Abstract

The hematopoietic system undergoes many changes during aging; the causes and molecular mechanisms behind these changes are not well understood. Wang et al. have recently implicated a circadian rhythm gene, Per2, as playing a role in the DNA damage response and in the expression of lymphoid genes in aged hematopoietic stem cells.

The hematopoietic system is known to undergo several changes during aging, including loss of its ability to regenerate itself, as well as diminished immunocompetence and elevated disease incidence. Many of these changes have been attributed to the altered functional potential of aged hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs); previous studies have shown that accumulation of DNA damage, transcriptional changes, epigenetic modifications and altered lineage contribution could be contributing, in part, to this change in functional potential [1] [2].

HSCs are subject to multiple sources of DNA damage, many of which are intrinsic to the cell. One contributing factor to the accumulation of DNA damage during aging is the downregulation of the DNA damage response (DDR) and repair genes associated with the quiescent nature of HSCs. Upregulation of these genes occurs when HSCs leave their quiescent state and enter the cell cycle [3]. Quiescence also helps prevent replication-associated DNA damage. Indeed, replicative stress has been implicated as a ‘driver’ of aging in HSCs [4]. Given the importance of maintaining genomic integrity of the stem cell population, there may be additional mechanisms in place to mitigate DNA damage accumulation in HSCs, such as expression of telomerase (for maintenance of telomere length) [5], or other novel cell type-specific molecular pathways. One such mechanism used by HSCs is the process of differentiation by which damaged stem cells are removed from the self-renewing population in response to DNA damage accumulation [6]. Interestingly, this response appears to be more robust in the lymphoid-biased subset of HSCs (Ly-HSCs) [6], correlating well with the skewed composition of the aged HSC compartment, which shows a significant decrease in the frequency of Ly-HSCs [7]. This, together with the overall loss of immunocompetence in aged animals, supports the hypothesis that there might be differential regulation of lineage-biased HSC subpopulations.

Wang et al. further explore such differential regulation of murine HSC subsets, and find that expression of lymphoid genes in Ly-HSCs is controlled – at least partially – by Per2 (period circadian rhythm 2). Per2 is a transcription factor that binds E-boxes and is largely studied in the mammalian brain in the context of circadian rhythms. However, E-boxes have been demonstrated to play a critical role in lymphopoiesis [8], and using an in vivo RNAi screen, the authors initially identified Per2 as a gene regulating HSC potential in the context of critically short telomeres. Downregulation of Per2 by shRNA significantly improved the functional potential of third generation (G3) telomerase-deficient mTerc−/− mouse stem cells and progenitors (Lin−, Sca-1+, c-Kit+, or LSKs) which have critically short telomeres. Loss of Per2 allowed these cells to robustly, and serially, reconstitute lethally irradiated recipients. The authors assayed the role of Per2 in damaged HSCs (irradiated, replication stressed, or purified from physiologically aged animals) and showed that regardless of how the damage was introduced, Per2−/− HSCs exhibited significantly improved function (including reconstitution capacity).

Given the increased functional potential of damaged Per2−/− HSCs, the authors examined the DDR of Per2 knockout (KO) cells. Although the number of γH2AX and 53BP1 foci (markers of DNA damage) were not affected by Per2 status in either young or aged HSCs, they observed a significant reduction of p-RPA (marker of replicative stress signaling) in Per2−/− HSCs that had undergone enforced replicative stress (serial transplant or hydroxyurea treatment). Hence, these data suggest that Per2 plays an important role in replicative stress signaling and furthermore, that the diminution of this signal may lead to the improved function of damaged HSCs. In addition to Per2’s role in replicative stress, the authors explored the DDR following gamma irradiation (IR). Upon IR, lineage negative (Lin−) Per2−/− cells exhibited a diminished ATM kinase response that led to reduced p-CHK1, p-CHK2 and p-p53 relative to wild type cells. The loss of PER2 protein was also associated with loss of BCL2 downregulation, BAX and PUMA upregulation as well as CASP3 cleavage. Accordingly, Per2 deletion also led to diminished survival of LSK cells whereas Per2 overexpression resulted in increased apoptosis of Lin− cells. Of note, IR induced the expression and stabilization of Per2 mRNA and protein in Lin− cells in a p53-independent manner, as Lin− p53−/− mouse cells also presented Per2 upregulation. Consistent with these findings, while p53−/− animals succumbed to tumors, Per2−/− mice did not. The authors then observed that IR-induced BATF – a regulator of AP1 previously shown to regulate HSC differentiation upon DNA damage [6] – was intact in Per2−/− HSCs, thus suggesting a potential mechanism by which Per2−/− mice might stay tumor-free.

In addition to its role in DNA damage signaling and survival, the authors also showed that Per2 plays a role in lineage potential. Interestingly, aged HSCs exhibited increased levels of Per2 mRNA and protein compared to young HSCs, though aged Ly-HSCs showed a more robust increase than My-HSCs. Moreover, deletion of Per2 rescued the diminished lymphoid potential of aged HSCs in a cell-intrinsic manner, as demonstrated in transplantation experiments. To mechanistically explain the rescue of lymphopoietic potential in Per2−/− HSCs, the authors analyzed the expression of lymphopoiesis-associated genes in young and aged wild type and KO Ly-HSCs. They observed increased expression of 23 of 71 lymphoid genes tested in Per2−/− HSCs, while the age-associated decrease in the expression of many of these genes was not observed in aged Per2−/− HSCs. To further explore the effect of Per2 on lymphoid potential, early B lymphocytic progenitors (EPBs) from Per2 KOs were examined. From a functional standpoint, not only did loss of Per2 lead to increased numbers of EPBs in the aged bone marrow, aged EPBs generated more mature B-cells upon IL7 stimulation in culture. Moreover, Per2 deletion also rescued the levels of blood IgG1 in aged mice, concomitant with a better immune response against Staphylococcus aureus infection.

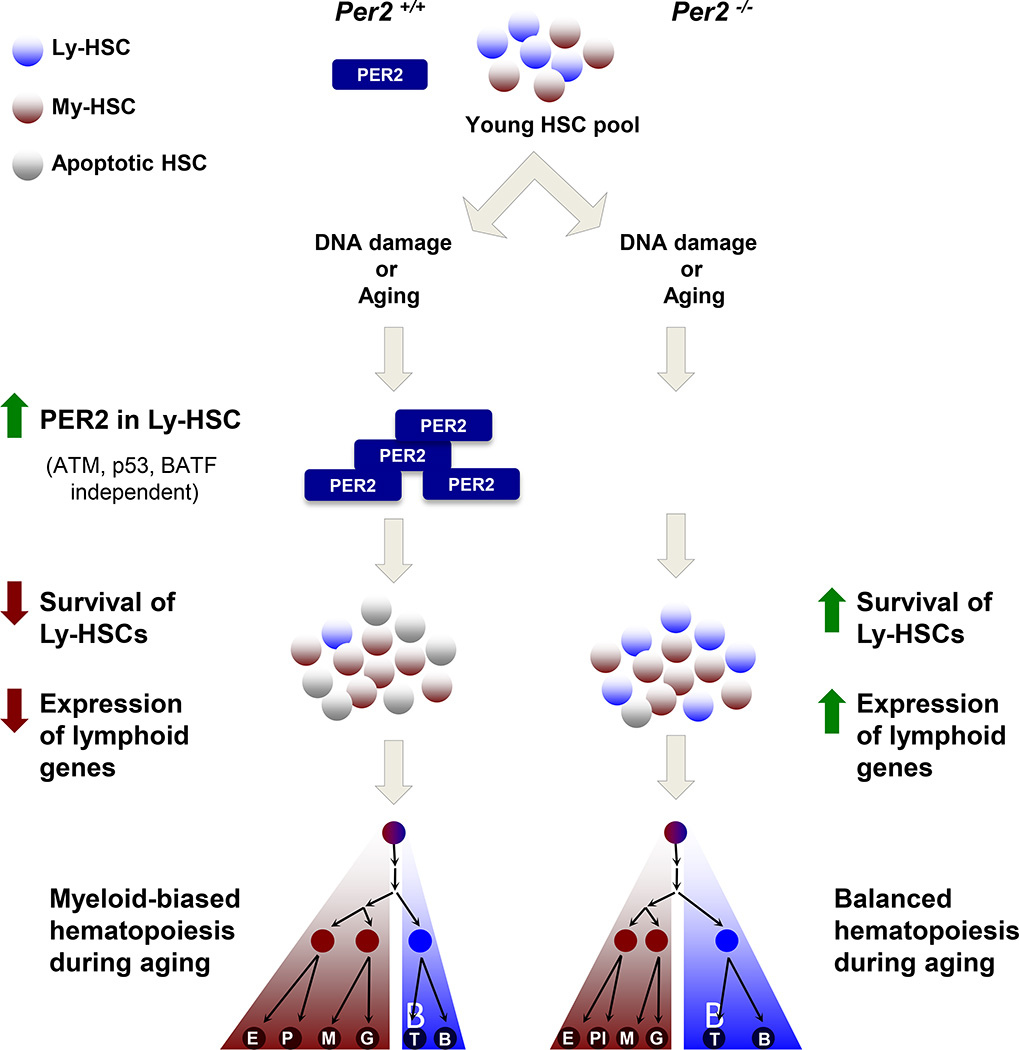

In summary, the study by Rudolph’s group demonstrates that following DNA damage or during aging, Per2 differentially regulates Ly-HSCs and ultimately, lymphopoiesis (Figure 1). These findings open the door to new questions, including elucidating how Per2 modulates the DDR in the HSC compartment and how it regulates the expression of lymphoid genes. Regarding the role of Per2 in DDR and survival, it will be interesting to see if Per2−/− HSCs display dampened replicative stress signaling or reduced sensitivity to stress (due to reduced overall cycling) compared to Per2+/+ HSCs. The authors report a more robust IR-induced Per2 expression upon IR or during aging in Ly-HSCs than in My-HSCs, but the analysis of downstream signaling following IR was studied only in Lin− cells, due to technical limitations of obtaining sufficient cell numbers. Consequently, given the heterogeneity of the Lin− population, the role of Per2 in response to IR in primitive cells may be obscured by the response of abundant, highly replicative lineage-committed progenitor cells.

Figure 1. Per2 Regulates DNA Damage Responses and Lymphoid Gene Expression during Aging or upon DNA Damage Induction.

In wild type HSCs, DNA damage or aging induces the upregulation of Per2 gene expression, and this response is more robust in lymphoid (Ly)-HSCs than in myeloid (My)-HSCs. Per2 deficiency (Per2−/−) in HSCs leads to a reduction both in cell survival and lymphoid gene expression, contributing to a myeloid-biased lineage output in aged animals. Per2 deletion also results in impaired loss of HSCs upon DNA damage, contributing to the maintenance of lymphoid gene transcription in Ly-HSCs, and leading to a more balanced lineage output during aging. E, erythrocyte; Pl, platelet; M, monocyte; G, granulocyte; T, T lymphocyte; B, B lymphocyte.p

PER2’s role in the regulation of lymphoid gene expression might be quite straightforward as it is a transcription factor that binds E-boxes, implicated in the modulation of genes important for lymphopoiesis [8]. Furthermore, in the brain, PER2 is associated with complexes that include the H3K9 histone methyltransferase HP1γ-Suv39h or the H3K9 histone deacetylase HDAC1 [9], chromatin marks typically associated with transcriptional repression. Given that epigenetic regulation has been previously shown to play an important role in stem cell aging [10], a putative loss of transcriptional repression stemming from PER2 deficiency might help explain, at least in part, how Per2−/− HSCs retain the expression of genes important for the lymphoid lineage during aging. However, this mechanism has not been formally examined in HSCs.

Ultimately, this study has defined a novel role for a circadian rhythm gene, Per2, as a regulator of HSC survival and lineage potential, possibly providing a therapeutic target to restore lymphoid potential in an aged HSC compartment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (K01AG050813-01A1 to I.B., R01HL107630 to D.J.R., U01HL107440 to D.J.R., U01HL099997 to D.J.R., 1UC4DK104218 to D.J.R., U19HL129903 to D.J.R.), the Jane Brock-Wilson Fund (to D.J.R), Google, Inc. (to D.J.R.), the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust (to D.J.R.), the New York Stem Cell Foundation (to D.J.R.), the American Federation for Aging (to D.J.R.) and the Boston Children’s Hospital Technology & Innovation Development Office (to D.J.R.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Geiger H, et al. The ageing haematopoietic stem cell compartment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:376–389. doi: 10.1038/nri3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossi DJ, et al. Stems cells and the pathways to aging and cancer. Cell. 2008;132:681–696. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beerman I, et al. Quiescent Hematopoietic Stem Cells Accumulate DNA Damage during Aging that Is Repaired upon Entry into Cell Cycle. Cell Stem Cell. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flach J, et al. Replication stress is a potent driver of functional decline in ageing haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2014;512:198–202. doi: 10.1038/nature13619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrison SJ, et al. Telomerase activity in hematopoietic cells is associated with self-renewal potential. Immunity. 1996;5:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J, et al. A differentiation checkpoint limits hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal in response to DNA damage. Cell. 2012;148:1001–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beerman I, et al. Functionally distinct hematopoietic stem cells modulate hematopoietic lineage potential during aging by a mechanism of clonal expansion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:5465–5470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000834107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ephrussi A, et al. B lineage-specific interactions of an immunoglobulin enhancer with cellular factors in vivo. Science. 1985;227:134–140. doi: 10.1126/science.3917574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duong HA, Weitz CJ. Temporal orchestration of repressive chromatin modifiers by circadian clock Period complexes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:126–132. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beerman I, Rossi DJ. Epigenetic Control of Stem Cell Potential during Homeostasis, Aging, and Disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:613–625. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]