Abstract

For three-dimensional tissue engineering scaffolds, the major challenges of hydrogels are poor mechanical integrity and difficulty in handling during implantation. In contrast, electrospun scaffolds provide tunable mechanical properties and high porosity; but, are limited in cell encapsulation. To overcome these limitations, we developed a “hybrid nanosack” by combination of a peptide amphiphile (PA) nanomatrix gel and an electrospun poly (ε-caprolactone) (ePCL) nanofiber sheet with porous crater-like structures. This hybrid nanosack design synergistically possessed the characteristics of both approaches. In this study, the hybrid nanosack was applied to enhance local angiogenesis in the omentum, which is required of tissue engineering scaffolds for graft survival. The ePCL sheet with porous crater-like structures improved cell and blood vessel penetration through the hybrid nanosack. The hybrid nanosack also provided multi-stage fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) release kinetics for stimulating local angiogenesis. The hybrid nanosack was implanted into rat omentum for 14 days and vascularization was analyzed by micro-CT and immunohistochemistry; the data clearly demonstrated that both FGF-2 delivery and porous crater-like structures work synergistically to enhance blood vessel formation within the hybrid nanosack. Therefore, the hybrid nanosack will provide a new strategy for engineering scaffolds to achieve graft survival in the omentum by stimulating local vascularization, thus overcoming the limitations of current strategies.

Keywords: hybrid nanosack, tissue engineering, omentum, crater-like structure, electrospun

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Three dimensional (3-D) tissue engineering scaffolds necessitate blood supply to achieve their biofunctionality. Transplanted cells compete for oxygen and nutrients among themselves as well as with host cells; the survival of implanted cells is limited to the distance of oxygen diffusion (approximately 150~200 μm from a blood vessel) [1]. Thus, angiogenesis is a critical feature which defines the success or failure of constructed 3-D tissues. Besides angiogenesis, a biofunctional tissue engineering scaffold must also meet the following requirements: the scaffold needs to provide a nurturing cellular microenvironment with delivery of therapeutic molecules needed for initial function and stimulation of local angiogenesis; the scaffold should maintain mechanical integrity while simultaneously providing porosity for nutrient transport; finally, the scaffold must be biodegradable to facilitate long-term integration with native tissues. The above criteria are all imperative for the design of an ideal 3-D tissue engineering scaffold.

Currently, there are several approaches for the fabrication of synthetic tissue engineering scaffolds. Hydrogel-based scaffolds have been widely used as a tissue engineering scaffold, because gels can be produced from biocompatible components which facilitate the encapsulation of living cells into a 3-D cell nurturing environment [2–4]. Also, therapeutic molecules can be easily encapsulated within the gel and the controlled release of these molecules is well-established [5–7]. However, hydrogel-based scaffolds generally have poor mechanical properties with low tensile and shear strength. While it is possible to increase the mechanical integrity of hydrogel-based scaffolds via cross-linking, such an increase in mechanical properties comes at the cost of decreasing scaffold degradability and other desirable properties, such as a decrease in cell migratory freedom and impediment of angiogenesis. Furthermore, the hydrogel-based scaffolds are difficult to handle and load into the implant site. Besides hydrogels, electrospinning is also a popular approach in tissue engineering applications, because it allows for the fabrication of nano- or micro- fibers with high surface area to volume ratio and an interconnected porous structure [8, 9]. Notably, highly interconnected electrospun nanofibers structurally mimic the extracellular matrix (ECM) fiber network [10]; thus, this structure can be reasonably well-defined to provide the architecture needed for adhesion, proliferation, and function of various cells, such as skin, bone, tendons, and neurons [11–14]. The mechanical strength is also tunable to match the native tissue properties [9]. While electrospun scaffolds can frequently be made porous, which aids angiogenesis and in transport of nutrients, these scaffolds have a limited capacity to encapsulate cells and to deliver therapeutic molecules. Thus, to produce an ideal synthetic tissue engineering implant, a novel approach is needed for a scaffold that combines the advantages of both hydrogel- and electrospun-based materials. Here, we describe the development and fabrication of a novel hybrid angiogenesis-inducing and cell-nurturing tissue engineered scaffold, called a “hybrid nanosack”. This hybrid nanosack merges electrospinning technology with hydrogel-based controlled release of angiogenic growth factors. The hybrid nanosack consists of a self-assembled peptide amphiphile (PA) nanomatrix gel placed within a porous electrospun poly (ε-caprolactone) (ePCL) nanofiber sheet with crater-like structures (Figure 1). We use the term hybrid “nanosack” because both PA nanomatrix gel and ePCL nanofiber sheet are composed of a basic nano-scale structure: self-assembled PA nanofibers (each fiber length: about 4 nm) and highly interconnected ePCL nanofibers (each fiber diameter: 703 ± 152 nm) respectively; these components interact with cell or tissue graft at nano-scale levels. The PA gel filling the ePCL sack is a novel approach to obtain the synergistic advantages of both materials for stimulation of local angiogenesis with a cell nurturing platform. The hybrid nanosack is designed to provide a multi-stage release of fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) to promote local angiogenesis. FGF-2 is a potent angiogenic growth factor that stimulates vein endothelial cell proliferation and migration in vitro and angiogenesis in vivo [15, 16]. FGF-2 is coated on the outer surface of the ePCL sheet and is also encapsulated within the PA nanomatrix gel. The ePCL sack delivers FGF-2 initially in a burst manner by simple diffusion, which rapidly recruits new blood vessels and promotes initiation of angiogenesis at the implantation area. In addition, the PA nanomatrix gel enables sustained delivery of FGF-2 as the gel slowly degrades, which allows formation of a stable vascular network. Importantly, porous crater-like structures, generated on the ePCL nanofiber sheet by gas foaming/salt leaching technique, enhance blood vessel infiltration and fast vascularization through the hybrid nanosack. PCL is a biodegradable and non-immunogenic polyester, and also provides specific mechanical and elastic properties; thus, it has been widely used for many biomedical applications, such as implantable drug delivery devices, wound dressings, sutures, and fixation devices [17–20]. In addition, degraded PCL products did not show toxic effect and some PCL applications have already been approved by the FDA [21, 22]. The ePCL nanofiber sack with crater-like structures provides suitable mechanical stability for supporting the PA nanomatrix gel. The PA nanomatrix gel can encapsulate tissues as well as therapeutic molecules, and also provide a 3-D extracellular matrix (ECM)-mimicking microenvironment [23, 24]. Therefore, by the combination of these two materials, the hybrid nanosack provides a 3-D nurturing and protective environment for the implanted tissue, multi-stage FGF-2 delivery for enhancing local angiogenesis, and crater-like structures for rapid vascularization. In addition, sack architecture allows the convenient surgical manipulation for implantation by using a simple suturing technique as well as transferability to various implantation sites, such as omentum, subcutaneous, intramuscular, and peritoneal sites.

Figure 1.

Schematic figure of a bio-inspired hybrid nanosack. Creation of a bio-inspired hybrid nanosack for enhanced angiogenesis at the omentum.

One of the major issues of conventional electrospun scaffolds is that they have tightly deposited nanofiber layers with only a small porous network, which limits cell migration or blood vessel penetration through the scaffold [25, 26]. Thus, to overcome this challenge, we used gas foaming/salt leaching technique to create porous spaces within the electrospun scaffold [27]. By this process, porous crater-like structures were generated on the ePCL nanofiber sheet, and they had large pore areas and a loosely packed nanofiber network. These unique features allow cell or blood vessel infiltration throughout the ePCL nanofiber sheet, which improves upon the current challenges of electrospun scaffolds by bestowing a 3-D porous structural aspect. Thus, the ePCL nanofiber sheet with porous crater-like structures appears to be an excellent candidate for the creation of a hybrid nanosack with angiogenic properties.

The PA nanomatrix gel is another component of the hybrid nanosack. PAs are composed of hydrophilic, functional peptide sequences attached to a hydrophobic alkyl chain. Due to their amphiphilic nature, PAs self-assemble into cylindrical micelles for nanomatrix gel formation by addition of multivalent ions or pH change; this enables encapsulation of tissues, growth factors, drugs, etc [4, 23]. Additionally, encapsulated angiogenic growth factors can be released from the nanomatrix gel as it degrades over time. The PA-based nanomatrix gel mimics crucial properties of the natural ECM [23] by incorporated cell adhesive ligands and enzyme-mediated degradation sites. The RGDS sequence (amino acids: arginine, glycine, aspartic acid, serine) was incorporated into the PAs used in this study because it is a cell adhesive ligand present in a variety of ECM molecules such as collagen, laminin, fibronectin, and vitronectin [24]. This sequence interacts with several integrins, specifically α3β1 and αvβ3, and regulates various cellular behaviors. In addition, the matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) sensitive sequence was also included in the PAs as an enzyme-mediated degradation site. The MMP family of enzymes, produced in healthy cells, hydrolyzes most ECM proteins and promotes constant matrix remodeling by the cells [28]. Therefore, an ECM-mimicking PA nanomatrix gel can stimulate natural interactions between tissues and scaffold, and can also be used for various tissue engineering applications such as pancreatic islet transplantation, bone, tooth, and cardiac regeneration, etc [4, 24, 29, 30].

In this study, the hybrid nanosack was applied to the omentum for recruitment of blood vessels to the implantation area. The omentum is a layer of peritoneum that extends from the greater curvature of the stomach and is mostly composed of adipose tissue. The omentum has many advantages for tissue engineering applications. Since the omentum is located in the peritoneal cavity, it has enough space for artificial graft implantation [31, 32]. In addition, the omentum receives a consistent blood supply with many small blood vessels [33]. The omentum also allows ease of surgical access and manipulation. The application of an angiogenic biofunctional platform can be ideal for the implantation of therapeutic cells or tissues, such as pancreatic islets, hepatocytes, and embryonic kidney, into the omentum [34–36]. For example, hepatocyte implantation in the omentum with increased angiogenesis showed great survival and proliferation of implanted hepatocytes [36]. Importantly, the omentum has gained significant attention as a pancreatic islet transplantation site, because it provides a large implantation volume, easy accessibility, and immunological privilege from host rejection of the implanted islets [34, 37]. However, there is still significant islet death in the omentum which is most likely associated with ischemia and inadequate nutrient supply due to incomplete revascularization [38]. Thus, rapid islet revascularization is important to provide sufficient nutrients and oxygen to the implanted islets; this is also essential for the survival of any other implanted tissues in the omentum. As an angiogenic tissue engineering scaffold, the hybrid nanosack is expected to recruit and connect blood vessels from the host to the graft at the omentum by providing multi-stage release of FGF-2 and enhanced porous structures. Besides enhancing vascularization, the hybrid nanosack also prevents the leakage of implanted tissues from the omentum, which is another issue for the utilization of the omentum site [38]. By combining the desirable qualities of hydrogel and electrospun materials, we have developed a new class of tissue scaffold which can be applied to improve outcomes of tissue grafts requiring vascularization in the omentum. Therefore, in this study, we fabricated the hybrid nanosack and tested its feasibility to enhance blood vessel generation within the hybrid nanosack implanted at the omentum using micro-computer tomography (micro-CT) analysis. We demonstrate the hybrid nanosack could lead to enhanced survival of omental tissue grafts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fabrication of an ePCL nanofiber sheet with crater-like structures

A 8.5 w/v% solution of poly (ε-caprolactone) (PCL, Mn: 80,000; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 2, 2, 2-trifluoroethanol (TFE) was prepared. The PCL solution was loaded in a syringe fitted with a 25 gauge blunt-tipped needle. The syringe was placed into a syringe pump (KD Scientific, Holliston, MA) with a set flow rate of 1.0 ml/hr and at a distance of 28 cm from the needle tip to the front plane of an aluminum foil collector (dimensions: 8 cm × 8 cm). Electrospinning was carried out at a voltage of 21 kV using a high-voltage generator (Gamma High-Voltage Research, Ormond Beach, FL) for 2 hours. For the gas foaming/salt leaching procedure, sodium bicarbonate particles (sigma Aldrich) were sieved to sizes between 100 and 200 μm; the sieved particles were introduced through the sheath surrounding the syringe and above the ePCL nanofibers being formed. To control the crater-like structure formation on the surface of the ePCL nanofiber sheet, electrospinning was performed with different amounts of sodium bicarbonate incorporated into the nanofibers (PCL to sodium bicarbonate weight ratios of 1:2, 1:6, 1:8, and 1:12). The total sodium bicarbonate needed for each ratio was measured and divided into 24 installments. Each of the installments was added for 45 seconds in 5 minute intervals during electrospinning. Afterwards, the sodium bicarbonate-containing ePCL nanofiber sheet was immersed in a 50% citric acid solution for 30 minutes to generate gas foam and then in deionized water for 3 days to leach the remaining salts. The deionized water was replaced every day, and the samples were dried at room temperature.

2.2. Morphology characterization of the ePCL nanofiber sheet with crater-like structures

Morphology of the ePCL nanofiber sheet with crater-like structures was analyzed by scanning electron microscope (SEM). The e-PCL nanofiber sheets with and without crater like structures were sputter coated with gold and palladium. QuantaTM 650 FEG (FEI Co.) at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV was used to visualize both sheets. Image J software (National Institute of Health, USA) was used to measure fiber diameters and pore areas within the crater-like structures by analysis of the SEM images (750X magnification) of the ePCL nanofiber sheets. The pore areas were displayed as a polygonal form surrounded by the deposited ePCL nanofibers, and were optimized to threshold the proper fiber layer. In addition, 3-D morphologies of crater like structures were visualized by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining with confocal microscopy.

2.3. HUVEC infiltration test through the ePCL nanofiber sheet with crater-like structures

To test whether crater-like structures allow cell penetration throughout the sheet, a human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) infiltration test was conducted on each PCL:sodium bicarbonate ratio of ePCL nanofiber sheet with crater-like structures (PCL to sodium bicarbonate weight ratios of 1:2, 1:6, 1:8, and 1:12). All sheets were sterilized by soaking in a solution of 70% ethanol and 30% phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 6 hours under sterile condition; then, the sheets were serially diluted in PBS for 3 hours, and finally soaked in PBS for 6 hours. HUVECs were seeded on the ePCL nanofiber sheets with crater-like structures (105 cells/cm2) and cultured. The HUVEC infiltration test was performed in four individual experiments and samples in each condition were collected from each individual experiment. After 4 days of incubation, the sheets were fixed with 10% formalin, embedded in Histoprep embedding medium (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for cryosection. Frozen blocks were sectioned into 40μm-thick slices using a Microm HM 505E cryostat (Instrumedics, IL) and the sections were mounted onto Superfrost/Plus microscope slides (Fisher Scientific). The slides were stained by Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) to display the cellular nuclei and cytoplasm. A Nikon TE 2000-S microscope was used to take images.

2.4. Peptide amphiphile synthesis

The peptide sequence, GTAGLIGQRGDS, was synthesized using standard Fmoc-chemistry on an Advanced Chemtech Apex 396 peptide synthesizer as described previously [4, 23, 39]. The peptide was alkylated at the N-terminus by adding palmitic acid contained in a solution of o-benzotriazole-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluroniumhexafluorophosphate (HBTU), diisopropylethylamine (DIEA), and dimethylformamide (DMF) for 24 hours at room temperature. Then, cleavage and deprotection were performed with a mixture of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), deionized water, triisopropylsilane, and anisole (40:1:1:1) for 3 hours at room temperature. After removing excess TFA, the peptide amphiphile (PA-RGDS) solution was precipitated in cold ether and lyophilized for 2 days. Successful synthesis of the PA was confirmed by matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry.

2.5. Fabrication of the hybrid nanosack

The hybrid nanosack was fabricated by combining a nanomatrix gel (PA-RGDS) and an ePCL nanofiber sheet with crater-like structures. To stimulate angiogenesis, 100 ng of FGF-2 was prepared for each hybrid nanosack; 150 μg of heparin was mixed with FGF-2 to protect FGF-2 from proteolytic cleavage and enhance FGF-2 bioactivity [40–42]. Half of the prepared FGF-2 (50 ng) was encapsulated within the nanomatrix gel and wrapped within an ePCL nanofiber sheet with crater-like structures coated with the other half FGF-2 (50 ng) (total 100 ng of FGF-2 treatment) to create a bio-inspired hybrid nanosack. The FGF-2 treated amount (50 ng on each nanomatrix gel and ePCL sheet) was determined based on FGF-2 activity test (Supplementary Figure 1).

2.6. Assessment of FGF-2 release kinetics from the hybrid nanosack

FGF-2 release kinetics from the hybrid nanosack for 14 days were analyzed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Three different conditions were considered: a) FGF-2 (100 ng) coated on the surface of hybrid nanosack, b) FGF-2 (100 ng) entrapped within the nanomatrix gel, and c) a hybrid nanosack with equally surface-coated (50 ng) and entrapped (50 ng) FGF-2. 150 μg of heparin was also mixed with FGF-2 in each experimental condition before FGF-2 treatment to the hybrid nanosack as described. All samples were placed in 12-well tissue culture plates; at least four samples per each condition were placed in 2 ml of PBS to collect released FGF-2 solutions. At the predetermined time points (1, 4, 8, 11, and 14 days), the samples were collected and replaced with fresh PBS (2 ml) for the next samplings. All samples were stored at −20°C for ELISA specific for FGF-2.

2.7. Implantation of the hybrid nanosack into the omentum

In order to determine whether the hybrid nanosack can enhance local vascularization in the omentum, the hybrid nanosack was implanted into the omentum of male Sprague Dawley rats (280 – 300 g, 8 – 9 weeks) (Figure 5A). There were four hybrid nanosack groups for this study: a) a FGF-2 untreated hybrid nanosack without crater-like structures (n=8), b) a FGF-2 untreated hybrid nanosack with crater-like structures (n=8), c) a FGF-2 (100 ng) treated hybrid nanosack without crater-like structures (n=8), d) a FGF-2 (100 ng) treated hybrid nanosack with crater-like structures (n=8). Under general anesthesia (inhaled isofluorane, 1–4%), the abdominal cavity was opened by a midline laparotomy and the omentum was spread out onto a wet gauze for implanting the FGF-2 treated hybrid nanosack. The hybrid nanosack was wrapped into the omentum and fixed with 7-0 silk sutures. Then, the created omental pouch was placed back into the abdominal cavity. The abdominal wall was closed with 5-0 Prolene sutures and the skin with 4-0 Nylone sutures. After 2 weeks of implantation, newly formed blood vessels around implanted sites was analyzed by the micro-computer tomography (micro-CT). The contrast agent Microfil MV-122 was perfused and allowed to polymerize overnight at 4°C before implant retrieval. Then, the omental pouch containing the implant was excised for micro-CT imaging analysis. Animal experiments were performed with prior approval from University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Figure 5.

Micro-CT image analysis of blood vessel generation within the hybrid nanosack at the rat omentum. (A) Hybrid nanosack implantation in the rat omentum. (B) A hybrid nanosack. (C) 2-D micro-CT image of the implanted hybrid nanosack in the omentum after 2 weeks. Arrows in (C) indicate micro-blood vessel invasion inside the hybrid nanosack. (D) The 3-D reconstructed micro-CT images of blood vessel generation within the hybrid nanosack. (E) The volume and (F) the density of blood vessels generated within the hybrid nanosack. FGF-2: -- crater: -- (Group A: FGF-2 untreated hybrid nanosack without crater-like structures), FGF-2: -- crater: + (Group B: FGF-2 untreated hybrid nanosack with crater-like structures), FGF-2: + crater: -- (Group C: FGF-2 treated hybrid nanosack without crater-like structures), FGF-2: + crater: + (Group D: FGF-2 treated hybrid nanosack with crater-like structures). (Bars show Mean ± Standard Deviation, #p<0.001 vs. Group A and B, *p<0.01 vs. Group C).

2.8. Micro-CT image processing

Micro-CT imaging was conducted using Scanco-40 (SCANCO Medical Co.). After imaging, the individual image slice was converted to DICOM format and processed with a custom program written in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). Briefly, the program filtered the input images to reduce noise, and then automatically segmented the image slices into regions of a) blood vessels, b) implanted pouch, c) extra-pouch fat and d) empty space. The blood vessels were detected by thresholding with an empirically derived value (6200 Hounsfield units), the empty space was separated from the fat region by thresholding at value of 1000 Hounsfield units, and the pouch region was separated from the fat by defining the optimal threshold value for each slice using the Otsu method.

2.9. Histology analysis

Endothelial cell marker (CD31) expression was examined immunohistochemically in order to observe degree of vessel formation in the fixed samples from micro-CT analysis [43]. Serial sections of 5 μm thickness were cut from the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sample blocks and floated onto charged glass slides (Super-Frost Plus, Fisher Scientific). The samples were incubated at 4°C overnight with rabbit polyclonal antibody against CD31 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Peroxidase-conjugated Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) were applied to the sections for 30 minutes at room temperature. Diaminobenzidine (DAB, Scy Tek Laboratories, Logan, UT) was utilized as the chromagen, and Hematoxylin (7211, Richard-Allen Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI) as the counter stain.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Results for all experiments were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical comparisons were performed using ANOVA for multiple comparisons, with Tukey post hoc analysis for parametric data using SPSS 15.0 software. Also, power analysis suggested that eight to ten rats permitted detection of 50% differences in target endpoints.

3. Results and Discussion

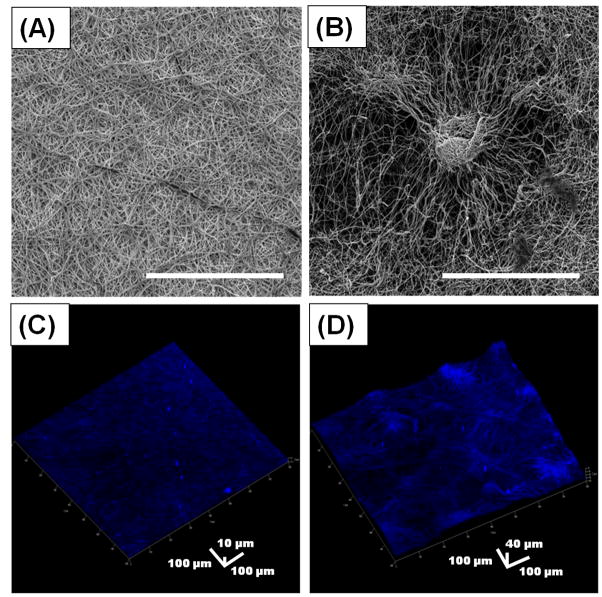

The hybrid nanosack was fabricated by combining a porous ePCL nanofiber sheet with crater-like structures and a PA nanomatrix gel. The hybrid nanosack was designed to enhance angiogenesis of implanted tissue in the omentum by multi-stage delivery of FGF-2 and improved porosity of the sack. As a component of the hybrid nanosack, the ePCL nanofiber sheet was used to envelope and support the PA nanomatrix gel. The ePCL nanofiber sheet produced using conventional electrospinning methods produced a randomly interwoven nanofiber network with uniform fiber morphologies (average fiber diameter: 703 ± 152 nm); however, it had a tightly packed nanofiber network with only superficial, tiny pores, which would limit rapid cell or blood vessel penetration through the sheet (Figure 2A). Thus, to increase porosity, crater-like structures were fabricated on the ePCL nanofiber sheet using gas foaming/salt leaching technique. During electrospinning, sodium bicarbonate particles were incorporated between the deposited ePCL nanofibers. Then, the ePCL nanofiber sheet with the sodium bicarbonate particles was put into a mild acidic solution (citric acid). The reaction between the sodium bicarbonate and citric acid produced CO2 gas bubbles underneath the deposited ePCL nanofibers. The gas bubbles suddenly stretched the ePCL nanofiber network leading to ePCL nanofiber sheet expansion. After the gas bubbles disappeared, the expanded ePCL sheet deflated, but a loosely packed nanofiber network was generated where the sodium bicarbonate particles had been incorporated. This network displayed unique crater-like features on the ePCL nanofiber sheet; each crater size was about 200–400 μm in diameter (Figure 2B). After the gas foaming/salt leaching process, the ePCL nanofibers still showed uniform fiber morphologies with average fiber diameter of 695 ± 201 nm, similar to the ePCL nanofibers that did not undergo the gas foaming/salt leaching process. This indicated that the properties of the ePCL nanofiber itself were not changed by the gas foaming/salt leaching process. The pore areas within the crater-like structures and within the conventional ePCL nanofiber network (control group) were examined by SEM image analysis (Figure 2A and 2B, 750X magnification; Table 1). The total pore area within the craters (41646 ± 3793 μm2) was larger than within the control (8388 ± 1617 μm2); the total analyzed area was the same in both groups (801025 μm2). However, the total pore number of the control group (7938 ± 292) was higher than the crater group (1946 ± 172), which indicated that the control group had many smaller pores compared to the crater group. The control group did not have pore areas larger than 30 μm2; in fact, over 93% (7403 ± 232) of total pores (7938 ± 292) were smaller than 5 μm2. On the contrary, about 19% (370 ± 23) of the total pores (1946 ± 172) in the crater group were larger than 30 μm2; this range of pores (> 30 μm2) covered more than 86% of the total pore area within the craters. Therefore, the pore analysis results demonstrate that the crater group has large total pore area and many bigger pores compared to the conventional ePCL nanofiber network, which may enhance cell or blood vessel penetration through the ePCL sheet. In addition, the 3-D morphologies of the crater-like structures and their loosely packed ePCL nanofiber network were also clearly visualized by confocal microscopy (Figure 2D). However, the conventional ePCL nanofiber sheet presented just a flat 2-D surface with tightly deposited nanofibers (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Characterization of a porous crater-like structure. SEM images of (A) a conventional ePCL nanofiber network and (B) a crater-like structure (Scale bar = 300 μm). 3-D confocal images stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) of (C) a conventional ePCL nanofiber sheet and (D) an ePCL nanofiber sheet with crater-like structures.

Table 1.

Pore area analysis within the crater-like structure and within the conventional ePCL nanofiber network.

| Total pore area | Total number of pores | Pores: 0 – 5 μm2 | 5 – 30 μm2 | 30 – 50 μm2 | 50 – 2300 μm2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crater | 41636 ± 3793 μm2 | 1946 ± 172 (100%) | 1399 ± 138 (72%) | 177 ± 19 (9%) | 116 ± 28 (6%) | 254 ± 38 (13%) |

| Control | 8388 ± 1617 μm2 | 7938 ± 292 (100%) | 7403 ± 232 (93%) | 535 ± 63 (7%) | 0 | 0 |

To control crater-like structure generation on the ePCL nanofiber sheet, we altered the amount of sodium bicarbonate incorporated onto the nanofibers. As more sodium bicarbonate was added, more crater-like structures were generated on the ePCL nanofiber sheet. The amount of incorporated sodium bicarbonate is presented as the weight ratio of PCL to sodium bicarbonate. At the 1:2 (PCL:sodium bicarbonate) ratio, only a few crater-like structures were produced on the ePCL nanofiber sheet (Figure 3C). However, if we increased the sodium bicarbonate amount to the 1:6 ratio, the crater-like structures covered most of surface area of the ePCL nanofiber sheet (Figure 3E). At the 1:8 ratio, the surface area was fully saturated with the crater-like structures and each crater was highly connected with other craters (Figure 3G). When the ratio was beyond over 1:12, the ePCL nanofiber sheet began to separate into multiple layers. In this case, too much sodium bicarbonate incorporation between ePCL nanofibers might prevent the formation of the nanofiber network, leading to layer separation of the ePCL nanofiber sheet. To evaluate fractional internal porosity and pore interconnectivity, human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) infiltration through the crater-like structures was analyzed in each ratio (1:0, 1:2, 1:6, and 1:8) of the ePCL nanofiber sheets. Vein endothelial cell migration from the pre-existed blood vessels is an initial and essential process of angiogenesis [44]. Thus, HUVEC infiltration test is important to estimate whether crater-like structures promote angiogenesis throughout the ePCL nanofiber sheet. After 4 days of culture, most HUVECs were still located on the surface of the conventional 1:0 ratio ePCL sheet (control, no sodium bicarbonate incorporation, thus without craters; depth of infiltration: 27.5 ± 10.41 μm) (Figure 3B). The 1:2 ratio ePCL sheet, which had a few craters on the sheet, showed only slight penetration of HUVECs (depth of infiltration: 50.5 ± 17.5 μm) (Figure 3D). However, the 1:6 ratio ePCL sheet allowed high penetration of HUVECs (depth of infiltration: 251.14 ± 14.93 μm), which indicated that more crater-like structures better promoted HUVEC infiltration through the sheet (Figure 3F). The 1:8 ratio ePCL sheet presented HUVEC infiltration through the entire thickness of the sheet and HUVECs were well distributed within the sheet; depth of infiltration of the 1:8 ratio sheet (273.04 ± 24.5 μm) was slightly increased compared to the 1:6 ratio sheet (Figure 3H). These results demonstrated that interconnected crater-like pores were successfully created within the ePCL sheet, which enhanced cell spreading and distribution through the ePCL sheet. The crater-like structures also allowed better cell penetration compared to the previously reported studies using a conventional salt leaching technique for producing a porous electrospun scaffold, which generated more closed pores and reduced cell penetration through the scaffold; after 3 weeks of culture, depth of cell infiltration was only measured to be 160 μm [45]. The 1:8 ratio ePCL sheet was chosen to fabricate the hybrid nanosack for this study because it had saturated and highly connected craters on the sheet without layer separation and also displayed high penetration (Figure 3I) and distribution of HUVECs through the sheet; thus, it is expected to enhance blood vessel recruitment through the hybrid nanosack.

Figure 3.

Crater-like structure formation on the ePCL nanofiber sheets and HUVEC infiltration test. Crater-like structure formation on each ratio (PCL to sodium bicarbonate weight ratio; 1:0, 1:2, 1:6, and 1:8) of the ePCL nanofiber sheet (A), (C), (E), and (G). HUVEC infiltration through each ratio of the ePCL nanofiber sheet (B), (D), (F), and (H) stained by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). (I) Depth of HUVEC infiltration. (Bars show Mean ± Standard Deviation, #p<0.001 vs. the 1:0 ratio and 1:2 ratio of the ePCL nanofiber sheets) (White scale bar = 500 μm, and black scale bar = 100 μm).

Besides enhanced porosity, the ePCL nanofiber sheet with crater-like structures also plays an important role for protecting the PA nanomatrix gel in the hybrid nanosack. The omentum is a dynamic place in the abdominal cavity, and the PA nanomatrix gel can be easily disrupted in the omentum which leads to the leakage or loss of the gel-encapsulated cells or tissues from the omentum. Thus, the PCL-based electrospun sheet can stably support the structure of the PA nanomatrix gel by enveloping the gel and this sack-like feature also allows tissue retention in the omentum.

The hybrid nanosack provides multi-stage FGF-2 release for stimulation of local angiogenesis. FGF-2 release kinetics from the hybrid nanosack were evaluated for 14 days; three hybrid nanosack groups were designed for this test: (a) FGF-2 only coated on the surface of the hybrid nanosack, (b) FGF-2 only entrapped within the PA nanomatrix gel, and (c) a hybrid nanosack with equal amounts of surface-coated and entrapped FGF-2. Group (a) showed an initial burst release of FGF-2, followed by a plateau: about 91.4% of FGF-2 was released in 1 day, and an additional 0.5% was released after a total 14 days (Figure 4A). Group (b) presented a sustained release of FGF-2: only about 27.8% of FGF-2 was released after 14 days as the PA nanomatrix gel slowly degraded (Figure 4B). Finally, group (c) showed both an initial burst release of FGF-2 (48.3% of total of FGF-2) within 1 day followed by sustained release (20.2% of total FGF-2) over a period of 14 days, which demonstrated multi-stage release of FGF-2 from the hybrid nanosack (Figure 4C). The burst release of FGF-2 resulted from simple diffusion from the surface of the hybrid nanosack; this profile could help to promote initiation of angiogenesis since it allows FGF-2 to be locally accessible quickly. In the previous study, a bolus treatment of angiogenic growth factor successfully stimulated early angiogenesis in the rat omentum [46]. A sustained release of angiogenic growth factor has been shown to result in persistent angiogenic response [5, 43, 47]. Thus, the sustained release of FGF-2 is crucial to keep stimulating angiogenesis and forming a stable vascular network for at least 14 days, the general period to complete angiogenesis after implantation. The hybrid nanosack is able to provide both initial burst and sustained release of FGF-2, which is expected to work together promoting fast recruitment and stable formation of blood vessels in the omentum. In in vivo conditions, it is expected that the PA nanomatrix gel will be further degraded by proteolysis enzymes from invaded blood vessels, because the gel contains MMP-2 sensitive sequence [5, 23]; this will increase the release rate of FGF-2 from the gel as more blood vessels are recruited to the hybrid nanosack.

Figure 4.

Multi-stage release kinetics of FGF-2 from the hybrid nanosack analyzed by ELISA. (A) (■) a FGF-2 surface coated hybrid nanosack. (B) (●) a FGF-2 entrapped within nanomatrix gel. (C) (X) a hybrid nanosack with equal amount of surface-coated and entrapped FGF-2.

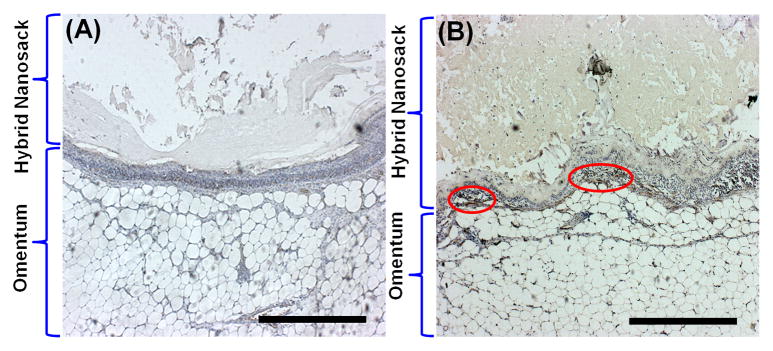

For in vivo experiments, the hybrid nanosack was implanted into the omentum of rats to test whether the hybrid nanosack could enhance local vascularization in the omentum (Figure 5A and 5B). Originally, we implanted a PA nanomatrix gel itself in the rat omentum, but the PA gel was easily disrupted and leaked out of the omentum (not shown in figure). However, the hybrid nanosack was able to support and hold the PA nanomatrix gel and it was also easily implanted in the omentum by using a simple suture technique. Another research group also developed an encapsulation device using a collagen gel immobilized by AN69 membrane (a copolymer of acrylonitrile and sodium methallysulfonate), and the device was implanted in the omentum to enhance local angiogenesis by delivery of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Although the pore size of AN69 membrane was too small (19–41Å) to allow blood vessel penetration through the membrane, the device was able to protect the collagen gel and promote angiogenesis surrounding the device in the omentum [46]. Studies such as this support the feasibility of our hybrid nanosack, and also point to the need for improvements for vascularization through the implanted device. The efficacy of the hybrid nanosack for local angiogenesis was evaluated by a comparison of four hybrid nanosack groups: the hybrid nanosacks (a) without FGF-2 and without crater-like structures, (b) without FGF-2 and with crater-like structures, (c) with FGF-2 (100 ng) and without crater-like structures, and (d) with FGF-2 (100 ng) and with crater-like structures. Two weeks after hybrid nanosack implantation, the presence of blood vessels at the implanted area was analyzed using micro computed tomography (micro-CT). By micro-CT scanning of the hybrid nanosack in the omentum, we obtained the 2-D sectioned images of the implants and observed micro blood vessels surrounding and also within the hybrid nanosack (Figure 5C). Then, the 3-D volumetric images were reconstructed and the blood vessel networks were clearly visualized (Figure 5D). The volume of generated blood vessels within the hybrid nanosack was quantified and compared with each hybrid nanosack group (Figure 5E). Group (d), FGF-2 (100 ng) treated hybrid nanosack with crater-like structure, presented the significantly highest blood vessel generation within the hybrid nanosack (2112 ± 592 mm3) and the blood vessels also thoroughly surrounded the hybrid nanosack. On the contrary, group (a), FGF-2 untreated hybrid nanosack without crater-like structures, showed the lowest blood vessel generation within the hybrid nanosack (227 ± 15 mm3) among all groups and only a few blood vessels surrounded the hybrid nanosack. Both group (b), FGF-2 untreated hybrid nanosack with crater-like structures, and group (c), FGF-2 (100 ng) treated hybrid nanosack without crater-like structures, displayed higher blood vessel generation than group (a), but there was no significant difference between group (b) (587 ± 67 mm3) and (c) (814 ± 411 mm3). A higher dose FGF-2 (500 ng) treated hybrid nanosack with crater-like structures was also implanted in the rat omentum to evaluate the difference of angiogenic potency between two different FGF-2 amounts (not shown in figure). However, there was no significant difference in blood vessel generation within the hybrid nanosack between 100 ng and 500 ng of FGF-2 treated groups (2112 ± 592 mm3 and 1927 ± 340 mm3 respectively). The data showed the same trend when normalized to the volume of the hybrid nanosack (Figure 5F). Group (d) showed the highest vessel density (0.019 ± 0.005) and group (a) presented the lowest vessel density (0.001 ± 0.0002) among all groups. These micro-CT results clearly demonstrated that both FGF-2 delivery and porous crater-like structures synergistically enhanced blood vessel formation within the hybrid nanosack at the omentum. The initial burst release of FGF-2 might rapidly recruit blood vessels to the hybrid nanosack from the surrounding omentum. Then, the recruited blood vessels could easily invade the hybrid nanosack through the porous crater-like structures, and the sustained release of FGF-2 from the PA nanomatrix gel could also help the formation of a stable vascular network within the hybrid nanosack; however, to confirm this, we still need to clearly analyze the effect of multistage FGF-2 release on enhanced angiogenesis in the omentum. Thus, further characterization of initial and long-term angiogenesis processes by multi-stage FGF-2 release will be considered in a future study. Blood vessel generation was also confirmed by immunohistochemistry using CD31 ‘vein endothelial cell marker’ (Figure 6). Group (a), FGF-2 untreated hybrid nanosack without crater-like structures, did not show CD31 stained area or any blood vessel or cell invasion within the hybrid nanosack. Group (b), FGF-2 untreated hybrid nanosack with crater-like structures, still barely presented CD31 stained area, but some cell invasion on the edge of the hybrid nanosack was observed. In group (c), FGF-2 treated hybrid nanosack without crater-like structures, CD31 stained areas were found at the outside of the hybrid nanosack; this indicated that blood vessel generation was promoted by FGF-2 treatment but no craters on the hybrid nanosack limited its generation within the hybrid nanosack. Group (d), FGF-2 treated hybrid nanosack with crater-like structures, showed CD31 stained areas both inside and outside of the hybrid nanosack, indicating blood vessel generation was promoted both surrounding and within the hybrid nanosack. Thus, these results also confirmed that the hybrid nanosack was able to stimulate local blood vessel generation or recruitment in the omentum by the synergistic effects of FGF-2 treatment and crater-like structures.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry analysis with CD31 ‘vein endothelial cell marker’. Immunostaining with CD31 on (A) FGF-2 untreated hybrid nanosack without crater-like structures, (B) FGF-2 untreated hybrid nanosack with crater-like structures, (C) FGF-2 treated hybrid nanosack without crater-like structures, and (D) FGF-2 treated hybrid nanosack with crater-like structures. Arrows and circles are indicated CD31 stained areas. (Scale bar: 500 μm)

FGF-2 is well-known as a strong angiogenic growth factor; it also stimulates and potentiates another angiogenic growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), to form mature large blood vessels [16, 48, 49]. However, one challenge for a FGF-2 delivery system is the maintenance of the bioactivity of FGF-2, because the soluble form of FGF-2 is quickly degraded in vivo [50, 51]. In the hybrid nanosack, FGF-2 was treated with heparin, which interacted with FGF-2 to promote binding to FGF-2 receptor, thereby increasing FGF-2 bioactivity [42, 52]. Heparin also protects FGF-2 from inactivation and helps to preserve the efficacy of FGF-2 even in harsh environments [53]. In addition, encapsulation of FGF-2 within the PA nanomatrix gel and its sustained release from the gel may prolong the angiogenic effect of FGF-2 in the omentum. Sustained FGF-2 delivery systems have been developed as hydrogels, microspheres, and coacervates out of various materials, such as gelatin, alginate, poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG), and poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA); these platforms demonstrated promising results to enhance local angiogenesis at the implanted areas [40, 54–56]. However, low mechanical stability, difficulties in physical manipulation of gel, and leakage issues still need to be improved to increase their efficacy as an angiogenic platform. The hybrid nanosack may overcome these limitations by supporting the PA nanomatrix gel with an electrospun-based scaffold, thus incorporating the advantages of two classes of materials. As an engineered angiogenic scaffold, the hybrid nanosack could be ideal to enhance the efficacy of pancreatic islet transplantation in the omentum. Since rapid islet revascularization is critical for islet survival after implantation, the hybrid nanosack is expected to quickly recruit and generate blood vessels at the implanted islets within the omentum. Enhanced islet revascularization will significantly increase the early islet survival rate in the omentum. Future studies with islets embedded within the hybrid nanosack implanted into the omentum are necessary to confirm the utility of the angiogenesis inducing hybrid nanosack as a platform for nurturing implanted islets to provide a clinical benefit restore islet function.

4. Conclusion

In this study, the hybrid nanosack was developed by combination of a self-assembled PA nanomatrix gel and an ePCL nanofiber sheet with porous crater-like structures. This provided synergistic characteristics of both hydrogel- and electrospun-based materials for stimulation of local angiogenesis with a cell nurturing environment. In addition, the sack-like architecture allowed for convenient surgical manipulation for the application of the hybrid nanosack to the implantation site, especially the omentum. The porous crater-like structures enhanced cell and blood vessel penetration through the ePCL nanofiber sheet, which improved upon the current limitation of a conventional electrospun scaffold with only small superficial pores. To stimulate blood vessel generation, the hybrid nanosack demonstrated deliverance of FGF-2 in a multi-stage manner. Thus, the hybrid nanosack successfully recruited and stimulated blood vessel generation within the sack at the rat omentum by the strategies of multi-stage FGF-2 delivery and improved porosity of the sack. Based on these results, the hybrid nanosack is highly expected to enhance graft vascularization and has strong potential to be an ideal 3-D platform for enhanced graft survival in the omentum.

Supplementary Material

HUVEC proliferation by different concentration of FGF-2 treatment for 3 days. HUVEC proliferation was measured by Cyquant assay (n=5; using one-way ANOVA statistical analysis and Tukey multiple comparison test, *p<0.05 vs. 3 and 500 ng/ml of FGF-2 treated groups, ###p<0.001 vs. 0, 1, and 1000 ng/ml of FGF-2 treated groups).

Statement of Significance.

For three-dimensional tissue engineering scaffolds, the major challenges of hydrogels are poor mechanical integrity and difficulty in handling during implantation. In contrast, electrospun scaffolds provide tunable mechanical properties and high porosity; but, are limited in cell encapsulation. To overcome these limitations, we developed a “hybrid nanosack” by combination of a peptide amphiphile (PA) nanomatrix gel and an electrospun poly (ε-caprolactone) (ePCL) nanofiber sheet with porous crater-like structures.

This design synergistically possessed the characteristics of both approaches. In this study, the hybrid nanosack was applied to enhance local angiogenesis in the omentum, which is required of tissue engineering scaffolds for graft survival. The hybrid nanosack was implanted into rat omentum for 14 days and vascularization was analyzed by micro-CT and immunohistochemistry. We demonstrate that both FGF-2 delivery and porous crater-like structures work synergistically to enhance blood vessel formation within the hybrid nanosack. Therefore, the hybrid nanosack will provide a new strategy for engineering scaffolds to achieve graft survival in the omentum by stimulating local vascularization, thus overcoming the limitations of current strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the efforts of William Monroe and Dr. Robin Foley in SEM imaging lab. We express thanks to the Center for Metabolic Bone Disease histological facility for the use of histology equipments. This study was supported by Alabama EPSCoR Graduate Scholar fellowship funded by NSF. It was also supported by NIBIB (1R03EB017344-01), NSF career award (CBET-0952974), NIDDK (1DP3DK094346-01), NHLBI (1R01HL125391-01), and UAB DRTC Pilot Grant (P30 DK079626).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kaully T, Kaufman-Francis K, Lesman A, Levenberg S. Vascularization--the conduit to viable engineered tissues. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2009;15:159–169. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu J, Marchant RE. Design properties of hydrogel tissue-engineering scaffolds. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2011;8:607–626. doi: 10.1586/erd.11.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phelps EA, Headen DM, Taylor WR, Thule PM, Garcia AJ. Vasculogenic bio-synthetic hydrogel for enhancement of pancreatic islet engraftment and function in type 1 diabetes. Biomaterials. 2013;34:4602–4611. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim DJ, Antipenko SV, Anderson JM, Jaimes KF, Viera L, Stephen BR, Bryant SM, Yancey BD, Hughes KJ, Cui W, Thompson JA, Corbett JA, Jun HW. Enhanced rat islet function and survival in vitro using a biomimetic self-assembled nanomatrix gel. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:399–406. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phelps EA, Landazuri N, Thule PM, Taylor WR, Garcia AJ. Bioartificial matrices for therapeutic vascularization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3323–3328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905447107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoare TR, Kohane DS. Hydrogels in drug delivery: Progress and challenges. Polymer. 2008;49:1993–2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertz A, Wohl-Bruhn S, Miethe S, Tiersch B, Koetz J, Hust M, Bunjes H, Menzel H. Encapsulation of proteins in hydrogel carrier systems for controlled drug delivery: influence of network structure and drug size on release rate. J Biotechnol. 2013;163:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murugan R, Ramakrishna S. Nano-featured scaffolds for tissue engineering: a review of spinning methodologies. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:435–447. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pham QP, Sharma U, Mikos AG. Electrospinning of polymeric nanofibers for tissue engineering applications: a review. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1197–1211. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Apeldoorn AA, Aksenov Y, Stigter M, Hofland I, de Bruijn JD, Koerten HK, Otto C, Greve J, van Blitterswijk CA. Parallel high-resolution confocal Raman SEM analysis of inorganic and organic bone matrix constituents. Journal of the Royal Society, Interface / the Royal Society. 2005;2:39–45. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2004.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumbar SG, Nukavarapu SP, James R, Nair LS, Laurencin CT. Electrospun poly(lactic acid-co-glycolic acid) scaffolds for skin tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4100–4107. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Venugopal JR, El-Turki A, Ramakrishna S, Su B, Lim CT. Electrospun biomimetic nanocomposite nanofibers of hydroxyapatite/chitosan for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4314–4322. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, Xu J, Wang A, Zheng M. Scaffolds for tendon and ligament repair: review of the efficacy of commercial products. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2009;6:61–73. doi: 10.1586/17434440.6.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee Y-S, Livingston Arinzeh T. Electrospun nanofibrous materials for neural tissue engineering. Polymers. 2011;3:413. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marra KG, Defail AJ, Clavijo-Alvarez JA, Badylak SF, Taieb A, Schipper B, Bennett J, Rubin JP. FGF-2 enhances vascularization for adipose tissue engineering. Plast Reconstr Srug. 2008;121:1153–1164. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000305517.93747.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakajima H, Sakakibara Y, Tambara K, Iwakura A, Doi K, Marui A, Ueyama K, Ikeda T, Tabata Y, Komeda M. Therapeutic angiogenesis by the controlled release of basic fibroblast growth factor for ischemic limb and heart injury: toward safety and minimal invasiveness. J Aritif Organs. 2004;7:58–61. doi: 10.1007/s10047-004-0252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker SR, Banerjee S, Bonin K, Guthold M. Determining the mechanical properties of electrospun poly-ε-caprolactone (PCL) nanofibers using AFM and a novel fiber anchoring technique. Materials Science and Engineering: C. 2016;59:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.09.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang D, Hsiao BS, Chu B. Functional electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for biomedical applications. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2007;59:1392–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venugopal J, Ramakrishna S. Biocompatible nanofiber matrices for the engineering of a dermal substitute for skin regeneration. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:847–854. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes CP, Sell SA, Boland ED, Simpson DG, Bowlin GL. Nanofiber technology: designing the next generation of tissue engineering scaffolds. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2007;59:1413–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lo HY, Kuo HT, Huang YY. Application of polycaprolactone as an anti-adhesion biomaterial film. Artif Organs. 2010;34:648–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2009.00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woodruff MA, Hutmacher DW. The return of a forgotten polymer—Polycaprolactone in the 21st century. Prog Polym Sci. 2010;35:1217–1256. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jun HW, Yuwono V, Paramonov SE, Hartgerink JD. Enzyme-mediated degradation of peptide-amphiphile nanofiber networks. Adv Mater. 2005;17:2612–2617. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andukuri A, Kushwaha M, Tambralli A, Anderson JM, Dean DR, Berry JL, Sohn YD, Yoon YS, Brott BC, Jun HW. A hybrid biomimetic nanomatrix composed of electrospun polycaprolactone and bioactive peptide amphiphiles for cardiovascular implants. Acta biomaterialia. 2011;7:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blakeney BA, Tambralli A, Anderson JM, Andukuri A, Lim DJ, Dean DR, Jun HW. Cell in filtration and growth in a low density, uncompressed three-dimensional electrospun nanofibrous scaffold. Biomaterials. 2011;32:1583–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rnjak-Kovacina J, Weiss AS. Increasing the pore size of electrospun scaffolds. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2011;17:365–372. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jun HW, West JL. Endothelialization of microporous YIGSR/PEG-modified polyurethaneurea. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1133–1140. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Visse R, Nagase H. Matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: structure, function, and biochemistry. Circ Res. 2003;92:827–839. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000070112.80711.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaushik SN, Scoffield J, Andukuri A, Alexander GC, Walker T, Kim S, Choi SC, Brott BC, Eleazer PD, Lee JY, Wu H, Childers NK, Jun HW, Parkand JH, Cheon K. Evaluation of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole encapsulated biomimetic nanomatrix gel on enterococcus faecalis and treponema denticola. Biomater Res. 2015;19:9. doi: 10.1186/s40824-015-0032-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ban K, Park HJ, Kim S, Andukuri A, Cho KW, Hwang JW, Cha HJ, Kim SY, Kim WS, Jun HW, Yoon YS. Cell therapy with embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes encapsulated in injectable nanomatrix gel enhances cell engraftment and promotes cardiac repair. ACS nano. 2014;8:10815–10825. doi: 10.1021/nn504617g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Xu P, Chen H. Successful tracheal autotransplantation with two-stage approach using the greater omentum. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:199–202. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)82828-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suh S, Kim J, Shin J, Kil K, Kim K, Kim H, Kim J. Use of omentum as an in vivo cell culture system in tissue engineering. ASAIO journal. 2004;50:464–467. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000138016.83837.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Messineo A, Filler RM, Bahoric B, Smith C, Bahoric A. Successful tracheal autotransplantation with a vascularized omental flap. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26:1296–1300. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(91)90603-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merani S, Toso C, Emamaullee J, Shapiro AM. Optimal implantation site for pancreatic islet transplantation. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1449–1461. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammerman MR. Transplantation of embryonic kidneys. Clin Sci. 2002;103:599–612. doi: 10.1042/cs1030599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee H, Cusick RA, Utsunomiya H, Ma PX, Langer R, Vacanti JP. Effect of implantation site on hepatocytes heterotopically transplanted on biodegradable polymer scaffolds. Tissue Eng. 2003;9:1227–1232. doi: 10.1089/10763270360728134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kin T, Korbutt GS, Rajotte RV. Survival and metabolic function of syngeneic rat islet grafts transplanted in the omental pouch. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:281–285. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Contreras JL. Extrahepatic transplant sites for islet xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2008;15:99–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2008.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson JM, Andukuri A, Lim DJ, Jun HW. Modulating the gelation properties of self-assembling peptide amphiphiles. ACS nano. 2009;3:3447–3454. doi: 10.1021/nn900884n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chu H, Gao J, Chen CW, Huard J, Wang Y. Injectable fibroblast growth factor-2 coacervate for persistent angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13444–13449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110121108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saksela O, Moscatelli D, Sommer A, Rifkin DB. Endothelial cell-derived heparan sulfate binds basic fibroblast growth factor and protects it from proteolytic degradation. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:743–751. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.2.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faham S, Hileman RE, Fromm JR, Linhardt RJ, Rees DC. Heparin structure and interactions with basic fibroblast growth factor. Science. 1996;271:1116–1120. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moya ML, Garfinkel MR, Liu X, Lucas S, Opara EC, Greisler HP, Brey EM. Fibroblast growth factor-1 (FGF-1) loaded microbeads enhance local capillary neovascularization. J Surg Res. 2010;160:208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamalice L, Le Boeuf F, Huot J. Endothelial cell migration during angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;100:782–794. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259593.07661.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nam J, Huang Y, Agarwal S, Lannutti J. Improved cellular infiltration in electrospun fiber via engineered porosity. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2249–2257. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sigrist S, Mechine-Neuville A, Mandes K, Calenda V, Legeay G, Bellocq JP, Pinget M, Kessler L. Induction of angiogenesis in omentum with vascular endothelial growth factor: influence on the viability of encapsulated rat pancreatic islets during transplantation. J Vasc Res. 2003;40:359–367. doi: 10.1159/000072700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uriel S, Brey EM, Greisler HP. Sustained low levels of fibroblast growth factor-1 promote persistent microvascular network formation. Am J Surg. 2006;192:604–609. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tokuda H, Takai S, Hanai Y, Harada A, Matsushima-Nishiwaki R, Kato H, Ogura S, Kozawa O. Potentiation by platelet-derived growth factor-BB of FGF-2-stimulated VEGF release in osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Metab. 2008;26:335–341. doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0829-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Masaki I, Yonemitsu Y, Yamashita A, Sata S, Tanii M, Komori K, Nakagawa K, Hou X, Nagai Y, Hasegawa M, Sugimachi K, Sueishi K. Angiogenic gene therapy for experimental critical limb ischemia: acceleration of limb loss by overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor 165 but not of fibroblast growth factor-2. Circ Res. 2002;90:966–973. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000019540.41697.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whalen GF, Shing Y, Folkman J. The fate of intravenously administered bFGF and the effect of heparin. Growth factors. 1989;1:157–164. doi: 10.3109/08977198909029125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Edelman ER, Nugent MA, Karnovsky MJ. Perivascular and intravenous administration of basic fibroblast growth factor: vascular and solid organ deposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1513–1517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schlessinger J, Plotnikov AN, Ibrahimi OA, Eliseenkova AV, Yeh BK, Yayon A, Linhardt RJ, Mohammadi M. Crystal structure of a ternary FGF-FGFR-heparin complex reveals a dual role for heparin in FGFR binding and dimerization. Mol Cell. 2000;6:743–750. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gospodarowicz D, Cheng J. Heparin protects basic and acidic FGF from inactivation. J Cell Physiol. 1986;128:475–484. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041280317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sakakibara Y, Tambara K, Sakaguchi G, Lu F, Yamamoto M, Nishimura K, Tabata Y, Komeda M. Toward surgical angiogenesis using slow-released basic fibroblast growth factor. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;24:105–111. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00159-3. discussion 112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perets A, Baruch Y, Weisbuch F, Shoshany G, Neufeld G, Cohen S. Enhancing the vascularization of three-dimensional porous alginate scaffolds by incorporating controlled release basic fibroblast growth factor microspheres. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2003;65:489–497. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vashi AV, Abberton KM, Thomas GP, Morrison WA, O’Connor AJ, Cooper-White JJ, Thompson EW. Adipose tissue engineering based on the controlled release of fibroblast growth factor-2 in a collagen matrix. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:3035–3043. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

HUVEC proliferation by different concentration of FGF-2 treatment for 3 days. HUVEC proliferation was measured by Cyquant assay (n=5; using one-way ANOVA statistical analysis and Tukey multiple comparison test, *p<0.05 vs. 3 and 500 ng/ml of FGF-2 treated groups, ###p<0.001 vs. 0, 1, and 1000 ng/ml of FGF-2 treated groups).