Most strains of Neisseria gonorrheae (Ng), the causative agent of the sexually transmitted disease gonorrheae, and a few strains of Neisseria meningitidis (Nm), which is responsible for a large number of meningitides, harbor a 57-kb horizontally acquired genetic element, the gonococcal genomic island (GGI) (1–3). Certain versions of the GGI are associated with disseminated gonococcal infection (1, 4). In addition, the GGI encodes numerous homologs of type IV secretion system genes, which are necessary for DNA secretion and facilitate natural transformation of the Neisseria (1, 2, 4). GGI are found integrated at the chromosomal dimer resolution site of their host chromosome, dif, and are flanked by a partial repeat of it, difGGI (Fig. 1A) (1, 5). The dif site is the target of two highly conserved chromosomally encoded tyrosine recombinases, XerC and XerD, which normally serve to resolve dimers of circular chromosomes through the addition of a crossover between directly repeated dif sites (6). This reaction raises questions on how GGI could be stably maintained (5). The results presented by Fournes et al. (7) in PNAS shed a new light on this apparent paradox.

Fig. 1.

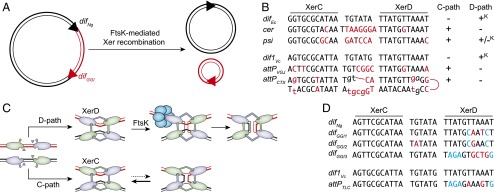

(A) Schematic of XerCD-mediated excision of the GGI. Black double lines, N. gonorrheae chromosomal DNA; red double lines, GGI DNA; black triangles, difNg and red triangle, difGGI. (B) Sequence alignment of the Xer recombination site of mobile elements and their cognate partner chromosomal dif site; attPCTX, CTXϕ attachment site; attPVGJ, VGJϕ attachment site; cer, core dimer resolution site of plasmid ColE1; difEc, E. coli dif; dif1Vc, V. cholerae chr1 dif; and psi, core dimer resolution site of plasmid pSC101. Apart from attPCTX, which is the stem of a forked hairpin from the single-stranded form of the genome of CTXϕ, a single of the two DNA strands is represented in the 5′ to 3′ orientation from left to right. Bases of cer and psi that differ from difEc and bases from attPCTX and attPVGJ that differ from dif1Vc are indicated in red. Plus (+) and minus (–) signs indicate whether the sites can engage in recombination pathways initiated by XerC or XerD strand exchanges; +K denotes FtsK-dependent recombination pathways. (C) Schematic of Xer recombination. XerD and XerC are represented in magenta and green, respectively. Following the Cre paradigm, the active pair of recombinases are drawn with their extreme C-terminal domains contacting the partner recombinases in cis. Blue circles represent the hexamer of FtsK. (D) Sequence alignment of difNg, the three different types of difGGI, dif1Vc, and attPTLC. Bases of the dif-like site of mobile elements that differ from their cognate dif partner are highlighted in color, with blue highlighting those that are identical in difGGI1 and difGGI2 and in attPGGI3 and attPTLC.

The Xer machinery is highly conserved in bacteria. The dif sites consist of 11-bp XerC- and XerD-binding motifs, separated by an overlap region at the border of which recombination occurs (Fig. 1B). Recombination is under the control of a hexameric DNA pump, FtsK (Fig. 1C) (8). FtsK is a powerful translocase (9) and strips DNA from most proteins (10). However, a direct interaction between its extreme C-terminal domain, FtsKγ, and the Xer recombinases stops it (Fig. 1C) (11, 12) and activates the exchange of a pair of strands by XerD catalysis when in the presence of a synaptic complex (Fig. 1C) (8, 11, 13). The exchange of a second pair of strands by XerC catalysis converts the resulting Holliday junction into product (Fig. 1C) (8, 13). FtsK belongs to the cell division machinery. It assembles at midcell when most of the chromosomal DNA has been replicated and segregated, which restricts recombination at dif to the time of cell division (14, 15) and to the chromosome replication terminus region (16, 17).

Numerous mobile elements have been shown to exploit Xer recombination. Plasmids use it for the resolution of multimers, the formation of which compromises vertical transmission from mother to daughters by reducing the number of independently segregating plasmid units (18). Integrating mobile element exploiting Xer (IMEX) use it to insert into the dif site of one of the chromosomes of their host (19). In both cases, the FtsK control imposed on Xer recombination must be overcome, because the replication/segregation cycle of plasmids and the integration/excision cycle of IMEX should be independent from the cell cycle. Moreover, Xer recombination leads to the formation of plasmid multimers when they harbor a dif site (17, 20) and to the excision of the intervening DNA between directly repeated dif sites (17, 21). Correspondingly, the central region of plasmid sites seems to prevent FtsK-dependent XerD catalysis (Fig. 1B) (22), and the central region of the attachment sites of most IMEX lacks the necessary homology to stabilize XerD-mediated strand exchanges with dif (Fig. 1B) (23, 24). This is not the case for the central region of the different alleles of difGGI (Fig. 1D). The problem was most striking for the most common of these alleles, difGGI1, which differs from the neisserial dif by only 4 bp (Fig. 1D).

In PNAS, Fournes et al. (7) observe that the Ng Xer recombinases efficiently bound to difGGI1, synapsed it with difNg, and catalyzed complete recombination reactions between the two sites when activated by Ng FtsKγ. However, they noticed that recombination was reduced in the presence of the FtsK translocation module. The authors smartly hypothesize that FtsK translocation inhibited recombination by stripping Ng XerD from difGGI1, which they successfully verified in vitro.

It was previously suggested that GGI initially harbored true neisserial dif sites and that their stabilization resulted from mutations that occurred after their integration (5). Many different types of mutations, including mutations in the central region of the dif sites and mutations abolishing the binding of the recombinases to them, could impede Xer recombination. Why, then, should difGGI1 harbor mutations that blocked FtsK-dependent recombination without affecting XerC and XerD binding and synapse formation? One of the difGGI alleles found in Nm strains, attPGGI2, harbors two out of four of the bases that differentiate difGG1 from difNg, which suggests that these changes were not randomly picked up (Fig. 1D, blue bases of difGGI1 and difGGI2). Indeed, it is striking to note that difGGI2 is fully palindromic and carries two XerC-binding arms (Fig. 1D). In contrast, 8 out 11 of the bases of the XerD-binding arm of difGGI3 differentiate it from the XerD arm of dif sites (Fig. 1D). The attachment site of a V. cholerae IMEX, the toxin-linked cryptic phage (TLCϕ) harbors four of these bases (Fig. 1D, blue bases of difGGI3 and attPTLC) (25). We previously demonstrated that XerD poorly bound to attPTLC, which is sufficient to prevent XerD-mediated FtsK-dependent recombination (25). Thus, it is tempting to propose that GGI are IMEX and difGGI sites were selected not only to escape but also to overcome the normal cellular control imposed on Xer recombination by FtsK. GGI harboring difGGI3 probably belong to the TLCϕ class of IMEX, which integrate into and excise from the genome of their host via a XerD-first FtsK-independent recombination pathway (25). GGI harboring difGGI1 and difGGI2 probably define a new class of IMEX. Future work will need to address the Xer recombination pathway they exploit and if they can truly integrate independently of FtsK. In addition, it will be interesting to determine which factors encoded in the genome of GGI IMEX and/or in the genome of their host help them overcome the cellular control that is normally imposed on Xer recombination, as observed for plasmids (18) and the CTXϕ class of IMEX (26).

Acknowledgments

Research in the F.-X.B. laboratory is funded by the European Research Council under the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013 Grant Agreement 281590).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 7882 in issue 28 of volume 113.

References

- 1.Dillard JP, Seifert HS. A variable genetic island specific for Neisseria gonorrhoeae is involved in providing DNA for natural transformation and is found more often in disseminated infection isolates. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41(1):263–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton HL, Domínguez NM, Schwartz KJ, Hackett KT, Dillard JP. Neisseria gonorrhoeae secretes chromosomal DNA via a novel type IV secretion system. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55(6):1704–1721. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snyder LAS, Jarvis SA, Saunders NJ. Complete and variant forms of the ‘gonococcal genetic island’ in Neisseria meningitidis. Microbiology. 2005;151(Pt 12):4005–4013. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27925-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamilton HL, Schwartz KJ, Dillard JP. Insertion-duplication mutagenesis of Neisseria: Use in characterization of DNA transfer genes in the gonococcal genetic island. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(16):4718–4726. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.16.4718-4726.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domínguez NM, Hackett KT, Dillard JP. XerCD-mediated site-specific recombination leads to loss of the 57-kilobase gonococcal genetic island. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(2):377–388. doi: 10.1128/JB.00948-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Midonet C, Barre F-X. Xer site-specific recombination: Promoting vertical and horizontal transmission of genetic information. Microbiol Spectrum. 2014;2(6):MDNA3-0056-2014. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0056-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fournes F, et al. FtsK translocation permits discrimination between an endogenous and an imported Xer/dif recombination complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(28):7882–7887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523178113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aussel L, et al. FtsK is a DNA motor protein that activates chromosome dimer resolution by switching the catalytic state of the XerC and XerD recombinases. Cell. 2002;108(2):195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00624-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saleh OA, Pérals C, Barre FX, Allemand JF. Fast, DNA-sequence independent translocation by FtsK in a single-molecule experiment. EMBO J. 2004;23(12):2430–2439. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JY, Finkelstein IJ, Arciszewska LK, Sherratt DJ, Greene EC. Single-molecule imaging of FtsK translocation reveals mechanistic features of protein-protein collisions on DNA. Mol Cell. 2014;54(5):832–843. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.May PFJ, Zawadzki P, Sherratt DJ, Kapanidis AN, Arciszewska LK. Assembly, translocation, and activation of XerCD-dif recombination by FtsK translocase analyzed in real-time by FRET and two-color tethered fluorophore motion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(37):E5133–E5141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510814112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham JE, Sivanathan V, Sherratt DJ, Arciszewska LK. FtsK translocation on DNA stops at XerCD-dif. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(1):72–81. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zawadzki P, et al. Conformational transitions during FtsK translocase activation of individual XerCD−dif recombination complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(43):17302–17307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311065110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy SP, Chevalier F, Barre FX. Delayed activation of Xer recombination at dif by FtsK during septum assembly in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68(4):1018–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steiner WW, Kuempel PL. Cell division is required for resolution of dimer chromosomes at the dif locus of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27(2):257–268. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deghorain M, et al. A defined terminal region of the E. coli chromosome shows late segregation and high FtsK activity. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e22164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barre FX, et al. FtsK functions in the processing of a Holliday junction intermediate during bacterial chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 2000;14(23):2976–2988. doi: 10.1101/gad.188700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colloms SD. The topology of plasmid-monomerizing Xer site-specific recombination. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41(2):589–594. doi: 10.1042/BST20120340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das B, Martínez E, Midonet C, Barre F-X. Integrative mobile elements exploiting Xer recombination. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Recchia GD, Aroyo M, Wolf D, Blakely G, Sherratt DJ. FtsK-dependent and -independent pathways of Xer site-specific recombination. EMBO J. 1999;18(20):5724–5734. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.20.5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pérals K, Cornet F, Merlet Y, Delon I, Louarn JM. Functional polarization of the Escherichia coli chromosome terminus: The dif site acts in chromosome dimer resolution only when located between long stretches of opposite polarity. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36(1):33–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Capiaux H, Lesterlin C, Pérals K, Louarn JM, Cornet F. A dual role for the FtsK protein in Escherichia coli chromosome segregation. EMBO Rep. 2002;3(6):532–536. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das B, Bischerour J, Val M-E, Barre F-X. Molecular keys of the tropism of integration of the cholera toxin phage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(9):4377–4382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910212107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das B, Bischerour J, Barre F-X. VGJϕ integration and excision mechanisms contribute to the genetic diversity of Vibrio cholerae epidemic strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(6):2516–2521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017061108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Midonet C, Das B, Paly E, Barre F-X. XerD-mediated FtsK-independent integration of TLCϕ into the Vibrio cholerae genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(47):16848–16853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404047111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bischerour J, Spangenberg C, Barre F-X. Holliday junction affinity of the base excision repair factor Endo III contributes to cholera toxin phage integration. EMBO J. 2012;31(18):3757–3767. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]