Abstract

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is an acute inflammatory disease of the exocrine pancreas. In Japan, nationwide epidemiological surveys have been conducted every 4 to 5 years by the Research Committee of Intractable Pancreatic Diseases, under the support of the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan. We reviewed the results of the nationwide surveys focusing on the severity assessment and changes in the therapeutic strategy for walled-off necrosis. The severity assessment system currently used in Japan consists of 9 prognostic factors and the imaging grade on contrast-enhanced computed tomography. By univariate analysis, all of the 9 prognostic factors were associated with AP-related death. A multivariate analysis identified 4 out of the 9 prognostic factors (base excess or shock, renal failure, systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria, and age) that were associated with AP-related death. Receiver-operating characteristics curve analysis showed that the area under the curve was 0.82 for these 4 prognostic factors and 0.84 for the 9 prognostic factors, suggesting the comparable utility of these 4 factors in the severity assessment. We also examined the temporal changes in treatment strategy for walled-off necrosis in Japan according to the 2003, 2007, and 2011 surveys. Step-up approaches and less-invasive endoscopic therapies were uncommon in 2003 and 2007, but became popular in 2011. Mortality has been decreasing in patients who require intervention for walled-off necrosis. In conclusion, the nationwide survey revealed the comparable utility of 4 prognostic factors in the severity assessment and the increased use of less-invasive, step-up approaches with improved clinical outcomes in the management of walled-off necrosis.

Keywords: Endoscopic necrosectomy, Diagnostic criteria, Epidemiology, Pancreatic pseudocyst, Systemic inflammatory response syndrome, Step-up approach, Walled-off necrosis

Core tip: We analyzed the results of nationwide epidemiological surveys of acute pancreatitis in Japan to clarify the utility of the prognostic factor scores in the severity assessment and the trend in the treatment of walled-off necrosis. Among the 9 prognostic factors, 4 factors including base excess or shock, renal failure, systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria, and age were associated with mortality by multivariate analysis. Receiver operating characteristics curve analysis demonstrated the comparable utility of these 4 factors to the 9 factors in the severity assessment. Less-invasive, step-up approaches with improved clinical outcomes have become popular in the management of walled-off necrosis.

INTRODUCTION

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is an acute inflammatory disease of the pancreas characterized by the sudden onset of upper abdominal pain, nausea, emesis, and an increase of pancreatic digestive enzymes in the serum and urine[1-4]. Most patients with AP have a mild disease that only affects the pancreas and resolves spontaneously. However, 10%-20% of the patients develop necrosis of the pancreas and multiple organ failure, which may eventually lead to death[1-5]. AP is the most common digestive disease requiring hospitalization in the United States[6].

In Japan, nationwide epidemiological surveys of AP have been conducted every 4 to 5 years mainly by the Research Committee of Intractable Pancreatic Diseases, with the support of the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan[5,7,8]. The latest survey was conducted targeting the AP patients treated in 2011[5]. A detailed analysis of the nationwide surveys would enable us to understand the current status of AP management and the issues that remain to be clarified. In this editorial, we review the results of the surveys focusing on the severity assessment and changes in the therapeutic strategy for walled-off necrosis (WON).

OVERVIEW OF THE NATIONWIDE SURVEY

The nationwide survey consisted of 2-staged postal surveys. The first survey aimed to estimate the number of patients with AP and the second survey aimed to elucidate the clinical-epidemiological characteristics of AP. The departments of internal medicine, gastroenterology, surgery, digestive surgery, and emergency all over Japan were listed and subjected to stratified random sampling. The sampling rates were 5%, 10%, 20%, 40%, 80%, 100%, and 100% for the stratum of hospitals with < 100 beds, ≤ 100 to < 200 beds, ≤ 200 to < 299 beds, ≤ 300 to < 399 beds, ≤ 400 to < 499 beds, ≤ 500 beds, and the affiliated university hospitals, respectively. Several departments treating many pancreatic disease patients and emergency centers were classified as a special stratum, and all of them were selected. In the first survey, a questionnaire requesting a report of the number of patients with AP was sent. The second questionnaire regarding detailed clinicoepidemiological information was sent to departments reporting on the first questionnaire that they had seen AP patients. Clinical data of 2694 patients with AP were collected in the 2011 survey[5], of 2256 patients in the 2007 survey[7], and of 1779 patients in the 2003 survey[8]. In the 2011 survey, the second questionnaire included questions about etiology/symptoms, laboratory data, imaging findings, therapy, complications, and prognosis. The laboratory data and clinical symptoms that were included in the prognostic factor scores in addition to contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) imaging grade were primarily assessed at admission[5].

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF AP IN JAPAN

The latest nationwide epidemiological survey estimated the total number of AP patients in Japan in 2011 as 63080, with an overall prevalence of 49.4 per 100000 persons[5]. Previous studies showed that the incidence of AP in the United States was 10.6 per 10000 person-years in 2009 and that it was 14.7 per 100000 person-years in the Netherlands in 2005[9,10]. These results suggest that the incidence of AP might vary among different populations. The estimated number of AP patients increased to 57560 in the 2007 survey[7] from 35300 in the 2003 survey[8]. AP mostly occurs in those middle-aged to elderly. In the 2011 survey, the mean age of the AP patients was 60.9, and the sex ratio (male to female) was 1.9. The most frequently affected ages were 60 to 69 years in men and 70 to 79 years in women. The three major causes of AP are alcohol, biliary, and idiopathic. Alcohol was the leading cause (46.2%) in men, followed by biliary (19.7%), and idiopathic (13.4%). Biliary was the leading cause (40.3%) in women followed by idiopathic (22.8%) and alcohol (9.9%). The age distribution differed according to the etiology. Alcoholic pancreatitis was most frequently seen from ages 50 to 59, whereas biliary or idiopathic pancreatitis cases increased according to age. In cases of severe AP, the proportion of alcoholic cases increased from 30.9% in 2007 to 42.0% in 2011. A case control study in Japan showed that the risk of alcoholic AP increased as daily alcohol consumption increased[11]. The odds ratio (95%CI) for daily alcohol consumption of 20 ≤ to < 40 g, 40 ≤ to < 60 g, 60 ≤ to < 80 g, 80 ≤ to < 100 g, and ≥ 100 g were 1.7 (0.9-3.0), 3.1 (1.6-5.9), 4.2 (2.1-8.2), 5.3 (2.4-12.0), and 6.4 (3.4-12.4), respectively[11]. Another Japanese study showed that women developed alcohol-related AP 6.8 years earlier compared to men[12,13]. The duration of alcohol consumption was shorter, and the cumulative amounts of alcohol consumption before the development of alcoholic AP were smaller in women than in men. In 2011, the overall mortality of AP was found to be 2.6% and in severe AP, 10.1%[5].

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA OF SEVERE AP IN JAPAN

The severity assessment system for AP (2008) currently used in Japan consists of prognostic factor scores based on 9 clinical parameters and the CECT imaging grade (Table 1). If the total prognostic factor score is ≥ 3 or the CECT grade is ≥ 2, the patient is defined as having severe AP. The previous severity assessment system proposed in 2002 was more complicated than the 2008 system; it consisted of 5 clinical parameters, 10 blood test items, and CT findings. In cases with a severity score ≥ 2, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria and age should be considered in the severity score[14,15]. Several reports have shown that the severity scoring system of AP (2008) is more useful and easier for the prediction of prognosis than the previous one (2002)[14,15]. Of note, diagnosis of severe AP can be performed by CECT grade only, which enables diagnosis of AP with a low prognostic factor score. However, no previous large-scale multicenter studies have validated this system. To validate the prognostic factor score in the diagnosis of severe AP, we analyzed the nationwide survey in 2011. The outcome was AP-related hospital mortality assessed by a univariate logistic regression analysis. A predictive accuracy receiver-operating characteristics (ROC) curve was generated, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine (article#: 2015-1-519).

Table 1.

The severity scoring criteria of acute pancreatitis defined by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (2008)

| Prognostic factor | |

| Base excess ≤ -3 mEq/L or shock (systolic blood pressure < 80 mmHg) | |

| PaO2 ≤ 60 mmHg or respiratory failure (needing respirator) | |

| BUN ≥ 40 mg/dL (or Cr ≥ 2 mg/dL) or oliguria (< 400 mL/d even after fluid therapy) | |

| Elevation of LDH twice or more than upper normal limit | |

| Platelet count ≤ 100000/μL | |

| Serum calcium ≤ 7.5 mg/dL | |

| CRP ≥ 15 mg/dL | |

| Meeting 3 or more SIRS criteria (body temperature > 38 °C or < 36 °C, heart rate > 90/min, respiratory rate > 20/min or PaCO2 < 32 torr, WBC > 12000/μL or < 4000/μL or > 10% immature leukocyte) | |

| Age ≥ 70 yr | |

| Classification of CT grade by contrast-enhanced CT | |

| Factor 1: Extent of extrapancreatic inflammation | |

| To the anterior pararenal extraperitoneal space | 0 point |

| To the root of mesocolon | 1 point |

| Further than inferior pole of kidney | 2 points |

| Factor 2: Less-enhanced region of pancreas (divided into three segments; head, body and tail) | |

| Localized within one segment or limited to peripheral pancreas | 0 point |

| Occupies two segments | 1 point |

| Occupies more than two segments | 2 points |

| Sum of factor 1 and factor 2 ≤ 1 | grade 1 |

| Sum of factor 1 and factor 2 = 2 | grade 2 |

| Sum of factor 1 and factor 2 ≥ 3 | grade 3 |

Severe acute pancreatitis is defined as fulfilling 3 or more criteria of prognostic factors or revealing CT grade 2 or more. BUN: Blood urea nitrogen; Cr: Creatinine; CRP: C-reactive protein; CT: Computed tomography; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; SIRS: Systemic inflammatory response syndrome; WBC: White blood cells.

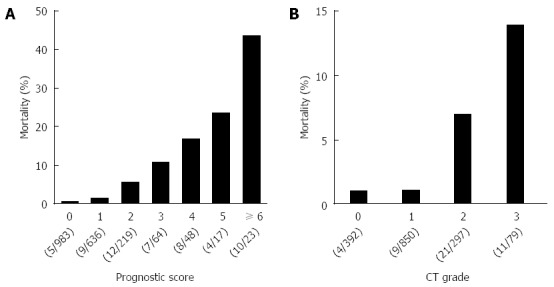

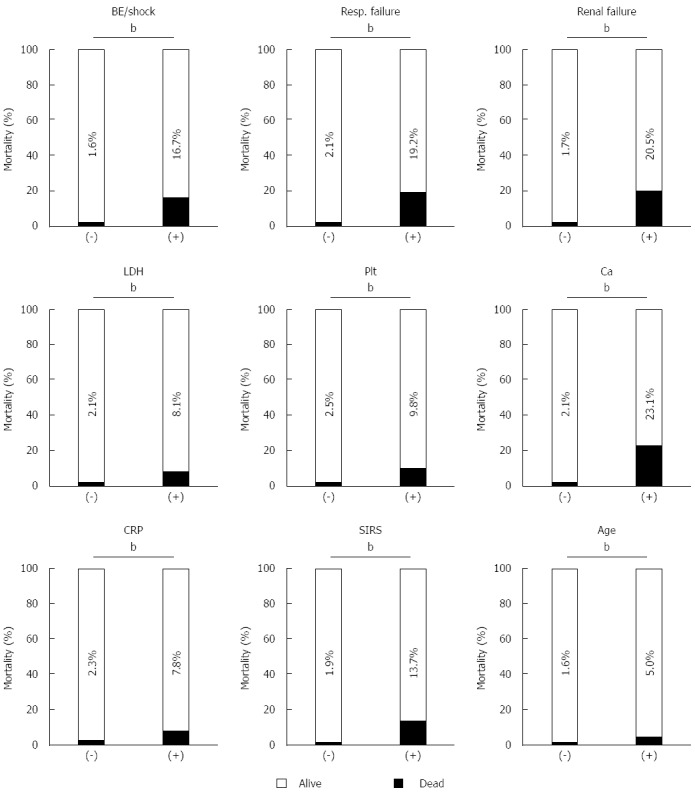

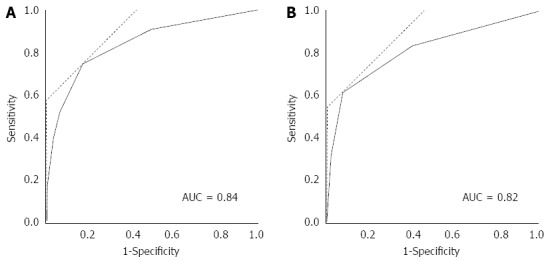

Data about the prognostic factor scores at admission and prognosis were available for 1990 cases with AP. The mortality increased according to the prognostic factor score (Figure 1A). In patients whose prognostic factor scores were ≥ 6, the mortality was as high as 43.5%. Data about the CT grades at admission and prognosis were available in 1618 cases with AP. The mortality increased according to the CT grade (Figure 1B). As shown in Figure 2, mortality was higher if any of the prognostic scores appeared. By univariate analysis, all of the prognostic factors were associated with AP-related death (Table 2). A multivariate analysis identified 4 out of the 9 prognostic factors (base excess or shock, renal failure, SIRS criteria, and age) that were associated with AP-related death. We also performed ROC curve analysis to evaluate the predictive accuracy of the prognostic factor scores for mortality. As shown in Figure 3A, the AUC of the prognostic factor score for predicting mortality was 0.84. If the cut-off point was set at a severity score of 3, as adopted currently, the sensitivity reached 0.53 with a specificity of 0.94. If the cut-off point was set at a severity score of 2, the sensitivity reached 0.75 with a specificity of 0.83. If we adopted the 4 prognostic factors found to be associated with AP-related death by a multivariate analysis, the AUC for predicting mortality was 0.82 (Figure 3B). The sensitivity reached 0.62 with a specificity of 0.92 if the cut-off point was set at score 2. These values were comparable or superior to those for the current severity assessment system using the 9 prognostic factor scores.

Figure 1.

Mortality of the acute pancreatitis patients with the prognostic factor scores and computed tomography grades. A: Mortality of the 1990 AP patients stratified by the prognostic factor scores is shown. B: Mortality of the 1618 AP patients stratified by the CT grades is shown. AP: Acute pancreatitis; CT: Computed tomography.

Figure 2.

Mortality was higher if any of the prognostic factor items were positive. The mortality of the AP patients was assessed in the presence or absence of each prognostic factor items. bP < 0.01 (χ2 test). AP: Acute pancreatitis; BE: Base excess; BUN: Blood urea nitrogen; SIRS: Systemic inflammatory response syndrome; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis showing association of each prognostic factor with acute pancreatitis-related death

| OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Univariate analysis | ||

| BE ≤ -3 mEq/L or shock | 12.1 (6.8-21.1) | < 0.0001 |

| PaO2 ≤ 60 mmHg or respiratory failure | 11.1 (5.7-20.9) | < 0.0001 |

| BUN ≥ 40 mg/dL (or Cr ≥ 2 mg/dL or oliguria) | 14.9 (8.3-26.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Elevation of LDH (twice or more than UNL) | 4.2 (2.3-7.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Platelet count ≤ 100000/μL | 4.2 (1.6-9.5) | 0.007 |

| Serum calcium ≤ 7.5 mg/dL | 14.1 (7.2-26.8) | < 0.0001 |

| CRP ≥ 15 mg/dL | 3.6 (1.9-6.7) | 0.0003 |

| Meeting 3 or more SIRS criteria | 8.4 (4.7-14.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Age ≥ 70 yr | 3.2 (1.8-5.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||

| BE ≤ -3 mEq/L or shock | 2.8 (1.3-6.1) | 0.012 |

| PaO2 ≤ 60 mmHg or respiratory failure | 1.9 (0.8-4.4) | 0.130 |

| BUN ≥ 40 mg/dL (or Cr ≥ 2 mg/dL or oliguria) | 3.8 (1.8-7.8) | 0.0008 |

| Elevation of LDH (twice or more than UNL) | 1.5 (0.7-3.0) | 0.280 |

| Platelet count ≤ 100000/μL | 1.8 (0.6-4.9) | 0.300 |

| Serum calcium ≤ 7.5 mg/dL | 2.5 (0.99-6.1) | 0.051 |

| CRP ≥ 15 mg/dL | 1.0 (0.4-2.2) | 0.980 |

| Meeting 3 or more SIRS criteria | 2.3 (1.0-4.7) | 0.038 |

| Age ≥ 70 yr | 3.5 (1.9-6.6) | < 0.0001 |

BE: Base excess; BUN: Blood urea nitrogen; CRP: C-reactive protein; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; SIRS: Systemic inflammatory response syndrome; UNL: Upper normal limit.

Figure 3.

Receiver-operating characteristics curve analysis of the prognostic factor items. ROC curve analysis of the 9 (A) or 4 (B) prognostic factor items. AUC for predicting mortality was 0.84 for the 9 prognostic factor items and 0.82 for the 4 prognostic factors (base excess or shock, renal failure, SIRS criteria and age) and was found to be associated with AP-related death by a multivariate analysis. SIRS: Systemic inflammatory response syndrome; ROC: Receiver-operating characteristics curve; AUC: Area under the curve; AP: Acute pancreatitis.

In the 2011 survey, the mortality of the patients defined as severe AP solely based on the prognostic factor scores was 7.5%[5]. The mortality of patients defined as severe AP based on the CT grade was 4.2%. The mortality was 25.9% in patients who were defined as severe for both prognostic factors and CT grade. In the revised Atlanta classification, severe AP is defined as the presence of persistent organ failure for more than 48 h[16]. In other words, using the Atlanta classification, severe AP cannot be diagnosed within 48 h of AP onset. CECT, especially used in combination with the prognostic factor score, could be useful to diagnose severe AP in patients at high risk of death in the early stages of AP.

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH SEVERITY AND PROGNOSIS

Because the nationwide epidemiological survey collected detailed laboratory data and information about the clinical course of patients, analysis of the nationwide survey data would be useful to identify and validate factors associated with the severity and prognosis of patients with AP. For example, Kikuta et al[17] reported that impaired glucose tolerance might have an impact on the development and clinical outcome of AP based on an analysis of the nationwide survey in 2007. They showed that idiopathic, but not alcoholic or biliary, AP patients with diabetes mellitus had higher mortality than those without diabetes mellitus.

Very recently, Nawaz et al[18] from the United States reported that elevated serum triglycerides (TGs) were associated with organ failure in AP. They showed that elevated serum TGs measured within 72 h of presentation were correlated with persistent organ failure. Because the body size and contribution of hypertriglyceridemia (HTG) to the etiology of AP vary among different populations[5,19], we validated the clinical impact of HTG in 998 AP patients using the 2011 survey data[20]. The frequencies of severe AP, persisting renal failure, and the necessity for intensive care unit treatment were higher in patients whose serum TG exceeded 200 mg/dL. The high-TG group patients were younger, predominantly male, obese, diabetic, and alcoholic.

However, the characteristics of the subjects were different between our study and the study by Nawaz et al[18]. The nationwide survey covered a wide range of hospitals and was not restricted to tertiary referral hospitals. The frequency of persistent organ failure was relatively low (4.9%) compared to the study by Nawaz et al[18] (26.9%). Subjects with a body mass index > 30% accounted for 43.8% of the patients in the study by Nawaz et al[18], whereas they accounted for only 4.8% in our study. Nevertheless, the nationwide survey confirmed that subjects with HTG are at high-risk for organ failure and require intensive care.

Age is also an important prognostic factor of patients with severe AP and it is included in the Japanese severity assessment system as well as in Ranson’s criteria[21]. The mortality rate of severe AP patients younger than 30 years was 0%, but in those older than 80 years it exceeded 20%[5]. The high mortality rate in aged patients was mainly due to organ failure, such as cardiovascular, respiratory, and renal failure. The higher mortality in aged patients will remain an important issue in the management of AP in aging countries like Japan.

MANAGEMENT OF WON IN JAPAN

The revised Atlanta classification for AP[16] defined WON, a disease entity previously known as pancreatic abscess or pseudocyst, as an encapsulated collection of necrotic tissue that develops later than 4 wk after the onset of AP. Infection of the necrotic tissue often requires prompt intervention, that had previously been performed primarily by open surgical approaches[22]. However, open surgical debridement of necrotizing pancreatitis is accompanied by a high hospital mortality of up to 23%[23].

Recent advances in less-invasive, endoscopic approaches for WON treatment resulted in better clinical outcomes. A randomized, multicenter study clearly showed better clinical outcomes from the step-up approach over primary open necrosectomy in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis[24]. The management of WON has shifted from open surgical treatment to minimally invasive approaches. Due to its lower morbidity rate compared to surgical approaches, endoscopic treatment may be the preferred first-line approach for the treatment of WON[25].

To clarify the temporal changes in the treatment strategy and prognosis of WON in patients with AP in Japan, we analyzed the anonymous data of local complications collected by the 3 nationwide surveys in 2003, 2007, and 2011[5,7,8]. In the 2011 survey, information about the local complications was available for 350 patients. Because the term “pseudocyst” had been often used to describe a condition resembling WON in Japan, patients with pseudocysts later than 4 wk after the AP onset were included in this study. At the time of the 2011 survey, the revised Atlanta classification for AP was not published yet and the term “WON” had not been well recognized in Japan.

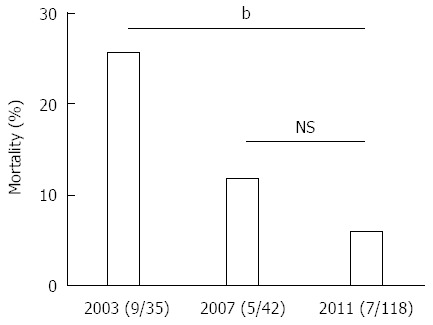

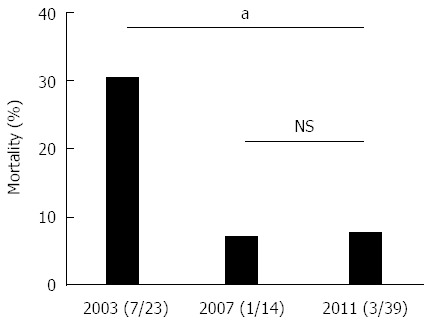

The characteristics of the patients with WON (n = 124) were compared to those without WON (n = 226) (Table 3). Patients with WON were predominantly male, had more severe AP, and had higher CT imaging grades. In the 2003 and 2007 surveys, patients with pancreatic abscesses and/or intraabdominal abscesses were analyzed (n = 36 and n = 45, respectively). These patients were regarded herein as those with WON. The mortality of patients with WON due to AP-related events was 25.7% (9/35) in 2003, 11.9% (5/42) in 2007, and 5.9% (7/118) in 2011 (Figure 4). The mortality of AP patients with WON was significantly lower in 2011 compared to that in 2003 (P = 0.0008, χ2 test).

Table 3.

Comparison of the characteristics of patients with or without walled-off necrosis in 2011 survey n (%)

| WON (+), n = 124 | WON (-), n = 226 | P value | |

| Median age (IQR) | 59 (50-70) | 62.5 (50-74) | 0.1901 |

| Male sex | 102 (82.3) | 164 (72.6) | 0.0422 |

| Severe pancreatitis | 56 (45.2) | 65 (28.8) | 0.0022 |

| Severity score ≥ 3 | 19 (15.3) | 23 (10.2) | 0.1602 |

| Severity score < 3 | 105 (84.7) | 203 (89.8) | |

| CT grade ≥ 2 | 51 (41.1) | 54 (23.9) | 0.0012 |

| CT grade < 2 | 51 (41.1) | 137 (60.6) | |

| CT grade unknown | 22 (17.7) | 35 (15.5) | |

| Etiology | |||

| Biliary | 23 (18.6) | 42 (18.6) | 0.9802 |

| Alcohol | 52 (41.9) | 96 (42.5) | |

| Idiopathic | 20 (16.1) | 37 (16.4) | |

| Others | 26 (21.0) | 43 (19.0) | |

| Unknown | 3 (2.4) | 8 (3.5) |

t-test;

χ2 test. CT: Computed tomography; IQR: Interquartile range; WON: Walled-off necrosis.

Figure 4.

Temporal changes in mortality of patients with walled-off necrosis. Mortality of the patients with WON in the 2003, 2007, and 2011 surveys is shown. bP < 0.01 (χ2 test). NS: Not significant; WON: Walled-off necrosis.

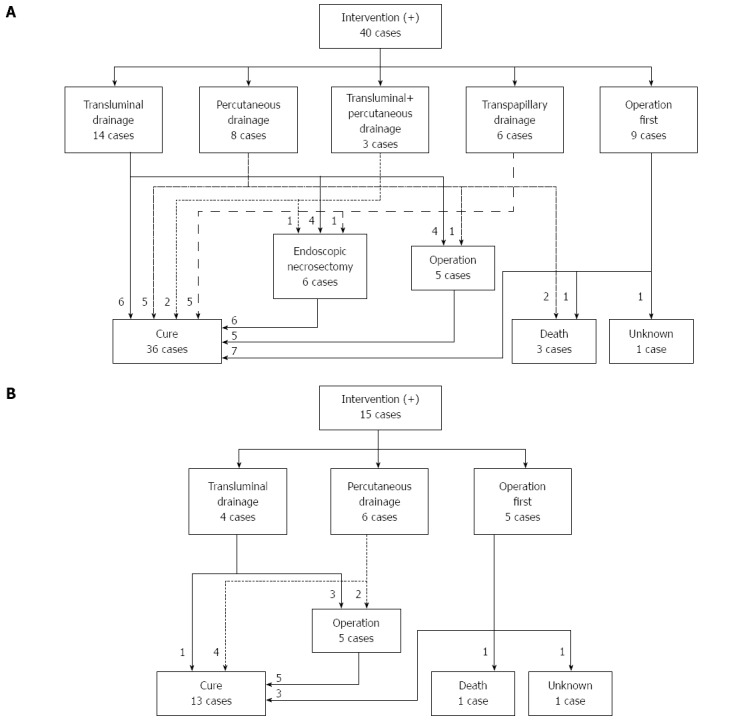

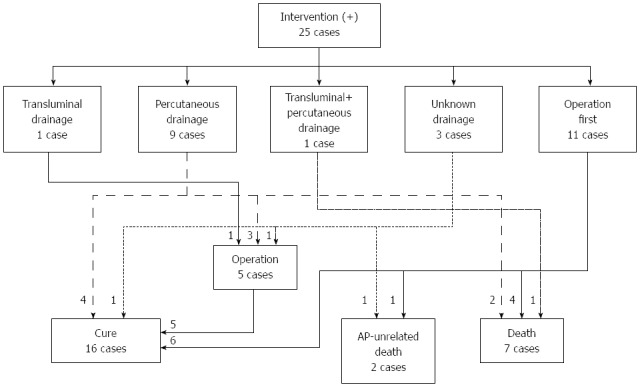

Forty patients in the 2011 survey, 15 in the 2007 survey, and 25 patients in the 2003 survey required interventions for WON. In the 2011 survey, 9 of the 40 patients received open surgery as an initial treatment (Figure 5A). The other 31 patients received drainage therapies via transluminal, percutaneous, or transpapillary routes. Eighteen of the 31 patients were cured by drainage therapies alone. Endoscopic necrosectomy and surgery were performed in 6 and 5 patients, respectively. These 11 patients that received step-up approaches (drainage plus endoscopic necrosectomy or surgery) were cured. In the 2007 survey, 5 out of the 15 patients received surgery first (Figure 5B). The other patients received drainage therapies and half of these patients were cured. The remaining 5 patients required surgery, and all of these patients were cured. In the 2003 survey, 11 out of 25 patients received surgery first (Figure 6). Among these patients, 4 patients died due to AP-related events. Other patients received drainage therapies, and 3 patients died. Five patients were cured by drainage therapies only and 5 patients required additional surgery (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Flow-chart of treatment strategy for walled-off necrosis in the patients in the 2011 (A) and 2007 (B) surveys. A: The treatment strategy for the 40 patients who required intervention for WON in the 2011 survey is shown. B: The treatment strategy for the 15 patients who required intervention for WON in the 2007 survey is shown. WON: Walled-off necrosis.

Figure 6.

Flow-chart of treatment strategy for walled-off necrosis in the acute pancreatitis patients in the 2003 survey. The treatment strategy for the 25 patients who required intervention for WON in the 2003 survey is shown. AP: Acute pancreatitis WON: Walled-off necrosis.

The mortality of patients with WON receiving interventions was significantly lower in 2011 than that in 2003 (Figure 7). The mortality of the patients who required interventions was 30.4% (7/23) in 2003, 7.1% (1/14) in 2007, and 7.7% (3/39) in 2011 (excluding those with AP-unrelated deaths and unknown outcomes). In the 2003 survey, 44% (11/25) of the patients received surgery first treatment, and this ratio was reduced to 22.5% (9/40) in the 2011 survey. It is assumed that the proportion of patients receiving surgery first treatment has been decreasing further in recent years, because endoscopic necrosectomy has become popular since 2011[25]. Mortality would be further reduced by technical improvements in endoscopic interventions, such as balloon dilatation of a punctured tract, the placement of multiple plastic stents and a biflanged metal stent optimized for re-intervention[26,27].

Figure 7.

Temporal changes in mortality of patients with walled-off necrosis who received intervention. Mortality of the patients with WON in the 2003, 2007, and 2011 surveys is shown. aP < 0.05 (χ2 test). NS: Not significant; WON: Walled-off necrosis.

Less-invasive endoscopic approaches for WON were accompanied by lower mortality, but several complications have been reported. Bleeding is the most common complication, followed by perforation and other rare complications[28]. Failure to control bleeding by an endoscopic approach will result in surgery or interventional radiology. A recent report described a standardized approach for endoscopic necrosectomy that could reduce the complication ratio, as defined by the assessment and management checklist for WON[29]. Such guidelines for the required equipment and backup preparations will further improve the clinical outcomes of WON treatment.

CONCLUSION

We reviewed the latest nationwide survey of AP in Japan. Nationwide surveys conducted regularly have provided us with updated information on the management of AP on a large, multicenter scale in Japan. Future studies on unsolved issues, including the development of a more accurate and convenient severity assessment system and the optimization of therapeutic algorithms for the treatment of WON, would contribute to improved outcomes in this intractable disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Drs. Makoto Otsuki and Yasuyuki Kihara for the 2003 nationwide survey.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty Type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of Origin: Japan

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: April 18, 2016

First decision: May 12, 2016

Article in press: June 13, 2016

P- Reviewer: Bramhall S, Chung MJ, Fujino Y, Inal V S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Frossard JL, Steer ML, Pastor CM. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 2008;371:143–152. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakker OJ, Issa Y, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Schepers NJ, Bruno MJ, Boermeester MA, Gooszen HG. Treatment options for acute pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:462–469. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu BU, Banks PA. Clinical management of patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1272–1281. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afghani E, Pandol SJ, Shimosegawa T, Sutton R, Wu BU, Vege SS, Gorelick F, Hirota M, Windsor J, Lo SK, et al. Acute Pancreatitis-Progress and Challenges: A Report on an International Symposium. Pancreas. 2015;44:1195–1210. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamada S, Masamune A, Kikuta K, Hirota M, Tsuji I, Shimosegawa T. Nationwide epidemiological survey of acute pancreatitis in Japan. Pancreas. 2014;43:1244–1248. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, Crockett SD, McGowan CE, Bulsiewicz WJ, Gangarosa LM, Thiny MT, Stizenberg K, Morgan DR, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179–1187.e1-3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satoh K, Shimosegawa T, Masamune A, Hirota M, Kikuta K, Kihara Y, Kuriyama S, Tsuji I, Satoh A, Hamada S. Nationwide epidemiological survey of acute pancreatitis in Japan. Pancreas. 2011;40:503–507. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318214812b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otsuki M, Hirota M, Arata S, Koizumi M, Kawa S, Kamisawa T, Takeda K, Mayumi T, Kitagawa M, Ito T, et al. Consensus of primary care in acute pancreatitis in Japan. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3314–3323. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i21.3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNabb-Baltar J, Ravi P, Isabwe GA, Suleiman SL, Yaghoobi M, Trinh QD, Banks PA. A population-based assessment of the burden of acute pancreatitis in the United States. Pancreas. 2014;43:687–691. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spanier B, Bruno MJ, Dijkgraaf MG. Incidence and mortality of acute and chronic pancreatitis in the Netherlands: a nationwide record-linked cohort study for the years 1995-2005. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3018–3026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i20.3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kume K, Masamune A, Ariga H, Shimosegawa T. Alcohol Consumption and the Risk for Developing Pancreatitis: A Case-Control Study in Japan. Pancreas. 2015;44:53–58. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masamune A, Kume K, Shimosegawa T. Sex and age differences in alcoholic pancreatitis in Japan: a multicenter nationwide survey. Pancreas. 2013;42:578–583. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31827a02bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masamune A. Alcohol Misuse and Pancreatitis: A Lesson from Meta-Analysis. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:1860–1861. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otsuki M, Takeda K, Matsuno S, Kihara Y, Koizumi M, Hirota M, Ito T, Kataoka K, Kitagawa M, Inui K, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis and severity stratification of acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5798–5805. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i35.5798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ueda T, Takeyama Y, Yasuda T, Kamei K, Satoi S, Sawa H, Shinzeki M, Ku Y, Kuroda Y, Ohyanagi H. Utility of the new Japanese severity score and indications for special therapies in acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:453–459. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102–111. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kikuta K, Masamune A, Shimosegawa T. Impaired glucose tolerance in acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7367–7374. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i24.7367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nawaz H, Koutroumpakis E, Easler J, Slivka A, Whitcomb DC, Singh VP, Yadav D, Papachristou GI. Elevated serum triglycerides are independently associated with persistent organ failure in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1497–1503. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valdivielso P, Ramírez-Bueno A, Ewald N. Current knowledge of hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25:689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamada S, Masamune A, Kikuta K, Shimosegawa T. Clinical Impact of Elevated Serum Triglycerides in Acute Pancreatitis: Validation from the Nationwide Epidemiological Survey in Japan. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:575–576. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ranson JH. Etiological and prognostic factors in human acute pancreatitis: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1982;77:633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forsmark CE, Baillie J. AGA Institute technical review on acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2022–2044. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheung MT, Li WH, Kwok PC, Hong JK. Surgical management of pancreatic necrosis: towards lesser and later. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:338–344. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0251-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Goor H, Schaapherder AF, van Eijck CH, Bollen TL, et al. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491–1502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yasuda I, Nakashima M, Iwai T, Isayama H, Itoi T, Hisai H, Inoue H, Kato H, Kanno A, Kubota K, et al. Japanese multicenter experience of endoscopic necrosectomy for infected walled-off pancreatic necrosis: The JENIPaN study. Endoscopy. 2013;45:627–634. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fabbri C, Luigiano C, Maimone A, Polifemo AM, Tarantino I, Cennamo V. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:479–488. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v4.i11.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mukai S, Itoi T, Baron TH, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided placement of plastic vs. biflanged metal stents for therapy of walled-off necrosis: a retrospective single-center series. Endoscopy. 2015;47:47–55. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Brunschot S, Fockens P, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Voermans RP, Poley JW, Gooszen HG, Bruno M, van Santvoort HC. Endoscopic transluminal necrosectomy in necrotising pancreatitis: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1425–1438. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson CC, Kumar N, Slattery J, Clancy TE, Ryan MB, Ryou M, Swanson RS, Banks PA, Conwell DL. A standardized method for endoscopic necrosectomy improves complication and mortality rates. Pancreatology. 2016;16:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]