Abstract

Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) is a common pathology of the retinal vasculature. Patients with CRVO usually present with a drop in visual acuity. The condition bears no specific therapy; treatment is aimed at the management of potentially blinding complications, of which there are many. With majority of cases being unilateral, bilateral CRVO is usually associated with an underlying systemic illness such as a hyperviscosity syndrome. Here, we present a case of a patient, who presented with a bilateral drop in vision diagnosed as bilateral CRVO on ophthalmic evaluation. Systemic workup revealed the presence of an underlying undiagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. An initial presentation to the ophthalmologist is a rare occurrence in leukemic patients. This case report highlights the role of the ophthalmologist in diagnosing a potentially life-threatening hematological illness.

Keywords: Bilateral Central Retinal Vein Occlusion, Central Retinal Vein Occlusion, Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

INTRODUCTION

Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) is a common cause of vision impairment which can occur at any given age. Most of the cases are unilateral; bilateral cases are rare, usually having an underlying systemic illness such as a hyperviscosity syndrome or an inflammatory condition.1 Here, we present the case of a patient, who came to us with a bilateral CRVO and was later diagnosed to have chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and was successfully treated with oral imatinib mesylate for CML and repeated intravitreal bevacizumab injections for macular edema of CRVO, without any complications.

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old Asian Indian male presented with complaints of sudden painless diminution of vision in the right eye followed by left eye over a span of 2 days. There was no history of any other ocular complaints, trauma, or any ocular intervention. The systemic history was unremarkable. There was no history of bleeding tendencies, fainting episodes, and malnutrition or drug intake.

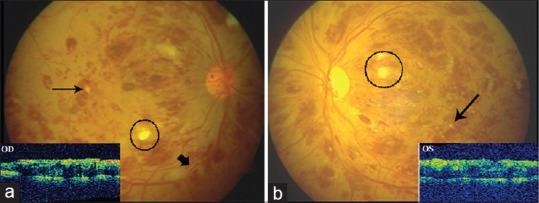

On examination, the best corrected visual acuity was 0.8 logMAR (OD) and 1.0 logMAR (OS). Anterior segment examination revealed a clear cornea with grade one nuclear sclerosis in both eyes. The intraocular pressure was measured to be 14 mmHg (OD) and 17 mmHg (OS) by Goldmann applanation tonometry. Pupils were normal in size and reacting to light and accommodation. Posterior segment examination revealed a clear media with normal sized optic disc and a Cup: Disc ratio of 0.3 in both eyes. The vessels were dilated and tortuous with multiple flame-shaped and dot-blot hemorrhages in all four quadrants of both eyes. Multiple cotton wool spots were visualized. The macula was edematous. There was the presence of Roth's spots in midperiphery in both eyes, yellowish white subretinal infiltrates, and perivenular sheathing suggestive of leukemia [Figure 1a and b]. Fundus fluorescein angiography revealed delayed arteriovenous transit time and areas of capillary nonperfusion and blocked fluorescence due to retinal hemorrhages. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed spongy macular edema in both eyes with a foveal thickness of 536 ± 3 μ (OD) and 530 ± 19 μ (OS) [Figure 1a and b]. Systemic detailed workup of the patient was done to confirm leukemia as the cause of bilateral CRVO. The total leukocyte count was remarkably increased to 2.15 lac/μl. A differential leukocyte count revealed polymorphs 40%, lymphocytes 11%, monocytes 2%, eosinophils 1%, basophils 5%, blasts l3%, myelocytes 16%, metamyelocytes 12%, and platelets of 2.55 lac/μl. Hemato-oncology consultation showed a mild splenomegaly.

Figure 1.

(a) Fundus photograph (OD) showing superficial and deep retinal hemorrhages in all four quadrants with Roth's spots (encircled) in midperiphery, white retinal infiltrates (fine black arrow), and perivascular sheathing (thick arrow). Inset showing spongiform thickening of macula and loss of foveal dip. (b) Fundus photo and optical coherence tomography picture of the left eye (OS) showing similar features

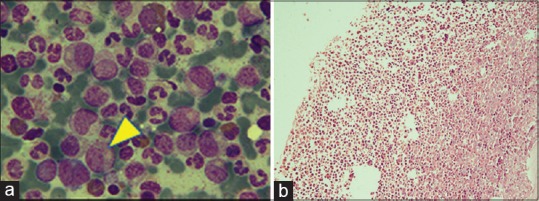

Bone marrow aspiration gave a picture of a hypercellular marrow with 3% blasts and other cells in the maturation stages of myeloid series [Figure 2a]. Trephine biopsy also showed a hypercellular marrow and preponderance of myeloid series showing cells in varying stages of maturation [Figure 2b]. Cytogenetics showed BCR-ABL translocation present in 18 of 25 metaphases studied. The final diagnosis of CML in the chronic phase was made, and the patient was started on oral imatinib mesylate 400 mg once a day.

Figure 2.

(a) Bone marrow aspirate (using May-Grunwald-Giemsa stain, in oil immersion) showing hypercellularity with 3% blasts and cells of myeloid series (yellow arrowhead pointing towards a blast cell). (b) Hematoxylin- and Eosin-stained trephine biopsy (×20) showing hypercellularity, cells in varying stages of maturation and preponderance of myeloid series of cells

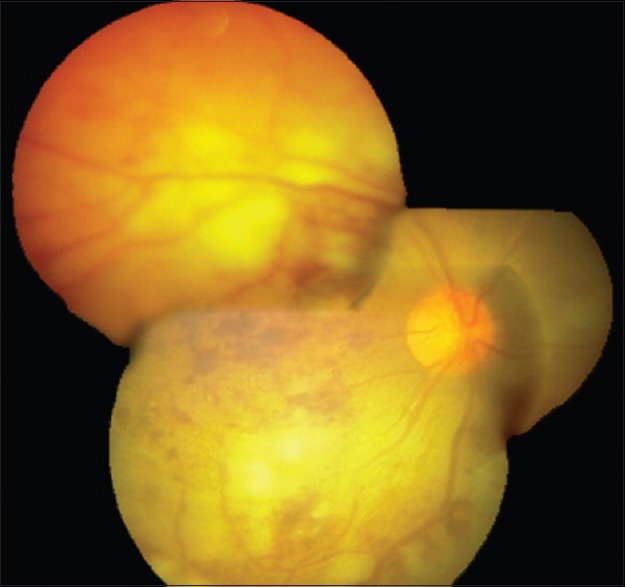

The yellowish retinal infiltrates gradually increased over the next 1 month [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Fundus photo showing increase in the intensity and size of retinal infiltrates, 1-month following initiation of systemic therapy

The patient became systemically stable after 3 months of starting systemic therapy. The subretinal deposits disappeared and retinal hemorrhages decreased considerably. However, neovascularization of the disc was noted, and the patient was subjected to panretinal photocoagulation in both eyes [Figure 2b].

After the systemic status was controlled, intravitreal bevacizumab 0.125 mg in 0.05 ml was injected in the right eye followed by the left eye. The injections were repeated at an interval of 1 month. An OCT at 2 months recorded the central macular thickness (CMT) of 201 ± 55 μ (OD) and 214 ± 44 μ (OS) and the patient regained vision of 0.7 and 0.3 logMAR in OD and OS, respectively. He was kept under regular monthly follow-up, and bevacizumab was given on pro re nata basis. A total of four injections, each of bevacizumab were given over a period of 1 year. The macular edema stabilized after six injections of intravitreal bevacizumab in OD and seven injections in OS.

At the end of 4 years follow-up, the patient is doing well systemically. He is in a period of remission on imatinib mesylate, the total leukocyte count is 5200 mm−3 and logMAR visual acuity of 0.6 and 0.3 in OD and OS, respectively, was documented at the last follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Bilateral CRVO is a rare occurrence. Eye is a window to systemic diseases; a careful ocular examination could clinch the diagnosis and prompt referral to a hemato-oncologist could be lifesaving.

Alexander et al. published the largest case series of three cases with Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia as a cause of bilateral CRVO.2 A similar case with bilateral simultaneous CRVO in Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia was also reported by Chanana et al.3 In these cases, the ocular symptoms improved with improvement in the systemic condition. However, in this case, intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agent was required for stabilization of the ocular condition and resolution of macular edema despite systemic control. Similar reports of bilateral CRVO have also been documented in association with other hypercoagulable states such as hyperhomocysteinemia,4 multiple myeloma,5 and acute myeloid leukemia.6 The above case report points toward an ocular presentation of CML wherein ophthalmic evaluation pointed toward the underlying disease.

Ocular involvement is noted in about one-half of the patients of leukemia at the time of diagnosis7 although it is frequently asymptomatic. Vision loss as the presenting feature of CML is rare and has been reported attributable to bilateral CRVO,8 leukemic retinopathy,9 and proliferative retinopathy.10

In a prospective study of 120 patients with newly diagnosed leukemia of all cell types, Schachat et al. diagnosed a CRVO in five patients - all of whom had myeloid leukemia with extremely high white blood cell counts or platelet counts - and attributed the venous occlusion to blood hyperviscosity.11

Gordon et al.12 emphasized the importance of distinguishing between infectious and neoplastic retinal infiltrates in patients with a history of leukemia. They found that neoplastic (or leukemic) retinal infiltrates occurred in patients who had newly diagnosed leukemia and those patients in blast crisis.

The present case showed an initial increase in leukemic infiltrates as the patient was started on systemic therapy; however, with systemic remission, these disappeared over the course of 3 months. The macular edema due to CRVO remained persistent at this stage and responded to intravitreal bevacizumab injections.

BCR-ABL protein in CML also increases VEGF levels, and imatinib has anti-VEGF properties.13 Notably, after systemic remission with imatinib, the patient showed favorable response to intravitreal anti-VEGF and panretinal photocoagulation. Bevacizumab is contraindicated in patients with bleeding tendencies. In our case, the patient's coagulation profile was normal, and there was no history of bleeding tendencies.

Thus, we conclude that systemic anti-VEGF agents may not be sufficient to overcome the ocular manifestations of the growth factor and intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents would be needed to counteract the high levels of VEGF responsible for ocular morbidity, without any adverse effects.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hayreh SS, Zimmerman B, McCarthy MJ, Podhajsky P. Systemic diseases associated with various types of retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:61–77. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander P, Flanagan D, Rege K, Foss A, Hingorani M. Bilateral simultaneous central retinal vein occlusion secondary to hyperviscosity in Waldenstrom's macroglobulinaemia. Eye (Lond) 2008;22:1089–92. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chanana B, Gupta N, Azad RV. Case report: Bilateral simultaneous central retinal vein occlusion in Waldenström's macroglobulinemia. Optometry. 2009;80:350–3. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelman R, DiMango EA, Schiff WM. Sequential bilateral central retinal vein occlusions in a cystic fibrosis patient with hyperhomocysteinemia and hypergamma-globulinemia. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2013;7:362–7. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e3182965271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aggio FB, Cariello AJ, Almeida MS, Rodrigues CA, De Moraes NS, Colleoni GW, et al. Bilateral central retinal vein occlusion associated with multiple myeloma. Ophthalmologica. 2004;218:283–7. doi: 10.1159/000078622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tseng MY, Chen YC, Lin YY, Chu SJ, Tsai SH. Simultaneous bilateral central retinal vein occlusion as the initial presentation of acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Med Sci. 2010;339:387–9. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181cf31ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kincaid MC, Green WR. Ocular and orbital involvement in leukemia. Surv Ophthalmol. 1983;27:211–32. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(83)90123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wechsler DZ, Tay TS, McKay DL. Life-threatening haematological disorders presenting with opthalmic manifestations. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2004;32:547–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2004.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandic BD, Potocnjak V, Bencic G, Mandic Z, Pentz A, Hajnzic TF. Visual loss as initial presentation of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Coll Antropol. 2005;29(Suppl 1):141–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandava N, Costakos D, Bartlett HM. Chronic myelogenous leukemia manifested as bilateral proliferative retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:576–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schachat AP, Markowitz JA, Guyer DR, Burke PJ, Karp JE, Graham ML. Ophthalmic manifestations of leukemia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:697–700. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070010715033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon KB, Rugo HS, Duncan JL, Irvine AR, Howes EL, Jr, O’Brien JM, et al. Ocular manifestations of leukemia: Leukemic infiltration versus infectious process. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:2293–300. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00817-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legros L, Bourcier C, Jacquel A, Mahon FX, Cassuto JP, Auberger P, et al. Imatinib mesylate (STI571) decreases the vascular endothelial growth factor plasma concentration in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2004;104:495–501. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]