Abstract

Introduction: Although there is evidence that hexaminolevulinate (HAL)-based transurethral bladder tumor resection (TURBT) improves the detection of Ta-T1 non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) as well as carcinoma in situ there is uncertainty about its beneficial effects on progression.

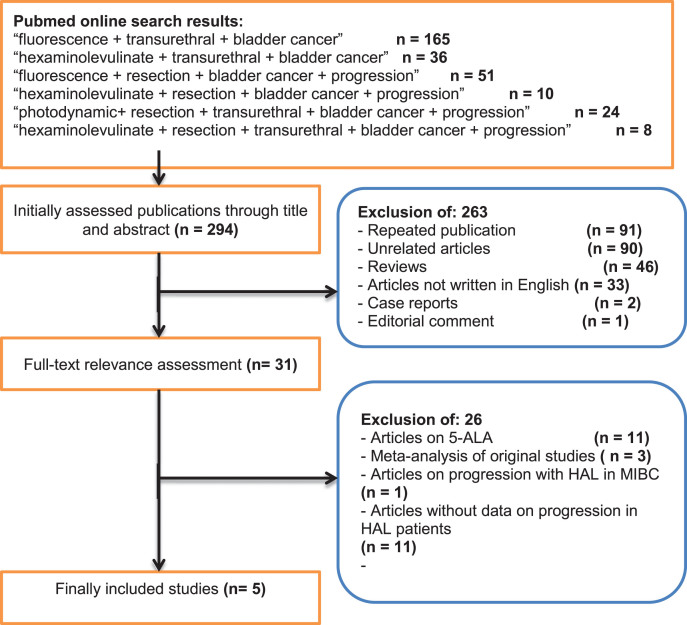

Material and Methods: A systematic literature search was conducted according to the PRISMA statement to identify studies reporting on HAL- vs. white-light (WL-) based TUR-BT in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer between 2000 and 2016. A two-stage selection process was utilized to determine eligible studies. Of a total of 294 studies, 5 (4 randomized and one retrospective) were considered for final analysis. The primary objective was the rate of progression.

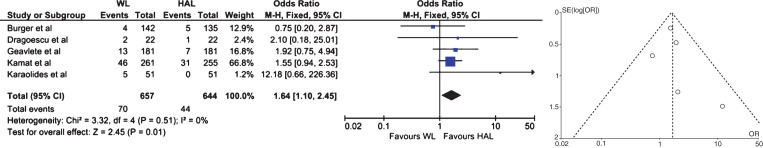

Results: The median follow-up for patients treated with HAL- and WL-TURBT was 27.6 (1–55.1) and 28.9 (1–53) months, respectively. Of a total of 1301 patients, 644 underwent HAL- and 657 WL-based TURBT. Progression was reported in 44 of 644 patients (6.8%) with HAL- and 70 of 657 patients (10.7%) with WL-TURBT, respectively (median odds ratio: 1.64, 1.10–2.45 for HAL vs. WL; p = 0.01). Data on progression-free survival was reported in a single study with a trend towards improved survival for patients treated with HAL-TURBT (p = 0.05).

Conclusions: In this meta-analysis the rate of progression was significantly lower in patients treated with HAL- vs. WL-based TURBT. These results support the initiation of randomized trials on HAL with progression as primary endpoint.

Keywords: Aminolevulinate, bladder cancer, fluorescence, hexaminolevulinate, photodynamic diagnosis, progression, and transurethral resection

INTRODUCTION

Hexaminolevulinic acid (HAL) is a hexyl ester of 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and has been approved for photodynamic diagnosis (PDD) of bladder tumors [1]. Following intravesical administration, HAL acts as precursor molecule which is taken up by urothelial cells and incorporated into heme biosynthesis resulting in intracellular accumulation of photoactive porphyrines especially within neoplastic urothelial cells [2]. When these enriched cells are exposed to blue light they emit red light of characteristic wavelength that can be visualized with the use of specific filters during transurethral bladder tumor resection (TUR-BT).

Based on the results of randomized trials HAL-based TUR-BT has been implemented into clinical practice as the standard for fluorescence-based TUR-BT [1]. In an updated meta-analysis of raw data, an increase in the detection rate of Ta-T1 lesions by 20% and carcinoma in situ (CIS) by 40% was reported [3].

Given the improved detectability of CIS with HAL [3], there is a rationale for hypothesizing that HAL-based TURBT may also impact on progression in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). Prior meta-analyses aimed to address possible effects of HAL-TURBT on progression but did not report on a beneficial impact. Taking a closer look on these meta-analyses it has to be assumed that their results could have been biased by the duration of follow-up and definition of progression of the included studies [4–6].

Given these possible limitations we aimed to systematically re-review the current body of evidence with regard to updated data reporting on the effects of HAL-based TUR-BT on progression in patients with NMIBC.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted according to the PRISMA statement [7] to identify studies reporting on progression after HAL- and WL-based TUR-BT for NMIBC between 2000 and 2016. The Pubmed database was searched along with a free-text hand search using one or several combinations of the following items: aminolevulinate, bladder cancer, fluorescence, hexaminolevulinate, photodynamic diagnosis, progression, and transurethral resection. The selection process was conducted at two stages; the first stage was performed via initial screening of the title and abstract to identify eligible publications. The second stage was done via full-text reading including a manual search of publications in journals not listed in PubMed to further avoid missing any eligible study. For this systematic review, we excluded (I) non-English articles, (II) non-original articles (i.e. review articles with or without systematic review or meta-analysis), (III) editorials or case reports (IV) studies on ALA-based TURBT and (V) repeated publications on the same cohort to avoid publication bias. After completion of the systematic search, a risk of bias assessment was conducted according to the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of randomized studies [8] and Newcastle-Ottawa scale for retrospective studies [9].

Data extraction

Data was initially extracted independently by both authors. Then double check was performed. The following variables were extracted: number of patients, early intravesical instillation, adjuvant treatment, duration of follow-up, follow-up strategy, modality of TURBT (HAL- vs. WL-) and rate of progression.

Outcome measures

The rate of progression was the primary objective of this study. Analysis of progression-free survival (PFS) was not conducted as only one study reported on data of PFS [10]. Progression was defined according to the definitions of the respective publications as outlined in Table 1. One study defined progression as stage T2 disease and another according to the criteria of the International Bladder Cancer Group (IBCG) [11]. Some studies did not explicity define progression in their publication.

Table 1.

Studies comparing progression rates in patients treated with HAL- vs. WL- TURBT (Leg: CYS: cystoscopy, CYT: urinary cytology, EAU GL: adjuvant therapy as indicated in the guidelines of the European Association of Urology; F/U: follow-up; HAL: hexaminolevulinate; IBCG: International Bladder Cancer Group; MMC: mitomycin-C; mo.: months; N.: number of patients; n.s.r: not separately reported; perf.: performed; q3m: every 3 months; q6m: every 6 months; RETRO: retrospective, RANDO: randomized; SCP: standard clinical practice; WL: white-light; yr: year)

| Author | Study | N | Median | Median | Follow-up | Early | Adjuvant | Definition of | Progression | Progression |

| design | F/U WL [mo.] | F/U [mo.] HAL | strategy | instillation | therapy | progression | WL (in %) | HAL (in %) | ||

| Burger et al. [11] | RETRO | 277 | 23 | 21 (1–36) | CYS+CYT q3 m for 2 yrs, q6 m thereafter | n.s.r. | EAU GL | stage T2 | 4/142 (2.8) | 5/135 (3.7) |

| Dragoescu et al. [12] | RANDO | 44 | n.s.r. | n.s.r. | CYS q3 m in 1styr | Perf. | EAU GL | n.s.r. | 2/22 (9.1) | 1/22 (4.6) |

| Geavlete et al. [13] | RANDO | 362 | n.s.r. | n.s.r. | CYS+CYT q3 m for 2yrs. | Perf. | EAU GL | n.s.r. | 13/181 (7) | 7/181 (4) |

| Kamat et al. [11] | RANDO | 516 | 53 | 55.1 | CYS after 3, 6 and 9 mo. | n.s.r. | BCG in T1/CIS+SCP | IBCG | 46/261 (17.6) | 31/255 (12.2) |

| Karaolides et al. [14] | RANDO | 102 | 14 | 17.5 | CYS at 3 mo., EAU GL | Perf. | EAU GL | n.s.r. | 5/51 (9.8) | 0/51 (0) |

| Total | 1301 | 28.9 | 27.6 | 70/657 (10.7) | 44/644 (6.8) |

Statistical analysis

Review Manager (RevMan) software version 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen) was utilized for this meta-analysis. Fixed and random effect models were used according to the n2 value of heterogeneity; for I2 ≤50%, a fixed effect model was applied, whereas for I2 >50% a random model was used. A p-value <0.05 was considered as level of significant difference.

RESULTS

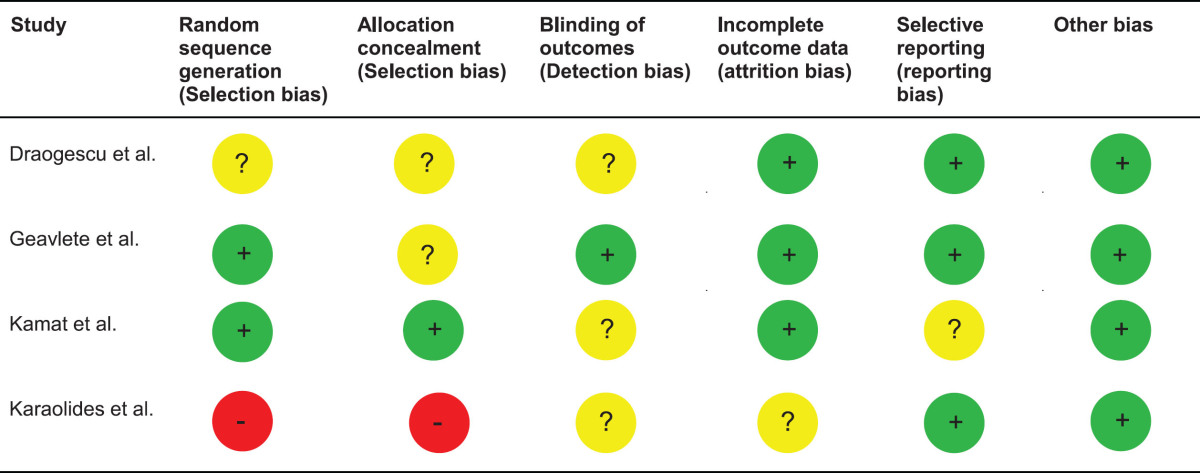

A CONSORT diagram for the selection process of included studies is provided in Fig. 1. The initial online search resulted in the identification of 294 publications out of which 263 were excluded after initial assessment. Of the 31 publications subjected to full text assessment, 26 were excluded after the second stage. Finally, 5 studies including 1301 patients were considered for final analysis [10, 12–15]. Of these, 4 were randomized trials [10, 13–15] and one a retrospective study [12]. Table 1 summarizes the basic data of the included studies. A risk of bias assessment for the included studies is given in Tables 2 and 3. Overall, the risk of bias was low to moderate for the majority of randomized studies and low for the one retrospective study.

Fig.1.

A CONSORT diagram which outlines the selection process of the included studies.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment according to the Cochrane methods of bias assessment for randomized studies included in this meta-analysis (Leg.: GREEN: low risk of bias; YELLOW: unclear risk of bias; RED: high risk of bias)

The median follow-up (total range) of patients treated with HAL- and WL-TURBT was 27.6 (1–55.1) and 28.9 (1–53) months, respectively. Of the 1301 patients, 644 underwent HAL-TURBT (49.5%) and 657 WL-based TURBT (50.5%). Progression was found in 44 of the 644 patients (6.8%) with HAL-TURBT and 70 of the 657 patients (10.7%) with WL-TURBT, respectively (median odds ratio: 1.64, 1.10–2.45 for HAL vs. WL; p = 0.01). Figure 2 provides the corresponding forest and funnel plots. Data on PFS was reported in a single study with a trend towards improved PFS for patients treated with HAL vs. WL-based TURBT (p = 0.05).

Fig.2.

Meta-analysis of the included studies with regard to progression as illustrated by forest and funnel plots (Leg.: ALA: 5-aminolevulinic acid; HAL: hexaminolevuinate; WL: white-light, CI: confidence interval).

DISCUSSION

In NMIBC, randomized studies have shown that HAL-TUR-BT facilitates the detection of tumor-suspicious areas in the bladder that might be overseen during conventional resection under WL [15]. In these trials, intravesical recurrence-free survival was used as primary endpoint and was proven to be significantly longer for patients treated with HAL-guided TURBT. Despite a significantly improved detection rate of CIS these studies could not confirm an impact of HAL-TUR-BT on progression [16]. One reason for this finding is that these studies were not adequately powered to either confirm or disprove an impact of HAL-TURBT on progression.

The results of this meta-analysis suggest for the first time that the performance of HAL-based TURBT confers a prognostic benefit to patients with NMIBC in terms of progression. Four of the five included studies were conducted as clinical trials [10, 13–15]. In these studies a total of 1024 patients were randomized to either HAL or WL-TURBT. This relates to 79% of the total number of included patients in this meta-analysis. To avoid any publication bias we only considered the most updated data on the same cohort [10, 17].

Generally, the definition of progression in NMIBC is crucial as it indicates worsening of the disease. However, until now, there is no unequivocal definition of progression [11]. In the study by Burger et al. progression was defined as stage T2 disease [12]. In three of the five included studies no definition of progression was provided in the respective full-text publications [13–15]. Of note, these three studies did not report on a beneficial impact of HAL-TURBT on progression. The largest and most recent publication re-analyzed the dataset of a phase III randomized trial on HAL vs. WL-TURBT with regard to progression [10] using a new definition provided by the International Bladder Cancer Group (IBCG) [11]. In detail, any increase in tumor grade from low to high or stage (from Ta to CIS/T1, CIS to T1, ≥T2 stage, or N+ or M+) is herein defined as progression. This definition takes several biological considerations on bladder cancer into account. Tumor cells that penetrate the basement membrane are capable of invading lymphatic and blood vessels and causing clinical progression [1]. Likewise, an increase in the tumor grade or presence of CIS clearly indicates a higher propensity of tumor cells to invade the submucosa [1]. On this occasion, it should be also noted that this definition does not comprehensively reflect urothelial carcinoma biology as, i.e. it does not consider worsening of the disease in patients with stage T1 NMIBC who exhibit lymphovascular invasion in the resection specimen during follow-up [18]. Notwithstanding, by using this new definition, progression was reported in 31 (12.2%) HAL-patients and 46 (17.6%) WL-patients (p = 0.085) [10]. By contrast, in the initial publication in which stage≥T2 disease was used for definition of progression, less patients (8 (3.1%) patients in the HAL- and 16 (6.3%) in the WL-group) were considered to have experienced progression [17]. Nonetheless, it has to be borne in mind that this new analysis did not provide an update on the follow-up of patients [10]. Thus, the observed differences in progression might have become even more pronounced with longer follow-up. While in all five studies the reported rates of progression were numerically lower for patients treated with HAL-guided TURBT, the median periods of follow-up differed extremely across studies ranging between 14 to 55 months [10, 12–15]. Of note, the largest study which randomized 516 patients to HAL and WL-TURBT reported on progression rates after a long-term follow-up of 53–55 months [10].

Taken the results of this meta-analysis, one may hypothesize that a delay of progression may also result in a prognostic benefit of those who would need to undergo radical surgery as curative treatment. Radical cystectomy (RC) represents the mainstay of treatment of muscle-invasive bladder cancer [5] or NMIBC at high risk of progression [19, 20]. Pathological tumor and nodal stage as well as the surgical margin status (STSMs) represent well-established histopathological risk factors for recurrence-free (RFS), cancer-specific (CSS) and overall survival (OS) [19]. Whether photodynamic diagnosis-based TUR-BT exerts any impact on the long-term oncological outcomes of patients with bladder cancer who will need to undergo RC during their course of disease remains elusive.

In this regard, a single-center series of 224 consecutive patients who were treated with RC with standard bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection for bladder cancer between 2002 and 2010 retrospectively investigated outcomes with regard to the modality of TURBT prior to RC (HAL vs. ALA vs. WL) [21]. After a median follow-up of 29 months, the median 3-year-RFS, CSS and OS survival rates were significantly longer for patients who underwent HAL-TURBT compared to WL or ALA-TURBT prior to RC. In multivariable analysis, histopathological tumor and nodal stage, soft-tissue margin status and the modality of TUR-BT (HAL vs. non-HAL) were independent predictors for RFS, CSS and OS. In conclusion, these results suggest that HAL-based TURBT may provide also a beneficial impact on survival even for those patients who will need to undergo RC during the course of their disease.

This meta-analysis has limitations which need to be taken into account in the interpretation of the results. First, we were not able to conduct a meta-analysis on PFS as only one study reported on hazard ratios [10]. The heterogeneous definition of progression and differences in duration of follow-up across studies may have impacted on our results. A selection bias might also exist for patients who were treated with WL-based TUR-BT only as they might have undergone a more intense follow-up by the treating urologist. However, based on the assessment of the risk of bias applied in this study the risk is rather low which supports our interpretation of the results. Differences in the utilization of adjuvant instillation regimens may have also influenced outcomes. Yet, in the largest study included in this meta-analysis, similar rates of intravesical instillation therapy were reported between both groups (45% for HAL, 46% for WL) [17]. Our meta-analysis differs from previous ones as follows: one study [16] which was included in the most recent meta-analysis by Lee et al. [4] reported on early data on progression with 5 and 7 patients progressing to T2 stage disease in the WL- and HAL-group, respectively. Yet, a trend towards an increased rate of “worrisome” cancers (Tis/T1) was noted in that study (p = 0.17). By contrast, an updated report from the same cohort published in 2012 reported on a longer follow-up period with 16 and 8 patients in the WL- and HAL group exhibiting muscle-invasive disease, respectively (p = 0.066).A recent update of the same study cohort reanalyzed outcomes based on a new definition of progression according to the IBCG criteria. A trend towards reduced risk of progression was noted (p = 0.085). The meta-analysis by Yuan et al. [6] included the same studies for analysis of progression as the study by Lee et al. [4]. In the meta-analysis by Shen et al. data on progression from HAL and ALA-studies were analyzed in one group [5]. Of the three publications which were considered for that meta-analysis two were exclusively based on ALA [22, 23].

In summary, this is the first meta-analysis which shows a significant beneficial impact of HAL-TURBT on progression in NMIBC. By contrast to recent recommendations for trial designs in NMIBC [24] the results of this study support the performance of randomized trials with progression as primary endpoint to improve our understanding of the therapeutic potential of HAL-guided TURBT in NMIBC.

CONCLUSIONS

This meta-analysis supports the assumption that the detection and resection of NMIBC with HAL-guided TURBT reduces the risk of progression. Therefore, patients should receive hexaminolevulinate- rather than white-light-guided TURBT at their first resection as this might allow more patients at risk of progression to be treated timely and adequately.

DISCLOSURES

Georgios Gakis: Receipt of speaker honoraria and travels grants by IPSEN GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany and Photocure, Oslo, Norway.

Table 3.

Risk of bias assessment according to the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the non-randomized study [9] included in this meta-analysis (Leg.: scores ≥7–9, 4–6, <4 are considered as low, intermediate, and high risk, respectively); *= 1 point

| Study | Selection | Comparability of cohorts | Outcome | Overall | |||||

| Representativeness | Selection of | Ascertainment | Outcome not | Assessment | Adequate follow-up | Adequacy of | |||

| of exposed cohort | nonexposed | of exposure | present at start | length | follow-up | ||||

| Burger et al. REF | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7/9 | |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

- [1]. Babjuk M, Bohle A, Burger M, Capoun O, Cohen D, Comperat EM, Hernandez V, Kaasinen E, Palou J, Roupret M, van Rhijn BW, Shariat SF, Soukup V, Sylvester RJ, Zigeuner R. EAU Guidelines on Non-Muscle-invasive Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder: Update 2016. European Urology 2016; doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Fotinos N, Campo MA, Popowycz F, Gurny R, Lange N. 5-Aminolevulinic acid derivatives in photomedicine: Characteristics, application and perspectives. Photochemistry and Photobiology 2006;82(4): 994–1015. doi: 10.1562/2006-02-03-IR-794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Burger M, Grossman HB, Droller M, Schmidbauer J, Hermann G, Dragoescu O, Ray E, Fradet Y, Karl A, Burgues JP, Witjes JA, Stenzl A, Jichlinski P, Jocham D. Photodynamic diagnosis of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer with hexaminolevulinate cystoscopy: A meta-analysis of detection and recurrence based on raw data. European Urology 2013;64(5):846–54. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.03.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Lee JY, Cho KS, Kang DH, Jung HD, Kwon JK, Oh CK, Ham WS, Choi YD. A network meta-analysis of therapeutic outcomes after new image technology-assisted transurethral resection for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: 5-aminolaevulinic acid fluorescence vs hexylaminolevulinate fluorescence vs narrow band imaging. BMC Cancer 2015;15:566 doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1571-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Shen P, Yang J, Wei W, Li Y, Li D, Zeng H, Wang J. Effects of fluorescent light-guided transurethral resection on non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU International 2012;110(6 Pt B):E209–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10892.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Yuan H, Qiu J, Liu L, Zheng S, Yang L, Liu Z, Pu C, Li J, Wei Q, Han P. Therapeutic outcome of fluorescence cystoscopy guided transurethral resection in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PloS One 2013;8(9):e74142 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, Group P-P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews 2015;4:1 doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Lundh A, Gotzsche PC. Recommendations by Cochrane Review Groups for assessment of the risk of bias in studies. BMC medical Research Methodology 2008;8:22 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Hartling L, Milne A, Hamm MP, Vandermeer B, Ansari M, Tsertsvadze A, Dryden DM. Testing the Newcastle Ottawa Scale showed low reliability between individual reviewers. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2013;66(9):982–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Kamat AM, Cookson M, Witjes JA, Stenzl A, Grossman HB. The impact of blue light cystoscopy with hexaminolevulinate (HAL) on progresion of bladder cancer - a new analysis. Bladder Cancer 2016; doi: 10.3233/BLC-160048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Lamm D, Persad R, Brausi M, Buckley R, Witjes JA, Palou J, Bohle A, Kamat AM, Colombel M, Soloway M. Defining progression in nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer: It is time for a new, standard definition. The Journal of Urology 2014;191(1):20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.07.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Burger M, Stief CG, Zaak D, Stenzl A, Wieland WF, Jocham D, Otto W, Denzinger S. Hexaminolevulinate is equal to 5-aminolevulinic acid concerning residual tumor and recurrence rate following photodynamic diagnostic assisted transurethral resection of bladder tumors. Urology 2009;74(6):1282–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Dragoescu O, Tomescu P, Panus A, Enache M, Maria C, Stoica L, Plesea IE. Photodynamic diagnosis of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer using hexaminolevulinic acid. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology=Revue Roumaine De Morphologie et Embryologie 2011;52(1):123–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Geavlete B, Multescu R, Georgescu D, Jecu M, Stanescu F, Geavlete P. Treatment changes and long-term recurrence rates after hexaminolevulinate (HAL) fluorescence cystoscopy: Does it really make a difference in patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC)? BJU International 2012;109(4):549–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10374.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Karaolides T, Skolarikos A, Bourdoumis A, Konandreas A, Mygdalis V, Thanos A, Deliveliotis C. Hexaminolevulinate-induced fluorescence versus white light during transurethral resection of noninvasive bladder tumor: Does it reduce recurrences? Urology 2012;80(2):354–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.03.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Stenzl A, Burger M, Fradet Y, Mynderse LA, Soloway MS, Witjes JA, Kriegmair M, Karl A, Shen Y, Grossman HB. Hexaminolevulinate guided fluorescence cystoscopy reduces recurrence in patients with nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. The Journal of Urology 2010;184(5):1907–13. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Grossman HB, Stenzl A, Fradet Y, Mynderse LA, Kriegmair M, Witjes JA, Soloway MS, Karl A, Burger M. Long-term decrease in bladder cancer recurrence with hexaminolevulinate enabled fluorescence cystoscopy. The Journal of Urology 2012;188(1):58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Gakis G, Todenhöfer T, Braun M, Fend F, Stenzl A, Perner S. Immunohistochemical assessment of lymphatic and blood vessel invasion in T1 urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Scandinavian Journal of Urology 2015;49(5):382–7. doi: 10.3109/21681805.2015.1040449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Gakis G, Efstathiou J, Lerner SP, Cookson MS, Keegan KA, Guru KA, Shipley WU, Heidenreich A, Schoenberg MP, Sagaloswky AI, Soloway MS, Stenzl A, International Consultation on Urologic Disease-European Association of Urology Consultation on Bladder C. ICUD-EAU International Consultation on Bladder Cancer Radical cystectomy and bladder preservation for muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. European Urology 2013;63(1):45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Witjes JA, Comperat E, Cowan NC, De Santis M, Gakis G, Lebret T, Ribal MJ, Van der Heijden AG, Sherif A, European Association of U. EAU guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: Summary of the guidelines. European Urology 2014;65(4):778–92. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Gakis G, Ngamsri T, Rausch S, Mischinger J, Todenhofer T, Schwentner C, Schmid MA, Hassan FA, Renninger M, Stenzl A. Fluorescence-guided bladder tumour resection: Impact on survival after radical cystectomy. World Journal of Urology 2015;33(10):1429–37. doi: 10.1007/s00345-015-1485-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Schumacher MC, Holmang S, Davidsson T, Friedrich B, Pedersen J, Wiklund NP. Transurethral resection of non-muscle-invasive bladder transitional cell cancers with or without 5-aminolevulinic Acid under visible and fluorescent light: Results of a prospective, randomised, multicentre study. European Urology 2010;57(2):293–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Stenzl A, Penkoff H, Dajc-Sommerer E, Zumbraegel A, Hoeltl L, Scholz M, Riedl C, Bugelnig J, Hobisch A, Burger M, Mikuz G, Pichlmeier U. Detection and clinical outcome of urinary bladder cancer with 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced fluorescence cystoscopy: A multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Cancer 2011;117(5):938–47. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Kamat AM, Sylvester RJ, Bohle A, Palou J, Lamm DL, Brausi M, Soloway M, Persad R, Buckley R, Colombel M, Witjes JA. Definitions, End Points, and Clinical Trial Designs for Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: Recommendations From the International Bladder Cancer Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2016;34(16):1935–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.4070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]