Abstract

More than 800 000 people die every year from suicide, and about 20 times more attempt suicide. In most countries, suicide risk is highest in older males, and risk of attempted suicide is highest in younger females. The higher lethal level of suicidal acts in males is explained by the preference for more lethal methods, as well as other factors. In the vast majority of cases, suicidal behavior occurs in the context of psychiatric disorders, depression being the most important one. Improving the treatment of depression, restricting access to lethal means, and avoiding the Werther effect (imitation suicide) are central aspects of suicide prevention programs. In several European regions, the four-level intervention concept of the European Alliance Against Depression (www.EAAD.net), simultaneously targeting depression and suicidal behavior, has been found to have preventive effects on suicidal behavior. It has already been implemented in more than 100 regions in Europe.

Keywords: antidepressant, depression, multifaceted intervention, suicide prevention

Abstract

Más de 800000 personas fallecen cada año por suicidio, y cerca de 20 veces más intentan suicidarse. En la mayoría de los países el riesgo suicida es más elevado en hombres de mayor edad y el riesgo de intento suicida es más alto en mujeres jóvenes. La mayor letalidad de los actos suicidas en los hombres se explica por la preferencia de métodos más letales como también por otros factores. En la gran mayoría de los casos, la conducta suicida ocurre en el contexto de los trastornos psiquiátricos, siendo la depresión uno de los más importantes. Aspectos centrales de los programas de prevención del suicidio lo constituyen la mejoría en el tratamiento de la depresión, la restricción en el acceso a medios letales y la evitación del efecto Werther (suicidio por imitación). En varias regiones europeas se ha encontrado que el concepto de intervención de cuarto nivel de la European Alliance Against Depression (www.EAAD.net), que se orienta simultáneamente a la depresión y la conducta suicida, tiene efectos preventivos en la conducta suicida. Esto ya ha sido implementado en más de 100 regiones de Europa.

Abstract

Plus de 800 000 personnes meurent chaque année par suicide et environ 20 fois plus tentent de se suicider. Dans la plupart des pays, le risque suicidaire est plus élevé chez les hommes âgés et le risque de tentative de suicide est plus élevé chez les femmes jeunes. Le taux de décès plus élevé des actes suicidaires chez les hommes s'explique par le choix de méthodes plus létales et par d'autres facteurs. Dans la grande majorité des cas, le comportement suicidaire survient dans le contexte de troubles psychiatriques dont la dépression représente le plus important. Les programmes de prévention du suicide sont axés sur l'amélioration du traitement de la dépression, la restriction de l'accès aux moyens létaux et la prévention de l'effet Werther (suicide mimétique). Dans plusieurs régions européennes, le concept d'intervention a quatre niveaux de l'European Alliance Against Depression (www.EAAD.net), ciblant simultanément la dépression et le comportement suicidaire, a montré des effets préventifs sur le comportement suicidaire. Il est déjà mis en oeuvre dans plus de 100 régions en Europe.

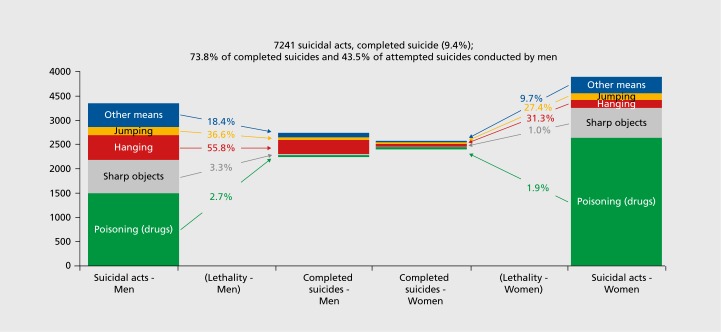

Epidemiology

According to analyses of the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 800 000 people died from suicide in 2012, and the number of attempted suicides is estimated to be about 20 times higher.1 Remarkable gender differences have been documented.1 The rate of attempted suicides is lower for males than females. However, the lethality of suicidal behavior is clearly higher in males, resulting in higher rates of completed suicides than in females.1 The male-female rate of age-adjusted suicide rates is especially high in Europe (about 4:1) and high-income countries, but is lower in low- and middle-income countries (1.6:1).1 A recent study with data from assessment regions of four different European countries confirmed the higher lethality of suicidal behavior in men (lethality of 13.9% vs 4.1%, Figure 1).2

Figure 1. Frequency of suicidal acts and suicides (data derived from OSPI-Europe intervention and control regions [2 or 3 years per country between 2008 and 2011 ]; see ref 2 for details of the study). OSPI-Europe, Optimizing Suicide Prevention Programs and their Implementation in Europe.

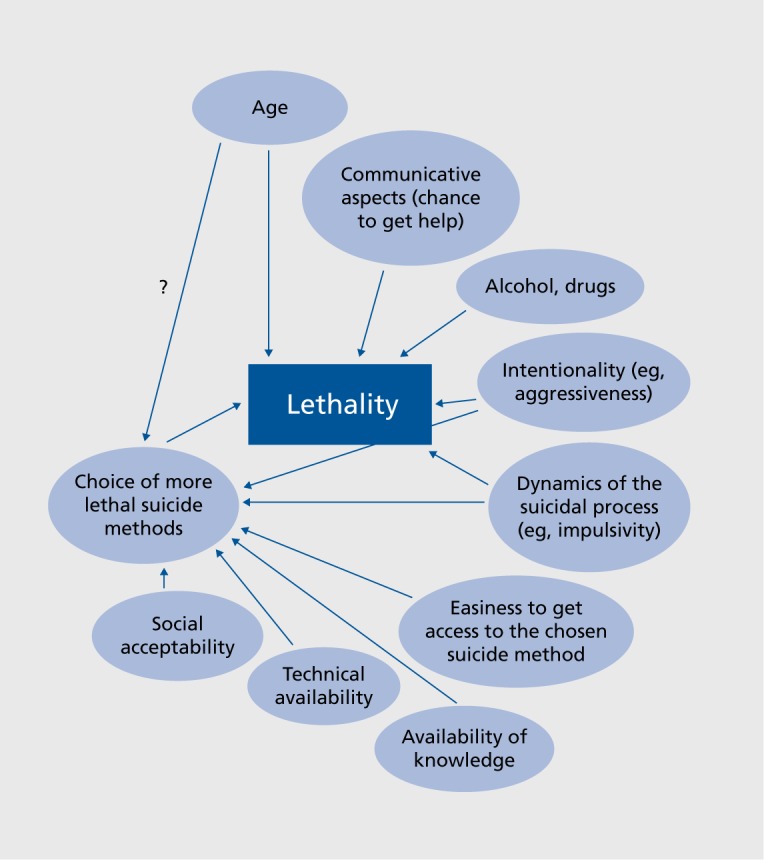

The main reason for this gender difference in lethality was the choice of more lethal methods by males.2 In addition, even within the same method, the outcome of suicidal acts was more lethal in males than in females, suggesting that there are gender differences for other aspects, such as intention to die or the social context in which the suicidal behavior is performed Figure 2.2 As can be seen in Figure 1, intoxication is by far the most often chosen suicidal method, and this is even more the case for females. In the aforementioned study, for females, 71% of all registered suicidal acts are due to intoxication, whereas in males, this is the case in only 50%. Because intoxication is so often used as a suicidal method, suicide rates depend on how lethal these intoxications are. In Europe, in more than 95% of cases, persons attempting these suicidal intoxications survived.2 However, in most low- and middle-income countries, pesticides and other toxic substances that are banned in Europe are available in many households.3 Consequently, many of the suicidal intoxications by females have a lethal outcome, explaining the more equal male-female rate of suicides. In China, suicide rates are even higher for females than for males due to a high frequency in young women in rural areas of suicide bypesticides or lethal poisons.1

Figure 2. Partly interacting factors contributing to lethality and gender differences in lethality of suicidal acts. Reproduced from ref 2: Mergl R, Koburger N, Heinrichs K, et al. What are reasons for the large gender differences in the lethality of suicidal acts? An epidemiological analysis in four European countries. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0129062. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution License.

With regard to completed suicides, hanging is overall the method used most frequently in Europe.3 In countries such as Switzerland or the United States where firearms are broadly available, they are the most often used method for completed suicides. In the United States, every day more than 100 people commit suicide, about 50% using firearms. Compared with other high-income countries, the rate of firearm suicides in the United States is 8 times higher, whereas the overall suicide rate is average.5 There is also evidence that the availability of firearms at home increases suicide risk.6 In most countries, suicide rates are low below the age of 15 and increase with age, especially in older age.1

Causes of suicidal behavior

Knowledge about the causes and determinants of suicidal behavior (defined here as attempted and completed suicides) is important in order to develop efficient suicide-prevention programs.

When discussing the causes for suicidal behavior in the context of depression or other psychiatric disorders, the patient's perspective has to be kept separate from the more objective medical perspective. From the patient's perspective, most suicidal patients feel they are in a life situation with unbearable suffering and without hope for relief. However, their perceptions of their life situations are often strongly distorted by psychiatric disorders. In the context of depression, existing private, professional, or health problems are magnified and become the main focus. The tinnitus or the lower back pain, for example, that has been tolerated well by the patient outside of the depressive episode becomes unbearable and will probably be reported as the reason for their hopelessness and suicidal thoughts. In schizophrenia, acoustic hallucinations or paranoid delusions can induce a high level of suffering, leading to suicidal behavior. It is therefore important to interpret the reasons for suicidal intentions provided by the patient in the context of possible distortions caused by psychiatric disorders. From an outside perspective, the reasons for suicidality provided by the patient are interpreted as a result of the psychiatric—eg, depressive or delusional—symptomatology. If depression is treated, then hope, energy, and the ability to experience pleasure will be regained, and all these problems, although objectively unchanged and possibly serious, will become manageable again, and part of the negative aspects of life. In order to put the patient's perspective in a more objective context, it is important that psychiatric disorders such as depression are carefully diagnosed. Disorders such as depression have to be taken as independent disorders and not as a mere consequence of difficult life circumstances.

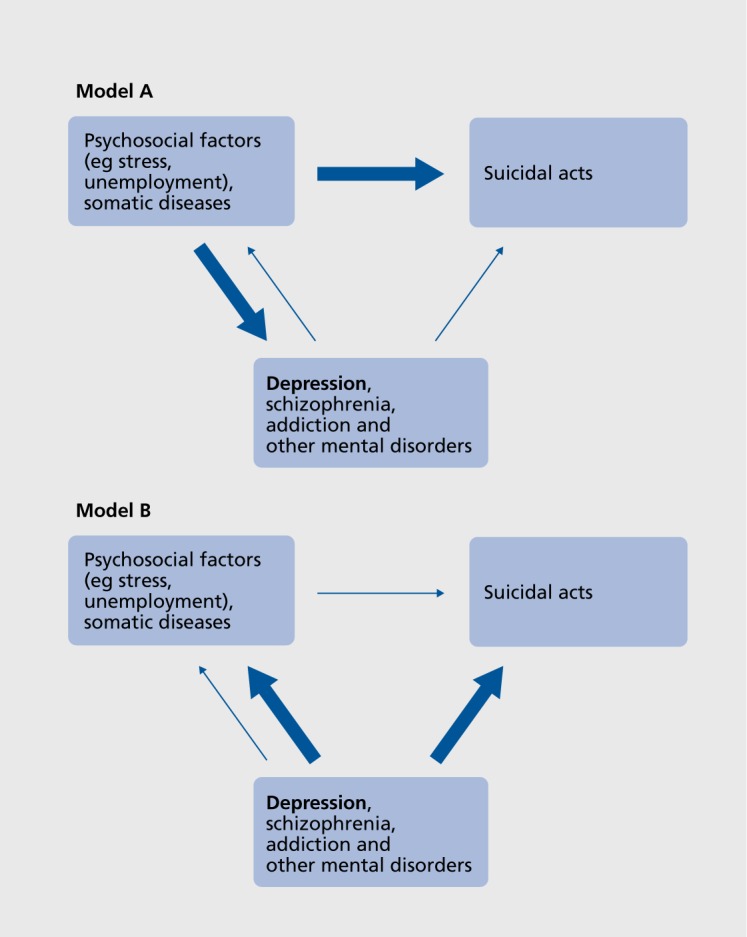

The two perspectives tend to lead to different prevention strategies. In Figure 3, two models concerning the causal links between depression and other mental disorders, psychosocial factors, and suicides are presented. Model A is often preferred by sociologists, health politicians, and lay people. It considers psychosocial circumstances—such as unemployment rate, social coherence at the societal level, or stressful life circumstances at the individual level—to be dominant causal factors leading both to mental disorders, such as depression, and to suicides. However, there are good arguments to assume that model B might be closer to the truth, as suggested, for example, by the following findings:

Figure 3. Two models concerning the causal relationships between depression and other mental disorders, psychosocial factors, and suicides. Model A is often preferred by sociologists and health politicians, as well as lay people; and Model B, by psychiatrists. Reproduced from ref 26: Hegerl U, Koburger N, Hug J. Depression and suicidality [in German], Nervenheilkunde. 2015;34(11):900-905. Copyright @ Schattauer, 2015.

Suicidal acts are rarely an act of free will, but are, in most cases, the tragic result of untreated psychiatric disorders. Psychological autopsy studies showed that around 90% of suicide victims in high-income countries had been suffering from psychiatric disorders.7,8 Most important in this context are affective disorders, which have been present in more than 50% of suicide victims.8,9 Alcohol and drug dependence, schizophrenia, and personality disorders are further mental illnesses that are often identified in suicide victims by psychological autopsy studies.10

There have been several publications claiming that the economic crisis has induced an increase in suicide rates (for example, see refs 11 and 12). However, the literature is far from being consistent.13 Furthermore, it has to be discussed by which mechanisms the economic crisis could influence suicide rates. According to model B, a plausible hypothesis would be that in some countries the economic crisis would cause deterioration in care for people with mental disorders. In countries in which patients have to pay for antidepressants or psychotherapy and where mental health services are shut down because of the economic crisis, care for patients with mental disorders would deteriorate and more patients would remain untreated. It can be expected that this would lead to an increase in suicide rates. This interpretation is supported by a recent publication by Ricardo Gusmao and the European Alliance Against Depression (EAAD)14: data from 29 European countries showed that changes in suicide rates were not related to gross domestic product (GDP), unemployment rate, or alcohol consumption, but to the prescription of antidepressants. An increase in the rate of prescription of antidepressants was associated with a decrease in suicide rates.

The suffering associated with severe somatic disorders is often seen as a factor possibly leading to suicidal behavior. There are several studies suggesting that this is the case (see ref 15, for example). However, such findings might be influenced by methodological bias. For example, the increase in somatic complaints often observed within depressive episodes could lead to a better recognition rate of somatic disorders, as they are then more likely reported, or depression could increase the incidence of some somatic disorders. Of special interest for this discussion is a large study from Great Britain, in which over a period of 8 years and in cooperation with nearly 600 primary care providers, the patient charts of over 4 million patients were collected.16 They contained 873 suicide cases, enabling the analysis of how many of these suicide victims had at least one out of a list of 11 severe somatic disorders (stroke, cancer, asthma, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertonus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, epilepsy, chronic lower back pain, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis). This was found to be the case for 38.7% of suicide victims. However, this was also the case for 37% of the 17 000 controls who were of comparable age and gender. The diagnosis of cancer was present in 3.4% of the suicide victims; however, this was also true for 3.2% of the controls. These disorders apparently have not increased the suicide risk, although it can be assumed that many of the patients had named the suffering and fears associated with these somatic diagnoses as reasons for their suicidal intentions. The objective perspective, however, shows that severe somatic disorders do not strongly increase the suicide risk. The presence or absence of depression or other mental disorders is more likely to be the crucial determinant.

After the reunification of Germany in the year 1990, a period of elevated social stress and societal change was experienced in the eastern part of Germany. The unemployment rate increased from zero to 20%, societal values were changed, and many professional careers came to a sudden end. According to the sociologist Emile Durkheim,17 this would be a classic scenario leading to increases in suicide rates. However, the opposite, namely a sharp decrease in suicide rates, was found in the eastern part of Germany.18 This can be considered as a nearly perfect disproving of Durkheim's theory.

These and further arguments support model B in Figure 3. According to this model, targeting undertreatment of depression and other psychiatric disorders plays a central role in the prevention of suicidal behavior.

Prevention of suicidal behavior and multilevel prevention programs

The amount of resources most countries invest in research and prevention of suicidal behavior is out of balance considering the size of the problem and the room for improvement in this field. It appears that decision makers are prone to invest more resources elsewhere, such as in preventing deaths by traffic accidents instead of deaths by suicide. What are the reasons for this? Sometimes there might simply be a lack of knowledge about the high numbers of suicidal acts and the possibilities to prevent them. However, more deeply rooted personal and societal beliefs, as well as myths about suicidal behavior, also play a role. An implicit concept often found is that suicides are acts of free will and that there might be understandable and real reasons for some people to commit suicide in difficult life circumstances. To prevent such acts is then considered to have a lower priority than to prevent deaths by traffic accidents or other causes. However, as argued above, suicides are rarely acts of free will, but are in most cases a consequence of mental disorders. It is therefore an important signal that the action plan for mental health developed by the WHO in 201219 calls all member states to increase efforts to improve mental health and to reduce suicide rates by 10% by the year 2020.

National suicide prevention programs have to address all levels of society, including, among others, legislation, public opinions and attitudes, the health care system, or the people affected by mental disorders.1 The interventions can aim to positively influence the reasons that cause people to engage in suicidal behavior (eg, reducing hopelessness and despair within a depressive episode), but can also target other factors influencing the number and lethality of suicidal behaviors, such as reducing access to lethal methods or unfavorable media reporting inducing the Werther effect (imitation suicide).20 An impressive recent example of the Werther effect arose with the railway suicide by the German national goalkeeper Robert Enke, who suffered from depression. This suicide was followed by intense media reporting, including the broadcast of the funeral in a soccer stadium. This reporting induced not only a sharp increase in railway suicides in the days following this intense reporting, but had long-term effects. In the 2 years after the suicide of Robert Enke, the mean daily number of railway suicides was 2.7 compared with 2.3 in the 2 years before this event.21 Furthermore, it could be shown that this effect was also spreading to some neighboring countries.22 To avoid or reduce this Werther effect20 is an important component in suicide prevention programs.

In the following, the focus will be on the community based four-level intervention model promoted by the EAAD (www.eaad.net). This is, worldwide, the most often implemented and best evaluated intervention concept simultaneously targeting depression and suicidal behavior.23 It was first evaluated within the model project Nuremberg Alliance Against Depression24 and has since been implemented in more than 100 regions in Europe.

During the 2-year intervention period in Nuremberg (500 000 inhabitants), intense activities were started simultaneously on the following four levels24:

(i) Cooperation with general practitioners (GPs). Training was offered, as well as informational material that could be handed out to patients with depression. This intervention level is justified in that most suicidal patients are seen by primary health care providers and that more expertise in providing care for suicidal and/or depressed patients according to treatment guidelines is required.

(ii) A professional public relation campaign with the key messages “depression can hit everybody,” “depression has many faces,” and “depression can be treated.” The information campaign comprised an opening ceremony in the city hall, a series of public events, posters, leaflets, and a cinema spot.

(iii) Training of community facilitators and gatekeepers, including teachers, priests, geriatric caregivers, journalists, pharmacists, and other professional groups that are potentially in contact with depressed individuals in their working routine. The intervention was quite intense: more than 2000 community facilitators were trained. With regard to the journalists, the focus was on increasing knowledge and sensibility concerning the risks of reporting about suicidal behavior in the media. Therefore, a media guide, together with background information, was given to journalists, providing recommendations for beneficial reporting in order to reduce the Werther effect.

(iv) Support of self-help by founding self-help groups and providing patients and relatives with information.

This 2-year-intervention was evaluated by investigating changes in the number of suicidal acts (completed + attempted suicides; primary outcome). This was done for the intervention region and 2-year intervention period compared with a 1-year baseline and corresponding changes in the control region (the city of Wuerzburg; 286 885 inhabitants). A 24% reduction in suicidal acts compared with the baseline was observed in Nuremberg, whereas no major changes were found in the control region.24 This effect turned out to be sustainable in the follow-up year.25 Further analysis showed that the effect was especially pronounced for serious suicide attempts conducted with more lethal methods.24 This finding was not unexpected, because the training of GPs, policemen, and other community facilitators probably increased their recognition rate for suicidal behavior. For example, it depends on the awareness of the family doctor who visits an older patient with an intoxication at home whether this is classified as a suicide attempt or not. Such a bias is less likely for more severe suicide attempts, which are more reliably detected.

These results triggered the interest of many other regions in Germany. Meanwhile, under the auspices of the German Depression Foundation, more than 75 regions and cities have started their own alliances against depression in Germany, building on the available intervention and evaluation materials and supported by a coordinating center.26

Because of the interest of regions from other European countries, the EAAD was founded.23 It was first started as a European Union (EU)-funded research project and is now continued as a nonprofit association that promotes implementation of this four-level intervention concept in and outside of Europe. This has led to a further improvement in and enrichment of the intervention materials, as best practice materials from different countries have been integrated into the intervention concept. Furthermore, with regard to completed suicides, the evaluation of the activities in Hungary supports the effectiveness of this intervention concept. In the intervention region Szolnok, a significant reduction in completed suicides was observed both compared with a control region and with changes in national suicide rates.27 In the meantime, the European Commission's Green Paper on mental health (http://ec.europa.eu/health/mental_health/policy/eu/green_paper/index_en.html) and the WHO'S recent suicide prevention report1 have listed the four-level intervention concept of the EAAD as a best practice example for suicide prevention and optimization of care for people with depression.

Recently, the intervention materials have been further complemented. In order to support self-help and to reduce the treatment gap in psychotherapy, the iFightDepression tool has been integrated. This Internet-based, guided self-management tool has been developed and consented to within the EU-funded project PREDI-NU (Preventing Depression and Improving Awareness through Networking in the EU; http://www.eaad.net/mainmenu/research/predi-nu/) and is based on the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy.28 Several such programs have become available in recent years and have been found to be equivalent to face-toface cognitive behavioral therapy.29

Many lessons have been learned by the EAAD consortium from the many regional alliances against depression that have become active in the last 15 years:

Implementation research performed within the European project “OSPI-Europe” (Optimizing Suicide Prevention Programs and their Implementation in Europe), aiming at a further implementation and evaluation of the four-level intervention concept (http://www.eaad.net/mainmenu/research/ospi/), revealed that being active simultaneously at four different levels develops strong synergistic and also catalytic effects.29 For example, the public relations campaign motivates people with depression to seek help from their GP; one's GP might then be motivated to improve his expertise in treating depression and thus participate in the training sessions. Furthermore, this public relations campaign might lower the threshold for GPs to confront patients who often have a somatic disease concept and present somatic complaints with a possible psychiatric diagnosis. A few examples for catalytic effects were identified by the process analysis performed within the OSPI-Europe project.30 One example is an improvement in the cooperation between different levels of care. Another is the offering of new mental health services because mental health and suicide prevention “got on the radar” of health politicians and the general public.

Depression and suicidal behavior are only partly overlapping phenomena, because there are other disorders and causes for suicidal behavior and because not all patients with depression have suicidal tendencies. However, it turned out to be a special strength of this four-level intervention concept that both depression and suicidal behavior are intervention targets. This offers the possibility to shift the focus between these two aims depending on the target group of specific interventions. When addressing the general public, the topic of depression is on center stage, with the topic of suicide being more in the background. The reason for that lies in the unknown risks inherent in public relations campaigns that mainly target suicide prevention. Reducing the stigma and the social threshold associated with suicidal behavior or increasing the cognitive availability of suicide and suicidal methods might have unwanted effects on suicide rates. The long-term increase in railway suicides after the intense media reporting about the suicide of the German national goal keeper Robert Enke in 200921 calls for caution. In addition, a public relation, campaign that primarily targets depression is likely to have a broader impact on the attention of the general public and the community facilitators, because of the high number of people directly or indirectly affected by depression. Such an impact cannot be achieved by only focusing on suicidal behavior.

Focusing the intervention on depression without broadening it to other mental disorders that are known to be related to suicidal behavior proved to be a favorable strategy. An evidence-based intervention needs clear and circumscribed definitions and targets. Mental disorder or stress reduction as intervention targets would be too broad. Mental disorders comprise a large number of completely different disorders with different epidemiology, causes, treatments, and prevention strategies. Furthermore, experience from many alliances against depression showed that positive effects of the depression campaign—for example, effects on stigma or help-seeking behavior—spread also to other psychiatric disorders. People with anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or other mental disorders also feel addressed and supported by the depression campaign.

Conclusion

In summary, evidence-based intervention concepts that simultaneously target suicidal behavior and depression are available. The EAAD offers regions and countries that are interested in starting similar regional campaigns an extensive catalog of intervention and evaluation materials, continuous support in the implementation process, and training involving a train-the-trainer concept. In addition, broad experience has been gained on how to extend the four-level intervention concept from a model region to a nationwide campaign. In countries with a well-established civil society, a strong bottom-up element is important in this context. The regions starting regional alliances against depression have to identify themselves with their local alliance and gain support from volunteers and local sponsors.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Dipl-Psych Nicole Koburger, Dr Elisabeth Kohls, Dr Roland Mergl, and Sabine Heitmann, MA for their assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosure: Within the last 36 months. Prof Hegerl served as an advisory board member for Lundbeck, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Servier, and Otsuka Pharma; a consultant for Bayer Pharma; and a speaker for BristolMyers Squibb, MEDICE Arzneimittel, Novartis, and Roche Pharma.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide: a Global Imperative. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mergl R., Koburger N., Heinrichs K., et al What are reasons for the large gender differences in the lethality of suicidal acts? An epidemiological analysis in four European countries. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0129062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Värnik A., Kölves K., van der Feltz-Cornelis CM., et al Suicide methods in Europe: a gender specific analysis of countries participating in the “European Alliance Against Depression”. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(6):545–551. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.065391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Law S., Liu P. Suicide in China: unique demographic patterns and relationship to depressive disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10(1):80–86. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grinshteyn E., Hemenway D. Violent death rates: the US compared with other high-income OECD countries, 2010. Am J Med. 2015;129(3):266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller M., Warren M., Hemenway D., Azrael D. Firearms and suicide in US cities. Inj Prev. 2015;21(e1):e116–119. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2013-040969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arsenault-Lapierre G., Kim C., Turecki G. Psychiatric diagnoses in 3275 suicides: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavanagh JT., Carson AJ., Sharpe M., Lawrie SM. Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2003;33(3):395–405. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lönnqvist J. Major psychiatric disorders in suicide and suicide attempts. In: Wasserman, D, Wasserman, C, eds. Oxford Textbook of Suicidology and Suicide Prevention: a Global Perspective. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009:275–286. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertolote JM., Fleischmann A., De Leo D., Wasserman D. Psychiatric diagnoses and suicide: revisiting the evidence. Crisis. 2004;25(4):147–155. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.25.4.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang SS., Stuckler D., Yip P., Gunnell D. Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: time trend study in 54 countries. BMJ. 2013;347:f5239. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordt C., Warnke I., Seifritz E., Kawohl W. Modelling suicide and unemployment: a longitudinal analysis covering 63 countries, 2000-11. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(3):239–245. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fountoulakis KN., Kawohl W., Theodorakis PN., et al Relationship of suicide rates to economic variables in Europe: 2000-2011. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(6):486–496. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gusmão R., Quintão S., McDaid D., et al Antidepressant utilization and suicide in Europe: an ecological multi-national study. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erlangsen A., Stenager E., Conwell Y. Physical diseases as predictors of suicide in older adults: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(9):1427–1439. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webb RT., Kontopantelis E., Doran T., Qin P., Creed F., Kapur N. Suicide risk in primary care patients with major physical diseases: a case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):256–264. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durkheim E. Le suicide. Étude de sociologie. Paris, France: Les Presses universitaires de France; 1897 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidtke A., Weinacker B., Stack S., Lester D. The impact of the reunification of Germany on the suicide rate. Arch Suicide Res. 1999;5(3):233–239. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Public Health Action for the Prevention of Suicide: a Framework. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; . 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips DP. Influence of suggestion on suicide: substantive and theoretical implications of Werther effect. Am Sociol Rev. 1974;39(3):340–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hegerl U., Koburger N., Rummel-Kluge C., Gravert C., Walden M., Mergl R. One followed by many? - Long-term effects of a celebrity suicide on the number of suicidal acts on the German railway net. J Affect Disord. 2013;146(1):39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koburger N., Mergl R., Rummel-Kluge C., et al Celebrity suicide on the railway network: can one case trigger international effects? J Affect Disord. 2015;185:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hegerl U., Rummel-Kluge C., Varnik A., Arensman E., Koburger N. Alliances against depression - a community based approach to target depression and to prevent suicidal behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(10 pt 1):2404–2409. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hegerl U., Althaus D., Schmidtke A., Niklewski G. The alliance against depression: 2-year evaluation of a community-based intervention to reduce suicidality. Psychol Med. 2006;36(9):1225–1233. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600780X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hegerl U., Mergl R., Havers I., et al Sustainable effects on suicidality were found for the Nuremberg alliance against depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;260(5):401–406. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0088-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hegerl U., Koburger N., Hug J. Depression and suicidality [in German]. Nervenheilkunde. 2015;34(11):900–905. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szekely A., Thege BK., Mergl R., et al How to decrease suicide rates in both genders? An effectiveness study of a community-based intervention (EAAD). PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e75081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arensman E., Koburger N., Larkin C., et al Depression awareness and self-management through the internet: protocol for an internationally standardized approach. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4(3):e99. doi: 10.2196/resprot.4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersson G., Cuijpers P., Carlbring P., Riper H., Hedman E. Guided Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):288–295. doi: 10.1002/wps.20151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris FM., Maxwell M., O'Connor RC., et al Developing social capital in implementing a complex intervention: a process evaluation of the early implementation of a suicide prevention intervention in four European countries. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:158. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]