Abstract

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disorder with large annual costs. This study evaluated utilization and costs for the management of MS relapses with H.P. Acthar® Gel (repository corticotropin injection; Acthar; Mallinckrodt) compared to receipt of plasmapheresis (PMP) or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) among patients with MS who experienced multiple relapses.

Methods

We identified patients with MS diagnoses who had relapses treated with intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP), the first-line treatment for MS relapse. Patients who were treated for the subsequent relapses were eligible for the study. We analyzed 12- and 24-month healthcare utilization and costs among patients who received Acthar prescriptions compared to patients who were treated with PMP/IVIG using generalized linear and logistic regression models to calculate unadjusted and adjusted means and 95% confidence intervals.

Results

For the 12-month analysis, a total of 213 patients received Acthar prescriptions and 226 were treated with PMP or IVIG. Patients who received Acthar prescriptions were similar to those who received other treatments in terms of most demographic variables. Acthar recipients had fewer hospitalizations (0.2 vs. 0.4; P = 0.01) and received fewer outpatient services (29 vs. 43; P < 0.0001) but received more prescription medications (36 vs. 30; P < 0.0001) compared to recipients of PMP/IVIG. Patients who received Acthar prescriptions had lower inpatient and outpatient costs ($15,000 lower; P = 0.001; and $54,000 lower; P < 0.0001, respectively) but similar total costs. Similar results were seen in the cohort with 24 months of outcome data.

Conclusion

Acthar may be a useful treatment option compared to PMP/IVIG for patients with MS experiencing multiple relapses.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant to the University of Washington from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-016-0363-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Costs, H.P. Acthar® gel (repository corticotropin injection), Healthcare resource utilization, Intravenous immunoglobulin, Multiple sclerosis, Neurology, Plasmapheresis

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disorder in which cells of the brain and spinal cord are damaged, causing a wide range of neurological symptoms. The most common symptoms of MS exacerbations include paresthesia, motor symptoms, such as muscle cramping or spasticity, spinal cord symptoms, such as bladder, bowel, or sexual dysfunction, and fatigue [1]. As of 2013, more than 2.3 million people worldwide had been diagnosed with MS [2]. On average, annual direct healthcare costs for patients with MS have been shown to be about $24,000 higher compared to the non-MS population [3]. Along with disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), which are designed to reduce inflammation and the risk of subsequent relapses [4, 5], one of the major drivers of the increased costs in the MS population is expenses related to treating MS exacerbations (relapses) [3]. Medicare data showed that direct costs in patients who experienced relapses were around $17,000 per year, while the costs during remission were about $7300 per year and costs during periods of stabilization were around $4000 per year [3]. In addition, the expense of treating relapses increases with severity [6]. Compared to a cohort of patients with MS who did not experience any relapses, those who experienced low/moderate severity relapses and high severity relapses had $8269 and $24,180 higher annual incremental direct costs, respectively [6]. Furthermore, MS diagnoses and relapses are associated with significantly reduced health-related quality of life [7, 8], with patients with MS having about ten fewer quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) compared to patients without MS [9].

MS relapses are usually treated with short courses of high-dose corticosteroids, including intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP) or high-dose oral prednisone (Deltasone®; Pfizer). However, around 20% of patients with MS who initiate treatment with high-dose corticosteroids change to other therapies within several months, likely due to poor response [10, 11] or patient preferences [12]. Alternative therapies include intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), which reduces or prevents activation of inflammatory cells and alters antibody responses [13], plasmapheresis (PMP), which may remove circulating antibodies from blood that cause MS symptoms [14], and H.P. Acthar® Gel (repository corticotropin injection; Acthar; Mallinckrodt), which is thought to have anti-inflammatory properties and works through multiple mechanisms that include indirectly increasing corticosteroid production [15]. Because few studies have focused on patients who received therapies besides IVMP, the purpose of this paper was to describe and generate hypotheses regarding health utilization, outcomes, and costs resulting from the management of MS relapses with Acthar compared to PMP or IVIG among patients with MS who experienced multiple relapses.

Methods

Study Population and Data Source

We used the Truven Health Analytics MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases to identify a population of patients with MS. These databases contained inpatient, outpatient, pharmacy claims, and insurance coverage data for patients covered by commercial insurance plans across the US. The inpatient and outpatient claims databases included procedure and visit level details from medical claims, such as the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, dates of service, and variables describing financial expenditures. The pharmacy claims database provided details, including National Drug Codes (NDC), dates dispensed, quantity and days’ supply, and payments. Separate eligibility and demographics file provided additional information about subjects, such as age, gender, insurance plan type, geographic location, and enrollment status by month.

Because we were interested in evaluating treatments for MS relapses, we limited our study to patients in the database who experienced at least two MS exacerbations between July 1, 2007 to December 31, 2012 for the 12-month analyses or through December 31, 2011 for the 24-month analyses. Patients in both the 12- and 24-month analyses were followed for outcomes until December 31, 2013. We initially identified eligible patients with MS diagnoses (ICD-9-CM code 340.X) who had relapses that were treated with IVMP, the first-line treatment for MS relapse. Patients who were treated for the subsequent relapses were eligible for the study. The index date was the calendar date in which we observed a subsequent treated relapse at least 30 days after the initial relapse with the primary ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for MS along with a claim for one of the non-IVMP relapse treatments: Acthar, IVIG, or PMP (Table 1). We excluded patients who were not enrolled in their health plans continuously for 6 months prior to and for 12 (for the 12-month analyses) or 24 (for the 24-month analyses) months after the index dates.

Table 1.

Codes for treatment of multiple sclerosis relapses

| Treatment name | NDC, CPT, or HCPCS code |

|---|---|

| H.P. Acthar Gel (repository corticotropin injection; Acthar) | NDC = 63004-77310-1, 63004-8710-01; HCPCS = J0800 |

| IVMP | HCPCS = J2920, J2930 |

| IVIG |

CPT = 90284, 90283 HCPCS = J1559, J1561, J1562, J1566, J1568, J1569, J1572, J1599 |

| PMP | CPT = 36514, 36515 |

CPT Current Procedural Terminology, HCPCS Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System, IVIG intravenous immunoglobulin, IVMP intravenous methylprednisolone, NDC National Drug Code, PMP plasmapheresis

Statistical Analysis

We examined associations between receipt of prescriptions for Acthar versus treatment with PMP/IVIG and 1) 12-month cost and utilization outcomes and 2) 24-month cost and utilization outcomes. We initially intended to examine only 24-month costs and utilization but examined 12-month outcomes after discovering that relatively few patients met our exclusion criteria for 24-month outcomes. By definition, all the subjects in the 24-month analyses were also included in the 12-month analyses. We combined patients who received PMP with patients who received IVIG because of small numbers in each individual treatment group and because these are the next line of therapies used after corticosteroids [16, 17]. Patients who received Acthar prescriptions more than 30 days after their subsequent exacerbation (index date) were excluded from these analyses, but patients in the Acthar group may have received other treatments (IVMP, IVIG, or PMP) in addition to their Acthar prescriptions within 30 days of the index exacerbation. We examined proportions and Chi-square tests (for categorical variables) and means, standard deviations, and t tests (for continuous variables) of factors that might have been related to health costs and outcomes and receipt of Acthar prescriptions, including patient age, gender, type of health insurance plan, Deyo–Charlson Comorbidity Index [18, 19], comorbidity categories, geographic region, year of index relapse, and the number of outpatient services, hospitalizations, and medications filled in the 6 months prior to index incident. Variables with P values of <0.05 were considered significant confounders in the subsequent adjusted regressions. The authors were not blinded to whether subjects received Acthar or PMP/IVIG when we performed the analyses.

Next, we calculated unadjusted means, medians, ranges, and standard deviations of each healthcare utilization and cost among patients who received Acthar prescriptions compared to patients who received treatment with PMP or IVIG. We calculated the proportions of costs contributed by inpatient stays, outpatient services, and medications. We also calculated the absolute differences and the p values for the differences between these means for patients who received Acthar prescriptions versus patients who received treatment with PMP or IVIG. Outcomes related to hospitalizations (length of stay, ICU admissions, and readmissions) were only calculated among patients with MS with at least one hospitalization. Similarly, MS-related emergency department visits were only evaluated among patients with at least one emergency department visit. If the index MS exacerbation was identified from a hospitalization to receive treatment with IVIG or PMP, then that index inpatient stay was not counted as a subsequent utilization. Rehabilitation and long-term care services were defined as inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing facilities, inpatient long-term care, nursing facilities, and custodial care facilities. We then performed generalized linear regressions for each of the outcomes, adjusting for patient variables that were significantly associated with receipt of Acthar prescriptions. For outcomes with count variables, such as the number of hospitalizations, length of hospital stay, number of admissions to an intensive care unit (ICU), number of emergency department visits, number of MS-related emergency department visits, number of outpatient services, number of rehabilitation services, the number of prescription medications filled, and number of all healthcare services combined we used generalized linear regression with a log link and specified the Poisson distribution to calculate adjusted means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For the binary outcome of whether patients were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of discharge, we used logistic regression to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. For total costs, we used generalized linear regression with a log link and specified the gamma distribution to calculate adjusted means and 95% CIs. We also calculated the absolute differences between the adjusted means, as well as the 95% CI of these differences.

SAS for Windows, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analyses.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, revised in 2013. This study was exempt from review by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (IRB) through self-determination.

Results

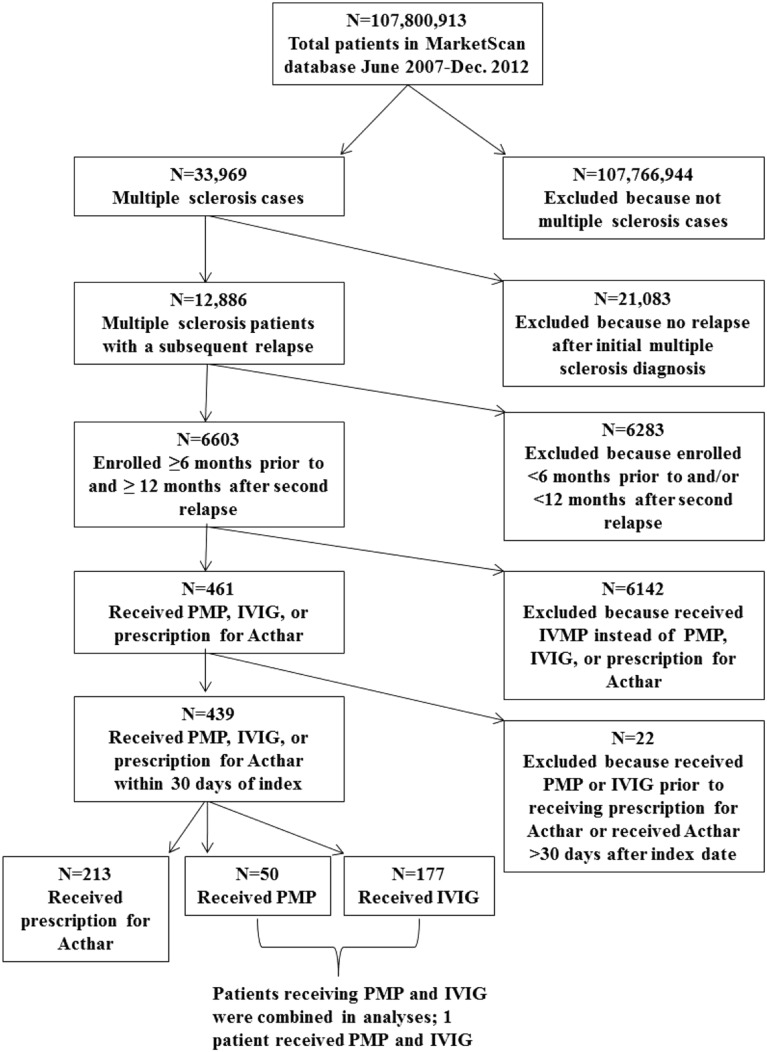

For the 12-month analysis, a total of 6603 patients who met our enrollment criteria experienced second relapses; of these, 461 (7%) received PMP, IVIG, or prescriptions for Acthar. A total of 213 unique patients received Acthar prescriptions within 30 days of the index date, and 226 were treated with PMP or IVIG; 1 patient received both PMP and IVIG (Fig. 1). Six patients who received Acthar prescriptions were excluded, because they received treatment with PMP or IVIG prior to receiving Acthar prescriptions and 16 patients who received Acthar prescriptions more than 30 days after index exacerbation were deleted from these analyses. In the 24-month analysis, 3836 patients who met our enrollment criteria experienced second relapses and 238 (6%) of these received PMP, IVIG, or prescriptions for Acthar. A total of 96 patients received Acthar prescriptions within 30 days of the index dates and 132 were treated with PMP or IVIG (Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). In the 24-month analysis, no patients were excluded, because they received treatment with PMP or IVIG prior to receiving Acthar prescriptions, but ten patients who received Acthar prescriptions more than 30 days after their index exacerbations were excluded.

Fig. 1.

Study participant flow for the 12-month analysis. PMP plasmapheresis, IVIG intravenous immunoglobulin, IVMP intravenous methylprednisolone

Patients with 12-month outcomes who received Acthar prescriptions were similar to those who received PMP or IVIG in terms of age, gender, type of health insurance plan, region, and most comorbidities, but patients who received Acthar prescriptions were less likely to have a diagnosis of diabetes without complications (7% vs. 14%; P = 0.03) and patients whose index relapse occurred in later years of the study were more likely to have received Acthar prescriptions (Table 2). Furthermore, patients who received Acthar prescriptions had fewer outpatient services and hospitalizations in the six months prior to the index exacerbation, but filled more prescriptions for all drugs in that time period (Table 2). When we analyzed patients with MS with 24 months of continuous enrollment (Table S1 in the supplementary material), we found that patients who received Acthar prescriptions were similar to those who received PMP or IVIG in most respects, but patients who received Acthar prescriptions were more likely to have comorbid hemiplegia (P = 0.01) and to have lived in the north central or southern US (P = 0.01). Similar to the 12-month outcomes cohort, patients who received Acthar prescriptions in the 24-month cohort had fewer outpatient services and hospitalizations but more medications in the 6 months prior to the index exacerbation. In the cohort of patients with 12-month outcomes, three patients received both Acthar and IVIG within 30 days, and one patient received both Acthar and PMP within 30 days. In the cohort of patients with 24-month outcomes, one patient received both Acthar and IVIG within 30 days and no patients received both Acthar and PMP within 30 days of the index exacerbation.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with MS with 12-month outcomes receiving Acthar prescriptions compared to those receiving PMP or intravenous IVIG within 30 days of exacerbation

| Characteristics | Acthar Rxa

n = 213 (49%) |

PMP or IVIGb

n = 226 (51%) |

P valuec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD (range) | 43.6 ± 10 (18–63) | 43.0 ± 11 (10–63) | 0.57 |

| Female | 168 (79%) | 184 (81%) | 0.50 |

| Type of health plan | 0.83 | ||

| Comprehensive | 7 (3.5%) | 6 (3%) | |

| Exclusive/preferred provider organization | 136 (67%) | 150 (67%) | |

| Health maintenance organization | 28 (14%) | 31 (14%) | |

| Point of service | 18 (8.9%) | 25 (11%) | |

| Consumer-directed/high-deductible | 14 (6.9%) | 11 (5%) | |

| Missing | 10 (4.6%) | 3 (1%) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.19 | ||

| 0 | 131 (62%) | 130 (58%) | |

| 1 | 42 (20%) | 49 (22%) | |

| 2 | 24 (11%) | 18 (8%) | |

| 3+ | 16 (7.5%) | 29 (13%) | |

| Comorbidity groups | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 2 (0.9%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.62 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2 (0.9%) | 2 (0.9%) | 1.0 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 8 (3.7%) | 6 (2.7%) | 0.55 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 18 (8.5%) | 27 (12%) | 0.23 |

| Dementia | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | NA |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 39 (18%) | 36 (16%) | 0.51 |

| Rheumatoid diseases | 12 (5.5%) | 17 (8%) | 0.38 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 3 (1.4%) | 5 (2.2%) | 0.72 |

| Chronic liver disease | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1.0 |

| Diabetes without complications | 16 (7.3%) | 31 (14%) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes with complications | 2 (0.9%) | 5 (2.2%) | 0.45 |

| Hemiplegia | 13 (6.1%) | 10 (4.4%) | 0.43 |

| Renal disease | 3 (1.4%) | 5 (2.2%) | 0.73 |

| Non-metastatic cancer | 4 (1.9%) | 13 (5.8%) | 0.05 |

| Sequelae of chronic liver disease | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1.0 |

| Metastatic cancer | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.49 |

| AIDS | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | NA |

| Geographic region | |||

| Northeast | 47 (22%) | 48 (22%) | 0.10 |

| North Central | 44 (20%) | 44 (20%) | |

| South | 90 (42%) | 93 (43%) | |

| West | 28 (13%) | 30 (14%) | |

| Missing | 4 (1.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Year of second MS exacerbation | |||

| 2007 | 0 | 14 (6%) | <0.0001 |

| 2008 | 2 (0.9%) | 51 (23%) | |

| 2009 | 14 (6.4%) | 55 (24%) | |

| 2010 | 36 (16%) | 49 (22%) | |

| 2011 | 76 (36%) | 36 (16%) | |

| 2012 | 85 (40%) | 21 (9%) | |

| Prior 6 months healthcare utilization, mean ± SD (range) | |||

| Outpatient services | 8.6 ± 7.0 (0–45) | 12 ± 8 (0–36) | <0.0001 |

| Hospitalizations | 0.05 ± 0.3 (0–3) | 0.3 ± 0.5 (0–3) | <0.0001 |

| Medications | 11.7 ± 9.2 (0–60) | 8.2 ± 8.8 (0–78) | <0.0001 |

Values are given as n (%) unless otherwise stated

IVIG intravenous immunoglobulin, MS multiple sclerosis, PMP plasmapheresis, Rx prescription, SD standard deviation

aThree patients who received Acthar prescriptions also received IVIG within 30 days and 1 also received PMP within 30 days

bBy definition, patients who received treatment with PMP or IVIG could not have received Acthar prescriptions

cChi-square test used for categorical variables; t test used for continuous variables

When we examined unadjusted 12-month outcomes (Table 3) among patients who received Acthar prescriptions compared to those who received PMP or IVIG, we found that patients who received Acthar prescriptions had, on average, 0.4 fewer hospitalizations (95% CI −0.6 to −0.2) and 17 fewer outpatient services (95% CI −23 to −11). Patients who received Acthar prescriptions had 14 more prescription medication fills (95% CI 8 to 20) on average. We found that patients who received Acthar prescriptions had, on average, shorter lengths of stay in the hospital (3.3 days less; 95% CI −0.2 to −6.5) and $15,300 lower inpatient costs (95% CI −$24,000 to −$6500) relative to patients who received PMP or IVIG. Patients who received Acthar prescriptions also had $54,100 lower outpatient costs (95% CI −$80,000 to −$28,000), $74,900 (95% CI $67,000 to $83,000) greater medication costs, but similar average total costs relative to patients who received PMP or IVIG ($5500 higher for Acthar patients; 95% CI −$22,000 to $34,000). Although the costs of medications were increased in the group that received Acthar prescriptions, these costs were offset by 93% (among the cohort with 12 months of follow-up) and 132% (among the cohort with 24 months of follow-up) by the relative decrease in inpatient and outpatient costs among the group that received Acthar prescriptions.

Table 3.

Number and costs of unadjusted 12-month outcomes among patients who received Acthar prescriptions compared to patients who received PMP or IVIG

| 12-month outcome | Unadjusted mean for patients receiving Acthar, mean (median) ± SD (range) | Unadjusted mean for patients receiving PMP or IVIG, mean (median) ± SD (range) | Difference in means for patients receiving Acthar vs. PMP/IVIG (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of all healthcare services | 78 (69) ± 49 (7–385) | 82 (70) ± 49 (9–300) | −4 (−13, 6) | 0.45 |

| Number of Hospitalizations | 0.2 (0) ± 0.6 (0–4) | 0.6 (0) ± 1.5 (0–9) | −0.4 (−0.6, −0.2) | 0.0002 |

| Length of stay (days)a | 3.7 (3) ± 3.6 (0–19) | 7.0 (4) ± 8 (0–45) | −3.3 (−0.2, −6.5) | 0.01 |

| Number of admissions to ICUa | 0.1 (0) ± 0.3 (0–1) | 0.2 (0) ± 0.5 (0–2) | −0.1 (−0.1, 0.3) | 0.18 |

| Number of ER visits | 0.5 (0) ± 1.2 (0–10) | 0.7 (0) ± 1.8 (0–18) | −0.2 (−0.5, 0.1) | 0.24 |

| Number of MS-related ER visitsb | 0.8 (1) ± 1.1 (0–6) | 0.9 (1) ± 1.3 (0–6) | 0.1 (−0.3, 0.6) | 0.52 |

| Number of outpatient services | 31 (23) ± 32 (2–366) | 48 (41) ± 29 (5–170) | −17 (−23, −11) | <0.0001 |

| Number of rehab and long-term care facilities servicesc | 0.1 (0) ± 1.3 (0–19) | 0.3 (0) ± 2.8 (0–40) | −0.2 (−0.6, 0.2) | 0.29 |

| Number of prescriptions | 47 (39) ± 33 (1–179) | 33 (27) ± 34 (0–230) | 14 (8, 20) | <0.0001 |

| Inpatient costs ($) | 3500 (0) ± 14,000 (0–124,000) | 18,800 (0) ± 63,000 (0–490,000) | −15,300 (−24,000, −6500) | 0.001 |

| Outpatient costs ($) | 30,300 (10,200) ± 175,000 (300–2,500,000) | 84,400 (61,000) ± 89,000 (2000–886,000) | −54,100 (−80,000, −28,000) | <0.0001 |

| Long-term care costs ($)d | 19 (0) ± 180 (0–2100) | 329 (0) ± 4000 (0–60,000) | −310 (−850, 230) | 0.26 |

| Medication costs ($) | 87,200 (78,600) ± 55,000 (0–440,000) | 12,300 (4000) ± 18,000 (0–111,000) | 74,900 (67,000, 83,000) | <0.0001 |

| Total costs ($) | 121,000 (94,400) ± 180,000 (3400–2,580,000) | 115,500 (86,000) ± 110,000 (4000–940,000) | 5500 (−22,000, 34,000) | 0.69 |

| 12-month outcome | Frequency (%) among patients receiving Acthar | Frequency (%) among patients receiving PMP or IVIG | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Readmission within 30 days (yes/no)a | 7 (29%) | 20 (29%) | 1.0 (0.4–2.7) | 0.98 |

CI confidence interval, ER emergency room, ICU intensive care unit, IVIG intravenous immunoglobulin, MS multiple sclerosis, PMP plasmapheresis

aLength of stay, admissions to ICU, and readmissions within 30 days calculated only among patients with at least one hospitalization (n = 27 among Acthar patients; n = 65 among PMP/IVIG patients)

bMS-related ER visits only calculated among patients with at least 1 ER visit (n = 58 among Acthar patients; n = 63 among PMP/IVIG patients)

cThis includes rehab facilities (inpatient and outpatient), skilled nursing facilities, inpatient long-term care, nursing facilities, custodial care facilities

dLong-term care costs are subsets of outpatient costs

Following adjustment for significant demographic variables, we found that patients who received Acthar received 3.2 fewer healthcare services overall on average (95% CI −5.2 to −1.1), 0.2 fewer mean hospitalizations (95% CI −0.3 to −0.1), shorter lengths of hospital stay (3.7 days less; 95% CI −4.8 to −1.1), 15 fewer outpatient services (95% CI −20 to −10), and similar total costs (Acthar total costs were $3000 lower; 95% CI −$21,000 to $15,000) compared to patients who received PMP or IVIG (Table 4). In addition, following adjustment, we found patients who received Acthar prescriptions had, on average, increased numbers of prescriptions filled (six more prescriptions; 95% CI 4–7) over the 12-month study period. Similar unadjusted and adjusted results were also observed when we examined patients who received Acthar prescriptions compared to patients who received PMP or IVIG with 24 months of continuous enrollment except we did not observe statistically significantly reduced lengths of stay in the hospital (Tables S2 and S3 in the supplementary material).

Table 4.

Adjusted 12-month outcomes among patients who received Acthar prescriptions compared to patients who received PMP or IVIG

| 12-month outcome | Adjusted mean (95% CI) for patients receiving Acthara | Adjusted mean (95% CI) for patients receiving PMP/IVIGa | Adjusted difference in means for patients receiving Acthar vs. PMP/IVIG (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of all healthcare services | 73 (71, 74) | 76 (74, 77) | −3.2 (−5.2, −1.1) | 0.003 |

| Number of hospitalizations | 0.2 (0.1, 0.3) | 0.4 (0.3, 0.5) | −0.2 (−0.3, −0.1) | 0.01 |

| Length of stay (days)b | 3.0 (1.9, 4.7) | 5.7 (4.2, 8.0) | −3.7 (−4.8, −1.1) | 0.01 |

| # of Admissions to ICUb | 0.05 (0.01. 0.37) | 0.09 (0.03, 0.23) | −0.4 (−0.08, 0.40) | 0.66 |

| Number of ER visits | 0.4 (0.3, 0.5) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7) | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.04) | 0.12 |

| Number of MS-related ER visitsc | 0.6 (0.5, 1.0) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.2) | −0.2 (−0.4, 0.3) | 0.36 |

| Number of outpatient services | 29 (26, 33) | 43 (39, 46) | −15 (−20, −10) | <0.0001 |

| Number of rehab and long-term care facilities services | 0.04 (0.02, 0.07) | 0.23 (0.17, 0.32) | −0.19 (−0.26, −0.12) | <0.0001 |

| Number of prescriptions | 36 (35, 38) | 30 (29, 31) | 6 (4, 7) | <0.0001 |

| Total costs of services ($) | 106,400 (93,000, 121,000) | 109,400 (99,000, 121,000) | −3000 (−21,000, 15,000) | 0.74 |

| 12-month outcome | Adjusted mean (95% CI) for patients receiving Acthara | Adjusted mean (95% CI) for patients receiving PMP/IVIGa | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Readmission within 30 days (yes/no)b | 0.3 (0.02, 0.6) | 0.2 (0.02, 0.4) | 1.4 (0.3, 7.7) | 0.68 |

CI confidence interval, ER emergency room, ICU intensive care unit, IVIG intravenous immunoglobulin, PMP plasmapheresis, MS multiple sclerosis

aAdjusted for the number of relapses prior to index date, days between exacerbations, comorbid diabetes without complications, year of index exacerbation, and number of outpatient services, hospitalizations, and medications in the 6 months prior to the index exacerbation

bLength of stay, admissions to ICU, and readmissions within 30 days calculated only among patients with at least 1 hospitalization

cMS-related ER visits only calculated among patients with at least 1 ER visit

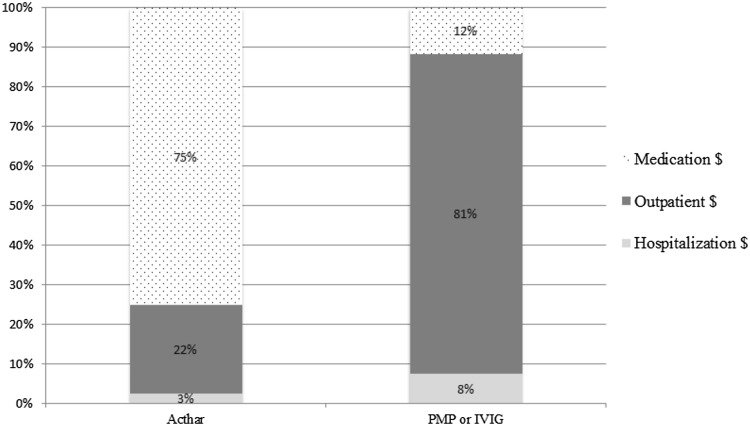

Estimated proportions of adjusted costs, categorized into medication, outpatient, and hospitalization costs are shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. S2 (in the supplementary material). Medication costs comprised the greatest proportion of the total costs in Acthar prescription recipients in both the 12- and the 24-month cohorts. For PMP/IVIG recipients, outpatient costs comprised the greatest proportion of the total costs in both cohorts.

Fig. 2.

Adjusted (for number of relapses prior to index date, days between exacerbations, comorbid diabetes without complications, year of index exacerbation, and number of outpatient services, hospitalizations, and medications in the 6 months prior to the index exacerbation) proportions of 12-month cost components among patients with multiple sclerosis who were prescribed Acthar compared to those who received PMP or IVIG. PMP plasmapheresis, IVIG intravenous immunoglobulin

Discussion

Compared to patients who received PMP or IVIG for MS exacerbations, adjusted analyses showed that patients who received Acthar prescriptions tended to utilize fewer inpatient and outpatient healthcare services. While patients who received Acthar prescriptions received more prescription medications of any type and had higher proportions of medication costs compared to patients who received PMP or IVIG, total adjusted costs were similar between the two groups. These results remained when we examined patients who were enrolled in our cohort for 24 months continuously.

The mechanism of action of Acthar continues to be explored as current research suggests Acthar may have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties [15, 20]. Some research has shown that Acthar may benefit patients who do not respond to or tolerate other treatments [21]. While large or long-term trials assessing the use of Acthar for treating MS relapses have not been conducted, the current evidence shows it may have an important role by, for example, minimizing inpatient admissions, which have been associated with MS-related costs [22].

This study had several limitations. First, because we defined exposure to Acthar using outpatient prescription claims data, it is possible that some patients were subject to misclassification, because they did not actually inject the medication. Furthermore, because this was an observational study and not a randomized controlled trial, we cannot be certain that the differences we observed between patients who did and did not receive Acthar prescriptions were not affected by confounding factors. We corrected for this by adjusting our models for potentially confounding variables, but unmeasured factors might have played a role in the associations that we reported. In addition, although we made direct comparisons between treatment with Acthar versus treatment with IVIG or PMP, the determination of the efficacies of IVIG and PMP to treat MS relapses is ongoing [14, 17, 23]. Because we were interested in outcomes that occurred over the 12 and 24 months the subsequent MS exacerbation, we excluded patients who were not enrolled in their health plans for one or two years after the index event, so our population was stable by definition, and our results are likely not generalizable to more transient populations. In addition, since we included only patients who experienced multiple relapses and who received treatments besides IVMP for their subsequent relapses, our sample size was fairly small and our results are not generalizable to the broader MS population that responds to IVMP. In addition, although we closely followed a pre-determined analysis plan, we were not blinded to whether subjects received Acthar or PMP/IVIG when we performed the analyses. We also did not have information on procedures or health utilizations for which patients paid out-of-pocket rather than filing claims through their insurance companies, and our cost estimates might, therefore, be conservative. Furthermore, the population of patients in the MarketScan databases is not randomly sampled and some populations, such as patients insured by small employers or patients who do not have insurance (or do not have spouses with insurance) were not represented in this study population. Therefore, these results may not be generalizable across all patients with MS in the US. Finally, as with any claims-based study, our data may have included coding errors with diagnoses or procedures.

Conclusions

Using the medical and pharmacy claims from Truven Health Analytics MarketScan Databases, we assessed resource utilization, outcomes, and costs in patients with MS experiencing multiple relapses. Compared to patients using PMP or IVIG, patients receiving Acthar prescriptions had fewer outpatient services and hospitalizations, and similar overall costs. Although further studies are necessary to confirm these findings and decisions about treatment for MS relapses must be tailored to specific patients’ clinical factors, Acthar may be a useful treatment option for patients with MS experiencing relapses who are unable to be treated with IVMP. Further research should be conducted to determine its cost-effectiveness in MS relapse treatment compared to other agents.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant to the University of Washington from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. The article processing charges and open access fee for this publication were funded by Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) requirements for authorship for this manuscript. We also take responsibility for the integrity of this work as a whole and all authors have given final approval for the version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures

Patricia B. Schepman is a former employee of Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. Kavitha Damal is a former consultant of Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. Ryan N. Hansen has served on a health economics and outcomes research advisory board for Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals and has received research grant funding from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. Laura S. Gold and Kangho Suh declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. This study was exempt from review by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (IRB) through self-determination.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/AAD4F06050B69811.

References

- 1.Luzzio C, Dangond F, Keegan B. Multiple sclerosis: clinical presentation. 2012. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1146199-clinical. Accessed 2 May 2016.

- 2.(MSIF) MSIF. Atlas of MS 2013: mapping multiple sclerosis around the world (pdf). Multiple Sclerosis International Federation, 2013. http://www.msif.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Atlas-of-MS.pdf.

- 3.Gilden DM, Kubisiak J, Zbrozek AS. The economic burden of medicare-eligible patients by multiple sclerosis type. Value Health. 2011;14(1):61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owens GM, Olvey EL, Skrepnek GH, Pill MW. Perspectives for managed care organizations on the burden of multiple sclerosis and the cost-benefits of disease-modifying therapies. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(1 Suppl A):S41–S53. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.s1.S41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll CA, Fairman KA, Lage MJ. Updated cost-of-care estimates for commercially insured patients with multiple sclerosis: retrospective observational analysis of medical and pharmacy claims data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:286. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parise H, Laliberte F, Lefebvre P, et al. Direct and indirect cost burden associated with multiple sclerosis relapses: excess costs of persons with MS and their spouse caregivers. J Neurol Sci. 2013;330(1–2):71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vickrey BG, Lee L, Moore F, Moriarty P. EDSS change relates to physical HRQoL while relapse occurrence relates to overall HRQoL in patients with multiple sclerosis receiving subcutaneous interferon beta-1a. Mult Scler Int. 2015;2015:631989. doi: 10.1155/2015/631989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casado V, Martinez-Yelamos S, Martinez-Yelamos A, et al. The costs of a multiple sclerosis relapse in Catalonia (Spain) Neurologia. 2006;21(7):341–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell JD, Ghushchyan V, Brett McQueen R, et al. Burden of multiple sclerosis on direct, indirect costs and quality of life: National US estimates. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3(2):227–236. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonafede MM, Johnson BH, Wenten M, Watson C. Treatment patterns in disease-modifying therapy for patients with multiple sclerosis in the United States. Clin Ther. 2013;35(10):1501–1512. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.07.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Page E, Veillard D, Laplaud DA, et al. Oral versus intravenous high-dose methylprednisolone for treatment of relapses in patients with multiple sclerosis (COPOUSEP): a randomised, controlled, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):974–981. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nickerson M, Cofield SS, Tyry T, Salter AR, Cutter GR, Marrie RA. Impact of multiple sclerosis relapse: the NARCOMS participant perspective. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4(3):234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bayry J, Hartung HP, Kaveri SV. IVIg for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: promises and uncertainties. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36(7):419–421. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cortese I, Chaudhry V, So YT, Cantor F, Cornblath DR, Rae-Grant A. Evidence-based guideline update: plasmapheresis in neurologic disorders: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2011;76(3):294–300. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318207b1f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross AP, Ben-Zacharia A, Harris C, Smrtka J. Multiple sclerosis, relapses, and the mechanism of action of adrenocorticotropic hormone. Front Neurol. 2013;4:21. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2013.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ontaneda D, Rae-Grant AD. Management of acute exacerbations in multiple sclerosis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2009;12(4):264–272. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.58283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elovaara I, Apostolski S, van Doorn P, et al. EFNS guidelines for the use of intravenous immunoglobulin in treatment of neurological diseases: EFNS task force on the use of intravenous immunoglobulin in treatment of neurological diseases. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(9):893–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin SR, Wong YN, Uzzo RG, Beck JR, Egleston BL. Why summary comorbidity measures such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index and Elixhauser score work. Med Care. 2013;53(9):e65–e72. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318297429c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lal R, Bell S, Challenger R, et al. Pharmacodynamics and tolerability of repository corticotropin injection in healthy human subjects: a comparison with intravenous methylprednisolone. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;56(2):195–202. doi: 10.1002/jcph.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berkovich R. Treatment of acute relapses in multiple sclerosis. Neurother J Am Soc Exp Neurother. 2013;10(1):97–105. doi: 10.1007/s13311-012-0160-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien JA, Ward AJ, Patrick AR, Caro J. Cost of managing an episode of relapse in multiple sclerosis in the United States. BMC Health Serv Res. 2003;3(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elovaara I, Kuusisto H, Wu X, Rinta S, Dastidar P, Reipert B. Intravenous immunoglobulins are a therapeutic option in the treatment of multiple sclerosis relapse. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34(2):84–89. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e31820a17f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.