Abstract

Background

Research during the past few decades has greatly advanced our understanding of the cost, quality, and variability of medical care at the end of life. The current health-care policy debate has focused considerable attention on the unsustainable rate of spending and wide regional variation associated with medical treatments in the last year of life. New initiatives aim to standardize quality and reduce over-utilization at the end of life. We argue, however, that focusing exclusively on medical treatment at the end of life is not likely to lead to effective health-care policy reform or reduce costs. Specifically, end-of-life policy initiatives face the challenges of political feasibility, inaccurate prognostication, and gaps in the existing literature.

Objectives

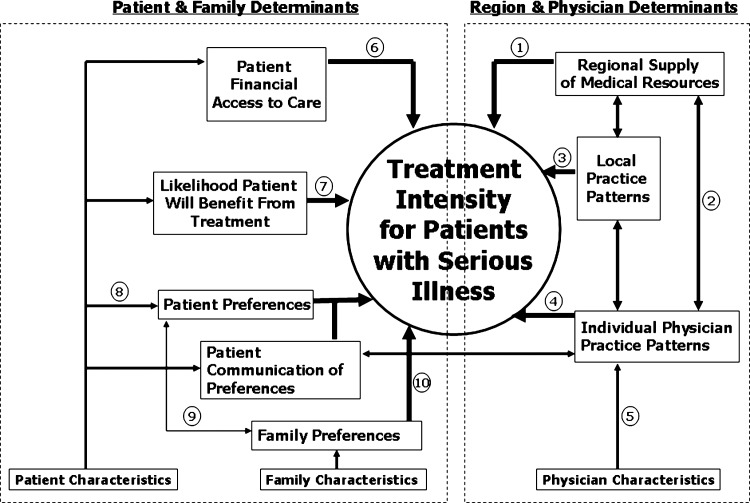

With the ultimate aim of improving the quality and efficiency of care, we propose a research and policy agenda guided by a new conceptual framework of factors associated with treatment intensity for patients with serious and complicated medical illness. This model not only expands the population of interest to include all adults with serious illness, but also provides a blueprint for the thorough investigation of the diverse and interconnected determinants of treatment intensity.

Conclusions

The new conceptual framework presented in this paper can be used to develop future research and policy initiatives designed to improve the quality and efficiency of care for adults with serious illness.

Introduction

The current pace of U.S. health-care spending is unsustainable.1,2 Data suggesting that higher spending in the last year of life may not be associated with greater quality, demonstrable improvements in outcomes, or increased satisfaction3–9 have led to initiatives to standardize quality, decrease treatment variation, and reduce over-utilization and costs at the end of life.

Meaningful health-care reform is unlikely, however, if focused exclusively on end-of-life care. The inability to accurately predict life expectancy for individual patients with serious illness, the innate human struggle to avoid death, and modern political realities pose challenges to policies designed to improve end-of-life care. Instead, reform efforts should focus more broadly on all patients with serious and life-limiting illness. Therefore, we propose a new conceptual framework to guide research and policy aimed at enhancing healthcare efficiency and promoting goal-directed care of patients with serious illness.

A Model for Research and Policy Development

Based on our collective clinical experience and knowledge of theory, as well as the empirical literature in palliative care, health services, and economics, we used a deductive process to develop a theoretical model of factors affecting treatment intensity for seriously ill adults (Fig. 1). During model development, we conducted a narrative review of existing literature supporting or refuting each hypothesized relationship. We discussed available evidence and noted areas where data were insufficient and revised the model using this iterative process. Here we present each theoretical construct, summarize the existing scientific evidence, and in Table 1, highlight areas requiring further investigation. This model provides a framework for more inclusive and comprehensive studies by describing the simultaneous interactions and effects of region, physician, patient, and family determinants on treatment intensity.

FIG. 1.

Model of factors affecting treatment intensity for patients with serious illness.

Table 1.

Selected Suggestions for Future Research

| Conceptual domain | Relationship needing further investigationa | Examples of research questions |

|---|---|---|

| Regional supply of medical resources | 1. The relationship between regional supply and treatment intensity while controlling for local practice patterns, reimbursement structures, and detailed patient characteristics. | Is the association between regional density of hospital beds and likelihood of death in the hospital the same within a fee-for-service system and a capitated managed care system, when controlling for other factors? |

| 2. The association between regional supply of resources and individual physician practice patterns. | Does increased availability of intensive care resources influence physicians' decision to provide high-intensity treatment, when controlling for other factors? | |

| Local practice patterns | 3. The proportion of regional variation in intensity of care due to local practice patterns and the factors that shape these patterns (e.g., local medical “culture,” reimbursement structures). | Is an individual patient's treatment intensity associated with local regional practice patterns including the frequency of hospice referrals, when controlling for other factors? |

| Individual physician practice patterns | 4. The association between individual physician practice patterns and treatment intensity, and how this relationship is modified by regional characteristics. | Do physicians who trained in areas with limited medical resources have practice patterns that are associated with lower treatment intensity, when controlling for other factors? |

| 5. The relationships among personal physician characteristics and individual practice patterns. | When controlling for other factors, is a physician's exposure to a palliative care curriculum in medical school associated with lower intensity practice patterns when caring for patients with serious illness? | |

| Patient financial access to care | 6. The relationship between financial access to care and treatment intensity. | Is cost-sharing (i.e., co-pay) related to treatment intensity among patient with serious illness, when controlling for other factors? |

| Likelihood patient will benefit from treatment | 7. The impact of the patient's likelihood to benefit, as perceived by the patient, the family, and the physician on treatment intensity; and evidence of the effectiveness and the potential for harm of specific therapies for this patient population. | Do patients with more uncertainty around their likelihood to benefit from treatment receive more intense treatment, when controlling for other factors? |

| Patient preferences | 8. The relationship between patient characteristics and treatment preferences, and how preferences shift over time. | Is change in functional status correlated with change in treatment preferences, when controlling for other factors? |

| 9. The relationship between patient treatment preferences and family characteristics and preferences. | Is the availability of family and social support associated with patients' preferences regarding treatment intensity, when controlling for other factors? | |

| Family preferences | 10. The relationship between family characteristics and treatment preferences; and the how family preferences are associated with treatment intensity. | Is a patient's treatment intensity correlated to his or her family's prior experience with life-sustaining therapies? |

Numbers indicate the area of the model depicted in Fig. 1.

Region and Physician Determinants

Geographic location is highly correlated with treatment intensity.3–5,10 This relationship may be mediated through three distinct but related constructs: regional supply of medical resources, local practice patterns, and individual physician practice patterns. These three constructs may also influence each other through direct or modifying effects. We have depicted these bidirectional relationships in the model with two-headed arrows. Further understanding of these relationships will inform situation-specific interventions and policy and may reveal reform opportunities.

Regional supply of medical resources

Local medical resources (e.g., hospital bed supply, medical specialists per capita) influence treatment intensity. This relationship, referred to as “supply-sensitive care,” is supported by several studies.11–15 For example, patients living in areas with more hospital beds available are more likely to be admitted and die in the hospital.14 Hospice availability, in contrast, may reduce treatment intensity.12,15 Further investigation is needed to understand this relationship while adjusting for local practice patterns, reimbursement structures, and patient characteristics.

Local practice patterns

Local patterns of care affect treatment intensity; this hypothesis is supported by studies demonstrating an empiric association.10,11,16–23 These patterns may be related to institutional characteristics (e.g., academic affiliation) or availability of specific professional services (e.g., palliative care programs).15,21,24 Local practice patterns can also exist within organizational systems of health care. For example, Medicare Managed Care patients use hospice more frequently than fee-for-service beneficiaries,25 perhaps due to group practice norms. Further investigation is needed to determine what proportion of observed differences related to local practice patterns is due to local medical “culture” versus reimbursement structures.

Individual physician practice patterns

Individual physicians, even those practicing within the same hospital, may have different practice patterns that influence treatment intensity. These differences may stem from physicians' “intrinsic” characteristics (e.g., race/ethnicity, age, sex, and religion) or “extrinsic” characteristics (e.g., professional specialty, training, years in practice, clinical or personal experiences).26–32 Further research is needed to determine the influence of these characteristics on individual practice patterns.

Patient and Family Determinants

Treatment intensity for patients with serious illness is also affected by patient- and family-related constructs: financial access to care, likelihood of treatment benefit, and patient/family preferences.11,33–38 These theoretical constructs are in turn influenced by specific personal characteristics, including demographic, socioeconomic, medical, functional, and psychosocial factors. The patient- and family-based constructs discussed below provide a theoretical framework for interpreting previously described empiric relationships between patient characteristics and treatment intensity.37–44

Patient financial access to care

We hypothesize that financial characteristics affect treatment intensity. Patients' insurance, benefit design, and ability to pay out-of-pocket for cost-sharing or additional services (i.e., home safety equipment, hired caregivers) influence the care they can access.45 Healthcare consumption decreases with increased patient cost-sharing,46 which has important implications for treatment intensity among the seriously ill. Fee-for-service—the predominant reimbursement model—covers most high-intensity services, including doctor visits, hospitalizations, procedures, and surgeries. In contrast, many other services (e.g., home health aide) that might be needed for the delivery of care in accordance with a patient's preference are not commonly covered. We hypothesize that financial constraints may induce a patient to pursue more intensive hospital-based treatments, which are covered, instead of less intensive home-based treatments, which require higher out-of-pocket expense.

Likelihood patient will benefit from treatment

The likelihood that a patient will benefit from life-prolonging treatments also influences treatment intensity. In general, physicians are unable to accurately predict mortality47–49; therefore, they are challenged to prospectively distinguish appropriate, high-intensity treatment efforts from inappropriate, overly aggressive treatments.49,50 Furthermore, adults with complicated serious illness, are underrepresented in clinical trials,51–53 making it difficult for clinicians to accurately counsel patients about their likelihood of benefiting from a particular therapy. This uncertainty may also contribute to lower rates of hospice use among patients with conditions for which life expectancy is particularly difficult to estimate, such as dementia or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.12,54,55

Consideration of treatment benefit is particularly important for patients with complex medical illness. Specialists caring for such patients may inaccurately estimate patients' potential to benefit from intensive treatment because they may not consider the patient's other comorbidities or have failed to coordinate the patients' care with other physicians. Poorly coordinated care, particularly during transitions across sites of care, is thought to be an important driver of high utilization among adults with serious and complex illness.56–58 Other patient characteristics, such as functional status and quality of life, may also influence the assessment of a patient's likelihood to benefit from a given treatment.

Patient preference

Individual patients may prefer treatment focused on extending life, ensuring comfort, or some combination of these goals. Patient characteristics, such as health status and religiosity, have been shown to influence treatment preferences.59–63 Other patient characteristics may influence preferences, including age, sex, education, marital status, social/family support, functional status, quality of life, personal health-care experience, and experience with the death of a loved one. Finally, race/ethnicity have significant relationships with treatment intensity and some evidence suggests this may be mediated by patient preferences or communication of preferences.64–69

Near the end of life, many seriously ill patients are not able to participate in medical decision-making. For such patients, treatment preferences may be conveyed by formal advance directives or advance care planning discussions. The likelihood of these documents or discussions having been completed is influenced by factors such as income, net worth, and location of residence. For example, a living will may be completed as part of estate planning and nursing homes are required to query newly admitted residents about advance directives.

Prior efforts to systematically elicit and communicate patient preferences for treatment intensity have proved insufficient to change care patterns.70–75 Current understanding of the barriers preventing patient preferences from guiding care is incomplete, and this relationship has not been studied while simultaneously adjusting for the region-related determinants of treatment intensity.

Family preferences

Family members frequently act as surrogate decision makers for patients with serious illness; so family preferences may directly impact treatment intensity. The relationship of the primary decision maker to the patient may affect treatment intensity. The family's treatment preferences may also be influenced by culture or filial responsibilities,69,76,77 as well as their own assessment of the patient's quality of life or likelihood to benefit from treatment. Lastly, just as the patients' characteristics may affect their preferences, the surrogates' characteristics and experiences may also influence preferences.

Interactions

Significant interactions between these constructs may exist. For ease of readership, we do not attempt to depict all possible interactions in Fig. 1 but do highlight here the most notable. First, physicians' practice patterns are likely to affect whether patients have communicated preferences for treatment intensity and the extent to which those preferences guide treatment decisions.78–80 Patient characteristics (e.g., age, sex, race, socioeconomic status) may interact with or influence physician practice patterns.81,82 Evidence also indicates possible interactions between patient race and hospital and regional treatment variations.15,30,83,84

Conclusion

Prior research has greatly advanced our understanding of the cost, quality and regional variation in end-of-life care. Yet the current evidence is insufficient to shape effective reform. We have developed a new conceptual framework for determinants of treatment intensity for seriously ill patients as a blueprint for future research and policy. Increased understanding of the relationships among the described factors and their relative impact on treatment intensity will advance efforts to improve healthcare quality and efficiency for adults with serious illness.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TRSUM/index.html. [May 12;2009 ]. http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TRSUM/index.html

- 2.Fisher ES. Bynum JP. Skinner JS. Slowing the growth of health care costs-lessons from regional variation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:849–852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0809794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.http://www.dartmouthatlas.org. [Jul 20;2009 ]. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org

- 4.Fisher ES. Wennberg DE. Stukel TA. Gottlieb DJ. Lucas FL. Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:273–287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher ES. Wennberg DE. Stukel TA. Gottlieb DJ. Lucas FL. Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:288–298. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skinner J. Chandra A. Goodman D. Fisher ES. The elusive connection between health care spending and quality. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w119–23. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.w119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wennberg JE. Bronner K. Skinner JS. Fisher ES. Goodman DC. Inpatient care intensity and patients' ratings of their hospital experiences. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:103–112. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasaitis L. Fisher ES. Skinner JS. Chandra A. Hospital quality and intensity of spending: Is there an association? Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w566–572. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baicker K. Chandra A. Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries' quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004:W184–197. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.184. Suppl Web Exclusives. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wennberg JE. Fisher ES. Stukel TA. Skinner JS. Sharp SM. Bronner KK. Use of hospitals, physician visits, and hospice care during last six months of life among cohorts loyal to highly respected hospitals in the United States. BMJ. 2004;328:607. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7440.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pritchard RS. Fisher ES. Teno JM, et al. Influence of patient preferences and local health system characteristics on the place of death. SUPPORT investigators. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1242–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb04540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Virnig BA. Kind S. McBean M. Fisher E. Geographic variation in hospice use prior to death. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1117–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher ES. Wennberg JE. Health care quality, geographic variations, and the challenge of supply-sensitive care. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46:69–79. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2003.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher ES. Wennberg JE. Stukel TA, et al. Associations among hospital capacity, utilization, and mortality of US Medicare beneficiaries, controlling for sociodemographic factors. Health Serv Res. 2000;34:1351–1362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Earle CC. Neville BA. Landrum MB. Ayanian JZ. Block SD. Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:315–321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Back AL. Li YF. Sales AE. Impact of palliative care case management on resource use by patients dying of cancer at a Veterans Affairs medical center. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:26–35. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Axelsson B. Christensen SB. Evaluation of a hospital-based palliative support service with particular regard to financial outcome measures. Palliat Med. 1998;12:41–49. doi: 10.1191/026921698671336362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raftery JP. Addington-Hall JM. MacDonald LD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the cost-effectiveness of a district coordinating service for terminally ill cancer patients. Palliat Med. 1996;10:151–161. doi: 10.1177/026921639601000210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez KL. Barnato AE. Arnold RM. Perceptions and utilization of palliative care services in acute care hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:99–110. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelley AS. Gold HT. Roach KW. Fins JJ. Differential medical and surgical house staff involvement in end-of-life decisions: a retrospective chart review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnato AE. Bost JE. Farrell MH, et al. Relationship between staff perceptions of hospital norms and hospital-level end-of-life treatment intensity. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:1093–1100. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emanuel EJ. Ash A. Yu W, et al. Managed care, hospice use, site of death, and medical expenditures in the last year of life. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1722–1728. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sirovich B. Gallagher PM. Wennberg DE. Fisher ES. Discretionary decision making by primary care physicians and the cost of US health care. Health Aff. 2008;27:813. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruera E. Russell N. Sweeney C. Fisch M. Palmer JL. Place of death and its predictors for local patients registered at a comprehensive cancer center. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2127–2133. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Virnig BA. Fisher ES. McBean AM. Kind S. Hospice use in Medicare managed care and fee-for-service systems. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7:777–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garland A. Shaman Z. Baron J. Connors AF. Physician-attributable differences in intensive care unit costs: A single-center study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1206–1210. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200511-1810OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larochelle MR. Rodriguez KL. Arnold RM. Barnato AE. Hospital staff attributions of the causes of physician variation in end-of-life treatment intensity. Palliat Med. 2009;23:460–470. doi: 10.1177/0269216309103664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christakis NA. Asch DA. Physician characteristics associated with decisions to withdraw life support. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:367–372. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wenger NS. Carmel S. Physicians' religiosity and end-of-life care attitudes and behaviors. Mt Sinai J Med. 2004;71:335–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carter CL. Zapka JG. O'Neill S, et al. Physician perspectives on end-of-life care: Factors of race, specialty, and geography. Palliat Support Care. 2006;4:257–271. doi: 10.1017/s1478951506060330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelley AS. Reid MC. Miller DH. Fins JJ. Lachs MS. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator deactivation at the end of life: a physician survey. Am Heart J. 2009;157:702–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.12.011. .e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mebane EW. Oman RF. Kroonen LT. Goldstein MK. The influence of physician race, age, and gender on physician attitudes toward advance care directives and preferences for end-of-life decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:579–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb02573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grande GE. Addington-Hall JM. Todd CJ. Place of death and access to home care services: are certain patient groups at a disadvantage? Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:565–579. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barnato AE. Herndon MB. Anthony DL, et al. Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences? A study of the US Medicare population. Med Care. 2007;45:386–393. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000255248.79308.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wenger NS. Phillips RS. Teno JM, et al. Physician understanding of patient resuscitation preferences: insights and clinical implications. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 Suppl):S44–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emanuel EJ. Young-Xu Y. Levinsky NG. Gazelle G. Saynina O. Ash AS. Chemotherapy use among Medicare beneficiaries at the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:639–643. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shugarman LR. Bird CE. Schuster CR. Lynn J. Age and gender differences in Medicare expenditures at the end of life for colorectal cancer decedents. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16:214–227. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamel MB. Lynn J. Teno JM, et al. Age-related differences in care preferences, treatment decisions, and clinical outcomes of seriously ill hospitalized adults: Lessons from SUPPORT. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 Suppl):S176–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bird CE. Shugarman LR. Lynn J. Age and gender differences in health care utilization and spending for Medicare beneficiaries in their last years of life. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:705–712. doi: 10.1089/109662102320880525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levinsky NG. Yu W. Ash A, et al. Influence of age on Medicare expenditures and medical care in the last year of life. JAMA. 2001;286:1349–1355. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Welch LC. Teno JM. Mor V. End-of-life care in black and white: Race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1145–1153. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanchate A. Kronman AC. Young-Xu Y. Ash AS. Emanuel E. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life costs: why do minorities cost more than whites? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:493–501. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barnato AE. Chang CC. Saynina O. Garber AM. Influence of race on inpatient treatment intensity at the end of life. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:338–345. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0088-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bynum JP. Rabins PV. Weller W. Niefeld M. Anderson GF. Wu AW. The relationship between a dementia diagnosis, chronic illness, Medicare expenditures, and hospital use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morrison RS. Meier DE. Clinical practice. Palliative care. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2582–2590. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp035232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Newhouse JP. Free for all? Lessons from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knaus WA. Harrell FE., Jr Lynn J, et al. The SUPPORT prognostic model. Objective estimates of survival for seriously ill hospitalized adults. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:191–203. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-3-199502010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lynn J. Harrell F. Cohn F. Wagner D. Connors AF. Prognoses of seriously ill hospitalized patients on the days before death: implications for patient care and public policy. New Horiz. 1997;5:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teno JM. Coppola KM. For every numerator, you need a denominator: a simple statement but key to measuring the quality of care of the “dying”. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17:109–113. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bach PB. Schrag D. Begg CB. Resurrecting treatment histories of dead patients: a study design that should be laid to rest. JAMA. 2004;292:2765–2770. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.22.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hutchins LF. Unger JM. Crowley JJ. Coltman CA. Albain KS. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:2061–2067. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee PY. Alexander KP. Hammill BG. Pasquali SK. Peterson ED. Representation of elderly persons and women in published randomized trials of acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2001;286:708–713. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.6.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heiat A. Gross CP. Krumholz HM. Representation of the elderly, women, and minorities in heart failure clinical trials. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1682–1688. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Virnig BA. Marshall McBean A. Kind S. Dholakia R. Hospice use before death: variability across cancer diagnoses. Med Care. 2002;40:73–78. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Christakis NA. Escarce JJ. Survival of Medicare patients after enrollment in hospice programs. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:172–178. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607183350306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anderson G. Knickman J. Changing the chronic care system to meet people's needs. Health Aff. 2001;20:146–160. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coleman EA. Berenson RA. Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:533–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-7-200410050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jencks SF. Williams MV. Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bambauer KZ. Gillick MR. The effect of underlying health status on patient or surrogate preferences for end-of-life care: a pilot study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2007;24:185–190. doi: 10.1177/1049909106299062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rosenfeld KE. Wenger NS. Kagawa-Singer M. End-of-life decision making. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:620–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.06289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Phelps AC. Maciejewski PK. Nilsson M, et al. Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;301:1140. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.True G. Phipps EJ. Braitman LE. Harralson T. Harris D. Tester W. Treatment preferences and advance care planning at end of life: the role of ethnicity and spiritual coping in cancer patients. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:174–179. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johnson KS. Elbert-Avila KI. Tulsky JA. The influence of spiritual beliefs and practices on the treatment preferences of African Americans: a review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:711. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hopp FP. Duffy SA. Racial variations in end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:658–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barnato AE. Anthony DL. Skinner J. Gallagher PM. Fisher ES. Racial and ethnic differences in preferences for end-of-life treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:695–701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0952-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Blackhall LJ. Frank G. Murphy ST. Michel V. Palmer JM. Azen SP. Ethnicity and attitudes towards life sustaining technology. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1779–1789. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Born W. Greiner KA. Sylvia E. Butler J. Ahluwalia JS. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about end-of-life care among inner-city African Americans and Latinos. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:247–256. doi: 10.1089/109662104773709369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Degenholtz HB. Arnold RA. Meisel A. Lave JR. Persistence of racial disparities in advance care plan documents among nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:378–381. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kwak J. Haley WE. Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist. 2005;45:634–641. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Teno JM. Gruneir A. Schwartz Z. Nanda A. Wetle T. Association between advance directives and quality of end-of-life care: a national study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:189–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hofmann JC. Wenger NS. Davis RB, et al. Patient preferences for communication with physicians about end-of-life decisions. SUPPORT investigators. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:1–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-1-199707010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Phillips RS. Wenger NS. Teno J, et al. Choices of seriously ill patients about cardiopulmonary resuscitation: correlates and outcomes. SUPPORT investigators. Am J Med. 1996;100:128–137. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)89450-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brown BA. The history of advance directives. A literature review. J Gerontol Nurs. 2003;29:4–14. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20030901-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rao JK. Alongi J. Anderson LA. Jenkins L. Stokes GA. Kane M. Development of public health priorities for end-of-life initiatives. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jezewski MA. Meeker MA. Sessanna L. Finnell DS. The effectiveness of interventions to increase advance directive completion rates. J Aging Health. 2007;19:519–536. doi: 10.1177/0898264307300198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bito S. Matsumura S. Singer MK. Meredith LS. Fukuhara S. Wenger NS. Acculturation and end-of-life decision making: comparison of Japanese and Japanese-American focus groups. Bioethics. 2007;21:251–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2007.00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Phipps E. True G. Harris D, et al. Approaching the end of life: attitudes, preferences, and behaviors of African-American and white patients and their family caregivers. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:549–554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Back AL. Young JP. McCown E, et al. Abandonment at the end of life from patient, caregiver, nurse, and physician perspectives: loss of continuity and lack of closure. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:474. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang B. Wright AA. Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:480–488. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pinkowish MD. End-of-life care: communication and a stable patient-physician relationship lead to better decisions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:217–219. doi: 10.3322/caac.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schulman KA. Berlin JA. Harless W, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians' recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:618–626. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Van Ryn M. Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians' perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:813–828. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baicker K. Chandra A. Skinner JS. Wennberg JE. Who you are and where you live: how race and geography affect the treatment of Medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004:VAR33–44. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.33. Suppl Web Exclusives. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Barnato AE. Berhane Z. Weissfeld LA, et al. Racial variation in end-of-life intensive care use: a race or hospital effect? Health Serv Res. 2006;41:2219–2237. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]