Abstract

Introduction:

The duration, methods and frequency of radiographic follow-up after pediatric pyeloplasty is not well-defined. We prospectively evaluated a cohort of children undergoing pyeloplasty to determine the method for follow-up.

Methods:

Between 2000 and 2008, children undergoing pyeloplasty for unilateral ureteropelvic junction obstruction were evaluated for this study. All patients were evaluated preoperatively with protocol ultrasound (USG) and diuretic renal scan (RS). On the basis of preoperative split renal function (SRF), these patients were divided into four groups – Group I: SRF > 40%, Group II: SRF 30–39%, Group III: SRF 20–29%, and Group IV: SRF 10–19%. In follow-up, USG and RS were done at 3 months and repeated at 6 months, 1 year, and then yearly after surgery for a minimum period of 5 years. Improvement, stability, or worsening of hydronephrosis was based on the changes in anteroposterior (AP) diameter of pelvis and caliectasis on USG. Absolute increase in split renal function (SRF) >5% was considered significant. Failure was defined as increase in AP diameter of pelvis and decrease in cortical thickness on 3 consecutive USG, t½ >20 min with obstructive drainage on RS and/or symptomatic patient.

Results:

145 children were included in the study. Their mean age was 3.26 years and mean follow-up was 7.5 years. Pre- and post-operative SRF remain unchanged within 5% range in 35 of 41 patients (85%) in Group I. While 9 of 20 patients (45%) in Group II, 23 of 50 patients (46%) in Group III, and 14 of 34 patients (41%) in Group IV exhibited changes >5% after surgery. 5 patients failed, 2 in Group III, and 3 in Group IV. None of the patients deteriorated in Group I and II.

Conclusion:

After pyeloplasty in children with a baseline split GFR >30%, if a diuretic renogram and USG performed 3 months postoperatively shows nonobstructive drainage with t½ <20 min and decreased hydronephrosis, no further follow-up is required.

Key words: Children, follow-up, pyeloplasty, renal scans

INTRODUCTION

Ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO) is the most common form of obstruction in the children.[1] It is reported to occur in 1:500–1:1250 live births.[2,3] Surgical repair is indicated for significantly impaired renal drainage or progressive deterioration of renal function. Other indications for active intervention are to relieve pain or treat pathologies secondary to obstruction such as calculi and infections.[4,5]

Pyeloplasty is followed by an improvement in the renal dilatation and excretion pattern in up to 98% of patients.[6] Despite high reported success rates, there are no established recommendations to guide follow-up modality, timing, or duration after pediatric pyeloplasty. Many modalities have been suggested, including intravenous pyelography (IVP), radionucleotide renography, magnetic resonance urography,[7] and ultrasonography (USG), either alone or in combination at various time intervals.

USG and diuretic renal scan (RS) are the most widely used investigations for diagnosis and postoperative follow-up.[8] The success of pyeloplasty is based on the serial USG improvement of pelvicalyceal dilatation and improved drainage on RS with possible recovery of split renal function (SRF) in addition to clinical improvement. However, the duration of such scans long-term renal function on consecutive RS is not clear. Therefore we aimed to determine the appropriate duration and method of follow-up of these children.

METHODS

Children undergoing Anderson-Hynes dismembered pyeloplasty with double J stent for unilateral UPJO at our tertiary care hospital between January 2000 and December 2008 were included for this study. Patients with bilateral disease, vesicoureteral reflux, solitary functioning kidney, recurrent UPJO, and patients in whom the follow-up is less than 5 years were excluded.

All patients were evaluated preoperatively with protocol renal USG (i.e., anteroposterior [AP] diameter of the pelvis with cortical thickness at each pole of the kidney) and technetium-99m ethylene dicysteine (99m Tc-EC) diuretic RS (F '0' diuretic renogram). Society for fetal urology (SFU) grading system was used for hydronephrosis.[9] Data obtained from the RS reports included SRF and the presence or absence of significant obstruction, defined as t½ >20 min with an obstructive drainage curve. Obstruction was ruled out if t½ was <10 min. A t½ of 10–20 min was considered equivocal. The indication for surgery was based on the symptoms of pain, fever or lump in the abdomen; or decreased cortical thickness on USG (<5 mm), and obstructed drainage on RS.

On the basis of preoperative SRF, these patients were divided into four groups: Group I: SRF >40%, Group II: SRF 30–39%, Group III: SRF 20–29%, and Group IV: SRF 10–19%. In follow-up, patients were evaluated for symptoms, physical examination along with USG and RS, at 3 months and repeated at 6 months, 1 year, and then yearly after surgery for a minimum period of 5 years.

On USG, improvement, stability, or worsening of hydronephrosis was based on changes in AP renal pelvic diameter and caliectasis. On RS, improvement, stability, or worsening in renal function was based on changes in SRF. An absolute increase in SRF of more than 5% in the operated kidney was considered significant. Failure was defined as an increase in AP diameter of pelvis and decrease in cortical thickness on 3 consecutive USG, t½ >20 min with obstructive drainage on postoperative 99m Tc-EC scan and/or symptomatic patient.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon signed ranks test. Written informed consent of all patients was taken. Institutional ethics and review board approval were obtained.

RESULTS

A total of 104 boys and 41 girls who underwent 145 pyeloplasties met the inclusion criterion. Boys to girl's ratio were 2.54. Mean age was 3.26 years at the time of operation (range 6 months to 10 years). Laparoscopic pyeloplasty was performed in 122 (84.13%) and open surgery in 23 (15.8%). 67 patients (46%) were operated on the right side, and 78 (54%) were on the left side. A total of 30 patients were diagnosed prenatally and 115 postnatally. The main indications for surgery were symptomatic obstruction with pain (47 cases), mass (19), or infection (15), obstructive RS (39), with secondary calculi (6) and worsening hydronephrosis (19).

There were 41, 20, 50, and 34 children in Group I, II, III, and IV, respectively. Preoperative RS was reported as obstructive in 136 kidneys and equivocal in 9. Of the 9 equivocal studies, 3 patients were symptomatic (pain), 4 exhibited worsening hydronephrosis, and 2 had a reduction in differential renal function. Preoperatively USG revealed Grade III and IV hydronephrosis in 99 and 46 patients respectively.

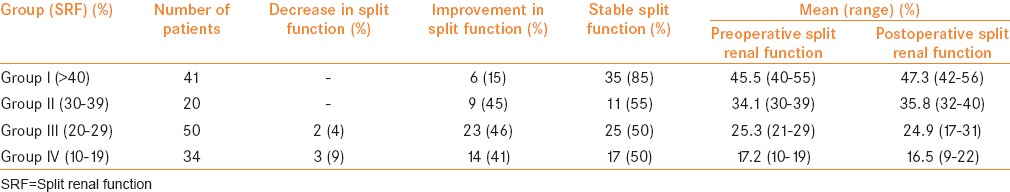

The mean follow-up was 5 years. During follow-up, 140 patients had improvement in hydronephrosis and decreased caliectasis. The number of children with Grade II, III, and IV hydronephrosis was 43, 72, and 30 respectively. 5 patients had worsening of hydronephrosis with concomitant obstructive drainage on RS. Postoperative RS was reported as obstructive in these 5 children and nonobstructive in the remaining 140. Changes in SRF after pyeloplasty are given in Table 1a.

Table 1a.

Details of split renal function pre- and post-pyeloplasty

None of the patients in Group I (41 patients) or Group II (20 patients) showed a deterioration in function. In Group III (50 patients), 2 (4%) patients deteriorated while in Group IV (34 patients), 3 patients (9%) deteriorated. These 5 kidneys showed no improvement on postoperative USG. Two exhibited Grade III, and three exhibited Grade IV hydronephrosis preoperatively, while all five exhibited worsening of hydronephrosis postoperatively.

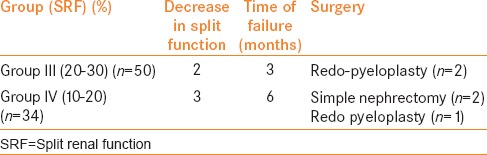

Redo pyeloplasty was performed in 2 patients belonging to Group III with preoperative Grade III hydronephrosis and 22% and 16% SRF with a t½ of 22 and 25 min, respectively. The initial postoperative USG and RS showed Grade IV hydronephrosis and obstructive drainage at 3 months in these 2 patients.

The remaining 3 patients belonging to Group IV showed no improvement on initial postoperative USG, and the postoperative RS was obstructive. One was treated successfully by redo pyeloplasty while in 2 patients, a palpable abdominal mass developed postoperatively with high-grade fever and SRF declined to less than 5%. Percutaneous nephrostomy was placed initially which drained pus and later both underwent nephrectomy [Table 1b].

Table 1b.

Details of cases which failed

DISCUSSION

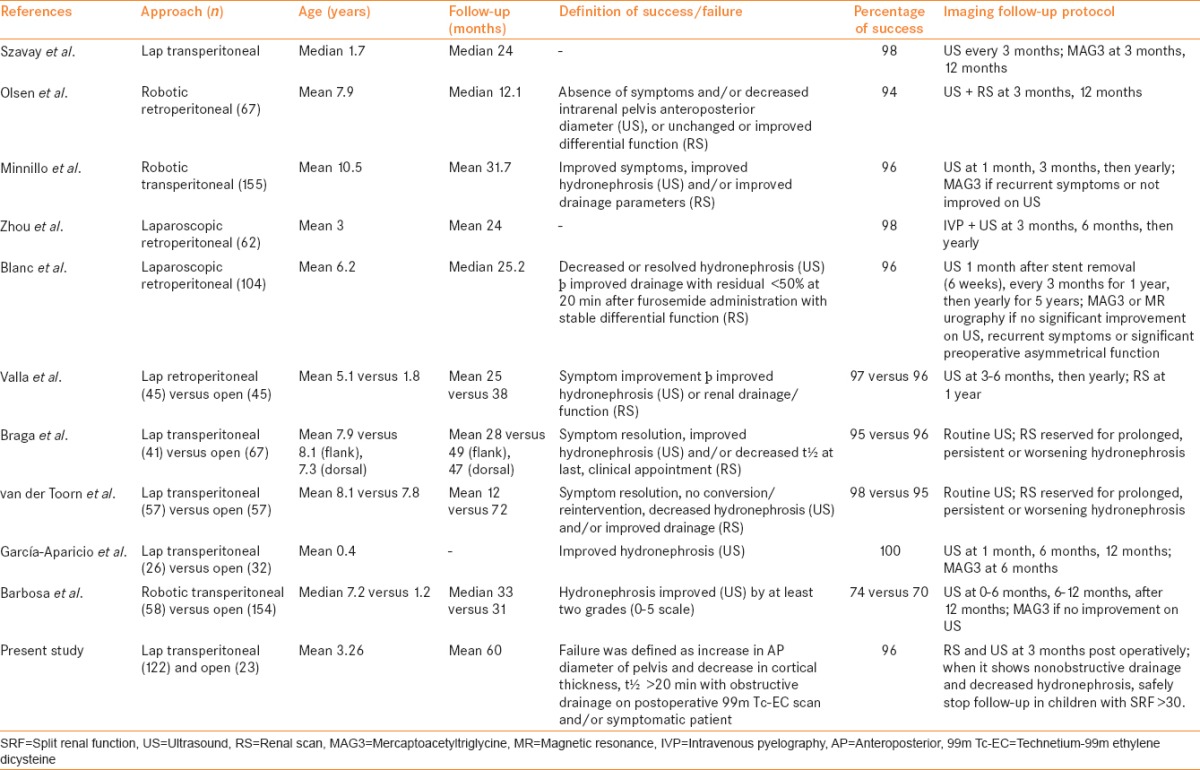

The purpose of imaging after pyeloplasty is to diagnose obstruction early so that interventions may prevent further nephron loss. Success after pyeloplasty for the repair of UPJO in children has been routinely defined by a combination of clinical and radiographic criteria. In postpyeloplasty follow-up, USG and RS are the most widely used investigations. However, there is variation in modality and frequency of imaging follow-up.[10] Contemporary series on pediatric pyeloplasty have revealed high success rates, although differing protocols exist regarding imaging surveillance [Table 2].[11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]

Table 2.

Selected contemporary series on pediatric pyeloplasty including at least 50 cases

USG has been used in the pediatric population in assessing outcome after pyeloplasty by measuring changes in the AP pelvic diameter. It has been suggested that patients in whom postoperative USG reveals downgrading of AP pelvic diameter, may not require renograms to rule out the obstruction. However, difficulties with USG include operator variability, slower improvement in hydronephrosis compared with improvement seen on renogram, and the difficulties of differentiating between a dilated and an obstructed renal pelvicalyceal system. There are many variables that are not controlled for during the examination such as the level of pre-USG hydration or the amount of urine in the bladder. These factors can affect the level of hydronephrosis and thus affect clinical decision-making. Early improvement on USG could also be due to surgical reduction of the renal pelvis rather than true improvement.

Postoperative diuretics renogram is generally used to answer two questions, namely, relief of obstruction and functional recovery. Although there are arguments against radionucleotide renography, most published data demonstrate its superiority in the ability to determine obstruction. RS showing improved or stable function and better drainage can be regarded as proof of successful surgery and is usually performed as a baseline to subjectively document the surgical outcome.[21] The timing and frequency of postoperative RS have become the subject of recent publications.

More recently, several groups have questioned whether even early postoperative renography is necessary after pediatric pyeloplasty. Use of a sentinel USG instead has been advocated to determine if renography is necessary. Almodhen et al. reported on 97 patients who underwent 101 pyeloplasties with a mean follow-up of 4.5 years. Of the 91 kidneys with improvement on postoperative USG, 2 (2%) exhibited an obstructive pattern on renography, although both spontaneously improved during follow-up. Hydronephrosis was downgraded in 46 kidneys, and none of these kidneys exhibited an obstructive postoperative scan. Of the 10 kidneys with worsened or no improvement on postoperative USG, 4 (40%) had an obstructive renogram, of which 2 were treated with a subsequent procedure. They conclude that those with preoperative function <45% may exhibit functional changes >5% that can be determined by postoperative RS.[22] Cost et al. observed similar findings in 49 patients undergoing open pyeloplasty who underwent US and renography at 3 months. Of the 42 children with stable or improved hydronephrosis, 41 had stable function, and one had low function (32% split function) preoperatively but remained stable (21% split function) at longer follow-up. Of the 7 remaining patients with increased hydronephrosis 2 had worse renal function.[23] In this study, 5 patients failed, 2 in Group III, and 3 in Group IV. None of the patient deteriorated in Group I and II.

van den Hoek et al. reported that SRF remained unchanged within the 5% range in 75 of 87 patients (86%) with initial preoperative function > 40%. In that series, only 3 patients (3%) demonstrated significant deterioration to <40%, while 27 of 51 patients (53%) with initial function <40% exhibited changes > 5% following surgery. Moreover, it was observed that SRF after pyeloplasty remained unchanged at 5–7 years compared to the initial 9-month postoperative RS. Thus, repeat RS at 5–7 years after pyeloplasty was not justified.[21] Similarly, our data reveal that SRF remained unchanged within 5% range in 35 of 41 patients (85%) in Group I, while 11 of 20 patients (55%) in Group II, 23 of 50 patients (46%) in Group III, and 14 of 34 patients (41%) in Group IV exhibited changes > 5% after surgery.

Pohl et al., suggested that follow-up can be discontinued as early as 3 months postoperatively if diuretic renogram show t½ <20 min. Their data indicate that when an unobstructed 3 months renogram is followed by 1-year renogram, the second renogram never shows deterioration in drainage, and therefore, is not necessary.[6] Tveter et al. also noted the similar observations.[24]

Psooy et al. showed that after an unobstructed diuretic renogram, recurrence of the obstruction was unlikely and did not justify a long-term follow-up. They followed their patients radiographically with excretory urography (IVP) at 2 months; renal USG at 6 month and RS at 1 year.[25] However, with the emergence of USG and radionucleotide renography, IVP is of historical interest. There were no data on SRF in their study, and there was no subdivision of patients in groups. O'Reilly et al. used a repeat RS in 24 patients at 6–19 years after surgery and concluded that the results were durable.[26]

Chandrasekharam et al. reported that in 68 children with symptomatic pelviureteric junction obstruction, RSs were taken 3 months, 1, 2, and 5 years after surgery, and it was concluded that in patients with impaired preoperative function, the improvement in SRF continued until 1 year after surgery. There was no further improvement after that period, and the SRF remained stable.[27]

Although the vast majority of failures occur within 1 year after pyeloplasty. Follow-up repeat renography in a group of patients may help to reassure both the patient and surgeon that any ongoing symptoms are not due to persistent or worsening UPJO, and it act as a baseline to subjectively document the surgical outcome, as USG is operator dependant modality and not done by the same radiologist at our institute. A single renogram at 3 months is adequate, without the need of further repeat renography thereafter in Group I and II.

In this study, the limitation is number of RSs, which might associated with the radiation exposure.[28,29] However, it can be discussed that this risk is small. Another limitation is that USG studies performed under standardized conditions could have been influenced by the state of hydration, bladder fullness, and sonographic techniques. However, the prospective nature of the study and the substantial number of cases in each group and subdivisions of patients into subgroups according to SRF with longer follow-up contributed to the strength of this study.

CONCLUSIONS

After an unobstructed postoperative diuretic renogram at 3 months, recurrent UPJO is unlikely and does not justify long-term follow-up even in case of impaired SRF after surgery, as most renal units remain stable. After pediatric pyeloplasty, if a diuretic renogram and USG 3 months postoperatively shows nonobstructive drainage with t½ <20 min and decreased hydronephrosis, we can safely stop follow-up in children with SRF > 30.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aksu N, Yavascan O, Kangin M, Kara OD, Aydin Y, Erdogan H, et al. Postnatal management of infants with antenatally detected hydronephrosis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:1253–9. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-1989-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arger PH, Coleman BG, Mintz MC, Snyder HP, Camardese T, Arenson RL, et al. Routine fetal genitourinary tract screening. Radiology. 1985;156:485–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.156.2.3892578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grignon A, Filiatrault D, Homsy Y, Robitaille P, Filion R, Boutin H, et al. Ureteropelvic junction stenosis: Antenatal ultrasonographic diagnosis, postnatal investigation, and follow-up. Radiology. 1986;160:649–51. doi: 10.1148/radiology.160.3.3526403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joyner BD, Mitchell ME. Ureteropelvic junction obstruction. In: Grosfeld JL, O'Neill JA, Coran AG, Fonkalsrud EW, editors. Pediatric Surgery. 5th ed. Missouri: Mosby Year Book; 1996. pp. 1591–604. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mouriquand P. Congenital anomalies of the pyeloureteral junction. In: Grosfeld JL, Fonkalsrud EW, Coran AG, editors. Pediatric Surgery. 5th ed. Missouri: Mosby Year Book; 1996. pp. 1591–604. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pohl HG, Rushton HG, Park JS, Belman AB, Majd M. Early diuresis renogram findings predict success following pyeloplasty. J Urol. 2001;165(6 Pt 2):2311–5. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirsch AJ, McMann LP, Jones RA, Smith EA, Scherz HC, Grattan-Smith JD. Magnetic resonance urography for evaluating outcomes after pediatric pyeloplasty. J Urol. 2006;176(4 Pt 2):1755–61. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.03.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salem YH, Majd M, Rushton HG, Belman AB. Outcome analysis of pediatric pyeloplasty as a function of patient age, presentation and differential renal function. J Urol. 1995;154:1889–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernbach SK, Maizels M, Conway JJ. Ultrasound grading of hydronephrosis: Introduction to the system used by the society for fetal urology. Pediatr Radiol. 1993;23:478–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02012459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsi RS, Holt SK, Gore JL, Lendvay TS, Harper JD. National trends in followup imaging after pyeloplasty in children in the United States. J Urol. 2015;194:777–82. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.03.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szavay PO, Luithle T, Seitz G, Warmann SW, Haber P, Fuchs J. Functional outcome after laparoscopic dismembered pyeloplasty in children. J Pediatr Urol. 2010;6:359–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olsen LH, Rawashdeh YF, Jorgensen TM. Pediatric robot assisted retroperitoneoscopic pyeloplasty: A 5-year experience. J Urol. 2007;178:2137–41. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minnillo BJ, Cruz JA, Sayao RH, Passerotti CC, Houck CS, Meier PM, et al. Long-term experience and outcomes of robotic assisted laparoscopic pyeloplasty in children and young adults. J Urol. 2011;185:1455–60. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou H, Li H, Zhang X, Ma X, Xu H, Shi T, et al. Retroperitoneoscopic Anderson-Hynes dismembered pyeloplasty in infants and children: A 60-case report. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25:519–23. doi: 10.1007/s00383-009-2369-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanc T, Muller C, Abdoul H, Peev S, Paye-Jaouen A, Peycelon M, et al. Retroperitoneal laparoscopic pyeloplasty in children: Long-term outcome and critical analysis of 10-year experience in a teaching center. Eur Urol. 2013;63:565–72. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valla JS, Breaud J, Griffin SJ, Sautot-Vial N, Beretta F, Guana R, et al. Retroperitoneoscopic vs open dismembered pyeloplasty for ureteropelvic junction obstruction in children. J Pediatr Urol. 2009;5:368–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2009.02.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braga LH, Lorenzo AJ, Bägli DJ, Mahdi M, Salle JL, Khoury AE, et al. Comparison of flank, dorsal lumbotomy and laparoscopic approaches for dismembered pyeloplasty in children older than 3 years with ureteropelvic junction obstruction. J Urol. 2010;183:306–11. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Toorn F, van den Hoek J, Wolffenbuttel KP, Scheepe JR. Laparoscopic transperitoneal pyeloplasty in children from age of 3 years: Our clinical outcomes compared with open surgery. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9:161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.García-Aparicio L, Blazquez-Gomez E, Martin O, Manzanares A, García-Smith N, Bejarano M, et al. Anderson-hynes pyeloplasty in patients less than 12 months old. Is the laparoscopic approach safe and feasible? J Endourol. 2014;28:906–8. doi: 10.1089/end.2013.0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbosa JA, Kowal A, Onal B, Gouveia E, Walters M, Newcomer J, et al. Comparative evaluation of the resolution of hydronephrosis in children who underwent open and robotic-assisted laparoscopic pyeloplasty. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Hoek J, de Jong A, Scheepe J, van der Toorn F, Wolffenbuttel K. Prolonged follow-up after paediatric pyeloplasty: Are repeat scans necessary? BJU Int. 2007;100:1150–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almodhen F, Jednak R, Capolicchio JP, Eassa W, Brzezinski A, El-Sherbiny M. Is routine renography required after pyeloplasty? J Urol. 2010;184:1128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cost NG, Prieto JC, Wilcox DT. Screening ultrasound in follow-up after pediatric pyeloplasty. Urology. 2010;76:175–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.09.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tveter KJ, Nerdrum HJ, Mjolnerod OK. The value of radioisotope renography in the followup of patients operated upon for hydronephrosis. J Urol. 1975;114:680–3. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)67116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Psooy K, Pike JG, Leonard MP. Long-term followup of pediatric dismembered pyeloplasty: How long is long enough? J Urol. 2003;169:1809–12. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000055040.19568.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Reilly PH, Brooman PJ, Mak S, Jones M, Pickup C, Atkinson C, et al. The long-term results of Anderson-Hynes pyeloplasty. BJU Int. 2001;87:287–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandrasekharam VV, Srinivas M, Bal CS, Gupta AK, Agarwala S, Mitra DK, et al. Functional outcome after pyeloplasty for unilateral symptomatic hydronephrosis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2001;17:524–7. doi: 10.1007/s003830100604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner LK. Minimizing radiation injury and neoplastic effects during pediatric fluoroscopy: What should we know? Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36(Suppl 2):141–5. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0187-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleinerman RA. Cancer risks following diagnostic and therapeutic radiation exposure in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36(Suppl 2):121–5. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0191-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]