Abstract

Efficient self-regulation of alertness declines with age exacerbating normal declines in performance across multiple cognitive domains, including learning and skill acquisition. Previous cognitive intervention studies have shown that it is possible to enhance alertness in patients with acquired brain injury and marked attention impairments, and that this benefit generalizes to improvements in more global cognitive functions. In the current preliminary studies, we sought to test whether this approach, that targets both tonic (over a period of minutes) and phasic (moment-to-moment) alertness, can improve key executive functioning declines in older adults, and enhance the rate of skill acquisition. The results of both experiments 1 and 2 demonstrate that, compared to active control training, alertness training significantly enhanced performance in several validated executive function measures. In experiment 2, alertness training significantly improved skill acquisition compared to active control training in a well-characterized speed of processing task, with the largest benefits shown in the most challenging speed of processing blocks. The results of the current study suggest that targeting intrinsic alertness in cognitive training provides a novel approach to improve executive functions in older adults and may be a useful adjunct treatment to enhance benefits gained in other clinically validated treatments.

Introduction

Age-related cognitive decline affects multiple aspects of cognition (Baltes & Lindenberger, 1997; Nilsson, 2003; Salthouse, 1996) such as executive functioning (Coppin et al., 2006; Royall et al., 2004) and processing speed (Salthouse, 2000; Schneider & Pichora-Fuller, 2000; Yakhno et al., 2007), negatively impacting memory (Nilsson, 2003; Salthouse, 2003) and the potential for new learning (e.g., skill acquisition). Many of these declining cognitive operations are modulated by the quality of cognitive alertness, the control of which also declines with age (e.g., sustained attention; McAvinue et al., 2012) resulting in increased lapses of attention, greater fall risk and motor vehicle accidents (Burdick et al., 2005; Cahn-Weiner et al., 2000; Conlon & Herkes, 2008; Hertzog et al., 2008; Salthouse, 2012; Smilek et al., 2010). In fact, the ability to maintain an alert state of response readiness is an objective cognitive marker of frailty progression in older adults (O’Halloran et al., 2013), suggesting a link between cognitive alertness and physical vigor.

The ability to maintain an alert and ready state is fundamental for higher order cognitive operations (Cahn-Weiner et al., 2000; Kempermann et al., 2002; Owsley & McGwin, 2004) and is dependent on efficient neuromodulatory control (Aston-Jones et al., 1999; Bao, Chan, & Merzenich, 2001; Robertson, 2014, Acevedo & Loewenstein, 2007; Elrod et al., 1997; Jones et al., 2006). Specifically, functions related to alertness have been characterized as tonic or phasic in nature (see Aston-Jones & Cohen, 2005). Tonic or sustained alertness, refers to the ongoing state of intrinsic readiness (over minutes) that provides the cognitive tone necessary for efficient cognitive function (Posner, 2008; Raz & Buhle, 2006; Sturm et al., 1999). Phasic alertness is the rapid modulation of attention due to a briefly engaging event (extrinsic) or meaningful cue (intrinsic) (McIntire et al., 2006; Posner, 2008; Sturm et al., 1999; Van Vleet & Robertson, 2006) and is vital to selective attention (Finke et al., 2012; Husain & Rorden, 2003; Sturm & Willmes, 2001). Together, tonic and phasic alertness, support an engaged and sustained state of attention critical for optimal spatial awareness (Manly, Dobler, Dodds, & George, 2005), memory encoding and retrieval (Yoo, Hu, Gujar, Jolesz, & Walker, 2007), and learning (Seitz & Watanabe, 2005). Normal aging is marked by decline in the efficiency of tonic and phasic alertness, as older adults perform significantly worse than younger adults in tasks that target these functions (Andrés et al., 2006; Conlon & Herkes, 2008; Festa-Martino, Ott, & Heindel, 2004; Georgiou-Karistianis et al., 2007; Jennings et al., 2007; Lahar et al., 2001).

A number of therapeutic approaches to improve age-related cognitive decline have been developed, though there is little consensus regarding the best approach. For example, interventions have targeted compensatory strategies (e.g., mnemonic memory aids; Kliegel & Bürki, 2012), working memory skills (Jaeggi et al., 2008; Verhaeghen & Basak, 2005), speed of processing (Karlene Ball et al., 2002; Wolinsky et al., 2013), perceptual learning (Anand et al., 2011; Mahncke et al., 2006), and multitasking (Anguera et al., 2013) among others (Strenziok et al., 2014). However, few cognitive training approaches have directly targeted alertness in older adults (Milewski-Lopez et al., 2014). Methods for bolstering alertness, such as the use of brief warning tones (Posner, 2008; Robertson et al., 1998) or self-initiated reminders (O’Connell et al., 2008) to improve focused attention have been shown to transiently improve participants’ reaction time and perceptual resolution (Matthias et al., 2010), though their long term effects are unclear. Further, approaches that rely on self-initiated reminders may not be effective in older adults with poor memory (e.g., mild cognitive impairment) (Milewski-Lopez et al., 2014). Semi-structured practice, such as meditation training (e.g., mindfulness meditation, focused meditation) has shown enhancement of alertness in some cases (Tang et al., 2007), though not all (see Semple, 2010). Mindfulness as a method of enhancing alertness may be challenging for some individuals due to its reliance on meta-awareness, which may be compromised in those with age-related cognitive decline. In addition, many weeks of practice without objective indicators of progress may be required to yield improvement in alertness. Finally, pharmacological treatments such as the noradrenergic agonist modafinil have been shown useful for treating alertness impairments in sleep-deprived individuals (Repantis, Schlattmann, Laisney, & Heuser, 2010), but have shown less consistent effects in individuals who exhibit normal sleep patterns. Additionally, modafinil and other stimulant medications (Wigal, 2009) may cause unwanted side effects such as anxiety, headache and nausea.

Innovative approaches to computer-based cognitive training have shown promise to enhance alertness in individuals with severe alertness deficits due to acquired brain injury. In several studies, patients have shown sustained improvements in attention and executive functions (Degutis & Van Vleet, 2010; Thimm et al., 2006; Van Vleet et al., 2015; Van Vleet & DeGutis, 2013). For example, a treatment strategy that concurrently trains tonic and phasic aspects of alertness (Tonic and Phasic Alertness Training, TAPAT) has been shown to improve patients’ ability to sustain attention; benefits generalized to improvements in working memory, perception and visual search following short epochs of training (36 mins × 9 sessions) over 2-3 weeks (Degutis & Van Vleet, 2010; Van Vleet & DeGutis, 2013; Van Veet et al., 2015). Additionally, caregivers reported that training reduced patients’ spatial navigation errors and collisions, suggesting generalization to real-world functioning. Additional follow up studies of TAPAT have shown that patients with traumatic brain injury exhibit benefits in simple and complex attention that generalizes to performance on more difficult measures of executive function (e.g., multitasking, set switching, fluency; Van Vleet et al., 2015). As executive functions are largely dependent on brain areas that are especially prone to decline in older age (e.g., prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia; Ridderinkhof et al., 2004; Ridderinkhof & Wijnen, 2011; Treitz et al., 2007), we hypothesized that TAPAT training may also benefit older adults.

In the current preliminary studies, we first examined whether alertness training (TAPAT) would benefit attention and executive functions in older adults, similar to what has been previously shown in acquired brain injury. We hypothesized that older adults in the TAPAT group would show greater benefits in these cognitive domains relative to an active control group. Next, to examine the influence of alertness training on learning (i.e., skill acquisition), we examined progression in a well-characterized speed of processing (SOP) challenge over time with the goal of comparing magnitude of change in SOP attributable to TAPAT versus active control training. Performance in the SOP task is especially relevant to older adults, as this task has been shown related to driving safety (Ball et al., 2010; Edwards et al., 2009), mood (Wolinsky et al., 2009, 2010), functional efficiency (Ball et al., 2007; Edwards et al., 2005), quality of life and protection from further cognitive decline (e.g., 3-5 years of protection; Wolinsky et al., 2010, 2013). We hypothesized that older adults in the TAPAT versus the active control group would show faster progress in learning the task and would achieve a higher performance level by the end of training.

Experiment 1

1. Methods

1.1 Participants

Twenty-four healthy older adults, recruited from the San Francisco bay area gave informed consent before study participation in compliance with Western Institutional Review Board (Seattle, Washington) protocol WIRB20111223. Participants’ demographic information is shown in table 1. Twenty-one participants completed the study protocol (TAPAT group=11; AC=10) and received $200.00 compensation. Three participants withdrew early due to factors unrelated to the training (e.g., illness, travel); two were from the control group and one from the intervention group. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing and were screened for seizure disorder, psychiatric disorder, dementia, mild cognitive impairment or other neurological impairments, and substance abuse, all conditions that may occlude interpretation of the results (verified by interview). Also, all participants were screened for the presence of depression using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS; Yesavage et al., 1982) (all participants screened scored < 10 and were included) and general speed of processing using Trails A (performance of all participants screened was within two standard deviations of age and education matched norms in this task and were included in the study)(Tombaugh, 2004).

Table 1. Participant Demographics.

| N | Mean Age (SD) | Gender | Mean Years of Education (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | ||||

| TAPAT | 11 | 77 (7.5) | 6 males | 16.6 (2.5) |

| AC | 10 | 75 (8.5) | 5 males | 16.0 (2.9) |

| Experiment 2 | ||||

| TAPATSOP | 12 | 75 (6.3) | 8 males | 15.7 (1.7) |

| ACSOP | 12 | 74 (5.9) | 7 males | 14.0 (2.0) |

TAPAT = tonic and phasic alertness training; AC = active control training; SOP = speed of processing challenge; SD = standard deviation.

Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention (TAPAT) or active control training (AC) group and performance on standardized and experimental measures of attention and executive function was examined twenty-four hours prior to the initiation of training and within twenty-four hours following completion of five hours of training, see figure 1. The schedule of training was fixed for all participants and participants were allowed three weeks to complete all nine training sessions. In each session, participants were provided three 12-min blocks of training and time-in-training was restricted to 36 min per calendar day. Due to the importance of alertness in executive function (Chan, 2002; Chan et al., 2003; Cicerone, 1996; Felmingham et al., 2004; Ponsford & Kinsella, 1992; Spikman & van der Naalt, 2010; Stuss et al., 1989; Stuss et al., 1989), we hypothesized that improvement in the regulation of alertness due to TAPAT would also improve performance on more complex cognitive operations (e.g., working memory, set shifting, fluency).

Figure 1. Training timeline.

Visualization of the training timeline for experiments 1 and 2.

1.2 Stimuli and Training Procedures

Tonic and Phasic Alertness Training (TAPAT)

The goal of this training procedure was to foster prolonged focused task engagement. Participants were required to practice sustained response monitoring in the training task (tonic alertness) and response inhibition when presented with rare no-go, target trials (phasic alertness). To this end, TAPAT utilized a continuous performance task paradigm and included several key elements: 1) not-X format that required frequent responding, as well as inhibitory control (withhold response required 10% of trials), 2) jittered inter trial intervals, which have been shown to promote greater attentional engagement and response control in individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Ryan, Martin, Denckla, Mostofsky, & Mahone, 2010), and 3) novel stimuli, which have also been shown to engage attention (Downar, Crawley, Mikulis, & Davis, 2002)

In each session, participants were first presented with a unique target object to memorize (new target object was presented for each 12-min block). Target objects were unique to each block and were never presented as nontargets in subsequent blocks, nor in other training sessions. Participants self-initiated the task after memorizing the target and 360 images were presented at central fixation for a fixed duration of 500 msec and separated by a fixation cross shown at one of three randomly ordered inter stimulus intervals (ISI): 600, 1800 or 3000 msec. Images of objects were acquired from the Caltech 256 Object Category dataset (Griffin, Holub, & Perona, 2007) due to their diverse set of natural and artificial objects in various settings. Images comprised six categories (e.g., household items), each with nine image sets containing twenty-one unique items in each set. Each training session consisted of three 12-min blocks and participants completed nine sessions within three weeks (5.4 hours total training time). commission accuracy (accuracy at responding to non-targets), correct commission reaction time and reaction time variability, and omission accuracy (accuracy at withholding response to targets) for every 120 trials was collected. Given the results of prior TAPAT and related studies (Degutis & Van Vleet, 2010; Esterman et al., 2015; Esterman, Noonan, Rosenberg, & DeGutis, 2012) that indicated high correlation between RT variability (tonic) and target accuracy (phasic), we chose to evaluate changes in target accuracy (provided > 90% commission accuracy) over training to determine improvement for each participant.

Active Control Training (AC)

The active control (AC) training paradigm was well matched with the intervention (Jacoby & Ahissar, 2012) and was employed successfully in a prior study that showed that the task was equivalent to TAPAT with respect to its effects on physiological arousal (Van Vleet, Hoang-duc, DeGutis, & Robertson, 2011). The task included the same stimuli as TAPAT, required the same time-on-task per session (3 × 12-minute blocks) and was equated for frequency and duration of contact with the experimenter as the intervention group. Participants were required to engage in a serial categorization task in which they were required to judge the spatial orientation (“tilted left or right”) of the same images of objects used in TAPAT training. Images were presented sequentially at central fixation and participants were required to execute a response at the end of each block (‘left’ or ‘right’) indicating that the majority of the images shown were tilted to the left or right. Notably, the AC task did not involve elements considered part of the therapeutic process (i.e., did not require continuous responding or tonic alertness, and did not require interruption of responses or phasic alertness).

Both training tasks employed fixed parameters (i.e., non adaptive) and were presented on an LCD panel (33 cm × 21 cm) of a laptop computer. Screen resolution was 1280 by 800 pixels and the refresh rate was 60 Hz. Participants viewed stimuli from a distance of 60-70 cm, with their line of sight perpendicular to the LCD screen. During training, participants responded via spacebar press (TAPAT) or the left or right arrow (AC) with their dominant hand.

1.3 Outcome Measures

The goal of experiment 1 was to determine if TAPAT, compared to AC, improved performance in executive functions that were not considered the explicit focus of training (e.g., working memory, set shifting, fluency). As in prior TAPAT training studies, we also examined related benefits in attention. Performance on standardized and experimental measures of attention and executive function was examined one day prior to initiation of training and within twenty-four hours post completion of nine sessions of either TAPAT or AC. Performance in the letter-number sequencing, trails b and controlled oral word association tasks was compared to age and education (where available) matched norms (Strauss, Sherman & Spreen, 2006) and transformed to z scores.

Attention: Attentional Blink task (AB)

The attentional blink (AB) is a visual attention task in which participants must detect and recognize two target numbers interspersed in a rapid serial visual presentation of fourteen black letters subtending 2° of visual angle vertically and 1° horizontally at central fixation (see Raymond et al., 1992; Shapiro et al., 1994). Each character was presented on the screen for 80 msec with a 20 msec inter stimulus interval and the first of two target numbers (T1) was shown in red to maximize identification while the second target number (T2) was black. T2 appeared at one of two temporal positions following the presentation of T1 (lag 2 or 200msec after T1 offset; lag 6 or 600msec after T1 offset). Participants verbally reported the identity of the two targets (experimenter coded responses via keyboard) and the dependent variable was the percent T2 accuracy, given correct identification of T1. Trials in which T1 was not correctly identified were not included in the analysis. The AB task has been employed in prior cognitive training studies of TAPAT (DeGutis & Van Vleet, 2010; Van Vleet et al., 2015; Van Vleet & DeGutis, 2013). Age-related decline in the efficiency of tonic and phasic alertness has been shown to influence selective attention (Nieuwenhuis, Aston-Jones, & Cohen, 2005) and several studies have shown that older participants perform significantly worse than younger participants in this task (Conlon & Herkes, 2008; Georgiou-Karistianis et al., 2007; Lahar et al., 2001; Mahncke et al., 2006).

Working Memory Span: Letter Number Sequencing Task (LNS)

The LNS task from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III is a verbal working memory span task that required participants to internally re-order intermingled letters-number sets verbally presented by the experimenter and retrieve them from verbal short-term memory. The dependent variable used in the current study was the total number of correctly recalled and reordered letter-number sets. Older adults generally experience greater working memory declines compared to younger adults, even when accounting for age-related generalized cognitive slowing (Bherer et al., 2005, 2008; Verhaeghen & Basak, 2005).

Set Shifting: Trail Making Test (Trails B)

Trails B was used to assess visual scanning ability, processing speed, and set-shifting (an executive function). The dependent variable was the number of seconds required to correctly complete the connection of numbers (Trails A) or number-letter sets (Trails B) (Arnett & Labovitz, 1995).

Verbal Fluency: Controlled Oral Word Association Task (COWAT)

COWAT is a phonemic cued verbal fluency task in which participants are required to spontaneously and rapidly generate unique words to a letter cue (e.g., C, F or L). The dependent variable was the total number of correct words generated in sixty seconds in each of three trials. The generation of words on the basis of orthographic criteria requires spontaneous implementation of a nonhabitual strategy, efficient organization of verbal retrieval, effortful self-initiation and good self-monitoring (i.e., the participant must keep track of responses already given and inhibit inappropriate responses), all of which are vulnerable cognitive functions in older adults. An alternate form of this task was employed at baseline (CFL) versus post-training assessment (PRW) (Ross et al., 2006).

1.4 Data Analysis

The main goal of experiment 1 was to measure the impact of TAPAT training versus AC in older adults using standard and experimental measures of attention, working memory and executive function; domains that were not the explicit focus of training. To account for potential type I errors associated with analyzing multiple measures, our main analyses utilized repeated measures between groups (TAPAT/AC) multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), as this approach has been shown more powerful at detecting group differences than performing many individual ANOVAs. Significant group x pre/post MANOVAs were followed up with ANCOVAs evaluating performance in individual measures corrected for multiple comparisons using a false discovery rate per Benjamini and Hochberg (1995). This approach has shown to be more powerful than a repeated measures ANOVA approach and preferable for smaller cohorts, such as in the current study (Van Breukelen, 2006). To understand whether individual differences in baseline performance in the assessments or improvement in TAPAT training were related to post training performance improvements, we performed correlation analyses using a false discovery rate of p = 0.05. For outcome measures with multiple significant predictors, we ran linear regressions with the predictors entered simultaneously using a false discovery rate of p = 0.05..

2. Results

2.1 Behavior

2.1.1 Baseline

We first compared participants in the TAPAT and AC groups at baseline to ensure that group differences post training were not due to disparities in demographics or performance in the neuropsychological measures at baseline. Table 1 contains the group means for the background characteristics by training group. At baseline (table 2), there was no difference between TAPAT and AC groups in age [t (1,19) = −0.26, p = 0.78], education [t (1,19) = −.54, p = 0.59], mood (GDS) [t (1,19) = −0.26, p = 0.78] or performance in the COWAT [t (1,19) = 1.50, p = 0.15], Trails B [t (1,19) = 0.12, p = 0.91], LNS [t (1,19) = 0.95, p = 0.35] or AB [t (1,19) = −0.02, p = 0.98]. Performance in all neuropsychological measures across groups was within two standard deviations of the age and education normative values established for each measure (Strauss, Sherman, & Spreen, 2006).

Table 2. Baseline Performance and Training.

|

AB Accuracy (SD) |

COWAT Z score (SD) |

LNS Z score (SD) |

Trails B Z score (SD) |

Trails B-A Mean RT (SD) |

Training: First Session Accuracy (SD) RT (SD) |

Training: Last Session – First Session Accuracy (SD) RT (SD) |

|

| Experiment 1 | |||||||

| TAPAT | .21 (.15) | .00 (.97) | .14 (.56) | −.32 (.85) |

75.4 (56.5) |

67.0 (10.2) 507.0 (45.2) |

12.4 (4.0) −32.2 (33.5) |

| AC | .29 (.24) | .56 (1.2) | .26 (.95) | .11 (.76) | 68.5 (42.5) |

88.2 (12.0) 1183.5 (655.4) |

6.0 (6.0) −42.4 (43.1) |

|

SOP outcome Trial Duration (SD) |

D-KEFS VF Switch Z score (SD) |

Design Fluency -Switch Z score (SD) |

Trails B Z score (SD) |

Trails B-A Mean RT (SD) |

Training: First Session Accuracy (SD) RT (SD) |

Training: Last Session – First Session Accuracy (SD) RT (SD) |

|

| Experiment 2 | |||||||

| TAPATSOP | 823.2 (170.1) |

.05 (1.20) |

.44 (.47) | −.20 (1.09) |

70.71 (39.0) |

61.3 (26.4) 551.7 (165.6) |

13.5 (20.2) −13.3 (8.0) |

| ACSOP | 763.2 (191.0) |

.50 (1.19) |

1.05 (1.04) |

.49 (.63) | 57.69 (35.4) |

89.4 (14.4) 1248.3 (548.5) |

7.5 (12.2) −50.3 (33.0) |

2.1.2 Training

There was no difference between TAPAT (mean = 315.0 min, SD = 38.2 min) versus AC (mean = 322.0 min, SD = 24.4 min) groups in total training time (p > 0.05). As shown in prior studies (DeGutis & Van Vleet, 2010; Van Vleet et al., 2015; Van Vleet & DeGutis, 2013), participants in the TAPAT group in the current study improved over time (see table 2). Specifically, change in target accuracy in session 9 versus session 1 was significant [t (10) = −11.34, p < 0.01], but RT in session 9 versus session 1 was not [t (10) = 0.70, p = 0.50]. Also, to ensure that participants in the AC group were highly engaged with the control task, we evaluated changes in reaction time and accuracy over time. Participants in the AC group improved in target accuracy in session 9 versus session 1 [t (9) = 8.07, p < 0.001], but not RT [t (9) = 1.27, p = 0.24].

2.1.3 Outcomes

To address the main aim of experiment 1 (i.e., determine if there was an effect of TAPAT versus active control in executive functions) we performed a repeated-measures MANOVA using the following four outcome measures, working memory span (LNS), selective attention (AB), verbal fluency (COWAT) and set shifting (Trails B) as dependent variables and Time (pre/post) x Group (TAPAT/AC) as factors. The MANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Time [F(1,19) = 12.75, p < 0.01, Wilks’ λ = 0.60] and a significant overall Time x Group interaction [F(1,19) = 30.50, p < 0.0001, Wilks’ λ = 0.38], suggesting that training had a significant overall effect on these outcome measures; main effect of Group was not significant [F(1,19) = 0.47, p = 0.50]. This effect was driven by generally improved performance on all four measures in the TAPAT group after training. To assess the significance of each measure, we performed between-groups univariate ANCOVAs for each of the four measures, evaluating performance on each measure post-training while controlling for baseline performance (pre-training). We corrected for multiple comparisons using a false discovery rate of p = 0.0375, per Benjamini and Hochberg (1995). Results are presented by measure below.

Selective Attention: AB

A between-groups (TAPAT, AC) univariate ANCOVA of post training AB performance (mean T2 accuracy at lags 2 + 6), controlling for pre training performance, revealed a significant group difference (F (1,21) = 37.18, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.68) driven by greater performance in the TAPAT group (mean = 48.6%, SD 11.5%) relative to the AC group (mean = 32%, SD 21.7%). Performance in the AB post training was highly correlated with baseline performance [r = −0.65, n = 11, p = 0.03] indicating that participants with the worst performance in the AB, showed the greatest improvements. Finally, improvement in the training task (i.e., target accuracy in the TAPAT task: session 9 – session 1) was not correlated with improvements (post-pre) in the AB task (p > 0.05).

Verbal Fluency: COWAT

A between-groups (TAPAT, AC) univariate ANCOVA of post training COWAT performance, controlling for pre training performance, revealed a significant group difference (F (1,21) = 65.03, p < 0.0001, partial η2 = 0.78) driven by greater performance in the TAPAT group (mean = 1.01, SD 0.76) relative to the AC group (mean = 0.27, SD 1.17) in number of unique words spontaneously generated to phonemic cues. The number of unique words generated post training was highly correlated with the number of unique words generated before training [r = −0.74, n = 11, p = 0.01] indicating that participants with the worst performance on the COWAT showed the greatest improvements. Also, improvement in the training task was correlated with improvements (post-pre) in the COWAT task (r = 0.60, n = 11, p = 0.05). Given multiple significant correlations, we ran a linear regression predicting COWAT improvement in which baseline COWAT performance and TAPAT training improvement were entered simultaneously as predictors. The overall model was significant [F (2,8) = 8.94, p < 0.01) with an R2 of 0.691, and interestingly only baseline COWAT performance significantly uniquely predicted COWAT improvement, while TAPAT training improvement only showed a trend to uniquely predicting COWAT improvement.

Working Memory: LNS

A between-groups (TAPAT, AC) univariate ANCOVA of post training LNS performance, controlling for pre training performance, revealed a significant group difference (F (1,21) = 23.46, p < 0.0001, partial η2 = 0.57) driven by greater performance in the TAPAT group (mean = 1.15, SD 0.60) relative to the AC group (mean = 0.20, SD 0.77) in working memory span. Baseline LNS performance was not correlated with magnitude of benefit post training (p > 0.05) and improvements in the training task were not related to improvements in LNS (p > 0.05).

Set Shifting: Trails B

A between-groups (TAPAT, AC) univariate ANCOVA of post training Trails performance (Trails B), controlling for pre training performance, did not reveal a between group difference (F (1,21) = 1.31, p = 0.27).

3. Discussion

In experiment 1, we examined the effects of an alertness training program to improve executive functions in healthy older adults. Following 5.4 hours of training, participants in the TAPAT training group showed significant improvements in executive functions compared to participants that trained on a closely matched active control training condition (AC group). The results show that improvements in alertness, as evidenced by increased target accuracy in the TAPAT training task, generalized to performance in domains that were not considered the explicit focus of training. Thus, benefits of TAPAT cannot be characterized as merely ‘training to the test’. Further, improvements in target accuracy in TAPAT, indicative of better performance and better intrinsic alertness (Cheyne et al., 2006; Christoff et al., 2009; Hester & Garavan, 2005; Manly et al., 1999; Robertson et al., 1996; Smallwood et al., 2004; Smallwood et al., 2008), were highly correlated with improvements in verbal fluency and selective attention (COWAT, AB). Whereas, simply engaging in a challenging continuous performance task (TAPAT) versus an active control was sufficient to improve working memory span (LNS). The results are consistent with recent studies in which patients with acquired brain injury also benefitted from TAPAT training (Degutis & Van Vleet, 2010; Van Vleet et al., 2015, 2011; Van Vleet & DeGutis, 2013). Together, these studies suggest that improved intrinsic regulation of alertness can improve attention and executive function.

The beneficial results of TAPAT training are likely due to enhancement of intrinsic, task-related alertness rather than extrinsic alertness driven by stimulus novelty (Downar et al., 2002), as participants in the AC group were exposed to the same novel stimuli as TAPAT. Also, the benefits of TAPAT versus AC are not better explained by differences in physiological arousal, as a prior study from our lab demonstrated that performance on several physiological indices of arousal did not differ between an object categorization control task, similar to the AC task in the current study, and TAPAT (Van Vleet et al., 2011). Rather, the therapeutic effects of TAPAT may be due to self-generation of a more optimal state of attention, which has been described by Aston-Jones and Cohen as an exploitative or phasic mode of attention (Aston-Jones & Cohen, 2005). In this state, participants exhibit large phasic responses to salient (i.e., behaviorally relevant) stimuli. In experiment 1, improvements in the attentional blink (AB) task in the TAPAT relative to the AC group may reflect greater time in phasic mode (Usher et al., 1999).

In summary, TAPAT training versus a closely matched active control training condition, benefitted attention and executive functions in older adults. Notably, significant improvements in LNS, a verbal working memory task with a multitasking component in which participants were required to internally switch between categories (i.e., re-ordering and recalling numbers versus letters in proper sequence) suggested improvement in set switching. However, a shortcoming of experiment 1 is the absence of an explicit set-switching measure. Further, the interpretation of the null effect in the explicit psychomotor switch task employed in experiment 1 (Trails B) was challenging, as fine motor skill was compromised in a subset of participants.

Experiment Two

4. Methods

4.1 Design

In experiment 2, we sought to expand upon the results of the initial experiment by examining the potential impact of alertness training on learning over time. Our hypothesis in experiment 2 was that TAPAT training, by improving alertness, would also improve learning (rate and/or asymptotic level achieved) of a novel task. Specifically, we examined progression in a well-characterized speed of processing task (Ball et al., 1988), which was delivered in a manner consistent with recent work by Wolinsky et al. (2013) (e.g., trial duration was adapted to performance and stimulus sets were progressively more challenging across sessions). We chose this task due to its extensive characterization in healthy aging studies and the important implications of performance in this task in real-world outcomes in older adults. Speed of processing has been shown to have direct implications for driving safety (Ball et al., 2010; Edwards et al., 2009), functional efficiency, quality of life (Wolinsky et al., 2010) and protection from further cognitive decline (Wolinsky et al., 2013). Given that within-session effects of TAPAT have been shown ephemeral (Van Vleet et al., 2011), we did not expect differences in learning between groups to emerge until the dosage of TAPAT exceeded ~5 hours, as shown previously (DeGutis & Van Vleet, 2010; Van Vleet et al., 2015; Van Vleet & DeGutis, 2013). Also, given prior reports, we hypothesized that learning the UFOV task may progress incrementally and may require several hours of engagement to show significant changes from baseline. Thus, to better facilitate this comparison between groups, we extended the training period to twelve hours to ensure that we effectively captured TAPAT and UFOV-related changes.

In experiment 2, we also included a different set of measures to ensure that the effects observed in experiment 1 were not specific to the particular executive functions tasks employed. We also sought to further examine set switching performance (see experiment 1 Discussion) while controlling for fine motor speed and skill across groups. Prior to training, participants were evaluated to ensure equivalent ability between groups on Trails A, as in experiment 1, and grooved pegboard performance. We also administered the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) to assess verbal neurocognitive functioning and to estimate premorbid IQ (Green et al., 2008). Finally, to evaluate persistence of benefits from an initial training experience, participants were re-assessed following a no-contact period of six weeks following completion of training.

4.2 Participants

Twenty-eight healthy older adults recruited from the San Francisco bay area gave informed consent before study participation in compliance with Western Institutional Review Board (Seattle, Washington) protocol: WIRB20111223. Participants’ demographic information is shown in table 1. Four participants withdrew early due to factors unrelated to the study (e.g., relocation, illness); two from the intervention group and two from the control group. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing and were screened for seizure disorder, dementia or other neurological impairments, and substance abuse history that may occlude interpretation of the results (verified by interview). Also, all participants were screened for the presence of depression using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (all participants screened scored < 10 and all were included), premorbid intelligence (WTAR; no between group difference, p > 0.05) and motor function including general speed of processing using Trails A and motor coordination using the grooved pegboard task (performance of all participants screened was within two standard deviations of age and education matched norms and all were included in the study). Participants received $200.00 upon completion of the study.

Participants were randomly assigned to either twelve hours of alertness training and speed of processing (SOP) challenge, TAPATSOP (12 min SOP > 12 min TAPAT > 12 min TAPAT), or active control (AC) and speed of processing challenge, ACSOP (12 min SOP > 12 min AC > 12 min AC); see figure 1. As in experiment 1, performance on standardized and experimental measures of attention, working memory and executive function was examined twenty-four hours prior to the initiation of training and within twenty-four hours following completion of training. In experiment 2, participants were also re-evaluated following a six-week no-contact period to examine persistence of the training effects. Given the importance of alertness in learning, we hypothesized that improvement in the regulation of alertness due to TAPAT would improve performance and progression in the SOP task relative to control.

4.3 Stimuli and Training Procedures

Total training time was greater in experiment 2 (12 hours vs. 5.4 hours) than experiment 1 in order to: 1) incorporate SOP challenge each session; 2) ensure sufficient dosage of an initial training period to evaluate persistence of benefits following a six week no contact period; and 3) effectively evaluate effects of TAPAT on SOP. Regarding the last point, we hypothesized that the influence of TAPAT on SOP may be subtle and may occur only after sufficient time-in-training, as previously shown (~ 5 hours, DeGutis & Van Vleet, 2010; Van Vleet et al., 2015; Van Vleet & DeGutis, 2013). The schedule of training was fixed for all participants and participants were allowed six weeks to complete all twenty-one training sessions. In each session, participants were provided three 12-min blocks of training and time-in-training was restricted to 36 min per calendar day.

TAPAT and Active Control

As in prior studies of TAPAT (Van Vleet et al., 2011; Van Vleet et al., 2015), and in experiment 1, stimuli included in both TAPAT and AC training blocks were drawn from images of objects from the Caltech 256 Object Category dataset (Griffin, Holub, & Perona, 2007) due to their diverse set of natural and artificial objects in various settings. Due to the relatively longer training period in experiment 2, an additional six categories (e.g., automobiles) were added to the array of images used in experiment 1 (see Methods experiment 1) to equate stimulus novelty across experiments.

Speed of processing challenge

We utilized a version of the UFOV task employed in recent studies (see Wolinsky et al., 2013). In each trial, a target item was briefly presented to the participant at central fixation (e.g., car or truck), while eight peripheral locations surrounding it were masked. Following presentation of the target and subsequent mask, the target was shown with a foil and participants were required to identify the target item (two-alternative forced choice). Simultaneously, the eight masked circular locations were replaced with seven distracter stimuli (e.g., ‘rabbit crossing’ signs) and a target stimulus (always a ‘Route 66’ sign). The participant was first required to select the correct target vehicle at central fixation before selecting the circular location where the target sign appeared. Processing speed was challenged by progressively reducing the exposure duration of centrally and peripherally presented targets to maintain a 75% success rate at the current challenge level before reducing the duration. In addition, throughout the course of training, the eccentricity of peripheral target locations increased, as well as the number of distracters (up to 47) increasing the serial search difficulty. Centrally presented targets were also increasingly morphed (nine stages) to increase discrimination difficultly. The dependent variable or threshold score was the average exposure duration in milliseconds per session.

4.3 Outcome measures

Performance in standard measures of executive function and speed of processing (detailed below) was examined one day prior to TAPATSOP or ACSOP training, within twenty-four hours post completion of training and again following a six-week no-contact period.

Executive functions

To better capture set switching performance, we utilized the D-KEFS verbal fluency task. Similar to the COWAT employed in experiment 1, this task is comprised of speeded generative fluency tasks (e.g., generate words to phonetic or semantic cues), but unlike the COWAT, also included a speeded category-switching subtest (i.e., participants were required to switch between two semantic categories when producing words). To examine the effects of training on executive function/set switching, the dependent variable was the total number of accurate category switches or total number of words generated to the switch cues. Alternate forms of this task were employed at baseline versus the post-training assessments. We also employed the D-KEFS Design Fluency task (Delis, Kaplan, & Kramer, 2001) to examine visuographic fluency and set switching. In this task, participants were required to create unique designs using only four connected lines drawn within a random array of dots as anchor points. The dependent variable was the total number of unique designs generated in one minute when switching between filled versus open dots required to create the designs (i.e., switching subtask). Finally, as in experiment 1, we examined performance in Trails B and the dependent variable was the number of seconds required to correctly complete the connection of a number-letter set (Trails B)(Arnett & Labovitz, 1995). Unlike experiment 1, participants in experiment 2 were well matched across groups on measures of motor speed (Trails A) and fine motor coordination (grooved pegboard task). Performance in the verbal fluency switching, design fluency switching and trails b tasks was compared to age and education (where available) matched norms and transformed to z scores.

Speed of processing assessment

A standard SOP assessment measure, the useful field of view task (UFOV; Kathleen Ball & Owsley, 1993; Edwards et al., 2005), was employed at pre-training, post-training and follow-up. The SOP assessment required accurate stimulus identification, divided attention and selective attention, and possible scores ranged from 51–1500 ms reflecting the shortest exposure time at which the participant could correctly complete the task. The dependent variable, determined via psychophysical threshold procedure, was the trial duration necessary for 75% accuracy (see Edwards et al., 2005). Lower thresholds indicated better performance (i.e., ability to quickly and accurately identify the central target while also accurately locating the position of peripheral target).

4.4 Data Analysis

The goal of experiment 2 was to: a) further evaluate the impact of TAPAT training versus AC on executive function/set switching; and b) evaluate the influence of TAPAT on learning over time. As in experiment 1, to account for potential type I errors associated with analyzing multiple measures, our main analyses utilized repeated measures between groups multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Significant group x pre/post MANOVAs were followed up with ANCOVAs evaluating performance in individual measures corrected for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). To understand whether individual differences in baseline performance or TAPAT training improvements were related to assessment improvements, we performed correlation analyses using a false discovery rate of p = 0.05. For outcome measures with multiple significant predictors, we ran linear regressions with the predictors entered simultaneously using a false discovery rate of p = 0.05.

The other aim of experiment 2 was to evaluate the influence of TAPAT on learning over time. Theoretically, prior TAPAT studies have shown that the effects of training accumulate over ~5 hours (DeGutis & Van Vleet, 2010; Van Vleet et al., 2015; Van Vleet & DeGutis, 2013). Thus, we did not expect a difference between groups before this time point and split the analysis into early (sessions 1-10) and late training epochs (sessions 11-21). Also, we wanted to ensure that the potential effects of TAPAT vs. active control were not attributable to a transitory boost in alertness, as previously shown in similarly naïve participants during an initial training period (see Van Vleet et al., 2011); thus, we administered the learning task prior to TAPAT in each session.

To investigate whether early period training (sessions 1-10) and late period training (sessions 11-21) differed significantly by group, we used a generalized estimating equations (GEE) method. In particular, a linear spline variable representing the slope of the outcome over times 1-10 (early training), a second linear spline variable representing the slope of the outcome over times 11-21 (later training), and the interactions of group membership with the two spline terms. These interaction effects were the focal effects of interest in this analysis. We hypothesized that the interaction between group and the first spline term would be non-significant, indicating no significant differences between the two groups in the early phase of training (false discovery rate of p = 0.05). We also hypothesized that the interaction between group and the second spline term would be statistically significant, indicating a divergence between the two groups during the late phase of training when the TAPAT effect was evident (false discovery rate of p = 0.05). GEE was chosen as the analysis method to test these hypotheses because it yields consistent estimates of effects even if the working correlation structure among the repeated measures is misspecified (Zeger & Liang, 1986). Based on the recommendations in the literature for choosing a GEE correlation structure for longitudinal data (Allison, 2012), the M-dependent structure was used to estimate the working correlations. The GEE analysis was performed using SAS 9.4. For the two interaction terms of interest, we report the regression coefficient B, the Z-test of the null hypothesis that B=0 in the population, and the p-value associated with the Z-test.

5. Results

5.1 Behavior

5.1.1 Baseline

We first compared participants in the TAPATSOP and ACSOP groups at baseline to ensure that group differences post training were not due to disparities in demographics or performance in the neuropsychological measures at baseline (false discovery rate of p = 0.05). Table 1 contains the group means for the background characteristics by training group. At baseline (table 2), there was no difference between TAPATSOP and ACSOP groups in age [t (1,22) = 0.95, p = 0.35], education [t (1,22) = 0.38, p = 0.70], premorbid IQ estimate (WTAR) [t (1,22) = 0.36, p = 0.72], mood (GDS) [t (1,22) = 1.11, p = 0.27] or performance in verbal fluency switch task [t (1,22) = −0.91, p = 0.37], Trails B [t (1,22) = −1.70, p = 10.0], design fluency switch task [t (1,22) = −1.25, p = 0.10], and Speed of Processing/UFOV task [t (1,22) = 1.17, p = 0.13]. In addition, performance on all neuropsychological measures across groups was within two standard deviations of the age and education normative values established for each measure.

5.1.2 Training

There was no difference between TAPATSOP (mean = 496.0, SD = 11.3) and ACSOP (mean = 498.0, SD = 10.4) groups in total training time (p> 0.05). As shown in experiment 1 and in prior studies (DeGutis & Van Vleet, 2010; Van Vleet et al., 2015; Van Vleet & DeGutis, 2013), participants in the TAPATSOP group improved over training (see Table 2). Specifically, change in target accuracy session 21 versus session 1 was significant [t (11) = −2.99, p < 0.01], but RT session 21 versus session 1 was not [t (11) = 0.70, p = 0.50]. In addition, we evaluated TAPAT training performance in the first half (sessions 1- 10) versus the second half (sessions 11-21) of training and found a significant difference in target accuracy [t (18) = −6.11, p < 0.001], but not RT [t (18) = −0.13, p = 0.90].

To ensure that participants in the ACSOP group were highly engaged with the control task, we evaluated changes in reaction time and accuracy over time (see Table 2). Participants in the ACSOP group improved in target accuracy in session 21 versus session 1 [t (11) = 2.5, p < 0.03], but not RT [t (11) = 1.22, p = 0.25]. In addition, we evaluated control task performance in the first half (sessions 1- 10) versus the second half (sessions 11-21) of training and found a significant difference in target accuracy [t (18) = −4.17, p < 0.01], but not RT [t (18) = 0.39, p = 0.70].

5.1.3 Outcomes

We evaluated session-by-session progress (threshold in milliseconds) by group in the SOP challenge. The results of the generalized estimating equations (GEE) method yielded the following. The main effects for group (B = −31.05, Z = −0.53, p = .60) and the first spline term representing early training (B = 8.23, Z = 0.84, p = .40) were not significantly different from zero. However, the main effect for the second spline term representing later training epoch showed a significant negative slope (B = −39.58, Z = −3.60, p = .0003). As hypothesized, the interaction between group and the early training time spline was not statistically significant (B = 4.02, Z = 0.57, p = .57). However, the corresponding interaction between group and the later training time spline was significant (B = 16.73, Z = 2.18, p = .03). These results mirror the visual depiction of the congruence of the two groups’ trajectories in the early phase of training followed by their divergence in the later phases of training, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Experiment 2: Speed of Processing Challenge.

Graphical representations of mean performance in the speed of processing challenge (threshold / trial duration in milliseconds) by session and group. Shading represents standard error.

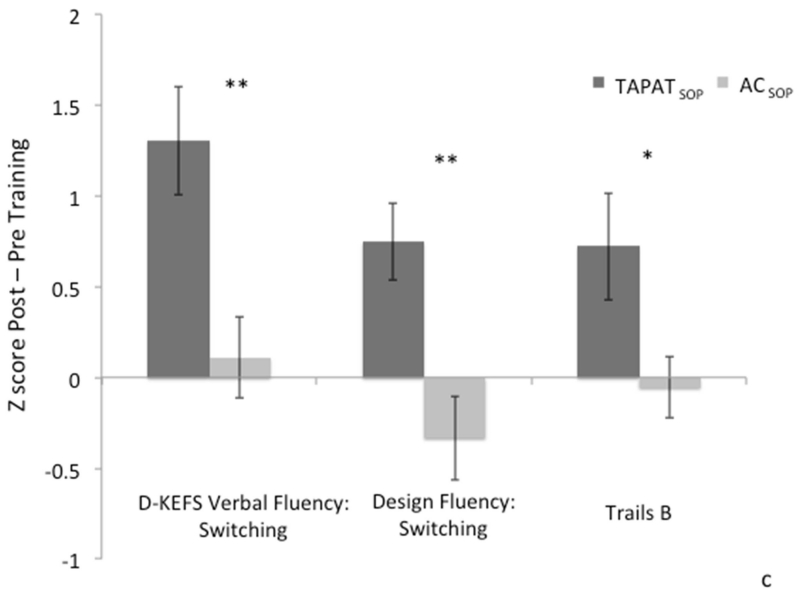

As in experiment 1, to determine if there was an effect of TAPATSOP training above and beyond active control and SOP training (ACSOP), we performed a repeated-measures MANOVA using the four outcome measures: spontaneous verbal and visuographic set shifting (D-KEFS verbal fluency switch task and D-KEFS Design Fluency switch task, respectively); Trails B; and the UFOV task. The four measures were included as dependent variables (Tests), and Time (pre/post) and Group (TAPATSOP, ACSOP) as factors. The MANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Time [F(2,20) = 37.27, p < 0.0001, Wilks’ λ = 0.22] and a significant Time x Group interaction [F(2,20) = 5.66, p < 0.01, Wilks’ λ = 0.65], suggesting that training had a significant overall effect on these outcome measures; main effect of group was non-significant [F(1,22) = 0.001, p < 0.98]. As can be seen in Figure 4a-d, this effect was driven by generally improved performance on all four measures in the TAPATSOP group after training. To assess the significance of each measure, we performed between-groups univariate ANCOVAs for each of the four measures, evaluating performance on each measure post-training while controlling for baseline performance (pre-training). We corrected for multiple comparisons using a false discovery rate of p = 0.0375, per Benjamini and Hochberg (1995). Results are presented by measure below.

Figure 4. Experiment 2: Executive Function and Speed of Processing Outcomes.

a) Change in performance (post – pre training) in the speed of processing outcome measure - the useful field of view task (UFOV) - by group. Error bars represent the standard error. b) Change in performance (post – pre training) in UFOV performance by participant. c) Change in performance in standardized neuropsychological measures of executive function that target set shifting (post – pre training) by group. Error bars represent the standard error. d) Change in executive function, composite score (comprising performance in verbal and visuographic set-shifting tasks and Trails B), post – pre training by participant. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Trails B

A between-groups (TAPATSOP, ACSOP) univariate ANCOVA of post training Trails B performance, controlling for pre training performance, revealed a significant between group difference (F (1,21) = 5.17, p < 0.03, partial η2 = 0.20) driven by greater performance in the TAPATSOP group (mean = 0.38, SD 0.62) relative to the AC group (mean = 0.18, SD 1.84) in time required to accurately switch between numbers and letters to complete the set. The amount of improvement in Trails B that participants demonstrated at post training was correlated with level of performance before training [r = −0.65, n = 12, p = 0.02] indicating that participants with the worst performance on Trails B showed the greatest improvements (see figure 5a). However, change in target accuracy in the TAPAT task (session 21 – session 1) was not correlated with improvements (post-pre) in Trails B (p > 0.05).

Figure 5a-d. Experiment 2: Correlations.

a) Correlation between performance improvement in Trails B (post – pre training) and baseline performance. b) Correlation between performance improvement in D-KEFS verbal fluency – switching (post – pre training) and improvement in TAPAT training task accuracy (last session – first session). c) Correlation between performance improvement in UFOV (post – pre training) and baseline performance. d) Correlation between performance improvement in UFOV (post – pre training) and improvement in TAPAT training task accuracy. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

D-KEFS verbal fluency category switching task (VFS)

A between-groups (TAPATSOP, ACSOP) univariate ANCOVA of post training VFS performance, controlling for pre training performance, revealed a significant between group difference (F (1,21) = 8.59, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.29) driven by greater performance in the TAPATSOP group (mean = 1.36, SD 0.96) relative to the AC group (mean = 0.61, SD 1.51) in number of accurate task related switches (i.e., spontaneous generation of unique words to semantic cues, alternating between two semantic categories). Improvement in the training task (i.e., target accuracy in the TAPAT task: session 21 – session 1) was correlated with improvements (post-pre) in verbal fluency switching (r = .61, n = 12, p = 0.03); see figure 5b. However, there was no relationship between amount of improvement at post training and level of performance before training.

D-KEFS Design fluency switch task (DFS)

A between-groups (TAPATSOP, ACSOP) univariate ANCOVA of post training DFS performance, controlling for pre training performance, revealed a significant between group difference (F (1,21) = 8.53, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.29) driven by greater performance in the TAPATSOP group (mean = 1.19, SD 1.02) relative to the AC group (mean = 0.72, SD 1.07) in number of accurate task related switches (i.e., spontaneous generation of unique designs, alternating between two visual cues). Specific improvements in the training task (e.g., change in target accuracy in the TAPAT task, session 21 – session 1) was not correlated with improvements (post-pre) in DFS (p > 0.05) and the amount of improvement in DFS that participants demonstrated at post training was not related to level of performance before training [p > 0.05].

Speed of Processing: UFOV

A between-groups (TAPATSOP, ACSOP) univariate ANCOVA of post training UFOV performance, controlling for pre training performance, revealed a significant between group difference (F (1,21) = 5.62, p < 0.03, partial η2 = 0.21) driven by greater performance in the TAPATSOP group (mean = 370.54ms, SD 156.44ms) relative to the AC group (mean = 482.00ms, SD 214.97ms). The amount of improvement in SOP that participants demonstrated at post training was highly correlated with level of performance before training [r = −0.70, n = 12, p = 0.01] indicating that participants with the slowest performance in the SOP showed the greatest improvements. Also, improvement in the training task (i.e., target accuracy in the TAPAT task: session 21 – session 1) was correlated with improvements (post-pre) in SOP (r = 0.65, n = 12, p = 0.02); see figure 5c. Given multiple significant correlations, we ran a linear regression predicting SOP improvement in which baseline SOP performance and TAPAT training improvement were entered simultaneously as predictors. The overall model was significant [F (2,9) = 10.15, p < 0.01) with an R2 of 0.69, and both baseline SOP performance and TAPAT training improvement significantly uniquely predicted SOP improvement.

5.1.4 Follow-up

To determine if the effects of TAPATSOP training versus ACSOP were maintained following the six-week no contact period at the end of training, we performed a repeated-measures MANOVA using the four outcome measures: spontaneous verbal and visuographic set shifting (D-KEFS verbal fluency switch task and design fluency switch task, respectively); Trails B; and the UFOV task. The four measures were included as dependent variables (Tests), and Time (post/follow-up) and Group (TAPATSOP, ACSOP) as factors. The MANOVA revealed only one significant main effect of test [F(3,20) = 37.83, p < 0.0001, Wilks’ λ = 0.15]. Both Test x Group [F(3,20) = 1.78, p = .183, Wilks’ λ = 0.79] and Test x Group x Time interactions [F(3,20) = 2.07, p = 0.136, Wilks’ λ = 0.76] were insignificant. This suggests that the training effects were no different at delayed follow up relative to post training in these outcome measures.

However, to assess the significance of each measure, we performed between-groups univariate ANCOVAs for each of the four measures, evaluating performance on each measure at follow-up while controlling for baseline performance (pre-training). We corrected for multiple comparisons using a false discovery rate of p = 0.0375, per Benjamini and Hochberg (1995). Results are presented by measure below.

Trails B

A between-groups (TAPATSOP, ACSOP) univariate ANCOVA of Trails B performance at follow-up, controlling for pre training performance, failed to reveal a significant between group difference (F (1,21) = 1.37, p = 0.25, partial η2 = 0.61). Performance in the TAPATSOP group (mean = 0.55, SD 0.85) relative to the AC group (mean = 0.35, SD 1.12) in time required to accurately switch between numbers and letters to complete the set.

D-KEFS verbal fluency switch task (VFS)

A between-groups (TAPATSOP, ACSOP) univariate ANCOVA of VFS performance at follow-up, controlling for pre training performance, revealed a significant between group difference (F (1,21) = 7.46, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.26) driven by greater performance in the TAPATSOP group (mean = 1.53, SD 0.83) relative to the AC group (mean = 0.66, SD 1.32) in number of accurate task related switches (i.e., spontaneous generation of unique words to semantic cues, alternating between two semantic categories).

D-KEFS Design fluency switch task (DFS)

A between-groups (TAPATSOP, ACSOP) univariate ANCOVA of DFS performance at follow-up, controlling for pre training performance, failed to reveal a significant between group difference (F (1,21) = 0.54, p = 0.47, partial η2 = 0.03). Performance in the TAPATSOP group (mean = 1.00, SD 0.91) relative to the AC group (mean = 1.16, SD 0.90) in number of accurate task related switches (i.e., spontaneous generation of unique designs, alternating between two visual cues).

Speed of Processing: UFOV

A between-groups (TAPATSOP, ACSOP) univariate ANCOVA of UFOV performance at follow-up, controlling for pre training performance, revealed a significant between group difference (F (1,21) = 4.96, p < 0.037, partial η2 = 0.19) driven by greater performance in the TAPATSOP group (mean = 402.18ms, SD 225.77ms) relative to the AC group (mean = 478.65ms, SD 204.85ms).

5.1.5 Exploratory Dose-Response Analysis

The design of experiment 1 did not include a delayed follow up assessment visit prohibiting analyses examining the durational aspects of TAPAT training. However, given the differences in training time (Exp 1 = ~5h vs. Exp 2 = 12h), we examined the influence of training duration on magnitude of initial training gains on Trails B, as it was employed in both experiments. Repeated measures ANOVA examining performance on Trails B with Time (pre, post) and Group (TAPAT intervention Exp 1, TAPAT intervention Exp 2) as factors revealed a significant main effect of Time [F(1,21) = 18.70, p < 0.0001], but not a Time x Group interaction [F(1,21) = 0.395, p = 0.536].

6. General Discussion

The benefits shown in older adults following alertness training in the current preliminary study are consistent with those reported in prior TAPAT studies in acquired brain injury (DeGutis & Van Vleet, 2010; Van Vleet et al., 2015; Van Vleet & DeGutis, 2013) and suggests that enhancing alertness can also benefit the more intact aging brain. In experiment 1 of the current study, compared to an active control training condition (AC), older participants that completed a computerized tonic and phasic alertness training program (TAPAT) showed improved intrinsic cognitive alertness which generalized to untrained cognitive domains including selective attention (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2005), working memory span and verbal fluency. In experiment 2, training to improve cognitive alertness was shown to improve performance in untrained, complex and effortful measures of executive function, particularly set shifting. This finding is consistent with a recent report involving patients with mild traumatic brain injury, in which TAPAT related improvements in cognitive alertness benefitted performance in standard measures of executive function (Van Vleet et al., 2015).

As shown previously, alertness influences the capacity to sustain attention, which is critical for effective executive function (Chan, 2002; Chan et al., 2003; Cicerone, 1996; Felmingham et al., 2004; Ponsford & Kinsella, 1992; Spikman & van der Naalt, 2010; Stuss et al., 1989; Stuss et al., 1989). In the current study, enhancement of alertness, as evidenced by improvement in target accuracy over the TAPAT training period suggested improvements in sustained attention (Cheyne et al., 2006; Christoff et al., 2009; Hester & Garavan, 2005; Manly et al., 1999; Robertson et al., 1996; Smallwood et al., 2004, 2008). In fact, the magnitude of improvement in the training task was highly correlated with magnitude of improvements in attention and executive functions (e.g., selective attention, fluency, set shifting and speed of processing), and benefits were greatest in those participants with worse performance at baseline. These results suggest that older adults may benefit from exercises that improve intrinsic alertness, particularly those most-vulnerable older adults. Effective self-regulation of alertness in this population is important, as a number of studies have demonstrated that maintaining alertness to support sustained attention is effortful (i.e., not automatic), variable and prone to decline (e.g., vigilance decrements) (Esterman et al., 2015, 2012; Warm, Parasuraman, & Matthews, 2008), and has been linked to impairments in attention and executive function (MacDonald et al., 2009; MacDonald et al., 2006; Sonuga-Barke & Castellanos, 2007; Stuss et al., 2003; West et al., 2002), real world accidents (Molloy & Parasuraman, 1996) and frailty progression (O’Halloran et al., 2013).

The results of experiment 2 also indicate that alertness training may improve new learning in older adults, as participants in the TAPAT versus the AC group demonstrated greater learning proficiency over time and achieved a higher level of performance overall in a speed of processing (SOP) challenge that was administered each session prior to training. Differences in the rate of SOP skill acquisition between groups were not apparent in the first half of training, suggesting that the effect was not driven by momentary boosts in alertness (see Van Vleet et al., 2011). Rather, differences in the rate of improvement were only evident after participants in the TAPAT group had accumulated ~5 hours of alertness training (latter half of training), consistent with prior TAPAT studies in which the effects of training were shown following a similar amount of time (DeGutis & Van Vleet, 2010; Van Vleet et al., 2015; Van Vleet & DeGutis, 2013). Alternatively, because the difficulty of the SOP challenge was greater in the second half of training, the influence of TAPAT may not have been evident in earlier, easy-to-moderate SOP difficulty levels. Notably, participants in the TAPAT group exhibited a negative slope in threshold scores over the last ten training sessions indicating that they required increasingly less time per trial in the latter half of training to perform at a high level of accuracy, despite increasing task difficulty. This finding suggests that participants in the TAPAT group may have continued to improve in SOP given more time on task, whereas participants in the AC group appeared to plateau in the second half of training (e.g., near zero slope over the last ten sessions). Finally, benefits in SOP following training generalized beyond the immediate training context, as participants in the TAPAT group showed greater gains in the Useful Field of View (UFOV) outcome measure (Ball & Owsley, 1993; Edwards et al., 2005), post versus pre training, compared to participants in the AC group. Collectively, improvements in SOP following TAPAT suggest that targeting alertness in cognitive training may reduce the time necessary to yield improvements in this task. This has important implications for real-world outcomes in older adults, as SOP has direct implications for driving safety (Ball et al., 2010; Edwards et al., 2009), functional efficiency, quality of life (Wolinsky et al., 2010) and protection from further cognitive decline (Wolinsky et al., 2013).

Benefits in speed of processing and executive function in experiment 2 were not restricted to the immediate post training period, as improvements in verbal fluency and speed of processing persisted following a six-week no contact period. This preliminary evidence suggests that an initial alertness training experience may produce lasting benefits, as shown in other cognitive training studies (Rebok et al., 2014). While additional, longer term follow up studies are required, the present results suggest that 12 hours of alertness training may represent an adequate initial dosage for older adults. Persistence of benefits in executive function and SOP following 12 hours of training suggest that prior TAPAT studies in patients with acquired brain injury, in which the initial dosage was ~5 hours, may have shown more persistent effects with a longer initial training period.

Given the persistent beneficial effects shown in the current study, it is possible that TAPAT improved alertness and executive functions in older adults in several ways. First, TAPAT may have bolstered underlying neural mechanisms of alertness by improving the actions of noradrenaline, which mediates enhancement of arousal (O’Connell et al., 2008) increasing the general level of neuronal excitability or baseline level of attention (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2005; Sara, 2009; Sara & Bouret, 2012). This, more optimal state of attention (see phasic mode, Aston-Jones & Cohen, 2005) may produce more general or indirect benefits, rather than direct performance improvements related to a specific declining neurological system (Craik, 1986; Craik & Byrd, 1982; see Zacks, Hasher, & Li, 2000). Indirect benefits of alertness training may act by bolstering cognitive reserve (Stern, 2009, 2012), which may be shown in processes that serve a non-task-specific function and allow one to maintain performance across a range of tasks (Robertson, 2013). Cognitive reserve processes affected by TAPAT could include arousal or alertness, response to novelty, sustained attention and self-monitoring/error awareness (Robertson, 2014). Related, alertness training may effectively improve cognition in older adults through enhancing compensatory scaffolding mechanisms (Park & Reuter-Lorenz, 2009); specifically, the recruitment of additional non-specific neural circuits to compensate for inefficiency or noise in task specific circuits. Cognitive training, sustained engagement in a novel task or environment, and exercise have all been shown to enhance the development of compensatory scaffolding (Park & Reuter-Lorenz, 2009; Voss et al., 2010; see also brain maintenance and cognitive lifestyle Nyberg et al., 2012; Valenzuela et al., 2011). Future studies that include a broader behavioral battery (e.g., measuring response to novelty, self-monitoring/error-awareness) and neuroimaging methods to evaluate brain changes after training would be useful to better understand TAPAT’s therapeutic effects.

In addition to improving alertness and executive functions, TAPAT also enhanced the rate of SOP skill acquisition in experiment 2. This effect could either be interpreted as having direct, indirect, or possibly synergistic effects. First, TAPAT has previously been shown to improve visuospatial attention in individuals with severe spatial deficits (DeGutis & Van Vleet, 2010; Van Vleet & DeGutis, 2013) and thus, may have directly improved visuospatial awareness (and performance) in the SOP challenge, as the task contains a divided spatial attention challenge. Alternatively, TAPAT may have promoted a more optimal attentional state (see Tang & Posner, 2009) that was conducive to learning a new task, indirectly improving SOP performance. A final possibility is that combining TAPAT and SOP exercises produced an effect that is greater than the sum of its constituent training approaches (i.e., synergistic effects). This has been shown when combining a pharmacotherapy with behavioral training (Berthier et al., 2009; Knecht et al., 2004), but not with two cognitive training approaches. For example, both memantine and speech therapy have been shown to improve dysphasia, but when combined produce even greater outcomes than their additive effects (Berthier et al., 2009). Future studies would be useful to determine if intelligently combining cognitive training approaches, or other validated forms of rehabilitation (e.g., alertness training and occupational therapy), can produce larger than additive effects.

The interpretation of present results must take into consideration the limitations of the study. For example, given the small sample size, the results are considered preliminary. Also, while participants in the TAPAT group demonstrated improvements in several measures of executive function relative to the AC group, a more comprehensive examination of executive functions post training is necessary to draw firm conclusions regarding the influence of alertness training in this domain. Also, while participants in the TAPAT showed greater learning proficiency (i.e., skill acquisition) relative to the AC group, it is unknown whether TAPAT would also influence other forms of learning (e.g., implicit or explicit learning) and whether the effects would be evident if learning measures were administered pre and post training only. Finally, as this was an initial efficacy study of TAPAT in older adults, it’s important that future studies include functional outcomes and neuroimaging measures to better identify the mechanisms of improvement and directly evaluate the impact of alertness enhancement in daily functioning.

The results from the present study, albeit preliminary, may have broad implications, as the ability to maintain an alert and sustained level of engagement is essential for effective higher-order cognitive operations (e.g., learning and memory, decision making) that are often in decline in older adults. In fact, failure to account for alertness may forestall meaningful gains in other forms of treatment. TAPAT represents a simple and highly scalable approach that exploits largely intact and arguably fundamental (Raz & Buhle, 2006) aspects of attention (e.g., alertness, vigilance) and the present results suggest that it may be effective in strengthening sustained attention, facilitating better executive functioning and more effecient learning.

Figure 2. Experiment 1: Correlations.

a) Correlation between improvement in second target accuracy (T2) in the attentional blink task (AB) (post – pre training), and baseline performance. b) Correlation between performance improvement in the controlled oral word association test (COWAT) (post – pre training) and improvement in TAPAT training task accuracy. c) Correlation between COWAT performance improvement (post – pre training), and baseline performance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by an award from the National Institute on Aging (NIA), R43 AG039965

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acevedo A, Loewenstein DA. Nonpharmacological cognitive interventions in aging and dementia. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2007;20(4):239–249. doi: 10.1177/0891988707308808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison P. Logistic Regression Using the SAS System. Second ed. SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, NC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Anand R, Chapman SB, Rackley A, Keebler M, Zientz J, Hart J. Gist reasoning training in cognitively normal seniors. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011;26(9):961–968. doi: 10.1002/gps.2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrés P, Parmentier FB, Escera C. The effect of age on involuntary capture of attention by irrelevant sounds: a test of the frontal hypothesis of aging. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44(12):2564–2568. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anguera JA, Boccanfuso J, Rintoul JL, Al-Hashimi O, Faraji F, Janowich J. Video game training enhances cognitive control in older adults. Nature. 2013;501(7465):97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature12486. others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JA, Labovitz SS. Effect of physical layout in performance of the Trail Making Test. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(2):220. [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. Adaptive gain and the role of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system in optimal performance. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2005;493(1):99–110. doi: 10.1002/cne.20723. http://doi.org/10.1002/cne.20723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Rajkowski J, Cohen J. Role of locus coeruleus in attention and behavioral flexibility. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46(9):1309–1320. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K, Berch DB, Helmers KF, Jobe JB, Leveck MD, Marsiske M. Effects of cognitive training interventions with older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2002;288(18):2271–2281. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.18.2271. others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K, Edwards JD, Ross LA. The impact of speed of processing training on cognitive and everyday functions. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62:19–31. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.special_issue_1.19. Spec No 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K, Edwards JD, Ross LA, McGwin G. Cognitive training decreases motor vehicle collision involvement of older drivers. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58(11):2107–2113. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03138.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball KK, Beard BL, Roenker DL, Miller RL, Griggs DS. Age and visual search: Expanding the useful field of view. JOSA A. 1988;5(12):2210–2219. doi: 10.1364/josaa.5.002210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K, Owsley C. The useful field of view test: a new technique for evaluating age-related declines in visual function. Journal of the American Optometric Association. 1993;64(1):71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Lindenberger U. Emergence of a powerful connection between sensory and cognitive functions across the adult life span: a new window to the study of cognitive aging? Psychology and Aging. 1997;12(1):12. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao S, Chan VT, Merzenich MM. Cortical remodelling induced by activity of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons. Nature. 2001;412(6842):79–83. doi: 10.1038/35083586. http://doi.org/10.1038/35083586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1995:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berthier ML, Green C, Lara JP, Higueras C, Barbancho MA, Dávila G, Pulvermüller F. Memantine and constraint-induced aphasia therapy in chronic poststroke aphasia. Annals of Neurology. 2009;65(5):577–585. doi: 10.1002/ana.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bherer L, Kramer AF, Peterson MS, Colcombe S, Erickson K, Becic E. Training effects on dual-task performance: are there age-related differences in plasticity of attentional control? Psychology and Aging. 2005;20(4):695. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bherer L, Kramer AF, Peterson MS, Colcombe S, Erickson K, Becic E. Transfer effects in task-set cost and dual-task cost after dual-task training in older and younger adults: further evidence for cognitive plasticity in attentional control in late adulthood. Experimental Aging Research. 2008;34(3):188–219. doi: 10.1080/03610730802070068. http://doi.org/10.1080/03610730802070068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdick DJ, Rosenblatt A, Samus QM, Steele C, Baker A, Harper M, Lyketsos CG. Predictors of functional impairment in residents of assisted-living facilities: The Maryland Assisted Living Study. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2005;60(2):258–264. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]