Abstract

The mounting evidence that R-genes incur large fitness costs raises a question: how can there be a 5-10% fitness reduction for all 149 R-genes in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome? The R-genes tested to date segregate for insertion-deletion (indel) polymorphisms where susceptible alleles are complete deletions. Since costs of resistance are measured as the differential fitness of isolines carrying resistant and susceptible alleles, indels reveal costs that may be masked when susceptible alleles are expressed. Rps2 segregates for two expressed clades of alleles, one resistant and one susceptible. Plants with resistant Rps2 are not less fit than those with a susceptible Rps2 allele in the absence of disease. Instead, all alleles provide a fitness benefit relative to an artificial deletion, due to the role of RPS2 as a negative regulator of defense. Our results highlight the interplay between genomic architecture and the magnitude of costs of resistance.

Understanding how plants maximize fitness in response to intermittent pathogen presence is of central importance in plant pathology. Natural plant pathosystems frequently involve long-maintained polymorphisms for host resistance1-3, and current theory on the maintenance of stable resistance polymorphisms requires costs of resistance and/or virulence acting in combination with frequency dependent selection4. In contrast, in agricultural contexts, resistance genes often have useful lifespans of only a few years and high costs of resistance are undesirable due to their negative effects on plant performance5. Pathogen resistance may involve two distinct fitness costs. The first, which we term a cost of surveillance, accrues from harboring R-genes that allow a resistance response upon attack6, and the second, a cost of defense, accrues from activation of the resistance response during attack6,7.

A cost of surveillance is measured in the absence of disease and has been determined for two R-genes, Rps5 and Rpm1, in Arabidopsis thaliana8,9. Rps5 exists in nature as a long-lived insertion-deletion polymorphism (indel) for resistance (R) and susceptibility (S)1,10,11; Rpm1 similarly exists as a long-lived indel polymorphism, though secondarily disrupted S alleles are also present within the resistance clade12. In both cases, resistant isolines suffer a 5-10% fitness cost relative to null isolines8,9. However, costs of this magnitude would correspond to an impossibly high genetic load if seen for all, or many, of the ~149 R-genes in A. thaliana. We propose that indels are an architecture with unusually high costs of surveillance. Null alleles of indels cannot carry any burden of mis-expression or mis-activation that would reduce relative costs of carrying resistant versus susceptible alleles. Furthermore, null alleles do not have the potential to evolve pleiotropic or alternative functions, another means of ameliorating costs of surveillance. R-genes are found with a great diversity of genetic architectures, including single loci with many, functional alleles and arrays of tandem duplicated R-genes13. Here, we explore the possibility that R-gene genetic architectures with alternative functional alleles have substantially smaller costs than those of the indels Rpm1 and Rps5. We posit that the large costs associated with these two R-genes are precisely the reason susceptible alleles are deleted.

Rps2 exists as an ancient balanced polymorphism with two long-lived clades of alleles, one resistant and one susceptible to Pseudomonas syringae pv. avrRpt214,15. Both clades are maintained at intermediate frequencies in local populations16. Rps2 is also present in every accession sequenced to date17. To measure the surveillance cost associated with resistant alleles of Rps2, we assayed fitness in the absence of disease for a transgenically-created allelic series of Rps2 that controls for the insertion site of the R-gene alleles18. We extended the basic strategy of using a Cre-lox system to compare isolines with and without a resistant allele (as done for Rpm18 and Rps59) to precisely integrate five alleles of Rps2 into the same genomic location. These alleles were inserted into a Col-0 genetic background in which Rps2 had been knocked out15. We additionally verified the robustness of our results by using three genomic locations for the insertion of Rps2. Our results reveal a bidirectional interplay between genomic architecture and fitness costs of resistance.

Results

No cost of surveillance for R alleles relative to S alleles of Rps2

To test for surveillance costs of Rps2 alleles, we measured the lifetime fitness of three resistant (Rps2R) and one partially resistant (Rps2pR) isolines relative to one susceptible (Rps2S) allele at each of three genomic insertion sites in a field experiment performed in the absence of pathogens carrying avrRpt2 (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1). After correction for multiple testing, there were no significant differences in the fitness proxies of isogenic plants carrying Rps2pR and Rps2S alleles at the same insertion site (Supplementary Tables 2-4). Significant differences in correlations between fitness proxies might reveal differential resource allocation across resistance classes; however, such differences in fitness proxy correlations were not evident between Rps2R, Rps2S, and Rps2pR lines after a multiple testing correction (Fisher's z test, NS). Two fitness proxies supported higher, rather than lower, fitness for Rps2R alleles than Rps2S alleles (Supplementary Table 3). At the anti-conservative 5% level, there was no consistency in the fitness benefit of susceptible, resistant or partially resistant alleles when integrated into the same genomic location (Supplementary Tables 2-4). Additionally, there was considerable variation in the fitness associated with particular susceptible or resistant alleles across insertion sites (Figure 2a-c).

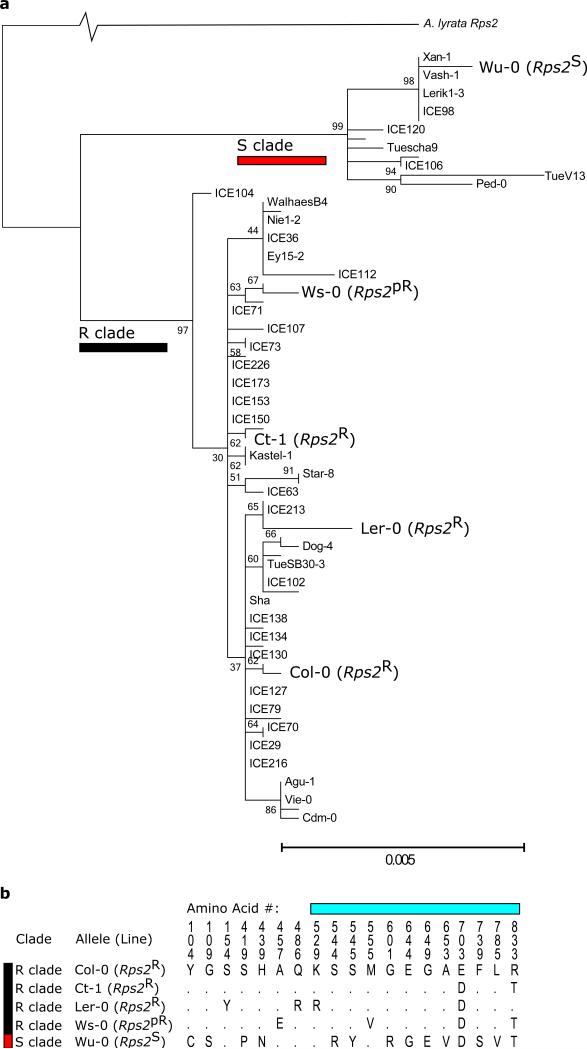

Figure 1.

Natural variation in Rps2 captured by the transgenic allelic series. Red and black bars indicate the susceptible and resistant clades of Rps2 alleles, respectively. a) The two clades of Rps2 alleles were inferred from the coding sequence of Rps2 using maximum likelihood, and included 80 genomes from Cao et al.37 and Sanger sequencing of the five alleles used in this study. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together out of 1000 bootstrap replicates is shown next to the branches. b) Amino acid variation in the alleles used in this study. Cyan bar indicates the Leucine-rich repeat region of Rps2; Rps2R and Rps2pR lines are resistant and partially resistant to Pseudomonas syringae pv. avrRpt2.

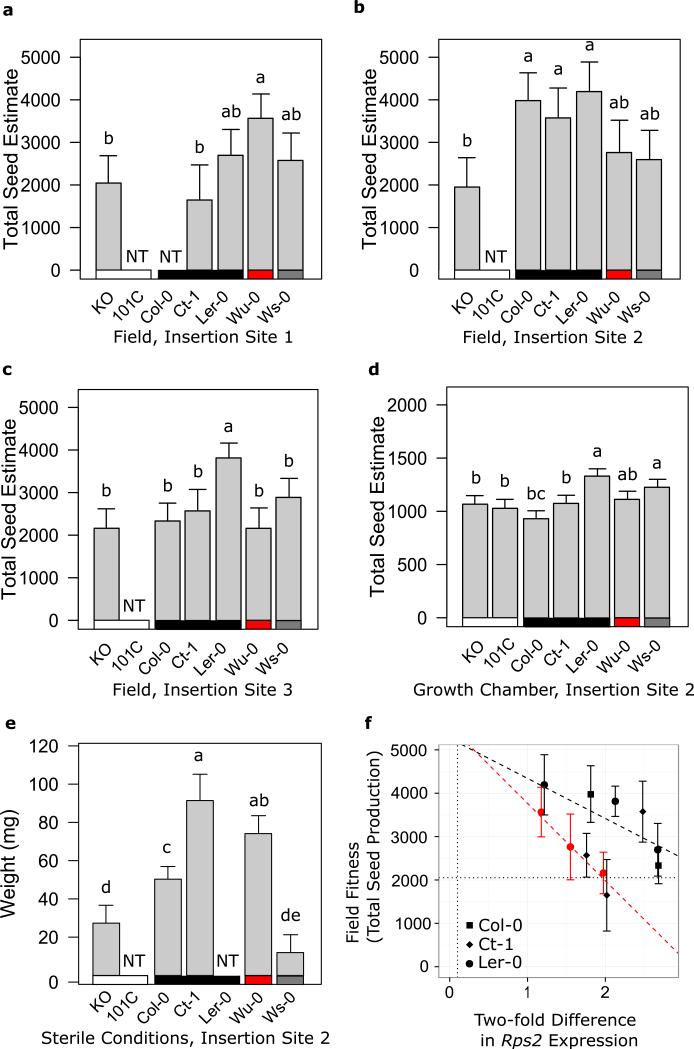

Figure 2.

Significant fitness variation among lines in the allelic series in the absence of pathogen. KO is the rps2-101C mutant with empty lox sites at the insertion site for that line, referred to in the text as the Rps2KO line; 101C is the Rps2 null mutant without an inserted lox site. Lines with Rps2 inserted at three genomic locations, or insertion sites, were tested. Black bar is under Rps2R lines, grey bar is under Rps2pR lines, red bar is under Rps2S lines, and white bar is under Rps2KO lines. Letters above bars within each insertion site indicate grouping using Tukey's post-hoc test. Lines with “NT” were not grown in this experiment. (a-c) Field fitness results. a) Field fitness for insertion site one. The isoline with the Col-0 allele at insertion site one did not germinate. b) Field fitness for insertion site two. c) Field fitness for insertion site three. d) Growth chamber fitness for insertion site two. e) Sterile condition fitness for insertion site two. The isoline with the Ler-0 allele did not germinate in this experiment. f) Average Rps2 expression at three weeks is negatively correlated with fitness in the field. The x-axis shows unitless relative expression of the isogenic lines (points) and the native accessions (vertical dotted line). Black and red dashed lines are the regression lines for the R and S clades, respectively, for the relationship between fitness and expression nested in allelic class. Black points are Rps2R lines from the resistant clade of Rps2, and red points are Rps2S lines from the susceptible clade of Rps2. The average fitness of the Rps2 knockouts is plotted at the horizontal dotted line.

Expression levels can alter the penetrance of phenotypes19, and overexpression of Rps2 can lead to nonspecific activation of the hypersensitive response (HR), or even lethality, if expression levels are too high20,21. The expression of each allele varied within and across insertion sites when transgenic plants were measured in growth chamber conditions (Supplementary Figure 2), and in many cases Rps2 expression was two- to four-fold higher in the isolines than in the accessions from which the alleles derived (Supplementary Figure 3). To investigate the relationship between fitness variation and Rps2 expression, we modeled lifetime seed production in the field as a linear function of average Rps2 expression at 23 days for each allele nested within allele class (Figure 2f; Supplementary Table 5). We also included as a covariate the date at which each plant was collected from the field. For both the Rps2R and Rps2S classes, basal expression of Rps2 was negatively correlated with lifetime fitness (Figure 2f; F = 9.666; df = 8, 602; R2 = 0.114, p values = 0.0028, 0.024), although the negative correlation for the Rps2pR class was not significant (p value = 0.73). These results indicate that Rps2 overexpression is costly in the absence of pathogens for both R and S clade alleles. Adding Rps2 expression into the fitness model did not reveal differences in performance that were masked by differences in expression between Rps2R, Rps2pR, and Rps2S lines (Supplementary Table 5).

An artificial Rps2 knockout is significantly less fit in the absence of pathogens

If resistant and susceptible alleles have equivalent fitness in the absence of pathogens, then the benefit of Rps2R resistance should have driven the Rps2R clade to fixation. However, both clades have been maintained for millions of years in A. thaliana16. We hypothesized that Rps2S, and perhaps Rps2R, alleles must have another beneficial function to permit maintenance of the Rps2S clade. To explore this possibility, we compared the fitness of all lines with an expressed allele of Rps2 (collectively, Rps2+) to three artificial knockout isolines (Rps2KO), using the same field experiment performed in the absence of pathogens carrying avrRpt2. In 19 out of 21 comparisons using seven fitness proxies for alleles at each of the three insertion sites, Rps2+ isolines demonstrated higher performance than Rps2KO isolines, although after correction for multiple testing, only five of these instances were significant (Supplementary Tables 6-8). In terms of lifetime seed set, Rps2KO individuals suffered up to a 54% reduction relative to Rps2+ isolines (Figure 2a-c); this fitness cost was significant for the five lines with the lowest Rps2 expression. This pattern follows from the negative correlation between basal Rps2 expression and lifetime fitness in both Rps2R and Rps2S allele classes (Figure 2f), such that highly expressing A. thaliana lines suffered a fitness reduction much like that observed in the knockout lines. Interestingly, the comparisons revealing a significant cost of the Rps2 knockout include Rps2+ lines with expression levels most similar to native accessions (Supplemental Figure 3; Figure 2f). Rps2KO individuals also had a significantly weaker correlation between plant weight and total collected seed (Fisher's z test p = 4.8E-06) than plants with any other allele of Rps2 (correlation coefficient of 0.85 compared to all > 0.93); this pattern was driven by a number of Rps2KO plants with much lower seed sets than expected for their weight. Taken together, these results suggest that low expression of any allele of Rps2 is beneficial in the absence of known Rps2-mediated pathogens carrying avrRpt2.

We considered two hypotheses to explain the observed benefit of all Rps2 alleles in the absence of P. syringae pv. avrRpt2. First, the presence of a different, and undetected, pathogen recognized by all alleles of Rps2 in the field may have provided a benefit to isolines carrying alleles susceptible to avrRpt2. Alternatively, a pleiotropic function for Rps2 in the absence of disease may have contributed to its benefit. To discriminate between these hypotheses, we first repeated our fitness experiment in a growth chamber that mimicked the stressful environmental conditions of our field environment but was known to be free of RPS2-recognized pathogens. Due to size constraints of the growth chamber, we used isolines from only one insertion site in this experiment. As in the field experiment, after correction for multiple testing, there were no significant differences in fitness proxies between Rps2R or Rps2pR lines relative to Rps2S lines (Figure 2d; Supplementary Table 9; F = 9.20, df = 9, 1009, p value > 0.003). Again, Rps2+ lines set significantly more seed than Rps2KO lines (Supplementary Table 10; F = 39.8, df = 2, 875, p value = 0.006). Thus, the growth chamber results recapitulated the results seen in the field.

As a final confirmation that the observed fitness difference was not due to an interaction with an unknown microbe, we grew our isolines from one insertion site in sterile conditions on agar. Again, Rps2+ plants had a higher weight than Rps2KO plants at 21 days (Figure 2e, F = 9.63, df = 1, 114, p value = 0.0024). This result excluded the possibility that the presence of Rps2 carried a fitness benefit due to recognition of pathogens.

Our isolines were all created using a Cre-lox system in the rps2-101C mutant background. It should be noted that, though this background is often used as an Rps2 null7,20-27, it nonetheless produces a 235 amino acid, N’ terminal fragment of an RPS2 protein which contains the entirety of the RPS2 coiled-coil domain. In addition, our constructs could have anti-sense transcription of RPS2, as is seen for the native copy of RPS2, or ectopic expression of the last three exons of At4g26100. Though previous work has demonstrated that truncation mutants of RPS2 are not autoactive21,28 and do not interact with typical RPS2-interacting proteins21, we sought to test that this truncated RPS2-101c protein, anti-sense transcript and/or the presence of nptII and lox sites did not contribute to plant performance. To do this, we compared the fitness of a transgenic Rps2KO line, created in the rps2-101C background and containing lox sites at insertion site two, with an independently created Col-0 amiRNA knockdown of Rps2 grown under sterile conditions (Supplementary Figure 4). There were no significant differences in weight between these two susceptible lines (p value > 0.65). We additionally failed to detect a difference in the weight of two resistant lines, Col-0 and a transgenic Rps2KO line with the Col-0 allele at insertion site two (p value > 0.45). Thus, neither the rps2-101C background and its associated truncated RPS2 protein, or the lox sites and nptII, impact plant performance directly or through an interaction with Rps2. Furthermore, both Rps2+ plant genotypes had significantly higher weight than both genotypes without Rps2 (p value < 0.0005) when grown under sterile conditions. A comparison of Rps2 isolines not created in the rps2-101C background confirmed the growth benefit of Rps2: the Col-0 amiRNA knockdown line was significantly less fit than Col-0 (p value = 0.0026). Thus, removal of RPS2 protein is associated with reduced performance both in the rps2-101C and Col-0 backgrounds. In combination, these results demonstrate a beneficial pleiotropic function of Rps2 measurable in stressful abiotic environments in the absence of pathogen.

Rps2-associated changes in defense response gene expression in the absence of pathogen

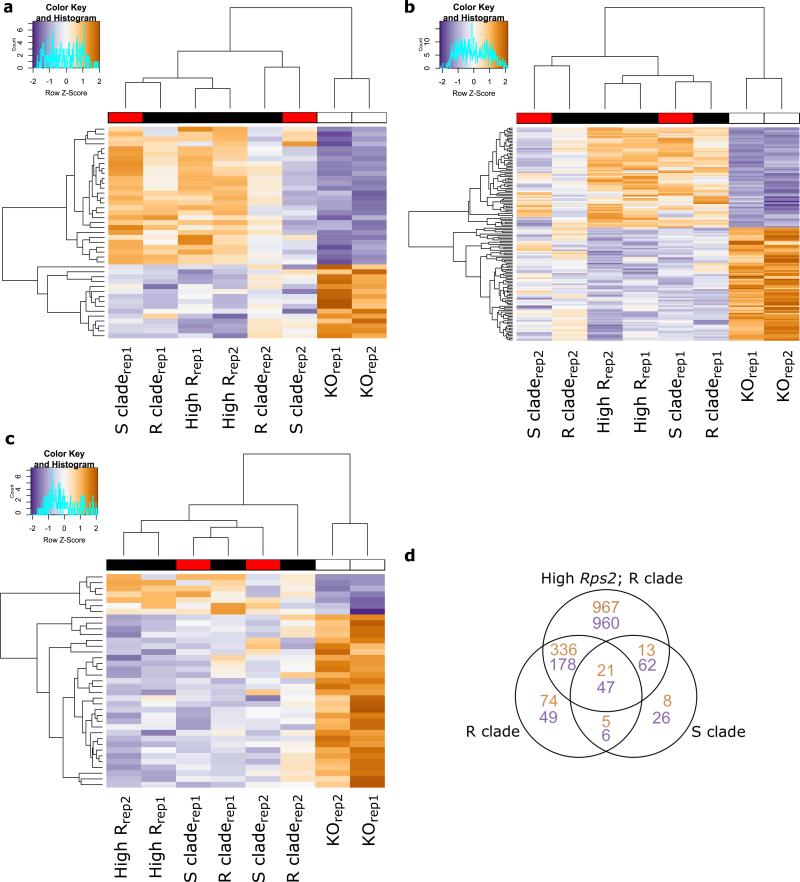

To investigate novel functions of Rps2 in the absence of pathogens, we determined the expression profile of two Rps2R, one Rps2S, and one Rps2KO line grown in sterile conditions. We first contrasted the expression profiles of an Rps2R and Rps2S line that shared the same insertion site and exhibited similar expression levels. In the absence of pathogens, the difference between R and S alleles with similar expression levels was minimal (Supplementary Figure 5). The Rps2R line had 14 genes that were upregulated and two genes that were downregulated relative to the Rps2S line (Supplementary Figure 5). These genes were enriched for gene ontology (GO) annotations of response to stress, particularly for response to water stress (Supplementary Table 11; p value = 1.24E-05). The field fitness data displayed two patterns that we further explored with transcriptome data. First, we observed that Rps2 knockout lines had lower lifetime fitness than Rps2+ lines, essentially irrespective of Rps2 expression level (Figure 2f). Second, given Rps2 presence, there was an inverse relationship between Rps2 expression level and fitness (Figure 2f). We explored the first of these two patterns, of Rps2 presence or absence, by determining the expression profiles of three Rps2+ lines and contrasting them with the Rps2KO line. Rps2+ lines upregulated 538 genes relative to Rps2KO lines, and downregulated 312 genes. Genes upregulated in Rps2+ plants were enriched for GO annotations involving photosynthesis and light response (Figure 3a; Supplementary Table 12; p values = 2.47E-03, 3.91E-05), while genes downregulated in Rps2+ plants were enriched for stimulus response, stress response, biotic stimulus response, and defense response annotations (Figure 3b,c; Supplementary Table 13; p values = 1.18E-16, 3.57E-16, 7.41E-11, 9.01E-11). We found substantial overlap in genes differentially expressed in independent contrasts of single Rps2+ lines and the Rps2KO line (Figure 3d); genes identified in each single-line comparison were consistently enriched for the same GO annotations (Figure 3d; Supplementary Tables 14-19). Thus, removing both R and S alleles of Rps2 from A. thaliana predominantly increased expression of genes that are induced in response to stress and pathogens.

Figure 3.

Rps2 knockout lines differentially express stress response, defense response, and growth related genes relative to all lines with an allele of Rps2. R clade and S clade are resistant and susceptible Rps2 lines, Col-0 and Wu-0, with similar levels of expression from insertion site two, and high R is the Col-0 allele of Rps2 from insertion site three, which has a higher level of Rps2 expression. (a-c) Heatmaps and dendrograms of gene sets as described below. Genes are in rows, and biological replicates are in columns, with both dendrograms grouped by similarity of expression in the gene set displayed. KO is the rps2-101C mutant with empty lox sites at the insertion site two. a) Differentially expressed genes with GO annotations related to photosynthesis or response to light stimulus. b) Differentially expressed genes with GO annotations of response to stimulus or response to stress. c) Differentially expressed genes with GO annotations of defense response or response to biotic stimulus. d) The overlap of differentially expressed genes for three contrasts of lines with an Rps2 allele and the knockout. Orange values are upregulated and blue are downregulated relative to the knockout.

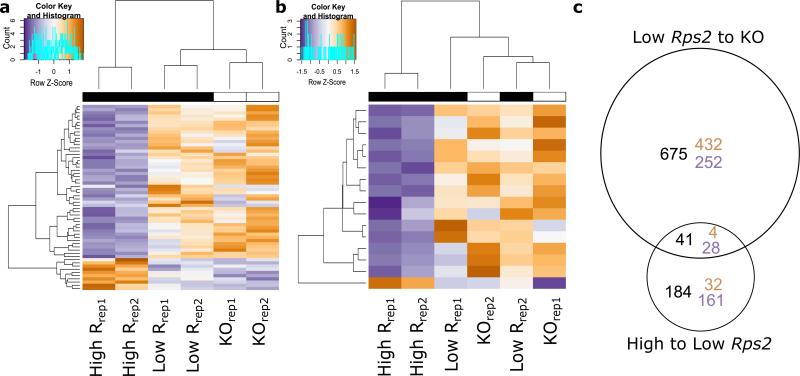

We explored the second of these two patterns, Rps2 expression level, by comparing the expression profiles of two Col-0 Rps2R lines with high and low Rps2 expression under sterile conditions. Expression of 36 genes was upregulated in the high Rps2 expression line relative to the low Rps2 expression line, and expression of 189 genes was downregulated (Figure 4a). Upregulated genes in the high Rps2 expression line were enriched for genes involved in response to stimulus, particularly for thalianol metabolic processes (Figure 4a; Supplementary Table 20; p value = 1.05E-05). Downregulated genes in the high Rps2 expression line were enriched for response to stimuli and stress, particularly for response to biotic stimulus and for the defense response (Figure 4a,b; Supplementary Table 21; p values = 3.38E-10, 1.75E-08, 1.67E-03, 4.03E-04). In contrast to the previous comparison between Rps2+ and Rps2KO, defense related genes were enriched in the downregulated gene set in the line with lower field fitness, or the line with higher Rps2 expression level, rather than upregulated as in the Rps2 knockout. The set of downregulated genes contained a subset that was differentially expressed in only the high Rps2 expression line; this gene subset was also enriched for GO categories of response to stress and the defense response (Figure 4c; Supplementary Table 22; p values = 1.04E-02; 1.28E-02). Rps2 overexpression therefore downregulated an additional, unique set of defense response genes than those induced in Rps2 null mutants (Figure 4b,c). Thus, we observe enrichment for defense related genes that distinguish the highly fecund, low Rps2 expression line from both the Rps2 knockout and high Rps2 expression lines, although the genes that contribute to these enrichments are different.

Figure 4.

Rps2 expression level affects both stress response and defense response genes. (a,b) Heatmaps and dendrograms of gene sets as described below. Genes are in rows, and biological replicates are in columns, with both dendrograms grouped by similarity of expression in the gene set displayed. KO is the rps2-101C mutant with empty lox sites at the insertion site two, low R is the Col-0 allele with a low level of expression from insertion site two, and high R is the Col-0 allele from insertion site three, which has a higher level of basal Rps2 expression. a) Differentially expressed genes with GO annotations of response to stimulus or response to stress. b) Differentially expressed genes with GO annotations of defense response or response to biotic stimulus. c) The proportional overlap of genes differentially expressed between low and high Rps2 expression lines with genes differentially expressed between the low expression line and the knockout. Orange values are upregulated and blue are downregulated relative to the knockout.

Discussion

Costs of resistance contribute to the long-term maintenance of polymorphism at defense genes because they help explain the persistence of susceptible alleles. However, it is hard to understand why the production of minute quantities of a recognition protein, such as those produced by R-gene loci, would entail a large physiological cost. It was therefore surprising that our emerging picture of the costs associated with R-gene loci is that they are large – on the order of 10%8,9. Here, we report on the absence of a cost associated with Rps2, an R-gene that segregates for the maintenance of alternative alleles16. This result makes sense in that both R and S alleles are expressed in our Rps2 isolines; thus, the difference between R and S genotypes is small relative to the difference in isolines segregating for indel polymorphisms, as in the previous R-genes for which costs have been measured8,9. Since a large fraction of R-genes in the genome harbor multiple alleles29,30, our results help explain how host genomes can tolerate the genetic load associated with R-gene resistance. We suggest that while stable indel polymorphisms may be maintained by large costs of resistance, stable non-indel R-gene polymorphisms are more likely to be maintained by a variety of ecological and physiological mechanisms, as elaborated below. Thus, this work reveals a fundamental effect of genetic architecture on the manifestation of costs of resistance.

Our creation of an artificial indel polymorphism for Rps2 revealed a fitness benefit of up to 40% associated with the presence of Rps2, albeit an equivalent benefit for R and S alleles (Figure 2). The benefit of carrying an allele of Rps2 appears to result from its function as a negative regulator of the defense response – loss of Rps2 causes the upregulation of a number of genes involved in induced responses to stress (Figure 3; Supplementary Table 13). The critical function of Rps2 provides a clear explanation for why S alleles are not deleted, as they typically are for Rpm1 and Rps5; however, it does not explain the maintenance of both R and S alleles at Rps2. There are several possible explanations for the long-term maintenance of these clades. First, the S alleles may encode the ability to recognize effectors or pathogens that have yet to be identified, leading to selection for the retention of the functional “S” allele. Alternatively, the previously measured cost of attack7, in which the cost of response by R alleles of Rps2 is a larger physiological burden than infection, may favor S alleles in certain environments. Such a benefit of susceptibility, even though environmentally restricted, could promote stable Rps2 polymorphism4. Spatial or temporal variation in other costs of resistance, namely in costs of surveillance or defense, could also promote stable Rps2 polymorphism4,6. Finally, spatial or temporal variation in costs of virulence in pathogens carrying avrRpt2 could similarly promote stable polymorphism at Rps24,31.

More generally, functional R-gene alleles, when expressed, have the potential to carry a physiological cost due to expression or mis-expression20,21. For Rps2, we observed a cost associated with increasing levels of expression (Figure 2f). Selection should act to minimize the costs associated with R-loci, especially costs of S alleles that have no pleiotropic, beneficial function. We suggest that a natural consequence of this selective process should be the deletion of S alleles, because deletions can carry no costs associated with their (mis)expression. Indeed, only when S alleles harbor beneficial effects should they be retained by selection, as is the case for Rps2. Our results thus demonstrate that defense loci segregating for functional alternatives, rather than for indel polymorphisms, limit the manifestation of costs of surveillance. Furthermore, our results suggest that genetic architecture both impacts, and is impacted by, physiological costs associated with segregating R-gene alleles. Given the substantial variation in R-gene evolutionary histories2 and genetic architectures13,29,32, it will be fascinating to further disentangle the complex interplay of genetic, physiological and ecological factors in the generation of diversity.

Methods

Cre-lox Insertion of RPS2

We introduced five intact alleles of Rps2 into the same genomic location using a Cre-lox system in an rps2-101C mutant of Col-033, a plant line with a stop codon in RPS2 at amino acid 235 that is a presumed null mutation15 (Supplementary Figure 1). We also introduced an empty integration vector, without Rps2, to obtain empty vector insertions in the isogenic RPS2 null background (hereafter Rps2KO). We repeated this process for each of three genomic locations, creating 18 isolines in all (Supplementary Table 1). Three alleles from the resistant clade, Col-0, Ct-0, and Ler-0 (R clade alleles or Rps2R lines) were characterized as resistant in their native genetic background16,34. One allele from the R clade, Ws-0 (Rps2pR), was characterized as partially resistant in its native genetic background34. One allele from the susceptible clade, Wu-0 (S clade allele or Rps2S lines) was characterized as susceptible in its native genetic background14. The Rps2R and Rps2pR lines exhibited elevated HR and resistance compared to the Rps2S and Rps2KO lines upon infection with P. syringae pv. avrRpt235 (Supplementary Figures 6-7). Further details are included in the supplementary methods.

Field Fitness Experiment

Seedlings of each of 17 RPS2 lines were germinated in 98-cell trays containing 50:50 Metromix 200: Farfad C2 in the University of Chicago greenhouse. Plants with the Col-0 allele at insertion site one did not germinate. Seedlings were thinned on day seven of growth and flat locations were randomly cycled daily in the greenhouse to standardize growth conditions. On day 14, 100 seedlings per line were transplanted to a tilled field site in Downers Grove, Illinois, in a randomized block design in which each block contained a plant from each Rps2 line. Plants were set out in 15 rows of nine blocks, spaced by 0.25m within rows and by 1m between rows. Plants were irrigated for one week to reduce transplantation shock, and then sustained only by natural rainfall. The field was hand weeded once and plants received no other protection from competition or pests. 55% of plants died; the majority of these died in the first week presumably due to transplantation shock. Plant survival was evenly distributed among the allele types. Seven fitness proxies were measured: dry weight, undehisced seed set, seed size, silique number, average seeds per silique, and numbers of aerial and basal branches. Total seed set was estimated by multiplying silique number by the average number of seeds per silique.

Sampling for Pathogen Presence

96 plant samples representing all 17 lines were destructively harvested from the field on days 30 and 40 of growth. P. syringae was present in the majority of the plant samples, while avrRpt2 was not seen in any sample. Sampling details are described in the supplementary methods.

Growth Chamber Fitness Experiment

1400 seedlings of seven lines with Rps2 at insertion site two were germinated in 36-cell trays containing 25:25:50 Metromix 200:Farfad C2:Turfase in the University of Chicago growth chambers. Due to growth chamber size constraints, only lines from insertion site two were included. Seedlings were thinned and accessions were randomized within flats on day 7 of growth. After day 14, plants were watered every other day to mimic stressful growth conditions in the field. After six weeks of growth, we stopped watering and allowed the plants to dry for two weeks before processing. Two fitness proxies were measured: dry weight and undehisced seed set.

Sterile Plant Fitness Experiments

Two sets of lines were grown in sterile conditions. First, isogenic lines with Rps2 at insertion site two were grown to measure fitness of plants with alleles of Rps2 relative to the Rps2 knockout. Second, four lines were measured to determine whether the truncated RPS2 protein present in the rps2-101C impacted the surveillance cost of Rps2 resistance: Col-0, an amiRNA knockdown of RPS2 in a Col-0 background, and two lines on an isogenic rps2-101CRps2 null background at insertion site two, one containing an insert of the Col-0 allele and one containing only the empty lox cassette. Further information on sterile conditions is included in the supplementary methods.

Fitness Analysis

R was used to specify nested linear models using the lm function from the stats package. Two sets of linear models were used to generate confidence intervals for each of seven fitness proxies at each insertion site for the field data, and for two fitness proxies for the growth chamber data. The field linear models included an effect of the date the plant was collected from the field. The growth chamber linear models included an effect of the date the plant was processed. The first set of models nested allele into either one of three (S, R, pR) or one of two (KO, Rps2+) allelic classes and considered each genomic insertion site independently. The second set of models combined data for all genomic insertion sites to nest Rps2 expression level into one of three allele classes (S, R, pR).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Expression of all Rps2 isogenic lines was measured with qPCR using primers for Rps2 and normalizing between samples using three reference genes: PP2A, Helicase, and bHLH36. A subset of isogenic lines was used to compare Rps2 expression in natural accessions to expression in the allelic series. Details of qPCR are described in the supplementary methods.

Whole Transcriptome Profiling

Plants with the Col-0 allele at insertion site two (R), the Col-0 allele at insertion site three (High R), the Wu-0 allele at insertion site two (S) or an empty vector at insertion site two (KO) were grown in sterile growth media as in the sterile plant fitness experiments. The Col-0 allele was chosen as the representative R allele for two reasons: 1) non-coding divergence was smallest between Col-0 and Wu-0 (Supplementary Figure 1b) and 2) Rps2 gene expression variation existed to allow observation of expression level effects. Specific contrasts included: 1) R vs S; 2) R, 3) High R, and 4) S vs KO; and 5) High R vs R. RNA-seq and analysis followed standard protocols described in the supplementary methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Heather King, Laura Merwin, Chris Meyer, Wayan Muliyati, Aaron Olsen, Nadia Shakoor, and Tom Stewart for their assistance in the field; Jean Greenberg for donation of strains for infection; Paul Hooykaas for pSDM3110, Madlen Vetter for her high-throughput infection protocol; and Ben Brachi, Talia Karasov, Martin Kreitman, and Laura Merwin for helpful discussions. This research was supported by NSF and NIH grants to J.B. and a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China to XQS (Grant no.: 31470448).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

XQS created the allelic series; AM, XQS, and JB designed the experiments; AM conducted the experiments, JB conceived of the experiments, AM and JB wrote the paper.

The authors declare they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Tian D, Araki H, Stahl E, Bergelson J, Kreitman M. Signature of balancing selection in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:11525–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172203599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakker E, Toomajian C, Kreitman M, Bergelson J. A Genome-Wide Survey of R Gene Polymorphisms in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Online. 2006;18:1803–1818. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.042614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thrall P, et al. Rapid genetic change underpins antagonistic coevolution in a natural host-pathogen metapopulation. Ecol Lett. 2012;15:425–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown J, Tellier A. Plant-Parasite Coevolution: Bridging the Gap between Genetics and Ecology. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2011;49:345–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-072910-095301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown JK. Durable resistance of crops to disease: a Darwinian perspective. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2015;53:513–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-102313-045914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreno-Gámez S, Stephan W, Tellier A. Effect of disease prevalence and spatial heterogeneity on polymorphism maintenance in host–parasite interactions. Plant Pathol. 2013;62:133–141. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korves T, Bergelson J. A novel cost of R gene resistance in the presence of disease. Am. Nat. 2004;163:489–504. doi: 10.1086/382552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tian D, Traw MB, Chen JQ, Kreitman M, Bergelson J. Fitness costs of R-gene-mediated resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2003;423:74–7. doi: 10.1038/nature01588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karasov T, et al. The long-term maintenance of a resistance polymorphism through diffuse interactions. Nature. 2014;512:436–440. doi: 10.1038/nature13439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant M, et al. Structure of the Arabidopsis RPM1 gene enabling dual specificity disease resistance. Science 11. 1995;269(5225):843–846. doi: 10.1126/science.7638602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stahl EA, Dwyer G, Mauricio R, Kreitman M, Bergelson J. Dynamics of disease resistance polymorphism at the Rpm1 locus of Arabidopsis. Nature. 1999;400:667–71. doi: 10.1038/23260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose L, Atwell S, Grant M, Holub E. Parallel Loss-of-Function at the RPM1 Bacterial Resistance Locus in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front Plant Sci. 2012;3:287. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyers BC, Kozik A, Griego A, Kuang H, Michelmore RW. Genome-wide analysis of NBS-LRR-encoding genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2003;15:809–34. doi: 10.1105/tpc.009308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kunkel B, Bent A, Dahlbeck D, Innes R, Staskawicz B. RPS2, an Arabidopsis Disease Resistance Locus Specifying Recognition of Pseudomonas syringae Strains Expressing the Avirulence Gene avrRpt2. Plant Cell Online. 1993;5:865–875. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.8.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu GL, Katagiri F, Ausubel F. Arabidopsis mutations at the RPS2 locus result in loss of resistance to Pseudomonas syringae strains expressing the avirulence gene avrRpt2. MPMI. 1993;6(4):434–443. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-6-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mauricio R, et al. Natural selection for polymorphism in the disease resistance gene Rps2 of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2003;163:735–46. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.2.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Out of 300 accessions with sequencing data (see supplemental methods), none have missing data or deletions called for Rps2.

- 18.Bergelson J, Purrington CB. Surveying patterns in the cost of resistance in plants. American Naturalist. 1996;148(3):536–58. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raj A, Rifkin S. Variability in gene expression underlies incomplete penetrance. Nature. 2010;463 doi: 10.1038/nature08781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mindrinos M, Katagiri F, Yu GL, Ausubel FM. The A. thaliana disease resistance gene RPS2 encodes a protein containing a nucleotide-binding site and leucine-rich repeats. Cell. 1994;78:1089–99. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tao Y, Yuan F, Leister RT, Ausubel FM, Katagiri F. Mutational analysis of the Arabidopsis nucleotide binding site-leucine-rich repeat resistance gene RPS2. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2541–2554. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.12.2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNellis TW, Mudgett MB, Li K, Aoyama T. Glucocorticoid-inducible expression of a bacterial avirulence gene in transgenic Arabidopsis induces hypersensitive cell death. The Plant Journal. 1998;14(2):247–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00106.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leister RT, Katagiri F. A resistance gene product of the nucleotide binding site -- leucine rich repeats class can form a complex with bacterial avirulence proteins in vivo. The Plant Journal. 2000;22:345–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banerjee D, Zhang X, Bent A. The leucine-rich repeat domain can determine effective interaction between RPS2 and other host factors in arabidopsis RPS2-mediated disease resistance. Genetics. 2001;158:439–50. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.1.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Axtell, McNellis, Mudgett, Hsu, Staskawicz Mutational analysis of the Arabidopsis RPS2 disease resistance gene and the corresponding pseudomonas syringae avrRpt2 avirulence gene. MPMI. 2001;14:181–8. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Day B, et al. Molecular Basis for the RIN4 Negative Regulation of RPS2 Disease Resistance. Plant Cell Online. 2005;17:1292–1305. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.030163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Day B, Dahlbeck D, Staskawicz B. NDR1 Interaction with RIN4 Mediates the Differential Activation of Multiple Disease Resistance Pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Online. 2006;18:2782–2791. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.044693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi D, DeYoung B, Innes R. Structure-function analysis of the coiled-coil and leucine-rich repeat domains of the RPS5 disease resistance protein. Plant physiology. 2012;158:1819–32. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.194035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bergelson J, Kreitman M, Stahl EA, Tian D. Evolutionary dynamics of plant R-genes. Science. 2001;292:2281–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1061337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gan X, et al. Multiple reference genomes and transcriptomes for Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2011;477:419–23. doi: 10.1038/nature10414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laine AL, Tellier A. Heterogeneous selection promotes maintenance of polymorphism in host–parasite interactions. Oikos. 2008;117:1281–1288. doi:10.1111/j.0030-1299.2008.16563.x. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo Y-LL, et al. Genome-wide comparison of nucleotide-binding site-leucine-rich repeat-encoding genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:757–69. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.181990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vergunst AC, Jansen LE, Hooykaas PJ. Site-specific integration of Agrobacterium T-DNA in Arabidopsis thaliana mediated by Cre recombinase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2729–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.11.2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caicedo AL, Schaal BA, Kunkel BN. Diversity and molecular evolution of the RPS2 resistance gene in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:302–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guttman DS, Greenberg JT. Functional analysis of the type III effectors AvrRpt2 and AvrRpm1 of Pseudomonas syringae with the use of a single-copy genomic integration system. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2001;14:145–55. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Czechowski T, Stitt M, Altmann T, Udvardi MK, Scheible W-RR. Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:5–17. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.063743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao J, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of multiple Arabidopsis thaliana populations. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:956–63. doi: 10.1038/ng.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.