 μm), a substrate of the lysosomal exopeptidase cathepsin C, was used to induce lysosome osmodialysis (Zhang et al. 2007) and specifically release lysosomal ATP. TritonX‐100 was used to release ATP from all membrane‐enclosed compartments. D, number of Lamp1‐positive puncta in cells with or without Baf‐A1 treatment. ImageJ software was used for data quantification. The quantity of Lamp1‐positive puncta was calculated based on the number of vesicles (dots) per cell. For each experiment, at least 50 cells were analysed. Experiments were repeated three times independently. E, co‐localization between SLC17A9‐mCherry and Lamp1‐GFP in Cos1 cells with or without Baf‐A1 treatment (400 nm, 60 min). At least 30 cells were analysed for each group. F, comparable Lamp1 and SLC17A9 protein levels in lysosomes isolated from Cos1 cells with or without Baf‐A1 (400 nm) treatment. The experiment was repeated three times in triplicate. NS, not significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

The role of V‐ATPase in lysosomal ATP accumulation was further evaluated by directly measuring ATP concentration in purified lysosomes. GPN (200 μm), a substrate of the lysosomal exopeptidase cathepsin C, was used to induce lysosome osmodialysis (Zhang et al. 2007) and specifically release lysosomal ATP. TritonX‐100 was used to release ATP from all membrane‐enclosed compartments. As shown in Fig. 2 C, pretreatment with Baf‐A1 (400 nm, 30 min) significantly decreased lysosomal ATP concentration from 14.66 ± 4.94 to 2.49 ± 0.90 μm in control cells expressing Lamp1‐mCherry but not in cells expressing SLC17A9‐mCherry (from 19.38 ± 1.60 to 16.37 ± 0.71 μm). However, pretreatment with Baf‐A1 for 60 min significantly reduced lysosomal ATP concentration in both control cells and cells expressing SLC17A9‐mCherry, by 99.2% (from 14.66 ± 4.94 to 0.11 ± 0.06 μm) and 99.6% (from 19.38 ± 1.60 to 0.04 ± 0.02 μm), respectively.

Because V‐ATPase is essential for lysosome trafficking and function, the disappearance of quinacrine staining and the decreased lysosomal ATP contents induced by Baf‐A1 could be due to a reduced number of lysosomes or SLC17A9 mistargeting. To exclude this possibility, Lamp1‐mCherry puncta of control cells (as shown in Fig. 2 A) were quantified before and after Baf‐A1 (60 min) treatment. Baf‐A1 did not significantly change the number of Lamp1‐positive puncta (Fig. 2 D), or the co‐localization between SLC17A9 and Lamp1 (Fig. 2 E). This suggests that Baf‐A1 did not alter lysosome number or SLC17A9 localization. This was further consolidated by the data showing a comparable level of SLC17A9 and Lamp1 proteins in the lysosomes isolated from Cos1 cells with or without Baf‐A1 treatment (Fig. 2 F, and see later Fig. 4 A for whole cell data). Together, these data suggest that V‐ATPase regulates ATP transport activity of SLC17A9 in lysosomes, subsequently leading to reduced lysosomal ATP accumulation.

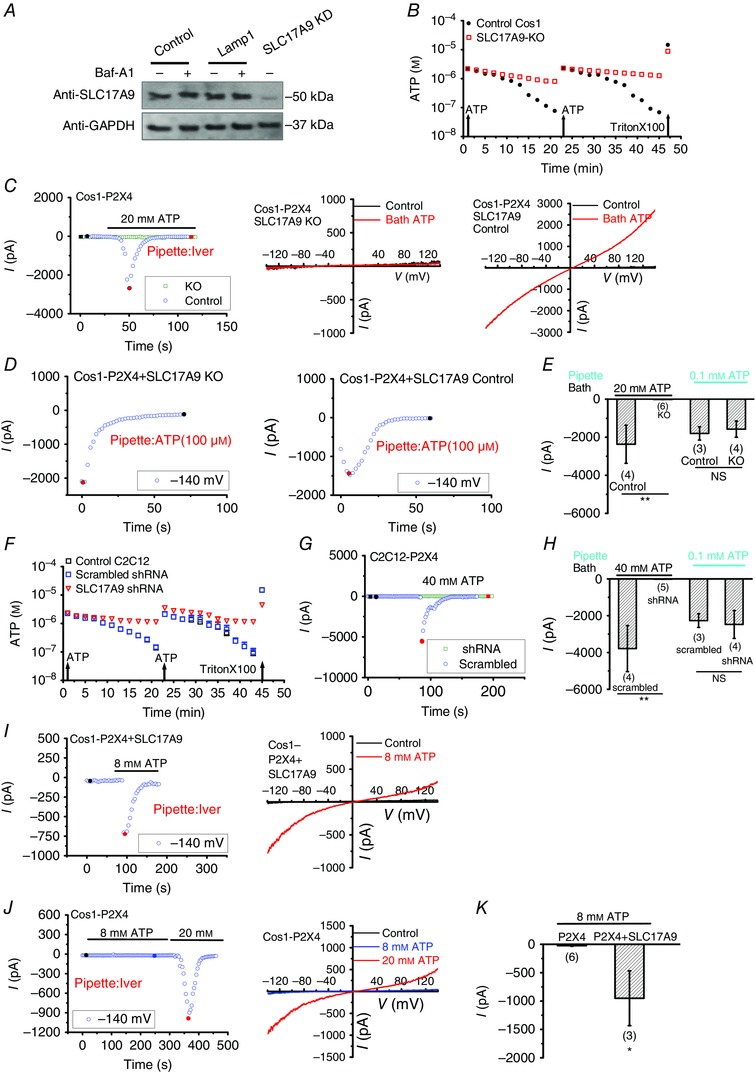

Figure 4. SLC17A9 is required for lysosomal P2X4 activation induced by cytosolic ATP .

A, representative Western blots showing knockdown of SLC17A9 by SLC17A9‐KO (CRISPR/Cas9) in Cos1 cells. Control cells were transfected with PX330‐GFP vector. Loading control was performed with an anti‐GAPDH antibody. Notably, Baf‐A1 treatment (400 nm, 60 min) did not significantly affect SLC17A9 expression. B, ATP uptake in lysosomes isolated from control or SLC17A9‐KO Cos1 cells. At 1 and 23 min, ATP was added to a 100 μl sample for a final concentration of 2 μm. Decay of ATP luminescence was detected over time as an indicator of active ATP uptake. At the end of the assay, 1% TritonX‐100 was added to measure the total ATP released from vesicles. The experiment was repeated three times independently. C and D, bath application of ATP (20 mm)‐mediated P2X4 activation was inhibited by CRISPR/Cas9 system‐mediated SLC17A9 knockout in the lysosome of Cos1 cells overexpressing P2X4 (C), whereas P2X4 activation induced by pipette infusion of 100 μm ATP was not affected (D). E, quantification of the peak P2X4 currents at −140 mV in conditions as described in C and D. F, ATP uptake in isolated lysosomes of control or SLC17A9 shRNA silencing C2C12 cells. At 1 and 23 min, ATP was added to 100 μl of sample to a final concentration of 2 μm. Decay of ATP luminescence was detected over time as an indicator of active ATP uptake. At the end of the assay, 1% TritonX‐100 was added to measure total ATP released from vesicles. Control cells were transfected with scramble shRNA. The experiment was repeated three times independently. G and H, bath application of ATP (40 mm)‐mediated P2X4 activation was inhibited by SLC17A9 shRNA in the lysosome of C2C12 cells overexpressing P2X4, whereas P2X4 activation induced by pipette infusion of 100 μm ATP was not affected. I, P2X4 currents induced by 8 mm bath ATP in Cos1 cells overexpressing both SLC17A9‐mCherry and P2X4‐GFP. J, P2X4 currents induced by 20 mm but not 8 mm bath ATP in Cos1 cells overexpressing P2X4‐GFP alone. K, statistical analysis showing that SLC17A9‐overexpression in Cos1 cells lowers the concentration of bath ATP required for P2X4 activation. The pipette solution contained 5 μm ivermectin. NS, not significant; **P < 0.01.

Activation of lysosomal P2X4 by ATP transported into lysosomes

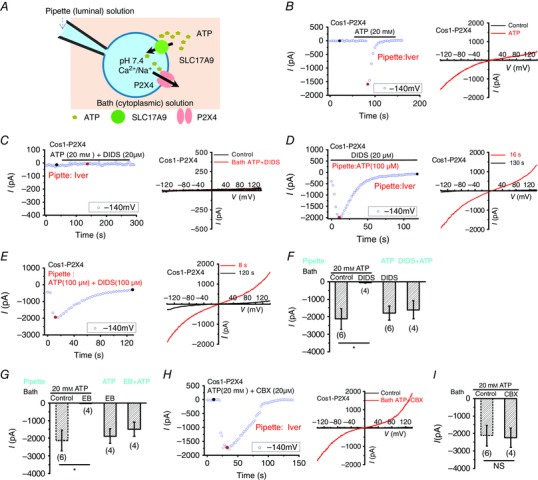

Previously, SLC17A9 was mainly studied by reconstituting purified transporter proteins into liposomes (Sawada et al. 2008; Miyaji et al. 2011; Omote et al. 2011) or using the purified lysosomes (Cao et al. 2014). The liposome is largely non‐physiological, and the crude lysosome isolation process may dissociate some components from lysosomal membranes. Both of these might lead to inaccurate results. To study ATP transport across lysosomal membranes under conditions that mimic the physiological environment, we have developed a new method. By recording enlarged lysosomes overexpressing P2X4‐GFP (Huang et al. 2014), we previously showed that P2X4 functions as a lysosomal channel activated by luminal ATP in a pH‐dependent manner. While the low pH at the luminal side inhibits P2X4 activity, increasing the luminal pH in the presence of ATP causes P2X4 activation. As ATP binds P2X4 from the luminal side of lysosomes (Huang et al. 2014), we suspected that ATP transport across lysosomal membranes would activate lysosomal P2X4 when luminal pH is clamped at 7.4 (Fig. 3 A). To facilitate P2X4 activation, ivermectin (Iver, 5 μm), a bacterium‐derived broad spectrum antiparasitic agent that specifically potentiates P2X4 (Priel & Silberberg, 2004; Huang et al. 2014), was included in pipettes. As shown in Fig. 3 B, when 20 mm ATP was applied to the bath (cytosolic side of the lysosome), large P2X4 currents were revealed in lysosomes isolated from Cos1 cells expressing P2X4‐GFP but not non‐transfected cells (data not shown). As the pipette (lumen of the lysosome) contained no ATP, the activation of P2X4 must be due to ATP transported into lysosomes.

Figure 3. Activation of lysosomal P2X4 by ATP transported into lysosome from the cytosol .

A, illustration of the whole‐lysosome recording of P2X4 currents in the cell overexpressing P2X4. Pipette (luminal) solution is a standard external solution (pH 7.4). The bath (cytosolic) solution is a high K+‐containing internal solution. SLC17A9 transports cytosolic ATP into lysosomes, leading to P2X4 activation. B, bath application of ATP (20 mm) activated P2X4 currents (with 5 μm ivemectin included in the pipette solution) in lysosomes expressing P2X4‐GFP. Left: whole‐lysosome currents were recorded under repeated voltage ramps (−140 to +140 mV; 400 ms). Current amplitudes measured at −140 mV were used to plot the time course of P2X4 activation. Note that P2X4 currents induced by bath ATP decrease with time due to desensitization. Right: representative I–V traces of whole‐lysosome currents before and after bath application of ATP at different time points (black and red circles). C–E, bath application of ATP‐mediated P2X4 activation was blocked by bath co‐application of 20 μm DIDS (C), whereas P2X4 activation induced by pipette infusion of 100 μm ATP was not affected by 20 μm DIDS either in the bath (D) or in the pipette (E). F, quantification of the peak P2X4 currents at −140 mV in conditions as described in C–E. G, quantification of the peak P2X4 currents at −140 mV indicating that P2X4 current induced by bath ATP was blocked by bath co‐application of 20 μm Evans Blue (EB), whereas P2X4 activation induced by pipette infusion of 100 μm ATP was not affected by EB either in the bath or in the pipette. H and I, P2X4 currents induced by bath ATP were not affected by co‐application of 20 μm CBX, an inhibitor of connexin and pannexin channels. Note, the same control was used for F, G and I. NS, not significant; *P < 0.05.

Previous studies showed that SLC17A9 was blocked by DIDS and Evans Blue, two widely used SLC17A9 inhibitors (Sawada et al. 2008; Cao et al. 2014), but not CBX, an inhibitor of connexin and pannexin channels (Dahl & Harris, 2008; Cao et al. 2014). Consistently, P2X4 currents induced by bath application of ATP were inhibited by 20 μm DIDS (Fig. 3 C and F) and 20 μm Evans Blue (Fig. 3 G). The inhibition of P2X4 current by bath co‐applying DIDS with ATP could be caused by a direct inhibition of P2X4 by DIDS. To exclude this possibility, 100 μm ATP was included in the pipette to directly activate P2X4 when DIDS was applied. DIDS (20 μm) did not inhibit luminal ATP‐induced P2X4 currents either from the cytoplasmic side (Fig. 3 D and F) or from the luminal side (Fig. 3 E and F). Likewise, Evans Blue (20 μm) did not inhibit P2X4 either from the cytoplasmic side or from the luminal side (Fig. 3 G). In contrast, CBX (20 μm) did not inhibit large P2X4 currents induced by bath application of 20 mm ATP (Fig. 3 H and I). These data suggest that SLC17A9 is probably attributed to the activation of P2X4 by cytosolic ATP.

Activation of lysosomal P2X4 by cytosolic ATP required SLC17A9

Considering that DIDS and Evans Blue were also used as anion channel blockers, to avoid the potential unspecific effects upon DIDS or Evans Blue, we examined whether deleting SLC17A9 would inhibit the bath ATP‐induced P2X4 current. If SLC17A9 is required for lysosomal ATP transport and the subsequent P2X4 activation, loss of SLC17A9 would eliminate the ATP transport, and therefore the P2X4 current induced by bath application of ATP. To test this, the CRISPR/Cas9 system was employed to knock out SLC17A9 in Cos1 cells. Western blotting analysis suggested that SLC17A9 expression was disrupted in CRISPR‐knockout cells (Fig. 4 A). Some residual signal is probably due to the contribution of non‐transfected cells. As expected, loss of SLC17A9 eliminated the ATP transport activity in Cos1 cells (Fig. 4 B). Furthermore, large P2X4 currents were detected by bath application of 20 mm ATP in lysosomes isolated from control but not SLC17A9 knockout cells (Fig. 4 C and E), suggesting SLC17A9 knockout abolished P2X4 activation induced by bath application of ATP. Notably, this is not because SLC17A9 knockout disrupted P2X4 channel because luminal ATP‐induced P2X4 currents were not affected (Fig. 4 D and E).

In addition to Cos1 cells, the coupling between P2X4 and SLC17A9 was further studied in C2C12, a mouse myoblast cell line. We have shown that knockdown of endogenous SLC17A9 using shRNA in C2C12 cells eliminated lysosomal ATP transport (Cao et al. 2014 and Fig. 4 F). Here, we found that large P2X4 currents were detected by bath application of ATP in lysosomes isolated from control but not SLC17A9 knockdown cells (Fig. 4 G and H). Notably, luminal ATP‐induced P2X4 currents were not affected, suggesting the loss of P2X4 currents is not due to disruption of P2X4 channels (Fig. 4 H). Together, these data indicate that SLC17A9 is necessary for cytosolic ATP‐mediated lysosomal P2X4 activation. These data also suggest that the functional interaction between SLC17A9 and P2X4 might be common in a variety of cells.

On the other hand, we found that a lower concentration of bath ATP was required to activate P2X4 in SLC17A9‐expressing Cos1 cells compared to WT Cos1 cells (Fig. 4 I–K), suggesting that SLC17A9 expression facilitates lysosomal ATP transport. This is consistent with the data showing an increase in lysosomal ATP uptake (Fig. 1) and lysosomal ATP accumulation (Fig. 2) in Cos1 cells expressing SLC17A9 compared to the control cells (Cao et al. 2014).

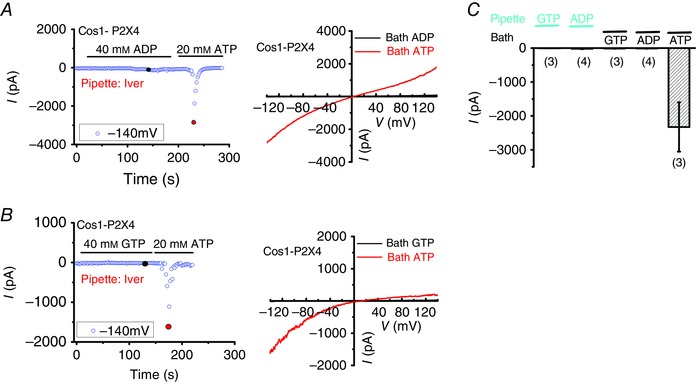

Bath application of SLC17A9‐permeable nucleotides other than ATP did not activate lysosomal P2X4

Previous study (Sawada, et al. 2008) suggested that, in addition to ATP, SLC17A9 transports other nucleotides, such as ADP, GTP and UTP. To corroborate the coupling between SLC17A9 and P2X4, we applied a high concentration of ADP or GTP in the bath. We found that bath application of ADP (40 mm) or GTP (40 mm) failed to induce P2X4 current on the lysosome. Moreover, no P2X4 current was detected by pipette infusion of 100 μm ADP or GTP (Fig. 5 C). Therefore, lysosomal P2X4 does not respond to ADP or GTP, as its plasma membrane counterpart does (Soto et al. 1996), although bath application of ATP (20 mm) induced significant P2X4 current in the same lysosomes (Fig. 5). These data strengthened the functional coupling between SLC17A9 and P2X4. Based on the data presented, we conclude that SLC17A9 transports cytoplasmic ATP into lysosomes to bind to and activate P2X4 from the luminal side.

Figure 5. ADP or GTP failed to activate lysosomal P2X4 .

A, bath application of ATP (20 mm) but not ADP (40 mm) induced P2X4 currents. Pipette solution contained ivermectin (5 μm), and its pH was adjusted to 7.4. B, bath application of ATP (20 mm) but not GTP (40 mm) induced P2X4 currents. C, quantification of the peak P2X4 currents at −140 mV in conditions as described in A and B. Also, pipette infusion of 100 μm ADP or GTP did not induce P2X4 currents in lysosomes isolated from Cos1 cells expressing P2X4‐GFP.

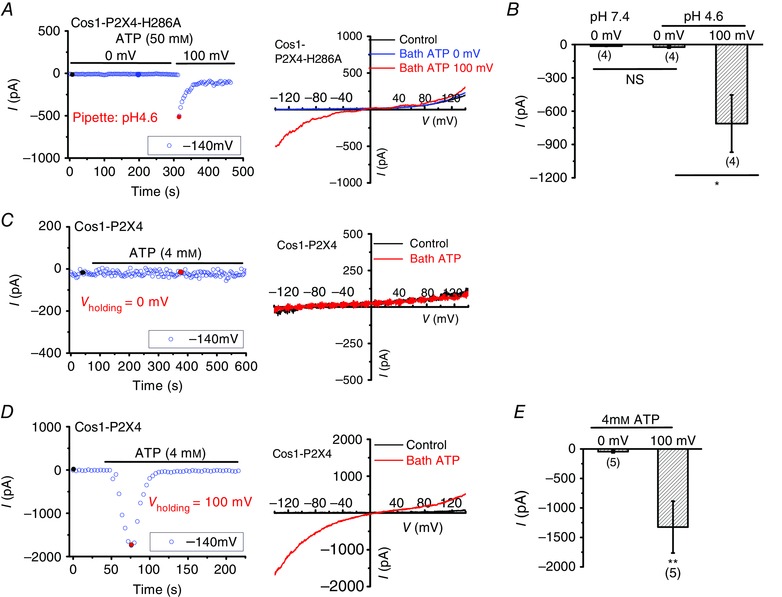

SLC17A9 transports ATP into lysosomes mainly using ΔΨ but not ΔpH as the driving force

Because P2X4 is suppressed by luminal low pH (Huang et al. 2014), to directly test whether pH gradient is required for lysosomal ATP transport, we employed a pH‐insensitive mutant P2X4‐H286A (Clarke et al. 2000) as the reporter. Because H286A shifts the dose‐dependent curve to the right, 50 mm ATP was applied to the bath. As shown in Fig. 6 A and B, 50 mm ATP did not induce significant P2X4‐H286A current when lysosomal pH was clamped at either 7.4 or 4.6 with ΔΨ held at 0 mV. These data suggest that ΔpH is not the primary driving force for ATP transport across the lysosome membrane. In contrast, significant P2X4‐H286A currents were revealed when ΔΨ was held at 100 mV (positive in the lumen of lysosome). These data suggest that lysosomal ATP transport is mainly driven by ΔΨ but not ΔpH across lysosomal membranes. To test whether a physiological concentration of ATP can be taken up into lysosomes by SLC17A9, 4 mm ATP (Beis & Newsholme, 1975; Schwiebert & Zsembery, 2003; Huang et al. 2010) was applied to lysosomes expressing P2X4‐GFP. Although no P2X4 current was detected when ΔΨ was clamped at 0 mV, significant P2X4 currents were observed when ΔΨ was held at 100 mV (Fig. 6 C–E). Together, these data suggest strongly that SLC17A9 mainly uses ΔΨ but not ΔpH to drive ATP transport into lysosomes. Our data also suggest a functional coupling between SLC17A9 and P2X4 in lysosomes.

Figure 6. ΔΨ but not ΔpH facilitated SLC17A9‐mediated ATP transport leading to lysosome P2X4 activation.

A, voltage‐dependent ATP transport into lysosomes activated lysosome P2X4. Whole‐lysosome recording of P2X4 currents in Cos1 cells overexpressing P2X4 H286A, a pH‐insensitive mutant. Pipette solution containing ivermectin (5 μm) was adjusted to pH 4.6. Bath treatment of 50 mm ATP could not induce P2X4 currents when ΔΨ was held at 0 mV, whereas significant P2X4 currents were revealed when ΔΨ was switched to 100 mV. B, quantification of the peak lysosomal P2X4 currents at −140 mV in conditions as indicated in A. Although increasing ΔpH did not cause P2X4‐H286A current in response to bath ATP (50 mm), elevating ΔΨ resulted in significant currents. C and D, activation of lysosome P2X4 by ATP transported into lysosomes when a physiological concentration of ATP was applied in the bath. Whole‐lysosome recording of P2X4 currents in Cos1 cells overexpressing P2X4. The pipette solution was adjusted to pH 7.4. Bath treatment of 4 mm ATP induced P2X4 activation when ΔΨ was held at 100 mV (D) but did not at 0 mV (C). E, quantification of the peak lysosomal P2X4 currents at −140 mV in conditions as indicated in C and D. NS, not significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

In this study, we show that lysosomal ATP transport via SLC17A9 is blocked by the V‐ATPase inhibitor Baf‐A1, suggesting a requirement of H+ gradient for SLC17A9 activity. This is consistent with previously reported vesicular glutamate transporters and VNUT (Sawada et al. 2008; El Mestikawy et al. 2011; Miyaji et al. 2011; Omote et al. 2011), which transport glutamate and ATP into secretory vesicles. V‐ATPase generates both voltage and pH gradient across vesicle membranes. To differentiate the contribution of voltage gradient and pH gradient in neurotransmitter transport, previous studies generally reconstitute vesicular transporter proteins into liposomes and use ionophore to clamp vesicle pH or voltage (Sawada et al. 2008). Although this method represents an effective and convenient way to study the biophysical properties of the purified transporters, the non‐native environment of artificial liposomes and the application of ionophores may cause inaccuracy in the results. Previously, lysosomal ATP transport was measured by monitoring luminescence decay over time following the addition of ATP to isolated lysosomes (Cao et al. 2014). However, the harsh lysosome isolation process and the very low ATP (micromolar level) employed make the lysosomal ATP transport assay largely non‐physiological. Moreover, the luminescence‐based ATP transport assay does not allow the manipulation of voltage and pH gradient across lysosomal membranes. With the aid of the novel whole‐lysosome patch clamp technique (Dong et al. 2008), we show in this study an activation of lysosomal P2X4 in response to the application of cytosolic ATP. As cytosolic ATP cannot bind to the cytoplasmic domain of P2X4 (Chataigneau et al. 2013; Huang et al. 2014), the activation of lysosomal P2X4 must be due to an active ATP transport mechanism leading to the presence of ATP in the lumen of the lysosome. Therefore, we have established a new lysosomal ATP transport assay to monitor ATP transport across lysosomal membranes in real time using P2X4 as the measure of transport. This method allows for monitoring ATP transport under more physiological conditions, and thus provides a unique tool to study lysosomal ATP transport. Both membrane potential and luminal pH can be controlled under patch‐clamp recording, and therefore this assay provides a powerful tool to study the respective contributions of ΔΨ and ΔpH generated by V‐ATPase in lysosomal ATP accumulation. By using this method, we have shown that SLC17A9 mainly uses the voltage gradient but not the pH gradient generated by V‐ATPase to accumulate ATP in lysosomes. Our results are consistent with the results obtained in proteoliposomes containing SLC17A9 (Sawada et al. 2008). They are also in accordance with ATP transport into chromaffin granules (Bankston & Guidotti, 1996).

Vesicular transporters are a group of proteins that move specific substrates across vesicular membranes. They have been classified into three subfamilies. The SLC17 subfamily includes vesicular glutamate transporters, excitatory amino acid transporters, Na+‐dependent phosphate transporters and vesicular nucleotide transporters (SLC17A9/VNUT). The SLC18 subfamily comprises vesicular monoamine transporters and acetylcholine transporters. The SLC32 subfamily consists of inhibitory amino acid transporters, such as vesicular GABA and glycine transporters (Sawada et al. 2008; El Mestikawy et al. 2011; Miyaji et al. 2011; Omote et al. 2011). The V‐ATPase plays a critical role in regulating vesicular transport activity by generating the electrochemical gradient of H+. The different vesicular transporters depend differentially on the two components (ΔpH and Δψ ) of the H+ electrochemical gradient. SLC17 subfamily members rely more on Δψ than ΔpH to transport the negatively charged glutamate or ATP. In contrast, SLC18 subfamily members rely mainly on ΔpH to transport positively charged substrates (e.g. monoamines and acetylcholine). SLC32 proteins that transport neutral ions (e.g. GABA and glycine) depend equally on both ΔpH and ΔΨ. Therefore, lysosomal SLC17A9 functions in a similar manner to other SLC17 subfamily of transporters but distinct from SLC18 and SLC32 subclasses (Chaudhry et al. 2008; Van Liefferinge et al. 2013).

The physiological role of lysosomal ATP is currently uncertain. By using an in vitro cell free assay, it was reported that ATP directly activated proteases such as cathepsin D, one of the main hydrolases in lysosomes, and increased proteolysis within lysosomes (Pillai & Zull, 1985). We suspect that lysosomal ATP may be essential for cathepsin D activation within lysosomes, playing a physiological role in the regulation of proteolysis in lysosomes. Consistent with this notion, both SLC17A9 deficiency and cathepsin D deficiency result in lysosome dysfunction, lysosomal storage and cell death (Koike et al. 2000; Siintola et al. 2006; Steinfeld et al. 2006; Benes et al. 2008; Cao et al. 2014). Given that P2X4 opening results in lysosomal Ca2+ release and fusion (Huang et al. 2014), SLC17A9/ATP may modulate lysosomal Ca2+ homeostasis and fusion by regulating P2X4 activity. This awaits further investigation.

It has been well defined that SLC17A9 contributes to ATP storage on secretory vesicles, which plays an essential role in ATP exocytosis and subsequent activation of P2X/P2Y‐mediated purinergic responses in the plasma membrane (Tokunaga et al. 2010; El Mestikawy et al. 2011). However, the regulatory mechanism of vesicle exocytosis is unclear. In this study, we have shown strong evidence to suggest a functional coupling between SLC17A9 and P2X4 in lysosomal membranes. Given that P2X4 participates in the fusion between secretory granules and the plasma membrane (Miklavc et al. 2011), the functional coupling between SLC17A9 and P2X4 in lysosomal membranes suggests that SLC17A9 may regulate P2X4 by accumulating lysosomal ATP. Therefore, it controls granule exocytosis. In addition, recent studies suggest an involvement of SLC17A9 in vesicular ATP release in human epidermal keratinocytes (Inoue et al. 2014) and disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP) (Cui et al. 2014). Our study may also help to uncover the molecular mechanisms underlying vesicular ATP release in keratinocytes and the pathogenic mechanisms for DSAP, although further studies are needed to confirm the identity of the vesicles.

In summary, we have established a new method to study lysosomal ATP uptake. By using this method, together with the inhibition of lysosomal ATP uptake by Baf‐A1, we suggest that lysosomes take up ATP mainly using membrane potential gradient but not pH gradient generated by V‐ATPase across lysosomal membranes. SLC17A9‐mediated ATP accumulation in lysosomes leads to lysosomal P2X4 activation, suggesting a regulatory mechanism of lysosomal P2X4 by SLC17A9.

Additional information

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

X.Z.Z. performed electrophysiology experiments and data analysis. Q.C. performed ATP uptake, some Western blotting and confocal microscopy experiments and data analysis. X.S. performed some Western blotting and confocal microscopy experiments and data analysis. X.Z.Z. and X.P.D. designed the projects and wrote the manuscript with input from co‐authors.

Funding

This work was supported by start‐up funds to X.D. from the Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Dalhousie University, DMRF Equipment Grant, DMRF new investigator award, CIHR grant (MOP‐119349), CIHR New Investigator award (201109MSH‐261462‐208625), NSHRF Establishment Grant (MED‐PRO‐2011‐7485) and CFI Leaders Opportunity Fund‐Funding for research infrastructure (29291).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ruth Murrell‐Lagnado for P2X4 constructs. We appreciate the encouragement and helpful comments from other members of the Dong laboratory.

This is an Editor's Choice article from the 1 August 2016 issue.

References

- Bankston LA & Guidotti G (1996). Characterization of ATP transport into chromaffin granule ghosts. Synergy of ATP and serotonin accumulation in chromaffin granule ghosts. J Biol Chem 271, 17132–17138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beis I & Newsholme EA (1975). The contents of adenine nucleotides, phosphagens and some glycolytic intermediates in resting muscles from vertebrates and invertebrates. Biochem J 152, 23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes P, Vetvicka V & Fusek M (2008). Cathepsin D–many functions of one aspartic protease. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 68, 12–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Q, Zhao K, Zhong XZ, Zou Y, Yu H, Huang P, Xu TL & Dong XP (2014). SLC17A9 protein functions as a lysosomal ATP transporter and regulates cell viability. J Biol Chem 289, 23189–23199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chataigneau T, Lemoine D & Grutter T (2013). Exploring the ATP‐binding site of P2X receptors. Front Cell Neurosci 7, 273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry FA, Edwards RH & Fonnum F (2008). Vesicular neurotransmitter transporters as targets for endogenous and exogenous toxic substances. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 48, 277–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke CE, Benham CD, Bridges A, George AR & Meadows HJ (2000). Mutation of histidine 286 of the human P2X4 purinoceptor removes extracellular pH sensitivity. J Physiol 523, 697–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA & Zhang F (2013). Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Li L, Wang W, Shen J, Yue Z, Zheng X, Zuo X, Liang B, Gao M, Fan X, Yin X, Shen C, Yang C, Zhang C, Zhang X, Sheng Y, Gao J, Zhu Z, Lin D, Zhang A, Wang Z, Liu S, Sun L, Yang S, Cui Y & Zhang X (2014). Exome sequencing identifies SLC17A9 pathogenic gene in two Chinese pedigrees with disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. J Med Genet 51, 699–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl G, Harris AL (2008). Pannexins or connexins? In Connexins: A Guide, ed. Harris AL & Locke D, pp. 287–301. New York: Humana‐Springer.

- Dong XP, Cheng X, Mills E, Delling M, Wang F, Kurz T & Xu H (2008). The type IV mucolipidosis‐associated protein TRPML1 is an endolysosomal iron release channel. Nature 455, 992–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong XP, Shen D, Wang X, Dawson T, Li X, Zhang Q, Cheng X, Zhang Y, Weisman LS, Delling M & Xu H (2010). PI(3,5)P2 controls membrane trafficking by direct activation of mucolipin Ca2+ release channels in the endolysosome. Nat Commun 1, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Y, Wu HJ, Li HQ, Qin S, Wang YE, Li J, Lou HF, Chen Z, Li XM, Luo QM & Duan S (2012). Microglial migration mediated by ATP‐induced ATP release from lysosomes. Cell Res 22, 1022–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Mestikawy S, Wallen‐Mackenzie A, Fortin GM, Descarries L & Trudeau LE (2011). From glutamate co‐release to vesicular synergy: vesicular glutamate transporters. Nat Rev Neurosci 12, 204–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson R, Nordstrom KJ, Stephansson O, Hagglund MG & Schioth HB (2008). The solute carrier (SLC) complement of the human genome: phylogenetic classification reveals four major families. FEBS Lett 582, 3811–3816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haanes KA & Novak I (2010). ATP storage and uptake by isolated pancreatic zymogen granules. Biochem J 429, 303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hediger MA, Clemencon B, Burrier RE & Bruford EA (2013). The ABCs of membrane transporters in health and disease (SLC series): introduction. Mol Aspects Med 34, 95–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Zhang X, Li S, Liu N, Lian W, McDowell E, Zhou P, Zhao C, Guo H, Zhang C, Yang C, Wen G, Dong X, Lu L, Ma N, Dong W, Dou QP, Wang X & Liu J (2010). Physiological levels of ATP negatively regulate proteasome function. Cell Res 20, 1372–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Zou Y, Zhong XZ, Cao Q, Zhao K, Zhu MX, Murrell‐Lagnado R & Dong XP (2014). P2X4 forms functional ATP‐activated cation channels on lysosomal membranes regulated by luminal pH. J Biol Chem 289, 17658–17667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh C & Andrews NW (2005). The small chemical vacuolin‐1 alters the morphology of lysosomes without inhibiting Ca2+‐regulated exocytosis. EMBO Rep 6, 843–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Komatsu R, Imura Y, Fujishita K, Shibata K, Moriyama Y & Koizumi S (2014). Mechanism underlying ATP release in human epidermal keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 134, 1465–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike M, Nakanishi H, Saftig P, Ezaki J, Isahara K, Ohsawa Y, Schulz‐Schaeffer W, Watanabe T, Waguri S, Kametaka S, Shibata M, Yamamoto K, Kominami E, Peters C, von Figura K & Uchiyama Y (2000). Cathepsin D deficiency induces lysosomal storage with ceroid lipofuscin in mouse CNS neurons. J Neurosci 20, 6898–6906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklavc P, Mair N, Wittekindt OH, Haller T, Dietl P, Felder E, Timmler M & Frick M (2011). Fusion‐activated Ca2+ entry via vesicular P2X4 receptors promotes fusion pore opening and exocytotic content release in pneumocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 14503–14508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyaji T, Sawada K, Omote H & Moriyama Y (2011). Divalent cation transport by vesicular nucleotide transporter. J Biol Chem 286, 42881–42887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omote H, Miyaji T, Juge N & Moriyama Y (2011). Vesicular neurotransmitter transporter: bioenergetics and regulation of glutamate transport. Biochemistry 50, 5558–5565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai S & Zull JE (1985). Effects of ATP, vanadate, and molybdate on cathepsin D‐catalyzed proteolysis. J Biol Chem 260, 8384–8389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priel A & Silberberg SD (2004). Mechanism of ivermectin facilitation of human P2X4 receptor channels. J Gen Physiol 123, 281–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada K, Echigo N, Juge N, Miyaji T, Otsuka M, Omote H, Yamamoto A & Moriyama Y (2008). Identification of a vesicular nucleotide transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 5683–5686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwiebert EM & Zsembery A (2003). Extracellular ATP as a signaling molecule for epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1615, 7–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siintola E, Partanen S, Stromme P, Haapanen A, Haltia M, Maehlen J, Lehesjoki AE & Tyynela J (2006). Cathepsin D deficiency underlies congenital human neuronal ceroid‐lipofuscinosis. Brain 129, 1438–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto F, Garcia‐Guzman M, Gomez‐Hernandez JM, Hollmann M, Karschin C & Stuhmer W (1996). P2X4, an ATP‐activated ionotropic receptor cloned from rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93, 3684–3688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld R, Reinhardt K, Schreiber K, Hillebrand M, Kraetzner R, Bruck W, Saftig P & Gartner J (2006). Cathepsin D deficiency is associated with a human neurodegenerative disorder. Am J Hum Genet 78, 988–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga A, Tsukimoto M, Harada H, Moriyama Y & Kojima S (2010). Involvement of SLC17A9‐dependent vesicular exocytosis in the mechanism of ATP release during T cell activation. J Biol Chem 285, 17406–17416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Liefferinge J, Massie A, Portelli J, Di Giovanni G & Smolders I (2013). Are vesicular neurotransmitter transporters potential treatment targets for temporal lobe epilepsy? Front Cell Neurosci 7, 139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhang X, Dong XP, Samie M, Li X, Cheng X, Goschka A, Shen D, Zhou Y, Harlow J, Zhu MX, Clapham DE, Ren D & Xu H (2012). TPC proteins are phosphoinositide‐activated sodium‐selective ion channels in endosomes and lysosomes. Cell 151, 372–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Chen G, Zhou W, Song A, Xu T, Luo Q, Wang W, Gu XS & Duan S (2007). Regulated ATP release from astrocytes through lysosome exocytosis. Nat Cell Biol 9, 945–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]