ABSTRACT

Autophagy maintains cellular quality control by degrading organelles, and cytosolic proteins and their aggregates in lysosomes. Autophagy also degrades lipid droplets (LD) through a process termed lipophagy. During lipophagy, LD are sequestered within autophagosomes and degraded by lysosomal acid lipases to generate free fatty acids that are β-oxidized for energy. Lipophagy was discovered in hepatocytes, and since then has been shown to function in diverse cell types. Whether lipophagy degrades LD in the major fat storing cell—the adipocyte—remained unclear. We have found that blocking autophagy in brown adipose tissues (BAT) by deleting the autophagy gene Atg7 in BAT MYF5 (myogenic factor 5)-positive progenitors increases basal lipid content in BAT and decreases lipid utilization during cold exposure—indicating that lipophagy contributes to lipohomeostasis in the adipose tissue. Surprisingly, knocking out Atg7 in hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons also blocks lipophagy in BAT and liver suggesting that specific neurons within the central nervous system (CNS) exert telemetric control over lipophagy in BAT and liver.

KEYWORDS: adipose, autophagy, cold, lipophagy, POMC

Cold exposure and sympathetic stimulation promote adipose lipolysis. Since autophagy degrades LD via lipophagy, we asked whether cold exposure or treatment with sympathomimetic agents activates autophagy in adipocytes. To that purpose, mice were maintained at room temperature or exposed to cold (4°C for 1 h) following which their brown adipose tissues (BAT) were collected and subjected to autophagy analyses. Cold increases the expression of autophagy-related (Atg) and lysosomal genes, increases protein levels of ATG7, ATG12–ATG5 conjugate, BECN1, and WIPI2, and robustly increases autophagy flux in BAT. Replacing cold-exposed mice to room temperature rapidly normalizes autophagy flux to baseline levels demonstrating that cold activates autophagy. Since cold exposure leads to sympathetic activation, we asked whether exposing mice to the sympathomimetic agent isoproterenol is sufficient to activate autophagy in the absence of cold. Indeed, treating mice with isoproterenol results in the activation of autophagy in BAT indicating that cold-driven sympathetic activation triggers autophagy.

Since lipid oxidation in BAT helps maintain body temperature, and in light of our finding that cold activates autophagy, we asked whether autophagy serves to degrade LD during cold exposure. To address this question, we isolated LD fractions from BAT from control and cold-exposed mice and tested for the enrichment of the autophagosome marker LC3-II in LD. Indeed, cold exposure increases levels of LC3-II in BAT-derived LD, which we confirmed by immunofluorescence showing increased colocalization of LC3 and LAMP1 (marker of acidic organelles) with the neutral lipid dye BODIPY493/503 in BAT sections from cold-exposed mice. The requirement of autophagy for LD turnover was determined by testing the effect of loss of autophagy (by deleting Atg7) on cold-driven lipid utilization. Since MYF5-positive progenitors give rise to BAT, we knocked out Atg7 in BAT by crossing Atg7Flox/Flox mice with mice expressing Cre in MYF5-positive cells (MYF5-Atg7 KO). As anticipated, BAT from MYF5-Atg7 KO mice display increased basal lipid content, and KO BAT fails to mobilize LD when subjected to a cold challenge demonstrating that lipophagy actively contributes to lipohomeostasis in the adipose tissue.

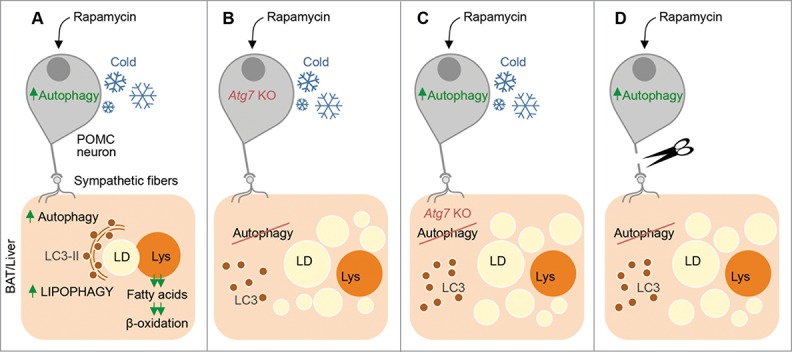

Strikingly, we observed that cold-induced autophagy in BAT and liver occurs in parallel with the induction of autophagy in hypothalamic neurons (Fig. 1A). Hypothalamic neurons regulate food intake and energy expenditure. Since we have previously shown that loss of autophagy in POMC neurons promotes adiposity, we hypothesized that autophagy in POMC neurons is required to mobilize lipid in peripheral tissues—possibly through lipophagy. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the effect of loss of POMC neuronal autophagy on: (i) autophagy flux, (ii) autophagic sequestration of LD, and (iii) lipid utilization—in BAT and liver. Surprisingly, POMC neuron-specific Atg7 KO mice display reduced autophagy and LD turnover in BAT and liver, decreased mitochondrial respiration in these organs, and failure to maintain body temperature during cold exposure (Fig. 1A and B). Conversely, activating hypothalamic autophagy via a single stereotaxic injection of rapamycin leads to activation of autophagy and increased lipid breakdown in BAT and liver (Fig. 1A). In fact, hypothalamic rapamycin administration increases tissue lipolysis in an autophagy-dependent mechanism since knocking out Atg7 in BAT or liver each blocks LD breakdown in response to rapamycin (Fig. 1C). These findings demonstrate that CNS autophagy governs peripheral lipophagy in a cell-nonautonomous manner akin to the recently elucidated cell-nonautonomous regulation of the unfolded protein response and heat shock response in C. elegans.

Figure 1.

Telemetric control of lipophagy in brown adipose tissue (BAT) and liver by autophagy in hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons. (A) Cold exposure or intra-hypothalamic rapamycin administration activates autophagy in POMC neurons in the CNS and in BAT and liver. In BAT and liver, autophagy sequesters lipid droplets (LDs) and degrades them in lysosomes (Lys). Lysosome-derived free fatty acids are β-oxidized for generation of energy and heat. (B) Mice lacking Atg7, and hence autophagy, in POMC neurons are unable to activate autophagy and break down LD in BAT and liver in response to cold or hypothalamic rapamycin administration. (C) Cold exposure or rapamycin administration increases BAT and liver lipolysis in an autophagy-dependent mechanism since knocking out Atg7 in BAT/liver or injecting lysosomal inhibitors intra-peritoneally blocks tissue-intrinsic LD break down. (D) POMC neuronal autophagy regulates peripheral lipophagy through neuronal connections since denervating BAT blocks autophagy and lipid utilization in response to intra-hypothalamic rapamycin—indicating that CNS-to-peripheral autophagy networks regulate lipid utilization.

To determine how hypothalamic autophagy regulates peripheral lipophagy, we tested whether direct neuronal connections allow CNS autophagy to “talk” to peripheral lipophagy. Accordingly, we tested the ability of intra-hypothalamic rapamycin administration to activate autophagy in denervated BAT pads. Interestingly, denervating BAT renders it completely unresponsive to intra-hypothalamic rapamycin in terms of activation of autophagy and lipolysis indicating that direct neuronal links connect CNS autophagy to peripheral autophagy and lipolysis (Fig. 1D). Our results demonstrate that active autophagy in POMC neurons is required for these neurons to exert telemetric control over autophagic lipid consumption in BAT and liver. Since POMC neuronal autophagy decreases with age, these findings suggest that age-associated changes in POMC neuronal autophagy could lead to loss of “autophagy tone” in the periphery and disrupt lipohomeostasis. How sympathetic nerve activity drives lipophagy remains unknown. Whether autophagy activation requires suppression of MTOR or whether cold-driven autophagy occurs in an MTOR-independent mechanism remains to be seen. While activating autophagy in the CNS appears to be an attractive approach against age-associated neurodegeneration, it may also prevent the age-associated metabolic decline by “fixing” the periphery.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by AG043517 (RS), Ellison Medical Foundation new scholar award (RS), and DK020541 (Einstein Diabetes Research Center). The authors have no competing financial interests to declare.