Abstract

Thrombocytopenia (T), anasarca (A), myelofibrosis (F), renal dysfunction (R), and organomegaly (O) (TAFRO) syndrome is a variant of multicentric Castleman's disease. We describe here a 57‐year‐old man who presented with persistent fever, pleural effusion, and ascites. He was negative for human immunodeficiency virus and human herpes virus‐8. A computed tomography scan showed an anterior mediastinal mass and small inguinal lymphadenopathy. Although a biopsy of the anterior mediastinum showed fatty tissue infiltrated with CD20 + and CD45RO + lymphocytes, a biopsy of the left inguinal lymph node revealed a hyaline vascular type of Castleman's disease. He subsequently developed severe thrombocytopenia and renal dysfunction. In addition, his bone marrow biopsy showed myelofibrosis. TAFRO syndrome was diagnosed based on the lymph node pathology and the characteristic manifestations of the syndrome. Tocilizumab and glucocorticoid therapy achieved complete remission and regression of the mediastinal mass. To our knowledge, this is the first report of TAFRO syndrome accompanied by an anterior mediastinal mass, which responded very well to therapy.

Keywords: Anterior mediastinal mass, multicentric Castleman's disease, TAFRO syndrome, tocilizumab

Introduction

Castleman's disease (CD), first reported in 1956, is a rare non‐neoplastic lymphoproliferative disorder 1. Multicentric CD (MCD) was recognized as a distinct subtype presenting multiple lesions and systemic symptoms. Recently, a variant of MCD without human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or human herpes virus‐8 (HHV‐8) infection was identified in Japan and named thrombocytopenia (T), anasarca (A), myelofibrosis (F), renal dysfunction (R), and organomegaly (O) 2 (TAFRO) syndrome. However, the aetiology of this syndrome remains unknown, and remission has been reported in only a few cases. Here, we report a case of TAFRO syndrome accompanied by an anterior mediastinal mass, which showed complete regression following glucocorticoid and anti‐interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) therapy.

Case Report

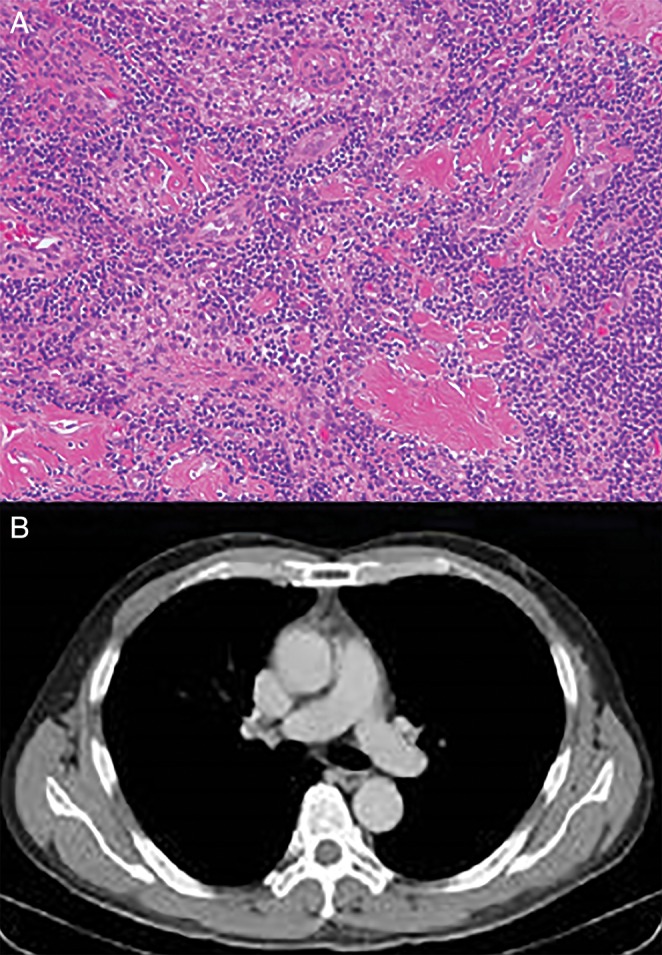

A 57‐year‐old man was admitted with persistent fever lasting one month, progressive exertional dyspnoea, abdominal distension, and bilateral leg oedema. He had been in good health until one month before admission. Prior to admission, he had been working as an office clerk, and he had begun smoking 25 years ago. His chest X‐ray showed bilateral pleural fluid. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed an anterior mediastinal mass (Fig. 1A), massive bilateral pleural fluid, and ascites. The positron emission tomography (PET) with 2‐deoxy‐2‐fluoro‐d‐glucose (FDG) revealed moderate FDG uptake equivalent to the maximum standard uptake value (SUV max) of 3.2 in the anterior mediastinal mass (Fig. 1B). His laboratory findings showed thrombocytopenia, elevated C‐reactive protein, elevated interleukin (IL)‐6 (14.8 pg/mL; standard range is below 4.0 pg/mL), hypoalbuminemia, and proteinuria. He was negative for HIV and plasma HHV‐8 DNA. We considered thymic carcinoma and Hodgkins’ lymphoma as the chief differential diagnoses. Aspirated ascites and pleural effusion were exudative and showed a lymphocyte‐dominant pattern but no malignancy. The culture results were negative for any pathogens, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Video‐assisted thoracoscopic surgery was performed to obtain a biopsy specimen of the anterior mediastinal mass. The mediastinal specimen disclosed mainly fatty tissue infiltrated with a small number of CD20+ and CD45RO+ lymphocytes, which suggested a lymphoproliferative disease. However, this finding was insufficient for a definitive diagnosis. We additionally performed a biopsy of the small left inguinal lymph node. During the diagnostic procedure, the patient presented a persistent high fever. His renal function gradually deteriorated, and he developed severe transfusion‐dependent thrombocytopenia (below 1.0 × 104/μL). A bone marrow biopsy showed sporadic myelofibrosis and abundant megakalyocytes. Finally, the pathology of the inguinal lymph node confirmed a hyaline vascular type of CD (Fig. 2A). We diagnosed TAFRO syndrome based on the typical clinical presentations and the pathological finding of inguinal node, which was compatible with hyaline vascular‐type CD. We started to administer glucocorticoid. After three weeks of continued glucocorticoid administration, only the persistent fever improved, whereas the severe thrombocytopenia and generalized oedema did not. Therefore, based on the slightly elevated serum IL‐6 level, we added a humanized anti‐human IL‐6 receptor antibody (tocilizumab) to the treatment regimen. As a result, his clinical symptoms and laboratory findings gradually improved over two months. His CT scan after complete remission revealed regression of the anterior mediastinal mass and disappearance of the pleural fluid and ascites (Fig. 2B). All other symptoms stemming from TAFRO syndrome resolved within three months of initiation of the therapy. Tocilizumab was continued up to eight months and stopped. Glucocorticoid was tapered and stopped after six months. He has experienced no relapse and has been without treatment for six months.

Figure 1.

(A) A computed tomography scan on admission showing anterior mediastinal mass enhanced with contrast medium. (B) Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan showing maximum standard uptake value of 3.2 in the anterior mediastinal mass lesion.

Figure 2.

(A) Histology of the left inguinal node showing hyaline vascular type of Castleman's disease. (B) A computed tomography scan taken after glucocorticoid and anti‐interleukin‐6 therapy showing complete resolution of the anterior mediastinal mass.

Discussion

The anterior mediastinal mass was found to be a manifestation of TAFRO syndrome because the mass clearly resolved after the anti‐inflammatory glucocorticoid and IL‐6 blockade therapy were administered. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an anterior mediastinal mass in TAFRO syndrome. In addition, we successfully achieved a completed remission of all the clinical presentations of TAFRO syndrome using only tocilizumab and glucocorticoids.

The biopsy specimen of the anterior mediastinal mass was insufficient to confirm the diagnosis in this case. However, the CD20+ B‐lymphocyte infiltration in the tissue strongly suggested a lymphoproliferative disease. Although we could not find any report regarding an anterior mediastinal mass in TAFRO syndrome, it is reportedly a common type of lesion in hyaline vascular‐type unicentric CD, which represents localized CD without systemic symptoms 3. Therefore, it is possible for TAFRO syndrome with hyaline vascular‐type CD to present a lymphoproliferative lesion in the anterior mediastinum. In addition, the patient's response to glucocorticoid and tocilizumab therapy supported our hypothesis that an anterior mediastinal mass can be connected to TAFRO syndrome.

Recently, IL‐6 blockade therapy has emerged as a treatment option for idiopathic MCD, which is MCD without HIV or HHV‐8 infection 4. Because TAFRO syndrome is regarded as a variant of idiopathic MCD, it is also treated with IL‐6 receptor monoclonal antibodies such as tocilizumab. However, some cases were refractory to glucocorticoid and anti‐IL‐6 therapy, requiring cytotoxic chemotherapy combined with anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab) or immunosuppressive agents 5. At the moment, the mechanism underlying the variability of the anti‐IL‐6 therapy response in TAFRO syndrome remains unknown.

In conclusion, our case suggested that the anterior mediastinal mass is a possible manifestation of TAFRO syndrome. Glucocorticoid and anti‐IL‐6 therapy can be effective for anterior mediastinal mass resolution in TAFRO syndrome.

Disclosure Statement

No conflict of interest declared.

Appropriate written informed consent was obtained for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tetsuya Obara and Dr. Ryohei Higuchi for the surgical biopsies. We also thank Dr. Takahiro Kiryu for the pathological diagnosis.

Sakashita, K. , Murata, K. , Inagaki, Y. , Oota, S. and Takamori, M. (2016) An anterior mediastinal lesion in TAFRO syndrome showing complete remission after glucocorticoid and tocilizumab therapy. Respirology Case Reports, 4 (5), e00173. doi: 10.1002/rcr2.173.

References

- 1. Castleman B, Iverson L, and Menendez VP. 1956. Localized mediastinal lymphnode hyperplasia resembling thymoma. Cancer 9(4):822–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kawabata H, Takai K, Kojima M, et al. 2013. Castleman‐Kojima disease (TAFRO syndrome): a novel systemic inflammatory disease characterized by a constellation of symptoms, namely, thrombocytopenia, ascites (anasarca), microcytic anemia, myelofibrosis, renal dysfunction, and organomegaly—a status. J. Clin. Exp. Hematop. 53(1):57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shahidi H, Myers JL, Kvale PA. 1995. Castleman's disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 70(10):969–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fajgenbaum DC, Van Rhee F, and Nabel CS. 2014. HHV‐8‐negative, idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease: novel insights into biology, pathogenesis, and therapy. Blood 123(19):2924–2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tedesco S, Postacchini L, Manfredi L, et al. 2015. Successful treatment of a Caucasian case of multifocal Castleman's disease with TAFRO syndrome with a pathophysiology targeted therapy—a case report. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 4(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]