Abstract

Suturing is the standard of repair for lacerated flexor tendons. Past studies focused on delivering growth factors to the repair site by incorporating growth factors to nylon sutures which are commonly used in the repair procedure. However, conjugation of growth factors to nylon or other synthetic sutures is not straightforward. Collagen holds promise as a suture material by way of providing chemical sites for conjugation of growth factors. On the other hand, collagen also needs to be reconstituted as a mechanically robust thread that can be sutured. In this study, we reconstituted collagen solutions as suturable collagen threads by using linear electrochemical compaction. Prolonged release of PDGF-BB (Platelet derived growth factor-BB) was achieved by covalent bonding of heparin to the collagen sutures. Tensile mechanical tests of collagen sutures before and after chemical modification indicated that the strength of sutures following chemical conjugation stages was not compromised. Strength of lacerated tendons sutured with epitendinous collagen sutures (11.2 ± 0.7 N) converged to that of the standard nylon suture (14.9 ± 2.9 N). Heparin conjugation of collagen sutures didn’t affect viability and proliferation of tendon-derived cells and prolonged the PDGF-BB release up to 15 days. Proliferation of cells seeded on PDGF-BB incorporated collagen sutures was about 50% greater than those seeded on plain collagen sutures. Collagen that is released to the media by the cells increased by 120% under the effects of PDGF-BB and collagen production by cells was detectable by histology as of day 21. Addition of PDGF-BB to collagen sutures resulted in a moderate decline in the expression of the tendon-associated markers scleraxis, collagen I, tenomodulin, and COMP; however, expression levels were still greater than the cells seeded on collagen gel. The data indicate that the effects of PDGF-BB on tendon-derived cells mainly occur through increased cell proliferation and that longer term studies are needed to confirm associated genes.

Keywords: Aligned collagen suture, electrochemical compaction, Flexor tendon repair, Heparin, Growth factor delivery

1. Introduction

More than 30 million tendon and ligament injuries are reported globally every year [1]. The most common treatment of lacerated or ruptured tendons is suture based repair [1]. This treatment is generally attained by a mechanical load-bearing core suture. Epitendinous sutures are used to oppose damaged ends and to ease the gliding of the injured tendon. However, tendon is relatively poorly vascularized and its healing is a slow process which may result in fibrosis with inferior mechanics and function. Therefore, novel strategies are needed to accelerate tendon healing and to improve the quality of regeneration.

Growth factors are powerful regulators of biological function. The patterns of natural expression of platelet derived growth factor (PDGF-BB), basic fibroblast growth factor (β-FGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β1), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) vary dramatically over time during tendon healing [2]. According to recent studies, growth factor supplementation strategies have shown significant functional value in the context of tendon tissue regeneration [2-4]. Individually, PDGF-BB [3, 5] and IGF-1 [6] have been shown to alter proliferation, biological activities and collagen synthesis by tendon cells.

The recent past has seen the delivery of potent growth factors to the injury site to expedite tendon healing. Previous studies have applied growth factors to the injury site via local injection [7]. Although local injection is minimally-invasive, the short half-life of the growth factor (few minutes for PDGF-BB) [8] limits the therapeutic benefit. Several studies have exploited already existing sutures at repair site as vehicles for growth factor delivery [9-11]. Utilization of sutures may drive the repair to the inner continuum of the tendon stumps and expedite healing with increased repair strength. Past studies employed coating of standard synthetic polymeric sutures with growth factor doped gelatin or growth factor added scaffolds (generally fibrin) [12, 13]. These modifications are reported to achieve some success in the flexor tendon repair. Gelatin coating degrades fast and it is stripped while passing the suture. Fibrin scaffolds are weak and may be limited in terms of load bearing applications. Xenogeneic sutures are available on the market such as those prepared from the gut (Ethicon, Inc.) [14, 15]. Surgical gut suture may induce granuloma formation [16]. Other researchers developed and used syringe extruded collagen and fibrin threads for delivering stem cells to cardiac tissues [17, 18]. The bioactive suture concept needs to be improved to develop mechanically robust suture materials that can retain growth factors.

Collagen is conducive to cell adhesion, motility, proliferation and differentiation [19-24]. As importantly, collagen presents chemical sites for conjugation of growth factors. To the best of our knowledge, load-bearing growth factor conjugated pure collagen sutures have not been used for repair of lacerated tendons. Our group has developed electrochemical compaction and alignment of collagen molecules as a powerful method to obtain load-bearing collagen threads [25-28]. Such compaction and alignment has also been shown to induce tenogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells [25, 29]. Therefore, electrochemically aligned and compacted collagen (ELAC) holds promise as an epitendinous suture for repair of lacerated tendons. The aim of this study was to hybridize tenogenic potential of suturable ELAC threads with local growth factor delivery of PDGF-BB. This aim was achieved through conjugation of collagen sutures with heparin to attain the affinity bonding of the growth factor. The effects of the growth factor delivery on proliferation, metabolic activities, collagen production and expression of tendon-related genes by tendon-derived cells were investigated. We also demonstrate ELAC threads as functional epitendinous sutures and report the resultant biomechanical attachment strength in comparison to standard nylon sutures.

2. Materials and Methods

Overview of bioactive collagen suture preparation

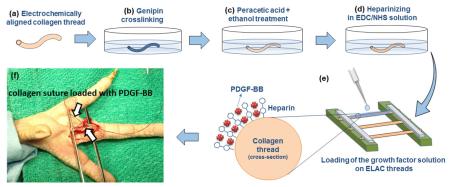

Schematic depiction of the preparation of affinity bound electrochemically aligned collagen suture is illustrated in Figure 1. Following the fabrication, ELAC sutures go through the stages of genipin crosslinking, peracetic acid ethanol treatment (Pet) and EDC/NHS conjugation of heparin before loading of the PDGF-BB.

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of the preparation of ELAC sutures with affinity bound PDGF-BB: (a) the principle of electrochemical process for preparing the aligned collagen threads as detailed in earlier publications [30, 44], (b) collagen threads go through three stages of chemical modifications of genipin crosslinking, Pet treatment, and heparin conjugation (c), PGDF-BB solution is added on heparinized threads and retained by affinity binding (d), actual image of collagen threads following aforementioned chemical processing steps (e).

Fabrication of aligned collagen sutures

Aligned collagen threads were fabricated using a custom-made automated device as we described previously [25]. Briefly, the device has two parallel electrode wires which are circumferentially wound around a rotating disc. Dialyzed collagen solution (Collagen Solutions Inc., bovine dermis, telocollagen, 3 mg/ml) is applied on the top of the rotating disc in between the two electrodes. Electrical current was applied at 10 A to the electrodes which results in the generation of a pH gradient between the electrodes. Collagen molecules in different pH solutions acquire different charges (negative near the cathode and vice versa for the anode) and the electrostatic repulsion of molecules by the electrodes push the collagen molecules toward the isoelectric point. Liquid collagen transforms into compacted threads in less than a minute following which the thread is collected onto a rotating spool. The collagen thread diameter was 0.11 ± 0.03 mm. The biophysical principles of collagen electrokinetics under pH gradients were modeled and discussed in detail in a prior study [30].

Genipin crosslinking

Genipin crosslinking enhances the strength of collagen threads to the level of the native tendon as we have demonstrated before [26]. Prior to genipin crosslinking, collagen suture was incubated in 1× PBS (Fisher scientific) for 6 h, and after that kept in isopropanol bath overnight. Following these steps aligned collagen sutures were crosslinked in genipin solution (0.625 g in 100 ml of 90% vol. ethanol solution) for 72 h [26]. Crosslinked aligned collagen sutures were washed thoroughly 3 times with deionized water, dried and kept at 4 °C.

Peracetic acid/ethanol treatment (Pet)

Genipin crosslinking limits the swelling ratio of collagen threads and usurps sites available for conjugation of heparin. This limitation was addressed by Pet process. Collagen sutures were incubated in peracetic acid solution for 4 h. Peracetic acid/ethanol solution consisted of 2% vol. Peracetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), 200 proof ethanol (Fisher Scientific) and deionized water (volume ratio 2/1/1) [31]. After 4 h the solution was removed and samples were rinsed thoroughly with deionized water 3 times for 15 mins each time. Samples were dried and stored at 4 °C.

Heparin conjugation to ELAC sutures

1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (life technologies) were used to crosslink heparin molecules to aligned collagen sutures. Sodium salt of heparin (extracted from porcine intestinal mucosa, Celsus, Inc.) was dissolved in EDC-NHS solution (EDC to NHS ratio of 0.72 and pH ≈ 7-8) at 3 different concentrations of 1 (low), 3 (medium), 10 mg/ml (high). Collagen sutures were soaked (10 cm of thread in each 2 ml of solution) in heparin-crosslinking solution for 2 h. After that collagen sutures were rinsed 3 times with deionized water for 15 mins each time, dried completely and stored at 4 °C. To find the amount of heparin which is crosslinked to collagen sutures, heparinized sutures were dissolved in 1 N HCl at 37 °C for 72 h. Dimethylmethylene Blue (DMMB) assay was used to measure the concentration of heparin in the solution which indicates the amount of heparin that is crosslinked to collagen sutures.

Mechanical Properties of peracetic acid treated and heparinized ELAC sutures

Sutures were tested in tension after genipin crosslinking, after Pet process and after heparinization (N= 8/group, sample length = 25 mm). Also, a group of suture which was genipin crosslinked, peracetic acid treated, and then crosslinked in EDC-NHS solution without heparin was tested to assess whether heparin contributes to mechanics of threads. Load-displacement curves were recorded using an ARES rheometer (TA instruments, New Castle, DA) as described previously [25]. Briefly, samples were soaked in 1× PBS for 24 h prior to testing. Samples were fixed onto the rheometer fixture with 10 mm gauge length and subjected to uniaxial tensile loading until failure at a strain rate of 10 mm/min. The load-displacement data were used to calculate the ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and Young’s modulus of collagen sutures. Mechanical properties of ELAC sutures were also measured after 3 weeks of cell culture (N= 8/group).

Mechanical properties of lacerated tendon sutured with ELAC in vitro

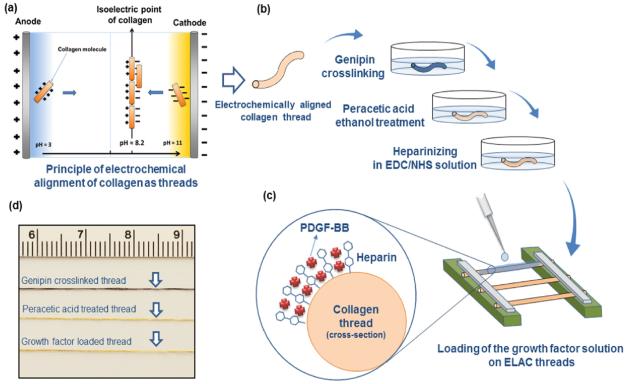

As the standard of care for flexor tendon repair, a non-absorbable braided or monofilament suture is usually used as the core suture. A secondary epitendinous suture is applied close to the laceration site [32]. In this study, ELAC was applied as the epitendinous suture to cadaveric tendons to assess whether it contributes to mechanical robustness of the baseline repair (Figure 3). The second digit flexor profundus tendon of chicken claw was cut with a scalpel. Two ends of the tendon were sutured together using a number 6-0 nylon core suture for load bearing purpose. Three groups were included. In the first group, only the nylon core suture was applied. In the second group, ELAC suture was used as epitendinous suture in addition to the nylon core suture. In the third group, a nylon suture was used as the epitendinous suture in addition to the nylon core suture. Sutured tendon samples were tested in tension (N= 3/group). Load-displacement curves were recorded using a materials test machine (Test Resources 800LE3-2, Test Resources Inc., MN, USA) as described previously [15]. Briefly, samples were kept hydrated via wet gauze with 1× PBS prior to testing for 24 h. Samples were fixed onto the fixture and subjected to uniaxial tensile loading until failure at a strain rate of 10 mm/min. The load-displacement data were collected and the load at failure is reported as a measure of the attachment strength attained by different suture types.

Figure 3.

Epitendinous ELAC suture contributed to mechanical stabilization significantly beyond that is provided by the core suture. (a) A comparison between 6-0 standard nylon suture and aligned collagen suture. (b) A lacerated flexor tendon of chicken is sutured with aligned collagen suture to demonstrate the feasibility of suturing. (c) Ultimate failure load of lacerated tendon with epitendinous collagen sutures is greater than that of the tendon repaired with only core nylon suture, and, significantly less than the tendon repaired by the epitendinous 6-0 nylon sutures. (d) Typical load-displacement curves of lacerated tendons sutured under different conditions (Scale bar: 10 mm).

Swelling ratio

Ten cm length of aligned collagen sutures from both untreated and peracetic treated group were weighed in the dry state. Samples were soaked in 1× PBS solution for 24 h to attain the equilibrium swelling state. Weights of samples were measured again and the following formula was used to calculate the swelling ratio of treated collagen suture:

Where the Ws is sample weight in the swollen state and Wd is sample weight in the dry state.

PDGF-BB release from heparinized collagen sutures

PDGF-BB release from collagen sutures was measured with and without heparin. Samples were prepared 3 cm in length and fixed horizontally on a jig and suspended in air (Figure 1d). Ten µl of PGDF-BB growth factor solution (containing 100 ng of the growth factor) was applied on samples with a micropipette. The solution was soaked and taken up completely by the originally dry sutures. Samples loaded as such were left to dry. Each sample was then placed in a low protein bind centrifuge tube and 2 ml of release media (0.1% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% NaN3 in 1× PBS) was added in each tube and incubated at 37 °C. At predetermined time points (2, 4, 6 h, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 15 days), the supernatant was removed and fresh release media was added. The cumulative amount of PDGF-BB in the release media from each sample was measured using a human PDGF-BB ELISA development kit (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) based on calibration curves derived using known concentrations of the growth factors (N=3 for each group per time points). The total PDGF-BB was determined to be the sum of the PDGF-BB in the release media and the remaining growth factor in the heparinized collagen sutures as determined by ELISA assay.

Isolation of Tendon-derived cells from Chicken Flexors

Chicken tendon tissue was dissected immediately post-mortem under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Case Western Reserve University (protocol No. 2013-0075). Chicken is a well-established model for studying flexor-tendon [1, 2] because it has a similar tendon anatomy to human hands and the prominences of flexor tendons facilitate the surgery [33, 34]. Cells were isolated from the second and the third digital flexor tendons of chickens (White leghorn chicken, aged 12 weeks and weighing approximately about 1-1.5 kg ) following published protocols [35]. Three cm of the tendon was dissected and minced in small pieces using a scalpel in a petri dish. Tendon pieces were washed thoroughly with 1× PBS and then digested in 0.25% collagenase II (Worthington, Freehold, N.J) in serum free Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (Gibco, Grand Island, N.Y) for 12 h at 37 °C. The tissue fragments were separated by low-speed centrifugation at 100 RPM for 1 min and the supernatant with cells was seeded on T-75 flasks for cells to adhere for 48 h. Cultures were rinsed with media, cells were trypsinized and seeded at a density of 350,000 in T-75 flask in growth media (low glucose Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium, 10% Fetal bovine serum, 1% peniciline/streptomycine, 1% l-glutamine, 50 µg ascorbic acid). Upon 90% confluence, cells were trypsinized with 0.25% trypsin and 0.1% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Gibco, Life technologies) and recultured at the same density. Cells were frozen at passage 2 and preserved in liquid nitrogen for later use.

Effect of heparinization on cell proliferation on ELAC sutures

Cells were seeded on 12 mm length suture samples as follows: 1) suture samples without heparinization, 2) low-level of heparin conjugation (1 mg/ml), and 3) high-level of heparin conjugation (10 mg/ml). Samples were sterilized in 70% v/v ethanol solution overnight and washed with 1× PBS 3 times each 15 mins. Ten pieces of 12 mm samples were placed in low attachment 24 well-plates. Tenocytes were seeded at a density of 20,000 per cm2 on samples in growth media (low glucose Dulbecco’s modified eagles medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% peniciline/streptomycine, 1% l-glutamine, 50 µg ascorbic acid). After 4 h, non-attached cells were collected by changing the media and counted to calculate the number of attached cells. After 7 days, Alexa fluor 488 (life technologies) for actin staining and DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining for cells nuclei were performed on samples. Cell numbers on samples were counted to calculate the proliferation of the cells on heparinized aligned collagen sutures. (N=3 per group).

Effect of PDGF-BB release from heparinized ELAC sutures on cell proliferation

Three groups were included: ELAC sutures samples, heparinized ELAC sutures samples with PDGF-BB (samples treated in 10 mg/ml heparin and the 100 ng PDGF-BB was loaded on each 3 cm of suture samples), and strips of uncompacted collagen gel were prepared as a reference point to tease out the effect of electrocompaction and alignment. Ten pieces of samples/group, each 30 mm in length, were soaked in serum supplemented media for 30 mins and placed in 6 well-plates as 10 samples per well. Cells were seeded as described earlier. After 4 h, non-attached cells were collected by changing the media and counted to calculate the number of attached cells to samples Alamar blue assay (life technologies) was performed on samples at day 7 to investigate the effect of PDGF-BB on metabolic activities of tendon-derived cells. Also, 3 samples per group were lysed and DNA quantification was performed to measure the cell proliferation at day 7 (N=3 per group, averages and standard deviations were reported).

Collagen solubilized to the media

Tendon derived cells were seeded on uncompacted collagen gel samples, ELAC sutures samples and ELAC sutures samples with PDGF-BB. Samples were cultured in ascorbic acid free media for 21 days. Every 3 days the media was collected and fresh media was replaced. All collected media for each group from different time points were mixed and total synthesized collagen by cells over 21 days was measured using the Sircol assay kit for measuring the amount of collagen in the culture medium (Sircol Soluble Collagen Assay, Biocolor Life Science Assays). A micro-plate reader (Spectramax M2, Molecular Devices) was used to measure the absorbance of the samples at 555 nm wavelength. Total collagen amount synthesized by cells were calculated by using the calibration curve plotted based on standard samples absorbance. Tests were repeated in triplets.

Histology

Tendon-derived cells were seeded on uncompacted collagen gel samples, ELAC sutures samples and ELAC sutures samples with PDGF-BB as described. Samples were cultured in the growth media supplemented with ascorbic acid for 21 days. Samples were fixed in 10% formalin solution at room temperature for histological processing. Fixed samples were placed through a series of increasing ethanol solutions and xylene steps to clear the constructs. Samples were then embedded in paraffin and cut into 5 µm sections. General histological staining of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson-trichrome were performed on xylene-cleared sections to highlight cell morphology and collagen production, respectively.

Effect of PDGF-BB release from heparinized ELAC sutures on tenogenic gene expression

The same three groups and seeding method were followed as described in the proliferation studies. At days 7, 14 and 21, the cells on samples were lysed using TRIzol Reagent (life technologies, NY, USA) and total RNA were extracted according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA (Applied Biosystems, CA, and USA). Taqman gene expression assays for scleraxis, type-I collagen, tenomodulin and COMP were used with the cDNA to evaluate the expression of genes using real-time PCR (Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System). The relative fold-change in target gene expression was quantified using the 2^(−δδCt) method (TaqMan Gene Expression Assays Protocol, Applied Biosystem, life technologies) by normalizing the target gene expression to RPLP-0 and relative to the expression on the random collagen at each time points. PCR experiments were run in triplicate at separate times (N=3).

Statistical analysis

Mechanical test data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s pairwise comparison to determine significant differences between genipin crosslinked sutures, peracetic treated sutures and heparinized sutures and also for significant differences in the failure loads between tendons sutured with only nylon core suture, core suture plus epitendinous ELAC suture and core nylon suture plus epitendinous nylon suture. Same analysis was used for cell proliferation, collagen production and gene expression data to find the significant differences in proliferation of cells on genipin crosslinked sutures, sutures with low (1 mg/ml) and high (10 mg/ml) concentrations of heparin. Data are reported as mean ± st. dev. Significance is reported at the level of p<0.05.

3. Results

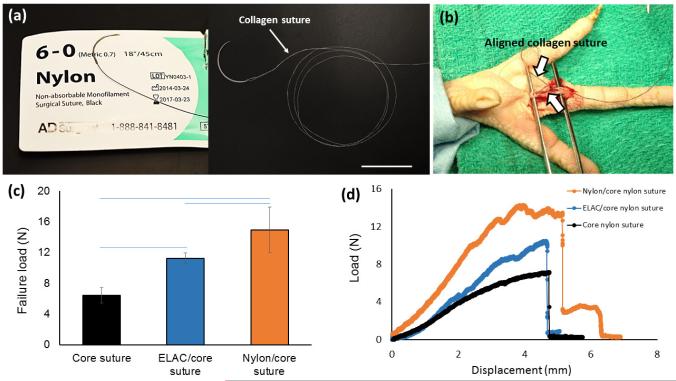

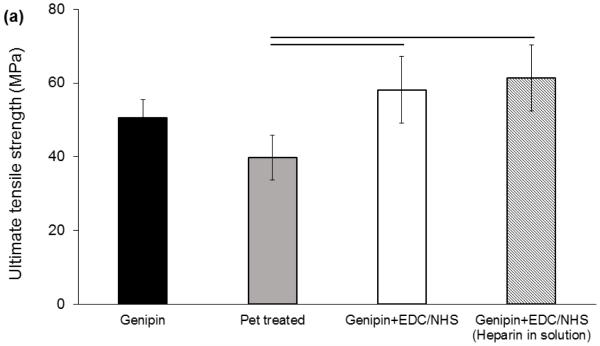

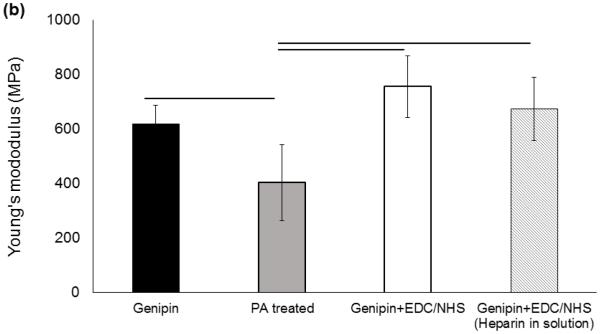

The preparation steps (Figure 1) influenced the mechanical properties of genipin crosslinked collagen sutures such that peracetic acid treatment reduced the tensile strength and modulus of collagen suture by 13% and 36%, respectively (Figure 2). However, this reduction was compensated by a 34% and 76% increase in strength and Young modulus of the peracetic acid treated collagen sutures, respectively, following the EDC/NHS heparin conjugation stage. Therefore, the final strength of sutures following heparin conjugation was not significantly different from the baseline genipin crosslinked sutures (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mechanical assessment of ELAC sutures during chemical modification stages. (a) Ultimate tensile strength of ELAC sutures declines following Pet treatment and increase after heparinization in EDC/NHS. Failure strength and Young’s modulus (b) of the sutures in the final state do not differ significantly from those of genipin crosslinked sutures. Presence of heparin in EDC-NHS solution doesn’t affect the crosslinking process of the collagen significantly. All significances reported at P<0.05.

Aligned collagen suture had similar dimensions with standard 6-0 nylon suture (Figure 3a). To illustrate the suturability of lacerated tendon with ELAC sutures and to demonstrate that the ELAC suture can augment the repaired tendon, a lacerated flexor tendon in chicken claw that was sutured with ELAC thread is illustrated as an example (Figure 3b). The core nylon suture alone provided a tensile failure load of 6.4 ± 0.9 N. Augmentation of core suture with ELAC or nylon epitendinous sutures improved the strength of the sutured tendon significantly by 75% and 130% (p<0.05), respectively (Figure 3c, d). Tendons sutured with ELAC epitendinous suture had significantly lower failure load (11.2 ± 0.7 N) than those sutured with 6-0 nylon epitendinous suture (14.9 ± 2.9 N).

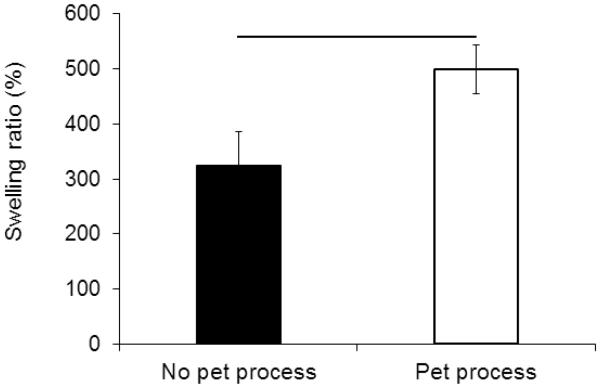

Following Pet process, the swelling ratio of collagen sutures increased by 54% from 324 wt.% to 498 wt.% (Figure 4). This process also bleached the dark blue color of the collagen sutures resulting from genipin crosslinking to a light brown tone (Figure 1d).

Figure 4.

Swelling ratio of the ELAC sutures showed 52% increase after Pet process from 325% to 498% (P<0.05).

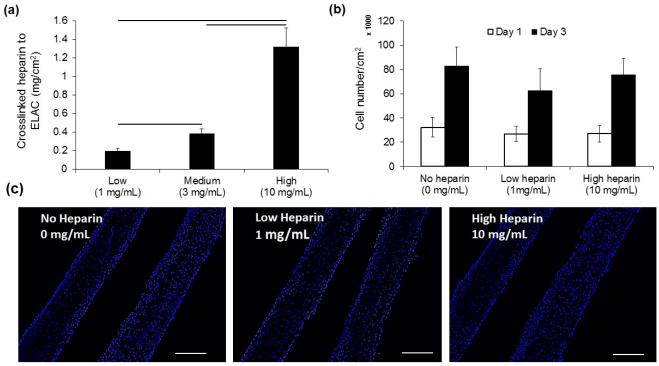

Increasing the concentration of heparin in the crosslinking solution from 1 mg/ml to 3 mg/ml and 10 mg/ml elevated the amounts of heparin which were crosslinked to collagen sutures from 0.19 ± 0.02 mg/cm2 to 0.38 ± 0.05 and 1.32 ± 0.2 mg/cm2 of collagen suture surface (Figure 5a). Results demonstrated that the cell proliferation on collagen sutures (Figure 5b) was not affected by the amount of conjugated heparin to collagen suture (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Heparin amount crosslinked to aligned collagen sutures does not affect proliferation of cells on sutures. The amount of heparin crosslinked to ELAC sutures can be controlled in a range from 0.19 ± .02 mg/cm2 of collagen to 1.32 ± 0.20 mg/cm2 by increasing the amount heparin from 1 mg/mL to 10 mg/mL in EDC-NHS solution (a). Quantification of the cell number (b) on samples with different amounts of heparin (c) and typical DAPI stained images of cell nuclei demonstrated that cell proliferation was not affected significantly by the amount of heparin crosslinked to ELAC sutures (P<0.05, Scale bar: 100 µm).

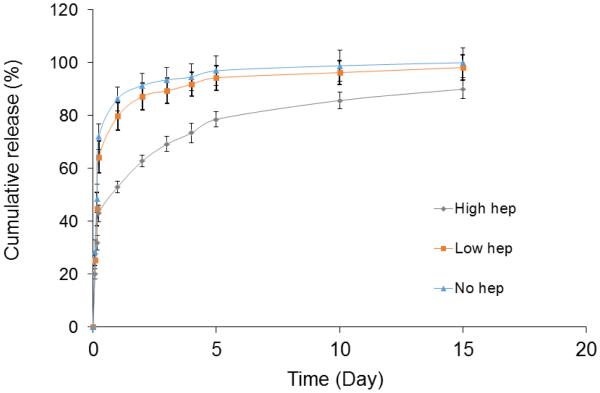

PDGF-BB release from 1 mg/ml heparin conjugation group was not different from that of the collagen sutures without heparin. ELAC sutures treated with high concentration heparin solution (10 mg/ml) attained a prolonged release over the 15 days period (Figure 6). PDGF-BB release by day 1 from collagen sutures without heparin and treated with low heparin were 86.3% and 79.6%, respectively. Collagen sutures treated with the highest concentration heparin released significantly less PDGF-BB at day 1 (52.9%). In the time span of day 2 to day 10, the collagen sutures conjugated with the highest amount of heparin solution released 32% of the growth factor and the sutures treated with low concentration of heparin solution released 16.6% of the total growth factor. For the rest of the results, only the sutures conjugated with the highest dose of heparin is reported.

Figure 6.

PDGF-BB release timeline was delayed with increasing amount of heparin conjugation from 0.19 ± 0.02 mg/cm2 to 1.32 ± 0.2 mg/cm2 of aligned collagen sutures.

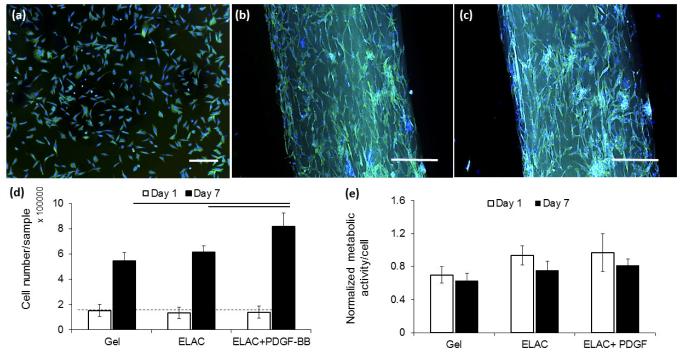

Fluorescent microscope imaging (Figure 7 a-c) of the cells seeded on sutures had elongated morphologies along the longer axis of the collagen suture. Delivery of PDGF-BB increased the proliferation of cells significantly (p < 0.05) and didn’t have A significant effect on cell metabolic activities in all of the three groups (Figure 7 d & e). DNA quantification showed the cell content on collagen sutures with PDGF-BB were 37% and 71% greater than that on collagen sutures without the growth factor and collagen gel samples, respectively.

Figure 7.

Cells morphologies visualized by Alexa-fluor staining of cellular actin filaments demonstrated round and isotropic morphologies with no directional elongation on collagen gel (a) compared to those on collagen suture without (b) and with (c) affinity bound PDGF-BB with higher unidirectional elongation and anisotropic morphologies. The results of DNA quantification (d) showed higher proliferation rate for cells on collagen suture with affinity bound PDGF-BB than cells on collagen suture without growth factor and collagen gel. Alamar blue assay showed similar metabolic activity with no significant difference for cells in all three groups at day 1 and 7 (e). (P<0.05, Scale bar: 50 µm).

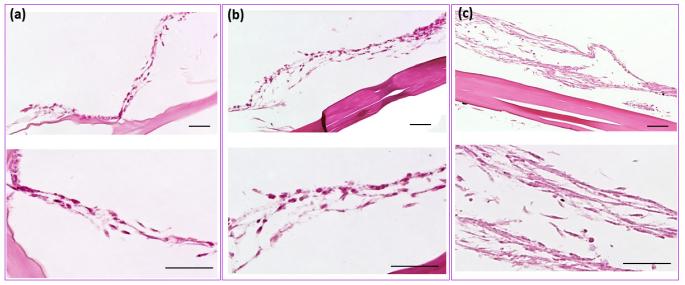

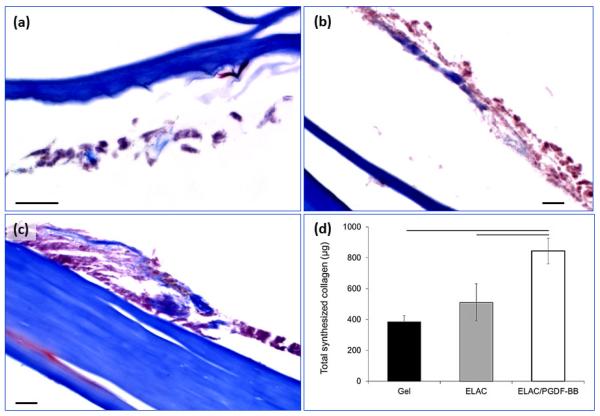

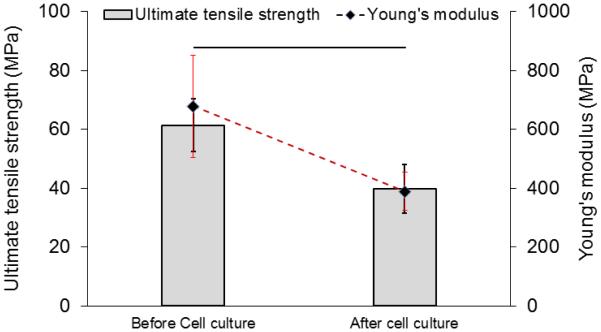

H&E staining (Figure 8a-c) of samples after 3 weeks of culture showed a significantly thicker layer of cells on the surface of the collagen suture with affinity bound PDGF-BB compared to sutures without PDGF-BB and collagen gel. Masson’s thrichrome stained sections demonstrated the presence of de novo collagen in the cells layers at day 21 time point (Figure 9a-c) with a more pronounced staining intensity for the growth factor treated group. Cell synthesized soluble collagen was quantified in the culture medium by sircol assay (Figure 9d). Amount of soluble collagen synthesized by cells on ELAC sutures conjugated PDGF-BB was 65% and 120% higher than ELAC sutures without growth factor and random collagen gel samples, respectively. Tensile strength and Young’s modulus of threads cultured with cells for 3 weeks showed a significant decrease (Figure 10) of 34% and 42%, respectively.

Figure 8.

H&E staining showed the cell layer on aligned collagen sutures with affinity bound PDGF-BB (c) and aligned collagen sutures without growth factor (b) and random collagen gel (a) after 3 weeks of cell culture. Higher magnification images of H&E stained samples showed the differences in cell layer thicknesses in all three groups. Cell layer thickness on collagen suture with affinity bound PDGF-BB is greater than cells on collagen suture without growth factor and also the collagen gel. (Scale bars: 50 µ m)

Figure 9.

Masson’s trichrome staining of samples from all three groups demonstrated that de novo collagen was present in all groups after three weeks of cell culture. The blue stain indicating the amount of deposited collagen by cells was more pronounced than other groups (a-c). d) This observation was in agreement with the quantification of collagen amount that is released to the culture medium by the sircol assay which demonstrated that the amount of cell synthesized soluble collagen was significantly higher on aligned collagen sutures with affinity bound PDGF-BB compared to aligned collagen sutures without growth factor and random collagen gel (d). (P<0.05, Scale bar: 20 µm)

Figure 10.

Results of tensile tests on collagen suture with affinity bound PDGF-BB showed that 3 weeks of cell culture reduces the tensile strength and Young’s modulus of the collagen suture significantly by 34% and 42%, respectively. (P<0.05)

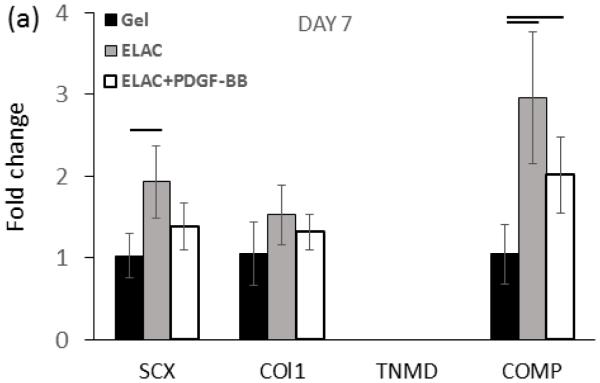

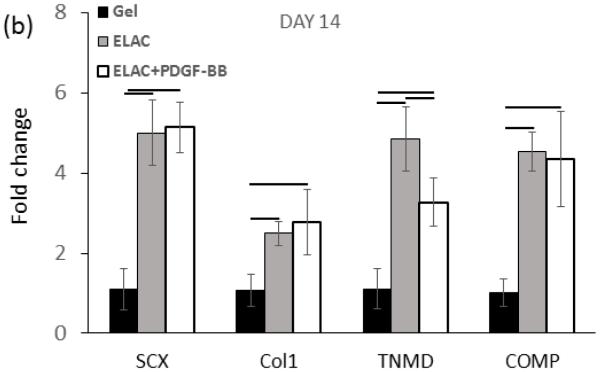

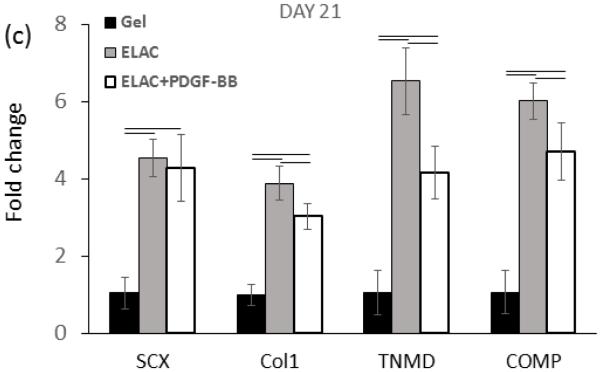

Real time-PCR analysis showed upregulation of Collagen I, SCX, COMP, and TNMD markers from day 7 up to day 21 on collagen suture both with and without affinity bound PDGF-BB (Figure 10a-c). However, upregulation of most of the markers were reduced moderately following the conjugation of PDGF-BB at day 21 of culture (p < 0.05). Tendon-specific marker of tenomodulin showed a late upregulation of 3.3 ± 0.6 and 4.1 ± 0.7 fold after 14 and 21 days on collagen sutures with PDGF-BB, and, 4.85 ± 0.80 and 6.54 ± 0.87 fold after 14 and 21 days on collagen sutures without PDGF-BB.

4. Discussion

Results of this study demonstrated that electrochemically aligned collagen sutures can be successfully functionalized with heparin to prolong PDGF-BB delivery. The conjugation process does not compromise the mechanical strength of threads. The net effect of PDGF-BB on cells was such that the metabolic activity, cell proliferation, and synthesized collagen by cells were significantly increased which is in agreement with previous works [3, 13]. On the other hand, delivery of PDGF-BB had a moderately deleterious effect on tenogenic expression such that markers were more strongly expressed on ELAC threads than threads loaded with PDGF-BB.

PDGF-BB has been reported to affect the differentiation of MSCs in various tendon regeneration applications. Cheng et al. [36] showed PDGF-BB released from PLGA particles improved adipose-derived MSC proliferation and upregulation of tendon-related markers like tenomodulin, scleraxis, tenascin C. Zhang and Wang [37] showed PDGF-BB to promote tenogenic differentiation of the tendon stem cells to active tenocytes. PDGF-BB was also used to enhance the tendon healing process via enhancing the cell proliferation and matrix production [3, 13]. Physical absorption of PDGF-BB by direct soaking of porous collagen scaffolds in growth factor laden solutions was used by Lynch et al. [38] for delivery of PDGF-BB. While this method is a simple single step process, release of growth factor occurs in hours. A fibrin/heparin scaffold delivery system was designed by Thomopoulos et al. [13] for delivery of PDGF-BB which attained sustained delivery profile over 10 days. This design was a non-load bearing sheet which is inserted with the tendon-proper. Placement of the sheet requires the creation of a gap invasively between the two ends of the tendon. Sutures provide a more practical and less invasive mean to deliver the growth factor. In this vein, Dines et al. [9] coated sutures with growth factor doped gelatin by simple dipping. While this method directly transferred the growth factor to place of injury, separation of the gelatin coating while threading the suture is a possibility. Furthermore, fast degradation of gelatin coating and lack of chemical bonding between growth factor and gelatin is likely to shorten the release profile timeline to less than a few days.

The delivery method we present has several key advantages. The first merit is the tenoinductive effect of aligned collagen threads by themselves. Our previous studies have shown such tenoinductive effect on human mesenchymal stem cells via the biomimetic topographical features presented by ELAC threads [25, 29]. Differently from these past studies, the current study demonstrated similar effects on tendon-derived cells from chickens, confirming the topographical tenoinductive effect of ELAC threads crosscuts across species and cell types. The tendon-derived cell population we employed in our study is bound to be heterogeneous with contributions from tenocytes, tenoblasts and MSCs. Therefore, the threads may not only serving a tenogenic differentiation in the context of MSCs, but also may help maintain the phenotype of harvested tenocytes and tenoblasts as demonstrated by upregulation of tendon-specific and tendon-related markers compared to random collagen gel which lacks alignment and compaction.

It is well known that PDGF-BB promotes proliferation of tendon derived cells as well as MSCs [2, 4, 36, 39, 40]. Pierce et al. [41] have shown the positive effect of PDGF-BB on matrix production through an increase in the TGFβ-1 expression; however, in vivo results by Hildebrand et al. [42] illustrated that there is no paired effect between PDGF-BB and TGFβ-1. Earlier studies demonstrated that single dose delivery of the growth factor does not affect the repair process because of the fast clearance of the growth factor from the injury site [8, 13, 43]. In this work, we demonstrated that heparinized collagen threads prolongs the delivery of PDGF-BB over the course of 15 days which resulted in a significant improvement in the proliferation of tendon derived cells. As the tendon fibroblast appear at the injury site by 2-5 days [13], a delivery time span of 10 days, which appears to be provided via our heparinized collagen thread, may improve the healing outcome in vivo.

Histology results confirmed that release of the PDGF-BB from the collagen suture enhances the cell proliferation (Figure 8a-c) notably as demonstrated by a thicker cell layer on collagen sutures with affinity bound PDGF-BB. The collagen production by cells as quantified by the amount of soluble collagen into the medium was the highest for the PDGF-BB treated group. In support of this result, cell deposited collagen in masson’s trichrome stained images was the most intense for the growth factor treated group. It is likely that the increased collagen amounts detected in the cell culture medium for PDGF-BB delivery group was the outcome of greater number of cells instead of greater degree of collagen production by each cell. Longer term cell culture studies, and more importantly animal models are needed to further confirm the usefulness of the heparinized collagen based growth factor delivery concept. Another aspect that remains to be investigated is whether PDGF-BB provides cues for recruitment and migration of fibroblasts.

Aligned collagen threads had sufficient mechanical robustness to be sutured in tendon indicating that the material is applicable surgically. While these collagen threads are exceptionally strong for a pure collagen biomaterial, they are not meant for suture based reinforcement. The primary purpose of collagen threads is drug delivery. Mechanical properties of collagen sutures were observed to decline by about 34% in the cell culture after 3 weeks, likely due to a combination of cellular and physical degradation. These results underlines that load bearing synthetic sutures are indispensable for providing baseline mechanical stability until the tissue heals. Whereas, the organic sutures can be implemented as biologic carriers for PDGF-BB to accelerate the healing of the tissues.

In this work, we demonstrated the upregulation of the tendon related markers (collagen I, tenomodulin, scleraxis, COMP) on aligned collagen thread with and without the PDGF-BB. However, in day 14 and 21 time points col I and tenomodulin gene expression were moderately lower for PDGF-BB including threads than threads absent with the PDGF-BB. In previous publications we showed electrochemically aligned collagen threads to guide MSCs toward tenogenic lineage via topographical cues and without administration of growth factors [25, 29]. Similar to the current study, previous work [29] from our group demonstrated that addition of BMP-12 (GDF-5) reduces the expression of scleraxis and tenomodulin moderately by day 14.

We have observed that despite the moderate reduction in tendon-specific and tendon-related gene expression of cells under a PDGF-BB regime, the amount of synthesized collagen in culture medium was enhanced. We believe that the reduction in the differentiation under PDGF-BB delivery is compensated by the beneficial effects of PDGF-BB on cell proliferation. Generally, it is well appreciated that proliferation and differentiation cues oppose each other and a successful repair outcome depends on balanced attainment of the both. While our results indicate the potential for enhancement in tendon repair via heparinized collagen threads, the formulation can be optimized further in terms of the level of heparinization and the amount of growth factor conjugated to collagen suture to achieve the best outcome in terms of cell proliferation and tenogenic markers expression. In doing so, delivery of PDGF-BB can be increased in the first week to increase cell number by proliferation. Therefore, prolonging the PDGF-delivery to longer time points may not be ideal by curbing the latent differentiation under the topographical tenogenic cues provided by aligned collagen fibers [25, 29].

Figure 11.

Real time-PCR results showed significantly higher upregulation of tendon-related markers of scleraxis, tenomodulin, collagen I, and COMP on ELAC threads with and without PDGF-BB. However, the PCR results of day 21 demonstrated that release of PDGF-BB form ELAC threads down-regulated tendon related markers’ expression moderately compared to collagen thread without PDGF-BB (d). (P<0.05)

Statement of significance.

A mechanically robust pure collagen suture was fabricated via linear electrocompaction and conjugated with heparin for prolonged delivery of PDFG-BB. Sustained delivery of the PDGF-BB improved the proliferation of tendon derived cells substantially at the expense of a moderate downregulation of tenogenic markers. The collagen threads were functionally applicable as epitendinous sutures when applied to chicken flexor tendons in vitro. Overall, electrocompacted collagen sutures holds potential to improve repair outcome in flexor tendon surgeries by improving cellularity and collagen production through delivery of the PDGF-BB. The bioinductive suture concept can be applied to deliver other growth factors for a wide-array of applications.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the AO Foundation Grant Number S-12-63K. Research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 AR063701. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kleinert HE, Kutz JE, Atasoy E, Stormo A. Primary repair of flexor tendons. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 1973;4:865–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molloy T, Wang Y, Murrell G. The roles of growth factors in tendon and ligament healing. Sports Med. 2003;33:381–94. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomopoulos S, Harwood FL, Silva MJ, Amiel D, Gelberman RH. Effect of several growth factors on canine flexor tendon fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis in vitro. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30:441–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa MA, Wu C, Pham BV, Chong AK, Pham HM, Chang J. Tissue engineering of flexor tendons: optimization of tenocyte proliferation using growth factor supplementation. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1937–43. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshikawa Y, Abrahamsson SO. Dose-related cellular effects of platelet-derived growth factor-BB differ in various types of rabbit tendons in vitro. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72:287–92. doi: 10.1080/00016470152846646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrahamsson SO, Lundborg G, Lohmander LS. Recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-I stimulates in vitro matrix synthesis and cell proliferation in rabbit flexor tendon. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:495–502. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang F, Liu H, Stile F, Lei MP, Pang Y, Oswald TM, et al. Effect of vascular endothelial growth factor on rat Achilles tendon healing. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2003;112:1613–9. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000086772.72535.A4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowen-Pope DF, Malpass TW, Foster DM, Ross R. Platelet-derived growth factor in vivo: levels, activity, and rate of clearance. Blood. 1984;64:458–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dines JS, Cross MB, Dines D, Pantazopoulos C, Kim HJ, Razzano P, et al. In vitro analysis of an rhGDF-5 suture coating process and the effects of rhGDF-5 on rat tendon fibroblasts. Growth Factors. 2011;29:1–7. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2010.526605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henn RF, Kuo CE, Kessler MW, Razzano P, Grande DP, Wolfe SW. Augmentation of Zone II Flexor Tendon Repair Using Growth Differentiation Factor 5 in a Rabbit Model. Journal of Hand Surgery-American Volume. 2010;35A:1825–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dines JS, Weber L, Razzano P, Prajapati R, Timmer M, Bowman S, et al. The effect of growth differentiation factor-5-coated sutures on tendon repair in a rat model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:S215–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomopoulos S, Kim HM, Das R, Silva MJ, Sakiyama-Elbert S, Amiel D, et al. The effects of exogenous basic fibroblast growth factor on intrasynovial flexor tendon healing in a canine model. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 92:2285–93. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomopoulos S, Zaegel M, Das R, Harwood FL, Silva MJ, Amiel D, et al. PDGF-BB released in tendon repair using a novel delivery system promotes cell proliferation and collagen remodeling. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:1358–68. doi: 10.1002/jor.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn DL. Ethicon wound closure manual. Ethicon, Inc; [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg JA, Clark RM. Advances in suture material for obstetric and gynecologic surgery. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2:146–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Truhlsen SM, Fitzpatrick J. The Extruded Collagen Suture: Tissue Reaction and Absorption. Arch Ophthalmol. 1965;74:371–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1965.00970040373017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guyette JP, Fakharzadeh M, Burford EJ, Tao ZW, Pins GD, Rolle MW, et al. A novel suture-based method for efficient transplantation of stem cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013;101:809–18. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Proulx MK, Carey SP, Ditroia LM, Jones CM, Fakharzadeh M, Guyette JP, et al. Fibrin microthreads support mesenchymal stem cell growth while maintaining differentiation potential. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011;96:301–12. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gey GO, Svotelis M, Foard M, Bang FB. Long-term growth of chicken fibroblasts on a collagen substrate. Exp Cell Res. 1974;84:63–71. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(74)90380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gospodarowicz D, Ill CR. Do plasma and serum have different abilities to promote cell growth? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:2726–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hauschka SD, Konigsberg IR. The influence of collagen on the development of muscle clones. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1966;55:119–26. doi: 10.1073/pnas.55.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosher RA, Church RL. Stimulation of in vitro somite chondrogenesis by procollagen and collagen. Nature. 1975;258:327–30. doi: 10.1038/258327a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lash JW, Vasan NS. Somite chondrogenesis in vitro. Stimulation by exogenous extracellular matrix components. Dev Biol. 1978;66:151–71. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier S, Hay ED. Control of corneal differentiation by extracellular materials. Collagen as a promoter and stabilizer of epithelial stroma production. Dev Biol. 1974;38:249–70. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(74)90005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Younesi M, Islam A, Kishore V, Anderson JM, Akkus O. Tenogenic Induction of Human MSCs by Anisotropically Aligned Collagen Biotextiles. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24:5762–70. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201400828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alfredo Uquillas J, Kishore V, Akkus O. Genipin crosslinking elevates the strength of electrochemically aligned collagen to the level of tendons. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2012;15:176–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Islam A, Chapin K, Younesi M, Akkus O. Computer aided biomanufacturing of mechanically robust pure collagen meshes with controlled macroporosity. Biofabrication. 2015;7:035005. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/7/3/035005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Younesi M, Islam A, Kishore V, Panit S, Akkus O. Fabrication of compositionally and topographically complex robust tissue forms by 3D-electrochemical compaction of collagen. Biofabrication. 2015;7:035001. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/7/3/035001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kishore V, Bullock W, Sun X, Van Dyke WS, Akkus O. Tenogenic differentiation of human MSCs induced by the topography of electrochemically aligned collagen threads. Biomaterials. 2012;33:2137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uquillas JA, Akkus O. Modeling the electromobility of type-I collagen molecules in the electrochemical fabrication of dense and aligned tissue constructs. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40:1641–53. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0528-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheffler SU, Scherler J, Pruss A, von Versen R, Weiler A. Biomechanical comparison of human bone-patellar tendon-bone grafts after sterilization with peracetic acid ethanol. Cell Tissue Bank. 2005;6:109–15. doi: 10.1007/s10561-004-6403-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clare Langley JH. Focus On Flexor Tendon Repair. Journal of Bone and joints Surgery. 2009:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hitchcock TF, Light TR, Bunch WH, Knight GW, Sartori MJ, Patwardhan AG, et al. The effect of immediate constrained digital motion on the strength of flexor tendon repairs in chickens. J Hand Surg Am. 1987;12:590–5. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(87)80213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feehan LM, Beauchene JG. Early tensile properties of healing chicken flexor tendons: early controlled passive motion versus postoperative immobilization. J Hand Surg Am. 1990;15:63–8. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(09)91107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao Y, Liu Y, Liu W, Shan Q, Buonocore SD, Cui L. Bridging tendon defects using autologous tenocyte engineered tendon in a hen model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:1280–9. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000025290.49889.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng X, Tsao C, Sylvia VL, Cornet D, Nicolella DP, Bredbenner TL, et al. Platelet-derived growth-factor-releasing aligned collagen-nanoparticle fibers promote the proliferation and tenogenic differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:1360–9. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Wang JH. Platelet-rich plasma releasate promotes differentiation of tendon stem cells into active tenocytes. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:2477–86. doi: 10.1177/0363546510376750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lynch SEW-LL, Kestler HK, Liu YC. Platelet-derived growth factor composition and methods for the treatment of tendon and ligament injuries. Biomimetic Therapeutics I. USA2010. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lepisto J, Laato M, Niinikoski J, Lundberg C, Gerdin B, Heldin CH. Effects of homodimeric isoforms of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF-AA and PDGF-BB) on wound healing in rat. J Surg Res. 1992;53:596–601. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(92)90260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wroblewski J, Edwall C. PDGF BB stimulates proliferation and differentiation in cultured chondrocytes from rat rib growth plate. Cell Biol Int Rep. 1992;16:133–44. doi: 10.1016/s0309-1651(06)80107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pierce GF, Mustoe TA, Lingelbach J, Masakowski VR, Griffin GL, Senior RM, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta enhance tissue repair activities by unique mechanisms. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:429–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hildebrand KA, Woo SL, Smith DW, Allen CR, Deie M, Taylor BJ, et al. The effects of platelet-derived growth factor-BB on healing of the rabbit medial collateral ligament. An in vivo study. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:549–54. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260041401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson SN, Talmadge JE. Sustained release of growth factors. In Vivo. 2002;16:535–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng X, Gurkan UA, Dehen CJ, Tate MP, Hillhouse HW, Simpson GJ, et al. An electrochemical fabrication process for the assembly of anisotropically oriented collagen bundles. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3278–88. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]