Abstract

Cardiac optical mapping uses potentiometric fluorescent dyes to image membrane potential (Vm). An important limitation of conventional optical mapping is that contraction is usually arrested pharmacologically to prevent motion artifacts from obscuring Vm signals. However, these agents may alter electrophysiology, and by abolishing contraction, also prevent optical mapping from being used to study coupling between electrical and mechanical function. Here, we present a method to simultaneously map Vm and epicardial contraction in the beating heart. Isolated perfused swine hearts were stained with di-4-ANEPPS and fiducial markers were glued to the epicardium for motion tracking. The heart was imaged at 750 Hz with a video camera. Fluorescence was excited with cyan or blue LEDs on alternating camera frames, thus providing a 375-Hz effective sampling rate. Marker tracking enabled the pixel(s) imaging any epicardial site within the marked region to be identified in each camera frame. Cyan- and blue-elicited fluorescence have different sensitivities to Vm, but other signal features, primarily motion artifacts, are common. Thus, taking the ratio of fluorescence emitted by a motion-tracked epicardial site in adjacent frames removes artifacts, leaving Vm (excitation ratiometry). Reconstructed Vm signals were validated by comparison to monophasic action potentials and to conventional optical mapping signals. Binocular imaging with additional video cameras enabled marker motion to be tracked in three dimensions. From these data, epicardial deformation during the cardiac cycle was quantified by computing finite strain fields. We show that the method can simultaneously map Vm and strain in a left-sided working heart preparation and can image changes in both electrical and mechanical function 5 min after the induction of regional ischemia. By allowing high-resolution optical mapping in the absence of electromechanical uncoupling agents, the method relieves a long-standing limitation of optical mapping and has potential to enhance new studies in coupled cardiac electromechanics.

Introduction

Cardiac optical mapping is widely used in cardiac electrophysiology research. In optical mapping, voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes convert changes in membrane potential (Vm) to changes in emitted fluorescence intensity that can be recorded with high-speed photodetectors (e.g., charge-coupled device (CCD) or complementary metal-oxide semiconductor cameras). Optical mapping has several advantages relative to electrical mapping, a technique in which extracellular potentials are recorded from arrays of electrodes. For example: 1) higher spatial resolution allows propagation patterns during complex arrhythmias to be imaged with better detail; 2) insensitivity to high-voltage shocks enables the modulation of cardiac electrical activity by defibrillation shocks to be imaged; and 3) proportionality to Vm rather than to extracellular potentials means optical signals contain both activation and repolarization information and are better suited to understanding reentrant arrhythmias (1).

A key limitation of conventional cardiac optical mapping is that motion of the imaged tissue causes artifacts that swamp Vm signals. A common approach to address this issue is to use pharmacologic agents that arrest mechanical contraction but preserve electrical activity. However, such agents have drawbacks, including: altering the electrophysiological properties of myocardium (2, 3, 4); changing the heart’s metabolic demands (5, 6); and, importantly, reducing or eliminating contraction, which precludes the study of interactions between the heart’s electrophysiology and mechanical function.

Some methods have been developed for optically mapping Vm in contracting preparations. Ratiometry uses multiple excitation (7) or emission (8) wavelengths to correct motion artifacts and is sometimes effective. Motion artifacts can also be at least partially corrected using image registration techniques (9). Using ratiometry together with motion tracking has shown promise for recording Vm optically in beating-heart preparations (10, 11).

Using motion tracking as part of a Vm mapping scheme has the additional benefit of quantifying the regional deformation of contracting hearts, enabling study of electromechanical coupling. This coupling is bidirectional: electrical waves trigger contraction, and mechanical stretch can influence Vm (12). Previous animal and computational studies have shown that mechanical stretch can open stretch-activated channels causing membrane depolarization that may contribute to arrhythmogenesis (13, 14).

The objective of this study is to develop an optical mapping system for beating hearts. Vm is mapped across the epicardium with high spatial resolution, making the method suitable for spatially complex arrhythmias. At the same time, the epicardium is reconstructed in three dimensions (3D) so that measurements of cardiac contraction and deformation are insensitive to motion out of the camera plane. Together, these features provide a new, to our knowledge, tool for investigating the bidirectional coupling between cardiac electrical and mechanical function.

Materials and Methods

Heart preparation

We studied a total of 12 isolated hearts from pigs of either sex, weighing 22–39 kg. Three of the hearts were perfused in Langendorff mode and were used to record fluorescence emission spectra. Six additional hearts were Langendorff-perfused and were used to map Vm in a beating preparation. The remaining three hearts were perfused with a left ventricular (LV) working apparatus and were used for simultaneous mapping of Vm and quantification of epicardial deformation. Heart preparation, perfusion and staining are detailed in the Supporting Material (S1. Heart Preparation, Perfusion and Staining). In the nine hearts not used for emission spectra, ∼20 black circular markers punched from polyethylene film (2 mm diameter, ∼8 mm spacing) were glued to the anterior left ventricular epicardium with tissue adhesive (1469SB, 3M Vetbond; 3M, Maplewood, MN). Once defibrillated, the hearts beat spontaneously or were paced with basic cycle length (BCL) from 250 to 1000 ms.

Instrumentation

Voltage-sensitive dyes such as di-4-ANEPPS work by shifting their absorption and emission spectra in response to changes in Vm. This modulates the intensity of emitted fluorescence that is registered at the photodetector. Both the polarity and amplitude of Vm-dependent fluorescence intensity changes can be manipulated by choice of excitation light wavelength as well as the band of emission light that is recorded (15, 16). Our optical mapping system employs excitation ratiometry. In this scheme, the wavelength of excitation light is switched with every camera frame and a single band of emitted fluorescence is recorded (7, 10). The principle is that motion artifacts are not dependent on excitation wavelength, but Vm is. Therefore, taking the ratio of signals derived from adjacent frames cancels artifacts while preserving Vm.

The excitation light wavelengths we used (blue, 450 nm; cyan, 505 nm) were selected based on the following considerations: 1) both are near the peak of di-4-ANEPPS’s absorption spectra and efficiently elicit fluorescence, but are sufficiently far apart to produce differing Vm sensitivity; 2) both are commercially available in a high-power, small-footprint LED format (Luxeon Z; Lumileds, San Jose, CA), and LEDs are advantageous for fast color switching; and 3) both are sufficiently far from the emission band to allow effective filtering of reflected excitation light. The spectra of the LEDs are shown in Fig. S2 in the Supporting Material.

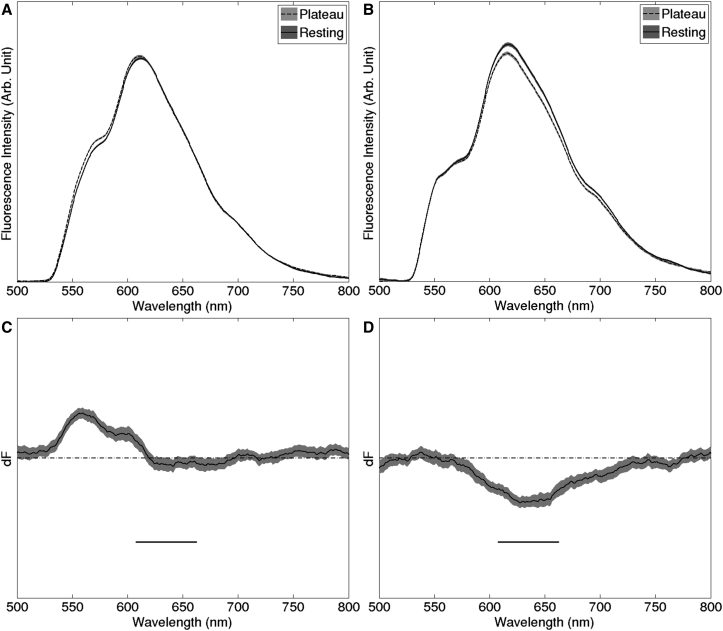

Our emission band was selected from analysis of emission difference spectra recorded from three hearts. Difference spectra show the difference in light emitted during rest and plateau (Fig. 1; see S2. Acquisition of Di-4-ANEPPS Emission Difference Spectra for spectra acquisition details). For a particular excitation wavelength, Vm sensitivity is maximized by recording an emission band near the peak of the difference spectrum and is minimized by recording near a zero-crossing (isosbestic point). The horizontal bars in Fig. 1, C and D, indicate the emission band we selected (635 ± 27.5 nm). Cyan-elicited fluorescence in this band has strong Vm sensitivity, while blue-elicited fluorescence has very little Vm sensitivity.

Figure 1.

Selection of emission band. (A and B) Emission spectra recorded during action potential plateau and during rest for blue (450 nm) and cyan (505 nm) excitation, respectively. (C and D) Difference spectra obtained by subtracting the resting from plateau spectra from (A) and (B), respectively. Horizontal bars in (C) and (D) indicate the passband of the emission filter (635 ± 27.5 nm). Plots in (C) and (D) have the same vertical scale. The emission spectra are averages; the gray bands show the 95% confidence intervals for the spectra.

Fig. 2 shows the components of the mapping system. Excitation light is produced by high-power LEDs mounted in four custom-built water-cooled illumination units (Fig. S1) that are mounted on the four sides of the mapping camera lens, ∼15 cm away from the epicardium. In excitation ratiometry, it is important that the ratio of the intensity of the two excitation colors is spatially uniform (see Appendix A). We estimated the heterogeneity of the intensity ratio by moving the end of a fiber optic spectrometer probe at approximately constant speed in a sinusoidal pattern through the region of the illumination field normally occupied by the heart. Both LED colors were turned on and spectra were continuously sampled. The intensity ratio at each site was computed as the ratio of the blue to cyan peaks. This was done first for each of the four light units individually. The intensity ratios were: 1.645 ± 0.007, 1.769 ± 0.004, 1.584 ± 0.003, and 1.699 ± 0.004. The small SDs indicate that color mixing within units is effective and each produces a light field with homogeneous intensity ratio. Repeating the experiment with all units turned on gives a ratio of 1.65 ± 0.03. The increased heterogeneity is a result of differences across light units.

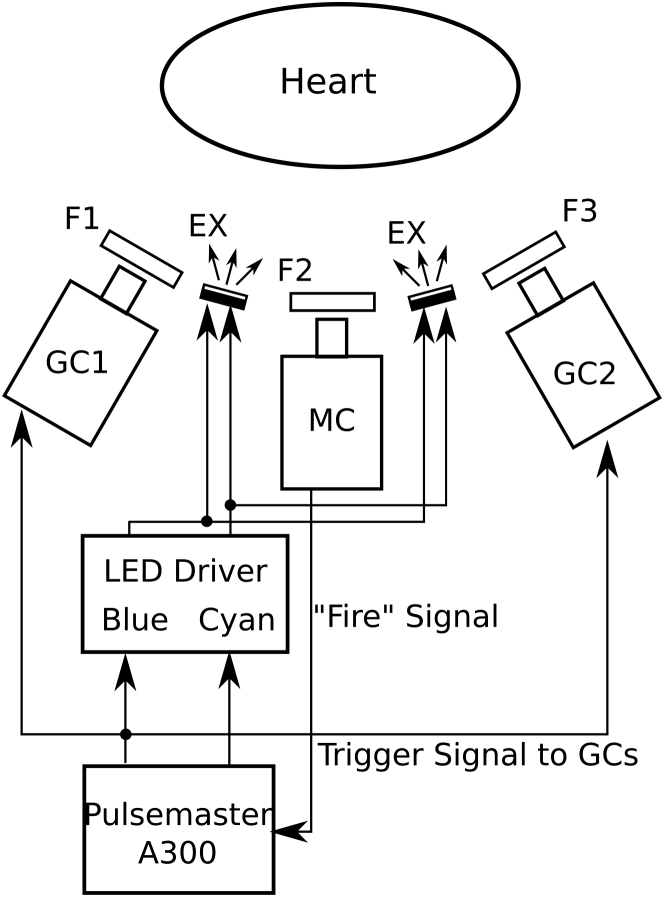

Figure 2.

Optical mapping system with two geometry cameras. MC, mapping camera; GC1 and GC2, geometry cameras; F1 and F3, emission filter (590-nm long-pass filter); F2, emission filter (635 ± 27.5-nm band-pass filter). EX, excitation light source units (see Figs. S1 and S2). “Fire” is a digital pulse marking the start of each MC frame.

The emitted fluorescence is recorded with a high-speed CCD camera (i.e., the mapping camera; iXon DV-860DC-BV; Andor Technology, Windsor, CT) at 750 fps with 128 × 64 resolution. The camera is fitted with a 6 mm/f1.0 lens (QS610; Pentax, Tokyo, Japan). The LEDs are driven with custom-made circuits whose on-off state can be controlled with digital pulses. A pulse generator (Pulsemaster A300; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) is synchronized to the start of exposure of each mapping camera frame and programmed so that odd frames trigger the blue LEDs and even frames trigger the cyan LEDs. Thus, video files are interlaced with odd frames containing blue-elicited fluorescence and even frames containing cyan-elicited fluorescence.

Epicardial deformation is recorded in 3D with additional cameras (i.e., the geometry cameras, Genie HM640; Teledyne DALSA, Billerica, MA; Fig. 2). The cameras are fitted with 6 mm/f1.0 lenses (QS610; Pentax) and 590-nm long-pass filters. Two or more geometry cameras are mounted adjacent to the mapping camera for binocular imaging of the epicardial markers. These cameras are set to 320 × 375 resolution and synchronized to odd (blue) mapping camera frames; thus the geometry camera frame rate is 375 Hz.

Experimental procedure

After the hearts were mounted in the perfusion apparatus, the cameras were aimed at the marked epicardial region and focused. Multiple runs (∼4 s duration each) were recorded. To quantitatively validate Vm signals, in three Langendorff-perfused hearts, we simultaneously recorded monophasic action potential (MAP) signals (see S3. Epicardial Monophasic Action Potential Recording for detail). The geometry cameras were not used during these runs because the MAP probe would obscure one camera’s view of the heart.

In a subset of experiments, after recording data from beating hearts, an electromechanical uncoupling agent was added to the perfusate (butanedione monoxime (BDM) 20 mmol/L, 2 hearts or blebbistatin, 20 μmol/L, 1 heart). These agents prevent contraction without arresting cardiac electrical activity and are commonly used in conventional optical mapping experiments. Additional runs were recorded with the heart either stationary or moved manually.

In experiments in which the geometry cameras were used, after all data runs were recorded, the heart was replaced by a cylindrical calibration target (Fig. S3) that was imaged by all cameras.

Data processing

Tissue motion tracking

Optically recording the membrane potential from an epicardial site in a beating heart requires the position of that site within the image plane to be known in each video frame. In a previous publication, we tracked discrete sites by marking them with ring-shaped markers and collecting signal from the circumscribed tissue (10). In that method, spatial resolution was limited by the number of marker rings (on the order of 10 in that publication). In this method, we use dot-shaped markers, and membrane potential signals can be acquired from all sites within the marked region except those obscured by markers. Thus, spatial resolution is improved by orders of magnitude and approaches that of the camera.

All the following data processing procedures are done with MATLAB (2013a; The MathWorks, Natick, MA). Epicardial markers imaged by the mapping or geometry cameras are tracked with a two-dimensional (2D) Gaussian fitting method. For each marker: (1) the estimated center of the marker in the first camera frame is identified manually; (2) a subimage centered on the estimated center and containing only the target marker is extracted; (3) the subimage is inverted and a 2D Gaussian function is fitted to the pixel intensity values; (4) the maximum of the Gaussian function is taken as the center of the marker (i.e., the fitted center). This method finds marker centers with subpixel accuracy even when the angle of the marker with respect to the camera makes the marker appear elliptical. The fitted center is used as the initial estimated center for Gaussian fitting on the next frame, and steps 2–4 are repeated until reaching the last frame of the video.

We define trackable markers as those that remain visible to the mapping camera for the entire acquisition. Because of cardiac motion, visibility can be lost periodically for markers near the edge of the camera frame or near the edge of the heart’s silhouette. Only trackable markers are used in further data processing.

For the mapping cameras, to avoid errors caused by different fluorescent intensities on even and odd frames, Gaussian fitting is done only on odd frames, and marker locations for even frames are estimated by averaging marker coordinates from the two adjacent frames. For all cameras, after marker tracking, the fitted center coordinates for each marker are filtered with a 7-point temporal median filter. Fitted center coordinates for the first frame are saved and the center coordinates for all subsequent frames are converted to displacement vectors relative to the first frame (see Appendix A and Fig. S4).

We use the mapping camera marker data to track the motion of epicardial sites across the mapping camera image plane. Consider an epicardial site that is imaged by a pixel in the first frame and the triangle formed by the three markers that surround that site. As the triangle deforms and moves across the image plane as a result of cardiac motion, if we assume that the triangle is small enough that deformation is homogeneous within the triangle (see Epicardial Marker Spacing below), then the coordinates (local to the triangle) of the epicardial site are constant. In each frame, we linearly interpolate the displacement vectors measured at the markers forming the triangle. This interpolated displacement is applied to the epicardial site to find its position relative to its first-frame position for all subsequent frames (Fig. S5). In this way, we can track the trajectory across the image plane of all epicardial sites within the marked region. Using the trajectory, we generate a signal containing the fluorescence emitted by each site.

Epicardial marker spacing

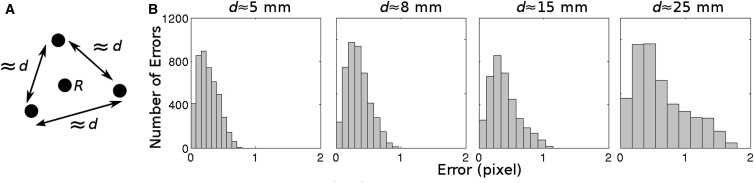

Our motion tracking method assumes that deformation is homogeneous within marker triangles so that linear interpolation of marker displacement is adequate to track epicardial sites within triangles. This is valid if marker spacing is sufficiently small (17); however, excessive marker density is undesirable because of the time required to place and process the markers as well as the epicardial area that would be obscured. To determine optimal spacing, we attached markers to the anterior LV epicardium of a pig heart perfused in LV working mode. Marker spacing was either d = 5, 8, 15, or 25 mm. A fourth marker was placed at the approximate center of each triangle used for this analysis (Fig. 3 A, marker R). The four markers associated with a triangle were tracked as described above for 3000 camera frames during paced rhythm. In addition, the centroid of marker R was identified in the first frame and its trajectory through the remaining frames was estimated using linear interpolation of the three surrounding marker positions as described above. Fig. 3 B shows histograms of the distance error between the measured and interpolated positions of the centroid of R. With d ≤ 8 mm, almost all errors were well under 1 pixel and 8 mm was chosen for our standard spacing. However, spacing up to ∼15 mm will likely yield similar results.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of motion tracking with different marker spacings. (A) Pattern of marker placement. (B) Histograms of distance error with different marker spacings. Distance error is defined as the distance (in pixels) between the estimated image coordinates of site R and the actual image coordinates of site R.

Ratiometric reconstruction of membrane potential signals

To obtain a Vm signal from the fluorescence signal that is emitted by a motion-tracked epicardial tissue site, we first subtract a constant offset from each sample (the intensity registered by a pixel when the camera is not exposed to light). Next, we deinterlace the fluorescence signal into its blue- and cyan-elicited components (odd and even samples, respectively). The principle of excitation ratiometry is that while voltage sensitivity differs for the two excitation wavelengths, fluorescence deflections from other sources (i.e., motion artifacts) are common. We therefore cancel the common artifacts by dividing each odd sample by the average of the two adjacent even samples. See Appendix A for details. The resulting signal is related to Vm by a constant offset and scale factor and action potentials are upright. It has a temporal resolution of 375 Hz, which is one-half the mapping camera frame rate.

3D surface reconstruction

We use binocular data from one or more geometry camera pairs (e.g., GC1 and GC2 in Fig. 2) to reconstruct a 3D model of the beating epicardial surface. We calibrate all cameras by imaging a cylindrical calibration target with a known pattern of marks (Fig. S3). After recording fluorescence data, we replace the heart with the calibration target and image it with all cameras. For each camera, we use a custom MATLAB program (The MathWorks) to manually select image coordinates of visible calibration points and pair them with their known 3D world coordinates relative to the calibration target. The world coordinate system is a right-handed Cartesian system with its origin at the target’s centroid and its Z axis parallel to the target’s longitudinal axis (approximately parallel to the heart’s base-apex axis). The orientation of the X and Y axes depends on target placement, and is arbitrary. The marker coordinates are passed to a MATLAB program that uses the method of Heikkilä et al. (18) to compute a camera model (see S4. Camera Model). The camera model corrects lens distortions and enables points in a camera image to be projected through the lens focal point to a sightline through the 3D World Coordinate System. To find the 3D World Coordinates of an epicardial marker in any given camera frame, we compute sightlines from the marker’s centroid in two geometry camera views. The marker’s 3D coordinates are given by the point of nearest approach of the two sightlines (noise and computational error make exact intersection unlikely).

Because of the curvature of the heart, a single pair of geometry cameras flanking the mapping camera (as shown in Fig. 2) may not provide adequate binocular views of all markers in the mapped region. One alternative configuration is to position a third geometry camera above the mapping camera to provide two additional geometry camera pairs. In such multipair configurations, each marker is assigned to one binocular pair.

Quantification of epicardial deformation

We employ a variant of previous methods (17, 19) to quantify cardiac mechanical contraction. The assumption of homogeneous deformation is valid (see Epicardial Marker Spacing above), so tissue deformation is described with homogeneous strain theory, which assumes uniform strain within each mesh triangle. The method is similar to that described by Meier et al. (17). Briefly, the 3D coordinates of usable markers are projected to the surface of a cylinder and triangulated in 2D using Delaunay triangulation, forming a 3D triangle mesh. In each of these triangles, a local 2D Cartesian coordinate system (X′, Y′) is created in the plane of the triangle with its origin located at the triangle’s centroid. The two axes are tangent to the epicardium; X′ is normal to the World Coordinate System Z axis (which is approximately parallel to the base-apex axis), and Y′ is normal to X′. The 3D marker coordinates are transformed to these local 2D coordinates and the following analysis is done in that system: The state at end-diastole is used as the reference for strain calculations. End-diastole is identified by the time when the triangle area is maximal; in experiments in which tissue dysfunction obscures the local mechanical diastole, we instead use the time immediately preceding the upstroke in simultaneously recorded Vm signals. Using the method described by McCulloch et al. (19), the mechanical deformation is quantified with a deformation gradient tensor F that can be uniquely separated into a rotation tensor R and a stretch tensor U (polar decomposition). The eigenvalues of U indicate the shortening or stretching of each triangle relative to end-diastole in the major and minor deformation directions. The eigenvectors of U give the major and minor directions (Fig. S6).

Results

Membrane potential measurement

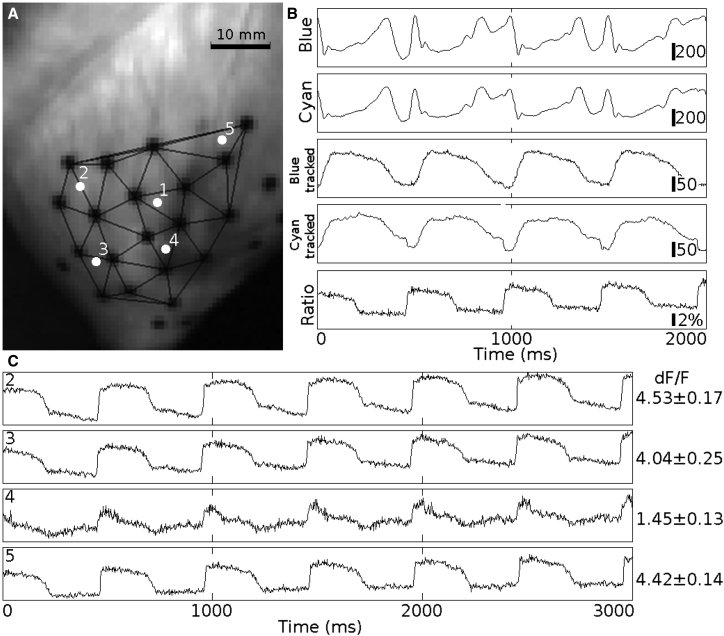

Fig. 4 shows example fluorescence signals from a Langendorff-perfused beating heart paced at 500 ms BCL. There were 25 markers on the epicardium, 19 of which were trackable throughout the entire data run (Fig. 4 A). Fluorescence signals were spatially filtered by an averaging filter with a 2-pixel-radius disk-shaped window and then deinterlaced into blue- and cyan-elicited signals (Fig. 4 B, top four traces). The top two traces in Fig. 4 B are the deinterlaced blue-/cyan-elicited signals recorded from the fixed pixel where epicardial site 1 was located in the first video frame. The third and fourth traces (blue tracked/cyan tracked) show the signals associated with epicardial site 1 after motion tracking. The motion artifacts were significantly suppressed with motion tracking. The cyan-elicited signals contain both membrane potential signal and motion artifacts, whereas the blue-elicited signals contain primarily motion artifacts. Taking the ratio of the tracked blue- and cyan-elicited signals cancels most motion artifacts and produces an upright Vm signal (Fig. 4 B, bottom signal). The fractional fluorescence (dF/F) of the cyan-elicited signal at this site is 4.01 ± 0.18% (mean ± SD, computed from eight individual action potentials after arresting contraction with BDM; dF/F is the Vm-related fluorescence change divided by background fluorescence). The quality of Vm reconstruction varies from site to site. Fig. 4 C shows examples of reconstructed Vm signals and cyan-elicited dF/F from sites 2 to 5. The darker area on the right side of Fig. 4 A has poor staining relative to other regions. Site 4, within this region, has low dF/F (1.45 ± 0.13%), which results in a poor signal reconstruction. The Vm signals at some sites exhibit noticeable residual motion artifacts (e.g., altered baseline after repolarization at site 2).

Figure 4.

Vm reconstruction on a Langendorff-perfused beating heart. The heart was paced at 500 ms BCL from the LV subepicardium near the apex. (A) Triangulation of trackable markers and location of epicardial sites. The signals in (B) are from epicardial site 1. Blue/cyan: deinterlaced blue- and cyan-elicited signals from the pixel where site 1 is located at the first frame, after spatial filtering. Blue tracked/cyan tracked: deinterlaced blue- and cyan-elicited signals, respectively, after motion tracking and spatial filtering. The bars are CCD signal counts (proportional to fluorescence intensity). Ratio: the motion-corrected Vm signal is the ratio of the blue- to cyan-elicited signals. The bar is dF/F. (C) Reconstructed Vm signals and dF/F from sites 2–5, respectively.

Movie S1 in the Supporting Material animates spatiotemporal patterns of electrical activation and repolarization in a beating heart obtained by reconstructing Vm signals at all pixels in the tracked region.

Reconstructed Vm signals were validated by comparison with signals obtained with conventional optical mapping (i.e., no motion tracking or ratiometry) after treatment with blebbistatin. Blebbistatin is an electromechanical uncoupling agent thought to have minimal effects on action potential morphology (20). Fig. S7 shows an example. Action potential morphology is very similar for the two signals, which were taken from the same epicardial site.

Reconstructed Vm signals were validated quantitatively by comparing action potential durations (APD) with APDs from simultaneously recorded MAP signals. The MAP electrode was placed adjacent to the marked epicardial region because placing it inside the region would obscure the mapping camera’s view and prevent acquisition of optical signals. To minimize site-to-site APD differences, Vm signals to be compared with the MAP signals were collected from the unobscured sites closest to the MAP probe (always within 2 cm). MAP data were decimated to the same sampling rate as the optical signals (375 Hz). APDs were computed with a method similar to that introduced by Efimov et al. (21). Briefly, the reconstructed membrane potential signal was filtered with a temporal median filter (n = 15) and its first and second derivatives were computed with a 15-point, third-order Savitzky-Golay filter. Depolarization was detected by finding the first derivative peaks (which coincide with action potential upstrokes). Repolarization was detected by finding the maximum second derivative peak in a local window that was defined by the interval between two depolarization upstrokes (from 80 ms after the depolarization to 80 ms before the next depolarization). APD was defined as the time between the depolarization and repolarization (Fig. S8). Because repolarization time is defined by an inflection in the rapidly changing Vm signal, APD computed in this way is relatively insensitive to the slow shifts typical of residual motion artifacts.

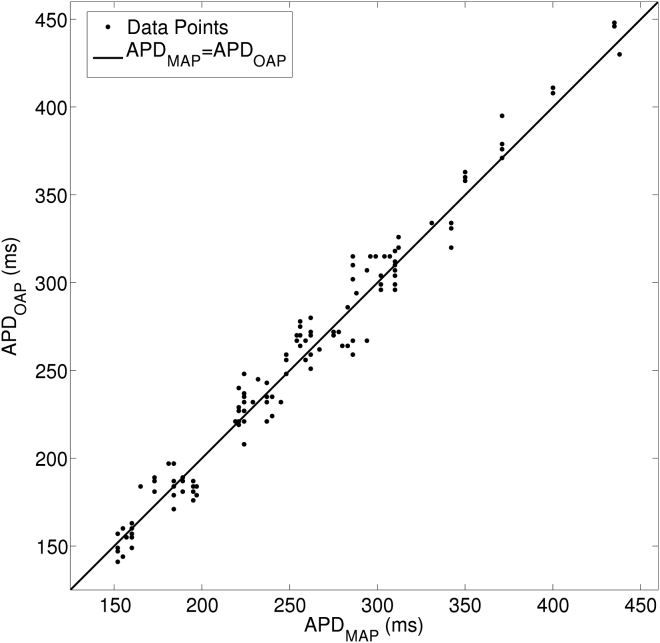

In three Langendorff-perfused hearts, we recorded spontaneous beats and beats paced from 250- to 1000-ms cycle length. Each activation rate produces different cardiac motion and action potential morphology and therefore challenges Vm reconstruction in a different way. We therefore treated each rate/heart combination as an independent state. There were 17 states and 7.4 ± 4.4 replicated action potentials per state. We used a linear mixed-effects model (MIXED procedure, SPSS rel. 22; IBM, Armonk, North Castle, NY) to do a paired comparison of APDs from the MAP and Vm signals within each state. There was not a significant difference (p = 0.17). Fig. 5 is a scatter plot of APDs computed from simultaneous optical and MAP recordings.

Figure 5.

APDs of monophasic action potential (APDMAP) and reconstructed optical Vm (APDOAP). In three Langendorff-perfused hearts, MAP and Vm signals were simultaneously recorded at different spontaneous or paced activation rates. One-hundred-thirty activations from a total of 23 MAP-Vm site-pairs were analyzed. MAP-Vm site separation was <2 cm in all cases.

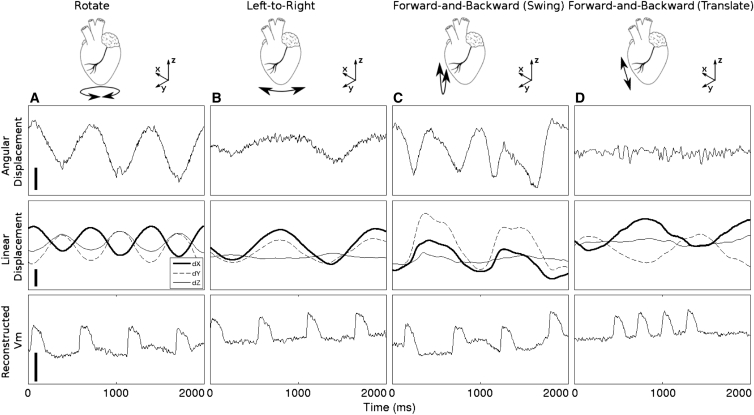

To investigate the relationship between tissue motion and residual motion artifacts such as those in Fig. 4, we analyzed runs from two Langendorff-perfused hearts in which both epicardial geometry and Vm were recorded after BDM treatment to arrest contraction. In these data runs, tissue motion was induced manually by: 1) swinging the hearts forward-and-backward relative to the camera, 2) swinging the hearts left-to-right relative to the camera, 3) twisting the heart about its vertical axis, or 4) translating the heart toward and away from the camera. Motion was therefore decoupled from electrical activity. An epicardial site in the center of the mapped region together with its three surrounding markers was selected. Motion was characterized 1) by the angle of the site’s surface normal vector relative to the camera’s optical axis and 2) the 3D displacement of the site. Fig. 6 shows examples of angular motion, linear motion, and reconstructed membrane potential signals resulting from the four different motion types. In general, motion artifacts are best corrected when there is minimal angular motion.

Figure 6.

Reconstructed Vm signals in the setting of manually induced motion in a heart treated with BDM. Residual motion artifacts are apparent as shifts of Vm baseline. Angular displacement indicates the angle between the local surface normal vector and the optical axis of the mapping camera. Linear displacement indicates 3D displacement of the recording site. (Column A) The heart was rotated about its vertical axis. (Column B) The heart was swung from left-to-right relative to the camera. (Column C) The heart was swung forward and backward relative to the camera. (Column D) The heart was translated forward and backward in the direction parallel to optical axis of the camera. The calibration bars represent 2.5°, 5 mm, and 5%, respectively.

3D surface reconstruction and mechanical contraction measurement

The accuracy of the 3D epicardial surface reconstruction depends largely on the systematic error of the binocular image system. This error was measured with a known target, printed with markers the same size as those used on the heart, and placed with 10 mm pitch. The target was placed in different positions within the fields of view of the geometry cameras. Marker positions were reconstructed and the distances between 30,000 marker pairs were computed. The maximum distance error was 0.19 mm and mean error was 0.04 ± 0.06 mm.

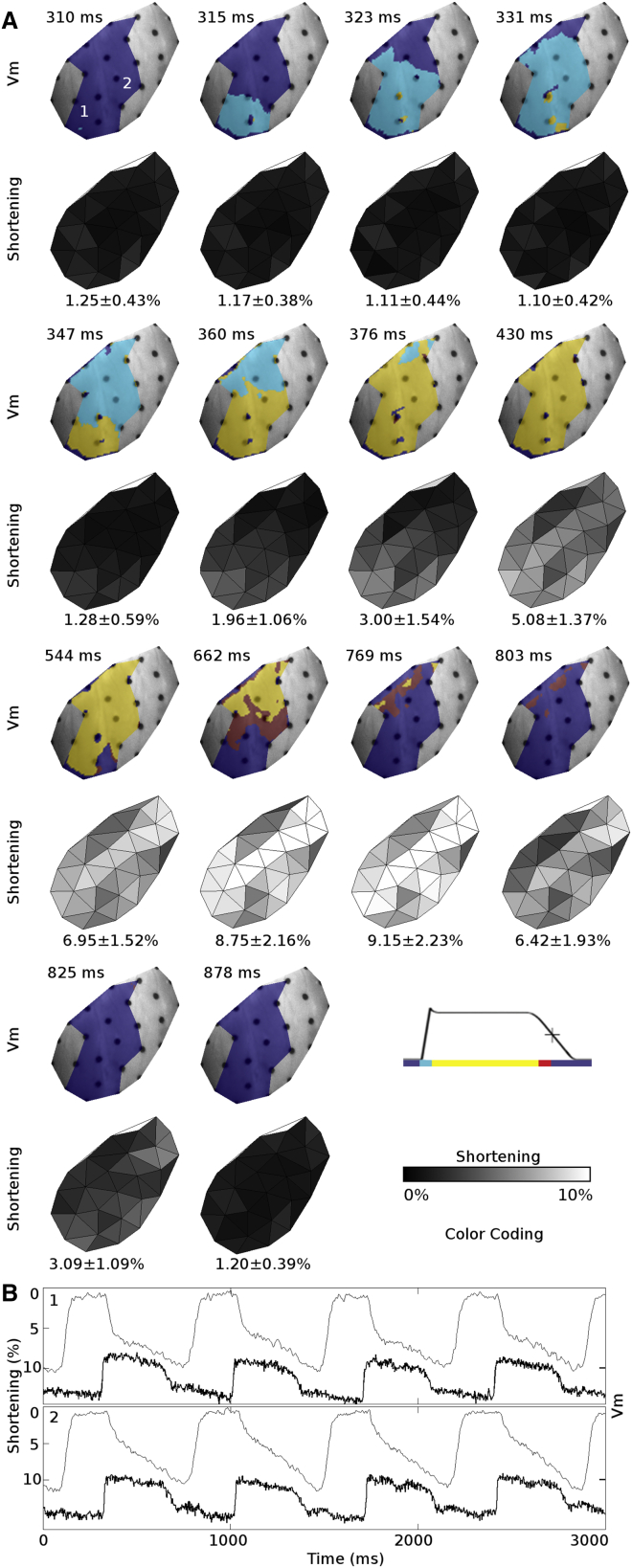

We mapped epicardial deformation simultaneously with electrical function in three LV working heart preparations. In these studies, we positioned a third geometry camera above the mapping camera to provide a wider binocular field of view (see 3D Surface Reconstruction, above). Fig. 7 and Movie S2 show an example of the reconstructed 3D epicardial surface model with the simultaneously recorded Vm signals and mechanical contraction. End-systolic deformations of the LV anterior epicardium from all LV-working hearts are shown in Table 1. All hearts were paced from the LV apex. End-systolic deformation was quantified with principal strains. The major deformation direction is the direction of greatest shortening and the minor deformation direction is the orthogonal direction in the local epicardial plane. Overall, end-systolic shortening in the major deformation direction was 9.22 ± 2.73% and the tissue expanded 0.34 ± 1.15% in the minor deformation direction. End-systolic shortening decreased as heart rate increased.

Figure 7.

Simultaneously recorded Vm and mechanical contraction from an LV working heart. (A) Action potential propagation (upper rows) and the resulting mechanical contraction (lower rows) from a single beat. Regions in which Vm is unavailable are colored gray. (B) Mechanical contraction (fine line) and the simultaneously recorded Vm signal (bold line) from sites 1 and 2 in (A). The spatial average of shortening is reported at the bottom of each shortening map. Shortening is defined as the most negative eigenvalue of the stretch tensor, U. The heart was paced from the LV apex at 700 ms BCL, and LV preload and afterload pressures were set to 15 and 30 mmHg, respectively.

Table 1.

End-systolic LV Epicardial Principal Strains

| Animal number | Preload pressure (mmHg) | Afterload pressure (mmHg) | Basic cycle length (ms) | Available triangles | End-systolic deformation (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major | Minor | |||||

| 1 | 15 | 45 | 800 | 26 | −9.5 ± 1.5 | −0.7 ± 1.0 |

| 1 | 15 | 45 | 500 | 26 | −9.0 ± 1.1 | −0.2 ± 1.3 |

| 2 | 15 | 30 | 700 | 17 | −9.7 ± 3.6 | 1.0 ± 0.7 |

| 2 | 15 | 30 | 500 | 14 | −9.0 ± 3.1 | 0.8 ± 0.6 |

| 3 | 15 | 30 | 700 | 37 | −11.1 ± 2.6 | 0.2 ± 1.3 |

| 3 | 15 | 30 | 500 | 27 | −6.4 ± 1.4 | 0.8 ± 0.8 |

| Mean ± SD | 147 (total) | −9.2 ± 2.7 | 0.3 ± 1.2 | |||

End-diastole is the reference state for strain. Negative principal strain indicates shortening. All hearts were paced from the LV apex.

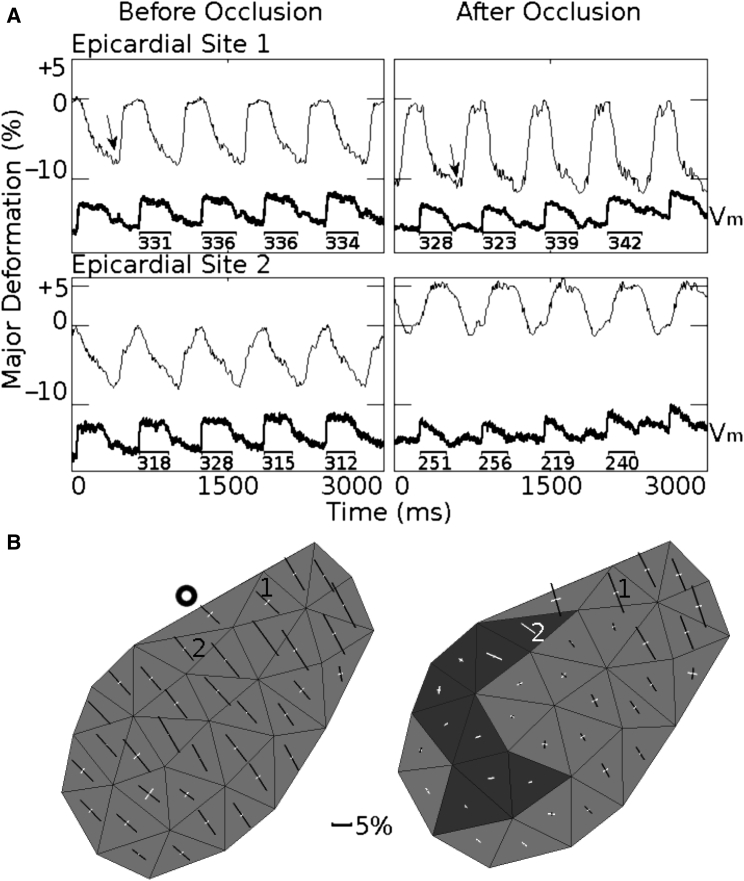

In one experiment, we placed a tie around the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) between the first and second diagonal branches to induce acute regional ischemia. Five minutes after occlusion, there were pronounced changes to both electrical and mechanical function. In the region above the occlusion, shortening and APD were minimally affected; in the ischemic zone, systolic contraction was largely abolished and APD was reduced (Fig. 8 A). Spatial details are shown in Fig. 8 B. Before occlusion (left panel), all triangles shorten in the major direction (black bars) and typically have small stretch in the orthogonal direction (white bars). After occlusion (right panel), this was still the case in perfused tissue (top right), but in ischemic tissue, strains were very small and sometimes positive in both directions (dark triangles), indicating that tissue was passively stretched by the surrounding contracting tissue and LV cavity pressure.

Figure 8.

Altered electromechanical function after coronary artery occlusion. (A) Shortening (negative deformation) or stretch (positive deformation) in the major deformation direction (thin lines) and Vm (thick lines) before and 5 min after coronary artery occlusion. Site 1 is in a perfused region adjacent to the ischemic zone and site 2 is in the ischemic zone. Numbers under Vm show the APDs in milliseconds. (B) Spatial maps of strains before and after occlusion. This is an anterior view of the LV; the base is at the top and the LAD runs along the top-left edge of the mapped region. The bold circle indicates the LAD occlusion site. The strain maps were computed for the times (end-systole) indicated by the arrows in (A). White bars indicate positive strains (stretch); black bars indicate negative strains (shortening). Bar length is proportional to stretch or shortening relative to end-diastole. The bars are oriented in the major/minor directions. End-diastole was taken as the time immediately before action potential upstroke. The heart was paced at 600 ms BCL, and LV preload and afterload pressure values were set to 15 and 30 mmHg, respectively.

Discussion

Optical mapping of membrane potential and epicardial deformation in beating hearts

Optical mapping using voltage-sensitive dyes is a widely used tool in experimental electrophysiology and has provided many important insights into cardiac propagation; for example, the role of functional reentry in tachyarrhythmias (1, 22). However, a key limitation of conventional optical mapping is that motion of the heart with respect to the photodetector induces motion artifacts that obscure Vm signals. This is usually addressed with pharmacologic electromechanical uncoupling agents that arrest contraction while preserving electrical function. There are two disadvantages to this approach: 1) uncoupling agents may alter cardiac function (2, 3, 4, 5, 6) and, perhaps more importantly, 2) electromechanical uncouplers preclude the use of optical mapping in preparations in which the heart is beating (including in vivo studies), thus preventing its use for study of subjects such as cardiac energetics or the bidirectional coupling between electrical and mechanical functions. In this article, we introduce an optical mapping method that uses 3D motion tracking and excitation ratiometry to enable Vm to be tracked with high resolution across the epicardial surface of beating hearts. At the same time, regional epicardial deformation is quantified, allowing study of the coupling between electrical and mechanical functions.

The method’s Vm signals generally have similar morphology to those recorded with conventional optical mapping (Fig. S7) and have APDs that are not different from those simultaneously recorded with an MAP electrode (Fig. 5). In normally perfused hearts, epicardial strain measured by the method averaged −9.2 ± 2.7% in the major principal direction. This shortening is consistent with epicardial strains measured in vivo by a variety of other methods in both dogs and pigs. Using biplane radiography of lead beads implanted across the wall of canine hearts, Waldman et al. (23) obtained principal epicardial strains of −10%. Similarly, using 3D MRI tagging in canine hearts, Azhari et al. (24) reported principal epicardial strains of −11 ± 5%. Hashima et al. (25) reported epicardial strains in the −10% range from biplane radiography of LV surface markers in dogs. Using similar methods, van Leuven et al. (26) reported very similar strains in pigs. Our epicardial strains in the minor principal direction were very close to 0, which is also consistent with other reports (23). After 5 min of acute ischemia, strain was preserved in perfused tissue, but in nonperfused regions, shortening was largely abolished and in places replaced with stretching in both principal directions. This is broadly consistent with van Leuven et al. (26), who after 90 min of acute ischemia, showed loss of shortening in the ischemic zone as well as systolic stretching, primarily in the circumferential direction.

Comparison with other methods

A number of motion tracking approaches have been used to address the problem of motion artifacts in beating-heart optical mapping data. Some approaches have used intrinsic image features rather than markers to spatially register sequential image frames. Rohde et al. (9) used an affine transformation to register images. Others have used a variety of nonlinear registration techniques (27, 28, 29). These methods were successful in attenuating motion artifacts in many cases; however, they were not designed to quantify mechanical deformation, which requires knowledge of the motion of material points on the epicardium (17).

Methods that have been developed to quantify cardiac motion and contraction—but without simultaneous recording of electrophysiology—include those based on biplane x-ray (17), ultrasound (30), and MRI tagging (31). Only a few methods have been developed to simultaneously image mechanical deformation and Vm; all have employed video imaging of fiducial markers. Seo et al. (11) used an array of markers attached to the mapped surface of an isolated right-ventricular preparation. They used an affine transformation to correct motion artifacts and a one-dimensional strain measurement to quantify deformation. Our group previously used an array of ring-shaped markers to collect Vm signals from ∼10 discrete sites. Our present design improves spatial resolution several-hundred-fold making it suitable for complex arrhythmias. In our previous method, local finite strains were computed using marker triangles in a manner similar to this article, but in two dimensions. With 2D motion tracking, epicardial motion must be assumed to be in the camera’s image plane, and out-of-plane motion may be misinterpreted as contraction or stretch. By tracking epicardial motion in 3D, this method computes epicardial strain correctly for general cardiac motion making the method appropriate for studying cardiac electromechanics in whole-heart preparations.

Using fiducial markers for motion tracking is advantageous because markers provide unambiguous, subpixel tracking of material points on the epicardium and are well suited to binocular, 3D motion tracking. However, marker use also has disadvantages, which include the need to attach the markers (which can be challenging in small hearts) and the small amount of epicardium that is obscured. Structured light imaging is a promising markerless approach for measuring epicardial deformation that acquires epicardial geometric data with high spatiotemporal resolution and can also estimate frame-to-frame motion of epicardial material points (32). It has potential to be integrated into an electromechanical optical mapping system, with possible disadvantages that include reduced accuracy-of-motion estimates relative to marker tracking, complexity, and the need to multiplex geometrical and Vm acquisitions.

Motion tracking ensures that a Vm signal is associated with just one myocardial site and prevents artifacts that would be caused by tissue with different effective dye concentration transiting the recording pixel. However, as a tracked site moves, local incident excitation light intensity changes, causing background fluorescence to change, thus inducing another form of motion artifact. For this reason, most motion tracking schemes also employ some other means to correct this artifact. In our case, we use minimally voltage-sensitive blue-elicited fluorescence to measure background. Khwaounjoo et al. (28) estimated background by finding action potential upstrokes, assuming an APD, and replacing corresponding signal windows with linear segments. This approach was effective in their transected, pinned rat LV preparation, but may be more challenging to apply in working heart preparations from large species in which action potentials are longer, motion is greater, and excitation light is less uniform. Seo et al. (11) and Bagwe et al. (27) used dual-emission wavelengths to suppress motion artifacts. In this scheme, a single wavelength is used to excite fluorescence, but two emission wavelengths (with differing voltage sensitivities) are recorded (8). Dual-emission ratiometry requires optics to split the fluorescence image and project it with precise alignment onto either two cameras or two halves of a single camera sensor. Assuming a single mapping camera, the tradeoffs between dual emission and dual excitation ratiometry are: 1) emission ratiometry halves spatial resolution while excitation ratiometry halves temporal resolution (7); and 2) emission ratiometry requires more complex and bulky optics to collect fluorescence while excitation ratiometry requires a more complex setup to deliver excitation light. Favoring spatial resolution and compactness, we chose excitation ratiometry for our design. The compactness makes the system more easily extensible to multiple viewpoints for panoramic imaging of all sides of the heart.

Limitations and future development

In its current form, our method records Vm from an epicardial region that can be imaged with a single camera (e.g., Fig. 4). When strain is recorded as well as Vm, the mapped region must also be imaged by at least two geometry cameras. Because of the curvature of the heart, this somewhat reduces the mapped field. However, the mapped region can be enlarged simply by adding additional cameras and light sources. Mapping the entire epicardium is possible, but would require all points on the surface to be illuminated with excitation light and imaged by at least one mapping camera and two geometry cameras. In principle, the mapping cameras could also be used for geometry, thus economizing on the total number of cameras and simplifying positioning of components. However, this would require mapping cameras with higher spatial resolution than those used in this study to ensure accurate epicardial strain measurements. With any camera positioning design, all cameras would be calibrated with the same calibration target (e.g., Fig. S3) to the same global 3D coordinate system, making it straightforward to blend all data to the same 3D surface model.

Like most optical mapping methods, ours is limited to epicardial Vm data. It is potentially feasible to supplement epicardial data with intramural data recorded with needle electrodes (33) or fiber optic-based optrodes (34), although care would have to be taken to avoid obscuring the epicardial mapped region. Another possible approach would be to supplement epicardial data with simultaneous endocardial recordings from a basket electrode array (35). Similarly, unlike deformation measurement methods based on 3D imaging (17, 30, 31), strains obtained with our method are limited to the epicardium. One potential way to add transmural deformation data would be the use of sonomicrometry crystals (36). Epicardial crystals could potentially serve as markers and therefore minimize obscuring camera views of the epicardium.

Our method currently uses isolated heart preparations perfused with crystalloid solution, but could in principle be adapted to in vivo preparations. Because hemoglobin strongly absorbs light in the wavelengths we employ, this would most likely require the spectral scheme to be redesigned using longer-wavelength potentiometric dyes (37, 38).

In some cases, residual motion artifacts are present in Vm recordings. This is most often manifest as altered baseline (e.g., Fig. 4 C). We believe these artifacts have two sources. First, excitation ratiometry requires the ratio of the intensities of the two excitation wavelengths to be spatially homogeneous across the mapped region (or at least along the trajectory of each mapped tissue site. In other words, at any epicardial site, the ratio Ib(u,t) / Ic(u,t) in Eq. 8 should not be time-dependent). Although we came very close to this ideal by using color mixing optics within individual excitation light units, there were differences across the four light units that likely contributed to motion artifacts. This can be improved with more controlled light-source fabrication processes. Second, we observed that motion artifacts tend to be more pronounced when the angle of the tissue changes with respect to the image plane (Fig. 6). The index of refraction of water as well as tissue is wavelength-dependent (39). Therefore, the ratio of blue to cyan excitation light that is transmitted into the tissue (rather than being reflected from the surface) can change as the surface angle changes. Light transport within the tissue is also anisotropic and wavelength-dependent, which could further contribute to artifacts (39). Those wavelength-dependent properties essentially render the ratio of time-dependent, and thereby cause the residual motion artifacts. Such artifacts are a small percentage of total fluorescence and can be minimized by the future development of voltage reporters that produce larger Vm-related fluorescence change. All motion artifacts can be reduced by restraining the heart to minimize rigid-body motion.

In this implementation, for simplicity, we assume that strain within marker triangles is homogeneous. One way to relax this assumption would be to employ the nonhomogeneous analysis method introduced by Hashima et al. (25). This method fits a finite-element mesh based on bicubic Hermite interpolation to the marker coordinates. Smoothing constraints prevent poorly conditioned fits in regions with low marker density. The result is a smooth, continuous strain field across the marked region. The primary drawback of such a method is added complexity in analysis; however, no additional data would have to be collected.

Our method relies on markers that are manually attached to the epicardium. This is straightforward in large hearts and is manageable, though more difficult, in much smaller rabbit hearts (40). The method can in principle be adapted to rat or mouse hearts; however, this would most likely require new techniques for marker attachment to be developed.

Conclusions

We present a novel, to our knowledge, method for optical mapping of cardiac electromechanics. By recording Vm and epicardial deformation simultaneously, the method eliminates the need for excitation-contraction uncoupling agents and extends optical mapping to beating-heart preparations. We show that the method can map early changes to electromechanical function after coronary artery occlusion (Fig. 8). The method has also been used to investigate the relationship between APD and workload in biventricular working rabbit hearts (40). The method has potential to provide insight in many clinically relevant areas, such as investigating relationships between myocardial stretch and arrhythmogenesis; evaluating the regional contractile response to pacing regimens in cardiac resynchronization therapy; and evaluating the electrical and mechanical integration of tissue engineered constructs or cell therapy for injured myocardium.

Author Contributions

J.M.R. and H.Z. designed research; H.Z., K.I., J.H., G.P.W., and J.M.R. performed research; and H.Z. and J.M.R. analyzed data and wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shannon Salter and Sharon Melnick for their help with animal preparation, and Anastasia Wengrowski, Kara Garrott, and Matthew Kay for helpful comments.

This work was supported by grant No. R01-HL115108 (J.M.R.), National Science Foundation grant No. CBET 0756117 (J.M.R.), and American Heart Association grant No. 10GRNT4280098 (J.M.R.).

Editor: James Sneyd.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods, eight figures, and two movies are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)30447-7.

Appendix A: Reconstruction of Membrane Potential Signals

We seek a simple relationship between recorded fluorescence and Vm. Let u be a barycentric coordinate vector relative to a triangle of three epicardial markers (e.g., l, m, and n in Fig. S5). If the markers are spaced closely enough that deformation within the triangle can be considered homogeneous, then u identifies a material point on the epicardial surface. Fig. 3 indicates that our marker spacing is sufficient for this to be the case. The intensity of fluorescent light emitted from the epicardial point at time t, F(u,t), can be modeled as (41)

| (1) |

where I(u) is the intensity of excitation light incident at that point; A(u) is a parameter describing how efficiently fluorescence is elicited that depends on dye concentration, light-tissue interaction, excitation light wavelength, and emission wavelength of interest; a(u) is a parameter related to voltage sensitivity; Vm(u,t) is membrane potential; and F0(u) is the non-voltage-sensitive background.

Let x be a coordinate vector in the image plane that identifies a camera pixel. If the heart is stationary relative to the camera—the situation during conventional optical mapping using an electromechanical uncoupler—the pixel corresponding to an epicardial site is x(u) and the fluorescence recorded from site u is

| (2) |

where B(u) is a parameter related to the relative positions of the site and camera, and cdark is a constant offset (the intensity value of a pixel when the pixel is not exposed to light). The value cdark is subtracted before further processing and will be neglected in the rest of this development. In conventional optical mapping, recorded fluorescence is therefore linearly related to Vm. Typical practice is to find independent offset and scale factors for each recording site that maps action potentials into a common range (e.g., baseline = 0, fully depolarized = 1) (42).

If the heart is undergoing rigid body motion and/or contracting, the relationship between u and x becomes a function of time (Fig. S5),

| (3) |

where x0(u) is the pixel associated with u in the first camera frame and D(u,t) is the displacement vector from x0 to the pixel associated with u at time t. D(u,t) is derived from marker tracking. Because markers are tracked with subpixel accuracy, x may not have integral values (i.e., not indicate a position in the center of a pixel). In this case, the fluorescence recorded from position x at time t is bilinearly interpolated from the four pixels closest to x. The intensity of incident excitation light I and the parameters A and B also become functions of time. Thus, in a moving heart,

| (4) |

We seek to use to estimate Vm; however, none of the other quantities on the right-hand side of Eq. 4 are known. We therefore employ excitation ratiometry to cancel them. In this scheme, the excitation wavelength is switched with each camera frame. Samples of from adjacent even frames are averaged so that the result is approximately simultaneous with the intervening odd frame. The passband of the emission filter on the mapping camera is very close to the isosbestic point for blue excitation light. Thus, blue-elicited fluorescence is not sensitive to Vm and Eq. 4 becomes

| (5) |

and

| (6) |

for blue and cyan excitation, respectively, where the superscripts indicate excitation color. Note that B(u,t), which is a geometric parameter, is the same for both equations. The parameter a(u) applies only to cyan excitation and is negative because as Vm becomes more positive during depolarization, fluorescence decreases (Fig. 1, B and D). The ratio of blue- and cyan-elicited fluorescence recorded from an epicardial site on adjacent frames is

| (7) |

If both excitation light colors have the same spatial pattern when projected on the heart (even if the mean intensity differs) and both excitation light colors interact with the tissue in the same way, then

| (8) |

is a constant at each site (i.e., not time-dependent). The ratio signal at each site becomes

| (9) |

Fractional fluorescence (the fluorescence change elicited by a full action potential relative to the background fluorescence) is generally <5%. Therefore, a(u)Vm(u,t) is small compared to and Eq. 9 is approximated as

| (10) |

None of the quantities on the right-hand side of Eq. 10, except for Vm(u,t), are functions of time, so the ratio signal and Vm(u,t) are linearly related. Ratio signals from each epicardial site can therefore be scaled to map action potentials into a common range as is typically done in conventional optical mapping. Because a(u) is negative, optical action potentials are upright.

Supporting Citations

References (43, 44, 45) appear in the Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

A Langendorff-perfused pig heart was paced from the LV apex. Vm signals for all pixels that were within the mapped region in the first frame of a mapping run were reconstructed. Depolarization was registered in each signal by detecting the peak of the first derivative and repolarization was registered as 50% repolarization from peak action potential amplitude. Sites in the first and last 10% of the action potential are colored light blue and red, respectively. Sites at intermediate potentials are colored yellow. For each frame, the color-coded action potential image was spatially filtered with a 3 × 3 pixel window and blended with the original camera image.

The left panel is prepared in the same way as Movie S1. In the right panel, red bars indicate positive strains (stretch) and blue bars indicate negative strains (shortening). The bars are oriented in the major/minor directions. Strains are relative to end-diastole.

References

- 1.Efimov I.R., Nikolski V.P., Salama G. Optical imaging of the heart. Circ. Res. 2004;95:21–33. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000130529.18016.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brack K.E., Narang R., Ng G.A. The mechanical uncoupler blebbistatin is associated with significant electrophysiological effects in the isolated rabbit heart. Exp. Physiol. 2013;98:1009–1027. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.069369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee M.H., Lin S.F., Chen P.S. Effects of diacetyl monoxime and cytochalasin D on ventricular fibrillation in swine right ventricles. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001;280:H2689–H2696. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qin H., Kay M.W., Rogers J.M. Effects of heart isolation, voltage-sensitive dye, and electromechanical uncoupling agents on ventricular fibrillation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003;284:H1818–H1826. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00923.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuzmiak-Glancy S., Jaimes R., 3rd, Kay M.W. Oxygen demand of perfused heart preparations: how electromechanical function and inadequate oxygenation affect physiology and optical measurements. Exp. Physiol. 2015;100:603–616. doi: 10.1113/EP085042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wengrowski A.M., Kuzmiak-Glancy S., Kay M.W. NADH changes during hypoxia, ischemia, and increased work differ between isolated heart preparations. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2014;306:H529–H537. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00696.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachtel A.D., Gray R.A., Rogers J.M. A novel approach to dual excitation ratiometric optical mapping of cardiac action potentials with di-4-ANEPPS using pulsed LED excitation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2011;58:2120–2126. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2011.2148719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knisley S.B., Justice R.K., Johnson P.L. Ratiometry of transmembrane voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye emission in hearts. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000;279:H1421–H1433. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.3.H1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohde G.K., Dawant B.M., Lin S.-F. Correction of motion artifact in cardiac optical mapping using image registration. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2005;52:338–341. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2004.840464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourgeois E.B., Bachtel A.D., Rogers J.M. Simultaneous optical mapping of transmembrane potential and wall motion in isolated, perfused whole hearts. J. Biomed. Opt. 2011;16:096020. doi: 10.1117/1.3630115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seo K., Inagaki M., Sugiura S. Structural heterogeneity in the ventricular wall plays a significant role in the initiation of stretch-induced arrhythmias in perfused rabbit right ventricular tissues and whole heart preparations. Circ. Res. 2010;106:176–184. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohl P., Ravens U. Cardiac mechano-electric feedback: past, present, and prospect. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2003;82:3–9. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(03)00022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franz M.R., Cima R., Kurz R. Electrophysiological effects of myocardial stretch and mechanical determinants of stretch-activated arrhythmias. Circulation. 1992;86:968–978. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.3.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trayanova N.A., Constantino J., Gurev V. Models of stretch-activated ventricular arrhythmias. J. Electrocardiol. 2010;43:479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fluhler E., Burnham V.G., Loew L.M. Spectra, membrane binding, and potentiometric responses of new charge shift probes. Biochemistry. 1985;24:5749–5755. doi: 10.1021/bi00342a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montana V., Farkas D.L., Loew L.M. Dual-wavelength ratiometric fluorescence measurements of membrane potential. Biochemistry. 1989;28:4536–4539. doi: 10.1021/bi00437a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meier G.D., Bove A.A., Lynch P.R. Contractile function in canine right ventricle. Am. J. Physiol. 1980;239:H794–H804. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.239.6.H794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heikkilä J. Geometric camera calibration using circular control points. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2000;22:1066–1077. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCulloch A.D., Smaill B.H., Hunter P.J. Left ventricular epicardial deformation in isolated arrested dog heart. Am. J. Physiol. 1987;252:H233–H241. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.252.1.H233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fedorov V.V., Lozinsky I.T., Efimov I.R. Application of blebbistatin as an excitation-contraction uncoupler for electrophysiologic study of rat and rabbit hearts. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:619–626. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Efimov I.R., Huang D.T., Salama G. Optical mapping of repolarization and refractoriness from intact hearts. Circulation. 1994;90:1469–1480. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.3.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boukens B.J., Efimov I.R. A century of optocardiography. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2014;7:115–125. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2013.2286296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waldman L.K., Fung Y.C., Covell J.W. Transmural myocardial deformation in the canine left ventricle. Normal in vivo three-dimensional finite strains. Circ. Res. 1985;57:152–163. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azhari H., Weiss J.L., Shapiro E.P. Noninvasive quantification of principal strains in normal canine hearts using tagged MRI images in 3-D. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:H205–H216. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.1.H205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashima A.R., Young A.A., Waldman L.K. Nonhomogeneous analysis of epicardial strain distributions during acute myocardial ischemia in the dog. J. Biomech. 1993;26:19–35. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(93)90610-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Leuven S.L., Waldman L.K., Covell J.W. Gradients of epicardial strain across the perfusion boundary during acute myocardial ischemia. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;267:H2348–H2362. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.6.H2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bagwe S., Berenfeld O., Jalife J. Altered right atrial excitation and propagation in connexin40 knockout mice. Circulation. 2005;112:2245–2253. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.527325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khwaounjoo P., Rutherford S.L., Smaill B.H. Image-based motion correction for optical mapping of cardiac electrical activity. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2015;43:1235–1246. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez M.P., Nygren A. Motion estimation in cardiac fluorescence imaging with scale-space landmarks and optical flow: a comparative study. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015;62:774–782. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2364959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dandel M., Lehmkuhl H., Hetzer R. Strain and strain rate imaging by echocardiography—basic concepts and clinical applicability. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2009;5:133–148. doi: 10.2174/157340309788166642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prinzen F.W., Hunter W.C., McVeigh E.R. Mapping of regional myocardial strain and work during ventricular pacing: experimental study using magnetic resonance imaging tagging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999;33:1735–1742. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00068-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laughner J.I., Zhang S., Efimov I.R. Mapping cardiac surface mechanics with structured light imaging. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012;303:H712–H720. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00269.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers J.M., Melnick S.B., Huang J. Fiberglass needle electrodes for transmural cardiac mapping. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2002;49:1639–1641. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2002.805483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hooks D.A., LeGrice I.J., Smaill B.H. Intramural multisite recording of transmembrane potential in the heart. Biophys. J. 2001;81:2671–2680. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eldar M., Ohad D.G., Greenspon A.J. Transcutaneous multielectrode basket catheter for endocardial mapping and ablation of ventricular tachycardia in the pig. Circulation. 1997;96:2430–2437. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sasayama S., Franklin D., McKown D. Dynamic changes in left ventricular wall thickness and their use in analyzing cardiac function in the conscious dog. Am. J. Cardiol. 1976;38:870–879. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90800-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matiukas A., Mitrea B.G., Loew L.M. Near-infrared voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes optimized for optical mapping in blood-perfused myocardium. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:1441–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salama G., Choi B.-R., Waggoner A.S. Properties of new, long-wavelength, voltage-sensitive dyes in the heart. J. Membr. Biol. 2005;208:125–140. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0826-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Splinter R., Hooper B.A. Taylor & Francis; New York, NY: 2007. An Introduction to Biomedical Optics. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garrott K., Wengrowski A., Kay M. Basic Cardiovascular Sciences 2015 Scientific Sessions; 2015. Shortening of action potential duration with increased work in contracting rabbit heart (Abstract)http://eventegg.com/bcvs-2015/ [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tai D.C.-S., Caldwell B.J., Smaill B.H. Correction of motion artifact in transmembrane voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye emission in hearts. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004;287:H985–H993. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00574.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kay M.W., Amison P.M., Rogers J.M. Three-dimensional surface reconstruction and panoramic optical mapping of large hearts. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2004;51:1219–1229. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2004.827261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Araki Y., Usui A., Ueda Y. Pressure-volume relationship in isolated working heart with crystalloid perfusate in swine and imaging the valve motion. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2005;28:435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chinchoy E., Soule C.L., Iaizzo P.A. Isolated four-chamber working swine heart model. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2000;70:1607–1614. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01977-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dunn F., Parberry I. Worldware Publishing; Plano, TX: 2002. 3D Math Primer for Graphics and Game Development. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A Langendorff-perfused pig heart was paced from the LV apex. Vm signals for all pixels that were within the mapped region in the first frame of a mapping run were reconstructed. Depolarization was registered in each signal by detecting the peak of the first derivative and repolarization was registered as 50% repolarization from peak action potential amplitude. Sites in the first and last 10% of the action potential are colored light blue and red, respectively. Sites at intermediate potentials are colored yellow. For each frame, the color-coded action potential image was spatially filtered with a 3 × 3 pixel window and blended with the original camera image.

The left panel is prepared in the same way as Movie S1. In the right panel, red bars indicate positive strains (stretch) and blue bars indicate negative strains (shortening). The bars are oriented in the major/minor directions. Strains are relative to end-diastole.