ABSTRACT

Our goal was to develop a robust tagging method that can be used to track bacterial strains in vivo. To address this challenge, we adapted two existing systems: a modular plasmid-based reporter system (pCS26) that has been used for high-throughput gene expression studies in Salmonella and Escherichia coli and Tn7 transposition. We generated kanamycin- and chloramphenicol-resistant versions of pCS26 with bacterial luciferase, green fluorescent protein (GFP), and mCherry reporters under the control of σ70-dependent promoters to provide three different levels of constitutive expression. We improved upon the existing Tn7 system by modifying the delivery vector to accept pCS26 constructs and moving the transposase genes from a nonreplicating helper plasmid into a temperature-sensitive plasmid that can be conditionally maintained. This resulted in a 10- to 30-fold boost in transposase gene expression and transposition efficiencies of 10−8 to 10−10 in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and E. coli APEC O1, whereas the existing Tn7 system yielded no successful transposition events. The new reporter strains displayed reproducible signaling in microwell plate assays, confocal microscopy, and in vivo animal infections. We have combined two flexible and complementary tools that can be used for a multitude of molecular biology applications within the Enterobacteriaceae. This system can accommodate new promoter-reporter combinations as they become available and can help to bridge the gap between modern, high-throughput technologies and classical molecular genetics.

IMPORTANCE This article describes a flexible and efficient system for tagging bacterial strains. Using our modular plasmid system, a researcher can easily change the reporter type or the promoter driving expression and test the parameters of these new constructs in vitro. Selected constructs can then be stably integrated into the chromosomes of desired strains in two simple steps. We demonstrate the use of this system in Salmonella and E. coli, and we predict that it will be widely applicable to other bacterial strains within the Enterobacteriaceae. This technology will allow for improved in vivo analysis of bacterial pathogens.

INTRODUCTION

The ability to generate recombinant strains of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica has facilitated insight into their ecology and pathogenic mechanisms. In recent years, strain collections consisting of single-gene knockouts of the entire genomes of E. coli K-12 (1) and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium 14028 (2) have been assembled. These collections can be used for finely tuned analysis of gene function and host-pathogen interactions, as well as for strain fitness and competition experiments (3). There are also a wide array of reporter systems available to analyze gene expression in detail, for the ordering of hierarchical gene circuits (4), a deeper understanding of metabolism (5), or the development of biosensors (6). The use of these systems, coupled with next-generation sequencing approaches that have facilitated functional genomics (7, 8), allows for unprecedented access to and understanding of the inner workings of the microbial cell.

Despite these recent advances in molecular tools, there is a need for improved in vivo analysis of bacterial pathogens (9). It is necessary to validate the expression of individual genes identified by next-generation sequencing applications, such as transposon insertion sequencing (Tn-seq) (10), or to complement in vivo-specific genetic techniques, such as in vivo expression technology (IVET) (11). Chromosomal integration is desirable because it provides improved stability and more stoichiometric expression than plasmid-based expression. Since the original publication of the mini-Tn7 transposition method in 2005 (12), it has proven to be an incredibly useful system for integrating genes into bacterial chromosomes, particularly with Pseudomonas species (13). Tn7 transposition is ideal because it is directional (14), is highly specific for attTn7 sites (15), and results in single-copy insertion in most bacterial species (13). For Salmonella and E. coli, the single attTn7 site lies near the conserved glmS gene (16). Modifications have been made in an attempt to improve the flexibility of the Tn7 system, such as through the generation of new helper plasmids (17), helper plasmid and delivery plasmid hybrids (18), arabinose-inducible gene expression (19), and luciferase integration (20, 21). Unfortunately, the Tn7 system (12, 18) did not work in our hands for Salmonella. We speculated that this was due to low expression of the tnsABCD genes, which are necessary for transposition to occur.

In this article, we describe a modified mini-Tn7 system that is amenable for use in the Enterobacteriaceae and provides the means necessary to combine modern, high-throughput technologies with classical molecular genetics. We built a replication-proficient Tn7 helper plasmid based on a temperature-sensitive replicon and demonstrate that tnsABCD expression is boosted 10 to 30 times compared to that with the original helper plasmids (12). Furthermore, we incorporated the pCS26 vector system, which was designed to be modular and has a long history of use in gene expression experiments (4, 22–24). This gives exceptional control over promoter and reporter combinations, which can be tested in vitro and are only two steps away from chromosomal integration. We generated reporter strains of S. Typhimurium and E. coli with luminescent and fluorescent reporters and kanamycin or chloramphenicol antibiotic selection, and we describe synthetic σ70-dependent promoters that provide constitutive expression at three different levels. Further, we showcase the effectiveness of gene complementation using this system, an important requirement for the robust validation of gene function discovery. This system is amenable for use in the Enterobacteriaceae and provides the means necessary to combine classical molecular genetics with modern, high-throughput technologies in both in vitro and in vivo settings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain ATCC 14028 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) and E. coli APEC O1 (25) were used as the parental strains in this study. The isogenic S. Typhimurium ΔcsgD strain, formerly named S. Typhimurium ΔagfD, has been described previously (26). All cloning experiments were performed in E. coli DH10B(pCS26, pHSG415, pACYC184) or E. coli CC118(λpir) (27) (pUC18R6K-mini-Tn7T). All oligonucleotides used are listed in Table 1. Prior to plasmid purification, cloning, and analysis, strains were inoculated from frozen stocks onto LB agar (lysogeny broth-Miller plus 1.5% agar) supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics (kanamycin [Kn], 50 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol [Cm], 10 μg ml−1) and grown for 20 h at 37°C. One isolated colony was used to inoculate 5-ml LB cultures.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| pCS26-Eco | GCCGAATTCCGGCAAGAAAGCCATCCAGTTTACTT | To generate Cmr-pCS26 |

| pCS26-Pst | GCCCTGCAGGCGGGACTCTGGGGTTCGAGAGCTCGCTTGGACTCC | To generate Cmr-pCS26 |

| Bam_out_Pst | GCCCTGCAGGTCGACTCTAGACGATCCCC | To generate Cmr-pCS26 |

| Pst_to_terminator | CGGGACTCTGCAGTTCGAGAGCTCGCTTGGACTCCTG | To generate Cmr-pCS26 |

| sig70-16_sense | TCGAGAATAATTCTTTACATTTATGCTTCCGGCTCGTATTCTACGTGCAATTG | sig70_16 promoter |

| sig70-16_antisense | GATCCAATTGCACGTAGAATACGAGCCGGAAGCATAAATGTAAAGAATTATTC | |

| sig70_16-10c2F | TCGAGAATAATTCTTTACATTTATGCTTCCGGCTCGTATAATACGTGCAATTG | sig70c10 promoter |

| sig70_16-10c2R | GATCCAATTGCACGTATTATACGAGCCGGAAGCATAAATGTAAAGAATTATTC | |

| sig70_16-35c2F | TCGAGAATAATTCTTGACATTTATGCTTCCGGCTCGTATTCTACGTGCAATTG | sig70c35 promoter |

| sig70_16-35c2R | GATCCAATTGCACGTAGAATACGAGCCGGAAGCATAAATGTCAAGAATTATTC | |

| pZE05rev | TCACCGACAAACAACAGATA | To amplify mCherry |

| TNS2forEco | GATCGAATTCATGCTGTGAAAAAGCATACTGGACT | To amplify tnsABCD from pTNS2 |

| TNS2revXma | GATCCCCGGGATTTTGGCTCGTTGAAGATCCGATG | |

| Sac_Pac_Kpn1 | CTTAATTAAGGTAC | PacI polylinker inserted in pUC18R6K-mini-Tn7T |

| Sac_Pac_Kpn2 | CTTAATTAAGAGCT | |

| mCherry-check | TGCGTGGTACTAATTTTCCA | To verify chromosomal insertion of mCherry |

| GFP-check | TACATCATGGCAGACAAACA | To verify chromosomal insertion of GFP |

| Lux-check | TCAACACTTGTTTCTTTGAGG | To verify chromosomal insertion of luxCDABE |

| glmSdetectFor | AACCACCCGTTCAGGCTGGCTA | To verify chromosomal insertion at glmS site |

| glmSdetectRev | ACGTTGACCAGCCGCGTAAC | |

| Cm-check | CCCCGTGGAGGTAATAATTG | To verify chromosomal insertion of Cmr marker |

| Kn-check | TACCCGTGATATTGCTGAAG | To verify chromosomal insertion of Knr marker |

| csgDcompFor2 | GATTCTCGGGCATCATAAATAACAATTTGT | To generate csgD-cat construct |

| csgDcompREV | GTTCGAATTCCCTTACCGCCTGAGATTATC | |

| csgDFOR_Bam | GGCCGGATCCCATCATAAATAACAATTTGT | |

| glmScsgDREV_Pst | GGCCCTGCAGGGCCGTCGATAGACGGCCTTTTTTTGTGCGCCGTGACAGGCGCTGTTCTTCCTTACCGCCTGAGATTATC | |

| glmSCAMfor_Eco | GGCCGAATTCAGCGCAGGTAGGCGTAGCACCTCTTAGTCGCTCTTCAGCCACCATAGAGAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | |

| CAMrev_Bam | GGCCGGATCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTA | |

| CAMfor_Eco | GGCCGAATTCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | |

| csgDREV_Kpn | GGCCGGTACCCCTTACCGCCTGAGATTATC | |

| tnsA-for | ATACGAGCCTTAACCGCAAA | qRT-PCR for tnsA |

| tnsA-rev | CGCAACTCCTCCATATTCAC | |

| tnsB-for | TGCCACGATTGCTGATATTT | qRT-PCR for tnsB |

| tnsB-rev | GCCACCACATAAGACGGATT | |

| tnsC-for | CGCATTGCTCGTTATTCTGA | qRT-PCR for tnsC |

| tnsC-rev | TGACGCTGATCTTCGGTATC | |

| tnsD-for | AATGCTAGGAGTCGCTGCTT | qRT-PCR for tnsD |

| tnsD-rev | TACCAATCTCGTTGCCAAAA | |

| fabG1 | CAGCGTGCGGGTATCCTGGC | qRT-PCR control gene |

| fabG2 | CCGCCGTTGACGTGCAGAGT | |

| groEL1 | CGTTGCGCTGATCCGCGTTG | qRT-PCR control gene |

| groEL2 | GACGGCTCTTCGCCGCAGTT |

Nucleotide sequences corresponding to restriction enzyme sites are underlined.

For bioluminescence assays, overnight cultures of S. Typhimurium or E. coli strains carrying pCS26 derivatives (luxCDABE, green fluorescent protein [GFP], or mCherry reporters) were diluted 1 in 600 in 1% tryptone broth or LB supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 Kn or 10 μg ml−1 Cm to a final volume of 150 μl in 96-well clear-bottom black plates (9520 Costar; Corning Inc.). pCS26 bacterial luciferase (lux) operon fusion plasmids containing csgDEFG, csgBAC, and adrA promoters have been described previously (26). The RpoS-dependent reporter plasmid sig38H4 contains a promoter that was designed based on alignment of numerous RpoS-controlled promoters, driving expression of the lux operon (26, 28). For E. coli or S. Typhimurium strains with reporters integrated into the genome, final dilution was performed into media without antibiotics. The cultures in each well were overlaid with 50 μl of mineral oil prior to starting the assays, to minimize evaporation of the culture medium. Cultures were assayed for absorbance (590 to 600 nm, 0.1 s), luminescence (1 s; in counts per second [cps]), or fluorescence (GFP, excitation at 485 nm and emission at 535 nm; mCherry, excitation at 555 ± 38 nm and emission 632 ± 45 nm) every 30 min during growth at 37°C with agitation in a Victor X3 multilabel plate reader (Perkin-Elmer).

Strains used in murine infection experiments were inoculated from frozen stocks onto LB agar supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 Kn or 10 μg ml−1 Cm. Isolated colonies were selected and grown for 16 h in LB broth at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. These cultures were used to generate the bacterial challenge solutions used to infect mice.

Generation of a Cmr pCS26 plasmid.

The Kn-resistant (Knr) reporter plasmid pCS26 containing the promoterless luxCDABE operon from Photorhabdus luminescens has been previously described (22). The lux gene products from P. luminescens are more thermostable than those from Vibrio species and thus are more suitable for gene expression experiments (29, 30). To generate a chloramphenicol-resistant (Cmr) version of pCS26, inverse PCR was performed using primers pCS26-Eco and pCS26-Pst to remove the aph gene, coding for Knr. The linear PCR product was digested with EcoRI and PstI (New England BioLabs [NEB]). The cat gene, coding for Cmr, was part of a 1.1-kb blunt-ended insert from a PCR Script AMP cloning kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), which was cloned into SmaI-digested pUC18 and excised by digestion with EcoRI and PstI. The inverse PCR product and the Cmr fragment were ligated using T4 DNA ligase (New England BioLabs). To remove a second BamHI site that was introduced as part of the Cmr fragment, inverse PCR was performed using primers Bam_out_Pst and Pst_to_terminator. The product of inverse PCR was digested with PstI and ligated using T4 DNA ligase to generate the final pCS26-Cm vector.

Generation of sig70_16, sig70c10, and sig70c35 promoter constructs.

sig70_16 is a derivative of pCS26 that contains a synthetic, σ70-dependent promoter controlling luxCDABE expression (31). To generate a sig70_16 version of pCS26-Cmr, oligonucleotides sig70-16_sense and sig70-16_antisense were phosphorylated using T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB) at 37°C for 1 h in buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 8), 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM ATP, and 1.5 μg of bovine serum albumin (BSA). The phosphorylated oligonucleotides were mixed, heated at 80°C for 7 min, and allowed to cool slowly to 30°C, and the annealed product was ligated into XhoI/BamHI-digested pCS26-Cmr. To generate sig70c10 and sig70c35 promoter variants, oligonucleotides sig70_16-10c2F and sig70_16-10c2R and oligonucleotides sig70_16-35c2F and sig70_16-35c2R were phosphorylated and annealed as described above and then ligated into XhoI/BamHI-digested pCS26-Knr or -Cmr vectors. Clones were screened for light production using an IVIS Lumina II in vivo imaging system (PerkinElmer). DNA sequencing (Eurofins MWG Operon) was performed on all constructs using primers pZE05 and pZE06 (22).

Generation of GFP and mCherry pCS26 reporter plasmids.

pCS26-Knr and -Cmr containing sig70_16, sig70c10 and sig70c35 promoters were digested with NotI, and the 7,300-bp luxCDABE-containing fragment was removed. GFP-containing fragments were PCR amplified from pCS21 (22) and mCherry-containing fragments were PCR amplified from PadrA-mCherry (32), using primers pZE05 (22) and pZE05rev. Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used, and reaction conditions were as outlined by the manufacturer. The resulting products were digested with NotI, ligated into the pCS26 vectors, and transformed into E. coli DH10B. Potential clones were selected on LB agar supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics and screened for fluorophore production on the IVIS Lumina II imaging system, as described above. Proper orientation of reporter constructs was confirmed by plasmid purification followed by restriction digestion.

Modification of the Tn7 delivery and helper plasmids.

The tnsABCD operon was PCR amplified from pTNS2 (12) with Phusion DNA polymerase using primers TNS2forEco and TNS2revXma. The tnsABCD PCR product was digested with EcoRI and XmaI and ligated into EcoRI/XmaI-digested pHSG415 (33). By cloning into this region of pHSG415, tnsABCD expression would be partly controlled by the existing cat promoter. To facilitate cloning of pCS26-based vector fragments into the pUC18R6K-mini-Tn7T plasmid (12), a polylinker containing a PacI restriction site was inserted. Oligonucleotides Sac_Pac_Kpn1 and Sac_Pac_Kpn2 were phosphorylated and annealed as described above and ligated into SacI/KpnI-digested pUC18R6K-mini-Tn7T. The pUC18R6K-mini-Tn7T-PacI vector was used for all subsequent experiments.

Integration into the E. coli and S. Typhimurium chromosomes.

pCS26-Knr and -Cmr constructs were digested with PacI to remove the pSC101-based origin of replication and ligated into PacI-digested pUC16R6K-mini-Tn7T PacI vector. Potential clones in E. coli CC118(λpir) were selected by growth on LB agar supplemented with 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin (Ap) and 10 μg ml−1 Cm or 50 μg ml−1 Kn. To confirm that constructs were ligated in the desired orientation, plasmid purifications were performed, followed by restriction digestion. The resulting mini-Tn7T-pCS26 plasmids, 18 in total, were purified using plasmid midikits (Qiagen). DNA sequencing was performed with primers pZE05 and pZE06 (Lux), pZE05 and mCherry-check (mCherry), or pZE05 and GFP-check (GFP) (Table 1).

Chromosomal integration was achieved by electroporation of 100 ng of the appropriate pUC18R6K-mini-Tn7T-pCS26 vector into competent cells of S. Typhimurium 14028 ΔcsgD or E. coli APEC O1 containing pHSG415-tnsABCD. Competent cells were prepared by growing for 3 to 4 h at 28°C with agitation in LB supplemented with 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin (to maintain the helper plasmid); cells were sedimented by centrifugation (8,000 × g, 10 min) and washed three times in 10% glycerol. After electroporation, cells were allowed to recover in SOC medium for 2 h at 30°C prior to plating on LB agar supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 Kn or 10 μg ml−1 Cm. The final plates were incubated overnight at 37°C to ensure loss of the temperature-sensitive pHSG415-tnsABCD plasmid. To test the existing Tn7 method, 100 ng of pTNS2 (12) or pTNS3 (34) was coelectroporated with 100 ng of mini-Tn7T-pCS26 plasmid into S. Typhimurium or E. coli competent cells. These plasmids do not replicate in Salmonella and E. coli; Tn7 transposition was unsuccessful in these experiments.

Chromosomal integration of reporter fragments into the attTn7 site downstream of the glmS gene of S. Typhimurium or E. coli was confirmed by PCR using the following primer sets: reaction 1, glmSdetectFor plus Lux-check, mCherry-check, or GFP-check; reaction 2, glmSdetectRev plus Cm-check or Kn-check (Table 1). PCR products were purified using QIAquick PCR purification kits (Qiagen), and DNA sequencing was performed (Eurofins MWG Operon). To ensure the absence of secondary mutations in Salmonella reporter strains that were used for murine infection experiments, the reporter fragments (∼3,800 to 8,800 bp) were moved from S. Typhimurium ΔcsgD into the S. Typhimurium 14028 wild-type (WT) strain by P22 phage transduction (35). These P22 phage lysates are also available upon request.

Determination of tnsABCD transcript levels.

RNA was isolated using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) from S. Typhimurium 14028 ΔcsgD cells transformed with pHSG415-tnsABCD, pTNS2, or pTNS3 and allowed to recover for 1 h or 2 h at 30°C in SOC medium (as described in previous section). The quantity and purity of RNA were verified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and integrity was verified on a Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with a Prokaryote Total RNA Nano chip NanoDrop ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A total of 2 μg RNA was then reverse transcribed using the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time PCRs specific for tnsA, tnsB, tnsC, or tnsD (primers are listed in Table 1) were performed on 20 ng equivalent cDNA using Kapa SYBR Fast quantitative PCR (qPCR) master mix (D-Mark Biosciences) on a Step-One-Plus real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Analysis was conducted using the 2−ΔΔCT method (36) with normalization against the geometric mean values for two housekeeping genes, fabG and groEL.

Murine infections with S. Typhimurium reporter strains.

Female C57BL/6 mice (6 to 8 weeks old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed in the VIDO animal facilities in direct accordance with guidelines drafted by the University of Saskatchewan's Animal Care Committee and the Canadian Council on the Use of Laboratory Animals. For competitive index (CI) experiments, two groups of six mice were assigned to groups using a randomization table prepared in Microsoft Excel; individual mice were marked with ear notches. Mice were infected by oral gavage with a mixed inoculum containing a 1:1 ratio of Knr and Cmr S. Typhimurium 14028 strains containing the sig70_16-luxCDABE construct. An inoculum of 1.1 × 107 CFU, containing 5.3 × 106 Knr cells and 5.7 × 106 Cmr cells, was delivered to each mouse in 100 μl of 100 mM HEPES, pH 8. Infected mice were weighed daily, and mice that had a >20% drop in weight, typically at 4 to 7 days postinfection, were humanely euthanized. Spleen, liver, mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), and cecum were collected from each mouse, placed in a 2 ml Eppendorf Safe-Lock tube containing 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and a 5-mm steel bead (Qiagen product 69989), and homogenized using a MM400 high-speed mixer mill (Retsch). For determination of total Salmonella CFU, organ homogenates were serially diluted in PBS and plated on LB agar supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 Kn or 10 μg ml−1 Cm. The CI values were calculated as (CFU Knr/CFU Cmr)output/(CFU Knr/CFU Cmr)input.

For whole-animal imaging experiments performed to compare light production between different reporter strains, groups (n = 4) of C57BL/6 mice were pretreated with an oral dose of 20 mg streptomycin at 24 h prior to challenge (37) with 1 × 107 CFU of individual reporter strains Cmr sig70_16-, sig70c10-, and sig70c35-luxCDABE or Knr-sig70c35-luxCDABE. Postinfection monitoring was performed as described above. Mice were imaged daily using the IVIS Lumina II (PerkinElmer), and final tissue images were obtained after euthanization.

Complementation of S. Typhimurium 14028 ΔcsgD mutant.

For plasmid-based complementation, the region of DNA including the csgD open reading frame (ORF) and intergenic region between the divergently transcribed csgBAC and csgDEFG operons was PCR amplified from S. Typhimurium 14028 genomic DNA using primers csgDcompFor2 and csgDcompREV. The resulting PCR product was purified, digested with EcoRI and AvaI, and ligated into EcoRI/AvaI-digested pACYC184 (38) to generate pACYC-csgD. Product 1, consisting of csgD and the corresponding intergenic region, was PCR amplified from pACYC-csgD using primers csgDFOR_Bam and glmScsgDREV_Pst. Product 2, containing the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene and flanking Flp recombinase target (FRT) sites, was PCR amplified from pKD3 (39) using primers glmSCAMfor_Eco and CAMrev_Bam. Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for all PCRs. EcoRI/BamHI-digested product 2 and BamHI/PstI-digested product 1 were sequentially ligated into EcoRI-BamHI-PstI-digested pTZ18U (Sigma-Aldrich). The cat-csgD product was PCR amplified from pTZ18U using primers CAMfor_Eco and csgDREV_Kpn, digested with EcoRI and KpnI, and ligated into EcoRI/KpnI-digested pUC18R6K-mini-Tn7T. The resulting vector was electroporated into S. Typhimurium ΔcsgD cells containing the pHSG415-tnsABCD helper plasmid. Chromosomal insertion strains were selected by growth on LB agar supplemented with 10 μg ml−1 Cm; final confirmation was performed by PCR using primers glmSdetectFor and glmSdetectRev followed by DNA sequencing.

Statistical analysis.

Maximum luciferase, mCherry, or GFP expression values from E. coli or S. Typhimurium strains harboring pCS26 plasmids or from E. coli APEC O1 or S. Typhimurium 14028 reporter strains were compared between the Knr or Cmr or the sig70_16, sig70c10, or sig70c35 groups using unpaired t tests with Welch's correction, which does not assume that groups have equal standard deviations. Competitive index values calculated from the organs of all 12 mice were first analyzed using a Shapiro-Wilk normality test, which determined that the data were not normally distributed. Wilcoxon signed rank tests determined that the CI values for each organ were not statistically different (P > 0.05) from a theoretical value of 1.0. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v6.0.

RESULTS

Modular pCS26 vectors with synthetic, σ70-dependent promoters.

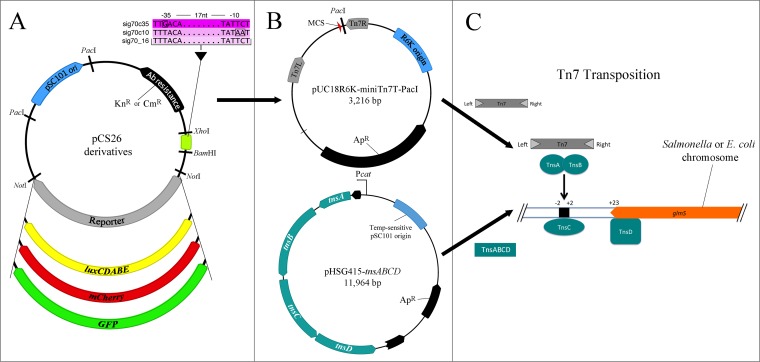

The pCS26 vector, originally developed in one of our laboratories (22; http://www.surettelab.ca/lab/), has been used for several large-scale gene expression experiments (4, 22–24). pCS26 offers flexibility in both the promoters and reporters that can be incorporated (Fig. 1A). We generated versions of pCS26 containing either mCherry or GFP reporters, in addition to the base plasmid containing the luxCDABE operon from Photorhabdus luminescens. To increase the utility of the pCS26 reporter system and enable experiments where strains can be combined, such as competitive infections or fitness assays, we generated a version of pCS26 with chloramphenicol resistance as a selectable marker (see Materials and Methods). We incorporated promoters of increasing strength based on a constitutive, σ70-dependent promoter named sig70_16 (40). This promoter was designed based on the consensus sequence of different σ70-controlled promoters in E. coli, with degenerate positions in the −10 and −35 regions to introduce variability in promoter strength (K. Pabbaraju and M. G. Surette, unpublished data). We reasoned that restoring the sig70_16 sequence back to the consensus −10 or −35 sequence would boost the promoter strength. We named these new promoters sig70c10, with the −10 sequence restored to consensus, and sig70c35, with the −35 sequence restored to consensus (Fig. 1A). Luciferase expression from these plasmids was monitored in E. coli DH10B and S. Typhimurium 14028 during a 48-hour growth period (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In general, the profiles differentiated into three distinct groups, with the sig70_16 promoter having the lowest expression, sig70c10 having intermediate levels, and sig70c35 having the highest expression. There was very little difference in expression between the Knr and Cmr plasmids, except in Salmonella, where the Cmr sig70c35 plasmid construct had a lower maximum expression level (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

Use of modular pCS26 plasmids in a modified Tn7 transposition system. (A) The antibiotic resistance marker (Knr or Cmr), sig70 promoter (or new promoter cloned with XhoI/BamHI), and luxCDABE, mCherry, or GFP (or new reporter cloned with NotI/NotI) in the modular pCS26 plasmid are chosen. The synthetic, σ70-dependent promoters (shown in magenta) allow for constitutive expression at differing strengths; the nucleotide differences are outlined, and −35 and −10 regions are recognized by σ70. (B) pCS26 constructs are digested with PacI and ligated into the pUC18R6K-mini-Tn7T-PacI delivery plasmid. pHSG415-tnsABCD is a new helper plasmid that is replication proficient and can be conditionally maintained in most Enterobacteriaceae strains. The tnsABCD operon is expressed under the control of the preexisting cat promoter, leading to elevated expression; two black arrows represent truncated aph (Knr) and cat (Cmr) genes. (C) One hundred nanograms of mini-Tn7T-pCS26 delivery plasmid is transformed into cells containing pHSG415-tnsABCD, resulting in orientation-specific integration of Knr- or Cmr-promoter-reporter constructs into the attTn7 site (shown as a black box) present in the chromosome of Salmonella or E. coli, downstream of the glmS gene. The details of Tn7 transposition were adapted from reference 16. Chromosomal insertion can be verified by PCR, followed by growth at 37°C to cure the pHSG415 helper plasmid. All plasmid maps were generated using Geneious v. 9.0.4 (Biomatters Inc., Newark, NJ).

Modifying the Tn7 transposition system for chromosomal integration of luxCDABE constructs.

Plasmid stability is a significant issue when it comes to in vivo studies of microbial pathogenesis within a host. To expand the spectrum of uses for the modular pCS26 reporter system, we wanted to develop a chromosomal integration strategy based on Tn7 transposition. The original Tn7 system, first described by Choi et al. (12), consists of two replication-sensitive vectors that are used to carry (i) the gene(s) of interest and (ii) the transposase machinery required for chromosomal integration. The first modification we made to the existing Tn7 system was to insert a PacI polylinker into the multiple-cloning site of the pUC18R6K-mini-Tn7T delivery plasmid (Fig. 1B). This enabled cloning of the promoter, reporter, and antibiotic resistance cassettes from pCS26-Knr or -Cmr. We attempted to integrate the pCS26-luxCDABE constructs into the chromosome of Salmonella using one of the original helper plasmids, pTNS2 (12) or pTNS3 (34), but the experiments were unsuccessful (Table 2). Since pTNS2 and pTNS3 do not replicate in Salmonella, we reasoned that tnsABCD expression might not reach high levels during the transformation process. Therefore, the second modification we made was to generate pHSG415-tnsABCD, a replication-proficient helper plasmid that contains a temperature-sensitive origin of replication to allow for curing of cells. Use of this plasmid, with tnsABCD genes cloned under partial control of the chloramphenicol promoter (Fig. 1B), resulted in 10- to 30-fold-enhanced gene expression as measured by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) (Table 2). We achieved Tn7 transposition of the sig70-luxCDABE reporter constructs into the genome of S. Typhimurium 14028 (Fig. 1C) at high efficiency (Table 2). Since ligation of PacI-digested pCS26 reporter constructs into the mini-Tn7T delivery vector resulted in two possible insert orientations, we used the orientation that had slightly stronger expression (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). For E. coli APEC O1, transposition with pHSG415-tnsABCD was even more efficient than in Salmonella, ranging from 2.2 × 10−8 to 1.4 × 10−10. In contrast, the use of pTNS2 or pTNS3 did not result in any successful transposition events.

TABLE 2.

tnsABCD expression from different Tn7 helper plasmids and resulting transposition frequencies in S. Typhimurium 14028

| Helper plasmida |

tnsABCD expression atb: |

Transposition frequencyc |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h | 2 h | luxCDABE | mCherry | GFP | |

| pTNS2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | <10−10 | <10−10 | <10−10 |

| pTNS3 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 4.2 ± 1.2 | <10−10 | <10−10 | <10−10 |

| pHSG415-tnsABCD | 31.9 ± 3.8 | 33.5 ± 3.6 | 6.0 × 10−9 to 3.8 × 10−10 | 5.6 × 10−9 to 3.8 × 10−10 | 6.0 × 10−9 to 7.5 × 10−10 |

One hundred nanograms of pTNS2 or pTNS3 was electroporated into S. Typhimurium 14028 competent cells. For pHSG415-tnsABCD, competent cells containing this helper plasmid were prepared.

Total RNA was isolated from each competent cell/helper plasmid combination after recovery in SOC medium at 30°C for 1 h or 2 h. Expression levels were calculated individually for tnsA, -B, -C, and -D as described in Materials and Methods; values represent the average fold change and standard deviation for all four genes measured from four biological replicate samples.

For each reporter type, 100 ng of pUC18R6K-mini-Tn7T-pCS26 delivery plasmid, containing one of six different constructs (Knr or Cmr with the sig70_16, sig70c10, or sig70c35 promoter), was electroporated into S. Typhimurium 14028 cells containing the different helper plasmids. The values represent the range of transposition frequencies calculated based on the number of luminescent or fluorescent Knr or Cmr colonies obtained from a total number of 2.7 × 109 competent cells. No colonies were obtained using the pTNS2 or pTNS3 helper plasmid; therefore, the transposition efficiency is listed as less than 10−10.

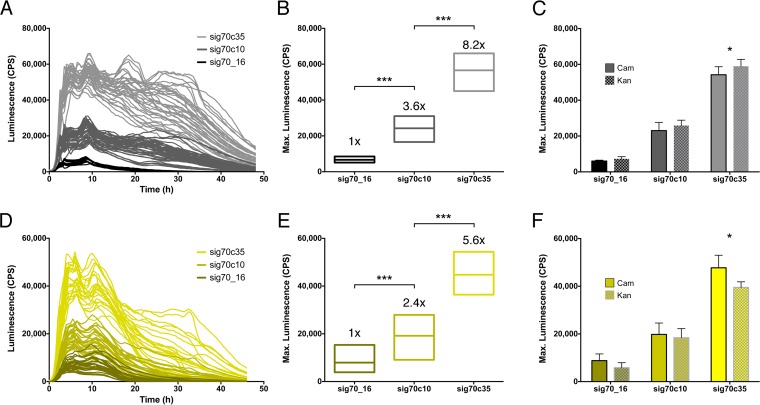

We analyzed the S. Typhimurium 14028 and E. coli APEC O1 luxCDABE reporter strains during growth in liquid culture at 37°C. Expression profiles clustered into three distinct groups based on promoter strength (Fig. 2A and D). For S. Typhimurium 14028, the peak expression values were 8,000 cps for sig70_16, 30,000 cps for sig70c10, and 62,000 cps for sig70c35, which represented stepwise increases of 3.6× and 8.2× (Fig. 2B). For E. coli APEC O1, the increase between sig70_16 and sig70c10 was 2.4× and that between sig70c10 and sig70c35 was 5.6× (Fig. 2E). For both S. Typhimurium and E. coli, there were only small expression differences between the Knr and Cmr constructs (Fig. 2C and F). These results confirmed that the modularity of the pCS26 vector system was conserved upon integration into the chromosome.

FIG 2.

Chromosome-based expression of luciferase in S. Typhimurium and E. coli. Synthetic, σ70-dependent promoter-luxCDABE operon fusions were integrated into the chromosome of S. Typhimurium 14028 ΔcsgD or E. coli APEC O1 using the modified Tn7 transposition system. (A and D) Luciferase expression from each strain was measured during growth at 37°C for 48 h; each line represents the expression curve from one individual reporter strain. (B and E) Box plots show the mean and range of maximum expression values for the different chromosomal reporter strains. Numerical values above the boxes represent the stepwise increase in mean expression levels between promoters. Statistical significance was calculated using unpaired t tests with Welch's correction (***, P < 0.001). (C and F) Maximum expression values for Cmr and Knr strains within each sig70 promoter group are shown, with histogram bars representing the mean and error bars representing the standard deviation. Statistical significance (*) was determined using multiple t tests, corrected for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method (alpha = 5%).

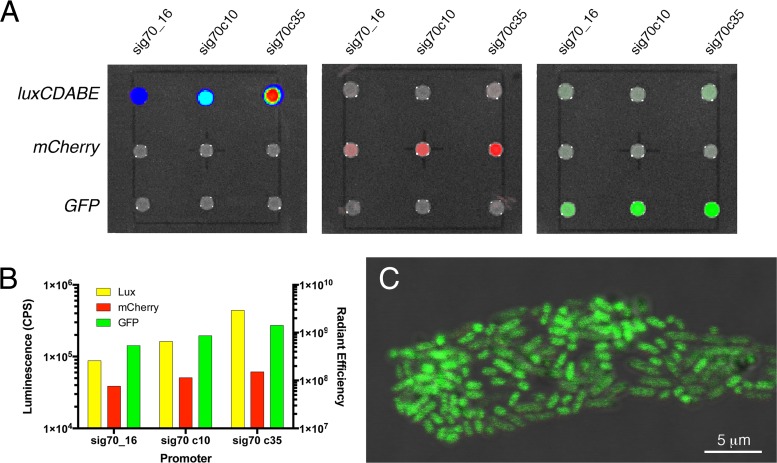

Generating fluorescent S. Typhimurium and E. coli reporter strains.

Fluorescent reporters can be used to visualize bacterial cells by microscopy after tissue sectioning or in in vitro experiments. To this end, we generated mCherry- and GFP-expressing S. Typhimurium reporter strains at high efficiency (Table 2). Expression from these strains was measured after 24 h growth at 37°C on LB agar (Fig. 3A). Increasing levels of expression with the sig70_16, sig70c10 and sig70c35 promoters could be measured for each reporter (Fig. 3B). The dynamic range of GFP and mCherry was reduced compared to that of luciferase; however, a more observable difference between promoters was measured during growth in liquid culture (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Importantly, only minor background fluorescence for GFP-expressing strains was detected in the mCherry channel and vice versa (Fig. 3A). A confocal microscopy image was generated for the Knr S. Typhimurium sig70_16-GFP reporter strain, which demonstrated that individual cells within the population were expressing similar levels of GFP (Fig. 3C). Similar images were generated for the S. Typhimurium mCherry reporter strains (data not shown).

FIG 3.

Fluorescent reporter strains of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028. (A) S. Typhimurium reporter strains with a sig70_16, sig70c10, or sig70c35 promoter controlling luxCDABE, mCherry, or GFP expression were grown on LB agar at 37°C. Expression from the different strains was visualized using an IVIS Lumina II whole-animal imaging system (Perkin-Elmer). (B) Peak luciferase (cps) or fluorescence (radiant efficiency) was measured using the region-of-interest (ROI) module in Living Image software ver. 4.2 (PerkinElmer). (C) Cells of the Knr sig70_16 GFP reporter strain were visualized on a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope, using the 63× oil immersion objective with the 180 laser operating at 488 nm. The scale bar is displayed in the bottom right corner.

mCherry and GFP reporter strains were also generated for E. coli APEC O1 at efficiencies as high as 2.2 × 10−8 (data not shown). As in S. Typhimurium, the expression profiles of the σ70-dependent promoters were distributed into three distinct groups during growth in liquid culture (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Fluorescent APEC O1 cells were also visualized by confocal microscopy (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

Use of luciferase-expressing S. Typhimurium reporter strains in vivo.

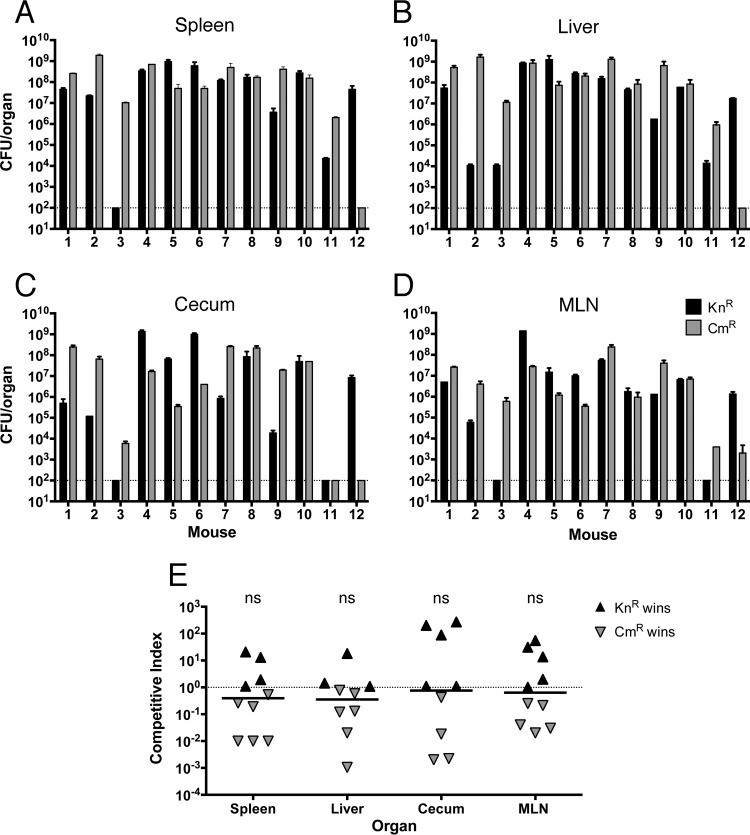

S. Typhimurium is a well-established pathogen capable of causing disease in susceptible mouse strains (41). We wanted to assess the virulence of the bacterial luciferase reporter strains and determine if the antibiotic resistance markers would have any influence. To ensure that Knr and Cmr strains would be recovered with equal efficiencies, we tested their plating efficiencies on LB agar supplemented with 7, 10, or 15 μg ml−1 of Cm or 50 or 100 μg ml−1 of Kn. Similar CFU values were detected for the strains on all media used, indicating that the antibiotic concentration did not affect their recovery (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). C57BL/6 mice were challenged with a 1:1 ratio of Knr and Cmr sig70_16-luxCDABE reporter strains. At 4 to 7 days postinfection, infected mice were euthanized and the bacterial loads in the spleen, liver, cecum, and mesenteric lymph nodes were determined (Fig. 4). In some individual mice, the Knr reporter strain (black bars) was recovered at higher levels, while in other mice, the Cmr reporter strain (gray bars) was recovered at higher levels. Typically, the same strain was recovered at higher levels in all organs from a single mouse, suggesting that the outcome of the competition between the strains was decided early during infection. The competitive index (CI) values were calculated from each individual mouse; for each organ, the values were not significantly different from 1 (Fig. 4E). Based on this experiment, we concluded that the Knr and Cmr S. Typhimurium reporter strains were equally virulent in this model.

FIG 4.

Bacterial counts and competitive indices from C57BL/6 mice after oral infection with S. Typhimurium sig70_16 lux operon fusion strains. (A to D) The spleen (A), liver (B), cecum (C), and MLN (D) were collected from euthanized mice, homogenized, and plated on LB agar supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 Kn or 10 μg ml−1 Cm to determine the levels of each strain present (measured as CFU per whole organ). (E) Competitive index (CI) values were calculated for each mouse in each organ: CI = (CFU Knr OUT/CFU Cmr OUT)/(CFU Knr IN/CFU Cmr IN). A CI value of 1.0, which indicates equal virulence, is represented by a horizontal dotted line. Statistical significance from a value of 1 was determined using a Wilcoxon signed rank test (ns, not significant [P > 0.05]).

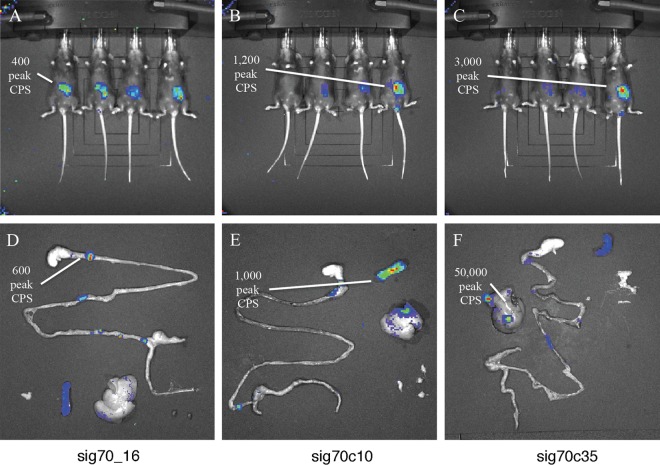

In a separate trial, C57BL/6 mice were orally infected with individual S. Typhimurium sig70_16, sig70c10, and sig70c35 luciferase reporter strains and visualized using a whole-animal imager. Each reporter strain produced a luciferase signal that was detectable within whole mice at day 1 postinfection and in their internal organs at 3 to 6 days postinfection (Fig. 5). Similar to the in vitro experiments, there were stepwise increases in expression between the three promoters, and the sig70c35 reporter strain had the highest levels of light production (Fig. 5C and F). Luciferase production was also detected from S. Typhimurium cells shed into the fecal pellets (data not shown).

FIG 5.

S. Typhimurium reporter strains have various levels of luciferase expression in vivo. C57BL/6 mice were pretreated with streptomycin and then challenged with S. Typhimurium luxCDABE reporter strains containing promoter sig70_16 (A and D), sig70c10 (B and E), or sig70c35 (C and F). Mice were visualized on a whole-animal imager at 1 day postinfection (A, B, and C). At 4 to 5 days postinfection, mice were euthanized and their organs (spleen, liver, gastrointestinal [GI] tract [stomach, intestine, cecum, and colon], and MLN) were recovered and imaged (D, E, and F). Peak luciferase values (measured in cps) are indicated.

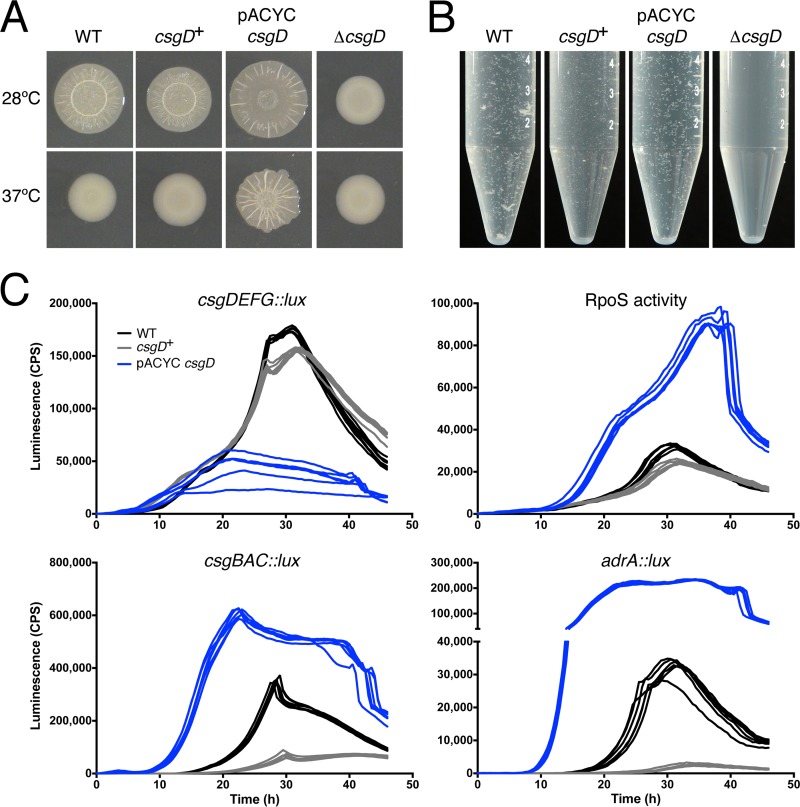

Chromosomal complementation of a S. Typhimurium ΔcsgD mutant strain.

We predicted that we could use the modified Tn7 system to complement an S. Typhimurium ΔcsgD strain at near-stoichiometric expression levels. Regulation of csgD expression is known to be complex, involving multiple transcriptional regulatory proteins, small RNAs (sRNAs), and histone-like proteins, such as H-NS and integration host factor (IHF) (42). With csgD and its native promoter inserted downstream of glmS in the chromosome, the resulting csgD+ strain (csgD+ at the attTn7 site and ΔcsgD in the native position in the chromosome) was compared to the ΔcsgD strain complemented from a plasmid (i.e., pACYC-csgD).

CsgD is the central regulator of biofilm development in Salmonella, and it controls several multicellular behaviors that have been collectively termed the red, dry, and rough (rdar) morphotype (43). Rdar morphotype colonies are adhesive, patterned colonies that can be lifted intact off the agar surface after 48 h of growth (26, 43). As expected, the WT S. Typhimurium 14028 strain formed rdar colonies, whereas the ΔcsgD mutant strain formed mucoid colonies (Fig. 6A). The colony morphology of the csgD+ strain closely matched that of the WT strain (Fig. 6A), which was consistent with production of curli fimbriae and cellulose, two of the extracellular matrix components that are regulated by CsgD (44). The pACYC-csgD strain yielded colonies that were larger and had a flatter appearance at 28°C (Fig. 6A) and were rdar-like at 37°C, which was consistent with overproduction of curli and cellulose (43). We also observed the phenotypes of each strain grown in liquid culture under biofilm-inducing conditions; cells are known to differentiate into multicellular aggregates (CsgD-ON state) and planktonic cells (CsgD-OFF state) (45, 46). Multicellular aggregates were formed in WT cultures and were notably absent in the ΔcsgD strain (Fig. 6B). Aggregates were visible in the csgD+ and pACYC-csgD strains, demonstrating that CsgD expression had been restored. However, the pACYC-csgD cultures appeared to be almost entirely devoid of planktonic cells (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material).

FIG 6.

Chromosome-based complementation of an S. Typhimurium ΔcsgD mutant strain. (A and B) S. Typhimurium ATCC 14028 (WT), ΔcsgD, csgD+, and pACYC-csgD strains were grown on 1% tryptone agar at 28°C or 37°C (A) or in 1% tryptone broth at 28°C (B). (C) csgDEFG, csgBAC, and adrA expression was measured during growth using promoter-luciferase (luxCDABE) fusion plasmids, designed to measure gene expression by light production (cps). RpoS activity was measured using the sig38H4::lux reporter plasmid, which contains a synthetic, RpoS-dependent promoter (26). Each line represents the expression curve from one biological replicate culture performed in triplicate, where cps was measured at half-hour intervals during growth. Cells were grown in 1% tryptone broth at 28°C with agitation; expression was measured in a Victor X3 multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer).

To quantitate the degree of CsgD complementation in each strain, we measured the expression of csgD and csgB, coding for curli fimbria production, and adrA, coding for a regulator of cellulose production, using promoter-lux operon fusion plasmids. In addition, the activity level of RpoS, a sigma factor that is known to regulate csgD expression and several downstream components, was monitored using a synthetic, RpoS-responsive promoter (26, 28). Transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis indicated that the presence of a luxCDABE fusion plasmid has only a minor effect on cell physiology (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material); therefore, these plasmids provide a good measure of real-time gene expression. Expression of csgD and the RpoS-responsive promoter matched closely between the WT and csgD+ strains during growth at 28°C (Fig. 6C). In contrast, the plasmid-complemented strain had a different csgD expression profile, and the RpoS activity was approximately three times higher (Fig. 6C, blue lines). Expression of csgB and adrA was similarly elevated in the pACYC-csgD strain (i.e., 2 times higher for csgB and 10 times higher for adrA) compared to the WT. In the csgD+ strain, csgB and adrA were expressed at lower levels, but the temporal profiles were similar to those in the WT strain (Fig. 6C). From this collection of experiments, we concluded that the chromosomally complemented strain had more stoichiometric CsgD expression than the plasmid-complemented strain.

DISCUSSION

We developed a more efficient Tn7 transposition system for use in Salmonella, E. coli, and other enterobacterial strains. Transposition was successful in 40 separate experiments when using our pHSG415-tnsABCD helper plasmid. In comparison to the preexisting Tn7 system, we did not achieve a single transposition event when using the nonreplicating helper plasmid pTNS2 (12) or pTNS3 (34). While these plasmids may still work if transformed via mating (47, 48), transposition is undoubtedly a rare event. The use of our helper plasmid resulted in 10- to 30-times-boosted tnsABCD expression compared to that with pTNS2 or pTNS3 and in transposition frequencies ranging from 10−8 to 10−10. pHSG415 is particularly useful because it is unstable in the absence of selection pressure (49); therefore, growth at 37°C without antibiotic should result in loss of the plasmid from 100% of cells. We also tested a helper and delivery combination plasmid that was specifically designed for use in Salmonella (i.e., pGRG25) (18). We found it difficult to clone into this large 12.5-kb vector, and once successful, we also did not achieve a single transposition event after 20 attempts. The only problem we encountered with pHSG415-tnsABCD was with an antibiotic-resistant E. coli poultry isolate that we were unable to select for transformants (A. Dar and B. Allan, unpublished data). Strain resistance could be overcome by introducing a new antibiotic resistance marker in pHSG415 or perhaps through use of an alternative helper plasmid (17). Our modified Tn7 system was recently used to generate luxCDABE-expressing strains of S. enterica serovar Enteritidis (S. Lam and W. Koester, unpublished data) and E. coli K-12 (S. Bernier and M. Surette, unpublished data) within 1 month of receipt of the plasmids. In theory, the use of the pHSG415-tnsABCD helper plasmid should allow for efficient Tn7 transposition in any bacterial species that can support replication of pSC101-based plasmids.

Reporter strains of E. coli and S. Typhimurium expressing bacterial luciferase or red or green fluorescent reporters were tested in combination with three synthetic, σ70-dependent promoters. Due to the ubiquity of σ70 during growth (50), expression was constitutive, and each promoter had similar temporal patterns that differed only in strength. The S. Typhimurium luciferase reporter strains provided stable expression throughout the infection of mice, and three different levels of expression were observed. However, we were unable to detect Salmonella during the middle stages of infection (i.e., days 2 to 4). It is possible that a stronger σ70-dependent promoter, perhaps with both −10 and −35 consensus sequences (51), will allow visualization at lower cell numbers. The three levels of expression provide flexibility to ensure that the proper balance between reporter signal and minimal impact on biological processes can be achieved. It should be noted that there is a published method using Tn7 to generate bioluminescent Salmonella strains, and these authors demonstrated that luciferase output was proportional to cell number (21); however, their system does not provide for the same flexibility that the pCS26-based system does. We have used pCS26 in the past to track the expression of various genes in vivo (32), but plasmid instability was a problem. The stochasticity of plasmid loss makes it difficult to form strong conclusions about the expression of different genes or to correlate with a specific number of bacterial cells. Now, with a system to easily integrate pCS26 constructs into the chromosome, expanded in vivo gene tracking experiments can be performed.

The E. coli and S. Typhimurium strains expressing fluorescent reporters were designed for future single-cell applications, for example, to analyze the dynamics within bacterial populations (52) or to study host-pathogen interactions (53). We demonstrated that these reporter strains could be detected with a 96-well plate reader, on solid medium using a whole-animal imager, and by confocal microscopy. Although there was differentiation between the σ70-dependent promoters, the dynamic range of the fluorescent reporters was far less than that of luciferase, which is consistent with previous studies comparing these reporters (54). GFP and mCherry can be used for whole-animal imaging experiments, but the autofluorescence from tissue and absorbance from specific cell molecules (e.g., hemoglobin) makes detection difficult (55). As a result, there has been a continual push to generate fluorescent reporters that have a lower background for whole-animal imaging, such as those that emit signals in the near-infrared range (i.e., >700 nm [56]). If new reporters do become available (9), they can easily be incorporated into the pCS26 system and used to generate new chromosomal reporter strains.

The use of both kanamycin and chloramphenicol resistance markers facilitates competition experiments between Salmonella or E. coli strains or between different bacterial species. We had initial concerns with use of the kanamycin marker for infection experiments, due to the potential overgrowth of normal flora isolates upon recovery, but we did not encounter any problems. If a researcher does encounter low-level resistance, our tests showed that the Knr and Cmr strains could be recovered equally well at higher antibiotic concentrations. We also generated a tetracycline-resistant pCS26 derivative, but luciferase expression was much higher and appeared to be unregulated (D. J. Shivak and A. P. White, unpublished data). It is assumed that insertion of transcriptional terminators upstream and downstream of the tetC gene would correct this problem, but we did not investigate this further.

Since the original publication of the Tn7 transposition method (12), it has proven to be an incredibly useful system. Modifications have been made in an attempt to improve the flexibility of the system (as described in the introduction) and to incorporate new aspects of gene expression analysis (57). The work we have described will add to the microbiologist tool box for researchers who study bacterial species within the Enterobacteriaceae, by providing great flexibility and the ability to combine with high-throughput expression experiments. The tnsABCD helper and mini-Tn7T delivery plasmids that we have generated will allow the development of chromosomal reporter strains in as little time as 2 to 4 weeks. These plasmids can be easily modified and are freely available upon request.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

K.D.M. was supported by a Canada Graduate Scholarship from NSERC, and D.J.S. and N.L.W. were supported by Research Awards from the University of Saskatchewan.

We are grateful to Don Wilson, Stew Walker, and the VIDO animal care staff for professional help with the animal experiments, to Melissa Palmer, George Mutwiri, and Elizabeth Brockman for laboratory assistance, and to Wei Xiao, Wolfgang Koester, and Shirley Lam for helpful discussions.

Funding Statement

This work, including the efforts of Aaron P. White, was funded by the Government of Canada, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) (386063-2010). This research was also supported through the Jarislowsky Chair in Biotechnology to A.P.W. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01346-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol 2:2006.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porwollik S, Santiviago CA, Cheng P, Long F, Desai P, Fredlund J, Srikumar S, Silva CA, Chu W, Chen X, Canals R, Reynolds MM, Bogomolnaya L, Shields C, Cui P, Guo J, Zheng Y, Endicott-Yazdani T, Yang HJ, Maple A, Ragoza Y, Blondel CJ, Valenzuela C, Andrews-Polymenis H, McClelland M. 2014. Defined single-gene and multi-gene deletion mutant collections in Salmonella enterica sv Typhimurium. PLoS One 9:e99820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santiviago CA, Reynolds MM, Porwollik S, Choi SH, Long F, Andrews-Polymenis HL, McClelland M. 2009. Analysis of pools of targeted Salmonella deletion mutants identifies novel genes affecting fitness during competitive infection in mice. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000477. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalir S, McClure J, Pabbaraju K, Southward C, Ronen M, Leibler S, Surette MG, Alon U. 2001. Ordering genes in a flagella pathway by analysis of expression kinetics from living bacteria. Science 292:2080–2083. doi: 10.1126/science.1058758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaslaver A, Mayo AE, Rosenberg R, Bashkin P, Sberro H, Tsalyuk M, Surette MG, Alon U. 2004. Just-in-time transcription program in metabolic pathways. Nat Genet 36:486–491. doi: 10.1038/ng1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mills E, Petersen E, Kulasekara BR, Miller SI. 2015. A direct screen for c-di-GMP modulators reveals a Salmonella Typhimurium periplasmic l-arginine-sensing pathway. Sci Signal 8:ra57. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaa1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhuri RR, Morgan E, Peters SE, Pleasance SJ, Hudson DL, Davies HM, Wang J, van Diemen PM, Buckley AM, Bowen AJ, Pullinger GD, Turner DJ, Langridge GC, Turner AK, Parkhill J, Charles IG, Maskell DJ, Stevens MP. 2013. Comprehensive assignment of roles for Salmonella typhimurium genes in intestinal colonization of food-producing animals. PLoS Genet 9:e1003456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kroger C, Colgan A, Srikumar S, Handler K, Sivasankaran SK, Hammarlof DL, Canals R, Grissom JE, Conway T, Hokamp K, Hinton JC. 2013. An infection-relevant transcriptomic compendium for Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium. Cell Host Microbe 14:683–695. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell-Valois FX, Sansonetti PJ. 2014. Tracking bacterial pathogens with genetically-encoded reporters. FEBS Lett 588:2428–2436. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Opijnen T, Camilli A. 2013. Transposon insertion sequencing: a new tool for systems-level analysis of microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol 11:435–442. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angelichio MJ, Camilli A. 2002. In vivo expression technology. Infect Immun 70:6518–6523. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6518-6523.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi KH, Gaynor JB, White KG, Lopez C, Bosio CM, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Schweizer HP. 2005. A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat Methods 2:443–448. doi: 10.1038/nmeth765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi KH, Schweizer HP. 2006. Mini-Tn7 insertion in bacteria with single attTn7 sites: example Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat Protoc 1:153–161. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters JE, Craig NL. 2001. Tn7: smarter than we thought. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2:806–814. doi: 10.1038/35099006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waddell CS, Craig NL. 1989. Tn7 transposition: recognition of the attTn7 target sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86:3958–3962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitra R, McKenzie GJ, Yi L, Lee CA, Craig NL. 2010. Characterization of the TnsD-attTn7 complex that promotes site-specific insertion of Tn7. Mob DNA 1:18. doi: 10.1186/1759-8753-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crepin S, Harel J, Dozois CM. 2012. Chromosomal complementation using Tn7 transposon vectors in Enterobacteriaceae. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:6001–6008. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00986-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKenzie GJ, Craig NL. 2006. Fast, easy and efficient: site-specific insertion of transgenes into enterobacterial chromosomes using Tn7 without need for selection of the insertion event. BMC Microbiol 6:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damron FH, McKenney ES, Schweizer HP, Goldberg JB. 2013. Construction of a broad-host-range Tn7-based vector for single-copy P(BAD)-controlled gene expression in gram-negative bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:718–721. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02926-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Damron FH, McKenney ES, Barbier M, Liechti GW, Schweizer HP, Goldberg JB. 2013. Construction of mobilizable mini-Tn7 vectors for bioluminescent detection of gram-negative bacteria and single-copy promoter lux reporter analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:4149–4153. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00640-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howe K, Karsi A, Germon P, Wills RW, Lawrence ML, Bailey RH. 2010. Development of stable reporter system cloning luxCDABE genes into chromosome of Salmonella enterica serotypes using Tn7 transposon. BMC Microbiol 10:197. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bjarnason J, Southward CM, Surette MG. 2003. Genomic profiling of iron-responsive genes in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium by high-throughput screening of a random promoter library. J Bacteriol 185:4973–4982. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.16.4973-4982.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White AP, Weljie AM, Apel D, Zhang P, Shaykhutdinov R, Vogel HJ, Surette MG. 2010. A global metabolic shift is linked to Salmonella multicellular development. PLoS One 5:e11814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaslaver A, Bren A, Ronen M, Itzkovitz S, Kikoin I, Shavit S, Liebermeister W, Surette MG, Alon U. 2006. A comprehensive library of fluorescent transcriptional reporters for Escherichia coli. Nat Methods 3:623–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson TJ, Kariyawasam S, Wannemuehler Y, Mangiamele P, Johnson SJ, Doetkott C, Skyberg JA, Lynne AM, Johnson JR, Nolan LK. 2007. The genome sequence of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain O1:K1:H7 shares strong similarities with human extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli genomes. J Bacteriol 189:3228–3236. doi: 10.1128/JB.01726-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White AP, Gibson DL, Kim W, Kay WW, Surette MG. 2006. Thin aggregative fimbriae and cellulose enhance long-term survival and persistence of Salmonella. J Bacteriol 188:3219–3227. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.9.3219-3227.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis KN. 1990. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol 172:6557–6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White AP, Surette MG. 2006. Comparative genetics of the rdar morphotype in Salmonella. J Bacteriol 188:8395–8406. doi: 10.1128/JB.00798-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westerlund-Karlsson A, Saviranta P, Karp M. 2002. Generation of thermostable monomeric luciferases from Photorhabdus luminescens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 296:1072–1076. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell RJ, Ahn J, Gu MB. 2005. Comparison of Photorhabdus luminescens and Vibrio fischeri lux fusions to study gene expression patterns. J Microbiol Biotechnol 15:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim W, Surette MG. 2004. Metabolic differentiation in actively swarming Salmonella. Mol Microbiol 54:702–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White AP, Gibson DL, Grassl GA, Kay WW, Finlay BB, Vallance BA, Surette MG. 2008. Aggregation via the red, dry, and rough morphotype is not a virulence adaptation in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun 76:1048–1058. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01383-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hashimoto-Gotoh T, Franklin FC, Nordheim A, Timmis KN. 1981. Specific-purpose plasmid cloning vectors. I. Low copy number, temperature-sensitive, mobilization-defective pSC101-derived containment vectors. Gene 16:227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi KH, Mima T, Casart Y, Rholl D, Kumar A, Beacham IR, Schweizer HP. 2008. Genetic tools for select-agent-compliant manipulation of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:1064–1075. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02430-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maloy SR, Stewart VJ, Taylor RK. 1996. Genetic analysis of pathogenic bacteria: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barthel M, Hapfelmeier S, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kremer M, Rohde M, Hogardt M, Pfeffer K, Russmann H, Hardt WD. 2003. Pretreatment of mice with streptomycin provides a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium colitis model that allows analysis of both pathogen and host. Infect Immun 71:2839–2858. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2839-2858.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang AC, Cohen SN. 1978. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol 134:1141–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim W, Surette MG. 2006. Coordinated regulation of two independent cell-cell signaling systems and swarmer differentiation in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 188:431–440. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.431-440.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keestra-Gounder AM, Tsolis RM, Baumler AJ. 2015. Now you see me, now you don't: the interaction of Salmonella with innate immune receptors. Nat Rev Microbiol 13:206–216. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steenackers H, Hermans K, Vanderleyden J, De Keersmaecker SCJ. 2012. Salmonella biofilms: an overview on occurrence, structure, regulation and eradication. Food Res Int 45:502–531. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.01.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romling U, Sierralta WD, Eriksson K, Normark S. 1998. Multicellular and aggregative behaviour of Salmonella typhimurium strains is controlled by mutations in the agfD promoter. Mol Microbiol 28:249–264. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zogaj X, Nimtz M, Rohde M, Bokranz W, Romling U. 2001. The multicellular morphotypes of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli produce cellulose as the second component of the extracellular matrix. Mol Microbiol 39:1452–1463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grantcharova N, Peters V, Monteiro C, Zakikhany K, Römling U. 2010. Bistable expression of CsgD in biofilm development of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. J Bacteriol 192:456–466. doi: 10.1128/JB.01826-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacKenzie KD, Wang Y, Shivak DJ, Wong CS, Hoffman LJ, Lam S, Kroger C, Cameron AD, Townsend HG, Koster W, White AP. 2015. Bistable expression of CsgD in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium connects virulence to persistence. Infect Immun 83:2312–2326. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00137-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arena ET, Auweter SD, Antunes LC, Vogl AW, Han J, Guttman JA, Croxen MA, Menendez A, Covey SD, Borchers CH, Finlay BB. 2011. The deubiquitinase activity of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 effector, SseL, prevents accumulation of cellular lipid droplets. Infect Immun 79:4392–4400. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05478-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sham HP, Shames SR, Croxen MA, Ma C, Chan JM, Khan MA, Wickham ME, Deng W, Finlay BB, Vallance BA. 2011. Attaching and effacing bacterial effector NleC suppresses epithelial inflammatory responses by inhibiting NF-kappaB and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. Infect Immun 79:3552–3562. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05033-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caulcott CA, Dunn A, Robertson HA, Cooper NS, Brown ME, Rhodes PM. 1987. Investigation of the effect of growth environment on the stability of low-copy-number plasmids in Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol 133:1881–1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gruber TM, Gross CA. 2003. Multiple sigma subunits and the partitioning of bacterial transcription space. Annu Rev Microbiol 57:441–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gaal T, Ross W, Estrem ST, Nguyen LH, Burgess RR, Gourse RL. 2001. Promoter recognition and discrimination by EsigmaS RNA polymerase. Mol Microbiol 42:939–954. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Locke JC, Elowitz MB. 2009. Using movies to analyse gene circuit dynamics in single cells. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:383–392. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Avraham R, Haseley N, Brown D, Penaranda C, Jijon HB, Trombetta JJ, Satija R, Shalek AK, Xavier RJ, Regev A, Hung DT. 2015. Pathogen cell-to-cell variability drives heterogeneity in host immune responses. Cell 162:1309–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Jong H, Ranquet C, Ropers D, Pinel C, Geiselmann J. 2010. Experimental and computational validation of models of fluorescent and luminescent reporter genes in bacteria. BMC Syst Biol 4:55. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Troy T, Jekic-McMullen D, Sambucetti L, Rice B. 2004. Quantitative comparison of the sensitivity of detection of fluorescent and bioluminescent reporters in animal models. Mol Imaging 3:9–23. doi: 10.1162/153535004773861688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Filonov GS, Piatkevich KD, Ting LM, Zhang J, Kim K, Verkhusha VV. 2011. Bright and stable near-infrared fluorescent protein for in vivo imaging. Nat Biotechnol 29:757–761. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bruckbauer ST, Kvitko BH, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Schweizer HP. 2015. Tn5/7-lux: a versatile tool for the identification and capture of promoters in gram-negative bacteria. BMC Microbiol 15:17. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0354-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.