Abstract

Background and Rationale:

Patients suffering with head and neck cancers are observed to have a relatively high risk of developing emotional disturbances after diagnosis and treatment. These emotional concerns can be best understood and explored through the method of content analysis or qualitative data. Though a number of qualitative studies have been conducted in the last few years in the field of psychosocial oncology, none have looked at the emotions experienced and the coping by head and neck cancer patients.

Materials and Methods:

Seventy-five new cases of postsurgery patients of head and neck cancers were qualitatively interviewed regarding the emotions experienced and coping strategies after diagnosis.

Results:

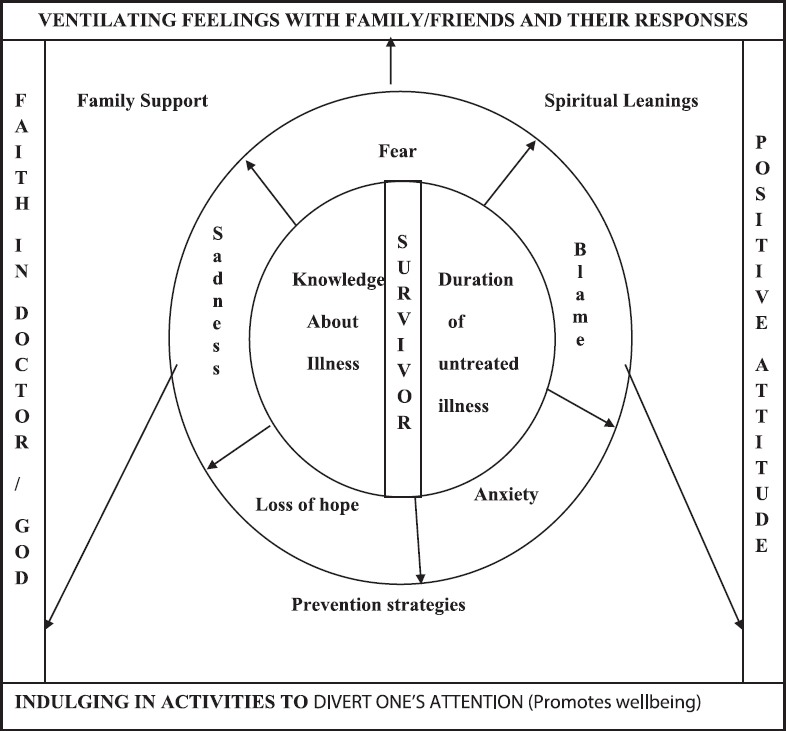

Qualitative content analysis of the in-depth interviews brought out that patients experienced varied emotions on realizing that they were suffering from cancer, the cause of which could be mainly attributed to three themes: 1) knowledge of their illness; 2) duration of untreated illness; and 3) object of blame. They coped with their emotions by either: 1) inculcating a positive attitude and faith in the doctor/treatment, 2) ventilating their emotions with family and friends, or 3) indulging in activities to divert attention.

Conclusion:

The results brought out a conceptual framework, which showed that an in-depth understanding of the emotions — Their root cause, coping strategies, and spiritual and cultural orientations of the cancer survivor — Is essential to develop any effective intervention program in India.

KEY WORDS: Cancer, coping, emotions

Background and Rationale

Anxiety and depression have strong and independent associations with the mental health domain in cancer patients.[1] Studies depict that cancer patients with a low level of optimism and a high level of pessimism are at risk of higher levels of anxiety and depression in addition to lowered health-related quality of life.[2] Further, anxiety, lack of positive support, detrimental interactions, threat of cancer, disease stage, age, and gender are observed to significantly predict the patient's mental health and survival.[3,4] Patients in an interpersonal/love/familial relationship during cancer were most satisfied with support, and experienced the highest self-esteem and mental health;[5] however, cancer patients who were unemployed, economically disadvantaged, or living alone were at risk for mood and mental health difficulties.[6,7] A number of qualitative studies in the last few years have also discussed specific mental health issues, emotions and coping of cancer patients.[8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]

Religion is seen to help cancer patients to cope better (in terms of support, hope, and meaning) with their disease.[20] Findings suggest that facets of spirituality (the ability to find meaning and peace in life) are an influential contributor to favorable adjustment during cancer.[21] Qualitative studies have shown that consistency and individuality characterized the role of religion and spirituality in cancer survivorship across themes such as impact of cancer on religion/spirituality, meaning-making, prayer, religious/spiritual role of others, and facing death.[13] In India, apart from other traditional methods (taking medications, indulging in exercise and activities to divert one's attention), spiritual methods of coping (prayer and meditation, adopting a positive attitude) were the most frequently used mainstream coping strategy by the patients suffering from head and neck cancers.[22]

Patients suffering from head and neck cancers are observed to have a relatively high risk of developing emotional disturbances after diagnosis and treatment.[23] These emotional concerns can be best understood and explored through the method of content analysis or qualitative data. Though a number of qualitative studies have been conducted in the last few years in the field of psychosocial oncology, none have looked at the emotions experienced and the coping of head and neck cancer patients. Further, the researchers believed that it would be interesting to understand the psychosocial oncology-related issues (such as the emotions and coping of patients) in the context of a developing and spiritual-oriented country such as India. Hence, this study was undertaken.

Materials and Methods

This study is part of a larger main study titled “Life after Cancer: A Psychosocial Impact,” which used a mixed methodology: A quantitative and qualitative paradigm.

Sample

A total of 75 head and neck cancer patients from the Tata Memorial Hospital (TMH), a tertiary care hospital for cancer care in Mumbai, Maharashtra, India were studied. As a majority of the head and neck cancers are squamous cell carcinomas (tumors that develop in the tissue lining the hollow of the body organs), consecutive patients suffering from squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity, hypopharynx, oropharynx, and larynx who were within the first 15 days post surgery were selected (the institute sees on an average 4000 cases per year). Only new patients (no relapse cases) in the age group of 30-60 years, with a minimum of 2 months of symptomatic phase (before surgery), who could speak English or Hindi were included in the study. The sociodemographic data of the patients who participated in the study were compiled [Table 1].

Table 1.

Socio-demographic data of patients (N = 75)

| Variable | N (%)/Mean (SD)* | Variable | N (%)/Mean (SD)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 48.3 (8.4)* | Education (in years) | 8.6 (6.0)* |

| Gender: | Family Type: | ||

| Male | 64 (85.3) | Nuclear | 52 (69.3) |

| Female | 11 (14.7) | Joint | 23 (30.7) |

| Occupation: | Comorbid medical illness: | ||

| Unemployed | 2 (2.7) | ||

| Daily wage | 34 (45.3) | Nil | 54 (72.0) |

| Professional | 22 (29.3) | Diabetes | 5 (6.7) |

| Housewife | 8 (10.7) | Hypertension | 12 (16.0) |

| Business | 9 (12.0) | Others | 4 (5.3) |

| Income (monthly): | Type of Cancer: | ||

| Low (BPL#) | 31 (41.3) | Ca Oral cavity | 58 (77.3) |

| Middle | 43 (57.3) | Ca Oropharynx | 3 (4.0) |

| High@ | 1 (1.4) | Ca Hypopharynx | 3 (4.0) |

| Ca Larynx | 11 (14.7) | ||

| Treatment given: | Stage of Cancer: | ||

| Only surgery | 62 (82.7) | Stage III | 42 (56.0) |

| Surgery+Chemotherapy | 13 (17.3) | Stage IV | 33 (44.0) |

| Surgery+Radiotherapy | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Duration of untreated illness (in months) | 7.4 (10.5)* | Family history of cancer (Yes) | 4 (5.3) |

*Mean (SD); #BPL: Below Poverty Line earning less than Rs 1700/- per month;[34] @Income greater than Rs 15,000 per month, taxable by the Government of India

Interview schedule

An interview schedule was formulated based on the aim of the study, literature review, and discussion with two experts in the field. It aimed to elicit the emotions experienced by the patients after hearing their diagnosis of cancer and the coping strategies used by them to deal with these emotions (the interview schedule is available from the authors on request). The interview schedule was written in two languages, English and Hindi, for the convenience of administration and the Hindi version was back-translated into English to check for concurrent validity. Patients who were unable to speak (some postoperative patients with cancer of the larynx; n = 11) were asked to write down their responses on a sheet of paper.

Procedure and ethics

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the erstwhile Department of Medical and Psychiatric Social Work and the Institute Ethics Committee at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. Written informed consent of the patients to participate in the study was obtained. The entire data collection procedure took a period of 6 months. The researcher met the participants in their wards and conducted in-depth interviews with the help of the interview schedule. The time spent in conducting the interview ranged 0.5-2 h depending on the capacity of the patient to speak after surgery. The researcher took down verbatim notes of the patients’ responses (written transcription) in a separate response sheet. The patients were slow in their communication and could speak only a few words (due to surgery); thus the data generated were not enormous and the researcher was able to complete the recordings efficiently. A majority of the patients (those who found it difficult to speak after surgery) used gestures and facial expressions to communicate information. The nonverbal data could not have been captured if audio recording was used. The nonverbal cues were responses to specific questions asked by the interviewer. If the interviewer did not understand the interpretation of these cues, she clarified the interpretation of the same with the respondent during the interview itself, by asking the respondent to write his/her responses or by clarifying what he/she was saying with the family members. Thus, only the interpretation of the nonverbal cues that were approved by the respondent was documented as part of the data collection. Reflexivity was exercised as the questions asked were fixed and structured as per the interview schedule. Therefore, the use of interview schedules did not offer much scope to the interviewer to include reflexivity in the analysis or bring in her reflections. The data thus collected were scrutinized by the second author (the supervisor of the interviewer) after each interview (especially in the pilot study) to correct any biases observed during the interviewing process. This was further corroborated by the information collected using the quantitative paradigm. While the information pertained to coping with the side effects of medication and cancer pain, part of this information was triangulated with the qualitative data. This corroboration added to the validity of the study.

Data analysis

A content analysis of each transcribed interview schedule was conducted. As the data generated were not extensive [as patients were slow in their communication and could speak only a few words (due to surgery)], only a manual thematic analysis was possible. The researcher then made a list of the common themes and subthemes across all interviews. A conceptual framework of the emotions experienced by the patients and the coping strategies employed by them were developed.

The data collected were divided into two main parts:

Emotions experienced by the patients after the diagnosis of cancer and

Coping strategies employed by the patients to deal with their emotions. Each part generated several themes and subthemes, which were substantiated adequately by patient quotations.

Results

Emotions experienced by the patients

The patients experienced varied emotions on realizing that they were suffering from cancer, the cause of which could be mainly attributed to three themes:

Knowledge/discovery of their illness;

Duration of untreated illness, and

-

Object of blame.

-

Emotions arising from knowledge/discovery of their illness: The most important theme which kept repeating across all interviews was the emotions experienced as a result of the patient's knowledge of his/her illnesses. The immediate reaction after becoming aware of their illness was often one of sadness:“I felt very sad, upset, and scared when I was told that I had cancer.” (47-year-old Mr. C.)“I often still cry when I think that I have cancer.” (51-year-old M.)Some patients were fearful or anxious about:

- Uncertainty in the future,

- Death,

- Costs of treatment, and

- Operative procedures when they heard about their diagnosis.

“I thought I could never be cured, would suffer all through my life, and die.” (50-year-old Mrs. F.)“I felt very tense and anxious when I was told about my diagnosis, as I did not know what lay in the future. My BP went up immediately.” (48-year-old Mr. RG.)“Bad thoughts came into my head. I thought something will happen to me; I believed it was life-threatening". (39-year-old Mr. SKS.)“I was scared when I heard that I was diagnosed with cancer, as I have seen my mother die due to this disease."(59-year-old Mr. T.)“I was scared that I had to get operated. I have still not been told the details of my illness.” (50-year-old Mrs. N.)“I was scared when I heard that I had a diagnosis of cancer, more because of the costs of treatment. I was not sure if I could afford the costs of the treatment and get well.” (60-year-old Mr. DP.)Some patients did not get mentally affected or emotionally disturbed about their diagnosis of cancer as the details of the illness were not disclosed to them by their doctor or family member. Others, who knew about their diagnosis, were fearful of disclosing the same to their family members:“I still do not know about the seriousness of the illness of cancer. My family seemed scared and they cried a lot. My daughter however, knew everything about the illness.” (55-year-old Mrs. M.)“I do not know anything about my illness. I believe my doctor will cure me and I will follow his instructions/treatment.” (48-year-old Mrs. P.)“I was worried when I was told about my diagnosis of cancer. I did not know how to break the news to my family. Only recently, the diagnosis was revealed to my wife.” (46-year-old Mr. S.)Those people who decided to mentally fight the illness felt that they could recover.“I never felt bad when I was told that I was diagnosed with cancer. I always believed that I could recover.” (50-year-old Mrs. A.“Everyone has to die one day. So when they told me I had cancer, I did not worry too much. My astrologer has told me that I will live a long life. So I was sure this illness will not affect me.” (52-year-old Mr. M.)“I have been very positive about my treatment, from the day I was diagnosed with cancer. I could freely talk about my illness to everyone in the ward and discuss with them the causes and treatment options.” (57-year-old Mr. O.)Emotional reactions and response on discovery or being told about the diagnosis of cancer varied from sadness, anxiety, fear of death and the inevitable, uncertainty about the future, and being disturbed. Collusion as strategy was observed when people chose not to divulge the diagnosis to their family members or their loved ones. Further, those who withheld the diagnosis for some time ultimately decided to disclose the information to their family members. While the disclosure of the diagnosis affected some participants, it also strengthened the resolve of others who had buffer support of the family, and faith in God and in their treating doctor. -

Emotions associated with the duration of untreated illness: Another theme that was prominently connected to the emotions of the patients was the “duration of untreated illness.” This theme was defined in the study as the time from the disclosure of the diagnosis till the time the patient was surgically operated for cancer. It was observed that longer the duration of the illness, more were the negative emotions experienced by the patients such as anxiety, sadness, and loss of hope. The duration of untreated illness was prolonged either due to the:

- Poor and slow response of the patient to other treatments (chemotherapy or radiation),

- Inability of the patient to afford the treatment/operation,

- Postponement of the date of surgery,

- the patient's fear of undergoing the operation.

“The treatment process is taking too long because of which I often get disillusioned and lose hope that I will ever get well soon.” (47-year-old Mr. NA.)“Because I was experiencing increasing pain by the day, I was upset that the treatment was not done earlier.” (54-year-old Mrs. US.)“The operation was stalled for 4 months as I did not have the money to pay for the treatment. Once I was able to get the money, I got admitted to the hospital and was operated.” (50-year-old Mr. V.)“I felt very anxious because of the prolonged length of the treatment. The further the date of my surgery got postponed, the more I was unsure that I would survive till then.” (55-year-old Mr. M.)“I was very anxious due to the long duration of treatment. I often wanted the treatment to end fast so that I could go home to my family.” (50-year-old, Mrs. F.)“I delayed the treatment by 1 month, as I did not want to get operated. I tried convincing the doctor to opt for treatments other than surgery as I was scared that my face will get disfigured". (38-year-old Mr. SS.)Some patients were anxious to complete their treatment as they were eager to get back to their routine lives with their families, start work, and resume their responsibilities:“I was anxious to complete treatment early so that I could go home and take care of my responsibilities and the family.” (54-year-old Mrs. D.)“I am dependent on my son for the costs of treatment and hospital stay. Due to the long duration of the treatment and increasing costs, my son is often upset with me and this makes me feel sad. I want to get well fast so that I can go home, work as before, and earn my living.” (55-year-old Mr. MM.)Very few patients stated that timely treatment was sought and provided:“I started treatment very early, immediately after my first symptoms were noticed. Hence, I have been very lucky and I am happy with my current condition.” (60-year-old Mr. D.) -

Emotions associated with the object of blame: A third theme that was connected to the patients’ emotions was their “object of blame,” which was expressed as anger toward their fate for their current illness.“My fate has played a role and has brought me here to this hospital with this diagnosis of cancer…” (59-year-old Mr. R.)“I believe I have got this illness because of my past karma — Past life's bad deeds. I must have definitely done something bad in my past life due to which I am suffering now.” (50-year-old Mr. BM.)Others who were addicted to substances (nicotine, alcohol, gutka, and other addictive substances) either expressed anger and:

- Blamed themselves (for using the substances),

- Blamed the substances, or

- Blamed the government (for not banning the substances) for their present illness.

“Because of my own self — My bidi and alcohol habits I have got cancer. I have only myself to blame for the illness.” (49-year-old Mr. P.)“Tobacco is the main cause of the illness. It should be banned.” (60-year-old Mr. D.)“The government is to be blamed for the illness of cancer in the society. If they had banned or taxed tobacco heavily, people would have been deterred from using it.” (42-year-old RG.)As seen above, the common object of blame for the illness is either God/fate, own self, substances that are addictive, or the state for not adhering to stringent norms for the sale of such addictive substances.

-

Coping strategies of the patients

There were mainly four themes that depicted the manner in which the patients coped with their emotions. These themes were:

Inculcating a positive attitude,

Developing a strong faith in the doctor/God,

Ventilating emotions with family/friends and their responses, and

-

Indulging in activities to divert attention:

-

Inculcating a positive attitude: To help them cope with the illness of cancer, some patients inculcated a strong positive attitude within themselves about their recovery.“I believe that there is no point in brooding over the illness. Hence, I did not feel upset and managed by telling myself that everything will be alright.” (42-year-old Mr. RKC.)“My strong positive attitude and my will power have helped me to maintain a balanced outlook and are helping me to handle my emotions towards my illness.” (49-year-old Mr. P.)“Life is full of hardships, which every man has to deal with by himself. Hence, I kept telling myself that this problem too shall be solved.” (32-year-old Mr. T.)Participants demonstrated a strong will power to be able to deal with the illness and used metaphors that aided in coping. Earlier studies too have depicted that metaphorical talk about cancer reflects enduring metaphorical patterns of thought in the patients.[24]

-

Developing a strong faith in the doctor/God: The strong faith that they will be taken care of by their doctor and their God helped some patients to cope with their illness.“I cope with my emotions on my own — By saying my prayers. I have a lot of faith in my God and I know that everything will be alright soon.” (60-year-old Mr. D.)“I have a lot of faith in my God and my doctor. They both are my sources of strength, and unquestionable faith in them has helped me cope with my emotions about the illness.” (42-year-old Mr. RG.)“I am in the hands of one of the best doctors in this field. I have full faith in my doctor's treatment and I know that I will get well soon.” (42-year-old Mr. NS.)The role of spirituality in coping is seen in the above narratives. When this is reiterated by professionals, this method of coping is further reinforced.

-

Ventilating emotions with family/friends and their responses: A majority of the participants had their families and relatives/friends to support and reassure them. They coped with the illness by sharing their emotions with them.“To help reduce my sadness, I used to talk to my family members, as they always instill hope and courage in me.” (47-year-old Mr. C.)“Reassurances from my family and my doctor that I will get well helped me to overcome my tension and worries a bit.” (55-year-old Mr. M.)“As my family is in the village and I have come alone to Mumbai for my treatment, I share my emotions with my copatients in the ward and feel better.” (35-year-old Mr. S.)The above quotes depict that the main sources of emotional support for the participants were their family members and in some cases their doctor. This use of human resources and social networks (especially one's family) to deal with ones emotions is characteristic of the strong Indian family system in India.

-

Indulging in activities to divert attention: Patients who did not want to make their families worry and those who were alone during their treatment process often kept their emotions to themselves and consciously indulged in activities to divert their attention.“I tried to divert my mind to other activities such as knitting and prayer so that I would not get any negative emotions and thoughts.” (50-year-old Mrs. F.)“My family is in the village and I have no one to talk to here at the hospital. Hence, I divert my mind, by consoling and counseling other fellow patients in the ward. I laugh and joke around with them so that they can forget about their illness at least when they are with me.”(35-year-old Mr. MM.)

-

Discussion

The content analysis of the qualitative results of the study puts forth a conceptual framework for understanding the emotions experienced and the coping strategies of head and neck cancer patients in India after diagnosis [Figure 1]. One's knowledge about his/her illness of cancer and the duration of untreated illness of cancer affects the emotions of a survivor. He/she experiences emotions of sadness, anxiety, loss of hope, fear, and blame. Depending on his/her family support system, inner resilience, and religious leanings (faith in God), the survivor is able to cope with his/her illness through strategies such as:

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of emotions and coping strategies of patients suffering from head and neck cancer

Inculcating a positive attitude,

Developing a strong faith in the doctor/God,

Ventilating emotions with family/friends and their responses, and

Indulging in activities to divert attention.

Though a number of studies have discussed the varied psychosocial issues experienced by the patients and the contexts in which they arise,[8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] this study particularly highlights the negative emotions of the patients to two main themes: being told about the illness and the duration of untreated illness. Divulging the news or discovery of the illness is equivalent to the concept of “breaking the bad news” and emotions experienced by the patients after the doctors or their families have disclosed the “bad news” of cancer to them.[25] However, understanding the phenomenon of the patient's “knowing” is essential for any health care professional working with cancer patients in order to understand and provide for their psychosocial needs.[26]

The Indian family is an integral part of the treatment process. The strong family ties and lineages act as a support system as well as a buffer for any individual,[27] especially in the case of patients of chronic ailments such as cancer. Most patients in India are able to ventilate their emotions to their family members and/or relatives who stand by them through their treatment. Studies reiterate that “ventilation of one's emotions” is an effective method of coping, which predicts the distress levels[28] and reduces medical visits for cancer-related morbidities.[29] Encouraging this culturally accepted coping method could help patients in India to deal better with their diagnosis of cancer.

In India, people have a strong religious orientation, which is often linked to their God. They have a philosophical understanding of life/death and other experiences. Most of the religious scriptures (e.g., Bhagavad Gita) reiterate that it is easier for people to cope when there is a grounded sense of God because it helps them to surrender to the Supreme/Unknown and feel secure. Some of the alternate therapies such as Pranic healing, Reiki, Art of Living, and yoga use aspects of prayer and meditation to help the person practice alone in the process of healing. These religious practices and beliefs are also seen to improve the inner resilience of cancer patients,[30,31] apart from being effective coping mechanisms.

The “object of blame” was considered as a separate theme for a better understanding of the emotions of cancer patients in this study as the concept of blame is inbuilt in the karma theory (as explained in the ancient Indian scriptures such as the Bhagavad Gita), which states that “one reaps the consequences of one's actions” and “one suffers from a disease such as cancer because of his/her misdeeds, either in this life or in a previous existence.” In such a scenario, the patient either blames himself/herself, others, or his/her fate, which facilitates acceptance of the disease by the survivor easily. While this concept may seem to be limiting, it also helps to “project the blame” to an unknown but sure source or object, thus freeing the individual to focus on dealing with the present reality (a type of defense mechanism). It can be inferred, therefore, that such a strategy can either help in coping if used in a moderate amount or be considered as negative coping (if excessively used). Palliative care professionals need to be aware of these cultural and religious ideologies while providing psychosocial care to Indian cancer patients.

The largely negative emotions expressed by the patient could be attributed to the fact that all had undergone surgery recently and the surgical process itself could have impacted their emotional and mental health. The dynamics and interplay between the internal and external resources of the patient had a bearing on the coping strategies used by the patient. It is further interesting to note that all the patients in spite of the condition of their disease were able to cope by using at least one strategy to deal with their emotional and mental state. No patient was observed as getting overwhelmed by his/her emotions or by stating that he/she wanted to die. Further, none of them had been provided any psychosocial intervention yet to help them deal with their condition, as they had undergone surgery only a few days prior to the interview.

This research finding brings out a very important inference, which can be used in the oncological care for patients with head and neck cancers: In this context, focus on psychosocial intervention for the promotion of effective and healthy coping strategies is essential, especially soon after surgery. As a well-being promotion intervention, it is useful to design strategies that locate the distress, detract from it, and project it in a suitably acceptable and conducive manner and then move on to replace the distress with deflective interventions with an aim to build and strengthen the resilience in the individual suffering from head and neck cancers.

Though the generalization of the results of this study is limited by the inclusion criteria which was fairly homogenous and being country specific, the researchers believe that the results of this study are a significant contribution to the field of psychosocial oncology. Further, the conceptual framework of this study could form a base for future quantitative studies that want to test the efficacy of any need-based psychosocial program for inpatients with head and neck cancers. This result however, needs to be tested outside India as the context of the emotions experienced by inpatients, the type of emotions expressed as well as the coping strategies could differ from culture to culture based on their underlying mores, ideologies, faiths, religions, and beliefs[13,31,32,33] that have a bearing on the coping of patients in that culture.

Financial support and sponsorship

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Tata Memorial Hospital [TMH], Mumbai, Maharashtra, India for permitting us to conduct this study and Dr. Savita Goswami, clinical psychologist of TMH for facilitating the data collection process.

References

- 1.Brown LF, Kroenke K, Theobald DE, Wu J, Tu W. The association of depression and anxiety with health-related quality of life in cancer patients with depression and/or pain. Psychooncology. 2010;19:734–41. doi: 10.1002/pon.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zenger M, Glaesmer H, Höckel M, Hinz A. Pessimism predicts anxiety, depression and quality of life in female cancer patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:87–94. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehnert A, Lehmann C, Graefen M, Huland H, Koch U. Depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and health-related quality of life and its association with social support in ambulatory prostate cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2010;19:736–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Given CW, Given BA, Stommel M. The impact of age, treatment, and symptoms on the physical and mental health of cancer patients. A longitudinal perspective. Cancer. 1994;74(Suppl):2128–38. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941001)74:7+<2128::aid-cncr2820741721>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuinman MA, Hoekstra HJ, Fleer J, Sleijfer DT, Hoekstra-Weebers JE. Self-esteem, social support, and mental health in survivors of testicular cancer: A comparison based on relationship status. Urol Oncol. 2006;24:279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley S, Rose S, Lutgendorf S, Costanzo E, Anderson B. Quality of life and mental health in cervical and endometrial cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:479–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gore JL, Krupski T, Kwan L, Maliski S, Litwin MS. Partnership status influences quality of life in low-income, uninsured men with prostate cancer. Cancer. 2005;104:191–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rust C, Davis C. Chemobrain in underserved African American breast cancer survivors: A qualitative study. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:E29–34. doi: 10.1188/13.CJON.E29-E34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker P, Beesley H, Dinwoodie R, Fletcher I, Ablett J, Holcombe C, et al. ‘You’re putting thoughts into my head’: A qualitative study of the readiness of patients with breast, lung or prostate cancer to address emotional needs through the first 18 months after diagnosis. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1402–10. doi: 10.1002/pon.3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kvåle K. Do cancer patients always want to talk about difficult emotions?. A qualitative study of cancer inpatients communication needs. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11:320–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nissam R, Zimmermann C, Minden M, Rydall A, Yuen D, Mischitelle A, et al. Abducted by the illness: A qualitative study of traumatic stress in individuals with acute leukemia. Leuk Res. 2013;37:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krumwiede KA, Krumwiede N. The lived experience of men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39:E443–50. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.E443-E450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trevino KM, Archambault E, Schuster JL, Hilgeman MM, Moye J. Religiosity and spirituality in military veteran cancer survivors: A qualitative perspective. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2011;29:619–35. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2011.615380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimsbø GH, Finset A, Ruland CM. Left hanging in the air: Experiences of living with cancer as expressed through E-mail communications with oncology nurses. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34:107–16. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181eff008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mireskandari S, Sangster J, Meiser B, Thewes B, Groombridge C, Spigelman A, et al. Psychosocial impact of familial adenomatous polyposis on young adults: A qualitative study. J Genet Couns. 2009;18:409–17. doi: 10.1007/s10897-009-9231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beatty L, Oxlad M, Koczwara B, Wade TD. The psychosocial concerns and needs of women recently diagnosed with breast cancer: A qualitative study of patient, nurse and volunteer perspectives. Health Expect. 2008;11:331–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akyüz A, Güvenç G, Ustünsöz A, Kaya T. Living with gynecologic cancer: Experience of women and their partners. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2008;40:241–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bebbington Hatcher M, Fallowfield LJ. A qualitative study looking at the psychosocial implications of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. Breast. 2006;12:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9776(02)00135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howell D, Fitch MI, Deane KA. Impact of ovarian cancer perceived by women. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200302000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crane JN. Religion and cancer: Examining the possible connections. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27:469–86. doi: 10.1080/07347330903182010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yanez B, Edmondson D, Stanton AL, Park CL, Kwan L, Ganz PA, et al. Facets of spirituality as predictors of adjustment to cancer: Relative contributions of having faith and finding meaning. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:730–41. doi: 10.1037/a0015820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jagannathan A, Juvva S. Life after cancer in India: Coping with side effects and cancer pain. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27:344–60. doi: 10.1080/07347330902979150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood S, Bisson JI. Experience of incorporating a mental health service into patient care after operations for cancers of the head and neck. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;42:149–54. doi: 10.1016/S0266-4356(03)00241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibbs RW, Jr, Franks H. Embodied metaphor in women's narratives about their experiences with cancer. Health Commun. 2002;14:139–65. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1402_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dias L, Chabner BA, Lynch TJ, Jr, Penson RT. Breaking bad news: A patient's perspective. Oncologist. 2003;8:587–96. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-6-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tobin GA, Begley C. Receiving bad news: A phenomenological exploration of the lived experience of receiving a cancer diagnosis. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31:E31–9. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305767.42475.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madan GR. 4th ed. New Delhi: Allied Publishers Private Ltd; 1987. Indian Sociology. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Compas BE, Stoll MF, Thomsen AH, Oppedisano G, Epping-Jordan JE, Krag DN. Adjustment to breast cancer: Age-related differences in coping and emotional distress. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;54:195–203. doi: 10.1023/a:1006164928474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Sworowski LA, Collins CA, Branstetter AD, Rodriguez-Hanley A, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of written emotional expression and benefit finding in breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4160–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gall TL, Cornblat MW. Breast cancer patients give voice: A qualitative analysis of spiritual factors in long-term adjustment. Psychooncology. 2002;11:524–35. doi: 10.1002/pon.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gall TL. Integrating religious resources within a general model of stress and coping: Long-term adjustment to breast cancer. J Relig Health. 2000;39:167–82. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lourens M. An exploration of Xhosa speaking patients’ understanding of cancer treatment and its influence on their treatment experience. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2013;31:103–21. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2012.741091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan CL, Ho RT, Lee PW, Cheng JY, Leung PP, Foo W, et al. A randomized controlled trial of psychosocial interventions using the psychophysiological framework for Chinese breast cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2006;24:3–26. doi: 10.1300/J077v24n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.New Delhi: Planning Commission Publication; 2001. Government of India. Tenth Five Year Plan (2002-2007) [Google Scholar]