Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate interreader and inter-test agreement in applying size- and necrosis-based response assessment criteria after transarterial embolization (TAE) for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), applying two different methods of European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) criteria.

Methods and Materials

Seventy-four patients (median age, 67 years) from a prospectively accrued study population were included in this retrospective study. Four radiologists independently evaluated CT data at 2–3 (1st FU) and 10–12 (2nd FU) weeks after TAE and assessed treatment response using size-based (WHO, RECIST) and necrosis-based criteria (mRECIST, EASL) criteria. Enhancing tissue was bidimensionally measured (EASLmeas) and also visually estimated (EASLest). Interreader and inter-test agreement were assessed using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and κ statistics.

Results

Interreader agreement for all response assessment methods ranged from moderate to substantial (κ=0.578–0.700) at 1st follow-up and was substantial (κ=0.716–0.780) at 2nd follow-up. Inter-test agreement was substantial between WHO and RECIST (κ=0.610–0.799, 1st FU; κ=0.655–0.782, 2nd FU) and excellent between EASLmeas and EASLest (κ=0.899–0.918, 1st FU; κ=0.843–0.877, 2nd FU).

Conclusion

Size- and necrosis-based criteria both show moderate to excellent interreader agreement in evaluating treatment response after TAE for HCC. Inter-test agreement regarding EASLmeas and EASLest was excellent, suggesting that either may be used.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, response assessment, interreader agreement, transarterial therapy, embolization

Introduction

In selected patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the use of transarterial chemoembolization rather than conservative treatment has been shown to improve survival [1, 2]. Other methods of transarterial therapy, including transarterial embolization, embolization with drug-eluting beads and radioembolization with Yttrium 90, have also been used to treat HCC [3–6]. Cross-sectional imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been recommended for assessing the response to such transarterial treatments [7].

The response assessment criteria of the World Health Organization (WHO) are based on bidimensional measurement of lesion size [8], while the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) [9] are based on unidimensional lesion measurement. However, after transarterial embolization, tumour necrosis (manifest as a lack of tumour enhancement) may be seen before any changes in tumour size become apparent, and in some cases, necrosis may not be followed by any reduction in tumour size. Therefore, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) proposed criteria for assessing treatment response in HCC based on lesion enhancement instead of lesion size [7], and subsequently, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) proposed to incorporate changes in tumour enhancement in a modified version of RECIST (mRECIST) [10]. In recent studies, response evaluation criteria incorporating enhancement characteristics (mRECIST, EASL) predicted long-term survival of HCC patients treated with transarterial methods earlier and more accurately than did size-based criteria (e.g. WHO, RECIST) [11–13]. As a result, the use of EASL criteria to establish patients’ response to transarterial embolization has increased [14].

The EASL has never specified precisely how to apply the EASL criteria to quantify the change in tumour enhancement [7]. In some studies investigators have estimated the percent change in tumour enhancement visually, as is often done in clinical practice [14, 15]; however, in other studies, the enhancing tissue has been measured uni- [16] or bidimensionally [11, 17] or by using a volumetric approach [18–21]. Furthermore, in all of these studies, the magnitude of response was decided in consensus without analyzing interreader agreement. In clinical practice, images are hardly ever evaluated in consensus, but rather are assessed by individual radiologists of different experience levels [22].

It is important to assess reader agreement with regard to quantitative assessments, particularly when such assessments influence patient management [22]. Thus, the purpose of our study was to evaluate interreader and inter-test agreement in applying size- and necrosis-based response assessment criteria after transarterial embolization for HCC, using two different methods of applying the EASL criteria.

Materials and Methods

Patients

From November 2007 through March 2012, 92 patients undergoing transarterial embolization using microspheres for surgically unresectable HCC were included in a prospective trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: blinded for review) aimed at comparing the effect between embolization using Bead Block™ microspheres versus doxorubicin-loaded LC Bead™. Diagnosis of HCC was based on the EASL criteria [7]. For our retrospective analysis, patients were excluded if their imaging follow-up was not performed by CT or if there was no target lesion, defined as a nodular, non infiltrative lesion with a diameter of ≥ 1cm permitting repetitive measurement according to the mRECIST guidelines [10, 11]. Further inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

CT Acquisition and Follow Up

Triphasic CTs were acquired on a multidetector CT (LightSpeed 16, VCT and CT750, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, Wis) using the following parameters: slice thickness, 5 mm for all phases; pitch, 0.984–1.375; gantry rotation time, 0.7–0.8 seconds; ref. tube current-time, 220–440 mA/rotation; tube voltage, 120 kV. After unenhanced images were acquired, additional images were acquired in the hepatic arterial phase (using bolus tracking) and portal venous phase (40 seconds after the hepatic arterial phase). For enhanced phases, 150 ml of iohexol 300 (Omnipaque, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) was administered intravenously with a power injector at 4 mL/s.

Baseline CT was performed 22.6±14.4 days (range, 3–63 days) before the start of transarterial embolization. A first follow-up CT (1st FU) was planned for 2–3 weeks after transarterial embolization and a second follow-up CT (2nd FU) was planned for 10–12 weeks after transarterial embolization.

Embolization Procedure

Patients were randomized to undergo embolization of the lesion with Bead Block™ microspheres or with doxorubicin-loaded LC Bead™. The embolization technique used has been described before [4, 23]. After performing visceral angiography to establish hepatic arterial anatomy, tumour burden, and vascular supply, vessels supplying the target lesion(s) were catheterized and embolization was performed with either LC Bead™ loaded with 150mg of doxorubicin, or Bead Block™, beginning in either case with 100–300 micron particles until stasis was achieved. In the LC Bead group, if stasis was not achieved after the entire dose of doxorubicin-loaded microspheres had been delivered; additional Bead Block™ was used to achieve the stasis endpoint. If multiple small lesions were present, lobar embolization was performed instead of selective embolization. After the embolization, all patients were admitted for intravenous hydration, 24 hours of antibiotic treatment, pain control, and observation.

Image Analysis and Assessment of Response

Four radiologists (XX and XX, faculty members and XX and XX, body imaging research fellows, with 8, 10, 5 and 4 years of experience in interpreting abdominal CT, respectively) independently evaluated the CT data using electronic forms for data collection. The radiologists were blinded to clinical and laboratory findings as well as histological and imaging findings. In patients with unifocal HCC, the radiologists assessed the targeted tumour, and in patients with multifocal HCC, they selected the two largest and most easily measured lesions [24]. A target lesion was defined as a nodular, non-infiltrative lesion with a diameter ≥ 1 cm permitting repetitive measurement according to mRECIST guidelines [10, 11]. Response was assessed using size- (WHO, RECIST) and necrosis- (mRECIST, EASL) based criteria [7–10].

The readers measured the largest diameter(s) of the relevant lesion(s) uni- and bidimensionally in accordance with RECIST and WHO guidelines, respectively. To implement EASL criteria, visual volumetric assessment of enhancing tissue was performed by scrolling through all CT images covering the respective lesion and estimating the total percentage of enhancing tissue within the relevant lesion(s) in 10-percentile increments (an estimate henceforth referred to as EASLest); in addition, on the transaxial slice with the largest enhancing component, they measured the enhancing tissue bidimensionally (a measurement henceforth referred to as EASLmeas). The longer of the two dimensions recorded as EASLmeas was later used to apply mRECIST. Visual assessment of enhancing tissue was performed before measurement to avoid influencing the estimation of enhancing tissue. As microspheres were used for transarterial embolization, there were no lipiodol-induced artefacts hampering visual assessment. As per the various response assessment criteria (Table 1), responses were classified into 4 categories: complete response (CR); partial response (PR); stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD).

Table 1.

Response assessment criteria [28]

| System | Response | Definition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size Criteria | World Health Organization Guidelines (WHO) [8] | CR | Disappearance of all target lesions |

| PR | ≥50% decrease in cross-product of target lesion(s) | ||

| SD | <50% decrease to ≤25% increase in cross-product of target lesion(s) | ||

| PD | >25% increase from maximum response of target lesion(s) | ||

| Response Evaluation Criteria for Solid Tumors Guidelines (RECIST) [9] | CR | Disappearance of all target lesions | |

| PR | ≥30% decrease in maximum diameter of target lesion (s) | ||

| SD | <30% decrease to ≤20% increase in maximum diameter of target lesion(s) | ||

| PD | >20% increase from maximum response of target lesion(s) | ||

| Necrosis Criteria | Modified Response Evaluation Criteria for Solid Tumors Guidelines (mRECIST) [10] | CR | Disappearance of any intratumoral arterial enhancement in all target lesions |

| PR | ≥30% decrease in the sum of maximum diameters of enhancing tissue in target lesion(s) | ||

| SD | <30% decrease to ≤20% increase in the sum of maximum diameters of enhancing tissue in target lesion(s) | ||

| PD | >20% increase in amount of enhancing tissue in target lesion(s) | ||

| European Association for the Study of the Liver Guidelines (EASLmeas and EASLest) [7, 28] | CR | Disappearance of any intratumoral arterial enhancement in all target lesions | |

| PR | ≥50% decrease in amount of enhancing tissue in target lesion(s) | ||

| SD | <50% decrease in amount of enhancing tissue in target lesion(s) | ||

| PD | >25% increase in amount of enhancing tissue in target lesion(s) and/or new enhancement in previously treated lesions |

CR = complete response, PR = partial response, SD = stable disease, PD = progressive disease.

Statistical Analysis

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables were used to examine demographic characteristic differences between patients who underwent embolization with Bead Block™ microspheres or with doxorubicin-loaded LC Bead™.

Weighted kappa statistics with quadratic weights were used to assess agreement with regard to the four response categories (CR, PR, SD and PD) between two different response criteria at each follow-up scan for each reader [25]. Light’s kappa based on weighted kappa with quadratic weights was calculated to assess agreement between 4 readers. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the kappa was estimated using bootstrapping with 2000 repetitions.

To further assess EASLest and EASLmeas, because of the observed bimodal distribution we first reported the percent CR by all 4 readers by both EASL assessments for each reader; for the remaining patients, we evaluated agreement on percent change by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). A logarithm transformation was applied when calculating the ICC due to the skewness of the data. Kappa (κ) and ICC values were interpreted as follows: 0.00–0.20, slight agreement; 0.21–0.40, fair agreement; 0.41–0.60, moderate agreement; 0.61–0.80, substantial agreement; and 0.81–1.00, excellent agreement [26].

Statistical analyses were performed using the software packages SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R version 2.13 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

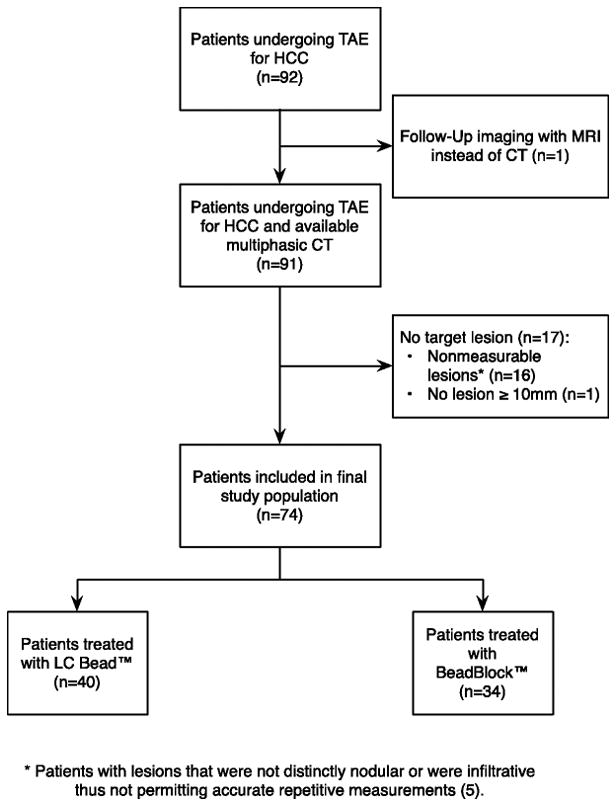

Of the 92 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria, 17 were excluded from our retrospective analysis because the target lesion on the baseline CTs did not meet mRECIST criteria [10, 11], and one was excluded because follow-up imaging was performed by MRI instead of CT (Figure 1). The demographic characteristics of the 74 patients included in the study are summarized in Table 2. The mean time interval between transarterial embolization and 1st FU was 18.1±4.9 days (range, 9–46 days). Seventy of the 74 patients (95%) underwent a 2nd FU at a mean of 87.8±20.1 days (range, 62–183 days) after transarterial embolization. Of the 4 patients who did not have a 2nd FU, one was taken off protocol upon request, one demonstrated disease progression, one died before the 2nd FU, and one had not yet had the 2nd FU at the time of data analysis.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient selection. TAE=transarterial embolization; HCC=hepatocellular carcinoma

* Patients with lesions that were not distinctly nodular or were infiltrative thus not permitting accurate repetitive measurements (5).

Table 2.

Patient demographics

| All patients (n=74) | Patients treated with LC Bead™ (n=40) | Patients treated with BeadBlock™ (n=34) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years); median (range) | 67 (29–87) | 67 (29–86) | 68 (50–87) | 0.470 |

| Gender | >0.999 | |||

| Male | 60 (81) | 32 (80) | 28 (82) | |

| Female | 14(19) | 8 (20) | 6 (18) | |

| Liver Disease | >0.999 | |||

| Hepatitis B virus | 15 (20) | 8 (20) | 7 (21) | |

| Hepatitis C virus | 24 (33) | 13 (33) | 11 (32) | |

| Other | 35 (47) | 19 (47) | 16 (47) | |

| Child-Pugh Class | 0.286 | |||

| A | 65 (88) | 37 (92) | 28 (82) | |

| B | 9 (12) | 3 (8) | 6 (18) | |

| Serum α-fetoprotein; median (range) | 23.9 (1.7– 51122.8) | 31.4 (1.7– 22506.2) | 18.9 (1.7– 51122.8) | 0.276 |

| ≤ 200 ng/ml | 52 (71) | 28 (70) | 24 (71) | >0.999 |

| > 200 ng/ml | 21 (28) | 11 (28) | 10 (29) | |

| unknown | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Total number of lesions; median (range) | 2 (1–6) | 2 (1–6) | 1.9 (1–4) | 0.723 |

| Distribution of lesions | >0.999 | |||

| Solitary | 36 (49) | 19 (48) | 17 (50) | |

| Multifocal | 38 (51) | 21 (52) | 17 (50) | |

| Lesions only in left liver | 16 (21) | 9 (22) | 7 (21) | |

| Lesions only in right liver | 39 (53) | 20 (50) | 19 (56) | |

| Lesions in both liver lobes | 19 (26) | 11 (28) | 8 (23) | |

| Number of follow up CTs | >0.999 | |||

| 1 | 74 (100) | 40 (54) | 34 (46) | |

| 2 | 70 (95) | 37 (93) | 33 (97) |

Unknown serum α-fetoprotein was not included in the test.

Interreader agreement for WHO, RECIST, mRECIST and EASL criteria

Table 3 shows that for all criteria except the WHO criteria, interreader agreement in categorizing response was substantial, with κ-values ranging from 0.631 to 0.780. For WHO criteria, interreader agreement was moderate at 1st FU (κ=0.578) and substantial at 2nd FU (κ=0.716). There were no significant differences in the interreader agreement levels of the various criteria, and confidence intervals of κ-values overlapped for all criteria assessed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Inter- and Inter-test Agreement for Treatment Response (CR, PR, SD, PD)

| Interreader agreement | ||

|---|---|---|

| Interreader agreement; weighted kappa (95%CI) | ||

| 1st FU (n=74) | 2nd FU (n=70) | |

| WHO | 0.578 (0.443, 0.713) | 0.716 (0.589, 0.822) |

| RECIST | 0.631 (0.442, 0.801) | 0.759 (0.644, 0.861) |

| mRECIST | 0.678 (0.562, 0.774) | 0.780 (0.697, 0.855) |

| EASLmeas | 0.700 (0.573, 0.808) | 0.765 (0.669, 0.862) |

| EASLest | 0.698 (0.567, 0.811) | 0.746 (0.646, 0.828) |

| Inter-test agreement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-test agreement between criteria; weighted kappa (95%CI) | ||||

| 1st FU (n=74) | ||||

| Reader 1 | Reader 2 | Reader 3 | Reader 4 | |

| WHO vs RECIST | 0.726 (0.455, 0.903) | 0.799 (0.554, 0.938) | 0.638 (0.469, 0.790) | 0.610 (0.372, 0.783) |

| EASLmeas vs EASLest | 0.910 (0.833, 0.966) | 0.912 (0.756, 0.975) | 0.918 (0.854, 0.967) | 0.899 (0.809, 0.957) |

| 2nd FU (n=70) | ||||

| Reader 1 | Reader 2 | Reader 3 | Reader 4 | |

| WHO vs RECIST | 0.776 (0.612, 0.896) | 0.782 (0.610, 0.906) | 0.741 (0.587, 0.853) | 0.655 (0.485, 0.801) |

| EASLmeas vs EASLest | 0.844 (0.723, 0.920) | 0.877 (0.809, 0.929) | 0.843 (0.775, 0.909) | 0.843 (0.752, 0.909) |

CR = complete response; PR = partial response; SD = stable disease; PD = progressive disease.

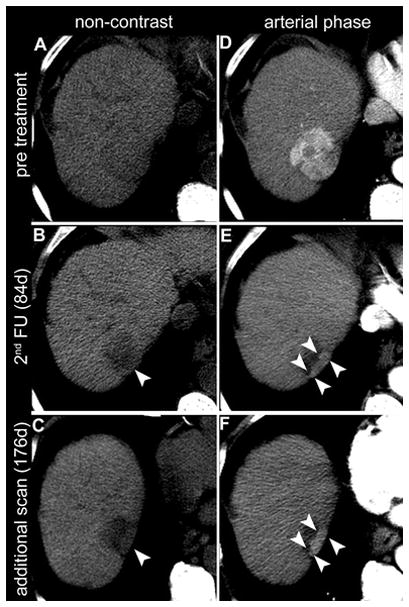

Agreement between the 4 readers regarding treatment response category (CR, PR, SD, PD) was substantial for EASLmeas (κ=0.700 and κ=0.765 for 1st and 2nd FU, respectively) as well as for EASLest (κ=0.698 and κ=0.746 for 1st and 2nd FU, respectively) (Table 3, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Non-contrast CT (A–C) and CT in arterial phase (D–F) of a 73-year-old male with HCC in liver segment VII (arrow in D). In the 2nd follow-up CT (B,E), 84 days after locoregional treatment, the area marked with arrowheads was judged by one reader as normal enhancing liver parenchyma, resulting in a response evaluation of CR (complete response). Another reader judged the same area (arrowheads in B and E) as remaining tumour tissue, resulting in a response evaluation of PR (partial response). The discrepancy in response evaluation was present for EASLmeas as well as EASLest. A further available control scan 176 days after transarterial embolization (C,F) more clearly depicts the area as remaining enhancing tumour tissue (arrowheads in C and F).

Inter-test agreement between EASLmeas and EASLest

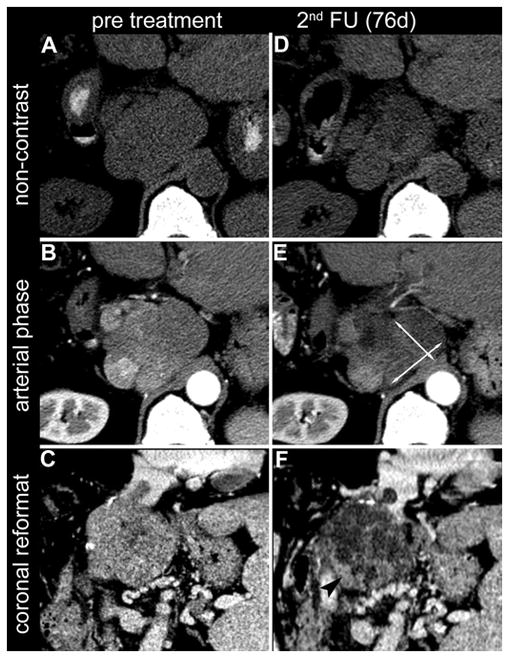

Inter-test agreement regarding treatment response category (CR, PR, SD, PD) between EASLmeas and EASLest was excellent for all 4 readers at both FU time points (Table 3). Inter-test agreement was higher between EASLmeas and EASLest than between WHO and RECIST (Table 3, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Axial slices of non-contrast CT (A, D) and arterial phase CT (B, E) of a 66-year-old male with HCC in liver segment I. In the 2nd follow-up CT (B,E), 76 days after locoregional treatment, the bidimensional measurement of the remaining enhancing tumour tissue (EASLmeas; arrows in E) indicated a decrease of 20% as compared to the baseline scan and therefore resulted in a response evaluation of SD (stable disease). By visual estimation (EASLest), the same reader judged the reduction in enhancing tumour tissue to be 70%, resulting in a response evaluation of PR (partial response). This visual estimation of reduced enhancing tumour tissue (arrowhead in F) is supported by the coronal reconstructions of the tumour shown on the baseline CT (C) and at 2nd follow up (F).

Quantitative assessment of necrosis

Interreader Agreement

Twenty-eight and 23 patients were deemed to have a CR by all 4 readers at 1st and 2nd FU, respectively. In the remaining patients who were deemed to have a non-complete response, the ICC between continuous measurements of enhancement change was 0.769 for 1st FU and 0.878 for 2nd FU for EASLmeas and 0.756 for 1st FU and 0.838 for 2nd FU for EASLestt (Table 4).

Table 4.

Interreader and inter-test agreement in quantitative assessment of necrosis

| Interreader agreement

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st FU (n=74) | 2nd FU (n=70) | |||

| EASLmeas | EASLest | EASLmeas | EASLest | |

| Interreader ICC on non-CR* | 0.769 | 0.756 | 0.878 | 0.838 |

|

| ||||

| Inter-test Agreement between EASLmeas and EASLest | ||||

|

| ||||

| 1st FU (n=74) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Reader 1 | Reader 2 | Reader 3 | Reader 4 | |

|

| ||||

| Inter-test ICC on non-CR** | 0.762 | 0.690 | 0.694 | 0.775 |

|

| ||||

| 2nd FU (n=70) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Reader 1 | Reader 2 | Reader 3 | Reader 4 | |

|

| ||||

| Inter-test ICC on non-CR** | 0.729 | 0.670 | 0.730 | 0.759 |

CR=complete response; CI=confidence interval; ICC=intraclass correlation coefficient

Agreement on log transformed EASL assessments;

ICC was calculated only for the non-CR patients on CT as judged by all readers.

Inter-test Agreement

The number of patients to have CR by both methods, EASLmeas and EASLest, were 36, 45, 37 and 32, respectively for readers 1 to 4 at 1st FU and 31, 38, 28 and 26 at 2nd FU. Inter-test agreement on the quantitative change of enhancement within lesions between EASLmeas and EASLest was substantial in the patients who were deemed to have a non-complete response by both measures. At 1st FU, the ICC was 0.762 for reader 1, 0.690 for reader 2, 0.694 for reader 3 and 0.775 for reader 4. At 2nd FU, the corresponding ICCs were 0.729, 0.670, 0.730 and 0.759 (Table 5).

Discussion

We evaluated interreader agreement in applying size- and necrosis-based response assessment criteria in patients who underwent transarterial embolization for HCC. In addition, we evaluated interreader and inter-test agreement between two different methods of applying the EASL criteria – one in which the change in enhancement was estimated visually (as EASLest), and one in which the change was measured bidimensionally (as EASLmeas). Agreement between the four readers in categorizing response was substantial for both methods of applying the EASL criteria. Furthermore, inter-test agreement between EASLest and EASLmeas was excellent at two follow-up points.

Radiologic evaluation plays a central role in assessing the response to transarterial embolization in patients with HCC. Various response assessment criteria have been proposed [7–10] and different criteria are being applied in different institutions. The variety of different criteria has led to efforts for instance by the American College of Radiology (ACR) Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System (LI-RADS) to create a standardized method to assess tumour response after transarterial embolization of HCC (Claude Sirlin, chair of ACR LI-RADS committee, personal communication). In recent studies, classifications of response based on radiologic criteria have been found to correlate significantly with outcomes [11, 27] or histopathologic findings [12, 28–31]. In patients with HCC, transarterial embolization techniques have been shown to cause necrosis even when tumour size has not yet decreased; therefore, after embolization, necrosis-based criteria may predict outcomes earlier than size-based criteria [11, 12, 28, 30]. However, in all these studies—in contrast to clinical—practice the classifications were based on the consensus of two or more readers [22].

One recent study investigating interreader variability of RECIST and WHO criteria in a heterogeneous patient group undergoing various anti-neoplastic treatments demonstrated moderate to substantial agreement, with κ-values of 0.54 and 0.61, respectively [32]. These results are in accordance with our findings regarding these size-based criteria, even though the patient population and treatment methods assessed in our study were quite different. Necrosis-based criteria may reflect tissue changes after transarterial embolization earlier than size-based criteria and therefore allow for earlier assessment of treatment response. While it may be assumed that regions of enhancement are more difficult to define and measure than lesion size and therefore may be less reproducible, our data shows that interreader agreement for necrosis-based criteria were not inferior to size based-criteria.

Unlike RECIST, mRECISTj and WHO guidelines, the EASL guidelines do not precisely state the method by which tumour response should be calculated [7]. As a result, investigators have interpreted the EASL guidelines in various ways, using visual estimation [14, 15], unidimensional [16], bidimensional [11, 17] or volumetric measurements [18–21] to estimate enhancing tissue. In our study, the readers estimated the percentage of enhancing tissue visually and also measured the largest area of tumour enhancement uni- and bidimensionally on one slice; volumetric evaluation was not performed, because it may be hampered in clinical practice by personnel and hardware resources as well as time constraints. The fact that agreement between the two methods EASLmeas and EASLest was excellent for all readers suggests that visual assessment of enhancing tissue is an adequate method to use in clinical practice. Moreover, because it is less time-consuming and less disruptive of the interpretation process, it may be the preferable approach for interpreting the EASL guidelines in clinical practice.

Our study had a number of limitations. First, we were not able to use histopathologic correlation to validate the treatment responses determined with the different response criteria, as our patients did not undergo subsequent resection, transplantation or autopsy after transarterial embolization. Second, our study included patients treated with two different methods of transarterial embolization, and subanalyses of the two groups were not performed because of the limited sample size. However, for assessment of interreader agreement, we assumed that the two different methods of transarterial embolization would not significantly influence our measurements. Third, patients with infiltrating lesions were excluded from analysis, as these lesions are not regarded as measurable according to response assessment guidelines [9, 10]. Fourth, in case of discrepancies in assessment of treatment response between readers, a conclusive decision on the actual treatment response could not reliably be assessed due to the lack of a standard of reference. Finally, we used CT to evaluate treatment response. While MRI may have benefits when lipiodol limits the usefulness of CT [33], in our patient cohort lipiodol was not used and in many institutions CT is the main modality for postoperative follow-up after transarterial embolization and may even be used during the intervention [34].

In summary, this study demonstrates that after transarterial embolization for HCC, there is substantial interreader agreement in applying both size- and necrosis-based response assessment criteria. In addition, it shows that inter-test agreement between visual estimation and bidimensional measurement of enhancing tissue is excellent, which suggests that these two methods can be used interchangeably to evaluate treatment response of HCC after transarterial embolization.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Key points.

Applying EASL criteria, visual estimation and bidimensional measurements show comparable interreader agreement.

EASLmeas and EASLest show substantial interreader agreement for treatment-response in HCC.

Agreement was excellent for EASLmeas and EASLest after TAE of HCC.

Visual estimation of enhancement is adequate to assess treatment-response of HCC.

Acknowledgments

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Richard Kinh Gian Do. The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article. One of the authors, Olivio F. Donati, received funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Swiss Radiological Society. Junting Zheng and Chaya S. Moskowitz kindly provided statistical advice for this manuscript. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (patients) in this study. Methodology: retrospective, cross sectional study, performed at one institution.

References

- 1.Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9319):1734–1739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35(5):1164–1171. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhanasekaran R, Kooby DA, Staley CA, Kauh JS, Khanna V, Kim HS. Comparison of conventional transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and chemoembolization with doxorubicin drug eluting beads (DEB) for unresectable hepatocelluar carcinoma (HCC) Journal of surgical oncology. 2010;101(6):476–480. doi: 10.1002/jso.21522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maluccio MA, Covey AM, Porat LB, et al. Transcatheter arterial embolization with only particles for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology: JVIR. 2008;19(6):862–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Mulcahy MF, et al. Radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using Yttrium-90 microspheres: a comprehensive report of long-term outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(1):52–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sacco R, Bargellini I, Bertini M, et al. Conventional versus doxorubicin-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology: JVIR. 2011;22(11):1545–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, et al. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. Journal of hepatology. 2001;35(3):421–430. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO Handbook for Reporting Results of Cancer Treatment. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(3):205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Seminars in liver disease. 2010;30(1):52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shim JH, Lee HC, Kim SO, et al. Which response criteria best help predict survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma following chemoembolization? A validation study of old and new models. Radiology. 2012;262(2):708–718. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riaz A, Miller FH, Kulik LM, et al. Imaging response in the primary index lesion and clinical outcomes following transarterial locoregional therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(11):1062–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prajapati HJ, Spivey JR, Hanish SI, et al. mRECIST and EASL responses at early time point by contrast-enhanced dynamic MRI predict survival in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) treated by doxorubicin drug-eluting beads transarterial chemoembolization (DEB TACE) Ann Oncol. 2013;24(4):965–973. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forner A, Ayuso C, Varela M, et al. Evaluation of tumor response after locoregional therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma: are response evaluation criteria in solid tumors reliable? Cancer. 2009;115(3):616–623. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamel IR, Liapi E, Reyes DK, Zahurak M, Bluemke DA, Geschwind JF. Unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: serial early vascular and cellular changes after transarterial chemoembolization as detected with MR imaging. Radiology. 2009;250(2):466–473. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2502072222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malagari K, Alexopoulou E, Chatzimichail K, et al. Transcatheter chemoembolization in the treatment of HCC in patients not eligible for curative treatments: midterm results of doxorubicin-loaded DC bead. Abdominal imaging. 2008;33(5):512–519. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9334-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malagari K, Pomoni M, Kelekis A, et al. Prospective randomized comparison of chemoembolization with doxorubicin-eluting beads and bland embolization with BeadBlock for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2010;33(3):541–551. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9750-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin M, Pellerin O, Bhagat N, et al. Quantitative and volumetric European Association for the Study of the Liver and Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors measurements: feasibility of a semiautomated software method to assess tumor response after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology: JVIR. 2012;23(12):1629–1637. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonekamp S, Jolepalem P, Lazo M, Gulsun MA, Kiraly AP, Kamel IR. Hepatocellular carcinoma: response to TACE assessed with semiautomated volumetric and functional analysis of diffusion-weighted and contrast-enhanced MR imaging data. Radiology. 2011;260(3):752–761. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11102330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galizia MS, Tore HG, Chalian H, McCarthy R, Salem R, Yaghmai V. MDCT necrosis quantification in the assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma response to yttrium 90 radioembolization therapy: comparison of two-dimensional and volumetric techniques. Academic radiology. 2012;19(1):48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corona-Villalobos CP, Halappa VG, Geschwind JF, et al. Volumetric assessment of tumour response using functional MR imaging in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with a combination of doxorubicin-eluting beads and sorafenib. European radiology. 2015;25(2):380–390. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3412-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bankier AA, Levine D, Halpern EF, Kressel HY. Consensus interpretation in imaging research: is there a better way? Radiology. 2010;257(1):14–17. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deodhar A, Brody LA, Covey AM, Brown KT, Getrajdman GI. Bland embolization in the treatment of hepatic adenomas: preliminary experience. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology: JVIR. 2011;22(6):795–799. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.02.027. quiz 800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shim JH, Lee HC, Won HJ, et al. Maximum number of target lesions required to measure responses to transarterial chemoembolization using the enhancement criteria in patients with intrahepatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of hepatology. 2012;56(2):406–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The Equivalence of Weighted Kappa and the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient as Measures of Reliability. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1973;33(3):613–619. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Memon K, Kulik L, Lewandowski RJ, et al. Radiographic response to locoregional therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma predicts patient survival times. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):526–535. 535 e521–522. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riaz A, Memon K, Miller FH, et al. Role of the EASL, RECIST, and WHO response guidelines alone or in combination for hepatocellular carcinoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Journal of hepatology. 2011;54(4):695–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bargellini I, Vignali C, Cioni R, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: CT for tumor response after transarterial chemoembolization in patients exceeding Milan criteria--selection parameter for liver transplantation. Radiology. 2010;255(1):289–300. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riaz A, Kulik L, Lewandowski RJ, et al. Radiologic-pathologic correlation of hepatocellular carcinoma treated with internal radiation using yttrium-90 microspheres. Hepatology. 2009;49(4):1185–1193. doi: 10.1002/hep.22747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim BK, Kim KA, Park JY, et al. Prospective comparison of prognostic values of modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours with European Association for the Study of the Liver criteria in hepatocellular carcinoma following chemoembolisation. European journal of cancer. 2013;49(4):826–834. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki C, Torkzad MR, Jacobsson H, et al. Interobserver and intraobserver variability in the response evaluation of cancer therapy according to RECIST and WHO-criteria. Acta oncologica. 2010;49(4):509–514. doi: 10.3109/02841861003705794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kubota K, Hisa N, Nishikawa T, et al. Evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma after treatment with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization: comparison of Lipiodol-CT, power Doppler sonography, and dynamic MRI. Abdominal imaging. 2001;26(2):184–190. doi: 10.1007/s002610000139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loffroy R, Lin M, Yenokyan G, et al. Intraprocedural C-arm dual-phase cone-beam CT: can it be used to predict short-term response to TACE with drug-eluting beads in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma? Radiology. 2013;266(2):636–648. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okuda K, Ohtsuki T, Obata H, et al. Natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma and prognosis in relation to treatment. Study of 850 patients. Cancer. 1985;56(4):918–928. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850815)56:4<918::aid-cncr2820560437>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. American journal of clinical oncology. 1982;5(6):649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria