Abstract

The consequences of heavy alcohol use remain a serious public health problem. Consistent evidence has demonstrated that both genetic and social influences contribute to alcohol use. Research on gene-environment interaction (GxE) has also demonstrated that these social and genetic influences do not act independently. Instead, certain environmental contexts may limit or exacerbate an underlying genetic predisposition. However, much of the work on GxE and alcohol use has focused on adolescence and less is known about the important environmental contexts in young adulthood. Using data from the young adult wave of the Finnish Twin Study, FinnTwin12 (N=3,402), we used biometric twin modeling to test whether education moderated genetic risk for alcohol use as assessed by drinking frequency and intoxication frequency. Education is important because it offers greater access to personal resources and helps determine one’s position in the broader stratification system. Results from the twin models show that education did not moderate genetic variance components and that genetic risk was constant across levels of education. Instead, education moderated environmental variance so that under conditions of low education, environmental influences explained more of the variation in alcohol use outcomes. The implications and limitations of these results are discussed.

Keywords: Young adults, Alcohol use, Education, Gene-environment interaction, Twin models

Introduction

The burden of alcohol use and the problems that arise from it are felt at the individual, community, and national levels. Globally, an estimated 5.9% of all deaths and 5.1% of the disease burden are linked to alcohol consumption (World Health Organization, 2014). The causes of alcohol use, both genetic and environmental, are far from static. Instead, there is a dynamic process unfolding across the life course in which social and genetic influences change over time. Environmental contexts are more important in early adolescence and genetic influences increase with age (Dick, 2011; Rose et al., 2001). In addition to changes in the relative importance of environmental and genetic factors across development, there is also evidence to suggest that these factors interact: the importance of genetic factors may be dependent on key environmental factors at any given point (Cooke et al., 2015; Dick et al., 2009; Heath et al., 1989; Kaprio et al., 1987; Penninkilampi-Kerola et al., 2005; Rose et al., 2001).

In this paper, we explore whether educational attainment in young adulthood moderates genetic risk for alcohol use. We focus on both regular alcohol use (in the form of drinking frequency) and more problematic, heavy use (in the form of intoxication frequency). Considering both outcomes allows us to explore different dimensions of alcohol use. These include frequent use, which may reflect a culturally accepted activity and pose relatively little health risk (Poli et al., 2013) and frequent intoxication, which represents an important health-risk behavior and significantly contributes to mortality and the overall disease burden (Rehm et al., 2009), especially as use increases (Sipilä et al., 2016). Our research design incorporates genetic and environmental influences patterned by broader social forces (Boardman et al., 2013) in a life course framework focusing on the interplay of genes and environment at a given stage of human development.

One of the most consistent findings in social epidemiology is the link between health and wealth, whereby those at the higher end of the socioeconomic continuum experience better health than those at the lower end. This relationship is so well documented that socioeconomic status (SES) has been theorized as a "fundamental cause" of disease (Link & Phelan, 1995). Education is a key mechanism linking SES and health because of its influence on an individual’s position in the broader stratification system and the resources that accompany that position. Accordingly, understanding how education may interact with latent genetic risk is an important area of study, especially during young adulthood. In general, this is the period when alcohol use reaches its peak level (Chen & Jacobson, 2012). It also represents an important transitional period where social controls that previously constrained behavior, such as parents or legal availability of alcohol, are now dramatically decreased and new social controls that may limit risky behaviors such as heavy drinking come online. This makes young adulthood a critical period in which individuals are susceptible to becoming heavy users.

Education and Health

The Education and Health Relationship

Typically, three theoretical models are used to explain the association between education and health. The social causation model theorizes that education causally influences health. Mechanisms through which this occurs include better working conditions, greater sense of control, increased social capital, better labor market prospects, and improved health behaviors; such as diet, exercise, and not smoking (Cutler et al., 2015; Li & Powdthavee, 2015; Margolis, 2013; Ross & Wu, 1995; Song, 2011). Education becomes even more important across the life course, as the health consequences of educational disparities diverge across time (Cohen et al., 2013; Mirowsky & Ross, 2008). For alcohol-related behaviors, lower educational achievement is associated with greater likelihood of alcohol dependence (Crum et al., 1993; Gilman et al., 2008) and problems from substance use (Fothergill & Ensminger, 2006). In contrast, the social selection model suggests that poor health and health-related behaviors result in lower educational attainment. Research into the impact of early-life health has found both childhood and adolescent health to be a strong predictor of adult education (Haas, 2006; Lynch & von Hippel, 2016). In regards to substance use, alcohol use and dependence are associated with greater termination of education at the high school and college levels, and a reduced likelihood of entering college (Breslau et al., 2008). Heavy alcohol use specifically is associated with poorer school performance (Latvala et al., 2014).

Finally, the common-cause model argues some underlying cause contributes to both educational attainment and health. These include both environmental and genetic factors. Parental SES is significantly linked to both health and educational attainment later in life (Haas, 2006, 2008; Lynch & von Hippel, 2016). General intelligence is also predictive both of educational achievement (Deary et al., 2007) and later health (Der et al., 2009). At least part of the relationship between education and self-rated health is due to common-genetic factors (Amin et al., 2015; Boardman et al., 2015; Fujiwara & Kawachi, 2009; Lundborg, 2013) and correlations between education and various health outcomes and behaviors, including alcohol consumption, are no longer significant after accounting for common genetic and familial environments (Amin et al., 2015; Fujiwara & Kawachi, 2009; Lundborg, 2013), suggesting a common genetic or environmental influence. Recent genome-wide efforts have also identified 74 genetic variants associated with educational attainment that show significant overlap with mental health outcomes (Okbay et al., 2016).

These competing hypotheses describe a complex relationship. Both selection and causation are important and dependent on the life course period under investigation. This may be important for alcohol use specifically, as frequency of both use and heavy use tends to change dramatically across adolescence into adulthood (Chen & Jacobson, 2012). Moving beyond the focus on causal direction and into a model that incorporates the interplay between genetic and social risk factors may provide a detailed understanding during this specific stage in the life course.

Insight from Gene-Environment Interaction

Gene-environment interaction (GxE) focuses on how the importance of genetic factors changes according to specific environmental characteristics. In GxE research, education is often used as a component of SES. Competing explanations exist for how education, or SES more broadly, may contribute to genetic risk for alcohol use. The diathesis-stress model posits that at lower SES, individuals are exposed to greater amounts of stress and the genetic predisposition for alcohol use will be exacerbated (South et al., 2015), similar to the ideas within the stress process tradition in medical sociology (Pearlin et al., 1981). Another possible explanation is related to social control and/or opportunity (Shanahan & Hofer, 2005). Under this scenario, individuals with greater education or SES would have greater opportunity to express their genetic predisposition because of increased access to contexts where alcohol use is normative, such as a college (Timberlake et al., 2007) or urban settings (Dick et al., 2001; Rose et al., 2001).

The influence of education on genetic risk may vary across different outcomes. For internalizing disorders, SES moderated genetic and environmental variance so that environmental characteristics explained more variation at the lower end of the SES continuum and genetic factors became more prominent at the higher end of the SES spectrum (South & Krueger, 2011). SES also moderated genetic risk in major depression: lower education was found to greatly exacerbate genetic risk for major depression (Mezuk et al., 2013). In regards to self-rated physical health, genetic influence was greater at lower levels of education, suggesting that education may offer some protective effect against any genetic predisposition for poor health (Johnson et al., 2010b).

GxE research focusing on education and substance use has provided support for both the diathesis-stress and social opportunity explanations depending on the specific phenotype (or trait), though limited research using twin-designs exists. Education has been shown to moderate genetic variance in drinks per week (Johnson et al., 2010a), drinking amount (Hamdi et al., 2015), smoking initiation (McCaffery et al., 2008), and smoking quantity (Johnson et al., 2010a) such that genetic influences were greater under conditions of low education, providing support for the diathesis-stress model. In a young adult sample, education moderated environmental, but not genetic, variance in both alcohol-related problems and the maximum number of drinks consumed in 24 hours such that environmental factors were stronger at lower levels of educational attainment (Latvala et al., 2011). Similarly college attendance moderated genetic risk in alcohol use such that genetic factors were more prominent for those enrolled in a 4 year institution (Timberlake et al., 2007), suggesting that the college environment provided greater opportunity to express an underlying genetic predisposition. It is possible that both explanations of educational influences on genetic predisposition for alcohol use are correct, but that the results depend on the age of the sample. These inconsistencies reiterate the importance of examining specific developmental stages when studying alcohol use. Because of the dynamic process surrounding genes and environments related to alcohol use, researchers must be cognizant of the context in which they are examining GxE.

Current Study

This review of the literature guided our analyses in several ways. First, because of the concerns with direction of causation and genetic influences on alcohol use, using a genetically informed design allowed us to model GxE while simultaneously accounting for the possibility of gene-environment correlation (rGE), or the tendency for certain environments to be made up of individuals with certain genetic profile (Purcell, 2002). In the case of alcohol use, this could include the tendency for individuals at genetic risk for heavy drinking to also complete fewer years of education. Second, research focusing on young adulthood found education moderated environmental rather than genetic variance (Latvala et al., 2011), while contextual factors linked to education during this stage of the life course, such as college attendance, increased genetic influences in alcohol use (Timberlake et al., 2007). Therefore, we hypothesized that education would moderate both environmental and genetic influences on alcohol use phenotypes. Under conditions of low education, we expected environmental influences to be more important and under conditions of high education we expected genetic influences to be more important.

We examine our hypotheses using a sample of Finnish, young adult twins. Finland provides a unique context in which to study alcohol use because of both the prevalence and cultural acceptance of alcohol use. The majority of Finns (Females = 75.8%, Males = 63.7%) aged 15–24 reported using alcohol in the previous year, and many (Females = 29.3%, Males = 32.9%) also reported having drunk six or more portions in one sitting at least once a month (Helldán & Helakorpi, 2015). In Finland, 36.5% of Finns (53.7% of those who drink) have engaged in heavy episodic drinking in the past 30 days compared to only 16.9% (24.5% of drinkers) of those in the United States (WHO, 2014). Though the purchase of alcohol becomes legal at age 18 in Finland (for beer and wine, age 20 for spirits), heavy use appears to start early, as 33% of 15–16 year olds reported having been drunk before the age of 13 (Jernigan, 2001), though this may have declined in recent years (Kuntsche et al., 2011).

Methods

Sample

Our sample came from the younger cohort of the Finnish Twin Cohort Study (FinnTwin12). Data were collected from Finland’s Population Registry, permitting comprehensive nationwide ascertainment. Collection began in September 1994 for twins born from 1983 to 1987, across 5 birth cohorts. The FinnTwin12 Study was established to examine genetic and environmental influences on health-related behaviors (Kaprio, 2013), particularly the development of alcohol use and abuse (see Dick et al., 2009 for a full description). Baseline collection occurred when twins were approximately 12 years old, with a sample of approximately 5600 twins and their families (87% participation rate). Follow-up surveys occurred at ages 14, 17.5 and as young adults between age 20 and 26. Data for this study come from the young adult follow up, including 3402 participants (61%) of the original sample. Twin zygosity was determined at baseline using a well validated scale (Sarna et al., 1978). Zygosity classification based on survey items showed 97% correspondence with classification based on DNA polymorphisms in 395 same-sex twin pairs (Jelenkovic et al., 2011). Participants and their parents were fully informed of study procedures and gave consent to participate. The Ethical Committee of the Helsinki University Central Hospital District approved all stages of data collection.

Measures

Drinking Frequency and Intoxication Frequency

Drinking frequency was determined by asking respondents "How often do you use alcohol? Include also those occasions when you use only a small amount of alcohol, for example half bottle of beer or drop of wine." Intoxication frequency was determined by asking "How often you use alcohol in such a way that you get really drunk?" Responses included "never" (0), "once a year" (1), 2–4 times a year (2), "every other month" (3), "once a month" (4), "more than once a month" (5), "once a week" (6), "more than once a week" (7), and "daily" (8). Responses were recoded to create pseudo-continuous items that reflected how often respondents engaged in these behaviors in a given (30 day) month (Cooke et al., 2015; Dick et al., 2001). This item more accurately reflected the differences between response categories, especially at the upper extremes. Measures of drinking frequency and intoxication were both log-transformed (+1 to retain zeros) to adjust for positive skew.

Educational Attainment

Educational attainment was constructed using the same method as Latvala and colleagues (2011). Participants reported their level of education and their ongoing study as categorical variables. These measures were used to calculate a years of education variable based on the time taken to complete each level of study, and their current status. Primary education in elementary school is completed over a 9-year period, graduating 10th grade adds an additional voluntary year (9+1). Secondary education is divided into academic and non-academic streams and includes an additional 2 to 3 years. Vocational high schools in Finland prepare people for a profession and involve 13 to 16 years total education. The highest level of education is attained at the masters or doctoral level. If participants reported they were currently studying, the standard duration of that type of degree was divided by two and added to their years of education.

Analytic Plan

We used biometric twin modeling, a common approach in genetic epidemiology that utilizes twin data and allows variance in a phenotype to be decomposed into portions explained by additive genetic factors (A), shared environmental influences between twins (C), and environmental factors unique to each twin (E) based on assumptions regarding shared genetic and environmental contributions between monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twins. MZ twins share all of their genetic variation while DZ twins share on average half. The shared environmental component models environmental influences that make siblings more similar to one another and the correlation between twins is fixed to 1. Comparing within-twin pair correlations can approximate initial estimates for genetic and environmental influences. If shared environmental effects (C) are important, the DZ correlation will exceed half the MZ correlation.

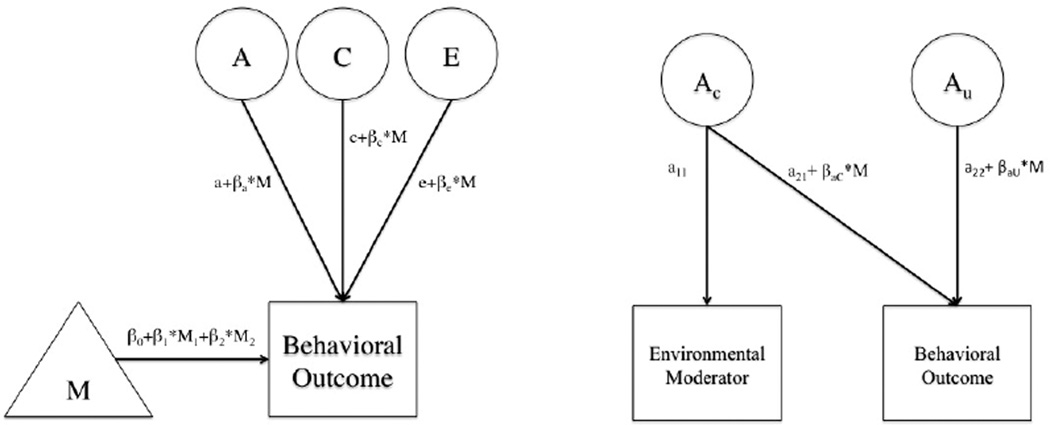

The univariate biometric model has been useful in estimating heritability, or the proportion of variance in a phenotype that can be explained by genetic differences. Extension of the univariate model has allowed the modeling of GxE, which estimates how variance in traits change across levels of a measured environmental moderator by including its effect on the paths for each component (Purcell, 2002). GxE can also be examined using a bivariate model, which includes the unique and shared ACE components for the trait and the environmental moderator as well as the moderation on these components. Both the univariate and bivariate model allow for detection of GxE in the presence of rGE, though in the case of the univariate model this is limited to genetic factors that are unique to the trait. Depictions of both models can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Extended Univariate and Bivariate GxE Models.

Figures show extended univariate model (left) and simplified bivariate model (right) with only the genetic components included for ease of display. Moderation is estimated through the β on each of the a, c, and e paths. In the bivariate case, the moderation can act on both the shared path between the moderator and trait (a21) and the path unique to the trait (a22). In the case when the extended univariate model is selected over the bivariate, all of the shared paths between trait and moderator are collapsed into the means portion of the model (M).

There is greater power to detect moderation effects in the univariate model, but it can lead to problems of false positives when there is moderation on the shared paths between moderator and phenotype (van der Sluis et al., 2012). In the case of shared genetic variance between the moderator and phenotype, the bivariate model is more appropriate. For all models, we first fit the bivariate model and tested for significant moderation on both the unique and common paths of the phenotype. If there was no significant moderation on the cross-paths, we moved to the extended univariate model (van der Sluis et al., 2012). The extended univariate model included the effect of each twin’s education as well as their co-twin’s education on the mean for each alcohol phenotype, which resolved issues of inflated false positives in the GxE model (for a more detailed description see van der Sluis et al., 2012). In order to conserve space, we only present the results from the bivariate GxE models when we could not move on to the simpler extended univariate GxE model.

Models initially allowed all parameters to be estimated freely across sex (Neale et al., 2006). In the case where sex differences were not significant, the model was simplified. We performed a global test of moderation by constraining the moderation effects on all of the components to be zero. This provided an omnibus test before testing for moderation on individual paths. All analyses used the OpenMx package in R (Boker et al., 2011). Age was included as a covariate on the mean of the phenotype. Univariate models without GxE are provided for descriptive purposes.

Results

Univariate Twin Models and Twin Correlations

The twin and bivariate correlations are presented in Table 2. Bivariate correlations revealed that there were significant though weak differences across educational attainment in both drinking frequency (r = .04, p<.05) and intoxication frequency (r = −.11, p<.001). Table 3 summarizes the descriptive results for sex-limited univariate models. The ACE estimates in Table 3 suggest that alcohol use had higher heritability in males (A= 66.7% for drinking frequency and 56.8% for intoxication frequency) compared to females (A= 34.3% for drinking frequency and 40.1% for intoxication frequency), while education had higher heritability in females (A= 69.6%) compared to males (A= 45.2%); however, because of the overlap in confidence intervals, many of these sex differences were not significant.

Table 2.

Twin and Bivariate Correlations

| Variables | Twin Correlations | Bivariate Correlations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MZF | DZF | MZM | DZM | DZO | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 1 Intoxication frequency | 0.50 | 0.28 | 0.63 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 1.00 | - | - |

| 2 Drinking frequency | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.71 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.64*** | 1.00 | - |

| 3 Years of education | 0.72 | 0.49 | 0.76 | 0.51 | 0.41 | −0.11*** | .04* | 1.00 |

| N (twin pairs) | 344 | 297 | 265 | 271 | 618 | |||

MZF= monozygotic females; DZF= dizygotic females; MZM= monozygotic males; DZM= dizygotic males; DZO= dizygotic opposite sex

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Table 3.

Sex-limited Univariate ACE Estimates.

| Variables | Sex | a | c | e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intoxication frequency | Female | .401 (.155, .547) |

.094 (.000, .301) |

.504 (.432, .589) |

| Male | .568 (.341, .660) |

.030 (.000, .225) |

.403 (.333, .487) |

|

| Drinking frequency | Female | .343 (.095, .559) |

.153 (.000, .363) |

.504 (.430, .589) |

| Male | .667 (.521, .733) |

.009 (.000, .139) |

.323 (.265, .395) |

|

| Years of education | Female | .696 (.452, .765) |

.038 (.000, .267) |

.266 (.224, .317) |

| Male | .452 (.243, .780) |

.314 (.003, .500) |

.234 (.188, .296) |

Estimates represent proportion of total variance explained by additive genetic (a), shared environmental (c), and unique environmental (e) influences. Likelihood-based confidence intervals presented in parentheses.

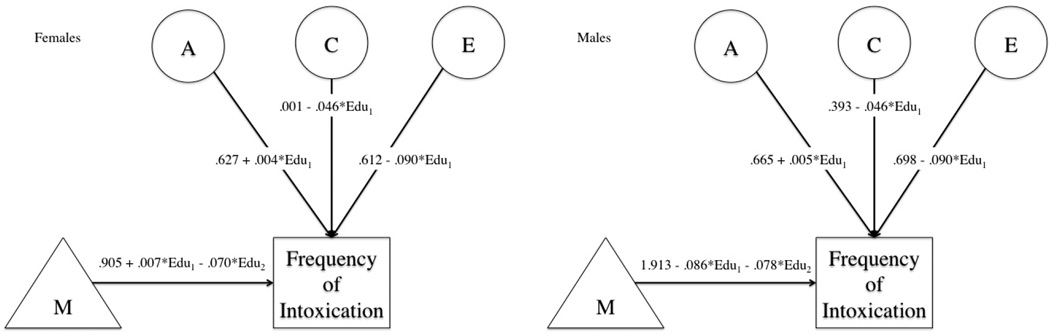

GxE Models for Intoxication frequency

Model fitting results and path estimates for intoxication frequency are provided in Table 4 and Figure 2, respectively. Estimates of the genetic correlation between education and intoxication frequency (females rG = .01; males rG = −.12) were not significant. We found no evidence of moderation on the cross paths in the bivariate GxE model. Therefore, we used the extended univariate model. Constraining the effects of moderation (p=.129) to be equal across sex did not result in a significant drop in model fit, though constraining the variances themselves resulted in poorer fit (p<.001). Next, we dropped all of the moderation effects simultaneously. This resulted in a significant drop in fit (Δ - 2LL=25.63, p<.001), meeting our initial requirement for a global test. Dropping the moderation on either the additive genetic path (p=.873) or the shared environmental path (p=.421) did not result in significantly worse fit. Finally, removing the moderation on the unique environmental resulted in significantly poorer model fit (p<.001). The final test dropped the effect of education on the means and resulted in a significantly worse fit (Δ - 2LL=16.12, p=.003). Path estimates are provided in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Extended Univariate GxE Models for Education and Intoxication Frequency

| Model | Ref. Model |

EP | −2LL | df | AIC | Δ-2LL | Δdf | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Full sex-limited moderation |

NA | 20 | 6573.34 | 2476 | 1621.34 | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 Moderation effects constrained across sex |

1 | 17 | 6579.00 | 2479 | 1621.00 | 5.66 | 3 | 0.129 |

| 3 Variance and moderation constrained across sex |

2 | 14 | 6612.57 | 2482 | 1648.57 | 33.56 | 3 | 0.000 |

| 4 No Moderation | 2 | 14 | 6604.63 | 2482 | 1640.63 | 25.63 | 3 | 0.000 |

| 5 No Moderation on A | 2 | 16 | 6579.03 | 2480 | 1619.03 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.873 |

| 6 No Moderation on C | 2 | 16 | 6579.65 | 2480 | 1619.65 | 0.65 | 1 | 0.421 |

| 7 No Moderation on E | 2 | 16 | 6593.92 | 2480 | 1633.92 | 14.92 | 1 | 0.000 |

| 8 No Moderation on Means | 2 | 13 | 6600.27 | 2483 | 1634.27 | 21.26 | 4 | 0.000 |

Analyses based on 1254 twin pairs ( MZF = 284, MZM = 179, DZF = 244, DZM = 167, DZO = 380).

Ref model = comparison model number for Δ-2LL test; EP =number of estimated parameters.

Figure 2. Path Estimates for Intoxication Frequency GxE Models.

Figures show path and moderation estimates from full model for intoxication frequency in both females (left) and males (right). Each means portion of the model includes the twin’s education (Edu1) and the influence of their co-twin’s education (Edu2).

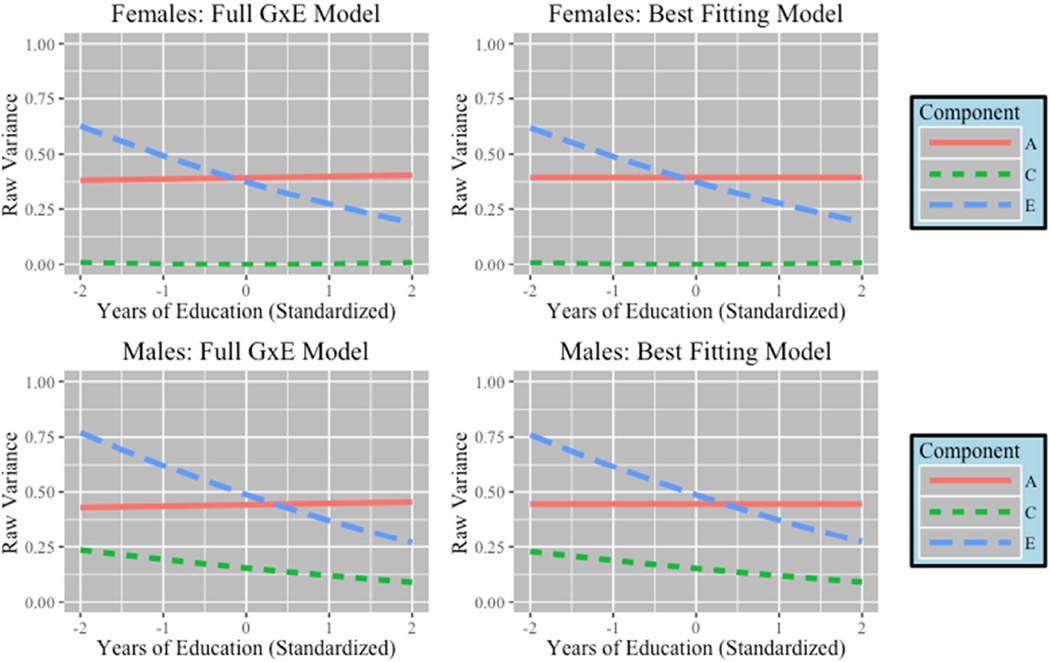

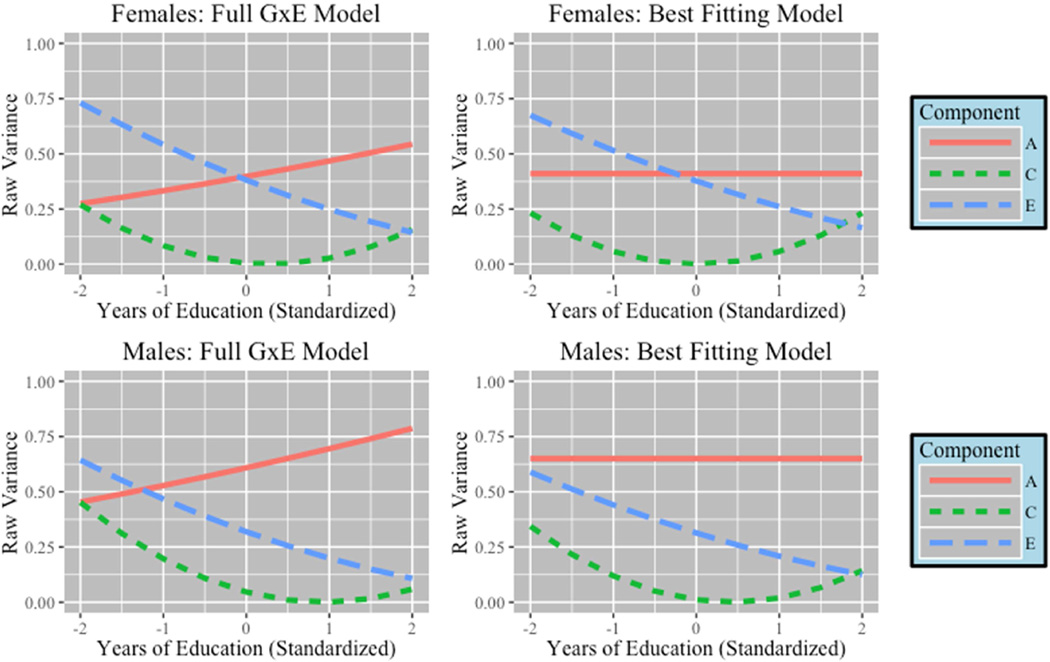

Figure 3 provides a graphical representation of the change in variance across levels of education (presented in standardized units) from the full model and best fitting models. While the additive genetic component did not change as a function of education, heritability in intoxication frequency was greater at higher levels of education due to the shrinking influence of the unique environment. At high levels of education genetic influences accounted for a larger portion of the standardized variance (Females = 66%, Males = 55%) compared to genetic influences at low levels of education (Females = 39%, Males = 31%) where environmental factors explained a greater proportion of the variance than genetic factors

Figure 3. Change in Variance Components for Intoxication Frequency.

Results from GxE models for intoxication frequency. Lines represent changes in raw variance of components across educational attainment (standardized). Only the change in unique environment (E) was significant.

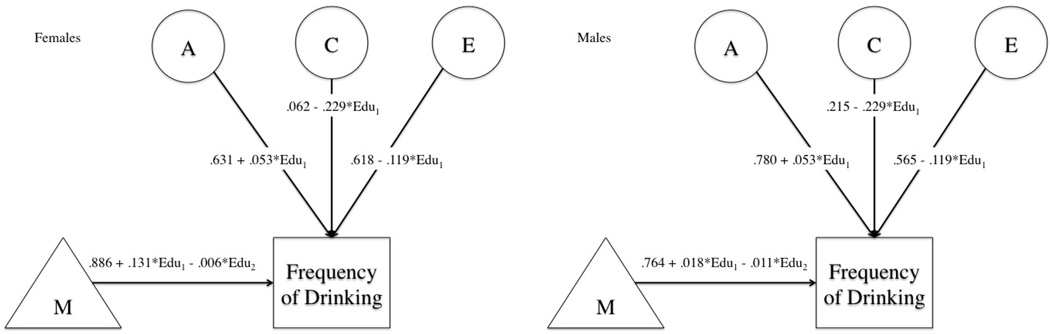

GxE Models for Drinking frequency

Table 5 presents the GxE results for the drinking frequency GxE models. Overall the results were similar to those found in the intoxication frequency models, with some slight differences. The bivariate model revealed that genetic correlations between education and drinking frequency (females rG = .07; males rG =.10) were not significant. Because education did not moderate any of the shared paths we fit the more parsimonious extended univariate model. We constrained the effects of education to be equal across sex (p=.938), but could not constrain the variances to be equal (p=.002). This provided a base model to test the moderation effects of education.

Table 5.

Extended Univariate GxE Models for Education and Drinking Frequency

| Model | Ref. Model |

EP | −2LL | df | AIC | Δ-2LL | Δdf | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Full sex-limited moderation |

NA | 20 | 6565.06 | 2476 | 1613.06 | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 Moderation effects constrained across sex |

1 | 17 | 6565.47 | 2479 | 1607.47 | 0.41 | 3 | 0.938 |

| 3 Variance and moderation constrained across sex |

2 | 14 | 6580.32 | 2482 | 1616.33 | 14.85 | 3 | 0.002 |

| 4 No Moderation | 2 | 14 | 6610.79 | 2482 | 1646.79 | 45.32 | 3 | 0.000 |

| 5 No Moderation on A | 2 | 16 | 6567.09 | 2480 | 1607.09 | 1.63 | 1 | 0.203 |

| 6 No Moderation on C | 2 | 16 | 6583.88 | 2480 | 1623.88 | 18.41 | 1 | 0.000 |

| 7 No Moderation on E | 2 | 16 | 6591.05 | 2480 | 1631.05 | 25.58 | 1 | 0.000 |

| 8 No Moderation on Means |

2 | 13 | 6587.23 | 2483 | 1621.23 | 21.76 | 4 | 0.000 |

Analyses based on 1254 twin pairs ( MZF = 284, MZM = 179, DZF = 244, DZM = 167, DZO = 380).

Ref model = comparison model number for Δ-2LL test; EP =number of estimated parameters.

The global test of moderation was highly significant (Δ - 2LL=45.32, p<.001). As with intoxication frequency, education did not significantly moderate the additive genetic component on drinking frequency (p=.203). Dropping the effect of education on either the shared environment (Δ - 2LL=18.41, p<.001) or unique environment (Δ - 2LL=25.48, p<.001) paths resulted in a substantial drop in the log-likelihood. The last model dropped the impact of education on the mean of drinking frequency and resulted in a significant decrease in fit of the model (p<.001). Figure 4 provides the path estimates from the full model.

Figure 4. Path Estimates for Drinking Frequency GxE Models.

Figures show path and moderation estimates from full model for drinking frequency in both females (left) and males (right). Each means portion of the model includes the twin’s education (Edu1) and the influence of their co-twin’s education (Edu2).

Figure 5 presents the breakdown in the unstandardized variance components by level of education (standardized) for the full and best fitting models. Though the change in additive genetic variance appears dramatic across the full model, it was not significant. As was the case with intoxication frequency, at lower levels of education, environmental components had a stronger influence. The influence of environment declined as education increased and shared environments only mattered at either extreme. Genetic variance in male respondents explained the greatest proportion of the variance regardless of educational attainment. This was not the case for females. Overall, heritability changed because of the shift in both the shared and unique environmental variances across levels of education. Genetic influences contributed relatively less to the standardized variance at lower levels of education (Females = 31%, Males = 41%) compared to higher levels of education (Females = 51%, Males = 71%).

Figure 5. Change in Variance Components for Drinking Frequency.

Results from GxE model for drinking frequency. Lines represent changes in raw variance of components across educational attainment (standardized). Change in both shared (C) and unique environment (E) was significant.

Discussion

Our goal in the current analysis was to further explore the role of education in genetic predisposition for alcohol use in young adulthood, focusing on both drinking frequency and intoxication frequency. We expected education to moderate genetic and environmental variance such that genetic factors would account for more variance under conditions of greater education and environmental factors would account for more variance under conditions of lower education. However, education did not moderate the latent genetic predisposition for either drinking or intoxication frequency. Rather, education moderated environmental sources of variance in these traits so that greater variation in both alcohol phenotypes was attributable to environmental influences under conditions of lower educational attainment. These results are in line with previous research on education and alcohol use in young adulthood on alcohol-related problems on a different Finnish sample (Latvala et al., 2011), and extend them to consider indicators of consumption. This is important because though alcohol consumption and problems share genetic variance, they each have distinct genetic influences (Dick et al., 2011; Kendler et al., 2010). Education had a similar influence for both male and female twins, but the variance could not be constrained to be equal across sex, and genetic factors were stronger in males.

In young adulthood, educational attainment did not moderate genetic predispositions for intoxication frequency drinking. Instead, it moderated the environmental sources of variance in these outcomes. At the lower end of the educational continuum, environmental conditions explained a larger proportion of the variance. At the higher end, genetic influences were of greater importance. This was not due to any influence of education on genetic variance directly. Rather, it was because of the declining influence of unique environmental factors. The greater importance of environmental factors at lower levels of education are similar to findings for both internalizing disorders (South & Krueger, 2011) and intelligence (Hanscombe et al., 2012; Turkheimer et al., 2003). Interestingly, we found no evidence of gene-environment correlation for either phenotype, suggesting that overlapping genetic causes do not significantly account for the weak relationship between education and frequency of alcohol use or intoxication during young adulthood.

What conditions associated with low educational attainment may influence these phenotypes? One methodological explanation is the more accurate reporting of drinking behaviors in those with higher education. Because the unique environmental component also includes measurement error, this is a possibility. However, given the similarity in our findings to previous GxE research (Latvala et al., 2011) and literature on environmental influences on alcohol use associated with low education, we do not believe this fully accounts for this finding. Another possibility reflects the social conditions associated with low education. Low SES, and with it low education, is related to various negative conditions including increased exposure to stressors (Turner & Avison, 2003) reduced personal and financial resources (Ross & Mirowsky, 1999; Ross & Wu, 1995), or moving to disadvantaged neighborhoods (Sharkey, 2012) characterized by greater levels of disorder (Sampson et al., 1997). Educational differences could also reflect differences in residence, as those with less education tend to live in rural areas where environmental factors have a stronger influence on alcohol use (Dick et al., 2001; Rose et al., 2001). Regardless of the specific environmental influences, the bivariate correlations between education and both intoxication frequency (r = −.11) and drinking frequency (r = .04) were weak. Averages in both phenotypes were roughly equivalent across education during young adulthood.

One final possibility reflects the life course timing of these data. Because those with higher education could still be in school, it is possible that they are in college settings where regular alcohol use is normative, whereas those with lower education are more likely be involved in the workforce or have started families. As these individuals transition into adult roles, they will move into environments that constrain the influence of genetic predispositions, such as marriage (Heath et al., 1989), especially as marriage is more prevalent among the better educated (Lundberg et al., 2016). Future work should explore the possibility of these conditions.

The present findings should be interpreted in terms of the social context of Finland. The social conditions in Finland are very different from those in the United States. Estimates of income inequality between these countries (GINI coefficient: where 0 = perfect equality and 100 = perfect inequality) indicate that inequality in the US (GINI= 41.1) is much greater than in Finland (GINI= 27.1) (World Bank Group, 2016). Finland also has a more equitable educational system and socioeconomic disadvantage has a weaker influence on educational outcomes (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2013). Greater levels of social equality likely influence environmental conditions, that may affect the genetic and environmental etiology of alcohol use, especially conditions associated with SES. Though these questions are beyond the current analyses, evidence from a recent meta-analysis of the heritability of intelligence across levels of SES suggests that social context in the US is unique. Only in the USA did SES significantly moderate variance in IQ such that environmental factors had stronger influences at lower levels of SES and genetic factors became stronger as SES increased (Tucker-Drob & Bates, 2016). National differences in social conditions related to inequality may similarly impact the heritability of alcohol-related traits. Because variability in social conditions is reduced in Finland, our estimates of gene-environment interaction are likely to be conservative, and may be more pronounced in countries with greater social inequality, like the USA.

Several additional considerations should be made when interpreting these results. First, although education is shaped by non-genetic factors, it is not exogenous such as environmental moderators like state-level tobacco policies (Boardman, 2009) or regional alcohol sales (Dick et al., 2001). Environmental moderators often have some heritable component (Kendler & Baker, 2007). The estimated the heritability of educational attainment is about 40% (Branigan et al., 2013). Non-twin samples estimate the heritability of education to be roughly 33% (Boardman et al., 2015). Genome-wide studies have identified 74 loci associated with educational attainment (Okbay et al., 2016). However, educational attainment had much stronger shared environmental contributions than other outcomes, at approximately 36% (Branigan et al., 2013). Thus, education appears to reflect both genetic and non-genetic factors.

Second, our measure of educational attainment was extrapolated from two measures in the data, similar to other analyses on the Finnish population (Latvala et al., 2011). We reran the all models with an ordinal measure of education based on the level of schooling completed. Overall, these models produced nearly identical results, with one exception. In the models for drinking frequency using the ordinal measure of education, the moderation effect on the shared environmental component was not significant (p=.053) though it was just above the traditional significance threshold. These checks suggest our results were robust to the specific measure of educational attainment.

Finally, because genetic and environmental influences on substance use change across development (Dick, 2011; Rose et al., 2001), work covering multiple periods is needed. Although young adulthood is a critical period that may shape individual trajectories for years to come, future research should determine what influence, if any, educational attainment has on the change in genetic and environmental contributions over time. This is especially important as individuals move into middle and later life where disparities in health and the consequences of poor health-behaviors become more apparent.

In conclusion, environmental conditions associated with low education have implications for drinking and intoxication in young adulthood. Incorporating a quantitative genetic design, we demonstrated that education did not influence genetic risk for these behaviors, but rather it shaped the environmental influences on alcohol use in young adulthood. The main effects of education revealed only weak differences in drinking or intoxication frequency at this point in the life course. Future research focusing on GxE should look into social contexts associated with low education, including work conditions, neighborhood factors, and stress to examine whether these moderate genetic risk for alcohol use in young adulthood. Use of measured genes will also help to demonstrate whether these results are replicable in non-twin samples.

Table 1.

FinnTwin12 Descriptive Statistics (N=3,402)

| Females (N=1878) | Males (N=1435) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean( SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range |

| Age | 24.23 (1.64) | 19.29 – 27. 00 | 24.15 (1.65) | 20.87 – 27.50 |

| Years of education | 13.22 (2.03) | 9.0 – 18.5 | 12.62 (1.92) | 9.0 – 18.5 |

| Intoxication frequency | 0.94 (1.28) | 0 – 30 | 1.71 (1.91) | 0 – 30 |

| Drinking frequency | 3.15 (3.31) | 0 – 30 | 5.08 (5.43) | 0 – 30 |

Research Highlights.

Education moderated environmental variance in drinking or intoxication frequency.

Education did not moderate genetic variance in either outcome.

Environmental variance in alcohol use was stronger at lower levels of education.

Correlations between education and drinking or intoxication frequency were weak.

These correlations were not due to common genetic influences.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01AA015416, K02AA018755, and F32AA022269; the Academy of Finland (grants 100499, 205585, 118555, 141054, 265240, 263278, and 264146); and the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBİTAK) under award number 114C117. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Academy of Finland, or the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amin V, Behrman JR, Kohler H-P. Schooling has smaller or insignificant effects on adult health in the US than suggested by cross-sectional associations: new estimates using relatively large samples of identical twins. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;127:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman JD. State-level moderation of genetic tendencies to smoke. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:480. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.134932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman JD, Daw J, Freese J. Defining the Environment in Gene--Environment Research: Lessons From Social Epidemiology. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:S64–S72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman JD, Domingue BW, Daw J. What can genes tell us about the relationship between education and health? Social Science & Medicine. 2015;127:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boker S, Neale M, Maes H, Wilde M, Spiegel M, Brick T, et al. OpenMx: An Open Source Extended Structural Equation Modeling Framework. Psychometrika. 2011;76:306–317. doi: 10.1007/s11336-010-9200-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branigan AR, McCallum KJ, Freese J. Variation in the heritability of educational attainment: An international meta-analysis. Social forces. 2013;92:109–140. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Lane M, Sampson N, Kessler RC. Mental disorders and subsequent educational attainment in a US national sample. Journal of psychiatric research. 2008;42:708–716. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: Gender and racial/ethnic differences. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AK, Rehkopf DH, Deardorff J, Abrams B. Education and obesity at age 40 among American adults. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;78:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke ME, Meyers JL, Latvala A, Korhonen T, Rose RJ, Kaprio J, et al. Gene-Environment Interaction Effects of Peer Deviance, Parental Knowledge and Stressful Life Events on Adolescent Alcohol Use. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2015;18:507–517. doi: 10.1017/thg.2015.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Helzer JE, Anthony JC. Level of education and alcohol abuse and dependence in adulthood: a further inquiry. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:830–837. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.6.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM, Huang W, Lleras-Muney A. When does education matter? The protective effect of education for cohorts graduating in bad times. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;127:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ, Strand S, Smith P, Fernandes C. Intelligence and educational achievement. Intelligence. 2007;35:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Der G, Batty GD, Deary IJ. The association between IQ in adolescence and a range of health outcomes at 40 in the 1979 US National Longitudinal Study of Youth. Intelligence. 2009;37:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM. Developmental changes in genetic influences on alcohol use and dependence. Child Development Perspectives. 2011;5:223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Bernard M, Aliev F, Viken R, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J, et al. The role of socioregional factors in moderating genetic influences on early adolescent behavior problems and alcohol use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:1739–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Meyers JL, Rose RJ, Kaprio J, Kendler KS. Measures of Current Alcohol Consumption and Problems: Two Independent Twin Studies Suggest a Complex Genetic Architecture. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:2152–2161. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M. Exploring gene-environment interactions: Socioregional moderation of alcohol use. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2001;110:625. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fothergill KE, Ensminger ME. Childhood and adolescent antecedents of drug and alcohol problems: A longitudinal study. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2006;82:61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T, Kawachi I. Is education causally related to better health? A twin fixed-effect study in the USA. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;38:1310–1322. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman S, Breslau J, Conron K, Koenen K, Subramanian S, Zaslavsky A. Education and race-ethnicity differences in the lifetime risk of alcohol dependence. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2008;62:224–230. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.059022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas SA. Health selection and the process of social stratification: The effect of childhood health on socioeconomic attainment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47:339–354. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas SA. Trajectories of functional health: the long arm’of childhood health and socioeconomic factors. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66:849–861. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi NR, Krueger RF, South SC. Socioeconomic status moderates genetic and environmental effects on the amount of alcohol use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2015;39:603–610. doi: 10.1111/acer.12673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanscombe KB, Trzaskowski M, Haworth CM, Davis OS, Dale PS, Plomin R. Socioeconomic status (SES) and children’s intelligence (IQ): In a UK-representative sample SES moderates the environmental, not genetic, effect on IQ. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Jardine R, Martin NG. Interactive effects of genotype and social environment on alcohol consumption in female twins. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:38–48. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helldán A, Helakorpi S. Health behaviour and health among the Finnish adult population, spring 2014. Helsinki, Finland: National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jelenkovic A, OrtegaDAlonso A, Rose RJ, Kaprio J, Rebato E, Silventoinen K. Genetic and environmental influences on growth from late childhood to adulthood: a longitudinal study of two Finnish twin cohorts. American Journal of Human Biology. 2011;23:764–773. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan DH. Global Status Report: Alcohol and Young People. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W, Kyvik KO, Mortensen EL, Skytthe A, Batty GD, Deary IJ. Does Education Confer a Culture of Healthy Behavior? Smoking and Drinking Patterns in Danish Twins. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2010a;173:55–63. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W, Kyvik KO, Mortensen EL, Skytthe A, Batty GD, Deary IJ. Education reduces the effects of genetic susceptibilities to poor physical health. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2010b;39:406–414. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaprio J. The Finnish twin cohort study: an update. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2013;16:157–162. doi: 10.1017/thg.2012.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Langinvainio H, Romanov K, Sarna S, Rose RJ. Genetic influences on use and abuse of alcohol: a study of 5638 adult Finnish twin brothers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1987;11:349–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1987.tb01324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Baker JH. Genetic influences on measures of the environment: a systematic review. Psychological medicine. 2007;37:615–626. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Myers J, Dick D, Prescott CA. The Relationship Between Genetic Influences on Alcohol Dependence and on Patterns of Alcohol Consumption. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1058–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Kuntsche S, Knibbe R, et al. Cultural and gender convergence in adolescent drunkenness: Evidence from 23 european and north american countries. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165:152–158. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latvala A, Dick DM, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Suvisaari J, Viken RJ, Rose RJ, et al. Genetic correlation and gene--environment interaction between alcohol problems and educational level in young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:210. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latvala A, Rose RJ, Pulkkinen L, Dick DM, Korhonen T, Kaprio J. Drinking, smoking, and educational achievement: Cross-lagged associations from adolescence to adulthood. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2014;137:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Powdthavee N. Does more education lead to better health habits? Evidence from the school reforms in Australia. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;127:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg S, Pollak RA, Stearns JE. Family Inequality: Diverging Patterns in Marriage, Cohabitation, and Childbearing. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundborg P. The health returns to schooling---what can we learn from twins? Journal of population economics. 2013;26:673–701. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JL, von Hippel PT. An education gradient in health, a health gradient in education, or a confounded gradient in both? Social Science & Medicine. 2016;154:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis R. Educational Differences in Healthy Behavior Changes and Adherence Among Middle-aged Americans. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013;54:353–368. doi: 10.1177/0022146513489312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffery JM, Papandonatos GD, Lyons MJ, Koenen KC, Tsuang MT, Niaura R. Educational attainment, smoking initiation and lifetime nicotine dependence among male Vietnam-era twins. Psychological medicine. 2008;38:1287–1297. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezuk B, Myers JM, Kendler KS. Integrating social science and behavioral genetics: testing the origin of socioeconomic disparities in depression using a genetically informed design. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:S145–S151. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Education and self-rated health cumulative advantage and its rising importance. Research on Aging. 2008;30:93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Røysamb E, Jacobson K. Multivariate genetic analysis of sex limitation and G× E interaction. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2006;9:481–489. doi: 10.1375/183242706778024937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okbay A, Beauchamp JP, Fontana MA, Lee JJ, Pers TH, Rietveld CA, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 74 loci associated with educational attainment. Nature. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nature17671. advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. PISA 2012 Results: Excellence Through Equity: Giving Every Student the Chance to Succeed (Volume II) 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, Mullan JT. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981:337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninkilampi-Kerola V, Kaprio J, Moilanen I, Rose RJ. Co-twin dependence modifies heritability of abstinence and alcohol use: a population-based study of Finnish twins. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2005;8:232–244. doi: 10.1375/1832427054253095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli A, Marangoni F, Avogaro A, Barba G, Bellentani S, Bucci M, et al. Moderate alcohol use and health: A consensus document. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2013;23:487–504. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S. Variance components models for gene--environment interaction in twin analysis. Twin Research. 2002;5:554–571. doi: 10.1375/136905202762342026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. The Lancet. 2009;373:2223–2233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose RJ, Dick DM, Viken RJ, Kaprio J. Gene-environment interaction in patterns of adolescent drinking: Regional residency moderates longitudinal influences on alcohol use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:637–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Refining the association between education and health: the effects of quantity, credential, and selectivity. Demography. 1999;36:445–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Wu C-l. The links between education and health. American sociological review. 1995:719–745. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarna S, Kaprio J, Sistonen P, Koskenvuo M. Diagnosis of twin zygosity by mailed questionnaire. Human heredity. 1978;28:241–254. doi: 10.1159/000152964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan MJ, Hofer SM. Social context in gene--environment interactions: Retrospect and prospect. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60:65–76. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey P. An alternative approach to addressing selection into and out of social settings neighborhood change and African American children’s economic outcomes. Sociological Methods & Research. 2012;41:251–293. [Google Scholar]

- Sipilä P, Rose RJ, Kaprio J. Drinking and mortality: long-term follow-up of drinking-discordant twin pairs. Addiction. 2016;111:245–254. doi: 10.1111/add.13152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L. Social Capital and Psychological Distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2011;52:478–492. doi: 10.1177/0022146511411921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South SC, Hamdi N, Krueger RF. Biometric modeling of gene-environment interplay: The intersection of theory and method and applications for social inequality. Journal of personality. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jopy.12231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South SC, Krueger RF. Genetic and environmental influences on internalizing psychopathology vary as a function of economic status. Psychological medicine. 2011;41:107–117. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake DS, Hopfer CJ, Rhee SH, Friedman NP, Haberstick BC, Lessem JM, et al. College attendance and its effect on drinking behaviors in a longitudinal study of adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1020–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker-Drob EM, Bates TC. Large Cross-National Differences in Gene × Socioeconomic Status Interaction on Intelligence. Psychological science. 2016;27:138–149. doi: 10.1177/0956797615612727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkheimer E, Haley A, Waldron M, D’Onofrio B, Gottesman II. Socioeconomic status modifies heritability of IQ in young children. Psychological science. 2003;14:623–628. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Avison WR. Status variations in stress exposure: Implications for the interpretation of research on race, socioeconomic status, and gender. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003:488–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sluis S, Posthuma D, Dolan CV. A note on false positives and power in GxE modelling of twin data. Behavior genetics. 2012;42:170–186. doi: 10.1007/s10519-011-9480-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group, editor. World Development Indicators 2016. World Bank Publications; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health, 2014. 2014