Abstract

Context

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations of airflows coupled with physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling of respiratory tissue doses of airborne materials have traditionally used either steady-state inhalation or a sinusoidal approximation of the breathing cycle for airflow simulations despite their differences from normal breathing patterns.

Objective

Evaluate the impact of realistic breathing patterns, including sniffing, on predicted nasal tissue concentrations of a reactive vapor that targets the nose in rats as a case study.

Materials and methods

Whole-body plethysmography measurements from a free-breathing rat were used to produce profiles of normal breathing, sniffing, and combinations of both as flow inputs to CFD/PBPK simulations of acetaldehyde exposure.

Results

For the normal measured ventilation profile, modest reductions in time- and tissue depth-dependent areas under the curve (AUC) acetaldehyde concentrations were predicted in the wet squamous, respiratory, and transitional epithelium along the main airflow path, while corresponding increases were predicted in the olfactory epithelium, especially the most distal regions of the ethmoid turbinates, versus the idealized profile. The higher amplitude/frequency sniffing profile produced greater AUC increases over the idealized profile in the olfactory epithelium, especially in the posterior region.

Conclusions

The differences in tissue AUCs at known lesion-forming regions for acetaldehyde between normal and idealized profiles were minimal, suggesting that sinusoidal profiles may be used for this chemical and exposure concentration. However, depending upon the chemical, exposure system and concentration, and the time spent sniffing, the use of realistic breathing profiles—including sniffing—could become an important modulator for local tissue dose predictions.

I. Introduction

Advances in computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling of airflow through the mammalian respiratory tract have been driven by a need to better understand the pharmacokinetics of inhaled pharmaceuticals in addition to potential exposures to harmful chemicals, airborne pathogens, air pollution, and other airborne hazards. The ability to more accurately assess health impacts associated with these inhalants has relied on integrating imaging-based, anatomically correct three-dimensional (3D) CFD models with physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models of tissue physiology important to chemical absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination to form a comprehensive representation of the respiratory system across species. Such models are becoming increasingly realistic and meaningful due to recent advances in computational efficiency, 3D imaging and image segmentation, and metabolic parameters derived from in-vitro and in vivo experimental data (Appelman et al., 1982; Corley et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2013; Morgan and Monticello, 1990; Overton et al., 1987; Schroeter et al., 2014; Yin et al., 2013).

Despite the demonstrated impact of incorporating realistic anatomy, most CFD models continue to use either steady-state airflow (Corley et al., 2012; Luo and Liu, 2008; Schroeter et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2013) or idealized transient breathing patterns approximated by sinusoidal flow rates or inlet pressures (Corley et al., 2015; Ishikawa et al., 2009; Kabilan et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2013), even though natural breathing patterns are generally not sinusoidal. A free-breathing rat performs a range of inhalation maneuvers, from normal breathing—more specifically defined as easy, free respiration, as observed normally under resting conditions—to higher amplitude, higher frequency sniffs (Wachowiak, 2011). In this paper, we explore the effects of realistic breathing patterns—including sniffing—on airflow patterns and their impact on site-specific tissue uptake of a reactive, water-soluble vapor that targets the nose as a case study.

Our approach addresses the effects of two points: 1) realistic breathing waveforms versus the idealized sinusoid, and 2) realistic breathing patterns modeled by an admixture of normal breathing and sniffing. We investigate the effects of these breathing patterns using a previously published two-way coupled, time-dependent CFD-PBPK model for the uptake of acetaldehyde vapor in nasal tissues of the rat (Corley et al., 2015). Acetaldehyde was selected because it is less reactive than the other reactive aldehydes previously evaluated (formaldehyde and acrolein) and was, therefore, able to penetrate deeper into nasal tissues. Acetaldehyde is also an important industrial intermediate, occurs naturally in many foodstuffs, is a major constituent in cigarette smoke, and is a metabolic byproduct of ethanol and vinyl acetate exposures (Bogdanffy et al., 1999; Corley et al., 2015; Teeguarden et al., 2008). When inhaled, acetaldehyde can produce degenerative lesions in olfactory and respiratory epithelial tissues in the noses of rodents in subchronic inhalation studies at air concentrations >50 ppm and tumors in chronic studies at air concentrations >750 ppm (Teeguarden et al., 2008). This study compared simulated breathing profiles at a single air concentration of 50 ppm, corresponding to the no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) for nasal toxicity.

Breathing waveforms were measured by whole-body plethysmography in an unrestrained, unanaesthetized female Sprague-Dawley rat to obtain a representative normal breath and a representative sniff. We then combined these breath profiles to form five 60-second sequences to achieve a pseudo steady-state in breath-by-breath tissue concentrations: normal breathing, high-frequency (~8 Hz) exploratory sniffing, and three pseudorandom combinations of both. Resulting site-specific tissue doses of acetaldehyde were then compared with previous results of acetaldehyde uptake based on a 60-second sinusoidal (idealized) breathing profile (Corley et al., 2015).

II. Methods

A. Breathing Pattern Determination

All animal use followed protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Respiratory signals were acquired from several unanesthetized, unrestrained female Sprague-Dawley rats covering a broad range of ages and body weights on a separate project. A whole body plethysmograph (WBP; Buxco Research Systems, Wilmington, NC) was used to record the waveforms over 5-10 minutes, including periods of normal breathing and exploratory sniffing. The WBP signal recording from a single 314 gram rat was used for this study, because this animal was closest in body weight to the male Sprague-Dawley rat from which the nasal airway anatomy was previously extracted from μCT scans for modeling (see below) and to eliminate inter-animal variability that could confound comparisons of representative normal and sniffing profiles.

Plethysmography data were read using the bioread plugin for Python (https://pypi.python.org/pypi/bioread/0.9.3). Each breath—including full inhalation and exhalation—was labeled by determining the zero crossings, i.e. the points at which the flow reversed from inhale to exhale or vice versa. Breaths were then clustered by a two-dimensional k-means algorithm (Lloyd, 1982) weighted by Euclidean distance based on signal frequency and breath symmetry. Breath symmetry (S) was defined as the normalized ratio between inhale and exhale durations:

thus evaluating to 1 when inhale period is infinitely greater than exhale period, −1 in the opposite case, and 0 when the two periods are equal. Frequency was mapped to an interval [−1, 1] ensuring equal limits in each dimension of the clustering plane. That is, by mapping both frequency and symmetry to the same range, each was given equal weight. The k-means algorithm was then used to define three groups: normal breaths, exploratory sniffs, and intermediate breaths.

A representative sniff was constructed from the exploratory sniff group by first calculating the mean sniff period, then by normalizing the period of each individual sniff to the mean period. The representative, or “typical,” sniff was taken as the average of the normalized sniffs (see Figure 1A). Finally, the typical sniff was adjusted so that the inhaled volume matched the exhaled volume.

Figure 1.

(A) Shows a subset of sniffs used to determine a representative sniff. In (B), the average sniff is compared to two sinusoids: one matched by period, the other matched to the inhale portion of the sniff.

A similar procedure was followed to obtain a representative breath. However, after calculating a typical breath from the group of period-normalized breaths, it was noticed that the breath profile was attenuated due to averaging, particularly near the onset of the exhale cycle. The result was that a feature observed in each sampled individual breath, characterized by a small dip in the flow rate immediately following the onset of exhalation, was lost in the average composite because of variations in inhale durations. To account for this, each breath was split piecewise into inhalation and exhalation phases and the two phases were averaged separately. Figure 2A shows the effect of simply averaging the breaths, while Figure 2B illustrates the piecewise approach, with the final typical breath profile a more accurate representation of normal breathing. It should be noted that that the dip in the flow rate at approximately 0.2 seconds is more faithfully represented in Figure 2B than it is in 2A. The resultant breath was mapped to a period of 0.6 seconds to match that of the reference sine wave used in our previous simulations (Corley et al., 2015). Finally, the breath was offset to integrate to zero, and the inhale and exhale portions were volume-matched to a reference sine wave of the same period.

Figure 2.

(A) Depicts the initial method for determining a representative normal breath, wherein a signal feature, present in each individual breath, is lost at around 0.2 s in the representative breath. (B) Shows the revised method, wherein the portions of the trace above and below the zero axis were mapped to their respective mean intervals and averaged separately, preserving the signal component at t = ~0.2 s. Finally, (C) shows the representative breath mapped to a 0.6 s interval compared to two sinusoidal approximations: a period-matched sinusoid (red), which we have used in past simulations, and an inhale-matched sinusoid, fitted to the above-x-axis portion of the representative breath. (C) Highlights the compromises assumed by employing a representative sinewave.

To generate flow sequences for use in CFD simulations, six 60 second breathing profiles—the time required to reach breath-by-breath steady state tissue concentration profiles in Corley et al. (2015)—were generated: one represented by the reference sinewave (Figure 3A), one comprised of normal breaths (Figure 3B), one comprised of sniffs (Figure 3C), and three comprised of combinations of sniffs and normal breaths (Figure 3, D-F). For the combination profiles, we emulated the clustering of breaths and sniffs observed in vivo (see Figure 4) with a function designed in Python to pseudo-randomly assemble groups of breaths and sniffs. The combination profiles were constrained to contain equal parts by time sniffing and normal breathing as we are unaware of any data that reports actual percentages of time spent sniffing vs. normal breathing under conditions used in inhalation toxicology studies.

Figure 3.

Each plot shows a 60-s breathing profile used as input in a simulation. (A) Shows a sinusoidal approximation to flow, (B) shows flow derived from the representative breath, (C) shows flow derived from the representative sniff and (D–F) show variations of 50% by time breathing and sniffing, derived from the representative breath and sniff, respectively.

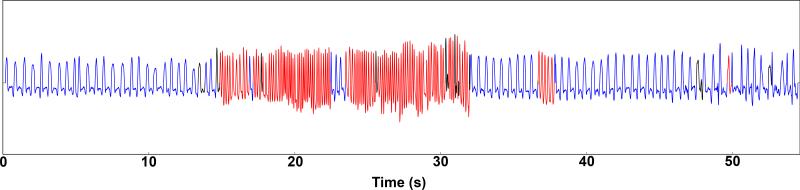

Figure 4.

The above shows a portion of the breathing signal captured by the plethysmograph. Each individual breath has been annotated to distinguish normal breaths (blue), sniffs (red) and uncategorized (black).

B. Model Generation

Image acquisition

The nasal airway geometry used for CFD modeling was based on a 326 g male Sprague-Dawley rat. The upper airways, extending from the nares to the upper trachea, were imaged using an x-ray microCT scanner (GE eXplore CT120) with the following settings: 90 kVp, 40 mA, 16 ms exposure time, and 900 projections over a full 360 degree gantry rotation. Images were reconstructed to 50 micron isotropic resolution.

Image segmentation

To extract the 3D geometry from the x-ray CT data, images were segmented as described in Corley et al. (2012). In short, background normalization and hybrid median filters were applied to the images to improve signal to noise ratio. Airways were then identified by semi-automated connected threshold in the image processing utility, Fiji (http://fiji.sc/Fiji) (Schneider et al., 2012), followed by manual validation and repair, resulting in a binary overlay for each dataset.

Generation of annotated surface mesh

A variant of the Marching Cubes algorithm (Lorensen and Cline, 1987) was then used to extract a triangulated surface mesh from the segmented data set. Volume-conserving smoothing (Kuprat et al., 2001) was employed to smooth surface normals. To prescribe compartment-specific parameters and to compare regional differences in uptake, anatomical regions of interest were differentiated using the commercial surface editing software MAGICS (http://software.materialise.com/magics) following nasal epithelial cell maps outlined in Corley et al. (2012) and Schroeter et al. (2008). The upper respiratory tract model used to compare breathing profiles was split into dry- and wet-squamous, transitional, respiratory, olfactory, and pharynx compartments (see Figure 5). The full respiratory airway model and how it was partitioned into tissue compartments that included the larynx, trachea, and pulmonary airways used to re-calibrate metabolism rates and evaluate performance against nasal extraction data is the same as described previously in Corley et al. (2015).

Figure 5.

The rat sinus annotated to reflect its six constituent compartments: the wet squamous, dry squamous, anterior respiratory/transitional, respiratory, olfactory and pharynx.

Volume mesh generation

An initial tetrahedral mesh was generated from the annotated surface mesh by following the approach detailed in Corley et al. (2012) and Kuprat and Einstein (2009). Annotations of the surface triangles of the tetrahedral mesh were inherited from the coincident triangles of the annotated triangular surface mesh or from the nearest triangles of the surface mesh in the case where surface triangulation of volume mesh had to be altered to ensure adequate volume mesh quality. Lastly, the tetrahedral volume mesh was converted into a surface-annotated polyhedral mesh using the polyDualMesh utility in OpenFOAM (OpenFOAM is an open source C++ computational continuum mechanics software and is a registered trademark of OpenCFD Ltd., Reading, UK; www.openfoam.com).

C. Simulations

Computational fluid dynamics

For detailed descriptions of airflow and acetaldehyde transport, refer to Corley et al. (2015). Briefly, the airflow prediction in our simulations were based on laminar, 3D, incompressible Navier-Stokes equations for fluid mass and momentum:

| Equation 1 |

| Equation 2 |

where ρ is the density, ν is the kinematic viscosity, u is the fluid velocity vector, and p is the pressure. Acetaldehyde transport was governed using the time-dependent convection-diffusion equation:

| Equation 3 |

where Cair and Dair are the concentration and diffusivity in the rat airway lumen, and u is the fluid velocity vector from Eqs. 1-2.

Air was considered the working fluid for the simulations with a density of 1.0 kg/m3 and a kinematic viscosity of 1.502×10−5 m2/s. The model does not currently account for gain or loss of heat or humidity, as the inhaled air mixes and equilibrates with residual air during the full breathing cycle. The flow rates for the sinusoidal breathing, normal breathing, sniffing, and mixed breathing were specified at the inlet for each simulation and the code adjusted the velocity to match the specified flow rate at every time step. A zero-pressure boundary condition was assumed for the outlet. A no-slip wall condition was applied to the airway wall boundaries, which were assumed to be rigid and impermeable.

Physiologically-based pharmacokinetics

We incorporated the PBPK model of Teeguarden et al. (2008), with some modifications based upon differences in anatomy in our initial CFD/PBPK model for acetaldehyde (Corley et al., 2015). The basic structure of the current CFD/PBPK is the same with the exception of separating the mucus layer from the original mucus+epithelial compartment. The mucus layer thickness was assumed to be 10 μm based on Schroeter et al. (2014); hence, the thickness of the epithelium in the three-compartment model was reduced by 10 μm accordingly. As described in Corley et al. (2015), uptake and off gassing of acetaldehyde was driven by airflow rates, exposure concentrations, partitioning, diffusion rates, tissue thickness, metabolism rates and location, and blood perfusion in the PBPK model airway boundary for each region or cell type, with the exception of the dry squamous epithelium in the nostrils where a simple mass-transfer coefficient was used.

A number of studies have been conducted to measure the metabolism of acetaldehyde in nasal tissue explants, homogenates, and cytosols from multiple species including rats (Bogdanffy et al., 1998; Casanova-Schmitz et al., 1984; Morris, 1997; Morris and Blanchard, 1992). The results from the in vitro studies have been scaled to in vivo, whole nose metabolic rates based upon nasal tissue wet weight, protein concentrations, and nasal cellular epithelial volumes which accounted for enzyme location (Bogdanffy et al., 1998, 1986; Plowchalk et al., 1997). Teeguarden et al. (2008) described these studies in the derivation of their rate constants for ALDH1 (a high capacity, low affinity pathway) and ALDH2 (a low capacity, high affinity pathway with human polymorphisms) and how these rates were re-calibrated against the nasal extraction data of Morris and Blanchard (1992) to account for the distribution of enzymes and tissue compartment volumes used in their rat PBPK model.

Since we adopted the PBPK model of Teeguarden et al. (2008) for our PBPK boundary condition, we recalibrated the metabolic rate constants for ALDH1 and ALDH2 due to differences in model structure (no mass-transfer coefficient was used except for the nasal vestibule, different tissue volumes based upon 3D CT imaging, and altered blood flows to nasal tissues due to acetaldehyde-induced vasodilation) against the steady-state inhalation nasal extraction data of Morris and Blanchard (Morris and Blanchard, 1992). In this study, we expanded the range of available data used to calibrate metabolism to all of the steady-state flow rates reported by Morris and Blanchard rather than just the single flow rate (300 ml/min) used in our prior CFD/PBPK model (Corley et al., 2015). The performance of the revised model was then evaluated against the cyclic breathing data of Morris and Blanchard (1992) that was not used for recalibration. All other physiological and acetaldehyde-specific PBPK parameters were the same as those reported previously in Corley et al. (2015).

D. Post-processing

Compartment averages

Whole-compartment concentration averages were recorded throughout the simulation for each tissue layer—mucus, epithelium, and subepithelium—used in the PBPK model. For analysis, concentrations for each compartment and tissue layer were taken as the average of the last 5 seconds of simulation time, thus approximating the breath-by-breath steady-state component of each concentration profile. Percent changes in concentration were calculated as differences between the sinusoidal simulation and the realistic breath, sniff, and mixed simulations, respectively.

Flux at peak inhalation

Predicted flux into the tissue at peak inhalation for each surface facet was recorded during the final inhalation period of the 60 second simulation. The time of peak inhalation was determined by extracting the time of the maximum flow value from the input flow profile during the last breath.

Time-depth AUC

For each surface facet, a time-depth integral, or area under the curve (AUC), of acetaldehyde concentration in the tissue was calculated to account for cumulative inhalant exposure over a single breath and through the tissue layers of the PBPK model, as introduced in Corley et al. (2015). The value stored for each surface facet represents the net accumulation of inhalant over the course of a breath summed over the tissue volume associated with the facet (i.e., through the epithelium and subepithelium).

Because the sniff period was shorter than that of the breaths, we divided the time-depth AUCs by their respective breath durations. This normalized the dose metric, allowing time-independent comparisons among breathing modalities. Following normalization, differences in time-depth AUC dose between normal breathing and sniffing and sinusoidal breathing were mapped to each facet in the geometry for visualization. Similarly, the percent change from sinusoidal breathing was calculated for the sniffing and normal breathing simulations. Three-dimensional plots were generated in Tecplot 360 (Tecplot. ©2015 Tecplot, Inc.) to visualize results by mapping facet values to the 3D geometry.

III. Results

Calibration of acetaldehyde metabolism rates

Steady-state inhalation nasal extraction data of Morris and Blanchard (1992) at 50, 100, 200, and 300 ml/min airflow rates and exposure concentrations of 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ppm were used to re-calibrate metabolism rates for ALDH1 and ALDH2 enzymes. As with the prior two-compartment PBPK airway boundary condition, the resulting CFD/PBPK simulations (Figure 6) were sensitive to parameter estimates for the minor, low-capacity/high-affinity ALDH2 pathway at the lowest concentrations (primarily 1 ppm and, to a lesser extent, 10 ppm) while the major high-capacity/low-affinity ALDH1 pathway accounted for most of the nasal metabolism at higher concentrations. With the inclusion of all steady-state inhalation flow rate data reported by Morris and Blanchard (1992), the only rate constant that required adjustment from the previous Corley et al. (2015) CFD/PBPK model was the Km for ALDH2 (Km2), which was reduced from 4.41 × 10−03 to 1.32 × 10−03 kg/m3/s, a factor of 3.1. All other chemical-specific model parameters remained unchanged from the previous model by Corley et al. (2015). The cyclic breathing data reported by Morris and Blanchard were then used to evaluate CFD/PBPK model's performance. Overall, the revised CFD/PBPK model provided a reasonable description of the cyclic breathing data with no further adjustments to any model parameter other than the use of an idealized sine-wave form corresponding to the rodent respirator operated at 100 ml/min minute stroke volume imposed over a 7 ml/min unidirectional flow for gas chromatography analysis as described in Morris and Blanchard to drive the simulations (Figure 6). Under transient breathing simulations, the ALDH2 pathway became more important to nasal tissue extraction than comparable steady-state simulations due to lower tissue concentrations.

Figure 6.

Comparisons of CFD/PBPK modelpredicted nasal extraction efficiencies with experimental data from rats reported by Morris & Blanchard (1992). Solid bars are used to represent experimental data (means ± s.d.) while hashed bars of the same color are used to represent CFD/PBPK simulations. Steady-state inhalation data at inspiratory flow rates of 50 (black), 100 (dark blue), 200 (red) and 300 (green) ml/min, each at an acetaldehyde exposure concentration of 1, 10, 100 and 1000 ppm were used to recalibrate metabolic rate constants for the ALDH1 and ALDH2 pathways. Nasal extraction efficiencies under cyclic breathing at 100 ml/min (light blue) were used to evaluate model performance under transient breathing conditions. Block arrows below the bar chart depict exposure concentrations where each aldehyde dehydrogenase enzyme dominated metabolism under steady-state inhalation conditions.

Compartment averages

Figure 7 shows average epithelial and subepithelial compartment concentrations for sinusoidal (A1-2) and normal breathing (B1-2) patterns over the 60 second simulation. Concentrations in the transitional and respiratory compartments decreased by 20% and 10%, respectively, when comparing normal breathing to sinusoidal breathing for both tissue layers. In the wet squamous, normal breathing resulted in a 12% concentration decrease in both tissue layers. Conversely, normal breathing effected an increase in concentration in the olfactory compartment over sinusoidal breathing by 11% in the epithelium and 15% in the subepithelium.

Figure 7.

Plots of average compartment concentration in the epithelium (top) and subepithelium (bottom) over the course of the simulation for each of the breathing modes (from left to right, sinusoidal approximation, breathing, sniffing and a mix of breathing and sniffing).

Figure 7C shows compartment concentrations for the all-sniff simulation, which reveals an increase above the sinusoid in the olfactory compartment of 95% and 145% in the epithelium and subepithelium, respectively. For the wet squamous, transitional, and respiratory compartment, the concentration in both tissue layers increased by 8%, 4%, and 24%, respectively.

Finally, mixed breathing profiles of normal breathing and sniffing are shown in Figure 7D. Mixed breathing generally resulted in uptake values between those of normal breathing and sniffing. Compared to sinusoidal breathing, mixed breathing resulted in a decrease in tissue concentration by 3% and 7% for the transitional compartment, an increase of 6% and 11% in the respiratory compartment, and increases of 57% and 70% in the olfactory compartment for the epithelium and subepithelium tissue layers, respectively. Concentration in the wet squamous in both tissue layers differed by less than 2%.

Flux at peak inhalation

Flux into the tissue was calculated at peak inhalation during the final breath of the simulation for each breathing mode. With the sinusoidal profile as the input, the nasal tissue experiences the lowest flux levels, peaking at 5.0×10−7 kg/m2s. Peak flux during normal breathing reaches 6.5×10−7 kg/m2s. Flux during sniffing exceeds that of the other modes, reaching levels as high as 1.2×10−6 kg/m2s. In the mixed breathing cases, flux levels closely matched those of normal breathing when the final inhale was during a breath and those of sniffing when the final inhale was during a sniff.

Time-depth AUC

Figure 8A, left, depicts airway surface difference maps in time-depth AUC concentrations between a normal breath and a single period of the sinusoidal flow approximation as reference, both normalized to per unit time. The largest differences occur as decreases in the transitional and respiratory compartments. Relatively smaller increases occur in the olfactory compartment.

Figure 8.

(A) shows differences in time-normalized AUC flux between normal breathing and the sinusoidal approximation (left) as well as the difference between sniffing and the sinusoidal approximation (right). On the bottom, (B) shows fractional change between normal breathing and sinusoid (left) and sniffing and sinusoid (right).

Figure 8B, left, is a surface map of fractional change between normal and reference sinusoidal breathing. Changes along the main flow path—across the wet squamous, transitional, and respiratory compartments—amount to decreases of 20-30%, with a subregion of the respiratory compartment approaching 40%. In the olfactory compartment, particularly in the most distal regions of the olfactory ethmoid turbinate, percent change ranged from a 30-60% increase, with a few clusters of facets as high as 80%.

Figure 8A, right, shows differences in time-depth AUC concentration between a sniff and a single period of sinusoidal breathing as reference, both normalized to per unit time. In this case, the largest predicted differences occur as increases in the olfactory compartment. Differences decrease in magnitude from the olfactory region along the dorsal portion of the sinus, from olfactory, to respiratory, to transitional, to wet squamous compartments. Finally, the anterior regions of the nose exhibited increases in predicted acetaldehyde concentrations in the respiratory, transitional, and wet squamous compartments. Regions of least difference were predicted along the main airflow path.

The surface map of fractional changes in time-normalized, time-depth AUC concentrations of sniffing from reference sinusoidal breathing (Figure 8B, right) demonstrates up to 500% increases in the olfactory compartment, with the majority increasing by 100-300%. Outside the olfactory tissues, percent changes are lower, with the dorsal portion of the nasal ridgeline increasing by between 10 and 30%, and the ventral areas of the transition and respiratory compartments increasing by between 20 and 40%. Along the main flow path, the majority of facets exhibit near-zero difference, with regions bordering the main flow increasing by up to 10%.

IV. Discussion

CFD/PBPK simulations suggest that normal breathing—as opposed to the sinusoidal approximation–results in perceptible changes to the patterns of acetaldehyde concentration in nasal tissues, but uptake varies inconsequentially in known lesion-forming regions: the anterior respiratory/transitional epithelium and anterior olfactory epithelium at this particular NOAEL exposure concentration (Dorman et al., 2008, p. 200). Sniffing profiles induced minor increases in acetaldehyde in the majority of the nasal tissues while producing notable increases in the olfactory compartment, including the lesion-forming regions.

Toxicological implications

While differences were observed in average compartment concentration, variation in compartment-wide averages does not guarantee variation in impactful dose metrics (Corley et al., 2015). Whole-compartment averages convey a coarse approximation of dose—restricted to gross anatomical compartments—but the model resolution enables finer spatial interpretation of results.

One such metric for assessing spatially-fine dosimetry significance is flux into the tissue at peak inhalation. Facet-by-facet comparisons across the model allow for assessment of site-specific differences, offering finer discretization over whole-compartment averages. Due to the magnitude differences in flow at peak inspiration, the differences among simulations were expected: flux into the tissue increased as peak flow increased from idealized breathing, to normal breathing, to sniffing. Moreover, differences among simulations were noticed only along the main flow path. This illustrates a potential shortcoming of instantaneous flux as a dose metric in that flow dynamics are the only significant governing factor; metabolism in the tissue and other PBPK parameters played a minimal role in mediating flux in these specific simulations (Corley et al., 2015). Thus, while differences in tissue flux exist, the variation among simulations for a chemical like acetaldehyde is not informative as they are reflective only of the changes in imposed flow dynamics.

The dose metric suggested in Corley et al. (2015) uses a time-depth integration of acetaldehyde concentration in the tissue over the course of a single breath. This approach accounts for the cumulative effect of inhalant exposure as well as its penetration into the tissue to calculate total tissue dose over a full breath once breath-by-breath steady state tissue concentrations are achieved. This approach was correlated well with the locations of lesions due to acetaldehyde vapor exposure (Corley et al., 2015). Differences due to normal breathing, although present as evidenced by Figure 8A, did not substantially affect the regions of toxicological significance determined in Corley et al., as percent changes along the dorsal portion of the olfactory compartment anterior to the ethmoid turbinate were less than 10%.

Sniffing, on the other hand, modulated dose to the regions of interest by an increase of 10-30%. The location of the high-dose region also expanded distally, broadening the areas of olfactory epithelium exposed to higher concentrations of acetaldehyde (Figure 8A and 8B, right).

The mixed breathing simulations did not undergo time-depth AUC analysis because time-depth AUC values were calculated only for the last breath. The AUC for the last breath in the mixed breathing simulations would be either a sniff or a breath, depending on how the input was ordered. This would produce results similar to either a sniff or a breath and would not provide meaningful insight into the dose response of the mixed-breathing modes.

Although time-depth AUC analysis was not performed for the mixed breathing cases, considering that mixed breathing is a superposition of normal breathing and sniffing suggests that mixed breathing would result in dose levels between the dose levels of normal breathing or sniffing only, weighted by time spent in each state. This can be seen in Figure 7, where the mixed breathing cases oscillate between the plateaus of normal breathing and sniffing.

The mixed breathing simulations modeled equal parts by time breathing and sniffing. However, under our experimental conditions, and for the single rat used in this study, analysis of 485 seconds of plethysmograph data indicated that sniffing accounted for at least 34% of the time breathing, perhaps more (22% of the breaths could not be confidently classified). As to breathing behaviors during inhalation toxicology studies, we are unaware of any data that describes how much time rats spend sniffing. We expect sniffing to be highly variable and exposure- and environmental condition-dependent. It is also likely to be more important at the beginning of the exposure(s) until the animal acclimates. Regardless, the sniffing profiles alone are a useful quantitative tool for understanding olfaction as described below.

Implications in olfaction

Sniffing induced differences ranging from 100-500% in the ethmoid turbinate region lined with olfactory tissues in the posterior nasal airways (Figure 8B, right). The increase in olfactory tissue dose in this region during sniffing suggests that high-amplitude, high-frequency sniffing results in deeper penetration of the most distal regions of the nasal geometry, as evidenced in Figures 8A and 8B, right. While exposure in the olfactory tissue-lined ethmoid turbinate region still does not exceed toxicologically significant levels achieved in the most anterior olfactory tissues lining the dorsal meatus, the relative differences in concentrations in the ethmoid turbinate region confirm one of the physiological purposes of sniffing, which is to increase odorant exposure to olfactory sensory neurons in the olfactory epithelium (Courtiol et al., 2011a; Wachowiak, 2011).

Sniffing has been demonstrated to shape odor response in the olfactory system through variation in sniff frequency and amplitude (Carey and Wachowiak, 2011; Courtiol et al., 2011b), ultimately influencing deposition patterns of a given odorant to correspond to olfactory sensory neurons sensitive to the odorant (Wei et al., 2013). Additionally, the transient nature of sniffing plays an important role in modulating the excitability of neurons involved in olfaction (Inoue and Strowbridge, 2008). Oscillatory stimulation of olfactory sensory neurons due to sniffing drives synaptic activity, propagating neural signaling when amplitude is sufficient and frequency of sustained input matches that of sniffing (Courtiol et al., 2011b; Inoue and Strowbridge, 2008).

Specifically, Wachowiak et al. (2011) raises the importance of understanding airflow patterns in the nasal cavity during free breathing and the associated effects on odor response. In our simulations, inhalant exposure levels in the olfactory-lined ethmoid regions of the nose were found to be relatively low compared to the other regions discussed, but this region experienced the largest relative difference among breathing modes, demonstrating a high sensitivity to input flow variation in this area. The sensitivity of olfactory sensory neurons to trace amounts of odorants, both spatially and temporally, suggest that coupled CFD-PBPK models could be used to assess odorant dose levels to the olfactory system and the neurological signaling implications thereof in free-breathing animals.

Limitations in Current Simulations and Opportunities for Future Research

Restricted simulation domain

The simulation domain was restricted to include only the upper respiratory tract, although the recalibration of metabolic rates and evaluation of model performance against nasal extraction data of Morris and Blanchard (1992; Figure 4) utilized the full airway model of Corley et al. (2015). This simplification reduced the complexity of the simulations, thereby significantly decreasing simulation time. The decision to truncate the geometries was based on other factors. First, the adverse effect due to acetaldehyde exposure—lesion formation—has been demonstrated experimentally to occur primarily in the upper respiratory tract (Dorman et al., 2008). Regions distal to the nasal pharynx, while potentially interesting, were not evaluated in this study. Second, since the simulations were performed on the same geometry, assumptions tied to the restricted domain are consistent across cases.

Such assumptions did, however, contribute to simulation inaccuracies in absolute tissue concentrations. The CFD boundary conditions assume no acetaldehyde returns through the pharynx during exhalation. This assumption results in “clean” air re-entering the system from the distal end of the simulation geometry. Introducing air with zero acetaldehyde concentration induces a larger gradient between tissue concentration and lumen concentration than what would be experienced by the system if the true return concentration re-entered during exhalation. This concentration gradient contributes to a higher propensity for washout in the tissue.

The impact of this simplifying assumption was evaluated using the idealized breathing profile in the previously developed full airway model of Corley et al. (2015). For this profile, absolute tissue concentrations using the simplified airway geometry were 20-50% lower than concentrations achieved when a full respiratory model that returned acetaldehyde from lower airways to the nose during exhalation. However, each full airway simulation took considerably longer and used significantly more computational resources to perform. Thus, for the purpose of this paper, which was to compare the relative differences in localized tissue doses between idealized and realistic breathing waveforms, including sniffing, restricting the geometry to the nose and pharynx for each simulation was considered sufficient.

Breath variation

This work explored the imposition of representative breaths and sniffs as flow input. Based on nominal relative differences between sinusoidal breathing and normal breathing, as well as among normal breathing, sniffing, and mixed breathing, incorporating actual breathing patterns (as shown in Figure 4) would probably not provide further insight into toxicologically significant doses of acetaldehyde in anterior olfactory epithelial sites sensitive to tumor formation. However, secondary sites important to olfaction are indeed affected by sniffing due to increased penetration and residence time of acetaldehyde over a greater surface of olfactory epithelium.

Single rat

Our findings were based on the breathing patterns of one representative rat that underwent whole-body plethysmography in a separate project. The rat selected exhibited no obvious deviation in breathing behaviors from the other rats, and the body weight of this animal was the closest to that of the rat used to develop the initial CFD model. Since the goal of this study was to compare the impact of breathing profiles, all else being equal, using a single rat was considered appropriate. Moreover, only the average shape of the breathing profile was used while the frequency and minute volumes were set to match the reference sinewave, which was determined allometrically (scaled by body weight). This also enabled the use of a female rat's breathing profile in a model geometry derived from a male rat: we operated under the assumption that the relative shape of respiration in rats does not vary significantly between genders, but are unaware of any literature to support this. Thus, these profiles could be used for rats at other body weights, although studies with additional rats—especially if they can also be imaged to develop rat-specific models—would be beneficial to confirm these initial findings.

Single species

This work suggests that incorporating realistic breathing may be useful for certain simulations in other species, including humans, as we have demonstrated previously with realistic human smoking behaviors (Corley et al., 2015). Ultimately, the goal of these studies is to simulate in vivo behaviors that are supported by experimentation or observation. Since animal models are used as proxies for human exposures, additional evaluations of realistic breathing versus idealized profiles across age and species as well as types of exposures would be useful tools for improving extrapolations of results from animal studies to humans.

Single inhalant

This study explored only the transport and metabolism of acetaldehyde at a single exposure concentration in the rat nasal airways. Tissue dose levels and uptake patterns determined by this work are thus only applicable to this exposure and may not extrapolate well to other concentrations of acetaldehyde where shifts in metabolism can occur or to other inhaled materials. However, these results are meant to be illustrative of new computational approaches that can be applied to improve our understanding of respiratory tissue dosimetry as well as mechanisms of olfaction. In fact, the differences seen among breathing modes could occur to a similar or even greater extent for other vapor exposures or even aerosol deposition studies as local tissue doses would be expected to vary as flow dynamics are changed. Thus, the breathing profiles that are scalable by body weight, the code used to generate the breathing profiles, and the CFD models are available upon request.

V. Conclusions

We have shown that, when comparing normal breathing to the sinusoidal approximation, differences in predicted tissue concentrations did not significantly affect internal doses of acetaldehyde in regions of toxicological significance at a NOAEL concentration. Thus, past vapor dosimetry simulations reported in our previous paper (Corley et al., 2015) that assumed a sinusoid as flow input at a NOAEL acetaldehyde concentration are not invalidated. However, it is possible that more significant differences could occur in rats at higher concentrations that are associated with toxicity and tumor formation. Regardless, imposing a realistic breathing profile does affect local tissue doses in areas that do not necessarily drive the risk assessments for acetaldehyde. Therefore, for the highest accuracy in computational models involving these tissues, flow inputs would be improved using realistic breathing patterns.

For other applications involving olfaction in rats, sniffing affects both tissue doses and locations of acetaldehyde, especially in olfactory epithelium-lined ethmoid turbinates of the rat, in this specific case study. Thus, when simulating a free-breathing rat, imposing a realistic waveform that includes an admixture of normal breathing and sniffing could be a useful addition to the repertoire in CFD modeling of inhalation exposures and explorations of underlying mechanisms of olfaction.

Acknowledgements

All model development and simulations were conducted under a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL073598). All plethysmography data were obtained from a U.S. Department of Energy Laboratory Directed Research and Development project evaluating the impact of radiation on pulmonary physiology and tissue remodeling (DE-AC05-76RL01830). The authors are grateful to Dr. Jeff Schroeter of Applied Research Associates, North Carolina, for his refinements to mapping locations of each cell type in the rat nasal airways. All CFD simulations were performed in part, using the PNNL Institutional Computing (PIC) facilities at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Appelman LM, Woutersen RA, Feron VJ. Inhalation toxicity of acetaldehyde in rats. I. Acute and subacute studies. Toxicology. 1982;23:293–307. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(82)90068-3. doi:10.1016/0300-483X(82)90068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanffy MS, Randall HW, Morgan KT. Histochemical localization of aldehyde dehydrogenase in the respiratory tract of the Fischer-344 rat. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1986;82:560–567. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(86)90291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanffy MS, Sarangapani R, Kimbell JS, Frame SR, Plowchalk DR. Analysis of vinyl acetate metabolism in rat and human nasal tissues by an in vitro gas uptake technique. Toxicol. Sci. Off. J. Soc. Toxicol. 1998;46:235–246. doi: 10.1006/toxs.1998.2542. doi:10.1006/toxs.1998.2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanffy MS, Sarangapani R, Plowchalk DR, Jarabek A, Andersen ME. A biologically based risk assessment for vinyl acetate-induced cancer and noncancer inhalation toxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 1999;51:19–35. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/51.1.19. doi:10.1093/toxsci/51.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey RM, Wachowiak M. Effect of sniffing on the temporal structure of mitral/tufted cell output from the olfactory bulb. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2011;31:10615–10626. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1805-11.2011. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1805-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova-Schmitz M, David RM, Heck H. d'A. Oxidation of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde by NAD+-dependent dehydrogenases in rat nasal mucosal homogenates. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1984;33:1137–1142. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90526-4. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(84)90526-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corley RA, Kabilan S, Kuprat AP, Carson JP, Jacob RE, Minard KR, Teeguarden JG, Timchalk C, Pipavath S, Glenny R, Einstein DR. Comparative Risks of Aldehyde Constituents in Cigarette Smoke Using Transient Computational Fluid Dynamics/Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Models of the Rat and Human Respiratory Tracts. Toxicol. Sci. kfv071. 2015 doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv071. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfv071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corley RA, Kabilan S, Kuprat AP, Carson JP, Minard KR, Jacob RE, Timchalk C, Glenny R, Pipavath S, Cox T, Wallis CD, Larson RF, Fanucchi MV, Postlethwait EM, Einstein DR. Comparative Computational Modeling of Airflows and Vapor Dosimetry in the Respiratory Tracts of Rat, Monkey, and Human. Toxicol. Sci. 2012;128:500–516. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs168. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfs168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtiol E, Amat C, Thévenet M, Messaoudi B, Garcia S, Buonviso N. Reshaping of Bulbar Odor Response by Nasal Flow Rate in the Rat. PLoS ONE. 2011a;6:e16445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016445. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtiol E, Hegoburu C, Litaudon P, Garcia S, Fourcaud-Trocmé N, Buonviso N. Individual and synergistic effects of sniffing frequency and flow rate on olfactory bulb activity. J. Neurophysiol. 2011b;106:2813–2824. doi: 10.1152/jn.00672.2011. doi:10.1152/jn.00672.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman DC, Struve MF, Wong BA, Gross EA, Parkinson C, Willson GA, Tan Y-M, Campbell JL, Teeguarden JG, Clewell HJ, Andersen ME. Derivation of an Inhalation Reference Concentration Based upon Olfactory Neuronal Loss in Male Rats following Subchronic Acetaldehyde Inhalation. Inhal. Toxicol. 2008;20:245–256. doi: 10.1080/08958370701864250. doi:10.1080/08958370701864250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Strowbridge BW. Transient Activity Induces a Long-Lasting Increase in the Excitability of Olfactory Bulb Interneurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2008;99:187–199. doi: 10.1152/jn.00526.2007. doi:10.1152/jn.00526.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa S, Nakayama T, Watanabe M, Matsuzawa T. Flow mechanisms in the human olfactory groove: numerical simulation of nasal physiological respiration during inspiration, expiration, and sniffing. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:156–162. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2008.530. doi:10.1001/archoto.2008.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabilan S, Lin C-L, Hoffman EA. Characteristics of airflow in a CT-based ovine lung: a numerical study. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007;102:1469–1482. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01219.2005. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01219.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuprat A, Khamayseh A, George D, Larkey L. Volume Conserving Smoothing for Piecewise Linear Curves, Surfaces, and Triple Lines. J. Comput. Phys. 2001;172:99–118. doi:10.1006/jcph.2001.6816. [Google Scholar]

- Kuprat AP, Einstein DR. An anisotropic scale-invariant unstructured mesh generator suitable for volumetric imaging data. J. Comput. Phys. 2009;228:619–640. doi: 10.1016/j.jcp.2008.09.030. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2008.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C-L, Tawhai MH, Hoffman EA. Multiscale image-based modeling and simulation of gas flow and particle transport in the human lungs. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2013;5:643–655. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1234. doi:10.1002/wsbm.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd S. Least squares quantization in PCM. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 1982;28:129–137. doi:10.1109/TIT.1982.1056489. [Google Scholar]

- Lorensen WE, Cline HE. Proceedings of the 14th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques. SIGGRAPH '87. ACM; New York, NY, USA: 1987. Marching Cubes: A High Resolution 3D Surface Construction Algorithm; pp. 163–169. doi:10.1145/37401.37422. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan KT, Monticello TM. Airflow, gas deposition, and lesion distribution in the nasal passages. Environ. Health Perspect. 1990;85:209–218. doi: 10.1289/ehp.85-1568327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JB. Uptake of acetaldehyde vapor and aldehyde dehydrogenase levels in the upper respiratory tracts of the mouse, rat, hamster, and guinea pig. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. Off. J. Soc. Toxicol. 1997;35:91–100. doi: 10.1006/faat.1996.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JB, Blanchard KT. Upper respiratory tract deposition of inspired acetaldehyde. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1992;114:140–146. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(92)90106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overton JH, Graham RC, Miller FJ. A model of the regional uptake of gaseous pollutants in the lung: II. The sensitivity of ozone uptake in laboratory animal lungs to anatomical and ventilatory parameters. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1987;88:418–432. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(87)90216-x. doi:10.1016/0041-008X(87)90216-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plowchalk DR, Andersen ME, Bogdanffy MS. Physiologically based modeling of vinyl acetate uptake, metabolism, and intracellular pH changes in the rat nasal cavity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1997;142:386–400. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.8052. doi:10.1006/taap.1996.8052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter JD, Campbell J, Kimbell JS, Conolly RB, Clewell HJ, Andersen ME. Effects of endogenous formaldehyde in nasal tissues on inhaled formaldehyde dosimetry predictions in the rat, monkey, and human nasal passages. Toxicol. Sci. Off. J. Soc. Toxicol. 2014;138:412–424. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft333. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kft333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter JD, Kimbell JS, Gross EA, Willson GA, Dorman DC, Tan Y-M, Clewell HJ. Application of Physiological Computational Fluid Dynamics Models to Predict Interspecies Nasal Dosimetry of Inhaled Acrolein. Inhal. Toxicol. 2008;20:227–243. doi: 10.1080/08958370701864235. doi:10.1080/08958370701864235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeguarden JG, Bogdanffy MS, Covington TR, Tan C, Jarabek AM. A PBPK Model for Evaluating the Impact of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Polymorphisms on Comparative Rat and Human Nasal Tissue Acetaldehyde Dosimetry. Inhal. Toxicol. 2008;20:375–390. doi: 10.1080/08958370801903750. doi:10.1080/08958370801903750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachowiak M. All in a Sniff: Olfaction as a Model for Active Sensing. Neuron. 2011;71:962–973. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.030. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z, Xu Z, Li B, Xu F. Numerical Simulation of Airway Dimension Effects on Airflow Patterns and Odorant Deposition Patterns in the Rat Nasal Cavity. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077570. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Choi J, Hoffman EA, Tawhai MH, Lin C-L. A multiscale MDCT image- based breathing lung model with time-varying regional ventilation. J. Comput. Phys., Multi-scale Modeling and Simulation of Biological Systems. 2013;244:168–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jcp.2012.12.007. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]