Highlights

-

•

The recognition of intestinal ischemia often occurs too late due to the presence of unspecific symptoms and lack of reliable exams.

-

•

The combination of laparoscopy and UV light and fluorescein dye should be considered as an invaluable procedure for the early diagnosis of acute bowel ischemia.

-

•

ICG can intraoperatively provide more useful information than conventional clinical assessment, mostly in case of a non-diagnostic CT scan.

Abbreviations: TEVAR, Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair; VAC, Vacuum assisted closure; CT, Computed Tomography; ICG, Indocyanine Green; ICU, Intensive Care Unit

Keywords: Intestinal ischemia, Indocyanine green fluorescence angiography, Case report, Laparoscopy

Abstract

Introduction

Acute mesenteric ischemia is the most severe gastrointestinal complication of acute aortic dissection. The timing of diagnosis is of major importance, in fact the recognition of acute mesenteric ischemia often occurs too late due to the presence of unspecific symptoms and lack of reliable exams. Recently, indocyanine green fluorescence angiography has been adopted in order to measure blood perfusion and microcirculation.

Presentation of case

We decided to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy with the support of intra-operative near-infrared indocyanine green fluorescence angiography, in order to detect an initial intestinal ischemia in a 68-year-old patient previously treated with a TEVAR procedure for a type-B aortic dissection. The fluorescence system demonstrated an hypoperfused area in the ascending colon, therefore an ileocholic resection was thus performed. Opening the operatory specimen, the mucosa of the colon appeared totally ischemic, whilst the serosa was normal.

Discussion

When ischemia occurs, the oxygen supply is interrupted, hence the necrosis of the enteral mucosa occurs within 3 h, whilst the necrosis of the full thickness of the bowel wall occurs within 6 h. A diagnosis during these “golden hours” is of major importance for a successful treatment.

Conclusion

The combination of laparoscopy and UV light and fluorescein dye should be considered as an invaluable diagnostic procedure for the diagnosis of early stage acute bowel ischemia which is not visible at instrumental examinations nor with diagnostic laparoscopy.

1. Introduction

Acute mesenteric ischemia is the most severe gastrointestinal complication of acute aortic dissection with a significant mortality rate ranging from 45 to 87%. The timing of the diagnosis is undoubtedly of major importance, in fact the recognition of acute mesenteric ischemia often occurs too late due to the presence of unspecific symptoms and lack of reliable exams [1]. CT scan could be considered as the gold standard for the diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia, although, in case of delayed recognition or non-exhaustive exams, many patients undergo an exploratory laparotomy [2]. With the advent of minimally invasive surgery, diagnostic laparoscopy has taken a leading role as a less invasive alternative to laparotomy for the early diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia, especially if we also consider the possibility to perform it at the bedside.

In patients with intestinal ischemia, the exact assessment of intestinal perfusion is mandatory, in fact all clinical findings of the intestine such as the serosa surface color, pulsation and bleeding from the marginal arteries have been adopted, but all such clinical findings, if based solely on the experience of the surgeon, may be deceptive.

Indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence angiography has been adopted in order to measure blood perfusion and microcirculation during open surgery [3], [4], and, recently, to assess bowel perfusion during laparoscopic colorectal resection [5].

2. Case report

We decided to adopt this technique in order to early detect and treat an intestinal ischemia in a 68-year-old patient, previously treated with a Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair (TEVAR) procedure for a type-B aortic dissection with an intimal flap from the thoracic aorta up to the internal iliac artery (the dissection involved, also, the renal arteries and the superior mesenteric artery).

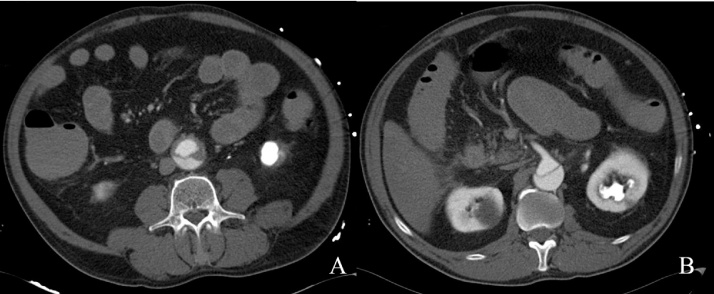

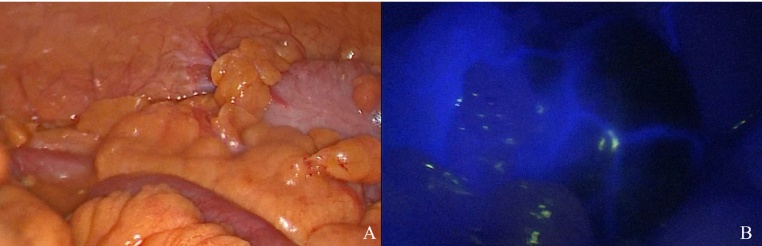

The day following the TEVAR procedure, the patient complained about pain in the abdomen, with the onset of melena. Intra-abdominal pressure, measured via the endo-bladder pressure, was 17 mmHg, and laboratory tests showed an increase in lactates. After a surgical evaluation, a CT scan was performed, but there were no signs of intestinal ischemia and the celiac artery and superior mesenteric artery were pervious (Fig. 1A–B). However, after 2 h the abdomen appeared distended, the diuresis stopped and lactates suddenly increased. Following the informed consent from the patient, we decided to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy with the support of intra-operative near-infrared indocyanine green fluorescence angiography, in order to detect an initial intestinal ischemia. The laparoscopic SPIES system (KARL STORZ GmbH & Co. KG, Tuttlingen, Germany) and high-end full high definition camera system (IMAGE 1 SPIESTM, KARL STORZ) were used. In the operating theater, after the first laparoscopic entry in the abdomen according to the open Hasson technique, an exploratory laparoscopy was performed. The serosa surface color of the bowel was normal and, apparently, no signs of intestinal ischemia were present (Fig. 2A). After exploratory laparoscopy, 25 mg of ICG diluted in distilled water to a concentration of 2.5 mg/ml were injected into a peripheral vein. The fluorescence system demonstrated an hypo-perfused area at the level of the ascending colon (Fig. 2B). An ileocolic resection was thus performed, leaving intact approximately ½ of the ascendant colon. The anastomosis was not immediately performed, according to a damage-control-like strategy, and the abdomen was left open with a VAC system. Opening the operatory specimen, the mucosa of the colon appeared totally ischemic, whilst the serosa was normal (Fig. 3). After 24 h the patient underwent a second look operation: the remaining ascending colon mucosa appeared well perfused, and therefore an ileo-colic anastomosis was performed and the abdominal wall was eventually closed.

Fig. 1.

A–B: CT scan showed no signs of intestinal ischemia. Moreover, the celiac artery and superior mesenteric artery were pervious.

Fig. 2.

A: Intraoperative laparoscopic view of the ascending colon with the standard light. The serosa surface color of the bowel appeared normal. B: The fluorescence system evidenced an hypo-perfused area at the level of the ascending colon. Perfused tissues are, in fact, highlighted with the bright yellow-green dye, whilst the ischemic tissues remain dark. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 3.

Opening the operatory specimen, the mucosa of the colon appeared totally ischemic, whilst the serosa was normal.

3. Discussion

Intestinal ischemia and reperfusion is a challenging and life-threatening clinical issue whereby a delayed diagnosis and treatment definitely contribute to the high in-hospital mortality rate. 70% of the mesenteric blood flow is directed to the mucosa and sub-mucosa layers of the bowel, and 30% to the muscle and serosa layers [6]. When ischemia occurs, the oxygen supply is interrupted, hence the necrosis of the enteral mucosa occurs within 3 h, whilst the necrosis of the full thickness of the bowel wall occurs within 6 h. A diagnosis during these “golden hours” is of major importance for a successful treatment [7]. Oftentimes, diagnostic methods such as CT scan, laboratory tests or clinical findings at diagnostic laparoscopy may be misleading and consequently delay the diagnosis and the subsequent surgical treatment.

Despite diagnostic laparoscopy is an invaluable tool and can be conducted at bedside in ICU patients, it has unfortunately a reduced sensitivity in the early stages of intestinal ischemia, due to the fact that the mucosa can be extensively ischemic while the bowel might still appear normal at external inspection. This drawback can be overcome by using fluorescein-assisted laparoscopy, with which even early stages of ischemia can be identified [8].

ICG is a water-soluble tricarbocyanine dye which, following intravenous administration, binds intensely to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and moderately to low-density lipoprotein (LDL), resulting in very low to zero uptake of the dye in all tissues except for blood [9]. Tissues have two main light absorbers, namely hemoglobin, which absorbs waves below 650 nm, and water, which absorbs infrared light above 900 nm. The main feature of ICG is the capacity of penetrating into tissues and to absorb waves in the near infrared spectrum around 800 nm. Furtermore, it has a short half-time (2.5–3.0 min) and is exclusively secreted by the liver into the bile [10], [11].

When administered intravenously and observed under long-wave UV light, it is possible to see the luminescence of the perfused tissues. This markedly differentiates the perfused tissues highlighted with the bright yellow-green dye, from the ischemic tissues that remain dark.

Intestinal perfusion, in case of early intestinal ischemia, is a difficult parameter to evaluate. Undoubtedly, a near-infrared ICG angiography can intraoperatively provide more useful information than conventional clinical assessment, mostly in case of a non-diagnostic CT scan. Moreover, this method, which comprises the addition of 2 filters to the standard laparoscopic equipment, enables surgeons to make the diagnosis of intestinal ischemia without having to rely on the assistance of other specialists.

4. Conclusion

By means of conclusion, the combination of laparoscopy and UV light and fluorescein dye should be considered as an invaluable diagnostic procedure for the diagnosis of early stage acute bowel ischemia which is not visible at instrumental examinations nor with diagnostic laparoscopy. We expect that the use of this tool to assess bowel perfusion will improve timing in diagnosis of intestinal ischemia, as well as reduce the number of unnecessary small bowel resections and decrease anastomotic leak rates.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

All authors contributed equally to this work: Riccardo Somigli, Gherardo Maltinti and Alessio Giordano performed the operation and collected data, Alessio Giordano obtained the informed consent for procedure and for publication from the patient, Giovanni Alemanno, Riccardo Somigli, Paolo Prosperi and Carlo Bergamini wrote the manuscript, Paolo Prosperi and Andrea Valeri supervised the manuscript.

Guarantor

Carlo Bergamini and Andrea Valeri.

Authorship

Authors assert that the work described has not been published previously, that it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere and that its publication is approved by all authors involved.

Disclosures

Authors certify that there is no actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this article and they state that there are no financial interests or connections, direct or indirect, or other situations that might raise the question of bias in the work reported or the conclusions, implications, or opinions stated − including pertinent commercial or other sources of funding for the individual author(s) or for the associated department(s) or organization(s), personal relationships, or direct academic competition.

Acknowledgement

Prof. Maria Rosaria Buri, Professional Translator/Aiic Conference Interpreter, University of Salento, for English language editing (http://www.mariarosariaburi.it).

References

- 1.Luebke T., Brunkwall J. Outcome of patients with open and endovascular repair in acute complicated type B aortic dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case series and comparative studies. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. (Torino) 2010;51:613–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiiya N., Sawada A., Tanaka E., Tachibana T., Matsuzaki K., Kunihara T. Percutaneous mesenteric stenting followed by laparoscopic exploration for visceral malperfusion in acute type B aortic dissection. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2006;20:521–524. doi: 10.1007/s10016-006-9034-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kisu I., Banno K., Mihara M., Lin L.-Y., Tsuji K., Yanokura M. Indocyanine green fluorescence imaging for evaluation of uterine blood flow in cynomolgus macaque. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iinuma Y., Hirayama Y., Yokoyama N., Otani T., Nitta K., Hashidate H. Intraoperative near-infrared indocyanine green fluorescence angiography (NIR-ICG AG) can predict delayed small bowel stricture after ischemic intestinal injury: report of a case. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2013;48:1123–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boni L., David G., Dionigi G., Rausei S., Cassinotti E., Fingerhut A. Indocyanine green-enhanced fluorescence to assess bowel perfusion during laparoscopic colorectal resection. Surg. Endosc. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4540-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vollmar B., Menger M.D. Intestinal ischemia/reperfusion: microcirculatory pathology and functional consequences.: Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg./Dtsch. Gesellschaft Für Chir. 2011;396:13–29. doi: 10.1007/s00423-010-0727-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurland B., Brandt L.J., Delany H.M. Diagnostic tests for intestinal ischemia. Surg. Clin. North Am. 1992;72:85–105. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)45629-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paral J., Jiri P., Ferko A., Alexander F., Plodr M., Michal P. Laparoscopic diagnostics of acute bowel ischemia using ultraviolet light and fluorescein dye: an experimental study. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2007;17:291–295. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3180dc9376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoneya S., Saito T., Komatsu Y., Koyama I., Takahashi K., Duvoll-Young J. Binding properties of indocyanine green in human blood. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1998;39:1286–1290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alford R., Simpson H.M., Duberman J., Hill G.C., Ogawa M., Regino C. Toxicity of organic fluorophores used in molecular imaging: literature review. Mol. Imaging. 2009;8:341–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimizu S., Kamiike W., Hatanaka N., Yoshida Y., Tagawa K., Miyata M. New method for measuring ICG Rmax with a clearance meter. World J. Surg. 2016;19:113–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00316992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]