Abstract

Introduction

Using cross-sectional survey data, we assessed the association between chronic illness burden and health-related self-efficacy, evaluating whether patient-centered communication is associated with self-efficacy and if that relationship varies by chronic illness burden.

Methods

Data were from the Health Information National Trends Survey, a cross-sectional survey of the US adult population collected in 2012–2013 (n = 3630). Health-related self-efficacy was measured with the item: “Overall, how confident are you about your ability to take good care of your health?” and the prevalence of six chronic conditions and depression/anxiety was assessed. Patient-centered communication was measured as the frequency with which respondents perceived their healthcare providers allowed them to ask questions, gave attention to their emotions, involved them in decisions, made sure they understood how to take care of their health, helped them to deal with uncertainty, and if they felt they could rely on their healthcare providers to take care of their healthcare needs.

Results

Health-related self-efficacy was significantly lower among individuals with greater illness burden. In adjusted analysis, individuals who experienced more positive patient-centered communication reported higher levels of self-efficacy (β = 0.26, P < 0.0001); this association was strongest among those with greater illness burden.

Conclusion

Higher levels of self-efficacy were observed among patients reporting more positive patient-centered communication; the observed association was stronger among those with greater chronic illness burden.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-016-0369-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Multi-morbidity, Multiple chronic conditions, Patient-centered communication, Self-efficacy, Survey

Introduction

Patients with multiple chronic illnesses face significant demands in managing their illnesses [1–3]. Effective patient self-management has been linked to improvements in health outcomes for a number of chronic conditions [4–10]. Prevalent mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, often co-exist with chronic physical conditions [11–14]. Co-occurrence of mental and physical illness has been associated with greater functional impairment, higher symptom burden, poorer quality of life, and poorer health outcomes [15, 16]. Emerging evidence suggests that the risks of poor health outcomes among persons who suffer from the co-occurrence of physical and mental health conditions appears to be synergistic rather than additive [17, 18]. An emerging focus in clinical care for patients with multiple chronic illnesses is on improving quality of life, increasing functional capability, and preventing complications and further deterioration through enhancing patients’ self-management abilities [19, 20]. Prior research has consistently identified self-efficacy, an individual’s sense of personal control over behavior change, [21] as playing a critical role in patient self-management [22–25]. It has been argued that such efforts should be focused on improving communication between patients and their care providers [25].

A growing body of evidence supports the relationship between patient-centered communication and improvements in adherence to treatment recommendations, management of chronic disease, quality of life, and health outcomes [26–31]. Caring for patients with multiple chronic conditions requires effective communication and coordination among members of the care team and with the patient and their informal caregivers. Patient-centered communication has been conceptualized as serving the following six functions: fostering healing relationships through the development of trust, mutual understanding, and empathy; exchanging information while demonstrating sensitivity to patients’ information needs, issues of literacy, numeracy, and culture; responding to emotions by acknowledging and offering support for patients’ emotional reactions during illness, treatment, and recovery; assisting patients and their families in managing uncertainty around disease, treatment efficacy, and prognosis; engaging patients and relevant others in making decisions through open exchange of information; and enabling patient self-management by helping patients navigate the healthcare system, by identifying community resources, and by encouraging patient autonomy, self-efficacy, and self-care outside of the clinical encounter [30].

We evaluated the overall burden of multiple chronic conditions and depression/anxiety and differences in illness burden by sociodemographic subgroups and healthcare access in the population. We then examined whether health-related self-efficacy varies by chronic illness burden and by the experience of patient-centered communication. We also assessesed whether the association between patient-centered communication and health-related self-efficacy varies by chronic illness burden.

Methods

Data were from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS 4, Cycle 2), a cross-sectional survey of the US adult population [32]. Data were collected by mailed questionnaire between October 2012 and January 2013 (response rate = 40.0%; n = 3630). This study was approved by the Westat institutional review board (IRB) in an expedited review in 2010, and deemed exempt from IRB review by the NIH Office of Human Subjects Research in 2011.

Survey Items

Sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, annual household income, marital status, immigrant status, and urban/rural designation were included in the current analyses, as we expected all to potentially affect communication, self-efficacy, and their association.

Respondents were asked if they had a usual source of healthcare: “Not including psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, is there a particular doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you see most often”? Health insurance status was also assessed: “Do you have any kind of health care coverage, including health insurance, prepaid plans such as HMOs [health maintenance organizations], or government plans such as Medicare?” Participants were also asked to indicate how frequently they had seen a doctor, nurse, or other healthcare professional during the prior year.

The number of chronic conditions was assessed with a series of (yes/no) items that asked respondents “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you had any of the following conditions: diabetes or high blood sugar; high blood pressure or hypertension; a heart condition such as heart attack, angina, or congestive heart failure; chronic lung disease, asthma, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis; arthritis or rheumatism; and depression or anxiety disorder.” Respondents were also asked “Have you ever been diagnosed as having cancer?” (yes/no); if they responded affirmatively, they were asked to indicate the type(s) of cancer diagnoses by marking “all that apply.” We included all cancer diagnoses in our counts of chronic physical conditions. Given emerging evidence that the co-occurrence of mental and physical illness may have a synergistic impact on health outcomes, we did not include depression and anxiety in our summative count measure of chronic illness. Rather, we treated physical and mental health separately in our analyses.

Respondents were asked to rate their confidence in their ability to take care of their health. Response options were on a five-point scale as follows: completely confident, very confident, somewhat confident, a little confident, and not confident at all. For the ease of interpretation, responses were reverse scored and a continuous efficacy score was created using a linear transformation into a 0–100 scale, where higher scores indicate greater efficacy.

Respondents were asked about their communication experiences during the prior 12 months with doctors, nurses, or other health professionals [33]. These items were grounded in a patient-centered communication framework originally proposed by Epstein and Street [30]. Specifically, respondents were asked “How often did doctors, nurses, or other health professionals …”: “… give you the chance to ask all the health-related questions you had?”; “… give the attention you needed to your feelings and emotions?”; “… involve you in decisions about your health care as much as you wanted?”; “… make sure you understood the things you needed to do to take care of your health?”; “… help you deal with feelings of uncertainty about your health or health care?” Respondents were also asked: “During the past 12 months, how often did you feel you could rely on your doctors, nurses, or other health care professionals to take care of your health care needs?” Response options were on a four-point scale: always, usually, sometimes, and never. Responses to these items were reverse scored and summed into a composite score with a linear transformation into a 0–100 scale with higher scores indicating more positive communication with providers (Cronbach’s α = 0.92) [34].

Analysis

Analyses included participants who visited a healthcare professional during the last 12 months (n = 3000). Survey procedures in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) were used to account for survey complexity and to apply sample and replicate weights. Chi-square was used to assess the frequency and distribution of the outcome variables by sociodemographic and healthcare variables. Multiple linear regression was used to examine the relationship between predictors and outcome variables, adjusting for sociodemographic and healthcare characteristics.

Results

The weighted population estimates for sociodemographic characteristics, healthcare access and use, and chronic conditions are summarized in Table 1. As per the sampling strategy and weighting scheme, the sociodemographic characteristics of the population are representative of the US population. The majority of our population indicated having a usual source of healthcare and some type of health insurance. Nearly half of the population reported that they saw a healthcare provider once or twice during the last 12 months. The population frequently indicated suffering from the following chronic conditions: high blood pressure, arthritis, depression/anxiety, lung disease, and diabetes.

Table 1.

Sample size and weighted population estimates of sociodemographic and healthcare characteristics of respondents

| Respondent characteristics | Un-weighted frequency | Weighted %a |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1093 | 45.3 |

| Female | 1852 | 54.7 |

| Missing | 55 | 1.4 |

| Age, years | ||

| 18–49 | 1087 | 55.1 |

| 50–64 | 981 | 26.4 |

| 65+ | 846 | 18.5 |

| Missing | 86 | 2.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| NH, white | 1744 | 69.7 |

| NH, black | 417 | 10.9 |

| NH, other | 162 | 6.0 |

| Hispanic | 385 | 13.3 |

| Missing | 292 | 8.0 |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 907 | 33.3 |

| Some college | 859 | 38.0 |

| College graduate or more | 1168 | 28.7 |

| Missing | 66 | 1.9 |

| Income | ||

| <$20,000 | 669 | 21.6 |

| $20,000–$49,999 | 868 | 29.5 |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 847 | 29.6 |

| $100,000 or more | 528 | 19.2 |

| Missing | 88 | 2.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/living as married | 1570 | 58.0 |

| Single, never been married | 488 | 26.5 |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 861 | 15.8 |

| Missing | 81 | 2.1 |

| Born in US | ||

| Yes | 2583 | 88.5 |

| No | 374 | 11.5 |

| Missing | 43 | 1.4 |

| Rural/urban (USDA) | ||

| Metropolitan country | 2531 | 83.1 |

| Non-metropolitan (population ≥20,000) | 175 | 6.2 |

| Non-metropolitan (population <20,000) | 294 | 10.7 |

| Healthcare access and use | ||

| Usual source of healthcare | ||

| Yes | 2287 | 73.2 |

| No | 695 | 26.8 |

| Missing | 18 | 0.6 |

| Health insurance status | ||

| Insured | 2628 | 87.3 |

| Not insured | 364 | 12.7 |

| Missing | 8 | 0.3 |

| Number of healthcare visits | ||

| 1–2 | 1260 | 45.3 |

| 3–4 | 995 | 29.6 |

| 5+ | 745 | 25.0 |

| Chronic illness | ||

| Diabetes | ||

| Yes | 601 | 16.3 |

| No | 2286 | 83.7 |

| Missing | 113 | 3.3 |

| High blood pressure | ||

| Yes | 1339 | 38.2 |

| No | 1562 | 61.8 |

| Missing | 99 | 3.2 |

| Heart condition | ||

| Yes | 334 | 8.4 |

| No | 2566 | 91.6 |

| Missing | 100 | 3.2 |

| Lung disease | ||

| Yes | 447 | 16.6 |

| No | 2451 | 83.4 |

| Missing | 102 | 3.2 |

| Arthritis | ||

| Yes | 939 | 26.4 |

| No | 1956 | 73.6 |

| Missing | 105 | 3.3 |

| Cancer | ||

| Yes | 419 | 9.3 |

| No | 2560 | 90.7 |

| Missing | 21 | 0.6 |

| Depression/anxiety | ||

| Yes | 738 | 26.4 |

| No | 2160 | 73.6 |

| Missing | 102 | 3.4 |

NH non-Hispanic, USDA US Department of Agriculture

aSample and replicate weights were applied to account for the complex survey design and to ensure estimates are representative of the US population

Table 2 summarizes sociodemographic and healthcare characteristics by the number of chronic conditions and by prior diagnosis of anxiety or depression. A greater number of chronic conditions were observed with increasing age, among persons who were divorced, separated, or widowed, and among those reporting a greater number of visits to a healthcare provider during the last 12 months. Fewer chronic conditions were observed with increasing education and increasing income. Regarding usual source of care, there appeared to be a greater number of people reporting that they did not have a usual source of care when they had only one condition, but that trend reversed for people reporting that they had at least two conditions. Those with multiple chronic conditions more frequently reported having a usual source of care than those with one condition. Depression or anxiety was more frequently reported among: women, Whites, those with at least some college education, those earning less than $20,000 per year, those born in the US, and those reporting five or more visits to healthcare providers during the last 12 months (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate associations between sociodemographic and healthcare characteristics and burden of chronic illness and depression/anxiety

| Respondent characteristics | Number of comorbid conditions | Chi-square P value |

Depression/anxiety | Chi-square P value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (%) | 1 (%) | 2 (%) | 3+ (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | |||

| Sex | 0.9857 | 0.0005 | ||||||

| Male | 40.9 | 26.6 | 18.5 | 14.0 | 78.9 | 21.1 | ||

| Female | 39.9 | 27.1 | 19.0 | 13.9 | 69.1 | 30.9 | ||

| Age, years | <0.0001 | 0.1104 | ||||||

| 18–49 | 58.5 | 25.7 | 11.9 | 3.9 | 72.3 | 27.7 | ||

| 50–64 | 26.6 | 32.1 | 25.6 | 18.8 | 71.9 | 28.1 | ||

| 65+ | 9.6 | 23.5 | 29.0 | 37.8 | 78.7 | 21.3 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.2318 | 0.0193 | ||||||

| NH, white | 39.8 | 26.8 | 19.2 | 14.1 | 71.1 | 28.9 | ||

| NH, black | 39.8 | 27.8 | 20.4 | 12.0 | 82.5 | 17.5 | ||

| NH, other | 54.8 | 23.1 | 15.6 | 6.4 | 80.2 | 19.8 | ||

| Hispanic | 44.9 | 29.7 | 11.9 | 13.6 | 78.3 | 21.7 | ||

| Education | <0.0001 | 0.0032 | ||||||

| High school or less | 27.5 | 27.4 | 23.7 | 21.4 | 74.4 | 25.6 | ||

| Some college | 45.5 | 22.3 | 19.2 | 13.1 | 67.9 | 32.1 | ||

| College graduate or more | 47.7 | 32.6 | 12.5 | 7.2 | 79.5 | 20.5 | ||

| Income | <0.0001 | 0.0083 | ||||||

| <$20,000 | 27.9 | 23.2 | 26.0 | 22.9 | 63.5 | 36.5 | ||

| $20,000–$49,999 | 39.0 | 27.4 | 16.8 | 16.8 | 75.1 | 24.9 | ||

| $50,000–$99,999 | 43.3 | 28.0 | 16.8 | 11.9 | 75.7 | 24.3 | ||

| $100,000 or more | 50.9 | 28.2 | 16.2 | 4.7 | 75.5 | 21.5 | ||

| Marital status | <0.0001 | 0.0513 | ||||||

| Married/living as married | 40.0 | 27.0 | 18.2 | 14.9 | 76.5 | 23.5 | ||

| Single, never been married | 53.4 | 28.4 | 13.5 | 4.7 | 70.2 | 29.8 | ||

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 19.8 | 24.2 | 29.2 | 26.8 | 67.4 | 32.6 | ||

| Born in US | 0.1326 | 0.0134 | ||||||

| Yes | 39.5 | 26.6 | 19.4 | 14.6 | 72.5 | 27.5 | ||

| No | 46.3 | 28.5 | 13.7 | 11.5 | 80.8 | 19.2 | ||

| Rural/urban (USDA) | 0.0658 | 0.1732 | ||||||

| Metropolitan country | 40.8 | 27.8 | 18.7 | 12.7 | 73.1 | 26.9 | ||

| Non-metropolitan (population ≥20,000) | 44.0 | 18.1 | 19.1 | 18.8 | 82.5 | 17.5 | ||

| Non-metropolitan (population <20,000) | 33.8 | 24.2 | 20.5 | 21.5 | 72.4 | 27.6 | ||

| Regular healthcare provider | <0.0001 | 0.6384 | ||||||

| Yes | 36.4 | 27.0 | 20.0 | 16.6 | 73.0 | 27.0 | ||

| No | 51.1 | 26.8 | 15.0 | 7.1 | 75.0 | 25.0 | ||

| Health insurance status | 0.2508 | 0.5132 | ||||||

| Insured | 40.1 | 27.1 | 18.2 | 14.6 | 73.9 | 26.1 | ||

| Not insured | 40.8 | 25.3 | 23.7 | 10.3 | 71.2 | 28.8 | ||

| Number of healthcare visits | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 1–2 | 54.3 | 26.8 | 12.0 | 6.9 | 81.7 | 18.3 | ||

| 3–4 | 32.9 | 26.8 | 22.4 | 17.8 | 71.9 | 28.1 | ||

| 5+ | 23.1 | 26.8 | 27.4 | 22.7 | 60.9 | 39.1 | ||

NH non-Hispanic, USDA US Department of Agriculture

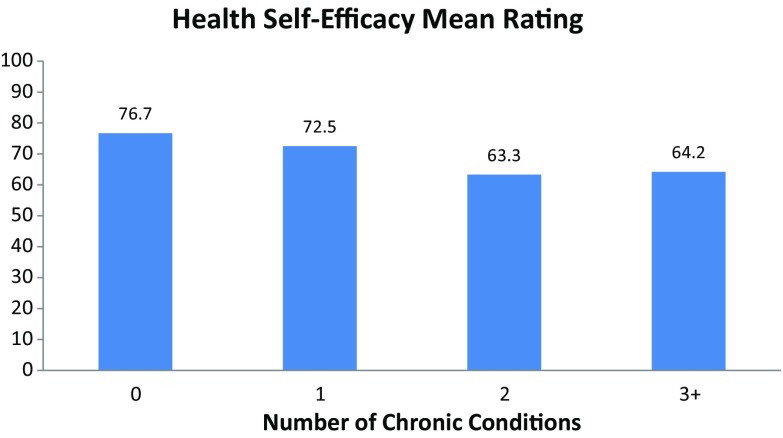

Mean ratings of healthcare self-efficacy, on a 100-point scale, decreased with an increasing number of chronic conditions (Fig. 1). Self-efficacy was also significantly lower among individuals who reported being diagnosed with depression or anxiety (mean = 65.3) compared to those who were not (mean = 73.4; P = 0.0003). Table 3 summarizes the results of a multivariable linear regression examining independent associations of the number of chronic conditions, depression/anxiety, and patient-centered communication with health self-efficacy controlling for sociodemographic and healthcare variables. The number of chronic conditions was significantly associated with health self-efficacy. Compared to those with three or more chronic conditions, those with zero conditions (β = 11.06, P < 0.0001) and one chronic condition (β = 7.82, P = 0.0002) had significantly higher ratings of health self-efficacy. Compared to those with depression/anxiety, those without depression/anxiety had significantly higher ratings of health self-efficacy (β = 4.34, P = 0.01). Finally, higher ratings of patient-centered communication were positively and significantly associated with health self-efficacy (β = 0.26, P < 0.0001).

Fig. 1.

Mean ratings of health self-efficacy by the number of chronic conditions

Table 3.

Multivariable linear regression examining independent associations of the number of chronic conditions, depression/anxiety, and patient-centered communication with health self-efficacy

| β | SE | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of chronic conditions | <0.0001 | ||

| 0 | 11.06 | 2.42 | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 7.82 | 1.96 | 0.0002 |

| 2 | 0.69 | 2.06 | 0.74 |

| 3+ | Reference | – | – |

| Depression or anxiety diagnosis | |||

| No | 4.34 | 1.69 | – |

| Yes | Reference | – | – |

| Patient-centered communication | 0.26 | 0.04 | <0.0001 |

Model adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, income, marital status, immigrant status, rural/urban designation, usual source of healthcare, health insurance status, and number of visits to healthcare provider during the last 12 months; values for control variables included in Online Appendix I

SE standard error

Table 4 summarizes the results of two separate multivariable linear regression models examining the independent associations of patient-centered communication with health self-efficacy by the number of chronic conditions (Model 1) and by depression/anxiety status (Model 2). Both models controlled for sociodemographic and healthcare variables, including indicators of socioeconomic status and insurance status. The association between patient-centered communication and health self-efficacy was significant and increased with increasing numbers chronic conditions. The association between patient-centered communication and health self-efficacy was greater among those with depression/anxiety (β = 0.39, P < 0.0001) than among those without (β = 0.19, P < 0.0001).

Table 4.

Multivariable linear regression models examining independent associations of patient-centered communication with health self-efficacy stratified by the number of chronic conditions and by depression/anxiety

| β | SE | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: number of chronic conditions | |||

| 0 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.0005 |

| 1 | 0.26 | 0.05 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 0.34 | 0.10 | 0.002 |

| 3+ | 0.35 | 0.08 | <0.0001 |

| Model 2: depression/anxiety | |||

| Yes | 0.39 | 0.09 | <0.0001 |

| No | 0.19 | 0.04 | <0.0001 |

Models adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, income, marital status, immigrant status, rural/urban designation, usual source of healthcare, health insurance status, and number of visits to healthcare provider during the last 12 months; values for control variables included in Online Appendix II (Model 1) and Online Appendix III (Model II)

SE standard error

Discussion

In our analysis of nationally representative data, individuals with greater chronic illness burden had lower confidence in taking care of their health. Higher scores on patient-centeredness with respect to experiences of clinician-patient communication were associated with higher levels of health self-efficacy. Moreover, the association between patient-centered communication and health-related self-efficacy was the strongest among those with the greatest number of chronic conditions. We also found that the association between patient-centered communication and health self-efficacy was greater among those with depression/anxiety compared to those without. These cross-sectional findings highlight the potential importance of patient-centered communication, particularly among persons managing multiple chronic illnesses and among patients with depression or anxiety. Future research is encouraged to examine whether patient-centered communication is causally associated with health self-efficacy among patients with multiple chronic illnesses.

Our findings are relevant to emerging models of care coordination for patients with multiple chronic illnesses [35], and among those with depression or anxiety [36]. Care coordination is designed to promote communication and information exchange among care providers, patients, and informal caregivers to optimally engage each in an integrated way throughout the care process. Effective care coordination can improve continuity of care and improve delivery of patient-centered care for patients with multiple chronic conditions [37, 38], and those with depression or anxiety [36]. Several evidence-based practices for care coordination have been recommended to optimize patient-centered outcomes. Many of these have relevance to the components of patient-centered communication that we found to be associated with patient self-efficacy, specifically information exchange, attention to emotions, and supporting patient self-management [35]. The association we observed between patient-centered communication and health self-efficacy adds to the emerging evidence that patient-centered communication may play a pivotal role in the successful implementation of effective care coordination models [35].

The data analyzed in our study are derived from national cross-sectional surveys; therefore, inferences about causality are not appropriate. It cannot be determined from our analyses whether patient-centered communication leads to improved health self-efficacy. It may be that individuals with high health self-efficacy are more likely to seek healthcare providers who deliver more patient-centered care. Further investigation of the nature of these associations and mechanisms driving health self-efficacy is warranted. The final response rate for this survey was fairly low, although comparable to other mailed surveys and an improvement over response rates from telephone surveys [39, 40]. While low response rates can lead to biases in the data, significant efforts were made to reduce potential for such bias through sampling and weighting [32, 41], and an emerging body of evidence suggests that the potential for bias resulting from declining response rates to health surveys may have less of a negative impact than previously thought [39, 42, 43]. While the HINTS survey is constructed of valid scales and rigorously tested survey items, fully capturing complex constructs, such as health-related self-efficacy and patient-centered communication, through national survey is challenging. Thus, although the survey items used to assess patient-centered communication were originally developed by the Agency for Healthcare and Quality Research for their Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) program and have been widely used to evaluate communication between healthcare providers and patients [44], it is important to recognize the limitations of assessing complex and dynamic interactions through survey research [45]. Our measure of health self-efficacy was derived from a single survey item, and was broadly applicable to taking care of ones health without reference to any specific health behavior. It is, therefore, unclear how this measure of health self-efficacy might apply to specific health self-management tasks. Further research is encouraged to explore the association between patient-centered communication and behavior-specific health self-efficacy. An additional limitation is that while we focused on the most commonly prevelant chronic conditions, our list of chronic conditions was not comprehensive. Furthermore, while we considered greater number of chronic conditions to be a proxy for greater illness burden, we did not collect data on subjective and/or objective measures of functional limitations that could have further quantified the actual illness burden experienced by survey respondents.

Conclusions

Systematic implementation of patient-centered communication and care processes has a significant potential to improve patients’ feelings of self-efficacy around managing their healthcare concerns, which may, in turn, improve their ability to effectively engage in self-management. Results of our study suggest the need for prospective studies of how healthcare delivery systems provide patients with ongoing support both during and in between encounters and to test whether facilitating a patient-centered approach in every patient–clinician interaction more effectively engages patients in their health and healthcare.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

HINTS was funded by contract # HHSN261201000064C from the National Cancer Institute. This study was funded, in part, by the Mayo Clinic Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery. This work was completed, while Dr. Arora was employed at the National Cancer Institute and does not reflect the policy or position of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The article processing charges for this publication were funded by the authors. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures

Lila J. Finney Rutten, Bradford W. Hesse, Jennifer L. St. Sauver, Patrick Wilson, Neetu Chawla, Danielle B. Hartigan, Richard P. Moser, Stephen Taplin, Russell Glasgow, and Neeraj K. Arora have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

HINTS 4 was approved by the Westat IRB in an expedited review in 2010, and deemed exempt from institutional review board (IRB) review by the NIH Office of Human Subjects Research in 2011.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/BCD4F0600F321DB3.

References

- 1.Gallacher K, May CR, Montori VM, Mair FS. Understanding patients’ experiences of treatment burden in chronic heart failure using normalization process theory. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(3):235–243. doi: 10.1370/afm.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.May C, Montori VM, Mair FS. We need minimally disruptive medicine. BMJ. 2009;339:b2803. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd CM, Wolff JL, Giovannetti E, Reider L, Weiss C, Xue QL, et al. Healthcare task difficulty among older adults with multimorbidity. Med Care. 2014;52(Suppl 3):S118–S125. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a977da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damush TM, Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Bosworth HB, Cheng E, Anderson J, et al. Implementing evidence-based patient self-management programs in the Veterans Health Administration: perspectives on delivery system design considerations. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(Suppl 1):68–71. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1123-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holman H, Lorig K. Patient self-management: a key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic disease. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(3):239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, Sobel DS, Brown BW, Jr, Bandura A, et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001;39(11):1217–1223. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4(6):256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, Brown BW, Jr, Bandura A, Ritter P, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care. 1999;37(1):5–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ory MG, Ahn S, Jiang L, Lorig K, Ritter P, Laurent DD, et al. National study of chronic disease self-management: six-month outcome findings. J Aging Health. 2013;25(7):1258–1274. doi: 10.1177/0898264313502531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ory MG, Ahn S, Jiang L, Smith ML, Ritter PL, Whitelaw N, et al. Successes of a national study of the chronic disease self-management program: meeting the triple aim of health care reform. Med Care. 2013;51(11):992–998. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a95dd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman C, Rice D, Sung HY. Persons with chronic conditions. Their prevalence and costs. JAMA. 1996;276(18):1473–1479. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540180029029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kronick RG, Bella M, Gilmer TP. The faces of medicaid III: refining the portrait of people with multiple chronic conditions. Hamilton, NJ: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.; 2009.

- 13.Neeleman J, Ormel J, Bijl RV. The distribution of psychiatric and somatic III health: associations with personality and socioeconomic status. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(2):239–247. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200103000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davydow DS, Levine DA, Zivin K, Katon WJ, Langa KM. The association of depression, cognitive impairment without dementia, and dementia with risk of ischemic stroke: a cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2015;77(2):200–208. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viron MJ, Stern TA. The impact of serious mental illness on health and healthcare. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(6):458–465. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(10)70737-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawrence D, Kisely S, Pais J. The epidemiology of excess mortality in people with mental illness. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(12):752–760. doi: 10.1177/070674371005501202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katon W, Pedersen HS, Ribe AR, Fenger-Gron M, Davydow D, Waldorff FB, et al. Effect of depression and diabetes mellitus on the risk for dementia: a national population-based cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(6):612–619. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynolds CF., 3rd Promoting healthy brain aging. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(6):619–620. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liddy C, Blazkho V, Mill K. Challenges of self-management when living with multiple chronic conditions: systematic review of the qualitative literature. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(12):1123–1133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bratzke LC, Muehrer RJ, Kehl KA, Lee KS, Ward EC, Kwekkeboom KL. Self-management priority setting and decision-making in adults with multimorbidity: a narrative review of literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(3):744–755. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritter PL, Lee J, Lorig K. Moderators of chronic disease self-management programs: who benefits? Chron Illn. 2011;7(2):162–172. doi: 10.1177/1742395311399127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marks R, Allegrante JP, Lorig K. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: implications for health education practice (part II) Health Promot Pract. 2005;6(2):148–156. doi: 10.1177/1524839904266792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marks R, Allegrante JP, Lorig K. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: implications for health education practice (part I) Health Promot Pract. 2005;6(1):37–43. doi: 10.1177/1524839904266790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arora NK. Interacting with cancer patients: the significance of physicians’ communication behavior. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(5):791–806. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00449-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewin SA, Skea ZC, Entwistle V, Zwarenstein M, Dick J. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;4:CD003267. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE., Jr Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989;27(3 Suppl):S110–S127. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Epstein RM, Street RL. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff. 2010;29(8):1489–1495. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WESTAT. Health Information National trends survey 4 (HINTS 4): cylce 2 methodology report. Rockville, MD: Westat; 2013.

- 33.Arora NK, Hesse BW, Clauser SB. Walking in the shoes of patients, not just in their genes: a patient-centered approach to genomic medicine. Patient. 2015;8(3):239–245. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stockburger DW. Introductory statistics: concepts, models, and applications. 3. Springfield: Missouri David W. Stockburger; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bayliss EA, Balasubramianian BA, Gill JM, Stange KC. Perspectives in primary care: implementing patient-centered care coordination for individuals with multiple chronic medical conditions. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):500–503. doi: 10.1370/afm.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dietrich AJ, Oxman TE, Williams JW, Jr, Kroenke K, Schulberg HC, Bruce M, et al. Going to scale: re-engineering systems for primary care treatment of depression. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(4):301–304. doi: 10.1370/afm.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care—a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1064–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0706165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pham HH, Schrag D, O’Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(11):1130–1139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa063979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fahimi M, Link M, Mokdad A, Schwartz DA, Levy P. Tracking chronic disease and risk behavior prevalence as survey participation declines: statistics from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system and other national surveys. Prev Chron Dis. 2008;5(3):A80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV, Cynamon ML. Telephone coverage and health survey estimates: evaluating the need for concern about wireless substitution. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):926–931. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cantor D, Coa K, Crystal-Mansour S, Davis T, Dipko S, Sigman R. Health information national trends survey (HINTS) 2007. Rockville, MD: Westat; 2009.

- 42.Nelson DE, Powell-Griner E, Town M, Kovar MG. A comparison of national estimates from the National Health Interview Survey and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1335–1341. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.8.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gentry EM, Kalsbeek WD, Hogelin GC, Jones JT, Gaines KL, Forman MR, et al. The behavioral risk factor surveys: II. Design, methods, and estimates from combined state data. Am J Prev Med. 1985;1(6):9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.About CAHPS [cited May 26, 2016]. http://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/about-cahps/index.html. Accessed Jan 2016.

- 45.Epstein RMSRJ. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.