Abstract

Carotid bodies are the principal peripheral chemoreceptors for detecting changes in arterial blood oxygen levels, and the resulting chemo-reflex is a potent regulator of the sympathetic tone, blood pressure, and breathing. Sleep apnea is a disease of the respiratory system affecting several million adult humans. Apneas occur during sleep often due to obstruction of the upper airway (obstructive sleep apnea, OSA) or due to defective respiratory rhythm generation by the central nervous system (central sleep apnea). Patients with sleep apnea exhibit several co-morbidities; most notable among them being the heightened sympathetic nerve activity, and hypertension. Emerging evidence suggests that intermittent hypoxia (IH) resulting from periodic apnea stimulates the carotid body and the ensuing chemo-reflex mediates the increased sympathetic tone and hypertension in sleep apnea patients. Rodent models of IH, simulating the O2 saturation profiles encountered during sleep apnea have provided important insights into the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the heightened carotid body chemo-reflex. This article describes how IH affects the carotid body function, and discusses the cellular, molecular and epigenetic mechanisms underlying the exaggerated chemo-reflex.

Keywords: Sensory long-term facilitation, Gaseous transmitters, Oxidative stress, Sympathetic activation, Hypoxia-inducible factors, DNA methylation

INTRODUCTION

This review article is based on 2016 Michael de Burgh Daly Prize Lecture of the Physiological Society. Professor Daly made seminal contributions to the field of autonomic physiology, especially chemo-reflex regulation of cardiovascular function. I am indeed deeply honored to present this lecture, as my own research in the last couple of decades concerns with the regulation of cardio-respiratory functions by carotid body chemo-reflex in experimental models of sleep apnea.

Sleep apnea is a disease of the respiratory system affecting nearly 10% of adult human population (Peppard et al., 2013). Apneas occur during sleep often due to obstruction of the upper airway (obstructive sleep apnea, OSA) or due to defective respiratory rhythm generation by the central nervous system (central sleep apnea). In severely affected patients, the frequency of apneas can be as high as 60 per hour and arterial blood O2 saturations reduce as much as 50% during apneic episodes. Patients with sleep apnea exhibit several co-morbidities most notably a heightened sympathetic nerve activity, and hypertension (Lavie et al., 2000; Nieto et al., 2000; Peppard et al., 2000; Dempsey et al., 2010). In 1980s, Daly suggested that “a potential mechanism exists therefore whereby the peripheral arterial chemoreceptors could contribute to the neurogenic component of hypertension” (de Burgh Daly, 1985). This article presents the emerging evidence showing that heightened carotid body chemo-reflex is a major driver of sympathetic activation and hypertension in patients with sleep apnea and then discusses the cellular and molecular mechanisms mediating the exaggerated chemo-reflex in experimental animal models of sleep apnea.

Carotid body chemo-reflex in sleep apnea patients

Patients with OSA exhibit pronounced increases in sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure during apneic episodes in the night and elevated blood pressure and sympathetic tone during day time, wherein apneas are absent (Peppard et al., 2000; Tamisier et al., 2011). Population based studies showed a clear correlation between the severity of apnea and prevalence of hypertension (Peppard et al., 2000). Obesity is a common co-morbidity in OSA subjects. However, the elevated blood pressures and sympathetic nerve activity are also seen in lean OSA subjects, suggesting that they occur independent of obesity (Narkiewicz & Somers, 1997). OSA patients exhibit elevated circulating and urinary catecholamines (both norepinephrine and epinephrine), which were attributed to increased sympathetic nerve activity (Fletcher et al., 1987; Carlson et al., 1993; Marrone et al., 1993; Somers et al., 1995; Garcia-Rio et al., 2000).

Repetitive apneas lead to periodic hypoxia in the arterial blood. Given that carotid bodies are the major sensory organs for monitoring O2 levels in the arterial blood (Kumar & Prabhakar, 2012), it was proposed that the carotid body chemo-reflex mediates the sympathetic activation in sleep apnea patients (Cistulli & Sullivan, 1994). Consistent with this notion, sleep apnea patients exhibit augmented carotid body chemo-reflex as evidenced by pronounced activation of the sympathetic nerves, increased blood pressure and ventilatory stimulation in response to acute hypoxia (Hedner et al., 1992; Narkiewicz et al., 1999; Kara et al., 2003). Brief hyperoxia, which decreases carotid body sensory nerve activity leads to a greater depression of breathing (Tafil-Klawe et al., 1991; Kara et al., 2003) and blood pressure (Narkiewicz et al., 1999) in sleep apnea patients as compared with control subjects. These studies suggest that exaggerated carotid body chemo-reflex contributes to increased sympathetic nerve activity and hypertension in sleep apnea patients.

Experimental models of sleep apnea

Fletcher and co-workers (Fletcher, 1995) developed a rodent model of intermittent hypoxia (IH) simulating the O2 profiles encountered during sleep apnea. These investigators exposed adult rats to alternating cycles of hypoxia (12s of 3–5% O2) and room air (15–18s), 60 episodes/hour for 6–8 hours during day time, which is the sleep time for rodents. Rats exposed to several days of IH showed hypertension, increased sympathetic nerve activity and elevated urinary catecholamines recapitulating the phenotype reported in sleep apnea patients (Fletcher, 1995). Carotid body chemo-reflex is augmented in IH exposed rodents, as seen by exaggearated sympathetic nerve activity, blood pressure and ventilatory responses to acute hypoxia (Rey et al., 2004; Peng et al., 2006b; Huang et al., 2009). Disrupting the chemo-reflex pathway either by sectioning the carotid sinus nerves (Fletcher et al., 1992; Lesske et al., 1997) or by selective ablation of the carotid body, while preserving the carotid baroreceptor function (Peng et al., 2014b) or by denervating the adrenals, a major sympathetic end organ (Peng et al., 2014b) prevented the development of hypertension and elevated plasma catecholamines in IH treated rodents. The following section describes the effects of IH on major components of the chemo-reflex pathway including the carotid body, brainstem neurons, and the adrenal medulla.

Carotid body (sensor)

IH exposure results in augmented carotid body response to acute hypoxia in rats (Peng & Prabhakar, 2004), mice (Peng et al., 2006b) and cats (Rey et al., 2004). IH also induces a form of carotid body plasticity manifested as sensory long-term facilitation (sensory LTF), which is characterized by long-lasting, progressive increase in baseline sensory nerve activity following repetitive acute hypoxia (Peng et al., 2003). Sensory LTF was observed despite maintaining normal arterial blood gas composition and blood pressure (Peng et al., 2003). The effects of IH on the carotid body were seen after exposure to a minimum of three consecutive days of IH (8 hours per day) but not with a single exposure to IH for 8 hours. The magnitude of the augmented hypoxic sensitivity and sensory LTF increased as the duration of IH extended to 10 days (Peng et al., 2003). Increasing the severity of acute hypoxia used for IH conditioning from 10% to 5% O2 had no noticeable further impact on the magnitude of the carotid body response to acute hypoxia (Peng et al., 2003). These studies suggest that IH leads to remodeling of the carotid body function manifested as sensitization of the hypoxic sensory response and induction of sensory LTF.

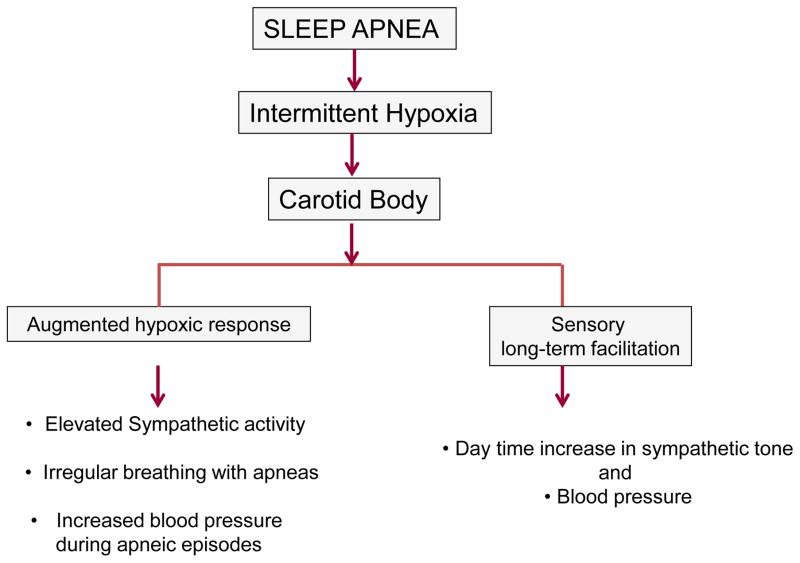

What might be the functional consequences of carotid body remodeling by IH? It was proposed that sensitization of the carotid body response to hypoxia leads to greater sympathetic activation and blood pressures during apneic episodes and the sensory LTF contributes to elevated baseline sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure (Prabhakar, 2013; Fig. 1). Given that enhanced carotid body activity leads to breathing instability with a greater number of apneas (Longobardo et al., 1982), it was further suggested that the augmented carotid body activity might exacerbate the occurrence of apneas (Prabhakar, 2013, Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of intermittent hypoxia associated with sleep apnea on the carotid body sensory nerve activity and its consequences on cardio-respiratory functions.

Brainstem neurons

Sensory information from the carotid body is conveyed to the nucleus tractus solitarius (nTS) and then to the neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), which then translate the carotid body sensory input to changes in sympathetic nerve activity. Kline et al reported increased post-synaptic activity of nTS neurons in IH treated animals (Kline et al., 2007). IH treated rodents also showed an upregulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor 1 (NMDA-R1) and Glutamate receptor 2/3 expressions in the commissural nTS, which receives sensory input from the carotid body (Reeves et al., 2003; Costa-Silva et al., 2012), and augmented AMPA-and NMDA-mediated neuronal excitability (de Paula et al., 2007).

The sympathetic outflow is modulated by the respiratory rhythm (Haselton & Guyenet, 1989; Dempsey et al., 2002), which in turn contributes to neurogenic vasomotor tone (Bachoo & Polosa, 1985). Coupling between the respiratory and sympathetic nerve activities occurs in part, at the RVLM (Dampney, 1994; Guyenet, 2000). The RVLM contains two major groups of pre-sympathetic bulbo-spinal neurons including those expressing adrenaline (C1 group) and non-catecholaminergic neurons (Stornetta et al., 2002). A majority of the bulbo-spinal RVLM pre-sympathetic neurons exhibit respiratory-related activity (McAllen, 1987; Haselton & Guyenet, 1989; Miyawaki et al., 1995). Recently, Moraes, Machado and co-workers (Moraes et al., 2013) reported that a specific population of non-catecholaminergic respiratory-modulated pre-sympathetic neurons in RVLM of IH exposed rats exhibit augmented excitatory synaptic inputs from the respiratory network. The enhanced excitatory synaptic activity of these neurons by IH was due to altered properties of the ion channels in post-inspiratory neurons (Moraes et al., 2015). Collectively, these studies indicate that altered neuronal coupling between the respiratory and pre-sympathetic neurons in the RVLM is an important central mechanism contributing to activation of the sympathetic nervous system by IH.

Adrenal medulla

The adrenal medulla is a major end organ of the sympathetic nervous system which contributes to circulating catecholamines. IH exposed rats exhibit markedly augmented acute hypoxia-induced catecholamine secretion from the adrenal medulla (Kumar et al., 2006).

Are the effects of IH direct or indirect?

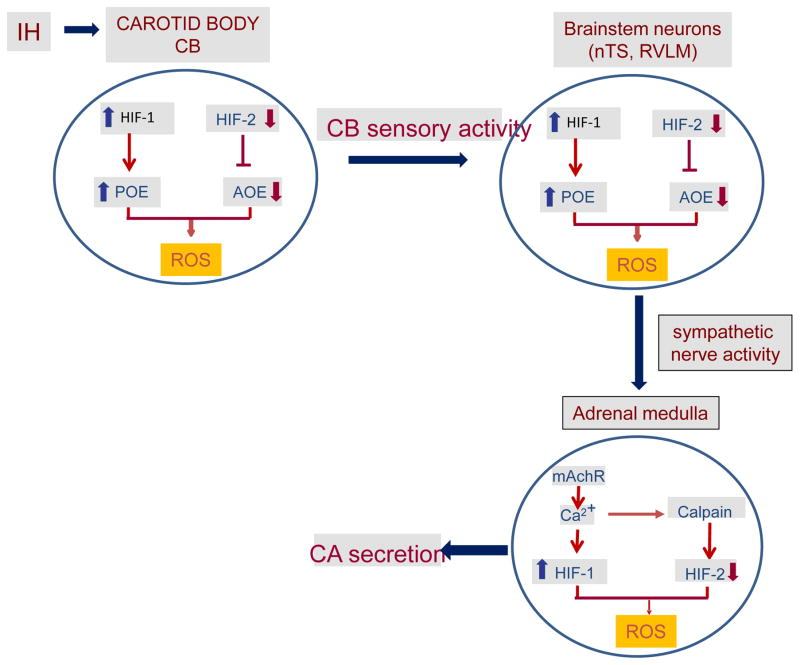

IH produces a modest drop in arterial blood O2 saturation during each episode of hypoxia, which approximates to a reduction in arterial PO2 from ~100 to 80 mmHg i.e., ~20 mmHg reduction (Peng et al., 2014b). This small drop in arterial PO2 is likely to be directly sensed by the carotid body because of its exquisite sensitivity to O2 (Kumar & Prabhakar, 2012) and highest blood flow (de Burgh Daly et al., 1954). On the other hand, this drop in PO2 to ~80 mmHg may not be sufficient to directly affect many central and peripheral tissues, because PO2 of most of these tissues ranges between 30 and 60 mmHg under normoxia (Carreau et al., 2011). However, neural activity is a potent stimulant for eliciting the cellular responses (Fields et al., 2005; Carulli et al., 2011; Ganguly & Poo, 2013). It is conceivable that the effects of IH on tissues such as nTS, RVLM and adrenal medulla are mediated indirectly through enhanced neural input from the carotid body. Consistent with this possibility, selective ablation of the carotid body prevents IH-induced changes in the nTS and RVLM (Peng et al., 2014b). Likewise, the effects of IH on adrenal medulla could be blocked either by carotid body ablation or by sympathetic denervation (Peng et al., 2014b). A recent study (Moraes et al., 2015) also reported that carotid body neural input is required for IH-induced changes on ion channel properties of post-inspiratory neurons. Collectively, these findings suggest that IH directly affects the carotid body function, whereas the effects of IH on brainstem neurons and the adrenal medulla are indirect, and mediated by sensory input from the carotid body (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Direct and indirect effects of intermittent hypoxia (IH) on the chemo-reflex pathway including the carotid body (the sensor), neurons of nucleus of the tractus solitarious (nTS) and rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) and adrenal medulla (sympathetic end organ). HIF-1 and HIF-2= Hypoxia-inducible factors 1 and 2, POE= pro-oxidant enzymes, AOE= anti-oxidant enzymes, ROS= reactive oxygen species, mAChR= muscarinic acetylcholine receptor, CA secretion= catecholamine secretion, CSN= carotid sinus nerve.

Cellular mechanisms underlying chemo-reflex activation by IH

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) were proposed to mediate the exaggerated carotid body chemo-reflex by IH (Prabhakar, 2001; Yuan et al., 2004). Supporting this possibility, rodents exposed to IH showed elevated ROS levels in the three major components of the chemo-reflex pathway including the carotid body (Peng et al., 2003; Peng et al., 2014b), nTS and RVLM (Zhan et al., 2005; Peng et al., 2014b), and adrenal medulla (Kumar et al., 2006; Peng et al., 2014b).

Multiple sources contribute to IH-induced increase in ROS. These include: a) NADPH-oxidase-2 (Nox2) (Zhan et al., 2005; Peng et al., 2009; Lam et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2014b), b) Xanthine oxidoreductase (XO) (Nanduri et al., 2013), and c) inhibition of mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) at the complex I (Peng et al., 2003; Yuan et al., 2004), which is known to increase ROS generation (Ambrosio et al., 1993). The inhibitory effects of IH on mitochondrial complex I are indirect and require ROS generated by Nox2 (Khan et al., 2011). Cellular ROS levels also depend on their rate of degradation by anti-oxidant enzymes. IH decreases the enzyme activity of superoxide dismutase 2 (Sod-2), a major anti-oxidant enzyme in the carotid body (Nanduri et al., 2009b), nTS, RVLM and adrenal medulla (Peng et al., 2014b). These studies suggest that elevated ROS generation by IH in the chemo-reflex pathway is due to increased activity of pro-oxidant enzymes and decreased activity of anti-oxidant enzymes (Fig. 2).

The importance of ROS signaling was assessed by treating IH exposed rats with anti-oxidants. Anti-oxidant treatment during IH exposure prevented the elevated ROS levels, blocked the exaggerated carotid body activity, enhanced adrenal medullary catecholamine secretion, elevated plasma catecholamine levels, and hypertension (Peng et al., 2003; Peng & Prabhakar, 2004; Peng et al., 2006b; Peng et al., 2014b). In contrast, a single application of anti-oxidant on the last day of IH treatment was found to be ineffective in preventing the carotid body hypersensitivity to hypoxia (Peng et al., 2003), suggesting that ROS-mediated signaling cascade rather than ROS generation per se is critical for evoking heightened chemo-reflex by IH.

Molecular determinants of ROS generation by IH

The effects of IH on ROS levels develop over time and require transcriptional regulation of genes encoding the pro-and anti-oxidant enzymes (Pawar et al., 2008; Nanduri et al., 2009a; Peng et al., 2009). Recent studies showed that the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) family of transcriptional activators is critical for IH-induced ROS generation. HIF-1 and HIF-2 are the two best studied members of the HIF family, which are heterodimers, comprised of an O2-regulated α subunits and a constitutively expressed HIF-1β subunit (Prabhakar & Semenza, 2012).

IH increases HIF-1α protein in the carotid body, nTS and RVLM as well as adrenal medulla (Peng et al., 2014b). The increased HIF-1α protein expression by IH requires Ca2+-dependent activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and the ensuing increase in protein synthesis by the mammalian-target of rapamycin (mTOR) (Yuan et al., 2008). Blockade of HIF-1α activation either by pharmacological or by genetic approaches completely abolishes IH-induced increase in ROS generation (Yuan et al., 2011). Further studies revealed that HIF-1 mediates the transcriptional activation of Nox2, a major pro-oxidant enzyme by IH (Yuan et al., 2011). Mice with heterozygous deficiency of HIF-1α exhibit remarkable absence of IH-induced increase in ROS, activation of the carotid body, hypertension and elevated plasma catecholamines (Peng et al., 2006b).

HIF-2α (also known as endothelial PAS domain protein-1, EPAS-1) shares ~50% sequence homology to HIF-1α and also interacts with HIF-1β (Ema et al., 1997; Tian et al., 1997). In striking contrast to HIF-1α, IH decreases HIF-2α protein in the carotid body, adrenal medulla (Nanduri et al., 2009b) and in nTS and RVLM (Peng et al., 2014b). The HIF-2α protein degradation by IH is mediated by Ca2+-dependent protease, calpain (Nanduri et al., 2009b). The reduced HIF-2α expression by IH results in transcriptional down regulation of mRNAs encoding several anti-oxidant enzymes including the Sod-2 in the carotid bodies (Nanduri et al., 2009b). Mice partially deficient in HIF-2α display several phenotypic characteristics of IH exposed mice including the augmented hypoxic sensitivity of the carotid body, elevated blood pressures, increased plasma catecholamines, disrupted breathing with apneas, and oxidative stress and all these effects were blocked by anti-oxidant treatment (Peng et al., 2011a).

The above described studies suggest that an imbalance between HIF-1 and HIF-2 and the resulting alteration in transcriptional regulation of pro-oxidant (e.g., Nox2) and anti-oxidant enzymes (e.g., Sod-2) is a major molecular mechanism underlying increased ROS generation in the chemo-reflex pathway by IH. IH-evoked imbalance in HIFα isoforms and the ensuing dysregulated pro-and anti-oxidant enzyme genes in the nTS, RVLM and adrenal medulla requires sensory input from the carotid body demonstrating a hitherto uncharacterized role for sensory signals from the carotid body in regulating the redox state through HIF-dependent transcriptional changes in pro-and anti-oxidant enzymes (Fig. 2).

How ROS augments chemo-reflex?

Carotid body is composed of two major cell types: the type I (also called glomus) cells and type II cells. A substantial body of evidence suggests that type I cells are the initial sites of hypoxic sensing in the carotid body and these cells work in concert with the nearby afferent nerve ending as a ‘sensory unit’ (Kumar & Prabhakar, 2012). Carotid body activation by IH was not associated with changes in morphology of the chemoreceptor tissue (Peng et al., 2003; Del Rio et al., 2011), and was seen in ex vivo carotid bodies (Peng et al., 2003; Peng et al., 2009), suggesting that the altered carotid body function is due to direct effects of IH on hypoxia sensing by the glomus cells.

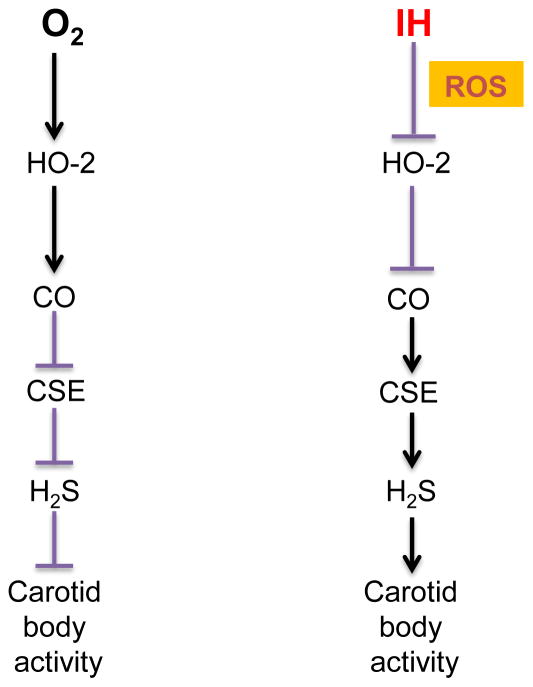

Emerging evidence suggests that hypoxia sensing by the carotid body requires carbon monoxide (CO) generation by heme oxygenase (HO)-2 and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) synthesis by cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) in glomus cells (Prabhakar & Semenza, 2015). O2 is a potent regulator of CO production from HO-2. Under normoxia, CO production is high whereas CO production is markedly decreased during hypoxia in the carotid body (Peng et al., 2010; Peng et al., 2014a; Yuan et al., 2015). The reduced CO generation, in turn activates CSE-dependent H2S synthesis through inhibition of protein kinase G-dependent phosphorylation of CSE (Yuan et al., 2015). Increased H2S levels, in turn stimulate the carotid body neural activity during hypoxia (Li et al., 2010; Peng et al., 2010; Telezhkin et al., 2010; Peng et al., 2014a; Yuan et al., 2015). However, a recent study reported that inhibitors of H2S synthesis do not prevent anoxia (zero percent oxygen)-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i and inhibition of TASK-like K+ channel of rat glomus cells (Kim et al., 2015). These findings suggest that H2S mediates carotid body response to “physiological” hypoxia.

The role of CO-H2S signaling in IH-evoked carotid body activation was examined (Yuan et al., 2016). This study showed that ROS generated during IH inhibits HO-2-dependent CO generation and this effect requires Cys265 in the heme regulatory motif of HO-2. The decreased CO in turn increases H2S production by activating CSE. Inhibiting CSE-derived H2S synthesis either by genetic knock down of CSE or by pharmacological blockade prevents the chemo- reflex activation and hypertension in IH treated rats (Yuan et al., 2016). These findings demonstrate that ROS is epistatic to H2S in driving chemo-reflex-dependent hypertension by IH (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of cellular mechanisms underlying carotid body (CB) activation by intermittent hypoxia (IH). ROS= reactive oxygen species, HO-2= heme oxygenase-2, CO= carbon monoxide, CSE= cystathionine-γ-lyase, H2S = hydrogen sulfide.

Previous studies have implicated endothelin-1 (ET-1), in mediating augmented hypoxic sensitivity of the carotid body by IH (Rey et al., 2006; Iturriaga, 2013; Peng et al., 2013). 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) and angiotensin II (Ang II) were proposed to mediate sensory LTF of IH carotid bodies (Peng et al., 2009; Peng et al., 2011b). ET-1, 5-HT and Ang II also increase ROS generation (Peng et al., 2006a; Gorąca et al., 2016). It is likely that the effects of ET-1, 5-HT and Ang II are mediated through ROS-dependent activation of H2S production, which might explain why blocking H2S production alone was sufficient to prevent the augmented hypoxic sensitivity, sensory LTF and the ensuing chemosensory reflex-mediated hypertension.

Although IH has been shown to increase ROS levels in the nTS and RVLM, how ROS affects the neuronal activity at these sites has not yet been delineated. IH-induced augmented catecholamine secretion from the adrenal medulla (Kumar et al., 2006; Souvannakitti et al., 2009; Souvannakitti et al., 2010) was shown to be mediated in part by ROS-dependent activation of protein kinase C and the resulting recruitment of readily releasable pool of secretory vesicles (Kuri et al., 2007). ROS has also been shown to facilitate Ca2+ influx via low threshold T-type Ca2+ channels as well as mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ stores by ryanodine receptor (RyR) activation in adrenal medullary chromaffin cells of IH treated rats (Souvannakitti et al., 2010).

Are the effects of IH on chemo-reflex reversible?

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the treatment of choice for OSA. However, CPAP is ineffective in normalizing blood pressures in a subset of OSA patients (Mulgrew et al., 2010; Dudenbostel & Calhoun, 2012). The efficacy of CPAP treatment might depend on the duration of OSA. A recent study examined the recovery of blood pressure and chemo-reflex in adult rats exposed to either short-term (10 days) or long-term (30 days) IH (Nanduri et al., 2016). Short-term IH-induced hypertension and the exaggerated chemo-reflex completely recovered after terminating IH (Pawar et al., 2008; Nanduri et al., 2016). In contrast, the effects elicited by long-term IH persisted 30 days after terminating IH (Nanduri et al., 2016). These findings suggest that the ineffectiveness of CPAP treatment may be a consequence of long-term IH associated with chronically undiagnosed and untreated OSA, leading to persistent activation of the chemo-reflex.

In addition to adults, recurrent apnea is also a major clinical problem in infants born pre-term. Pre-term infants with recurrent apneas often exhibit an enhanced hypoxic ventilatory response (Nock et al., 2004), a hallmark of heightened carotid body chemo-reflex. Exposing neonatal rat pups to IH simulating the apnea of prematurity also activates the chemo-reflex (Peng et al., 2004; Pawar et al., 2008). Remarkably, adult rats exposed to IH in the neonatal period exhibit augmented carotid body sensitivity to hypoxia, hypertension and irregular breathing with apnea (Pawar et al., 2008; Nanduri et al., 2012). Recent poulation based studies showed that young adults who were born preterm exhibit sleep-disordered breathing with apneas and increased incidence of hypertension (Paavonen et al., 2007; Hibbs et al., 2008). Long-lasting activation of the chemo-reflex by neonatal IH might explain the early onset of cardio-respiratory dysfunction in young adults born preterm.

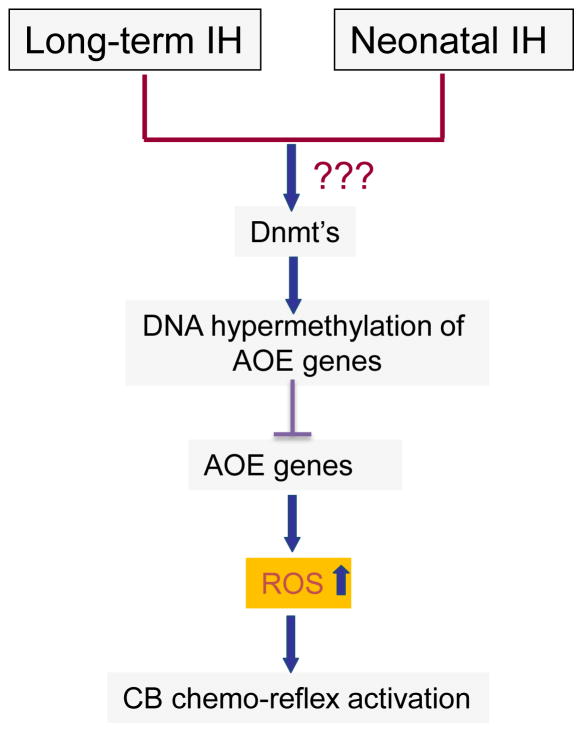

The persistent hypertension elicited by long-term and neonatal IH was associated with elevated ROS levels in the carotid bodies and adrenal medulla (Nanduri et al., 2012; Nanduri et al., 2016). The increased ROS levels were in part due to markedly reduced anti-oxidant enzyme (AOE) genes expression in the chemo-reflex pathway (Nanduri et al., 2012; Nanduri et al., 2016).

Epigenetic regulation of redox state by long-term IH

How might long-term and neonatal IH result in persistent down regulation of anti-oxidant enzyme genes? Emerging evidence suggests that epigenetic regulation by DNA methylation results in long-lasting suppression of gene expression (Feinberg, 2007). AOE genes that are downregulated by long-term and neonatal IH displayed DNA hypermethylation, and increased DNA methyl transferase (Dnmt) enzyme activity (Nanduri et al., 2012; Nanduri et al., 2016). DNA methylation occurs at cytosine residues located immediately 5′ to a guanine residue, which are known as CpG dinucleotides referred to as “CpG islands” (Illingworth & Bird, 2009). Further studies identified hypermethylation of a single CpG dinucleotide in the region close to the transcription start site of Sod2 gene in response to long-term and neonatal IH (Nanduri et al., 2012; Nanduri et al., 2016). Treating rats with decitabine, a DNA hypomethylating agent during long-term and neonatal IH exposures restored AOE gene expression, normalized ROS levels in the chemo-reflex pathway, along with normalization of blood pressures and breathing (Nanduri et al., 2012; Nanduri et al., 2016). These studies suggest that DNA methylation of AOE genes and the ensuing long-lasting oxidative stress in the chemo-reflex pathway contribute to persistent hypertension caused by long-term and neonatal IH (Fig. 4). However, the mechanism(s) by which long-term and neonatal IH activates DNA methylation remain to be investigated.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of epigenetic mechanisms (e.g., DNA hypermethylation) contributing to persistent elevation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and activation of carotid body (CB) chemo reflex by long-term intermittent hypoxia (IH) in adults and neonatal IH. Dnmts= DNA methyl transferases; AOE= anti-oxidant enzymes. CB= Carotid body.

Concluding remarks

The studies summarized in this review primarily focused on the effects of IH on chemo- reflex activation and its relevance to autonomic morbidities associated with sleep apnea. Less information is currently available on the contribution of other changes associated with sleep apnea such as mild hypercapnia, changes in intra thoracic pressure and sleep fragmentation to cardio-respiratory pathologies. Much need to be studied as to the role of other epigenetic mechanisms including histone modifications and small ineterfering RNAs in chemo-reflex driven hypertension by sleep apnea.

Central sleep apnea (CSA) patients, like OSA subjects also exhibit exaggerated chemo-reflex and are greatly at increased risk of hypertension (Solin et al., 2000). In both OSA and CSA, the acute elevations in blood pressures occurring during apneic episodes may predispose patients to hemorrhagic stroke, while chronic hypertension increases the risk of heart failure. Thus, controlling hypertension in sleep apnea patients is a major clinical problem. CPAP, which is the present treatment of choice for OSA, is not always effective in a subset of patients (Thomas et al., 2004), and treatment options for CSA are even more limited. Thus, there is an absolute need for alternative therapeutic strategies for controlling blood pressure in patients with sleep apnea. IH, which occurs in both OSA and CSA produces hypertension and marked elevations in blood pressures during simulated apneic episodes in rodents, and these effects are prevented by carotid body ablation (Fletcher et al., 1992; Peng et al., 2014b). However, removal of the carotid bodies as a therapeutic strategy in sleep apnea patients has serious limitations. Carotid body removal adversely affects many of the physiological functions including high altitude adaptation, maintenance of arterial blood gases during exercise, and cardio-respiratory responses to acute hypoxia. On the other hand, reducing the IH-induced heightened carotid body activity by pharmacological approaches might be a viable therapeutic option for normalizing blood pressures in sleep apnea patients. Although ROS signaling is central to IH-evoked carotid body hyperexcitability and the ensuing chemo-reflex, anti-oxidants have limited therapeutic value. Anti-oxidants must be administered during the entire duration of IH exposure in order to normalize carotid body function and hypertension, and when given after the onset of heightened chemo-reflex they are totally ineffective in normalizing carotid body function (Peng et al., 2003). A recent study by Yuan et al. (2016) showed that systemic administration of L-propargyl glycine (L-PAG, 30 mg/kg; IP), an inhibitor of CSE-dependent H2S synthesis given after the onset of IH-induced hypertension normalizes the carotid body activity, sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure. Thus, inhibitors of CSE-derived H2S synthesis may be a novel approach to treat chemo-reflex driven hypertension in patients with sleep apnea.

Acknowledgments

I am greatly indebted to my colleagues Drs. G. K. Kumar, J. Nanduri, Y-J. Peng and G. Yuan for their invaluable contributions to many of the studies reported in this article. Research in my laboratory is supported by National Institutes of Health grants P01-HL-90554 and UH2-HL-123610.

References

- Ambrosio G, Zweier JL, Duilio C, Kuppusamy P, Santoro G, Elia PP, Tritto I, Cirillo P, Condorelli M, Chiariello M. Evidence that mitochondrial respiration is a source of potentially toxic oxygen free radicals in intact rabbit hearts subjected to ischemia and reflow. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18532–18541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachoo M, Polosa C. Properties of a sympatho-inhibitory and vasodilator reflex evoked by superior laryngeal nerve afferents in the cat. J Physiol. 1985;364:183–198. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson JT, Hedner J, Elam M, Ejnell H, Sellgren J, Wallin BG. Augmented resting sympathetic activity in awake patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1993;103:1763–1768. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.6.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreau A, El Hafny-Rahbi B, Matejuk A, Grillon C, Kieda C. Why is the partial oxygen pressure of human tissues a crucial parameter? Small molecules and hypoxia. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1239–1253. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carulli D, Foscarin S, Rossi F. Activity-dependent plasticity and gene expression modifications in the adult CNS. Front Mol Neurosci. 2011;4:50. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cistulli PA, Sullivan CE. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. In: Saunders Na, Sullivan Ce., editors. Sleep and Breathing. Dekker; New York: 1994. pp. 405–448. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Silva JH, Zoccal DB, Machado BH. Chronic intermittent hypoxia alters glutamatergic control of sympathetic and respiratory activities in the commissural NTS of rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R785–793. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00363.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampney RA. Functional organization of central pathways regulating the cardiovascular system. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:323–364. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Burgh Daly M. Chemoreceptor reflexes and cardiovascular control. Acta Physiol Pol. 1985;36:4–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Burgh Daly M, Lambertsen CJ, Schweitzer A. Observations on the volume of blood flow and oxygen utilization of the carotid body in the cat. J Physiol. 1954;125:67–89. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paula PM, Tolstykh G, Mifflin S. Chronic intermittent hypoxia alters NMDA and AMPA-evoked currents in NTS neurons receiving carotid body chemoreceptor inputs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R2259–2265. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00760.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rio R, Munoz C, Arias P, Court FA, Moya EA, Iturriaga R. Chronic intermittent hypoxia-induced vascular enlargement and VEGF upregulation in the rat carotid body is not prevented by antioxidant treatment. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L702–711. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00128.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey JA, Sheel AW, St Croix CM, Morgan BJ. Respiratory influences on sympathetic vasomotor outflow in humans. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2002;130:3–20. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(01)00327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O’Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:47–112. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudenbostel T, Calhoun DA. Resistant hypertension, obstructive sleep apnoea and aldosterone. J Hum Hypertens. 2012;26:281–287. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2011.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ema M, Taya S, Yokotani N, Sogawa K, Matsuda Y, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. A novel bHLH-PAS factor with close sequence similarity to hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha regulates the VEGF expression and is potentially involved in lung and vascular development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4273–4278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg AP. Phenotypic plasticity and the epigenetics of human disease. Nature. 2007;447:433–440. doi: 10.1038/nature05919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields RD, Lee PR, Cohen JE. Temporal integration of intracellular Ca2+ signaling networks in regulating gene expression by action potentials. Cell Calcium. 2005;37:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher EC. An animal model of the relationship between systemic hypertension and repetitive episodic hypoxia as seen in sleep apnoea. J Sleep Res. 1995;4:71–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1995.tb00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher EC, Lesske J, Behm R, Miller CC, 3rd, Stauss H, Unger T. Carotid chemoreceptors, systemic blood pressure, and chronic episodic hypoxia mimicking sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:1978–1984. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.5.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher EC, Miller J, Schaaf JW, Fletcher JG. Urinary catecholamines before and after tracheostomy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension. Sleep. 1987;10:35–44. doi: 10.1093/sleep/10.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly K, Poo MM. Activity-dependent neural plasticity from bench to bedside. Neuron. 2013;80:729–741. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rio F, Racionero MA, Pino JM, Martinez I, Ortuno F, Villasante C, Villamor J. Sleep apnea and hypertension. Chest. 2000;117:1417–1425. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorąca A, Kleniewska P, Skibska B. ET-1 mediates the release of reactive oxygen species and TNF-α in lung tissue by protein kinase C α and β1. Pharmacol Rep. 2016;68:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG. Neural structures that mediate sympathoexcitation during hypoxia. Respir Physiol. 2000;121:147–162. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haselton JR, Guyenet PG. Central respiratory modulation of medullary sympathoexcitatory neurons in rat. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:R739–750. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.256.3.R739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedner JA, Wilcox I, Laks L, Grunstein RR, Sullivan CE. A specific and potent pressor effect of hypoxia in patients with sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:1240–1245. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.5_Pt_1.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs AM, Johnson NL, Rosen CL, Kirchner HL, Martin R, Storfer-Isser A, Redline S. Prenatal and neonatal risk factors for sleep disordered breathing in school-aged children born preterm. J Pediatr. 2008;153:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Lusina S, Xie T, Ji E, Xiang S, Liu Y, Weiss JW. Sympathetic response to chemostimulation in conscious rats exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;166:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illingworth RS, Bird AP. CpG islands--’a rough guide’. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1713–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturriaga R. Intermittent hypoxia: endothelin-1 and hypoxic carotid body chemosensory potentiation. Exp Physiol. 2013;98:1550–1551. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.075820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara T, Narkiewicz K, Somers VK. Chemoreflexes--physiology and clinical implications. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;177:377–384. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SA, Nanduri J, Yuan G, Kinsman B, Kumar GK, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B, Prabhakar NR. NADPH oxidase 2 mediates intermittent hypoxia-induced mitochondrial complex I inhibition: relevance to blood pressure changes in rats. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:533–542. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Kim I, Wang J, White C, Carroll JL. Hydrogen sulfide and hypoxia-induced changes in TASK (K2P3/9) activity and intracellular Ca(2+) concentration in rat carotid body glomus cells. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2015;215:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD, Ramirez-Navarro A, Kunze DL. Adaptive depression in synaptic transmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract after in vivo chronic intermittent hypoxia: evidence for homeostatic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4663–4673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4946-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar GK, Rai V, Sharma SD, Ramakrishnan DP, Peng YJ, Souvannakitti D, Prabhakar NR. Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces hypoxia-evoked catecholamine efflux in adult rat adrenal medulla via oxidative stress. J Physiol. 2006;575:229–239. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.112524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Prabhakar NR. Peripheral chemoreceptors: function and plasticity of the carotid body. Comprehensive Physiology. 2012;2:141–219. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuri BA, Khan SA, Chan SA, Prabhakar NR, Smith CB. Increased secretory capacity of mouse adrenal chromaffin cells by chronic intermittent hypoxia: involvement of protein kinase C. J Physiol. 2007;584:313–319. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.140624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam SY, Liu Y, Ng KM, Lau CF, Liong EC, Tipoe GL, Fung ML. Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces local inflammation of the rat carotid body via functional upregulation of proinflammatory cytokine pathways. Histochem Cell Biol. 2012;137:303–317. doi: 10.1007/s00418-011-0900-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie P, Herer P, Hoffstein V. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome as a risk factor for hypertension: population study. BMJ. 2000;320:479–482. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesske J, Fletcher EC, Bao G, Unger T. Hypertension caused by chronic intermittent hypoxia--influence of chemoreceptors and sympathetic nervous system. J Hypertens. 1997;15:1593–1603. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715120-00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Sun B, Wang X, Jin Z, Zhou Y, Dong L, Jiang LH, Rong W. A crucial role for hydrogen sulfide in oxygen sensing via modulating large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:1179–1189. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longobardo GS, Gothe B, Goldman MD, Cherniack NS. Sleep apnea considered as a control system instability. Respir Physiol. 1982;50:311–333. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrone O, Riccobono L, Salvaggio A, Mirabella A, Bonanno A, Bonsignore MR. Catecholamines and blood pressure in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1993;103:722–727. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.3.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllen RM. Central respiratory modulation of subretrofacial bulbospinal neurones in the cat. J Physiol. 1987;388:533–545. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki T, Pilowsky P, Sun QJ, Minson J, Suzuki S, Arnolda L, Llewellyn-Smith I, Chalmers J. Central inspiration increases barosensitivity of neurons in rat rostral ventrolateral medulla. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:R909–918. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.4.R909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes DJ, da Silva MP, Bonagamba LG, Mecawi AS, Zoccal DB, Antunes-Rodrigues J, Varanda WA, Machado BH. Electrophysiological properties of rostral ventrolateral medulla presympathetic neurons modulated by the respiratory network in rats. J Neurosci. 2013;33:19223–19237. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3041-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes DJ, Machado BH, Paton JF. Carotid body overactivity induces respiratory neurone channelopathy contributing to neurogenic hypertension. J Physiol. 2015;593:3055–3063. doi: 10.1113/JP270423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulgrew AT, Lawati NA, Ayas NT, Fox N, Hamilton P, Cortes L, Ryan CF. Residual sleep apnea on polysomnography after 3 months of CPAP therapy: clinical implications, predictors and patterns. Sleep Med. 2010;11:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanduri J, Makarenko V, Reddy VD, Yuan G, Pawar A, Wang N, Khan SA, Zhang X, Kinsman B, Peng Y-J, Kumar GK, Fox AP, Godley LA, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Epigenetic regulation of hypoxic sensing disrupts cardiorespiratory homeostasis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:2515–2520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120600109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanduri J, Peng Y-J, Wang N, Khan S, Semenza G, Kumar GK, Prabhakar NR. Epigenetic regulation of redox state mediates persistent cardiorespiratory abnormalities after long-term intermittent hypoxia. J Physiol. 2016 doi: 10.1113/JP272346. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanduri J, Vaddi DR, Khan SA, Wang N, Makerenko V, Prabhakar NR. Xanthine oxidase mediates hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha degradation by intermittent hypoxia. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanduri J, Wang N, Yuan G, Khan S, Souvannakitti D, Peng Y-J, Kumar GK, Garcia JA. HIF-2 alpha down-regulation by intermittent hypoxia in rats induces oxidative stress resulting in autonomic dysfunction. Faseb Journal. 2009a:23. [Google Scholar]

- Nanduri J, Wang N, Yuan G, Khan SA, Souvannakitti D, Peng YJ, Kumar GK, Garcia JA, Prabhakar NR. Intermittent hypoxia degrades HIF-2alpha via calpains resulting in oxidative stress: implications for recurrent apnea-induced morbidities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009b;106:1199–1204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811018106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkiewicz K, Somers VK. The sympathetic nervous system and obstructive sleep apnea: implications for hypertension. J Hypertens. 1997;15:1613–1619. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715120-00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkiewicz K, van de Borne PJ, Pesek CA, Dyken ME, Montano N, Somers VK. Selective potentiation of peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity in obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation. 1999;99:1183–1189. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.9.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, Shahar E, Samet JM, Redline S, D’Agostino RB, Newman AB, Lebowitz MD, Pickering TG. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA. 2000;283:1829–1836. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock ML, Difiore JM, Arko MK, Martin RJ. Relationship of the ventilatory response to hypoxia with neonatal apnea in preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2004;144:291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paavonen EJ, Strang-Karlsson S, Räikkönen K, Heinonen K, Pesonen AK, Hovi P, Andersson S, Järvenpää AL, Eriksson JG, Kajantie E. Very low birth weight increases risk for sleep-disordered breathing in young adulthood: the Helsinki Study of Very Low Birth Weight Adults. Pediatrics. 2007;120:778–784. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawar A, Peng Y-J, Jacono FJ, Prabhakar NR. Comparative analysis of neonatal and adult rat carotid body responses to chronic intermittent hypoxia. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2008;104:1287–1294. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00644.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y-J, Nanduri J, Raghuraman G, Souvannakitti D, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH, Prabhakar NR. H2S mediates O-2 sensing in the carotid body. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10719–10724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005866107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Makarenko VV, Nanduri J, Vasavda C, Raghuraman G, Yuan G, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH, Prabhakar NR. Inherent variations in CO-H2S-mediated carotid body O2 sensing mediate hypertension and pulmonary edema. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014a;111:1174–1179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322172111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Nanduri J, Khan SA, Yuan G, Wang N, Kinsman B, Vaddi DR, Kumar GK, Garcia JA, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha (HIF-2alpha) heterozygous-null mice exhibit exaggerated carotid body sensitivity to hypoxia, breathing instability, and hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011a;108:3065–3070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100064108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Nanduri J, Raghuraman G, Wang N, Kumar GK, Prabhakar NR. Role of oxidative stress-induced endothelin-converting enzyme activity in the alteration of carotid body function by chronic intermittent hypoxia. Exp Physiol. 2013;98:1620–1630. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.073700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Nanduri J, Yuan G, Wang N, Deneris E, Pendyala S, Natarajan V, Kumar GK, Prabhakar NR. NADPH oxidase is required for the sensory plasticity of the carotid body by chronic intermittent hypoxia. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4903–4910. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4768-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Overholt JL, Kline D, Kumar GK, Prabhakar NR. Induction of sensory long-term facilitation in the carotid body by intermittent hypoxia: implications for recurrent apneas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10073–10078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1734109100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Prabhakar NR. Effect of two paradigms of chronic intermittent hypoxia on carotid body sensory activity. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1236–1242. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00820.2003. discussion 1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Raghuraman G, Khan SA, Kumar GK, Prabhakar NR. Angiotensin II evokes sensory long-term facilitation of the carotid body via NADPH oxidase. J Appl Physiol. 2011b;111:964–970. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00022.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Rennison J, Prabhakar NR. Intermittent hypoxia augments carotid body and ventilatory response to hypoxia in neonatal rat pups. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:2020–2025. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00876.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Yuan G, Jacono FJ, Kumar GK, Prabhakar NR. 5-HT evokes sensory long-term facilitation of rodent carotid body via activation of NADPH oxidase. J Physiol. 2006a;576:289–295. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.116020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Yuan G, Khan S, Nanduri J, Makarenko VV, Reddy VD, Vasavda C, Kumar GK, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-α isoforms and redox state by carotid body neural activity in rats. J Physiol. 2014b;592:3841–3858. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.273789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Yuan G, Ramakrishnan D, Sharma SD, Bosch-Marce M, Kumar GK, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Heterozygous HIF-1alpha deficiency impairs carotid body-mediated systemic responses and reactive oxygen species generation in mice exposed to intermittent hypoxia. J Physiol. 2006b;577:705–716. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:1006–1014. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1378–1384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar NR. Oxygen sensing during intermittent hypoxia: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:1986–1994. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.5.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar NR. Sensing hypoxia: physiology, genetics and epigenetics. J Physiol. 2013;591:2245–2257. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.247759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar NR, Semenza GL. Adaptive and maladaptive cardiorespiratory responses to continuous and intermittent hypoxia mediated by hypoxia-inducible factors 1 and 2. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:967–1003. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar NR, Semenza GL. Oxygen Sensing and Homeostasis. Physiology (Bethesda) 2015;30:340–348. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00022.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves SR, Gozal E, Guo SZ, Sachleben LR, Jr, Brittian KR, Lipton AJ, Gozal D. Effect of long-term intermittent and sustained hypoxia on hypoxic ventilatory and metabolic responses in the adult rat. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:1767–1774. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00759.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey S, Del Rio R, Alcayaga J, Iturriaga R. Chronic intermittent hypoxia enhances cat chemosensory and ventilatory responses to hypoxia. J Physiol. 2004;560:577–586. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.072033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey S, Del Rio R, Iturriaga R. Contribution of endothelin-1 to the enhanced carotid body chemosensory responses induced by chronic intermittent hypoxia. Brain Res. 2006;1086:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solin P, Roebuck T, Johns DP, Walters EH, Naughton MT. Peripheral and central ventilatory responses in central sleep apnea with and without congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:2194–2200. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.2002024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers VK, Dyken ME, Clary MP, Abboud FM. Sympathetic neural mechanisms in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1897–1904. doi: 10.1172/JCI118235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souvannakitti D, Kumar GK, Fox A, Prabhakar NR. Neonatal intermittent hypoxia leads to long-lasting facilitation of acute hypoxia-evoked catecholamine secretion from rat chromaffin cells. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:2837–2846. doi: 10.1152/jn.00036.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souvannakitti D, Nanduri J, Yuan G, Kumar GK, Fox AP, Prabhakar NR. NADPH oxidase-dependent regulation of T-type Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors mediate the augmented exocytosis of catecholamines from intermittent hypoxia-treated neonatal rat chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10763–10772. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2307-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stornetta RL, Sevigny CP, Schreihofer AM, Rosin DL, Guyenet PG. Vesicular glutamate transporter DNPI/VGLUT2 is expressed by both C1 adrenergic and nonaminergic presympathetic vasomotor neurons of the rat medulla. J Comp Neurol. 2002;444:207–220. doi: 10.1002/cne.10142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafil-Klawe M, Thiele AE, Raschke F, Mayer J, Peter JH, von Wichert W. Peripheral chemoreceptor reflex in obstructive sleep apnea patients; a relationship between ventilatory response to hypoxia and nocturnal bradycardia during apnea events. Pneumologie. 1991;45(Suppl 1):309–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamisier R, Pepin JL, Remy J, Baguet JP, Taylor JA, Weiss JW, Levy P. 14 nights of intermittent hypoxia elevate daytime blood pressure and sympathetic activity in healthy humans. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:119–128. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00204209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telezhkin V, Brazier SP, Cayzac SH, Wilkinson WJ, Riccardi D, Kemp PJ. Mechanism of inhibition by hydrogen sulfide of native and recombinant BKCa channels. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;172:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas RJ, Terzano MG, Parrino L, Weiss JW. Obstructive sleep-disordered breathing with a dominant cyclic alternating pattern--a recognizable polysomnographic variant with practical clinical implications. Sleep. 2004;27:229–234. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H, McKnight SL, Russell DW. Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1), a transcription factor selectively expressed in endothelial cells. Genes Dev. 1997;11:72–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Adhikary G, McCormick AA, Holcroft JJ, Kumar GK, Prabhakar NR. Role of oxidative stress in intermittent hypoxia-induced immediate early gene activation in rat PC12 cells. J Physiol. 2004;557:773–783. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Khan SA, Luo W, Nanduri J, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 mediates increased expression of NADPH oxidase-2 in response to intermittent hypoxia. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:2925–2933. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Nanduri J, Khan S, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Induction of HIF-1alpha expression by intermittent hypoxia: involvement of NADPH oxidase, Ca2+ signaling, prolyl hydroxylases, and mTOR. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217:674–685. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Peng Y-J, Khan S, Nanduri J, Singh A, Vasavda C, Semenza G, Kumar G, Snyder S, Prabhakar N. H2S production by reactive oxygen species in the carotid body triggers hypertension in a rodent model of sleep apnea. Sci Signal. 2016 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaf3204. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Vasavda C, Peng YJ, Makarenko VV, Raghuraman G, Nanduri J, Gadalla MM, Semenza GL, Kumar GK, Snyder SH, Prabhakar NR. Protein kinase G-regulated production of H2S governs oxygen sensing. Sci Signal. 2015;8:ra37. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan G, Serrano F, Fenik P, Hsu R, Kong L, Pratico D, Klann E, Veasey SC. NADPH oxidase mediates hypersomnolence and brain oxidative injury in a murine model of sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:921–929. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200504-581OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]