Abstract

Background: Workforce motivation and retention is important for the functionality and quality of service delivery in health systems of developing countries. Despite huge primary healthcare (PHC) infrastructure, Pakistan’s health indicators are not impressive; mainly because of under-utilization of facilities and low patient satisfaction. One of the major underlying issues is staff absenteeism. The study aimed to identify factors affecting retention and motivation of doctors working in PHC facilities of Pakistan.

Methods: An exploratory study was conducted in a rural district in Khyber Puktunkhwa (KP) province, in Pakistan. A conceptual framework was developed comprising of three organizational, individual, and external environmental factors. Qualitative research methods comprising of semi-structured interviews with doctors working in basic health units (BHUs) and in-depth interviews with district and provincial government health managers were used. Document review of postings, rules of business and policy actions was also conducted. Triangulation of findings was carried out to arrive at the final synthesis.

Results: Inadequate remuneration, unreasonable facilities at residence, poor work environment, political interference, inadequate supplies and medical facilities contributed to lack of motivation among both male and female doctors. The physicians accepted government jobs in BHUs with a belief that these jobs were more secure, with convenient working hours. Male physicians seemed to be more motivated because they faced less challenges than their female counterparts in BHUs especially during relocations. Overall, the organizational factors emerged as the most significant whereby human resource policy, career growth structure, performance appraisal and monetary benefits played an important role. Gender and marital status of female doctors was regarded as most important individual factor affecting retention and motivation of female doctors in BHUs.

Conclusion: Inadequate remuneration, unreasonable facilities at residence, poor work environment, political interference, inadequate supplies, and medical facilities contributed to lack of motivation in physicians in our study. Our study advocates that by addressing the retention and motivation challenges, service delivery can be made more responsive to the patients and communities in Pakistan and other similar settings.

Keywords: Motivation, Retention, Physicians, Rural Postings, Qualitative

Background

Adequate health workforce development is one of the key functions of an efficient and well-functioning health system.1 Human resource for health (HRH) management comprises of well-trained, motivated and equitably distributed health work force.2 Health sector is a labor intense industry3 and HRH in developing countries is frequently underpaid4 which often leads to their lack of motivation to deliver function. Motivation is defined as “the willingness to exert and maintain an effort towards organizational goals.”5 Workforce motivation is an important predictor of health sector performance, efficiency, quality of service, and equity.6 Achievement of health-related millennium development goals, previously, and sustainable development goals, especially goal 3, are strongly linked with improvement of HRH situation in developing countries.3 While studies assess HRH strengths there is less in-depth work on motivational factors affecting retention of healthcare staff and more so, trained physicians in developing countries including Pakistan. Most of such research has originated from Europe, North America, and African region but evidence from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) of Asia is limited.7 Staff availability is critical to better performance and health-related outcomes at health facilities in developing countries. Health facilities manned by skilled, committed and satisfied staff, perform to deliver high quality services, far better than those which have staff shortages.8,9 Lack of motivation among healthcare staff affects their satisfaction and retention and results in their migration to the urban health facilities or to affluent countries. Security concerns in conflict hit countries,10 lack of adequate compensation packages11 and limited progress in career pathway12 are important reasons for the physicians to migrate to urban areas or to western countries.

Several approaches have been used to understand the staff motivation to the work in health facilities in developed countries. Most, however, focus on quality of work life and show its inverse relation with staff turnover.13 Other studies have used paradigms where individual factors have been studied in detail. These studies show that a set of financial and non-financial factors affect motivation of health staff at primary healthcare (PHC) facilities. Work compensation ensures professional survival and security of individuals14; remuneration, appropriate with the relevant market, ensures staff retention in developing countries.15 However, financial incentives are important for motivation of workforce but are not the only factor responsible for the lack of motivation. Motivation results from a complex relationship of various determinants and context specific processes.15 Therefore, other factors that affect staff motivation have been related with discriminatory behavior of organizations against health staff of urban versus rural areas.16 This study aimed to identify factors affecting retention and motivation of physicians working in basic health units (BHUs) and prioritize important factors for the basis of giving recommendations for strategies to improve retention and motivation of physicians in Pakistan and particularly in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). The objectives included identification of individual, facility level and organizational factors which affect retention and motivation of physicians in the rural BHUs of KP.

HRH Situation in Pakistan

Setting

Pakistan spends about 2.1% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health17; of which 83% is private. Ninety-eight percent of private spending is through out-of-pocket payments at the level of service utilization.2 Health status of Pakistani population presents a grim picture. Maternal mortality is 276 deaths per 100000 live births and infant and under five child mortality is 74 and 89 deaths per 1000 live births, respectively.18 Pakistan has a well-developed PHC infrastructure19 which includes 552 rural health centers (RHCs), 5290 BHUs and 4554 dispensaries in public sector. The country has a physician to population ratio of 0.473 to 100020; and is much less in rural areas of Pakistan given that 60% of medical graduates have the ambition to migrate out of the country for better opportunities.21 More than 1100 physicians migrated out of the country out of an estimated 5400 graduates in 200620 and such brain drain is projected to further escalate in future. Recurrent cost on HRH in PHC account for the 80% of total cost of running PHC services in Pakistan.22 The Abbottabad district in the province of KP, where we conducted our research, had population of 928000 of which 81% was rural in 2009. The district had one teaching hospital, 1 district headquarter hospital (DHH), 4 RHC (each serving a population of 100000), 53 BHUs (each serving a population of 25000). Out of the 37 physician posts, only 16 (43.2%) were filled.23

BHUs are first level care facilities (FLCF) in Pakistan. Political interference,24 pilferage, poor inventorying and storage practices for drugs, lack of capacity in district health offices in terms of human and financial resources are some of the factors of poor quality of healthcare services in the country.25 Lack of workforce motivation has been identified as one of the important factors for lower utilization of BHUs.26 Staff absenteeism is common, postings in health facilities are often linked to favoritism26 and physicians are frequently transferred or “seconded” to healthcare facilities in the cities.27 The recruitment and appointment is highly influenced by political persons and successive new governments abolish or ignore successful health policies and programs initiated by the previous governments.28,29 However, the situation is said to have improved in Pakistan since 2007 when the country introduced a national program, known as the People’s Primary Healthcare Initiative (PPHI). This program was based on the success from small scale reforms in the district of Punjab. Under this initiative about 20 BHUs were made functional in the province of KP and many more were repaired and renovated and many posts for medical and auxiliary staff were filled. Also, at the time of this study, more than 60% of medical officers in the province of KP worked under a contract with PPHI rather than as permanent employees of health department and newly recruited physicians were offered better packages.30

Currently the province is going through a number of reforms at the PHC as well as at secondary and tertiary healthcare facility levels. Health Reforms Act 2015 by the current democratic government by the party which came into power for the first time in 2013 promise to implement reforms to appoint civil servants as the heads of the institutions working under the health department. The government is also planning to run the BHUs under a public private partnership system to replace the current mechanism of contacting out to the PPHI which is said to have suffered many challenges and politicization.31 The new program is expected to uplift the functions and services of the PHC facilities and may contribute toward improved motivation and retention of physicians.

Methods

Study Design

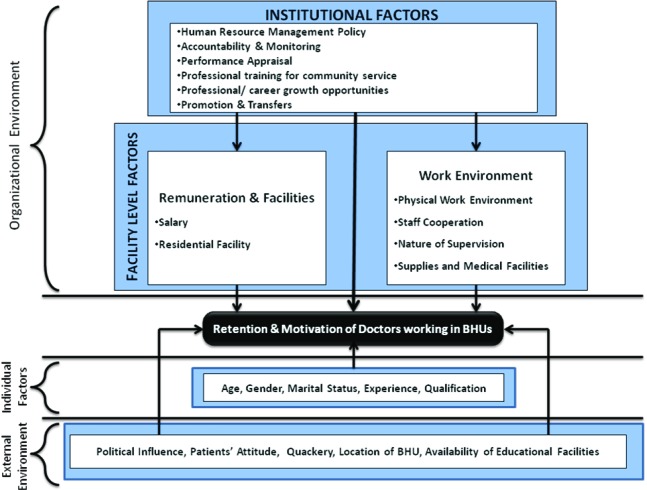

An exploratory qualitative research approach was used to address our research objectives. Rationale for using qualitative methods in this study was to understand complexity of issue of HRH motivation which is affected by multiple factors such as health system, individuals’ experiences; and context of the health facility, both geographic and social, and the inter-relation of these factors. Franco et al, identifies three broad categories of determinants motivation in employees; namely the individual, organizational, and cultural. They state that “motivation is a transactional process: it depends upon the fit between the individual and the organizational context within which they work, and the broader societal context.”6 Emerging themes and their interrelationships were merged into the conceptual framework, adapted from Franco et al, explaining physicians’ retention and motivation (Figure). The conceptual framework proposes three levels of factors, including organizational environment, individual, and workplace environment related factors, which may affect retention and motivation of physicians in BHUs.

Figure.

Conceptual Framework (Adapted from Franco et al6).

Study Participants

The study was conducted in Abbottabad district of KP province of Pakistan in 2009. Study population included physicians of all BHUs of the district and key informants at both district and provincial level. The district had 16 physicians posted at BHUs at the time of the study and all of them were interviewed in-depth. Six key informants each from district and province levels (Table 1) were also interviewed. The physicians from BHUs had bachelor of medicine and bachelor of surgery, equivalent of doctor of medicine (MD), as highest qualification. All of them were married and 2 were females. The mean age of physicians was 38 years; they had mean total years of experience of 9.83 years and mean years of experience of working in a BHU of 2.53 years. All the six key managers or administrators from the Abbottabad district were males and over the age of 40 years. However, from the province, 1 of the 6 participants was a female.

Table 1. Profile of the Participants .

| Participants From District Level | Participants From Provincial Level |

| 16 Medical officers | CPO |

| EDOH | Chief of HSRU |

| Deputy District Officer (Health) | DG Health, KP |

| A member of a NGO | Coordinator HSRU |

| Chief executive of a teaching hospital in district Abbottabad | Representative of private healthcare sector |

| District nazim (Mayor) Abbottabad | Pakistan medical association provincial representative |

| Expanded program of immunization coordinator | |

Abbreviations: EDOH, Executive District Officer Health; NGO, non-governmental organization; CPO, Chief Planning Officer; HSRU, health sector reforms unit; DG, Director General; KP, Khyber Puktunkhwa.

In-depth interviews were conducted with these participants using a semi-structured field guide consisting of open ended questions. The field guide was pretested on three physicians working in BHUs of the neighboring district of Mansehra who were not part of the study. Interviews were tape-recorded with consent from participants; however, notes were taken if the participants did not consent to the tape recording. Each interview was conducted in Urdu, the national language of Pakistan and lasted for 40 to 60 minutes. The P.I. did all interviews himself while a note taker was available during interviews. Official documents and reports related to human resource management (HRM) in health department of KP were also reviewed to explore the current human resource strategies relevant to motivation and retention of physicians in the province. KP Civil Servants Act of 1973 (CSA) and performance evaluation report (PER) was suggested as main documents for review by the key informants. The PER format form is used for performance appraisal of government servants serving under Basic Pay Scale (BPS) 17 and 18.

Participation in this study was voluntary and a prior written and informed consent was obtained from all the study participants. Participants were assured about the privacy and confidentiality of their data. Permission to carry out the study was obtained from the EDOH of district Abbottabad.

Coding and Synthesis of Results

Every interview was transcribed into Urdu and translated into English. Data collection, note-taking, coding and memo writing took place simultaneously. Memo writing and coding was used in the organization of emerging categories and their interrelationship. After each interview session, key words of the interviews were noted using Microsoft Project 2007 and were used afterwards in the formation of themes. Comparison was made by checking notes against the tape recordings in order to identify useful themes. The transcribed interviews were supplemented with the notes taken during the interviews. Coding was done manually by using Microsoft office highlighting options. Matching color codes from all the interviews were synthesized to form different themes. After coding and memo writing the themes were made and interrelated under broader nodes such as; reasons to opting for jobs in BHUs, individual factors, remuneration, facilities and larger organizational factors. Finally the findings from interviews with physicians, key informants and the document review were triangulated. Key statements from the participants have been used to support findings and these have been mentioned as quotes.

Results

Individual/Personal Factors

The main question asked was “why did you opt for government service?” and the participants were further probed regarding reasons for opting for positions in BHUs.

Gender of the Physicians

While it was much easier for male physicians to relocate to the BHUs, this was challenging for their female counterparts. Females found it difficult to relocate to the rural posts because of cultural reasons - their families feared for their security commuting to work was more favorable than to live in the residence attached with the BHUs for female physicians. However, many female physicians chose BHU jobs because of convenient opening hours of the facilities. A lady doctor said: “Duty hours in the BHU I work are from 8 am to 2 pm and there is no evening or night duty; which is the reason I opted for the job.” One of the respondents mentioned, “Female physicians usually do not like to work in BHUs. The reason may be the lack of security; they can’t live alone.” We explored the CSA of 1973 for the gender-related guidance and clauses but it had no recommendations to address such issues.

Marital Status

Married physicians, especially female, were less motivated in BHUs than the single. Physicians believed that relocation to BHUs disrupted their personal lives as their other responsibilities remain unattended. A lady doctor mentioned that her husband worked in the city and it was impossible for her family to relocate to the BHU. As most physicians in the study lived in towns, they believed they wasted time in commuting to and from BHUs. Therefore, they preferred to reside near the BHU to avoid the travel time. All physicians interviewed were married with children. As thus, they believed that they needed time to parent their children. However, they considered that education opportunities for children were insufficient in rural areas and the BHU residences were not satisfactory, therefore, they had decided not relocate to their workplaces.

Nature of the Job

Participants found their jobs flexible and manageable since they were not called for any emergency. Physicians also believed that having a public sector position ensured job security for the rest of their careers, therefore, they chose BHU jobs. Others considered BHU positions as the only option for a fresh graduate. They also regarded these jobs as an entry point to enter public sector. The physicians mentioned that the communities they belonged to, traditionally, admired public servants. They also believed that a few physicians joined BHUs with a passion to serve their own communities.

Absenteeism

All the key informants at district and provincial levels acknowledged that retention and motivation of physicians was reflected from their frequently being absent from health facilities. A key informant said: “… 30% posts of physicians in the province are filled and most of them do not attend to their duties regularly.” We found that younger physicians were more motivated than the senior ones. Also, the physicians with higher qualifications were less likely to stay longer in BHUs, as compared to those with only the basic medical degree; because the former frequently joined residency positions in the larger hospitals or migrate abroad.

Residence and Other Facilities for Physicians at Basic Health Units

Medical officers, relocating for jobs in BHUs, are usually provided a residence adjacent to most BHUs in Pakistan. The participants agreed that these houses were uninhabitable because they were inadequately maintained and most lacked water and electricity connections. A female doctor said: “I joined BHU because I hoped to get a house to live; but the BHU residence is not worth living, so I may soon have to leave.” Key informants at district level agreed that living conditions of physicians in rural BHUs were not satisfactory. District officials believed that repair and renovation of physicians’ residences required the requests to be approved for funds and permissions; a process that could take several months or even years. Also, in case of relocation to rural areas physicians struggled to find quality schooling facilities for their children. Commuting to and from BHUs was difficult not only for female but for male physicians because of lack of decent public transport and roads were not properly developed. A female doctor said: “Who will be willing to work in a BHU which doesn’t even have road access? I have to walk two kilometers daily to reach the main road leading to the BHU where I work.”

Workplace Level Factors Affecting Retention and Motivation of Physicians

Work Environment

Participants were satisfied with physical environment in BHUs including the outpatient department (OPD) room, furniture and equipment. They believed that attitude of the staff in BHUs was important for their motivation and that their staff was cooperative. However, other participants said that the staff was unsupportive and apprehensive of physicians because many of the auxiliary staff practiced quackery in the communities around BHUs; often without a license to practice. Though these factors were beyond the control of physicians, they often had to face angry patients. Participants mentioned that recognition of their work by the supervisors was encouraging.

Political Interference

The local community and politically powerful persons frequently interfered in the affairs of BHUs which affected appointments and transfers of staff. The physicians felt that this was a form of injustice to their colleagues. This resulted in absenteeism by the physicians transfers. One doctor stated that “… Every patient is equal to us and we cannot give preference to a relative of a member of any political party. They try to influence us in several ways or they often threaten us to get us transferred to a remote BHU.”

Over-Arching Organizational Factors

Remuneration

Physicians were not satisfied with their remuneration packages. They considered their salaries to be way less compared to services provided and their families’ needs. They particularly believed that they earned far less than same level physicians in secondary or tertiary care hospitals. A female doctor said: “Our main purpose (to work in BHUs) is salary; which does not match with our qualifications. Currently I work in a BHU which is near my city; but if I am transferred to a BHU in a rural area, I may have to resign unless an attractive salary is offered.” Three key informants at provincial level differed and believed that revision of physicians’ salaries in the past could not win dedication of physicians to their work. However, physicians perceived that such increments in remuneration could hardly match rising inflation rates and cost of living in the country and the services they provided in the BHUs. Physicians said that they were not offered any significant incentives to work in hardship areas (the rural areas located far away from cities with limited amenities of life).

Professional Growth and Training

The participants in our study had very limited continuous professional development (CPD) opportunities. However, some training events on immunization, disease early warning system and tuberculosis control were offered to them which were mostly organized, either, by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or through national programs. A participant recommended that CPD opportunities need to be provided to them while on job, as they are offered in higher level health facilities: “I have learnt nothing new in my two year job in the BHU; larger hospitals provide continuous medical education session; which is necessary for the professional growth of physicians.” Another participant noted the inability of physicians’ professional progress while in BHUs and that as they grew older, they lost interest in learning or keeping updated with new technologies and innovations in medicine.

Promotions and Transfers

The physicians were dissatisfied with overall process of promotions and transfers in the public health sector. They believed that without links with any influential person or health officials, it was hard for them to be appointed or transferred to a desired location. Some key informants at district and provincial health departments did not agree that the transfers, postings or promotions took place with the help of politicians or other influential persons. They also denied that nepotism or any personal favors affected the progress of physicians’ careers. The views of key informants about transfers and promotions were aligned with CSA. Terms and conditions of service section contained rules for promotion, transfers and postings. Section 10 stated that every civil servant may serve within or outside the province. However, section 9 stated that a prescribed “minimum qualification” was required for promotions to positions other than the cadres for which the civil servants were recruited. However, the physicians believed that such rules were often relaxed or bypassed for the influential physicians.

Supplies and Medical Facilities

Shortage of medicines and other essential commodities in the BHUs annoyed patients. Such shortages occurred as a result of poor planning, unnecessarily time consuming procurement procedures and other bottlenecks in supply chain management. A key informant from the district agreed that the irregular supply of essential commodities to the health facilities was a challenge under which physicians had to work. He believed that there were monetary constraints which caused delay in the supply chain of essential commodities. He said, “…in government sector the EDO gets roughly 2 million rupees a year ($US 20000) for the medicine to be supplied in the district and it is impossible to meet the healthcare needs of people with this meager budget.”

Performance Appraisal and Job Descriptions

We found that participants knew little about the process of their performance appraisals; younger physicians were not aware that the PER even existed and that their promotions should be based on the report. They were, though, familiar with the annual confidential report (ACR). Provincial officials said that monitoring and evaluation of physicians was almost not happening in the province and performance appraisal was an inefficient process. Two provincial key informants agreed that a proper reward mechanism in the public health sector was almost absent. Moreover, lack of performance appraisals and proper supervision of the physicians was attributed to nonexistent job descriptions. A doctor said “…if the performance reports are not analyzed properly, then no actions are expected. The performance appraisal currently in practice must be updated. Job descriptions do not exist in health department; the older version of the documents needs to be updated.”

Human Resource Management Strategies

We asked the key informants at provincial level if any document was available which consisted of HRM policy and strategy to improve the retention and motivation of physicians at PHC facilities in the province. All the participants agreed that the CSA of 1973 still was considered the guiding document; however, no other specific HRM policy document was available. The CSA has guidelines for the appointment, probation, probation confirmation, promotion, posting and transfers, termination of service, disciplinary action, retirement and incentives. However, the physicians believed that such a generic document was not sufficient for HRM in health facilities. They argued that the older documents needed to be revised to include the solutions to the current work place problems faced by healthcare workforce in the province.

Priority Themes

Table 2 gives an overview of the most important factors for the retention and motivation of physicians in the context of rural Pakistan.

Table 2. Priority Factors Which Affecting Motivation and Retention of Physicians .

| Responsesa | |

| Individual factors | |

| Lack of basic facilities for physicians and their families | ++++++++++ |

| Remoteness and lack of education facilities | +++++++++ |

| Workplace related factors | |

| Nature of work | ++++++++ |

| Respect | ++++ |

| Over-arching organizational factors | |

| Remuneration | ++++++++++++++ |

| Job security | +++++++++++ |

| Supplies and medical facilities | +++++++++ |

| Lack of promotions and politically influenced transfers | ++++ |

| Trainings and learning opportunities | ++ |

a Plus sign represents a participant.

Remuneration, lack of essential facilities such as decent residence or education for children in the rural areas were the most frequent and pressing factors. Lack of medicines and equipment in the health facilities, political interference in transfers, posting and promotions were priority job related factors. Job security attracted the physicians to the rural positions, respect associated with public sector jobs and training opportunities for physicians played a significant role in convincing physicians to be motivated to stay in their jobs.

Discussion

An understanding of the factors influencing the motivation and retention is essential for the development and implementation of the policies to encourage health workers to relocate to and stay in PHC postings.32 The World Health Organization (WHO) in a 2010 report, recommended educational, regulatory, financial, personal and professional support for the physicians in the countries with HRH shortage. The report also indicated that countries needed to prioritize these recommendations based on their relevance, acceptability, affordability, effectiveness and impact.33 Results from this study endorse these recommendations by identifying financial incentives or salary revisions, improvement of living and work conditions of the physicians and provision of sufficient career development opportunities would help in the physicians’ motivation and retention. However, interventions such as enforcement of regulatory policies, including mandatory postings in rural areas, and their relation to the retention and motivation of physicians were not discussed by our study participants. This study has identified and prioritized these factors under similar parameters of suitability of their implementation with possible revision of the HRH policies in Pakistan (Table 2).

While other studies have generally focused on organizational context and physicians’ individual attributes,13,14 this study explored beyond this paradigm and identified the linkages between these and other attributes to develop a conceptual framework that would form basis for further research. In addition, the study also identified factors around organizational and external environment by focusing on the three tiers of the system namely, service providers (physicians), district level management and provincial and policy level participants. Overall, dissatisfaction with one’s job affects quality of work produced by the healthcare workers.13 Study findings are discussed under the individual factors which form the first, workplace related factors the second and overarching organizational factors the third layer of the framework (Figure).

Lack of educational and housing facilities close to health facilities demotivated physicians in this sample as they believed that relocating to the rural postings would make it challenging for their families to adapt to rural environment. Our results are consistent with studies that showed that for physicians to work in rural areas their living environment needed improvement. A reasonably decent residential facility provided by the government and a nearby educational facility for children of the healthcare providers and a safe and secure are considered important factors in physicians’ motivation to work in rural areas.34,35 It was found that gender was a strong influencing factor for the retention and motivation of physicians in BHUs and female health workers often feel challenged due to their responsibilities related to job and of raising their families. Female physicians were often not able to continue with their rural jobs for longer durations. This was because it was inconvenient to travel to the rural health facilities as most of them resided in cities.36 Relocation to rural posts was even more difficulty for the female physicians. Many also experienced cultural restrictions and taboos to work in communities other than their own.37

Most PHC facilities did not run round the clock and only few strategically selected ones provided maternal and child services during the night time where mostly female nurses, midwives, lady health visitors, and physicians provide services. As the physicians in our study were not required to perform night duties, opening hours suited them; which was a motivating factor for most of them. Evidence suggested that physicians would most likely be motivated and continue jobs if they find their duty hours convenient and flexible. On the contrary frequent shift work is related with stress which results from lack of satisfaction and high job turnover among healthcare providers.36,38

Respect given to physicians by the patients motivated physicians in this study. A healthy doctor-patient relationship was necessary and of paramount importance to the satisfaction of physicians.39 On the other hand, a lack of respect at work place harbored dissatisfaction and demotivation which eventually led towards negative impact on the part of physicians to impart their services with dedication and sincerity. This often reflected in their regular absenteeism from work and thoughts about changing jobs.9

Workplace factors such as inadequate remuneration contributed significantly to the physicians’ motivation to their work in our study. Physicians were generally dissatisfied with overall remuneration packages in Pakistan36; which was an important reason for them to change jobs, work in larger hospitals which would pay them better or migrate abroad, leaving rural health facilities under-staffed. Evidence from other Asian countries also shows that motivated physicians were more satisfied and motivated if they received better remuneration packages and other benefits in return for their services.34,40,41 Insufficiently low packages are consistently cited as one of the most important causes of dissatisfaction and lack of motivation among healthcare workers especially physicians.39

Lack of organizational oversight for employees was important factor for lack of motivation among physicians in this study. Lack of performance checks, absence of a career progression pathway for those posted in PHC facilities, political leverage to secure choice postings, allowance of private practice to government physicians resulting in neglect of government PHC duties, and lack of salary benefits tiered to hard area postings were some of the key organizational factors identified. Transparency in promotions in Tanzania42 was linked with better satisfied health workers. Results from this study were consistent with studies from developing countries like Malawi43 and Ghana,44 which also explained the demotivation among physicians as an effect of lack of sufficient professional and career growth opportunities at their jobs.

The notion of ‘job security’ was also a reason for staff absenteeism and frequent transfers out of rural districts, as seen in this study. However, evidence from India shows that job security was an important determining factor of satisfaction and motivation among physicians.40 As public sector jobs are considered highly secure because of the old civil servant act, favoring public sector employees, the physicians also consider their jobs highly secure. However, this gives them a sense of freedom and diminished accountability while on the job. In addition to this, accountability checks of staff presence and performance re generally conspicuously absent in Pakistan’s PHC systems and there is less evidence on the effectiveness of accountability checks and performance-based payments on physicians’ retention in rural areas.

Shortage of medicines is a source of annoyance and anger among patients which in turn can affect physicians’ motivation. Evidence suggests that health workers perform better45 when essential commodities and equipment are availed to them. This is because a completely equipped health facility and staff is necessary for comprehensive service delivery and patient care in healthcare setting. Patients are lease satisfied if they are not provided essential care at their designated health facility which challenges a doctor-patient relation and affects, negatively, the motivation in physicians.46 In Pakistan, healthcare staff has been consistently shown to be dissatisfied as the health system struggles to cope with the challenge of catering to the needs of the growing number of patients and one of the reason has been cited to be inadequate supplies available to health staff.47

Inclusion and analysis of perspectives of both physicians as well as health managers from district and provincial levels was strength of this study. However, this study did not include evidence from other districts that were under a PHC management reform. Under the new reform initiative PHC facilities have been outsourced for NGO management with physicians hired against vacant posts on higher salaries and on contractual rather than permanent contracts. The effectiveness of this approach on doctor motivation and retention in rural posts and comparison with the government managed PHC system would be valuable for future research.

Conclusion

Retention and motivation of physicians in rural PHC facilities is a challenge in Pakistan, as well as in other LMICs. A pragmatic and institutionally embedded human resource strategy is needed to retain physicians at PHC facilities responding to contextual challenges, rather than one off measures. Individual factors of gender and over-arching institutional issues are the most salient in affecting physicians’ retention in rural postings. These call for revisiting the number physicians needed in rural posts, task shifting from female physicians to other frontline staff, introducing a mix of incentives and performance checks for rural postings, and building career progression with PHC postings.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Dr. Babar Tasneem Shaikh for his help in the study. We are also grateful to the health department of the KP province, Pakistan for their cooperation to conduct this study.

Ethical issues

The study was approved by the ethical review committee of Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan (1253-CHS/ERC-09).

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SMS designed the study, collected and analyzed the findings under supervision of SZ. JA, SZ, and SUR synthesized the study into manuscript format and added further literature. SMS reviewed the manuscript.

Authors’ affiliations

1Relief International, Gaziantep, Turkey. 2Department of Community Health Sciences and Women and Child Health Division, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan. 3Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Arabian Gulf University, Manama, Bahrain. 4UNICEF, Quetta, Pakistan.

Key messages

Implications for policy makers

Inclusion of actions for motivation and retention of physicians at primary healthcare (PHC) facilities in the human resource for health (HRH) strategy of the province;

Improvement of basic facilities for physicians and their families including transport and educational facilities for their children;

Revision of remuneration packages, provision of necessary equipment and medicine in the health facilities;

Removal of any political interferences in the affairs of the health facilities;

Promotions of physicians in PHC facilities need to be based on transparent appraisals and evaluations;

Non-politically influenced transfers and postings in PHC facilities;

Adequate trainings and continuous learning opportunities for the physicians.

Implications for public

Policies for human resource for health (HRH) need to be participatory and must include public perspectives. Communities are the end users of the health services and health staff motivation and commitment to their jobs affects the way they serve the patients and their families. Communities can be included to participate in the development of satisfactory work place and living environment for the health providers so that they are made part of the very communities which they serve. They can help remove political interferences over the functions of health system so that the health system works as a free and relatively independent entity.

Citation: Shah SM, Zaidi S, Ahmed J, Rehman SU. Motivation and retention of physicians in primary healthcare facilities: a qualitative study from Abbottabad, Pakistan. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5(8):467–475. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2016.38

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). The World Health Report 2000: Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva: WHO; 2000.

- 2. World Bank. Health System and Financing: Human Resource. http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTHEALTHNUTRITIONANDPOPULATION/EXTHSD/0,,contentMDK:20190576~menuPK:2389336~pagePK:210058~piPK:210062~theSitePK:376793,00.html. Accessed February 3, 2015. Published 2008.

- 3. World Health Organization (WHO). The World Health Report 2006: Working together for health. Geneva: WHO; 2006.

- 4.Van Lerberghe W, Conceicao C, Van Damme W, Ferrinho P. When staff is underpaid: dealing with the individual coping strategies of health personnel. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(7):581–584. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathauer I, Imhoff I. Health worker motivation in Africa: the role of non-financial incentives and human resource management tools. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4:24. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-4-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franco LM, Bennett S, Kanfer R, Stubblebine P. Determinants and consequences of health worker motivation in hospitals in Jordan and Georgia. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(2):343–355. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Exworthy M. Policy to tackle the social determinants of health: using conceptual models to understand the policy process. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23(5):318–327. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belita A, Mbindyo P, English M. Absenteeism amongst health workers--developing a typology to support empiric work in low-income countries and characterizing reported associations. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:34. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajbhandary S, Basu K. Working conditions of nurses and absenteeism: is there a relationship? An empirical analysis using National Survey of the Work and Health of Nurses. Health Policy. 2010;97(2-3):152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Khalisi N. The Iraqi medical brain drain: a cross-sectional study. Int J Health Serv. 2013;43(2):363–378. doi: 10.2190/HS.43.2.j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawkes M, Kolenko M, Shockness M, Diwaker K. Nursing brain drain from India. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serour GI. Healthcare workers and the brain drain. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;106(2):175–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosadeghrad AM. Quality of working life: an antecedent to employee turnover intention. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2013;1(1):43–50. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2013.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fritzen SA. Strategic management of the health workforce in developing countries: what have we learned? Hum Resour Health. 2007;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Küpers W. A Phenomenology of embodied passion and the demotivational realities of organisations. Institute for Leadership and HR-Management, University St. Gallen, Switzerland; 2001.

- 16.Hou J, Ke Y. Addressing the shortage of health professionals in rural China: issues and progress: Comment on “Have health human resources become more equal between rural and urban areas after the new reform?”. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(5):327–328. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haq Z, Iqbal Z, Rahman A. Job stress among community health workers: a multi-method study from Pakistan. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2008;2(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Institute of Population Studies Pakistan. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2012-13. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR290/FR290.pdf.

- 19. Nishter S. Restructuring Basic Health Units – mandatory safeguards. http://www.heartfile.org/viewpoint-5-restructuring-basic-health-units-mandatory-safeguards/. Accessed April 15 , 2015. Published 2006.

- 20.Frey PM, Mean M, Limacher A. et al. Physical activity and risk of bleeding in elderly patients taking anticoagulants. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(2):197–205. doi: 10.1111/jth.12793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caviezel S, Dratva J, Schaffner E. et al. Carotid Stiffness and Physical Activity in Elderly--A Short Report of the SAPALDIA 3 Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green A, Ali B, Naeem A, Vassall A. Using costing as a district planning and management tool in Balochistan, Pakistan. Health Policy Plan. 2001;16(2):180–186. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Asian Development Bank, World Bank. Pakistan 2005 Earthquake: Preliminary Damage and Needs Assessment. Islamabad; 2005.

- 24.Collins CD, Omar M, Hurst K. Staff transfer and management in the government health sector in Balochistan, Pakistan: problems and context. Public Administration and Development. 2000;20(3):207–220. doi: 10.1002/1099-162x(200008)20:3<207::aid-pad126>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pappas G, Ghaffar A, Masud T, Hyder A, Siddiqi S. Governance and health sector development: a case study of Pakistan. Internet Science Publications. 2008;7(1):12487. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willis-Shattuck M, Bidwell P, Thomas S, Wyness L, Blaauw D, Ditlopo P. Motivation and retention of health workers in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:247. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Khan IA. Political Economy of Primary Healthcare Provision in Pakistan. http://tehqiq.googlepages.com/PoliticalEconomyofPHCinPakistanVer3..pdf. Accessed May 2, 2015. Published 2009.

- 28.Khan MM, Van den Heuvel W. The impact of political context upon the health policy process in Pakistan. Public Health. 2007;121(4):278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sengooba F, Rahman SA, Hongoro C. et al. Health sector reforms and human resources for health in Uganda and Bangladesh: mechanisms of effect. Hum Resour Health. 2007;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Facility TR. Third-Party Evaluation of the PPHI in Pakistan Findings, Conclusions and Recommendations. Unpublished document, 2010.

- 31. Bureau Report. Basic health units being outsourced in KP. Daily Dawn. November 10, 2015. http://www.dawn.com/news/1218720.

- 32.Dolea C, Stormont L, Braichet JM. Evaluated strategies to increase attraction and retention of health workers in remote and rural areas. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(5):379–385. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.070607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. World Health Organization (WHO). Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention: Global policy recommendations. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [PubMed]

- 34.Rao KD, Ryan M, Shroff Z, Vujicic M, Ramani S, Berman P. Rural clinician scarcity and job preferences of doctors and nurses in India: a discrete choice experiment. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Honda A, Vio F. Incentives for non-physician health professionals to work in the rural and remote areas of Mozambique--a discrete choice experiment for eliciting job preferences. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:23. doi: 10.1186/s12960-015-0015-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malik AA, Yamamoto SS, Souares A, Malik Z, Sauerborn R. Motivational determinants among physicians in Lahore, Pakistan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:201. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Attanapola CT. Changing gender roles and health impacts among female workers in export-processing industries in Sri Lanka. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(11):2301–2312. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahman SM, Ali NA, Jennings L. et al. Factors affecting recruitment and retention of community health workers in a newborn care intervention in Bangladesh. Hum Resour Health. 2010;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang YX, Kaplar Z, L YT. AME survey-003 A1-part 2: the motivation factors of medical doctors in China. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2015;5(6):917–924. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2015.12.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Purohit B, Bandyopadhyay T. Beyond job security and money: driving factors of motivation for government doctors in India. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12:12. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dieleman M, Cuong PV, Anh LV, Martineau T. Identifying factors for job motivation of rural health workers in North Viet Nam. Hum Resour Health. 2003;1(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manongi RN, Marchant TC, Bygbjerg IC. Improving motivation among primary health care workers in Tanzania: a health worker perspective. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manafa O, McAuliffe E, Maseko F, Bowie C, MacLachlan M, Normand C. Retention of health workers in Malawi: perspectives of health workers and district management. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:65. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agyepong IA, Anafi P, Asiamah E, Ansah EK, Ashon DA, Narh-Dometey C. Health worker (internal customer) satisfaction and motivation in the public sector in Ghana. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2004;19(4):319–336. doi: 10.1002/hpm.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jabbari H, Pezeshki MZ, Naghavi-Behzad M, Asghari M, Bakhshian F. Relationship between job satisfaction and performance of primary care physicians after the family physician reform of east Azerbaijan province in Northwest Iran. Indian J Public Health. 2014;58(4):256–260. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.146284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prytherch H, Kakoko DC, Leshabari MT, Sauerborn R, Marx M. Maternal and newborn healthcare providers in rural Tanzania: in-depth interviews exploring influences on motivation, performance and job satisfaction. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12:2072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar R, Ahmed J, Shaikh BT, Hafeez R, Hafeez A. Job satisfaction among public health professionals working in public sector: a cross sectional study from Pakistan. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:2. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]