Abstract

Free-electron lasers (FEL) hold the potential to revolutionize structural biology by producing X-ray pules short enough to outrun radiation damage, thus allowing imaging of biological samples without the limitation from radiation damage. Thus, a major part of the scientific case for the first FELs was three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of non-crystalline biological objects. In a recent publication we demonstrated the first 3D reconstruction of a biological object from an X-ray FEL using this technique. The sample was the giant Mimivirus, which is one of the largest known viruses with a diameter of 450 nm. Here we present the dataset used for this successful reconstruction. Data-analysis methods for single-particle imaging at FELs are undergoing heavy development but data collection relies on very limited time available through a highly competitive proposal process. This dataset provides experimental data to the entire community and could boost algorithm development and provide a benchmark dataset for new algorithms.

Subject terms: Biological physics, Virus structures, X-rays

Background & Summary

Free-electron lasers (FEL) provide ultra short and extremely bright pulses of coherent X-rays1. It has been predicted that such pulses could enable structure determination without crystallization by outrunning radiation damage and thus capturing diffraction data before the particle has time to respond and eventually be destroyed by the deposited energy2. Experimental verification of this ‘diffraction-before-destruction’ principle has been demonstrated several times for resolution down to 10 nm (refs 3,4).

Using many such diffraction patterns from multiple copies of a reproducible sample, the patterns could be assembled into a 3D diffraction space from which the 3D structure could be derived5,6. This promise was a main part of the scientific case for building free-electron lasers7. Several examples of 2D reconstructions from biological samples at X-ray FEL have been demonstrated4,8,9 but 3D reconstructions have remained elusive.

A single diffraction pattern represents a curved slice through the Fourier transform of the electron density of the object. For successful 3D reconstruction many diffraction patterns from identical particles need to be assembled into the complete 3D Fourier transform of the particle. This is difficult since the orientation of the injected particles is unknown and has to be recovered from the diffraction data alone. A recent paper10 demonstrates this, using a modified version of the expand, maximize and compress algorithm5 (EMC) on the Mimivirus particle. Here we describe the data collection, data preprocessing and the dataset that was used for this reconstruction.

Today, beam time at free-electron lasers is scarce as there are few facilities and they serve a multitude of scientific disciplines. Furthermore, applications such as 3D imaging require a large amount of effort in algorithm development and testing. Several groups around the world are active in this development but the majority of them don’t have regular beam time access. This dataset can thus serve as a benchmark for algorithm testing and give many more groups access to experimental data.

For any new method, validation tools are of crucial importance. Therefore, together with the 3D reconstruction of the Mimivirus we also presented two new validation methods10. Further development of these methods, and the development of new ones will therefore benefit from being applied to this dataset in particular.

The sample in this dataset is the Mimivirus (Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus)11,12. Mimivirus is part of a recently discovered class of giant DNA viruses. Viral capsid is pseudo-icosahedral with a corner-to-corner diameter of 500 nm and a face-to-face diameter of 400 nm (ref. 13). The virus is covered by fibres with a length of 125 nm giving it a total diameter of 750 nm (ref. 14).

Methods

These methods were described in ref. 10. The description here is more detailed with regards to data collection and on-line data analysis.

Sample injection

Purified Mimivirus particles15 were transferred into a volatile buffer (250 mM ammonium acetate, pH 7.5) and the suspension was aerosolized with helium in a gas dynamic nebulizer16. The aerosol of hydrated and adiabatically cooled particles entered a differentially pumped aerodynamic lens17.

Data collection

Experiments were performed at the Atomic Molecular Optics (AMO) beam line18 of the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) hard X-ray laser1, using the CAMP19 instrument20,21. The experiment was part of an experiment running from June 17 to June 21 of 2010 with proposal number L150. Diffraction data were recorded on a pair of pnCCD detectors19 at a repetition rate of 60 Hz matching the repetition rate of LCLS. The two detectors were placed at a distance of 740 mm from the interaction region with a gap between them of 2.1 mm to let the direct beam through. The pixel size is 75 μm and each detector in the pair has 512×1,024 pixels giving the full setup a pixel count of 1,024×1,024 pixels.

The photon energy was 1.2 keV corresponding to a wavelength of 1.03 nm. At this wavelength the full-period resolution at the edge of the detector is 19.9 nm. The electron bunch used to create the X-ray pulse was 70 fs long (full duration at half maximum) and the X-ray pulse is believed to be shorter than this22. The focus was ~10 μm (full width at half maximum) at the interaction point, giving a power density of ~3.4 1015 W cm−2 or 1012 photons per pulse.

The experiment was performed at a pressure of 10−6 mbar to reduce background scattering. Some of the most important experiment parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of experimental parameters.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Photon energy | 1,200 keV |

| Detector distance | 0.74 m |

| Pixel size | 75 μm |

| Number of pixels | 1,024×1,024 |

| Focal size | 10 μm2 |

On-line data analysis

On-line hit-identification provided real-time statistics that guided injector alignment and tuning. Hits with a high scattering strength were identified by counting the number of pixels that measured a value above a threshold. Diffraction patterns with more than 500 pixels with a value above 170 ADU were defined as a hit. See ref. 21 for a detailed description.

Data Records

Two datasets are provided: the full record of all collected data and a smaller preprocessed dataset. Both data sets are available in the same CXIDB entry (Data Citation 1).

Full data record

We provide all data collected from the Mimivirus at this beamtime before any preprocessing or sorting. This dataset is in the extended tagged container (XTC) file format. This can be converted to HDF5 format using programs such as CASS23 or Cheetah24. This conversion normally also involves preprocessing and the data is therefore provided in the untouched XTC format.

The record contains 19 LCLS runs. 14 of these had the sample injector and X-ray laser turned on while the remaining 5 runs only collected detector background noise. These so called ‘dark runs’ can be used for to better subtract the background from the actual data. Table 2 shows a list of all 19 runs.

Table 2. List of experimental runs.

| Run number | Sample | Number of frames | Number of frames selected for analysis in ref. 10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Runs labeled as dark had the X-ray beam turned off and are included to allow for detector calibration. The lack of good hits before run 90 was possibly fixed by a changed injection nozzle at this point. | |||

| 73 | Dark | 651 | N/A |

| 80 | Mimivirus | 14,273 | 0 |

| 81 | Mimivirus | 14,450 | 0 |

| 82 | Mimivirus | 11,371 | 0 |

| 83 | Dark | 15,636 | N/A |

| 84 | Mimivirus | 65,594 | 0 |

| 87 | Mimivirus | 93,840 | 0 |

| 89 | Dark | 3,821 | N/A |

| 90 | Mimivirus | 77,644 | 30 |

| 91 | Mimivirus | 4,943 | 6 |

| 92 | Mimivirus | 33,721 | 39 |

| 93 | Mimivirus | 43,679 | 24 |

| 94 | Mimivirus | 58,931 | 40 |

| 95 | Mimivirus | 42,083 | 10 |

| 97 | Mimivirus | 36,899 | 33 |

| 98 | Dark | 7,794 | N/A |

| 152 | Dark | 2,498 | N/A |

| 156 | Mimivirus | 64,977 | 3 |

| 157 | Mimivirus | 90,403 | 13 |

Initial hit finding showed that 0.3% of the frames contained diffraction that was stronger than the background. The rest were misses, i.e., frames that were read out when the pulse did not hit any particle. In addition to hits from single Mimivirus particles the hits also include droplets of buffer, clusters of viruses and a few particles that were injected earlier and had stayed in the injection system.

Preprocessed and filtered data

This dataset contains the 198 preprocessed (see ref. 19) diffraction patterns that were used in ref. 10 to recover the 3D structure of the Mimivirus particle. This data is in the CXIDB format described in ref. 25. The pixel values in the data are in arbitrary detector units (ADU). The conversion factor from ADU to number of photons is 7 ADU per photon. Some areas of the detector were unreadable and some scattering angles were not covered by the detector, such as the gap between the two detector halves that lets the direct beam through. These areas are identified by a mask entry in the CXIDB file format.

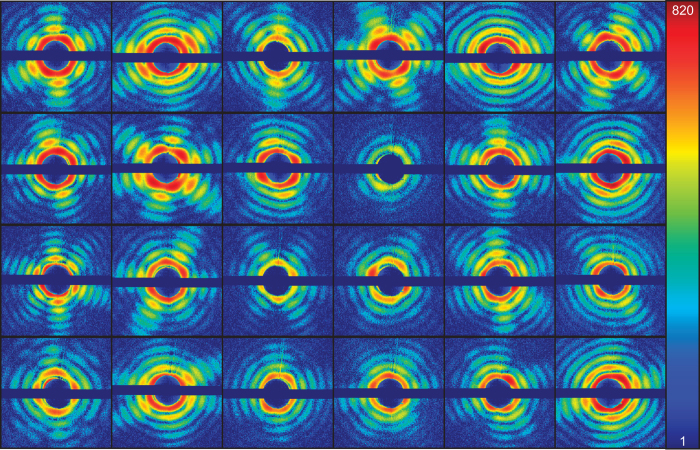

The data was filtered in three steps. (1) Hits were distinguished from blanks using methods described in refs 21 and 24. This yielded 1,600 hits. (2) 307 Diffraction patterns that correspond to a Mimivirus particle were selected by hand. An icosahedral or pseudo-icosahedral particle will in most orientations yield a distinctive type of pattern showing six outwards-going streaks. This feature and particle size, determined from the fringe spacing, was used for this selection. (3) When the detector is exposed to high intensities, the intensity can spill over from a pixel to neighboring pixels. We start seeing these effects at intensities above 750 photons per pixel. In the final dataset, diffraction patterns suffering from this effect were filtered out, resulting in 198 unsaturated diffraction patterns. A subset of this dataset is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. The first 24 of the 198 diffraction patterns in this dataset.

The color scale is logarithmic and ranges from 1 to 820 photons per pixel. This is a modification of a figure previously presented in ref. 10.

Technical Validation

3D reconstruction

The 198 diffraction patterns were successfully assembled in a 3D Fourier volume and subsequent phase retrieval provided the full 3D electron density of the virus with a full-period resolution of 125 nm10. This indicates that the Mimivirus is reproducible to at least this resolution.

Validation of the 3D reconstruction

In cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), data is routinely split prior to analysis and the analysis is performed in parallel on the two sets26. Our first method for validating the 3D reconstruction is an adaptation of this technique. The diffraction patterns are randomly split in two sets of equal size. The recovery of the 3D alignment is performed independently on the two sets using the same parameters but independent random starting points. Phase retrieval is also performed independently using the same parameters. The standard practice in the field is to repeat the reconstruction at least 100 times and the results are then averaged to average out effects of the random starting point4,27.

The EMC algorithm recovers the relative orientation of the particles from the diffracted data alone but the arbitrary rotation of the entire system can be different comparing the two resulting 3D electron density maps. In order to compare the two recovered electron densities we therefore have to rotate one of the two data sets to best match the other. This is done using brute force by interpolating one of the maps at a regular array corresponding to the tested rotation. To compare the two maps, the Pearson correlation coefficient is calculated. The rotation with the highest Pearson correlation is assumed to correspond to the proper relative orientation.

The two aligned electron density maps are then compared using the Fourier shell correlation (FSC)26, which provides a measure of the similarity as a function of resolution. The threshold for what is regarded as an acceptable fit ranges between 0.14 and 0.5 in cryo-EM literature28,29.

In X-ray crystallography some Bragg spots are usually excluded from the analysis and instead that information is used to verify the recovered expected strength of the respective Bragg spot30. Using the same idea, 10% of the diffraction patterns were selected to be used for validation only. In the EMC scheme these patterns are excluded from the analysis but are still compared to the recovered Fourier transform of the particle. The measure for determining whether the recovered model agrees with the excluded diffraction patterns is the likelihood function used internally in EMC.

The analogy with the Rfree value in crystallography should not be over emphasized. Bragg peaks are linearly independent parameters and ther is no suitable analogy in the continuous diffraction case. Furthermore, in the case described here, the process that is validated is that of pattern alignment and not phase retrieval. It is therefore natural to choose individual diffraction patterns as the information unit to exclude rather than i.e., individual pixels or regions of pixels.

These validation methods were previously described in ref. 10.

Usage Notes

Data was stored in the CXIDB25 data format which uses the HDF5 format. HDF5 files are readable in many computing environments including python using the h5py module and MATLAB using e.g., the h5read function. Convenient functions for accessing the CXIDB data file exist in the libspimage package for C and python31. For visualizing data the CXIDB file browser Owl (https://github.com/FilipeMaia/owl) is recommended.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Ekeberg, T et al. Single-shot diffraction data from the Mimivirus particle using an X-ray free-electron laser. Sci. Data 3:160060 doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.60 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Max Planck Society, the European Research Council, the Röntgen-Ångström Cluster, and Stiftelsen Olle Engkvist Byggmästare. Portions of this research were carried out at the Linac Coherent Light Source, a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the US Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. We are grateful to the scientific and technical staff of the LCLS for support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data Citations

- Ekeberg T. 2015. Coherent X-ray Imaging Data Bank. http://dx.doi.org/10.11577/1236752

References

- Emma P. et al. First lasing and operation of an ångström-wavelength free-electron laser. Nat. Photonics 4, 641–647 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Neutze R., Wouts R., van der Spoel D., Weckert E. & Hajdu J. Potential for biomolecular imaging with femtosecond X-ray pulses. Nature 406, 752–757 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman H. N. et al. Femtosecond diffractive imaging with a soft-X-ray free-electron laser. Nat. Phys 2, 839–843 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Seibert M. M. et al. Single mimivirus particles intercepted and imaged with an X-ray laser. Nature 470, 78–81 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh N.-T. D. & Elser V. Reconstruction algorithm for single-particle diffraction imaging experiments. Phys. Rev. E. Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys 80, 026705 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung R., Shneerson V., Saldin D. K. & Ourmazd A. Structure from fleeting illumination of faint spinning objects in flight. Nat. Phys 5, 64–67 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Galayda J. LCLS The First Experiments. Available at http://www.slac.stanford.edu/pubs/slacreports/reports03/slac-r-611.pdf (2003).

- Hantke M. F. et al. High-throughput imaging of heterogeneous cell organelles with an X-ray laser. Nat. Photonics 8, 943–949 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- van der Schot G. et al. Imaging single cells in a beam of live cyanobacteria with an X-ray laser. Nat. Commun 6, 5704 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekeberg T. et al. Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of the Giant Mimivirus Particle with an X-Ray Free-Electron Laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 098102 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raoult D. et al. The 1.2-megabase genome sequence of Mimivirus. Science 306, 1344–1350 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claverie J.-M. & Abergel C. Mimivirus and its virophage. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 49–66 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C. et al. Structural studies of the giant mimivirus. PLoS Biol. 7, e92 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C. et al. Cryo-electron microscopy of the giant Mimivirus. J. Mol. Biol. 353, 493–496 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne D. et al. The polyadenylation site of Mimivirus transcripts obeys a stringent ‘hairpin rule’. Genome Res. 19, 1233–1242 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePonte D. P. et al. Gas dynamic virtual nozzle for generation of microscopic droplet streams. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys 41, 195505 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Bogan M., Benner W. & Boutet S. Single particle X-ray diffractive imaging. Nano Lett. 8, 310–316 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostedt C. et al. Ultra-fast and ultra-intense X-ray sciences: first results from the Linac Coherent Light Source free-electron laser. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys 46, 164003 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Strüder L. et al. Large-format, high-speed, X-ray pnCCDs combined with electron and ion imaging spectrometers in a multipurpose chamber for experiments at 4th generation light sources. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers, Detect. Assoc. Equip 614, 483–496 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Yoon C. H. et al. Unsupervised classification of single-particle X-ray diffraction snapshots by spectral clustering. Opt. Express 19, 16542 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassemeyer S. et al. Femtosecond free-electron laser X-ray diffraction data sets for algorithm development. Opt. Express 20, 4149 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L. et al. Femtosecond electronic response of atoms to ultra-intense X-rays. Nature 466, 56–61 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucar L. et al. CASS—CFEL-ASG software suite. Comput. Phys. Commun. 183, 2207–2213 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Barty A. et al. Cheetah: software for high-throughput reduction and analysis of serial femtosecond X-ray diffraction data. J. Appl. Crystallogr 47, 1118–1131 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia F. R. N. C. The Coherent X-ray Imaging Data Bank. Nat. Methods 9, 854–855 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harauz G. & van Heel M. Exact filters for general geometry three dimensional reconstruction. Optik (Stuttg) 78, 146–156 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Chapman H. N. et al. High-resolution ab initio three-dimensional X-ray diffraction microscopy. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 23, 1179–1200 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal P. B. & Henderson R. Optimal Determination of Particle Orientation, Absolute Hand, and Contrast Loss in Single-particle Electron Cryomicroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 333, 721–745 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttcher B., Wynne S. & Crowther R. Determination of the fold of the core protein of hepatitis B virus by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature 386, 88–91 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A. Free R value: a novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature 355, 472 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia F. R. N. C., Ekeberg T., van der Spoel D. & Hajdu J. Hawk: the image reconstruction package for coherent X-ray diffractive imaging. J. Appl. Crystallogr 43, 1535–1539 (2010). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Ekeberg T. 2015. Coherent X-ray Imaging Data Bank. http://dx.doi.org/10.11577/1236752