Introduction

We present a case of new diagnosis of psoriasis in an adult man, with the unusual presentation of a pustular phenotype, precipitated by a perianal streptococcal infection. To our knowledge, this has not been previously reported in the literature.

Case report

A 68-year-old man who was otherwise well, with no personal or family history of skin disease and not on any regular medications, developed a perianal/groin irritation after a digital prostate examination. His general practitioner diagnosed seborrheic dermatitis with secondary fungal infection and treated him empirically with topical betamethasone valerate cream, clotrimazole cream, and oral cephalexin. A swab demonstrated Streptococcus pyogenes.

The eruption progressed into widespread erythematous symmetric papules and plaques and he was referred to a dermatologist, who made an assessment of contact dermatitis with id reaction (potentially to the KY jelly [Reckitt Benckiser, Slough, UK] or latex gloves used in the examination) and secondary infection in the groin. Oral prednisolone was commenced at 50 mg, tapered to 25 mg, as was topical methylprednisolone aceponate. After this, the eruption became pustular and the patient was admitted under dermatology in a tertiary hospital.

On admission, the patient had a low-grade fever but was otherwise hemodynamically stable and systemically well with an increased C-reactive protein level of 43 mg/L (normal <8.0 mg/L) and mildly increased white blood cell count of 12.8 × 109/L (normal 4–11 × 109/L) with associated neutrophilia at 11.66 × 109/L (normal 1.8-7.5 × 109/L) and lymphopenia at 0.57 × 109/L (normal 1.5-3.5 × 109/L). Calcium and albumin levels were normal. The monomorphic pustules on an erythematous base were initially confined to the groin and perianal region (Fig 1), but rapidly progressed to the legs and torso. Repeated perianal swabs demonstrated S pyogenes. Biopsy specimen of an abdominal plaque demonstrated multiple discrete mounds of parakeratosis with degenerate neutrophilia, loss of the granular layer, developing psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, and a subclinical macropustule (Fig 2). There were no eosinophils in the dermal infiltrate and no apoptosis. Periodic acid–Schiff–diastase and Gram stains were negative. These histologic features supported acute pustular psoriasis rather than a drug eruption, such as acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.1

Fig 1.

Well-demarcated salmon-pink to erythematous plaque with overlying scale and pustules on the right side of the groin.

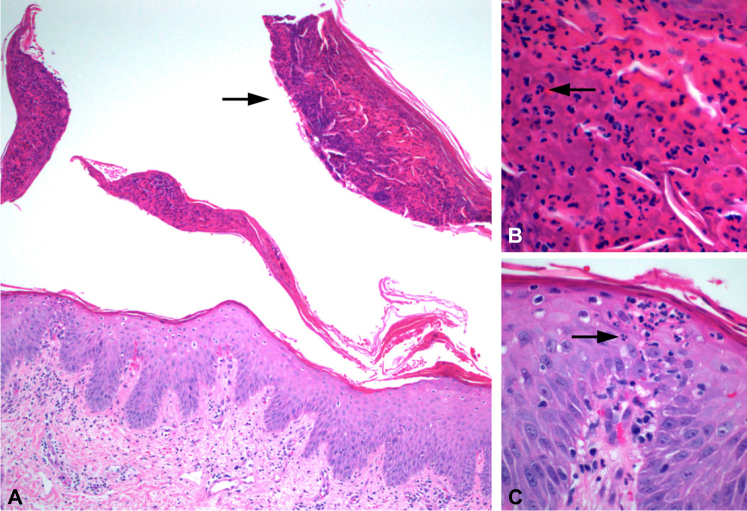

Fig 2.

A, Pustular psoriasis: largely detached macropustule (arrow) and developing psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia. B, Close-up view of macropustule with numerous neutrophils (arrow). C, Neutrophil spongiosis (arrow).

Cephalexin (day 3) and oral prednisolone were ceased on admission. The patient was treated with clindamycin (14 days), topical steroids, potassium permanganate soaks, clioquinol 0.5%/betamethasone valerate (to groin), and 20 mg acitretin. His eruption resolved over several weeks. Subsequent patch testing to the Australian Standard Series, KY jelly, and latex 1 month after cessation of prednisolone demonstrated no positive reactions. Acitretin was ceased after 4 months and at 9 months the patient reported no ongoing sequelae.

Discussion

Pustular psoriasis is an uncommon initial presentation of psoriasis in adults. Contact dermatitis has been implicated as a precipitant of pustular psoriasis in 2 case reports.2, 3 Negative patch test results after the patient had been off prednisolone confirmed that contact dermatitis was not the cause of this patient's eruption.

S pyogenes has a well-established association with both acute and chronic psoriasis, particularly guttate psoriasis. The prevailing current theory regarding this relationship is that psoriasis is an autoimmune disease triggered by the bacterial microbiota of the skin, including the presence of Streptococcus.4 It has been suggested that the streptococcal antigen sensitizes T cells to epitopes in skin keratin.5 Perianal6 and vulvar7 streptococcal infection has been linked to the development of psoriasis in children.

Antibiotic treatment for Streptococcus has not been shown to be reliably effective in the treatment of established guttate or chronic plaque psoriasis8 but may be beneficial in early infection in children with psoriasis.9 Withdrawal of topical and systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine has been shown to trigger pustular psoriasis in some cases,10 and avoidance of potentially irritating topical preparations such as tar and dithranol when pustules are present is generally accepted.

This case demonstrates pustular psoriasis as the initial presentation of psoriasis in an adult after perianal S pyogenes infection. A search of PubMed and MEDLINE did not reveal any reports of pustular psoriasis as the initial presentation of psoriasis in an adult secondary to a cutaneous infection. This case highlights the need for the clinician to consider a nonpharyngeal streptococcal infection as a cause of a pustular psoriasiform eruption.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kardaun S.H., Kuiper H., Fidler V. The histopathological spectrum of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) and its differentiation from generalized pustular psoriasis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1220–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2010.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jo J., Jang H.S., Ko H.C. Pustular psoriasis and the Koebner phenomenon caused by allergic contact dermatitis from zinc pyrithione-containing shampoo. Contact Derm. 2005;52(3):142–144. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielson N.H., Menne T. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by zinc pyrithione associated pustular psoriasis. Am J Contact Dermatitis. 1997;8(3):170–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fry L., Baker B.S., Powels A.V. Psoriasis is not an autoimmune disease? Exp Dermatol. 2015;24:241–244. doi: 10.1111/exd.12572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu W., Debbaneh M., Moslehi H. Tonsillectomy as a treatment for psoriasis: a review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25(6):482–486. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2013.848258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patrizi A., Costa A.M., Fiorillo L. Perianal streptococcal dermatitis associated with guttate psoriasis and/or balanoposthitis: a study of five cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11(2):168–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1994.tb00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer G., Rogers M. Vulvar disease in children: a clinical audit of 130 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17(1):1–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dogan B., Karabudak O., Harmanyeri Y. Antistreptococcal treatment of guttate psoriasis: a controlled study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:950–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim S.K., Kanf H.Y., Kim Y.C. Clinical comparison of psoriasis in Korean adults and children: correlation with serum anti-streptolysin O titers. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:295–299. doi: 10.1007/s00403-009-1025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson A., Van Voorhees A.S., Hsu S. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]