Abstract

Gay and bisexual boys and men experience social stigma associated with their sexual minority status that can negatively influence health. In addition, experiencing sexual orientation stigma may be linked to a decreased capacity to effectively form and maintain secure attachment relationships with parents, peers and romantic partners across the life-course. We proposed that utilizing a framework that integrates the process by which sexual minority men develop attachment relationships in the context of sexual minority stress can lead to a better understanding of health and well-being among sexual minority men. In addition, we highlight where future research can expand upon the presented model in order to better understand the developmental processes through which attachment and sexual minority stress influences health and health behaviors among sexual minority young adult men.

Keywords: Attachment, Sexual Minority Stress, Health

Introduction

Research from the past 40 years has demonstrated that developing secure attachment relationships is important for health and development across the life course, while attachment insecurity is associated with poor health.1 Although this body of knowledge has been informative in terms of elucidating the importance of forming secure attachment relationships, there has been little research or theory focused on understanding how social stressors associated with being a sexual minority can contribute to attachment functioning and thus, later well being among sexual minority men. Attachment theory stems from the early work of Bowlby 2 who posited that early experiences with a primary caregiver shape health and well-being across the life-course. Bowlby suggested that, based on repeated interactions with a primary caregiver during infancy, infants develop either secure or insecure attachment bonds. When a primary caregiver is consistently responsive in their interactions with a child, the child develops the expectation that their needs will be met. These repeated interactions form an infant’s working model, which guides behaviors, emotions, and cognitions based on early childhood experiences with a primary caregiver.3 In the long term, working models of self, partner, and relationships based on repeated attachment-related interactions with primary caregiver’s, peers, and intimate partners across the life course become internalized as part of one’s cognitions. Experiences of reliable caregiving contribute to a secure attachment orientation, whereas experiences of inconsistent or unavailable caregiving contribute to an insecure attachment style. Both adult attachment avoidance and anxiety have been associated with poor psychosocial health (e.g., poor self-efficacy, the limited ability to receive and give social support, and maladaptive stress and coping processes).3,4

Hazan and Shaver 5 constructed a model of adult attachment that applied the basic constructs of the infant-caregiver model of attachment to intimate relationships. As with childhood attachment, adult attachment style is measured along two dimensions—anxiety and avoidance; people who are low on both of these dimensions of attachment are considered to have a secure adult attachment style. 3,6,7 Individuals who are more secure in their attachment style are able to create and sustain healthy emotional bonds with others. In contrast, researchers suggest that individuals who are more avoidant in their attachment style generally evade intimacy and are uncomfortable with interdependence. 5,8,9 In adult intimate relationships, these individuals tend to be withdrawn from their partner due to their fear of rejection. 10 Such individuals find it difficult to form deep social and emotional bonds with others. Attachment anxiety is also associated with difficulty forming emotional bonds with others. In intimate relationships, these individuals are concerned about their partner’s commitment to the relationship.5,11 Individuals with anxious attachment styles also fear rejection. Yet instead of being withdrawn like individuals with an avoidant attachment style, these individuals participate in emotional dependence behaviors (e.g., “clinging” to an attachment figure) that they use to reinforce the bond. Most studies of adult attachment fail to report sexual orientation status or report results based on samples of all White, heterosexual adults.12 This is problematic because it limits our ability to understand the influence of attachment on health among sexual minority groups who may experience specific social stress associated with being a minority in society. Taken together, although our current frameworks of attachment outline features of how individuals respond to stress, these theoretical frameworks do not adequately account for the impact of social stress associated with being a sexual minority on health and health behaviors.

The specific social stress associated with being a sexual minority is coined sexual minority stress. Meyer13 was one of the first researchers to construct a theoretical model outlining the process by which sexual minority stress is associated with health among sexual minorities. Meyers posits that stress occurs due to objective external events and conditions, which serve as distal stressors. The expectations of stressful events, as well as the vigilance this expectation requires, may lead to the internalization of negative social attitudes and the concealment of one’s sexual orientation, all of which represent stressors that increase mental health concerns. 13 These latter forms of stress are considered proximal stressors and arise in part as a response to distal stressors. Researchers have made important theoretical and empirical contributions exploring the links between sexual minority stress and health disparities. For instance, Hatzenbuehler 14 has discussed how a myriad of social and contextual factors influence the psychological process by which stigma and discrimination are linked to psychopathology. In addition, Denton15 found that expectations of rejection and internalized homophobia predicted severity of physical health symptoms among gay men. Overall, social stigma can have important consequences for health and well-being. In this paper, we will build on existing work to specify the ways that attachment and sexual minority stress intersect to influence health among sexual minority men.

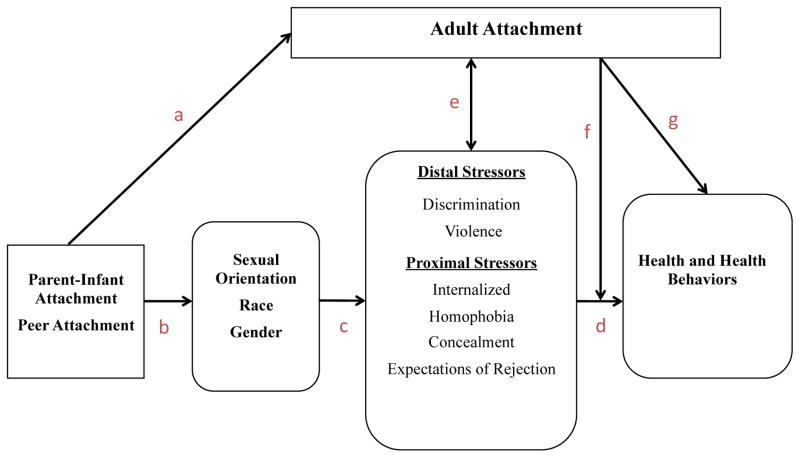

The attachment framework and the sexual minority stress model offer unique yet complimentary perspectives for examining and understanding the health and well-being of sexual minority men. Moreover, making these theoretical and empirical linkages is important for understanding how to address health disparities among sexual minorities. First, we will describe the components of the Integrated Attachment and Sexual Minority Stress (IASMS; see figure 1) Model will first be discussed. Second, we will outline important areas of future research concerning linkages between attachment, sexual minority stress, and health among sexual minority men.

Figure 1.

Integrates Attachment and Sexual Minority Stress Model

Continuity between Attachment in Early Life and Adult Attachment

Attachment in early childhood has implications for health and well-being across the life-course. However, the stability in attachment from childhood into adulthood remains a source of contention among attachment researchers. In the present model, path “a” describes the theoretical and increasingly empirically supported association between attachment in early childhood and attachment in adulthood among sexual minority men.

Hazan, Shaver 5 proposed a model of how attachment behaviors may change from infancy to adulthood using Bowlby’s main characteristics of attachment in early life—safe haven, secure base, and proximity maintenance. The model starts in infancy, the developmental stage where parents provide a safe haven (i.e., being able to rely on an attachment figure for comfort whenever one feels frightened or in danger) and a secure base (i.e., the attachment figure serves as a reliable foundation, thus allowing for the exploration of the world). Attachment proximity maintenance (i.e., feeling secure when the attachment figure is near and being comforted by the attachment figure when distressed) behaviors are also prominent in this developmental stage. From early childhood to early adolescence, peers tend to become more significant attachment figures (i.e., confiding in friends and relying on peer relationships as sources of comfort and support become important). Although parents are never completely eliminated as attachment figures, their roles gradually decrease in centrality as their child transitions into adulthood, where peer and intimate partner relationships become primary sources of social support and attachment. Overall, this model provides a basis for understanding how attachment can transition during different developmental stages, however it provides less information concerning the stability and continuity of attachment. This point is crucial considering that the social stressors that influence the development of sexual minority men may have a profound negative effect on the stability of their attachment style between childhood and adulthood.

Although the empirical research literature has produced inconsistent findings, one of the most compelling theoretical models of attachment stability is the prototype perspective.16 Fraley17 suggests that the prototype perspective may explain the stability of attachment from childhood to adulthood. The prototype perspective suggests that working models associated with relationship formation and the attitudes, feelings, and behaviors associated with those relationships are developed early in the life-course and inform close relationships later in life.18 These working models incorporate experiences in early attachment relationships to guide views, procedural knowledge, and behaviors in future attachment relationships 19,20. Thus, working models are created and adjusted through the life course. Although working models can be changed and adapted, there remains a stable feature underpinning this variation and change.16 This perspective is supported by empirical research. For instance, Waters, Merrick, Treboux, Crowell, Albersheim 21 found that attachment security was moderately stable over an 18 year period. In addition, Waters, Weinfield, Hamilton 22 found that when there was a change in attachment style from infancy to adulthood it was usually do to a dramatic change in the social or family environment.

There has been little research or theory focused on understanding how social stressors can contribute to changes in attachment among sexual minority men between childhood and adulthood.23 In terms of attachment security we suggest that the particular forms and consistency of stressors to which sexual minority men are exposed (e.g., discrimination, rejection by parents or peers) have the potential to overburden their attachment system which, in turn, could contribute to a change in attachment style. More specifically, attachment needs may be more pronounced for sexual minority individuals as a consequence of the increased level of stress from social stigma. Yet this increased level of stress may afford an opportunity for an individual to encode new information from experiences of either receiving or failing to receive social support in times of stress. On the one hand, if an individual experiencing sexual minority stress is able to receive the support of a reliable attachment figure, then they may be able to modify aspects of their working models to become more securely attached. On the other hand, if such an individual does not receive the support of a reliable attachment figure, then they may become less securely attached.

For example, if a sexual minority individual experiences the stress of peer rejection then they may attempt to return to the safe haven of their primary attachment figure. If they are able to get their attachment needs met by their primary attachment figure then the experience of peer rejection may not have as strong of an impact on the individual’s attachment-related working models. However, if the individual were then also rejected by their primary attachment figure then this could compound the stress and negatively influence the working models that the individual developed in childhood. These potential differential outcomes highlight the dynamic nature of attachment development processes across the life course. Such a relationship between environmental stressors and attachment-related coping skills may account for some of the observed changes in attachment style over the life course for sexual minority men. Nevertheless, working models developed in childhood continue to have an influence on the ways that individuals interact in relationships and deal with stress through the life course.

Attachment Early in Life and Sexual Orientation Development

Path “b” of the IASMS Model specifies a dynamic process in which sexual minority youth develop new attachment relationships with peers while also developing their sexual identity. The parallel processes of sexual identity development and the adaptation of attachment characteristics to not only includes parents, but also, peers is a complex process. In this component of the model, we posit that young men’s sexual identity development process is key to understanding the factors that can change attachment style. Our underlying position in formulating this path is that; 1) if young men have a secure attachment style with parents and peers early in life, but are then rejected by their parents or peers due to their sexual orientation, then these young men will become more anxious or avoidant in their attachment style and 2) if young men with a secure attachment style are supported during their sexual identity development process by parents and peers, then they will be able to effectively cope with stress associated with this process and remain more secure into adulthood. Both of these positions are supported by theory and, to a lesser extent, empirical research. We will also discuss the potential of transitioning from an insecure to secure attachment style during the sexual identity development process among young gay men. Although the prototype hypothesis presented in the last section eludes to the continued ability of working models to be adapted over time, there is little empirical research that supports this position.

As specified by Hazan and Shaver’s model of attachment development over the life course, adolescents begin to develop attachment relationships with peers while their parents remain a key attachment figure. During the same time adolescents are beginning to develop their sexual identity. This process may or not be consistent among gay youth. The dynamic attachment and sexual identity development process is best described by Elizur and Mintzer.24 First, the authors outline three primary components of identity development for sexual minority men, including self-definition, self-acceptance, and disclosure. Self-definition refers to the process of creating a sense of individual identity within a broader network of social relations. Self-definition can be complicated by the fact that the relational network can often be a site of prejudice and stress for sexual minority individuals. Self-acceptance refers to the process of working through the internalized negative stigma associated with sexual minority identity. The goal of self-acceptance is to develop a positive personal conception of sexual minority identity. Disclosure refers to the process whereby sexual minority individuals tell others about their sexual identity. Disclosure can take the form of concrete instances of “coming out” as well as ongoing conversations about sexual minority identity.

Second, the authors propose that sexual identity development is fundamentally linked with both attachment and social support.25 Positive experiences associated with sexual identity development are theorized to facilitate the development of secure attachment. These include addressing feelings of confusion about one’s identity, increasing one’s understanding of broader patterns of stigma against sexual minority individuals and how these can become internalized, and finding ways of affirming one’s identity in relation to broader environmental factors. 25 These experiences can in turn increase an individual’s capacity for receiving and providing social support. Secure attachment can also facilitate identity development for young sexual minority men. The caregiving environment influences the development of attachment styles in childhood. Following the prototype model of attachment, the attachment styles developed in childhood continue to have an impact throughout the life course.17 Secure attachment in childhood has been shown to be associated with positive experiences with sexual identity development, including increased openness with friends and romantic partners around sexual identity issues 26,27 and less internalized homophobia.28,29 Insecure attachment has been shown to be associated with negative experiences of sexual identity development, including increased shame, internalized homophobia, and decreased rates of sexual identity disclosure to family members and friends.30

Sexual orientation (or same sex behavior) disclosure is a particularly important component of sexual identity development. Further, this component highlights how sexual identity development can be heavily influenced by attachment during adolescence. Studies have found that sexual minority youth who have a secure attachment style are more open concerning their feelings with peers and intimate partners because they are more comfortable with an attachment figure than individuals who are insecurely attached. 26,27 There have been very few studies conducted that examine the association between attachment and the sexual orientation disclosure process. However, the studies that have been conducted support the notion that young men who are securely attached have an easier time with disclosing or coming out to their friends, family, and peers and thus have less distress than men who are insecurely attached.28 This finding indicates that young men continue to have their primary caregiver as a safe haven while also having friends and/or intimate partners who provide support during the disclosure/coming out process.

Although disclosing may be a less stressful process for young men who initially have a secure attachment style, some young men do experience rejection by parents and/or peers during the sexual identity disclosure process.31 Based on the prospective studies of attachment, rejection by parents could be seen as a key stressor that can change attachment style. For example, in contrast to young men who are more securely attached, one study found that young Black gay and bisexual men with a childhood insecure attachment style many times had either not disclosed to their primary caregiver in adulthood or had been rejected by their primary caregiver after disclosing their sexual orientation.23 This research also suggested that being rejected by an attachment figure during the sexual identity development phase could lead to internalized homophobia (i.e., the internalization of the negative evaluation of sexual minorities), concealment (i.e., the attempt to conceal their sexual orientation), and/or the expectation of being rejected.

Having insecure attachment relationships with parents early in life is associated with having a poorer sexual identity development process.23,24 Young men who are rejected because their parents and peers do not support their sexual identity may have poor attachment relationships and poorer mental health through adulthood.32 There have been few studies that examine the transition from an insecure to secure attachment orientation. Notably, Cook, Heinze, Miller, Zimmerman 33 found that African American youth in late adolescents who transitioned from an insecure to secure attachment style over a 1 year period had less overall depression than adolescents who transitioned from a secure to insecure attachment style. In addition, Lopez, Gormley 34 found that 17% of incoming college freshman changed from an insecure to secure attachment style over a 6-month period. The authors also found that this change was associated with a decrease in depression. Both of these studies report changes in attachment within a short time period and in stressful developmental periods. However, these and similar studies suggest that changes in attachment from insecure to secure can occur in the context of environmental stressor and that this transition is associated with better mental health. In terms of sexual minority young men, it could be the case that while young gay men may experience poor attachment relationships with parents and peers early in life, the sexual identity development process or the introduction of other supportive role models can influence a transition from insecure to secure attachment between childhood and adulthood.

Taken together, in the sexual identity development process, rejection (social and interpersonal) is key to understanding transitions from a secure to insecure attachment style for sexual minority men between childhood and adulthood. The sexual identity development process can be difficult for young gay men due to the social stigma tied to being gay in society. This social stigma can materialize in a number of ways, including rejection by parents and peers, as well as being bullied in school.35 These interpersonal and environmental stressors can have a profound effect on a young man’s working model of self and other. For instance, if a young gay man is more securely attached, but experiences either distal or proximal stressor’s based on his sexual orientation that change his ability to seek comfort from an attachment figure, he may transition to an avoidant or anxious attachment style. In contrast, young sexual minority men who were supported in their sexual orientation development process may continue to be secure because receiving social support from friends and parents reinforces their current working models of self and other. Lastly, it is less clear the particular ways in which young gay men may transition from being more anxious or avoidant in their attachment style to being more secure. We propose that for young men who are more insecurely attached in childhood, having intensive social support from peers, caregivers, and/or additional “pseudo attachment figures, ” may allow for the incorporation of secure attachment-related strategies which in turn influence the transition from an insecure childhood attachment style to a secure adult attachment style. We believe that this can occur even in the context of social stigma and discrimination.

Sexual Orientation, Distal, and Proximal Stressors, and Health and Health Behaviors

Paths “c & d” specify the path by which occupying a marginalized sexual identity is associated with health and health behaviors via distal and proximal stress among sexual minority men. Increased levels of mental health problems in sexual minority men are usually understood as a consequence of the social stigma associated with same-sex sexuality.36 Social stigma refers to forms of negative valuation ascribed to an identity that are communicated through social interactions. Social stigma can be experienced both interpersonally (i.e., through relationships and social interactions) and institutionally (i.e., through discrimination codified in structures which may influence rights or access to resources). For sexual minority individuals, interpersonal experiences might include rejection by parents and peers and experiences of institutional discrimination might include barriers related to not being afforded equal rights in society (e.g. the ability to adopt a child).

Researchers studying attachment among sexual minorities have specifically addressed the role of parental and peer rejection because it is associated with later poor mental health. Even before the development of a sexual orientation, rejection based on gender non-conformity can have a deep negative effect on attachment among adolescent boys.32 Indeed, Landolt, Bartholomew, Saffrey, Oram, Perlman 32 found that gender nonconformity in childhood was associated with parental and peer rejection, and that this rejection was associated with increased attachment insecurity. Further, Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Starks 36 distinguish these two domains of social stigma and point out that little research has focused on the interaction between the two domains. Moreover, the researchers note that experiences with institutional and interpersonal forms of stigma can influence the levels of rejection sensitivity (i.e., the tendency to attend to environmental stimuli that may indicate the threat of being rejected) among sexual minority men, which can, in turn, negatively impact stress coping skills and health behaviors (e.g., substance use; Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Starks 36).

Further, forms of social stigma can be considered distal stressors that can have a negative impact on health outcomes for sexual minorities. Indeed, Lick, Durso, Johnson 37 suggest that minority stress accounts in large part for the notable mental and physical health disparities experienced by sexual minorities. The authors argue that the path between sexual minority stress and health disparities involves a number of intermediate processes. 37 In particular, stressors in the environment associated with social stigma (i.e., distal stressors) are perceived and appraised by sexual minority individuals. This appraisal process is characterized by both psychological responses to stress and physiological responses to stress. Psychological responses to stress may include psychological distress manifesting in symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. Physiological responses to stress can include dysregulation in the HPA axis and the immune system. Both psychological and physiological responses to stress can, in turn, influence the health behaviors in which sexual minority men engage.

The Mutually Reinforcing Association between Adult Attachment and Proximal and Distal Stressors

Path “e” specifies the mutually reinforcing association between adult attachment and social stress from being a sexual minority man. In adulthood, experiences of social stigma due to being a sexual minority man in society can be fundamentally different than experiences of social stigma in childhood. For instance, sexual minority men interact with institutions (e.g. college, corporate jobs, etc.) that have discriminatory social policies (e.g. the inability to adopt children). Based on the unique experiences that adult sexual minority men face, we contend that adult attachment can both shape minority stress experiences among sexual minority men in adulthood, while also being shaped by these experiences. In this section we will; 1) generally review the research literature supporting this bidirectional association and 2) discuss examples of the way in which this bidirectional association may function in the lives of sexual minority men.

Adult attachment style can influence how sexual minority men perceive minority stress. For instance, individual who have an anxious adult attachment style are more likely to perceive a stressor as being very harmful and detrimental to their well-being. This idea is support by a study by Zakalik, Wei 38 who found that discrimination partially mediated the association between adult attachment anxiety and depression in a sample of gay men. This finding suggests that gay men who were more anxiously attached may be more sensitive to rejection based on sexual orientation discrimination than gay men who were less anxious in their adult attachment style.

Distal and proximal stressors may influence adult attachment style among sexual minority men. According to the prototype perspective, working models of self and other can continually be adapted across the life-course. This suggests that adult attachment style can be altered based on interpersonal or environmental factors. We contend that experiences with proximal and distal stressors can influence the adaptation of working models of self and other among sexual minority men. For instance, a sexual minority man who has a secure attachment style and is victimized based on his sexual orientation could transition to a more insecure attachment style. Research literature suggesting that experiencing a significant traumatic event can change an individual’s attachment style supports this notion. In contrast, a sexual minority man who has an insecure attachment style may experience a dramatic decrease in being bullied because he moved to community more accepting of his sexual identity.

Adult Attachment as a Moderator of the Association between Stress and Health

Just as the ability to develop and maintain close relationships bears on the navigation of the sexual identity development process for sexual minority men, the ability to develop and maintain close relationships also bears on the mechanisms by which minority stress is related to physical and mental health outcomes. In line with existing research, our Integrated Model of Attachment and Sexual Minority Stress suggests that secure adult attachment can serve as a buffer against the adverse effects of sexual minority stress. At the same time, this implies that individuals who have difficulty in developing and maintaining close relationships are more at risk for negative physical and mental health outcomes. By looking at the association between adult attachment and stress coping strategies one can begin to see why this may occur.

Attachment in adulthood is associated with different emotion regulation and stress coping strategies. The link between attachment and emotion regulation has been a component of attachment theory from its inception.39 Early attachment theorists suggested that secure adult attachment was associated with particular emotion regulation and coping strategies that were learned from interactions with primary caregivers.40 Secure attachment is thought to be associated with the ability to effectively express and communicate emotions so that attachment needs are met. As such, individuals with a secure attachment style are better equipped to regulate their emotions and cope with stress by being able to negotiate positive relationship interactions. In this way, supportive relationships are thought to moderate the effects of stress.

Insecure attachment is thought to be associated with increased emotional expression and reactivity (i.e., hyper-activation) for anxious attachment and decreased emotional expression (i.e., deactivation) for avoidant attachment. Researchers have indeed found evidence that anxious attachment is associated with hyper-activating emotion regulation strategies and avoidant attachment is associated with deactivating emotion regulation. 41 While these emotion regulation strategies are initially adaptive to the caregiving environment, they can become maladaptive in adolescence and adulthood as the foci of attachment behavior shift from parents to friends and romantic partners.

Adult Attachment and Health

Path “f” distinguishes the primary association between adult attachment and health and health behaviors among sexual minority men. Much of the research literature in this area has focused on samples of mostly White heterosexual individuals, and rare include sexual minority populations. However, there is a small body of work examining the associations between attachment and mental health among sexual minority men. Further, there are a few studies that examine the association between attachment and risk behaviors among sexual minority men. In this section we will review this literature broadly while also indicating key studies that specifically examine the association between attachment and health among sexual minority men.

Attachment researchers have found that attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety are associated with poor physical health.42–44 For instance, Maunder, Hunter, and Lance43 found that attachment anxiety and avoidance were associated with general symptoms of physical illness and poor sleep quality. In addition, McWillimas and Baliey44 found that attachment anxiety was associated with stroke, heart attack, high blood pressure and other cardiovascular dysfunction, while attachment avoidance was associated with headaches or other chronic pain and allergies. In terms of adolescence, one study found that more attachment anxiety was marginally associated with increases in body fat over a 3-year period.45

In terms of risk behaviors, researchers have found evidence that adult attachment insecurity is associated with substance use46 and related risk behaviors such as sexual risk.47 Further, researchers have shown that individuals who are more avoidant or anxious in their attachment style are more likely to use alcohol and/or drugs than individuals who are more secure.48 Researchers have shown that the increased likelihood of using drugs among individuals who have an insecure attachment style is often due to the need to cope with daily or event based stressors. 49 The available research conducted with population of sexual minority men suggests that adult attachment insecurity is associated with increased risk behavior. For instance, Starks and collegues50 found that sexual minority men who were more anxious or more avoidant in their attachment style had higher expectations of sex after using substances, which, in turn, was associated with a higher likelihood of drug use. In addition, Starks, Parsons 51 found that gay men who had a more avoidant adult attachment style were more likely to have causal sexual condomless sex partners than gay men who were more secure.

Empirical Research on Individual Differences in Attachment among Sexual Minorities

Researchers are increasing requesting additional empirical research on attachment and health among sexual minority men.23,51 We posit that there are two pressing inquiries that researchers may wish to address. First, researchers should focus on understanding if there are higher rates of attachment insecurity among sexual minority men, and if so, what are the causes of these heightened rates. As we proposed in our model, we believe that there may indeed be higher rates of attachment insecurity that arise during the sexual identity development process. Due to the social stigma tied to occupying a sexual minority identity in society there is a higher probability that sexual minority young men will be rejected from a parent or peer. Although there are a few studies supporting this claim, the work in this area is scant. Thus, future research should focus on addressing this important research question.

Second, researchers may wish to examine the specific developmental timeframe that sexual minority young men who have a sexual attachment style are most vulnerable to experiencing a change in their attachment style. As it stands, our IASMS t provides a general overview of how the attachment and sexual identity development processes adapt as young men age. However, the timeframe and timing of the process is unclear. In the future researchers may wish to further conduct prospective studies that can better specify the developmental stage(s) in which sexual minority men are most vulnerable to a change in attachment style.

The Link between Adult Attachment and Sexual Minority Stress

Though we have discussed theoretical linkages between attachment and sexual minority stress, there are no empirical studies, to our knowledge, that have discussed the mechanisms by which attachment (in childhood and adulthood) is associated with the stress process among sexual minority men. For example, it could be that having a secure attachment relationship with a primary caregiver during infancy and childhood is the primary mechanism promoting the ability to effectively cope with social stigma concerning sexual orientation. However, it could also be that social stigma and discrimination are perceived as a significant stressor that has the ability to change young sexual minority men’s attachment from secure to insecure. Both of these processes could impact subsequent health yet they may affect health differentially. In the future, researchers must focus on better understanding the process by which attachment from infancy through adulthood interacts with sexual minority stress to influence the health and well-being of sexual minority men.

The Link between Childhood Attachment and Adult Attachment

Though we discuss the theoretical links between childhood and adult attachment above, there are very few empirical studies showing a link between childhood and adult attachment.21,52 Researchers who have examined the continuity of attachment style from infancy to adulthood have reported mixed findings. For example, Waters, Merrick, Treboux, Crowell, Albersheim 21 Hamilton 53 and Fraley and colleagues52 found that attachment was relatively stable from childhood to young adulthood, while Weinfield, Sroufe, Egeland 54 found that attachment style changed over time. Changes in attachment style can occur during periods of great stress, although attachment representations are usually thought to be rather stable. 55,56 Studies have shown that when there is a change in attachment style from infancy to adulthood it is usually due to a dramatic change in the social or family environment such as divorce of parents, death of a parent, or an extensive traumatic experience. 22 Thus, because sexual minority men have heightened rates of poor social conditions (e.g. trauma, familial stress), it may be the case that these men are more likely to have changes in their attachment style (e.g., from secure to insecure).57 In the future, Researchers should consider utilizing prospective data to better understand when, and for what reasons, sexual minority men may have a change in their attachment style attachment style during the transition from childhood to adulthood. By isolating the mechanisms by which changes in attachment style occur, this line of research could help create better-informed and therefore more effective clinical interventions.

The Link between Adult Attachment and Physical Health

Though there is a growing body of research demonstrating a link between attachment insecurity and poor physical health, there remains a paucity of research aimed at understanding the pathways by which attachment insecurity is associated with physical health. 58–60 Maunder & Hunter43 found that individuals who are more insecurely attached may have a predisposition to perceive situations as stressful as compared to individuals who are more securely attached. In addition, attachment anxiety is associated with a hyper-activation of the attachment system, which can, in turn, cause rumination concerning stressful events.58 Attachment avoidance is associated with a deactivation of the attachment system, which can, in turn, cause these individuals to distance themselves from stressful experiences. Although attachment avoidance is associated with a deactivation of the attachment system, researchers have suggested that under prolonged conditions of stress there may a breakdown in the attachment system, thereby causing individuals who are more avoidant to look more anxious.3

Further, it is important to explore biopsychological components of these processes, as cognitive and emotional responses to stress are likely associated with particular physiological stress reactions. Individuals who are more insecurely attached may experience physiological responses to stress that can be detrimental to their physical health. When a stressful event occurs, the HPA axis activates which, in turn, starts the stress activation process. Hormones are released into the body that induce the secretion of cortisol, which is a key marker of stress. Scientists believe that cortisol secretion is a significant pathway by which stress can impact health.60 Jaremka, Glaser, Loving, Malarkey, Stowell, Kiecolt-Glaser 58 found that individuals higher on attachment anxiety had higher cortisol production. Similarly, Powers, Pietromonaco, Gunlicks, Sayer 61 found that insecurely attached individuals showed greater cortisol production in response to relationship conflict in comparison to securely attached individuals. Much of the research literature examining the main effects of attachment on physical health has largely ignored the influence of social stress. Also, few studies have looked at how attachment may differentially influence the physical health of sexual minority individuals as compared to heterosexual individuals. Addressing these gaps in the empirical literature could elucidate important biopsychological pathways between attachment and physiological health.

Conclusion

In summary, sexual minority men are at great risk for poor health across the life course. We developed the IASMS Model to provide a framework for understanding how sexual minority male health. In this model we demonstrated that attachment in childhood is related to both transitions to adult attachment orientation and to the sexual identity development process. Attachment is also related to the ways in which sexual minority men experience and cope with distal and proximal stressors throughout the life course. Further, Researchers have also demonstrated that attachment style could be associated with perceptions of stress as well as particular health behaviors. In addition, researchers have shown that stress arising from social stigma is associated with poor health behaviors as well as adverse physical and mental health outcomes for sexual minority men. Models focused on either attachment or sexual minority stress in isolation lack the ability to elucidate the complex interactions between attachment and sexual minority stress across the life course. Overall, we believe that the Integrated Attachment and Sexual Minority Stress Model provides a theoretical framework for understanding how attachment through the life course interacts with the sexual minority stress processes to influence health and health behaviors among sexual minority men. Further, understanding the pathways by which attachment is related to stress, coping, and subsequent poor health vulnerability is key to both addressing some of the limitations of current preventative health interventions and to developing more comprehensive and effective preventative health interventions.

References

- 1.Ravitz P, Maunder R, Hunter J, Sthankiya B, Lancee W. Adult attachment measures: A 25-year review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2010;69:419–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Adult attachment: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: Guilford; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei M, Russell DW, Zakalik RA. Adult Attachment, social self-efficacy, self-disclosure, loneliness, and subsequent depression for freshman college students: A longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:602–614. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hazan C, Shaver PR. Romantic love conceptualization as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;(3):511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR, editors. Self-report measurement of adult romantic attachment: An integrative overview. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]; Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraley RC, Shaver PR. Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Review of General Psychology. 2000;4:132–154. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feeney JA, Noller P. Attachment style and verbal descriptions of romantic partners. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1991;8:187–215. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feeney BC, Kirkpatrick LA. Effects of adult attachment and presence of romantic partners on physiological responses to stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:255–270. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaver PR, Mikulincer M. Attachment-related psychodynamics. Attachment & Human Development. 2002;4:133–161. doi: 10.1080/14616730210154171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feeney JA, Raphael B. Adults attachments and sexuality: Implications for understanding risk behviors for HIV-Infection. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;26:399–407. doi: 10.3109/00048679209072062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magai C, Cohen C, Milburn N, Thorpe B, McPherson R, Peralta D. Attachment styles in older European American and African American adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2001;56:S28–S35. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.1.s28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(5):707. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denton FN. Minority stress and physical health in lesbians, gays, and bisexuals: The mediating role of coping self-efficacy. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Kreutzer T. The fate of early experience following developmental change: Longitudinal approaches to individual adaptation in childhood. Child Development. 1990;61:1363–1373. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraley RC. Attachment stability from infancy to adulthood: Meta-analysis and dynamic modeling of developmental mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6:123–151. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simpson JA, Rholes WS. Attachment and relationships: Milestones and future directions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2010;27:173–180. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grossman KE, Grossman K, Waters E. Attachment from infancy to adulthood. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simpson JA, Collins WA, Tran S, Haydon KC. Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:355–367. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waters E, Merrick S, Treboux D, Crowell J, Albersheim L. Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: A twenty-year longitudinal study. Child Development. 2000;71:684–689. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waters E, Weinfield NS, Hamilton CE. The stability of attachment security from infancy to adolescence and early adulthood: General discussion. Child Development. 2000;71:703–706. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook SH. Psychological Distress, Sexual Risk Behavior, and Attachment Insecurity among Young Adult Black Men who Have Sex with Men (YBMSM) COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elizur Y, Mintzer A. A framework for the formation of gay male identity: Processes associated with adult attachment style and support from family and friends. Arch Sex Behav. 2001;30:143–167. doi: 10.1023/a:1002725217345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elizur Y, Mintzer A. Gay males’ intimate relationship quality: The roles of attachment security, gay identity, social support, and income. Personal Relationships. 2003;10:411–435. [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT, Sinclair KO. Factors associated with parents’ knowledge of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths’ sexual orientation. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2010;6:178–198. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothman EF, Sullivan M, Keyes S, Boehmer U. Parents’ supportive reactions to sexual orientation disclosure associated with better health: Results from a population-based survey of LGB adults in Massachusetts. Journal of Homosexuality. 2012;59:186–200. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2012.648878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jellison WA, McConnell AR. The mediating effects of attitudes toward homosexuality between secure attachment and disclosure outcomes among gay men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2004;46:159–177. doi: 10.1300/j082v46n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherry A. Internalized homophobia and adult attachment: Implications for clinical practice. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2007;44:219–225. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.44.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown JL, Trevethan R. Shame, Internalized Homophobia, Identity Formation, Attachment Style, and the Connection to Relationship Status in Gay Men. Am J Mens Health. 2010;4:267–276. doi: 10.1177/1557988309342002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Ethnic/racial differences in the coming-out process of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: a comparison of sexual identity development over time. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10(3):215–228. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landolt MA, Bartholomew K, Saffrey C, Oram D, Perlman D. Gender nonconformity, childhood rejection, and adult attachment: A study of gay men. Arch Sex Behav. 2004;33:117–128. doi: 10.1023/b:aseb.0000014326.64934.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cook SH, Heinze J, Miller AL, Zimmerman MA. Transitions in friendship attachment is associated with developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms through adulthood among urban adolescents. Journal of Adolecent Health. 2016;58:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.10.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopez FG, Gormley B. Stability and change in adult attachment style over the first-year college transition: Relations to self-confidence, coping, and distress patterns. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2002;49:355–364. [Google Scholar]

- 35.D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;68:361–371. doi: 10.1037/h0080345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Starks TJ. The influence of structural stigma and rejection sensitivity on young sexual minority men’s daily tobacco and alcohol use. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;103:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lick DJ, Durso LE, Johnson KL. Minority stress and physical health among sexual minorities. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8:521–548. doi: 10.1177/1745691613497965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zakalik RA, Wei M. Adult attachment, perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation, and depression in gay males: Examining the mediation and moderation effects. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53:302–313. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, Pereg D. Attachment theory and affect regulation: The dynamics, development, and cognitive consequences of attachment-related strategies. Motivation and Emotion. 2003;27:77–102. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cassidy J. Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:228–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malik S, Wells A, Wittkowski A. Emotion regulation as a mediator in the relationship between attachment and depressive symptomatology: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;172:428–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ciechanowski PS, Walker EA, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Attachment theory: A model for health care utilization and somatization. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64:660–667. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000021948.90613.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maunder RG, Hunter JJ, Lancee WJ. The impact of attachment insecurity and sleep disturbance on symptoms and sick days in hospital-based health-care workers. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2011;70:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McWilliams LA, Bailey SJ. Associations between adult attachment ratings and health conditions: evidence from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Health Psychol. 2010;29(4):446–453. doi: 10.1037/a0020061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Midei AJ, Matthews KA. Social relationships and negative emotional traits are associated with central adiposity and arterial stiffness in healthy adolescents. Health Psychol. 2009;28:347–353. doi: 10.1037/a0014214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Borhani Y. Substance Abuse and Insecure Attachment Styles: A Relational Study. LUX: A Journal of Transdisciplinary Writing and Research from Claremont Graduate University. 2013;2:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bogaert AF, Sadava S. Adult attachment and sexual behavior. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:191–204. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caspers KM, Cadoret RJ, Langbehn D, Yucuis R, Troutman B. Contributions of attachment style and perceived social support to lifetime use of illicit substances. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1007–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNally AM, Palfai TP, Levine RV, Moore BM. Attachment dimensions and drinking-related problems among young adults: The mediational role of coping motives. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1115–1127. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Starks TJ, Millar BM, Tuck AN, Wells BE. The role of sexual expectancies of substance use as a mediator between adult attachment and drug use among gay and bisexual men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Starks TJ, Parsons JT. Adult attachment among partnered gay men: Patterns and associations with sexual relationship quality. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43:107–117. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0224-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fraley RC, Vicary AM, Brumbaugh CC, Roisman GI. Patterns of stability in adult attachment: An empirical test of two models of continuity and change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101:974–992. doi: 10.1037/a0024150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamilton CE. Continuity and discontinuity of attachment from infancy through adolescence. Child Development. 2000;71:690–694. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weinfield NS, Sroufe LA, Egeland B. Attachment from infancy to early adulthood in a high-risk sample: Continuity, discontinuity, and their correlates. Child Development. 2000;71:695–702. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bowlby J. Attachment, communication, and the therapeutic process. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. 1988:137–157. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kobak RR, Hazan C. Attachment in marriage: Effects of security and accuracy of working models. Journal of Personality and social Psychology. 1991;60:861–869. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.60.6.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosario M, Reisner SL, Corliss HL, Wypij D, Frazier AL, Austin SB. Disparities in depressive distress by sexual orientation in emerging adults: The roles of attachment and stress paradigms. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43:901–916. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0129-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jaremka LM, Glaser R, Loving TJ, Malarkey WB, Stowell JR, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Attachment anxiety is linked to alterations in cortisol production and cellular immunity. Psychological Science. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0956797612452571. 0956797612452571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pietromonaco PR, DeBuse CJ, Powers SI. Does attachment get under the skin? Adult romantic attachment and cortisol responses to stress. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22:63–68. doi: 10.1177/0963721412463229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pietromonaco PR, Uchino B, Dunkel Schetter C. Close relationship processes and health: Implications of attachment theory for health and disease. Health Psychol. 2013;32:499–513. doi: 10.1037/a0029349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Powers SI, Pietromonaco PR, Gunlicks M, Sayer A. Dating couples’ attachment styles and patterns of cortisol reactivity and recovery in response to a relationship conflict. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2006;90:613–628. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]