Abstract

The observation of ionic signaling dynamics in intact pancreatic islets has contributed greatly to our understanding of both α- and β-cell function. Insulin secretion from β-cells depends on the firing of action potentials and consequent rises of intracellular calcium activity ([Ca2+]i). Zinc (Zn2+) is cosecreted with insulin, and has been postulated to play a role in cell-to-cell cross talk within an islet, in particular inhibiting glucagon secretion from α-cells. Thus, measuring [Ca2+]i and Zn2+ dynamics from both α- and β-cells will elucidate mechanisms underlying islet hormone secretion. [Ca2+]i and intracellular Zn2+ can be measured using fluorescent biosensors, but the most efficient sensors have overlapping spectra that complicate their discrimination. Hyperspectral imaging can be used to distinguish signals from multiple fluorophores, but available hyperspectral implementations are either too slow to measure the dynamics of ionic signals or not suitable for thick samples. We have developed a five-dimensional (x,y,z,t,λ) imaging system that leverages a snapshot hyperspectral imaging method, image mapping spectrometry, and light-sheet microscopy. This system provides subsecond temporal resolution from deep within multicellular structures. Using a single excitation wavelength (488 nm) we acquired images from triply labeled samples with two biosensors and a genetically expressing fluorescent protein (spectrally overlapping with one of the biosensors) with high temporal resolution. Measurements of [Ca2+]i and Zn2+ within both α- and β-cells as a function of glucose concentration show heterogeneous uptake of Zn2+ into α-cells that correlates to the known heterogeneities in [Ca2+]i. These differences in intracellular Zn2+ among α-cells may contribute to the inhibition in glucagon secretion observed at elevated glucose levels.

Introduction

Diabetes is characterized by chronic hyperglycemia resulting from insufficient insulin due to either dysfunction or destruction of β-cells in the islet of Langerhans. Islets are endocrine microorgans that affect glucose homeostasis by regulated secretion of hormones, including insulin as well as its counterregulatory hormone, glucagon, which is secreted from α-cells (1, 2). Specific interactions between cells in the islet result in dynamic responses to glucose (3, 4) that are not seen from dispersed cells (5). Thus, information about cell-cell interaction mechanisms within the islet is crucial toward a more complete understanding of diabetes.

The role of Zn2+ in insulin biosynthesis and secretion has been well described in the past (6), and more recently the importance of Zn2+ (and Zn2+ transporters) within pancreatic islets has been correlated to improved peripheral insulin sensitivity (7). Furthermore, polymorphisms in the Zn2+ transporter, ZnT8, were discovered to lead to increased risk for type 2 diabetes, making it one of the so-called diabetes genes (8). Zn2+ in the pancreas is concentrated mainly in the islets (9). In the β-cell, Zn2+ is cosecreted with insulin during exocytosis, and this secreted Zn2+ has been proposed to act as a paracrine factor on neighboring α-cells (10) or perhaps to be transported back into the β-cells (11). High concentrations of Zn2+ in islets can also be toxic because of its role in oxidative stress, which can lead to apoptosis (12). To better understand the role of intracellular Zn2+ in both α- and β-cells, we can measure the activity of this ion and correlate it with the primary function of these cells: secretion of glucagon and insulin. Insulin secretion requires firing of action potentials that increase [Ca2+]i, so under normal conditions this activity can be used as a surrogate for insulin secretion. Thus, we assayed [Ca2+]i and Zn2+ levels simultaneously in both cell types as a function of glucose concentration to better understand the mechanisms and the processes that are involved in hormone secretion.

Fluorescence microscopy has long been a useful tool for islet studies (13), and has been combined with complementary approaches to maximize the quantitative spatial, functional, and morphological information from the experiments (14, 15). However, the molecular signaling processes underlying hormone secretion are fast, and three-dimensionally resolved fluorescence imaging techniques like confocal microscopy often cannot provide sufficient temporal resolution to follow such dynamics. This limitation is exacerbated by the need to follow multiple pathways and secreted hormones simultaneously. Typically, quantitative imaging of multiple fluorescent labels requires sequential exposures with multiple laser lines and detectors, thus increasing the image acquisition time and increasing the total dose of illumination intensity. One approach to imaging multiple probes is hyperspectral imaging, where the emission spectrum is collected for each pixel in an image. This approach can be used to discriminate spectrally overlapping fluorophores (16) but most hyperspectral implementations require sequential spatial (17) or spectral (18) acquisitions to obtain the x, y, λ datacube. Such sequential approaches slow the overall data acquisition time and increase photobleaching probability, and may require additional optical elements that reduce the light throughput levels (19).

A recently developed approach, image mapping spectrometry (IMS), can overcome these limitations by providing a (x, y, λ) datacube with a single snapshot (20). This method relies on an image mapper consisting of multiple mirror facets that reorganize the image so that blank regions are created within the intermediate image. An array of dispersing prisms is then used to spread the spectrum from each pixel into the void regions. The spatial and spectral information in each voxel (x, y, λ) of the original image is maintained in this process, establishing a one-to-one correspondence with the pixels on the camera chip. We have previously used the IMS approach to image the interplay of Ca2+ and cAMP signaling in β-cells (21). However, those experiments were limited to single cells because the IMS was coupled to a widefield microscope, which does not provide the optical sectioning required for intact islet imaging. To extend the IMS approach to three-dimensionally resolved imaging, it is possible to use spinning disk confocal microscopy (16), structured illumination (22), or selective plane illumination microscopy (SPIM) also known as light-sheet microscopy.

SPIM can surpass some fundamental limitations of single objective lens-based methods, and provide optical sectioning with the acquisition speed of a widefield microscope. In SPIM, the sample is illuminated by a thin sheet of light, created using a cylindrical lens (23) or rapidly scanning a Gaussian beam (24). The resulting excitation of fluorescence is confined to that thin sheet, and the fluorescence is collected orthogonally to the illumination by a second objective lens. The SPIM approach provides optical sectioning for imaging of thick samples while also reducing photobleaching (25). Recently, light-sheet microscopy has been successfully applied to multicolor imaging, either by means of multiphoton excitation (26), or with a line scanning hyperspectral detection (27). However, both approaches show fundamental limitations. In the first case, the spectral overlap of the most common fluorophores used in biology constrains the observation of multiple markers to just a few at the same time. In the second case, the limited time resolution of the spectral scanning approach used significantly restricts the capability to observe fast dynamics in living samples.

We describe the combination of IMS with inverted selective plane illumination microscope (iSPIM) (28). With this system, we demonstrate the simultaneous acquisition of multiple overlapping fluorophores, labeling different hormones, second messengers, and paracrine factors within intact mouse pancreatic islets, with a single excitation wavelength. The iSPIM provides high spatial and temporal resolution (each image acquired with a 250 ms exposure time with ∼520 nm x,y resolution), whereas the IMS provides spectral resolution of a few nanometers. The combination of these two techniques opens a new, to our knowledge, path to the investigation of complex three-dimensional (3D) systems with multiple biosensors.

Materials and Methods

All animal studies were conducted in compliance with the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Islet isolation was performed according to the protocol described in (29). To identify α-cells within intact islets, we used a transgenic mouse model, which contains a cross of ROSA26-floxed-tandem red fluorescent protein (tdRFP) (30) and a glucagon-promoter driven Cre (31). This crossed line results in islets that contain tdRFP expressing α-cells, which allows measurement of Ca2+ and Zn2+-related dynamics specifically in these cells.

Intracellular Ca2+ and Zn2+ ion activity was assayed in islet cells using the cell permeant indicator dyes, Calcium Orange-AM (ex. 549 nm/em. 576 nm, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and Fluozin-AM (ex. 494 nm/em. 516 nm, Life Technologies, Thermo Scientific). Islets were labeled with both indicator dyes as previously described (32, 33). Briefly, 1 mM dye in dimethyl sulfoxide was diluted in 1 ml Krebs Ringer Bicarbonate HEPES buffer (KRBH) to a final concentration of 4 μM. To disperse the hydrophobic dye molecules into solution, the final buffer were sonicated for 10 min. Islets were incubated in this buffer at room temperature for 45 min with gentle rocking. This results in homogeneous labeling among cells in the outer few layers of the islet.

Imaging experiments were performed on live islets mounted on poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips. Unlike many light-sheet imaging approaches, the iSPIM does not require complex sample preparation (i.e., agar embedding), but instead accommodates any specimen mounted on a standard coverslip. An objective heater was used to maintain the sample chamber at 37°C. Three glucose concentrations in KRBH were used for the imaging experiments: 1, 2, and 10 mM glucose. ZnCl2 (Acros Organics, Thermo Scientific) was diluted in KRBH, to a final concentration of 30 μM. The pH of all solutions used was stabilized at 7.4.

Standard image processing was performed on the images after the linear unmixing. Considering a blank region in the image as a reference for the background, the mean background value for each time point was subtracted in the final image. Calcium Orange and Fluozin display a change in their fluorescence intensity when calcium or zinc binding occurs, but they do not permit ratiometric measurements. Variation in fluorescence intensity can reflect a change in dye concentration or a change in ion concentration. Each trace was normalized to the initial value of fluorescence and unstimulated control experiments were performed to account for any changes due to photobleaching or increases in dye concentration over the experimental time course. The experimental data were averaged over at least 15 cells to account for differences that might result from the different indicator concentrations in each cell. For visualization purposes, the signals were normalized to their own maximum intensity.

Results

Instrument design and construction

The operating principle of the IMS system used is shown in Fig. 1 following the principles as previously detailed (19, 20, 21, 34), and calibrated as described in (35). Laser illumination used a diode 50 mW 488 nm laser (Picarro, Santa Clara, CA), coupled to the imaging system by a Toptica FiberDock Universal Fiber Coupler (Toptica Photonics AG, Graefelfing, Germany). The power measured coming out of the illumination objective was 0.9 mW. For the implementation of hyperspectral imaging in a light-sheet excitation environment, we mapped the fluorescent image coming from a commercial iSPIM (Applied Scientific Instrumentation: ASI, Eugene, OR) mounted on a Nikon TE 300 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) (Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material) to the field stop of the IMS system. The iSPIM is equipped with two Nikon CFI APO 40XW NIR objectives (0.8 NA) for both illumination and detection paths. The intermediate image coming from the microscope (Fig. 1 a) is relayed by a 2.5× optical relay system (using a 2.5× Zeiss EC Plan Neofluar Objective, NA 0.075 and a 164.5 mm Zeiss Tube lens, Fig. 1 b) (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Thornwood, NY) onto the image mapper (Fig. 1 c), which is a custom fabricated multifaceted aluminum mirror.

Figure 1.

The working principle of the IMS. The intermediate image from the microscope (a) is relayed by a low magnification system (b) to fit the size of the image mapper. The image mapper (c) is composed by multiple facets (here represented for simplicity as a 12 facets mirror) redirects the image zones into different areas creating blank regions in between. A low NA collecting objective (d) directs the mapped image to a Prism/Lens array (e). An array of prisms disperses each pixel depending on the wavelength, and a lens array refocuses the light onto the sCMOS detector (f). The array forms a 5 × 6 set of subimages, each representing a spectrally dispersed mapping of the original image (figure adapted from (35)). To see this figure in color, go online.

The image mapper redirects the image zones into different pupils. The number of multiple mirror facets (M), the length of the mirror facets in relation to the image point spread function (N), and the number of tilt angles (L) together determine the size N × M × L of the 3D (x, y, λ) datacube. N is the total number of spatial data points in the x-dimension, M is the total number of spatial data points in the y-dimension, and L is the total number of spectral data points (λ). The mapper consists of 210 microscale (width = 75 μm) mirror facets. Each mirror facet has a two-dimensional tilt angle, which maps a single line of pixels of the intermediate image onto a unique place in the final image. This mapping leaves blank regions in the final image, where prisms disperse each pixel of the image as a function of the fluorescence wavelength. The reflected light from the mapper is collected by a MVXPLAPO 0.63X (0.15 NA) Olympus objective (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) (Fig. 1 d), directed into 30 corresponding pupils. The prism-lenslet array (Fig. 1 e) contains a custom-designed array of 5 long prisms (H-ZF62, 20°) and 30 achromatic doublets (d = 2 mm, f = 12 mm), which form the reimaging optics unit as in (19) and are positioned directly in front of the detector (sCMOS camera PCO Edge 5.5, Fig. 1 f) (PCO AG, Kelheim, Germany), which acquires a set of subimages representing the dispersed mapping of the image (Fig. 1 g).

To maintain the system’s telecentricity and maximize sampling, the prism-lenslet array must not be larger than the sensor itself, so it needs to be located in close proximity to the sensor due to short focal lengths. To limit the cross talk and to prevent leakage of light between adjacent pupils, a mask is placed before the reimaging lenses. The final datacube has dimensions 322 × 210 × 60 (x, y, λ). The field of view and the spatial resolution depend on the microscope objective, and for the results presented it is 109 × 71 and 0.52 μm. The fluorescence spectrum is measured from 480 to 660 nm spread over 60 spectral channels with an average interval of 3 nm. The capability of the system to resolve overlapping spectra depends of the spectral sampling. Following Nyquist, at least twice the spectral sampling is needed to discriminate between overlapping spectra, so in our case, the peaks of overlapping spectra would need to differ by at least 6 nm. However, linear unmixing (36) is a pixel-based method that is susceptible to errors due to measurement noise, and these errors affect the unmixing. This can especially be a problem for low light levels, as seen in live cell imaging, where light exposure has to be minimized to prevent photoxicity. sCMOS sensors provide very low readout noise (<3 e−1), but it is still important to evaluate the achievable signal/noise ratio (SNR) for the three fluorophores as a function of wavelength, as shown in Fig. S2. SNR was calculated as the ratio between the mean value of the intensity of the signal in a region of interest (a single cell) and the standard deviation of the background in the same image (calculated with the statistical analysis of 10 different blank region in the image), for each channel in the (x, y, λ) datacube. SNR is lower for the tdRFP signal because its excitation efficiency with 488 nm light is lower than Fluozin or Calcium Orange. The SNR is still sufficient to prevent errors in the linear unmixing process (Fig. S2).

We used a mapper design based on a 5 × 6 pupil array, which comes close to matching the aspect ratio of the sCMOS sensor format (2560 × 2160; pixel size = 6.5 μm). However, the length of the single facet is longer than the width of all facets, so spatial sampling is lower in the direction perpendicular to facet. This mismatch affects the spatial resolution of the image, yielding an effective resolution of ∼520 nm, compared to the previously published iSPIM resolution of 330 nm (37). Regardless of this small distortion, there is still a one-to-one correspondence between each voxel in the datacube (x, y, λ) and each pixel on the sCMOS camera. This leads to a trade-off between the maximal spectral resolution and spatial dimension of the field of view, because the total number of voxels cannot exceed the total number of pixels of the camera chip. Depending on the application, it is possible to increase or decrease the spectral sampling, reducing or enlarging the spatial sampling, and hence the field of view. For this first instrument, we chose a datacube format 322 × 210 × 60 produce a number of datacubes that fit with the currently available 5.5 Mpixel sCMOS sensors. In the future, larger frame sCMOS cameras will likely become available, and the optical design described previously could be adapted to those.

Stability measurements (Fig. S3) showed that islet motion during 10 repetitions of adding and removing the aqueous medium with a pipette was <1 pixel. This movement is significantly less than the spatial resolution, and thus does not affect image quality.

Data acquisition and analysis

The combination of IMS and iSPIM provides quantitative information from multiple biosensors within whole islets under physiological conditions. We used islets with α-cells expressing a glucagon-Cre driven tdRFP, combined with loading of Calcium Orange-AM and Fluozin-AM to yield triply labeled specimen. The two biosensors and the fluorescent protein were excited simultaneously with a single wavelength (488 nm) in the iSPIM, and the IMS discriminated the resulting fluorescence spectra from each label. Reference spectral signatures were acquired in singly labeled samples (Fig. 2 A), and these emission spectra were used to separate the contribution of each fluorophore in mixed signals coming from triply labeled islets (Fig. 2 B). Knowing the emission spectra of the three fluorophores, a simple linear unmixing procedure (36) was applied to gather the individual channel information. The precise contributions from each spectral channel could be separated even though Calcium Orange and tdRFP have substantially overlapping spectra.

Figure 2.

Relative intensity contribution coming from each fluorophore. Fluorescence spectra from the two biosensors and the fluorescent protein were obtained in control experiments performed with a single fluorophore (A). Selected channels from a (x, y, λ) datacube show the intensities for each channel in an islet containing all three fluorophores (B). The three unmixed fluorescence spectra are shown in black (black solid square Fluozin, black solid triangle down Calcium Orange, black solid star tdRFP). The scale bar represents 20 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

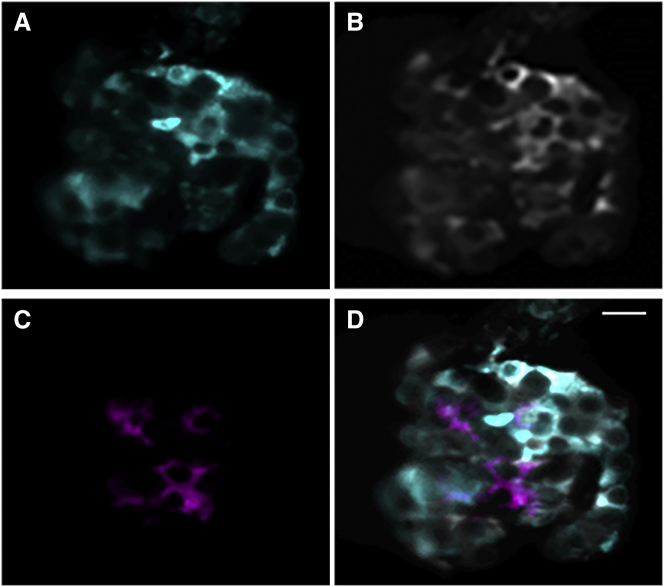

The iSPIM system allowed us to obtain 3D volumes (∼50 images per islet, with a 2 μm step size) of intact islets in ∼12 s total acquisition time, with a single frame exposure time of 250 ms. Each two-dimensional image within the 3D volume represents an (x, y, λ) datacube. A (x, y, λ) datacube is associated with each plane acquired in the z-stack. Linear unmixing for each plane results in a three-color z-stack. A representative maximum projection of the (x, y, z) acquisition of an islet is shown in Fig. S4. The linear unmixing of a central plane within an islet (∼40 μm from the top of the islet) is shown in Fig. 3. The contributions to this plane from each of the three fluorophores are shown in (A) (fluozin), (B) (Calcium Orange), and (C) (tdRFP expressing α-cells). The three unmixed spectra demonstrate the capabilities of the system in acquiring multiple fluorophores signal with a single wavelength from a thick, multicellular sample. The 488 nm excitation efficiency varies for each fluorophore, so the fluorescence images have been normalized to the maximum for each spectrum for visualization purposes.

Figure 3.

IMS-iSPIM fluorescence images of a triply labeled live intact pancreatic islet. Fluorescence signal was unmixed and pseudocolored for the Zn2+ indicator dye fluozin (A), the Ca2+ indicator dye Calcium Orange (B), and the genetically labeled tdRFP α-cells (C). The overlay of the three unmixed signals is shown in (D). The scale bar represents 20 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

Ca2+ and Zn2+ dynamics in α- and β-cells

We evaluated the signals coming from α- and β-cells, for both the Zn2+ and Ca2+ indicators. For the β-cells, we analyzed data from 15 different cells in six different islets. Fig. 4 shows a representative time course of Fluozin and Calcium Orange fluorescence signals averaged over intracellular regions of interest in 15 different β-cells within a single islet as a function of varying glucose levels. In the presence of low glucose, there is minimal [Ca2+]i, as expected. At the same time, the intracellular Zn2+ signal remains constant, because insulin secretion (and concomitantly Zn2+ secretion) is inhibited.

Figure 4.

Quantitative analysis of Ca2+ and Zn2+ indicator dye in β-cells. Data are averaged over regions of interest measurements from 15 different β-cells within a single islet. Data were acquired on a stack of 10 planes to provide a temporal sampling every 3 s. [Ca2+]i oscillations in β-cells at high glucose correspond to a simultaneous decrease in Zn2+ due to insulin (and concomitant Zn2+) secretion. Adding 30 μM ZnCl2 leads to a recovery in Zn2+ levels, suggesting the uptake of Zn2+ from the extracellular space.

Increasing the glucose concentration leads to oscillations in [Ca2+]i, which correspond to pulses of insulin secretion. These oscillations exhibit frequencies comparable to those previously reported (32). At the same time, the fluorescence intensity of the Zn2+ indicator decreases, because insulin and Zn2+ are cosecreted by the β-cells and released into the extracellular space.

Zn2+ has an estimated concentration of ∼20 mM in pancreatic β-cells (38). Because Zn2+ is known to be involved in multiple processes related to β-cell function, we measured the effect of adding ZnCl2 on the reuptake of extracellular Zn2+ into the cell. Addition of 30 μM ZnCl2 stimulated a rapid and significant increase in the intracellular Zn2+ indicator fluorescence, although it still did not return to its initial level before glucose elevation. These β-cell behaviors were as expected given the role of Zn2+ in metabolic signaling in addition to its role in the crystallization of insulin (39).

In contrast to its role in β-cells, the role of Zn2+ in α-cells is not as well understood. To address this point, we measured fluorescence from the Ca2+ and Zn2+ indicator dyes in islet α-cells. Specific signals from the α-cell could be acquired using the optical sectioning capabilities of the iSPIM coupled with spectral identification of tdRFP-labeled α-cells distinguished by the IMS. In these experiments, the glucose concentration was increased from 1 to 2 to 10 mM in ∼5 min intervals. Consistent with previous results from our lab (40), the α-cells form a heterogeneous set of populations, which can be defined by the presence or absence of [Ca2+]i oscillations. Fig. 5, A and B, show the observed time courses of [Ca2+]i and Zn2+ from intracellular regions of interest in two representative α-cells for each population.

Figure 5.

Quantitative analysis of Ca2+ and Zn2+ indicator dyes in α-cells. Time course traces from representative cells from each of two α-cell populations within the islet show an anticorrelation between the fluorescence intensities of Ca2+ and Zn2+ indicators (A and B). An entire z-stack was acquired at each time point (every 13 s). Average values over 15 different α-cells for each population confirms the anticorrelation between the two sets of populations (C and D). Data were normalized (independently for the two populations) to the maximum intensity value at high glucose (10 mM) concentration for both calcium and zinc. Two-way analysis of variance was carried out as a statistical test within each data set. ++, p < 0.01 vs. 1 mM glucose conc. in Calcium_1; ∗∗, p < 0.01 vs. 1 mM glucose concentration in Zinc_2.

At the lower glucose levels, both cells exhibit similar behavior in terms of fluorescence signal coming from the Zn2+ or the Ca2+ indicator, but as glucose levels are increased, the situation starts to change. One set of α-cells (population 1) shows oscillating [Ca2+]i, which is coupled with a relatively constant signal from the Zn2+ indicator dye, whereas the other set of α-cells (population 2) shows another behavior. In population 2, [Ca2+]i is relatively constant over time, although there is a 40% increase in fluorescence intensity of the Zn2+ indicator. For acquisition of a whole islet z-stack time sampling is limited to every 13 s, but this data could be used to detect potential differences between α-cell behaviors, depending on their position in the islet. However, the data showed that the behavior of the two α-cell populations was independent of the cell position within the islet. Adding 30 μM ZnCl2 increased [Ca2+]i oscillation frequency and amplitude (Fig. S5), but the anticorrelation between [Ca2+]i and Zn2+ behaviors is still present. Fig. 4, C and D, show the average values for the two indicator dyes obtained over 15 different α-cells for each population, with at least 10 measurements taken over 3 min for each glucose concentration. This ensemble average shows a significant anticorrelation between Ca2+ and Zn2+ signals, consistent with a role for Zn2+ in the signaling cross talk between α- and β-cells.

Discussion

The combination of iSPIM and IMS yields a novel, to our knowledge, snapshot hyperspectral imaging technique with intrinsic optical sectioning (Fig. 1). We used this instrument to measure the dynamics of Ca2+ and Zn2+ in both α- and β-cells within intact pancreatic islets. The IMS-iSPIM approach allowed us to simultaneously image three different fluorophores with single wavelength excitation, and simultaneously study the dynamics of two important ions in two different cell types within a thick multicellular specimen. The IMS-iSPIM acquires images with high temporal (250 ms) and spatial (520 nm) resolution. Each image of the stack is a (x, y, λ) datacube containing the spatial and spectral information from that specific plane of interest. This was made possible by the intrinsic optical sectioning capability of the light sheet microscope and the extremely high sensitivity of the IMS, and it represents the first, to our knowledge, demonstration of snapshot hyperspectral imaging in a thick multicellular sample (Fig. 2). The snapshot hyperspectral light-sheet combination presented here allows 3D acquisition of 50 planes in 12 s, which is faster than any other hyperspectral system. However, the high temporal resolution of this architecture comes at a cost of a slightly reduced spatial field of view. Because the data needed to form the spectral datacube are distributed on the same detector at the same time, there is an intrinsic trade-off between the amount of spectral and spatial information that can be acquired. This trade-off can be optimized for any given imaging situation, and could be improved with the fabrication of new mappers. In this case presented here, we used a mapper consisting of 60 different spectral channels that span most of the visible spectral range. By reducing the number of spectral channels to focus on a smaller part of the spectrum, the spatial sampling can be improved. A recently published scanning hyperspectral light-sheet combination (27) was designed to maintain a bigger field of view, but the scanning approach does not allow the imaging speed required to follow fast ion dynamics. Such trade-offs are typical in fluorescence microscopy (for example, in super resolution microscopy (41)), and there is no best combination of spatial and spectral resolution for hyperspectral light sheet imaging. Depending on the experimental needs, snapshot hyperspectral light sheet can be successfully applied to achieve high spectral resolution optimizing temporal, spatial, or spectral resolution.

Using linear unmixing, we measured the cellular dynamics of Ca2+ and Zn2+ in both α- and β-cells in the presence of low and high glucose concentrations. As expected, intracellular Zn2+ in β-cells decreased as [Ca2+]i oscillations caused pulses of insulin (along with Zn2+) to be secreted (Fig. 3). Adding Zn2+ to the media partially compensated for this loss in intracellular Zn2+, but Zn2+ still did not return to its initial level before glucose elevation. This is consistent with the known role of intracellular Zn2+ in β-cell processes other than the crystallization of insulin (39). In the α-cells, Zn2+ is proposed to be a paracrine factor that regulates glucagon secretion (11, 29). Our data show a significant anticorrelation between Ca2+ and Zn2+ signals (Fig. 4). The differential behavior of Zn2+ between the different populations of α-cells supports the putative role of this ion in the regulation of glucagon secretion. In the presence of elevated glucose (and associated insulin secretion), the islet glucagon secretion is reduced (29), with one set of α-cells, population 1, exhibits [Ca2+]i oscillations, which would be expected to cause glucagon secretion. At the same time, the second set of α-cells, population 2, show dramatic increases in intracellular Zn2+, and no increase in [Ca2+]i transients. This would support a model where increased intracellular Zn2+ may prevent the development of [Ca2+]i oscillations in population 2, and thus contribute to the glucose inhibition of glucagon secretion (11). A potential mechanism underlying this effect could be that Zn2+ regulates KATP channel function not only from the extracellular side but also from the intracellular side (42). Further studies examining the dynamic levels of Zn2+ and [Ca2+]i in α-cells from islets with genetic mutations to the KATP channels (43) and/or Zn2+ transporters (44) can test this hypothesis.

The data shown here demonstrates the power of this optical-sectioning hyperspectral imaging approach, and shows how the IMS is ideally suited for snapshot hyperspectral imaging with light-sheet illumination. The IMS-iSPIM approach could also be extended to deep tissue imaging by leveraging the recently demonstrated combination of two-photon excitation with light-sheet microscopy (26, 45, 46, 47). Using two-photon excitation would not only permit deeper imaging, but could also open the possibility of using many different fluorophores with a single excitation wavelength.

Author Contributions

D.W.P. and T.T. designed research; Z.L. built the iSPIM system, performed experiments, and analyzed data; J.D. and T.U.N. built and calibrated the IMS system; Z.L. and J.D. built and aligned the iSPIM-IMS combination; A.U. provided biological samples; D.W.P., Z.L., A.U. and T.T. wrote and edited the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Troy Hutchens from Vanderbilt University Medical School and Christopher Reissaus from Washington University in St. Louis for meaningful and helpful discussions.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants DK085064 and DK098659 to D.W.P., NIH grant R21 EB011598 to T.T., a Louise B. McGavock Chair at Vanderbilt University, and the Edward Mallinckrodt Professorship at Washington University.

Editor: Klaus Hahn.

Footnotes

Five figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)30460-X.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Orci L., Unger R.H. Functional subdivision of islets of Langerhans and possible role of D cells. Lancet. 1975;2:1243–1244. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smyth S., Heron A. Diabetes and obesity: the twin epidemics. Nat. Med. 2006;12:75–80. doi: 10.1038/nm0106-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baetens D., Malaisse-Lagae F., Orci L. Endocrine pancreas: three-dimensional reconstruction shows two types of islets of langerhans. Science. 1979;206:1323–1325. doi: 10.1126/science.390711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabrera O., Berman D.M., Caicedo A. The unique cytoarchitecture of human pancreatic islets has implications for islet cell function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2334–2339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510790103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benninger R.K.P., Piston D.W. Cellular communication and heterogeneity in pancreatic islet insulin secretion dynamics. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;25:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emdin S.O., Dodson G.G., Cutfield S.M. Role of zinc in insulin biosynthesis. Some possible zinc-insulin interactions in the pancreatic B-cell. Diabetologia. 1980;19:174–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00275265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang X., Shay N.F. Zinc has an insulin-like effect on glucose transport mediated by phosphoinositol-3-kinase and Akt in 3T3-L1 fibroblasts and adipocytes. J. Nutr. 2001;131:1414–1420. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.5.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicolson T.J., Bellomo E.A., Rutter G.A. Insulin storage and glucose homeostasis in mice null for the granule zinc transporter ZnT8 and studies of the type 2 diabetes-associated variants. Diabetes. 2009;58:2070–2083. doi: 10.2337/db09-0551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zalewski P.D., Millard S.H., Mahadevan I. Video image analysis of labile zinc in viable pancreatic islet cells using a specific fluorescent probe for zinc. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1994;42:877–884. doi: 10.1177/42.7.8014471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egefjord L., Petersen A.B., Rungby J. Zinc, alpha cells and glucagon secretion. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2010;6:52–57. doi: 10.2174/157339910790442655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishihara H., Maechler P., Wollheim C.B. Islet beta-cell secretion determines glucagon release from neighboring alpha-cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:330–335. doi: 10.1038/ncb951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wijesekara N., Chimienti F., Wheeler M.B. Zinc, a regulator of islet function and glucose homeostasis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2009;11(Suppl 4):202–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brelje T.C., Scharp D.W., Sorenson R.L. Three-dimensional imaging of intact isolated islets of Langerhans with confocal microscopy. Diabetes. 1989;38:808–814. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.6.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocheleau J.V., Piston D.W. Chapter 4: Combining microfluidics and quantitative fluorescence microscopy to examine pancreatic islet molecular physiology. Methods Cell Biol. 2008;89:71–92. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)00604-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berclaz C., Pache C., Lasser T. Combined Optical Coherence and Fluorescence Microscopy to assess dynamics and specificity of pancreatic beta-cell tracers. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:10385. doi: 10.1038/srep10385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimmermann T., Rietdorf J., Pepperkok R. Spectral imaging and its applications in live cell microscopy. FEBS Lett. 2003;546:87–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinclair M.B., Haaland D.M., Jones H.D. Hyperspectral confocal microscope. Appl. Opt. 2006;45:6283–6291. doi: 10.1364/ao.45.006283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lansford R., Bearman G., Fraser S.E. Resolution of multiple green fluorescent protein color variants and dyes using two-photon microscopy and imaging spectroscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2001;6:311–318. doi: 10.1117/1.1383780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao L., Kester R.T., Tkaczyk T.S. Snapshot Image Mapping Spectrometer (IMS) with high sampling density for hyperspectral microscopy. Opt. Express. 2010;18:14330–14344. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.014330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao L., Kester R.T., Tkaczyk T.S. Compact Image Slicing Spectrometer (ISS) for hyperspectral fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Express. 2009;17:12293–12308. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.012293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott A.D., Gao L., Tkaczyk T.S. Real-time hyperspectral fluorescence imaging of pancreatic β-cell dynamics with the image mapping spectrometer. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:4833–4840. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao L., Bedard N., Tkaczyk T.S. Depth-resolved image mapping spectrometer (IMS) with structured illumination. Opt. Express. 2011;19:17439–17452. doi: 10.1364/OE.19.017439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huisken J., Swoger J., Stelzer E.H.K. Optical sectioning deep inside live embryos by selective plane illumination microscopy. Science. 2004;305:1007–1009. doi: 10.1126/science.1100035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keller P.J., Schmidt A.D., Stelzer E.H.K. Fast, high-contrast imaging of animal development with scanned light sheet-based structured-illumination microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:637–642. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santi P.A. Light sheet fluorescence microscopy: a review. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2011;59:129–138. doi: 10.1369/0022155410394857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahou P., Vermot J., Supatto W. Multicolor two-photon light-sheet microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:600–601. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jahr W., Schmid B., Huisken J. Hyperspectral light sheet microscopy. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7990. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Y., Ghitani A., Shroff H. Inverted selective plane illumination microscopy (iSPIM) enables coupled cell identity lineaging and neurodevelopmental imaging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:17708–17713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108494108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Marchand S.J., Piston D.W. Glucose suppression of glucagon secretion: metabolic and calcium responses from alpha-cells in intact mouse pancreatic islets. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:14389–14398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.069195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luche H., Weber O., Fehling H.J. Faithful activation of an extra-bright red fluorescent protein in “knock-in” Cre-reporter mice ideally suited for lineage tracing studies. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007;37:43–53. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herrera P.L. Adult insulin- and glucagon-producing cells differentiate from two independent cell lineages. Development. 2000;127:2317–2322. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benninger R.K., Zhang M., Piston D.W. Gap junction coupling and calcium waves in the pancreatic islet. Biophys. J. 2008;95:5048–5061. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.140863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Easley C.J., Rocheleau J.V., Piston D.W. Quantitative measurement of zinc secretion from pancreatic islets with high temporal resolution using droplet-based microfluidics. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:9086–9095. doi: 10.1021/ac9017692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kester R.T., Gao L., Tkaczyk T.S. Development of image mappers for hyperspectral biomedical imaging applications. Appl. Opt. 2010;49:1886–1899. doi: 10.1364/AO.49.001886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bedard N., Hagen N., Tkaczyk T.S. Image mapping spectrometry: calibration and characterization. Opt. Eng. 2012;51:111711. doi: 10.1117/1.OE.51.11.111711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zimmermann T. Spectral imaging and linear unmixing in light microscopy. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2005;95:245–265. doi: 10.1007/b102216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Y., Wawrzusin P., Shroff H. Spatially isotropic four-dimensional imaging with dual-view plane illumination microscopy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:1032–1038. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foster M.C., Leapman R.D., Atwater I. Elemental composition of secretory granules in pancreatic islets of Langerhans. Biophys. J. 1993;64:525–532. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81397-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gyulkhandanyan A.V., Lee S.C., Wheeler M.B. The Zn2+-transporting pathways in pancreatic β-cells: a role for the L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:9361–9372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le Marchand S.J., Piston D.W. Glucose decouples intracellular Ca2+ activity from glucagon secretion in mouse pancreatic islet alpha-cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moerner W.E. Single-molecule mountains yield nanoscale cell images. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:781–782. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1006-781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prost A.L., Bloc A., Vivaudou M. Zinc is both an intracellular and extracellular regulator of KATP channel function. J. Physiol. 2004;559:157–167. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.065094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Villareal D.T., Koster J.C., Polonsky K.S. Kir6.2 variant E23K increases ATP-sensitive K+ channel activity and is associated with impaired insulin release and enhanced insulin sensitivity in adults with normal glucose tolerance. Diabetes. 2009;58:1869–1878. doi: 10.2337/db09-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davidson H.W., Wenzlau J.M., O’Brien R.M. Zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8) and β cell function. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;25:415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Truong T.V., Supatto W., Fraser S.E. Deep and fast live imaging with two-photon scanned light-sheet microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:757–760. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lavagnino Z., Zanacchi F.C., Diaspro A. Two-photon excitation selective plane illumination microscopy (2PE-SPIM) of highly scattering samples: characterization and application. Opt. Express. 2013;21:5998–6008. doi: 10.1364/OE.21.005998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lavagnino Z., Sancataldo G., Cella Zanacchi F. 4D (x-y-z-t) imaging of thick biological samples by means of Two-Photon inverted Selective Plane Illumination Microscopy (2PE-iSPIM) Sci. Rep. 2016;6:23923. doi: 10.1038/srep23923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.