Abstract

Significant changes in the shape, size and position of the bladder during radiotherapy (RT) treatment for bladder cancer have been correlated with high local failure rates; typically due to geographical misses. To account for this, large margins are added around the target volumes in conventional RT; however, this increases the volume of healthy tissue irradiation. The availability of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) has not only allowed in‐room volumetric imaging of the bladder, but also the development of adaptive radiotherapy (ART) for modification of plans to patient‐specific changes. The aim of this review is to: (1) identify and explain the different ART techniques being used in clinical practice and (2) compare and contrast these different ART techniques to conventional RT in terms of target coverage and dose to healthy tissue: A literature search was conducted using EMBASE, MEDLINE and Scopus with the key words ‘bladder, adaptive, radiotherapy/radiation therapy’. 11 studies were obtained that compared different adaptive RT techniques to conventional RT in terms of target volume coverage and healthy tissue sparing. All studies showed superior target volume coverage and/or healthy tissue sparing in adaptive RT compared to conventional RT. Cross‐study comparison between different adaptive techniques could not be made due to the difference in protocols used in different studies. However, one study found daily re‐optimisation of plans to be superior to plan of the day technique. The use of adaptive RT for bladder cancer is promising. Further study is required to assess adaptive RT versus conventional RT in terms of local control and long‐term toxicity.

Keywords: Adaptive, bladder, cone beam computed tomography, conventional, radiation therapy

Introduction

According to 2000–2010 Australian incidence data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), bladder cancer is the seventh most diagnosed cancer in men and the fifteenth most diagnosed cancer in women.1 The current gold standard for bladder preservation treatment is a multimodality approach combining transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT), neoadjuvant and concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy.2, 3, 4 Radical cystectomy was regarded as the first‐line therapy for bladder cancer, however, this leaves patients without an intact bladder requiring further surgery for bladder reconstruction.2 Although radiotherapy can result in radiation‐induced toxicity, it is an alternative to radical cystectomy with comparable outcome and the added benefit of leaving a functional bladder.5

The size and shape of the bladder varies constantly due to bladder and rectal filling, posing a great challenge in radiotherapy treatment delivery.2, 4, 6 The dynamic nature of the bladder during the course of treatment is complex to address as it can result in geographical misses leading to under dosing the target volume and overdosing healthy tissue hence decreasing the therapeutic ratio.7, 8 Therefore, image guidance to accurately verify and localise the target volume before treatment delivery is crucial. Conventionally, bony anatomy has been used, however, the dynamic nature of the bladder necessitates that a clinical target volume to planning target volume (CTV‐PTV) margin of >2 cm be applied.4, 8, 10, 13 Furthermore, despite the CTV expansion, studies have shown that the CTV coverage is often not adequate and this may decrease the probability of local tumour control.11, 13

Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) has allowed 3D imaging with the patient in the treatment position and the individualisation of treatment through adaptive radiotherapy (ART). CBCT images are acquired during or immediately prior to treatment delivery and treatment plans are evaluated and modified for patient‐specific changes.11 There are several different ART techniques reported in the literature. These will be identified and explained as part of this review with the aim of helping departments considering implementing ART for bladder cancer to understand the different ART methods available. This review then aims to compare and contrast the single plan conventional radiotherapy to the different ART techniques used for bladder cancer in terms of target coverage and healthy tissue sparing.

Methods

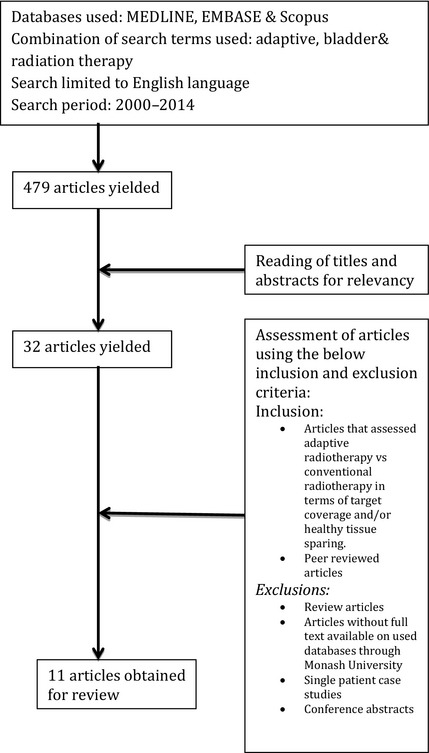

The initial literature search was performed by both authors, using MEDLINE, EMBASE and Scopus databases. The search terms used were a combination of bladder, adaptive and radiotherapy/radiation therapy. The search was limited to English language articles only and studies conducted from 2000 to 2014. This yielded a total of 479 articles that were subsequently screened using their title and abstract to identify original articles that directly compared conventional radiotherapy techniques to at least one ART technique for bladder cancer. Duplicate articles were removed. This yielded 32 relevant articles. Stage two of the review strategy identified articles that reported a comparison in target coverage and/or healthy tissue sparing between conventional RT and ART in their results. Of these, only peer reviewed articles that were available in full text were included. Single‐patient case studies, conference abstracts and review articles were excluded. This yielded a final total of 11 articles to be included for review. The literature search method is demonstrated in the flow diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of method used to obtain articles for the review.

Results

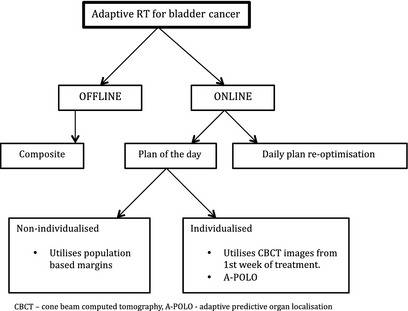

The literature identified several different ART techniques used in clinical practice. Adaptive RT techniques have been categorised into two main groups, offline and online. The online technique has been further subdivided as shown in the schematic diagram in Figure 2. Based on these ART classifications, the results of the 11 articles identified in this review are presented in Table 1. Seven studies compared adaptive RT and conventional RT in terms of both healthy tissue sparing and target volume coverage,14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20 while the other four studies investigated normal tissue sparing only.21, 22, 23, 24 Each ART technique will now be explained, followed by a comparison of ART to conventional single‐plan techniques.

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram showing the different adaptive radiation therapy techniques described in the studies reviewed.

Table 1.

Studies comparing adaptive radiotherapy (ART) to conventional radiotherapy

| Reference | Patient no. | ART technique | Treatment technique | ART |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos et al.15 | 21 | Composite | 3D‐CRT + daily CBCT for 1st week then weekly CBCT |

|

| Foroudi et al.14 | 5 | Composite | 3D‐CRT + daily CBCT for 1st week then weekly CBCT |

Composite – 2/5 patients required adaptive planning with minimum CTV coverage improved from 60.1% to 94.7% isodose coverage and 96.3% to 98.1% in the second patient Lower rectal D50 for ART compared to Conv RT |

| Webster et al.16 | 20 |

Composite 1 Composite 2 and non‐individualised plan of the day (PoD) |

3D‐CRT Daily CBCT for 1st 3 fractions Then weekly CBCT 3D‐CRT Daily CBCT |

Compared to ConvRT, mean irradiated volume was reduced by 17.2%, 35.0% and 14.6% for PoD, Composite 1 and Composite 2 respectively PoD improved target coverage compared to ConvRT Composite 1 compromised target coverage compared to conventional Composite 2 showed no benefit in target coverage compared to Conventional |

| Burridge et al.21 | 20 | Non‐individualised PoD | 3D‐CRT + daily CBCT for 1st week then weekly CBCT | 31 ± 23 cm3 small bowel spared compared to ConvRT |

| Vestergaard et al. 17 | Non‐individualised PoD and individualised PoD with 1st 5 CBCT | IMRT + daily CBCT |

Mean ratio of volume receiving >95% of prescribed dose when compared to conventional = 0.66 and 0.67 for non‐ individualised and individualised PoD respectively ≥ comparable In general ART technique reduced treatment volume by 40% compared to conventioanl |

|

| Foroudi et al.18 | 27 | Individualised PoD with 1st 5 CBCT | 3D‐CRT + daily CBCT |

V95 < 99% in 2.7% of fractions in ART method V95 < 99% in 4.8% of fractions in non‐ART fractions 29% reduction in mean normal tissue volume receiving >45% |

| Tolan et al.19 | 11 | Individualised PoD with 1st 5 CBCT | 3D‐CRT + daily CBCT | 2 out of 3 individualised plans, incorporated 99% of the bladder position & resulted in reduction of irradiated volume 426–440 cm3 compared to 914 cm3 in conventional plans |

| Tuomikoski et al.22 | 5 | A‐POLO PoD | IMRT + daily CBCT | Intestinal cavity reduced from 335 to 180cm3 compared to ConvRT |

| McDonald et al.20 | 27 | A‐POLO PoD | 3D‐CRT + daily CBCT |

|

| Lalondrelle et al.23 | 15 | A‐POLO PoD | 3D‐CRT + daily CBCT | Target coverage improved by 24% from 49% to 73% of fractions delivered correctly |

| Vestergaard et al.24 | 7 | Online re‐optimisation and PoD |

VMAT + daily CBCT IMRT + daily CBCT |

Compared to ConvRT, volume receiving >95% of prescribed dose was reduced to 66% in PoD technique and 41% in Re‐optimisation technique |

PoD, plan of the day; 3D‐CRT, 3D conformal radiotherapy; IMRT, intensity‐modulated radiotherapy; CBCT, cone beam computed tomography; VMAT, volumetric‐modulated arc therapy; A‐POLO, adaptive predictive organ localisation; ConvRT, conventional radiotherapy; ART, adaptive radiotherapy; GTV, gross tumour volume, CTV, clinical target volume.

Offline ART

Composite ART technique – compared to conventional RT

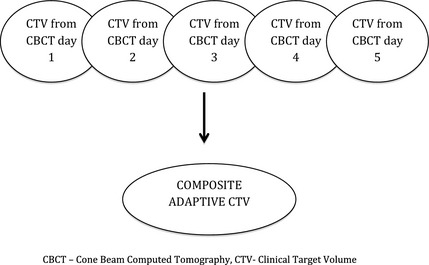

Two studies14, 15 applied the offline/composite method for ART. This involved use of the CBCT images acquired in the first week of treatment to create a new adaptive CTV (Fig. 3) and a target volume more representative of the patients’ organ size, shape and position during the treatment period. Pos et al.,15 showed that composite ART technique for bladder cancer in 21 patients reduced PTV volume by 40% compared to conventional non‐adaptive RT, while maintaining adequate target volume coverage. Foroudi et al.,14 showed that two of five patients benefited from a composite ART technique with CTV coverage, improving from a minimum of 60.1–94.7% in one patient and 96.3–98.1% in the second patient. Although the results of this study using such a small sample size were not able to provide statistical significance, they do demonstrate the potential benefit of using ART. The composite technique also showed a higher conformity index compared to conventional in 95% isodose distribution around the CTV.15 Furthermore, the composite ART technique resulted in lower rectal D50 (dose received by 50% of the rectum volume) compared to the conventional plan.14

Figure 3.

A schematic diagram of the technique used to create a composite adaptive radiotherapy plan. The five top nodes represent CBCT images taken during week 1 and the resulting node represents the composite plan produced using the CBCT images to create a plan that is more representative of a patient's bladder shape and size. CBCT, cone beam computed tomography; CTV, clinical target volume.

Another study that looked at composite ART technique was by Webster et al.16 who created two composite plans by applying 5‐ and 10‐mm isotropic margins (composite 1 and composite 2, respectively). The study showed that composite 1 compromised target coverage compared to convention RT. Composite 2 did not show any significant advantage in target coverage compared to conventional RT. However, both composite techniques had healthy tissue sparing benefits by reducing the irradiated volume. Therefore, the conclusion can be made that composite ART technique is superior to conventional RT in increasing the therapeutic ratio. It is also evident that a CTV‐PTV margin of >5 mm is required for composite techniques to be beneficial compared to conventional RT. However, the optimal CTV‐PTV margin for composite techniques was not investigated in this study and should be considered for inclusion in future studies. Furthermore, there was a reduced number of CBCT scans used to create ART plans in the Webster et al.16 study compared to the Pos et al.15 and Foroudi et al.14 studies. It is not clear whether an additional two CBCT images would have made a difference in target coverage in the study by Webster et al.16 but further research is required to determine the optimal number of images required to create ART plans.

One contributing factor to these non‐statistically significant results may have been the small sample size (five) in the Foroudi et al.14 study, however, as mentioned previously, they did show a significant reduction in healthy tissue irradiated.14 Webster et al.16 used a different methodology to create their composite ART plans. Using the first three CBCT images, rather than the first five CBCT images, they concluded that conventional RT was superior to composite ART in target volume coverage. However, the reduced number of CBCT images may have resulted in composite ART plans that did not represent the full range of bladder volume variation throughout a treatment course.

The limitations of the composite ART technique are that it mainly accounts for systematic errors that might have occurred between planning and treatment period and does not account for random daily bladder volume changes. It is, however, easier to implement as it has the least impact in terms of extra time required and technical requirements for staff.

Online ART

Nine studies applied online adaptive RT techniques using three different techniques as explained below:

PoD selection

The Plan of the Day (PoD) ART technique requires a library of plans to be created, and after acquiring a daily CBCT, the best fit plan for that fraction is selected based on the daily bladder volume. The methods used for the plan library creation required in this technique also vary. Techniques using population‐based margins as well as individualised plan library were identified.

Non‐individualised ‘PoD’ compared to conventional RT

Two studies17, 21 applied a non‐individualised PoD technique by applying population‐based isotropic or anisotropic margins around the CTV from planning CT to create the PTV. Burridge et al.21 was the first to investigate online adaptive RT in bladder cancer patients. They created a library of plans using only the planning CT images. After delineating the bladder as the CTV, they produced one plan by adding a uniform 15‐mm CTV‐PTV margin (as per conventional protocol) and then created two more PTV volumes by varying the margin in the superior direction to the CTV to create a selection of three PoD plans. During treatment, a CBCT image was taken prior to treatment and a PTV was chosen from the three available plans that adequately covered the bladder with a 2‐mm clearance. This PoD technique lead to a mean PTV reduction of 31 cm3 compared to the conventional plan of isotropic 15‐mm margin around the CTV. A similar method was used by Vestergaard et al.,17 who also created a non‐individualised library of plans using population‐based margins. They found that the non‐individualised PoD technique reduced the treatment volume by up to 40% compared to the conventional RT.

The non‐individualised PoD method showed a mean PTV reduction and reduced irradiation of healthy tissue in the superior direction compared to the conventional RT, suggesting reduced small bowel irradiation and hence reduced small bowel toxicity17, 21 These results are supported by a study done by Murthy et al.25 who also used non‐individualised margins by increasing the CTV by 5–30 mm in 5‐mm increments, hence creating six plans per patient for all the 10 patients. They found that 99.4% of fractions required plans with 5–15‐mm PTV margin, and they also found that three to four plans were adequate to cover target volume through the treatment period when using this method.

Individualised ‘PoD’ compared to conventional RT

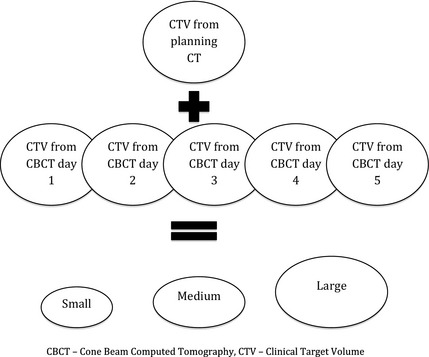

The individualised PoD technique creates a plan library that is individually tailored rather than using population‐based margins. There were two different ways identified in the literature to individualise the plan library. The first acquired daily CBCT during the first week of treatment and then created a patient‐specific library of small, medium and large PTV plans that could be applied to each subsequent fraction in the treatment course to fit the daily bladder volume (Fig. 4). Three studies17, 18, 19 applied this method and compared the outcome to conventional bladder RT. As seen in Table 1, Foroudi et al.18 found V95 (volume receiving 95% of the treatment dose of 64 Gy)to be <99% in 2.7% of the fractions treated in the individualised ART techniques compared to 4.8% of the fractions treated using the conventional technique. Furthermore, they also found a 29% reduction in mean healthy tissue receiving greater than 45% of the prescribed dose. Vestergaard et al.17 used a similar method to create their plan library and found a treatment volume reduction of 40% compared to conventional method. Tolan et al.19 showed that two out of three plans resulted in reduction of irradiated volume to 426–440 cm3 compared to 914 cm3 in conventional plans.

Figure 4.

A schematic diagram of the process to create an online individualised plan library for the ‘plan of the day’ adaptive technique using CBCT images from week 1 of treatment. This creates a library of plans with small, medium and large planning target volumes for each patient. CBCT, cone beam computed tomography; CTV, clinical target volume.

This PoD technique has demonstrated a significant reduction in healthy tissue irradiated compared to conventional RT.17, 18, 19 One study directly comparing the composite ART to the individualised PoD ART technique was conducted by Webster et al.16 who compared the two methods to conventional RT in terms of target coverage and volume of irradiated healthy tissue. They identified that although the composite plan with a 5‐mm margin had the greatest reduction in irradiated volume compared to PoD, 35% versus 17%, the composite plan compromised target coverage. They also found that a composite technique with a 10‐mm CTV‐PTV margin had comparable results to conventional RT in terms of target volume coverage but superior in healthy tissue sparing. The PoD technique proved to be superior with better target coverage compared to conventional RT as well as increased healthy tissue sparing compared to both the conventional and composite technique. Therefore, it can be concluded that PoD method had the optimal balance between target coverage and healthy tissue sparing.16

The other method reported in three studies20, 22, 23 was the adaptive predictive organ localisation (A‐POLO) method to individualise the library of plans. In this method all volumes were acquired during the planning stage. Patients were required to first void their bladder then drink a specified amount of water. Three planning CT scans were taken starting immediately after drinking water then at 15–20‐min intervals providing a range of possible bladder shapes and sizes that were used to create a library of plans. All three studies showed mean reduction in the volume of healthy tissue irradiated compared to conventional RT without compromising the mean CTV coverage by the 95% isodose line. McDonald et al.20 showed a 219‐cm3 mean volume reduction in healthy tissue compared to conventional RT without compromising CTV coverage. Lolondrelle et al.23 found that target coverage was improved by 24% using the A‐POLO technique compared to conventional RT. Toumikoski et al.22 found that the volume of bowel irradiated reduced from 335 cm3 to 180 cm3 compared to conventional RT.

All studies using the individualised plan library for the PoD method have shown an advantage over the conventional RT method in both healthy organ sparing and superior target volume coverage. However, the major advantage of the A‐POLO method over the use of the first five CBCT images for development of the plan libraries is that, in addition to the library of plans being patient specific, they are planned prior to commencement of treatment. This gives the additional advantage of the PoD selection method being applied from day one of treatment as opposed to waiting until week two or three.

Daily re‐optimisation compared to conventional RT

Daily plan re‐optimisation is the most recently reported online ART technique, whereby the plan is re‐optimised daily after acquisition of the CBCT. Theoretically this method would be expected to maximise accuracy and dose conformity. Its uptake, however, appears to be limited with only one article identified in this review.24 This study applied both PoD and daily plan re‐optimisation and compared them to conventional RT. This was the only study that compared results between 2 ART techniques. Both techniques achieved significant sparing of healthy tissue compared to conventional RT, however, daily re‐optimisation proved to be superior to the PoD method. They found that the volume receiving greater than 95% of the prescribed dose was reduced by 41% in the re‐optimisation technique compared to conventional RT and by 66% compared to the PoD method. This study used volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) for the daily re‐optimisation method and intensity‐modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) for the PoD method. The different planning techniques could have affected conformity of the plans produced, which might have affected the overall results.

Although the potential of daily plan re‐optimisation looks promising, the financial, logistical and technical burden it would impose in a radiotherapy department may be impacting the uptake of this method in routine clinical practice. In order to be clinical feasible, provisions would need to be made including intensive ART training programmes for the MDT team, a comprehensive QA process and consideration of work flow to allow for the extra time required for plan re‐optimisation.24 The recent availability of advanced treatment techniques such as VMAT could decrease treatment time to compensate for the additional time required for plan re‐optimisation and as such daily re‐optimisation may become increasingly viable.

Discussion

Bladder RT is complicated due to the dynamic nature of the bladder, with changes in shape and size during the treatment period. Conventional RT techniques require a large CTV‐PTV margin to compensate for bladder volume variations, hence the potential for irradiation of large volumes of healthy tissue. Adaptive radiotherapy is a method developed to overcome this. In this review, different offline and online ART strategies have been explained and compared to conventional methods of bladder radiotherapy in terms of target volume coverage and healthy tissue sparing. All ART studies included in this review demonstrated improved health tissue sparing. Five out of seven studies demonstrated superior target volume coverage. The two studies14, 16 that did not show target volume coverage to be superior in ART both used the offline composite plan technique. Even after considering the limitations of these offline studies discussed previously, these results suggest that this technique offers the least potential benefit to patients. Conversely, daily re‐optimisation appears to offer the greatest potential benefit to patients.

A limitation of this review is the small number of studies available that are comparing ART versus conventional RT in terms of target coverage and healthy tissue sparing. Furthermore, all the studies had a low number of patients with a maximum of 27. All studies were also single‐centre studies. Cross‐study comparisons were difficult to make due to the different ART treatment protocols used. As such, a direct comparison of the different adaptive techniques was not possible hence no recommendation could be provided as to the optimal ART technique. However, it can be concluded that all the ART techniques identified in this review were superior to the conventional non‐adaptive RT in sparing healthy tissue. It is also recognised that other resource factors will affect each department's decision on which ART technique best suits them, but analysing these factors is outside the scope of this review.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The availability of advanced imaging modalities such as CBCT has allowed for implementation of adaptive RT for bladder cancer. This review has provided a comprehensive overview of the available ART techniques in the treatment of bladder cancer. ART has increased dose conformity in bladder radiotherapy that has been difficult to achieve with conventional radiotherapy. The studies presented have shown that all the adaptive RT techniques are superior to the conventional RT technique and achieve a better therapeutic ratio. The superior target volume coverage and increased healthy tissue sparing suggest better tumour control and reduce long‐term radiation‐induced toxicity. However, there is minimal studies conducted comparing adaptive with conventional RT in terms of tumour control and toxicity therefore further research in this area is suggested. Furthermore, although all the adaptive RT techniques showed to be superior to the conventional RT, there needs to be further research conducted to directly compare these ART techniques. However, until such results are available, it is recommended that clinical departments intending to implement ART for bladder cancer evaluate each of the techniques presented in this review and balance the benefits and operational requirements of each ART technique against the available resources.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

None.

J Med Radiat Sci 62 (2015) 277–285

References

- 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Australasian Association of Cancer Registries . Cancer in Australia: An overview 2012. Cancer series no. 74. Cat. no. CAN 70. AIHW, Canberra, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thariat J, Aluwini S, Pan Q, et al. Image‐guided radiation therapy for muscle‐invasive bladder cancer. Nat Rev Urol 2012; 9: 23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harris VA, McDonald FMA, Huddart R. Latest advances in cone‐beam CT for bladder radiotherapy. Imaging Med 2011; 3: 321–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arthur C, Livsey J, Choudhury A. Delivering adaptive radiotherapy to the bladder during radical treatment. J Radiother Pract 2013; 12: 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kotwal S, Choudhury A, Johnston C, Paul AB, Whelan P, Kiltie AE. Similar treatment outcomes for radical cystectomy and radical radiotherapy in invasive bladder cancer treated at a United Kingdom specialist treatment center. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008; 70: 456–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meijer GJ, Rasch C, Remeijer P, Lebesque JV. Three‐dimensional analysis of delineation errors, setup errors, and organ motion during radiotherapy of bladder cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003; 55: 1277–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fokdal L, Honore H, Hoyer M, Meldgaard P, Fode K, von der Maase H. Impact of changes in bladder and rectal filling volume on organ motion and dose distribution of the bladder in radiotherapy for urinary bladder cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004; 59: 436–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foroudi F, Pham D, Bressel M, et al. Bladder cancer radiotherapy margins: A comparison of daily alignment using skin, bone or soft tissue. Clin Oncol 2012; 24: 673–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Muren LP, Smaaland R, Dahl O. Organ motion, set‐up variation and treatment margins in radical radiotherapy of urinary bladder cancer. Radiother Oncol 2003; 69: 291–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Redpath AT, Muren LP. CT‐guided intensity‐modulated radiotherapy for bladder cancer: Isocentre shifts, margins and their impact on target dose. Radiother Oncol 2006;81:276–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hutton D, Leadbetter J, Jain P, Baker A. Does one size fit all? Adaptive radiotherapy for bladder cancer: A feasibility study. Radiography 2013; 19: 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pos F, Remeijer P. Adaptive management of bladder cancer radiotherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol 2010; 20: 116–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pos FJ, Koedooder K, Hulshof MC, van Tienhoven G, Gonzalez Gonzalez D. Influence of bladder and rectal volume on spatial variability of a bladder tumor during radical radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003; 55: 835–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Foroudi F, Wong J, Haworth A, et al. Offline adaptive radiotherapy for bladder cancer using cone beam computed tomography: Radiation oncology ‐ Original article. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 53:226–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pos FJ, Hulshof M, Lebesque J, et al. Adaptive radiotherapy for invasive bladder cancer: A feasibility study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006; 64: 862–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Webster GJ, Stratford J, Rodgers J, Livsey JE, Macintosh D, Choudhury A. Comparison of adaptive radiotherapy techniques for the treatment of bladder cancer. Br J Radiol 2013; 86: 20120433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vestergaard A, Søndergaard J, Petersen JB, Høyer M, Muren LP. A comparison of three different adaptive strategies in image‐guided radiotherapy of bladder cancer. Acta Oncol 2010; 49: 1069–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Foroudi F, Wong J, Kron T, et al. Online adaptive radiotherapy for muscle‐invasive bladder cancer: Results of a pilot study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011; 81: 765–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tolan S, Kong V, Rosewall T, et al. Patient‐specific PTV margins in radiotherapy for bladder cancer ‐ a feasibility study using cone beam CT. Radiother Oncol 2011; 99: 131–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McDonald F, Lalondrelle S, Taylor H, et al. Clinical implementation of adaptive hypofractionated bladder radiotherapy for improvement in normal tissue irradiation. Clin Oncol 2013; 25: 549–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burridge N, Amer A, Marchant T, et al. Online adaptive radiotherapy of the bladder: Small bowel irradiated‐volume reduction. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006; 66: 892–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tuomikoski L, Collan J, Keyriläinen J, Visapää H, Saarilahti K, Tenhunen M. Adaptive radiotherapy in muscle invasive urinary bladder cancer ‐ An effective method to reduce the irradiated bowel volume. Radiother Oncol 2011; 99: 61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lalondrelle S, Huddart R, Warren‐Oseni K, et al. Adaptive‐predictive organ localization using cone‐beam computed tomography for improved accuracy in external beam radiotherapy for bladder cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011; 79: 705–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vestergaard A, Muren LP, Sondergaard J, Elstrom UV, Høyer M, Petersen JB. Adaptive plan selection vs. re‐optimisation in radiotherapy for bladder cancer: A dose accumulation comparison. Radiother Oncol 2013; 79: 705–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Murthy V, Master Z, Adurkar P, et al. ‘Plan of the day’ adaptive radiotherapy for bladder cancer using helical tomotherapy. Radiother Oncol 2011; 99: 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]