Abstract

There is significant interest in a better understanding of the genetic underpinnings of the increased glucose metabolic rates of cancer cells. Thyroid cancer demonstrates a broad variability of 18F-FDG uptake as well as several well-characterized oncogenic mutations. In this study, we evaluated the differences in glucose metabolism of the BRAFV600E mutation versus BRAF wild-type (BRAF-WT) in patients with metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) and poorly differentiated thyroid cancer (PDTC).

Methods

Forty-eight DTC and 34 PDTC patients who underwent 18F-FDG PET/CT for tumor staging were identified from a database search. All patients were tested for the BRAFV600E mutation and assigned to 1 of 2 groups: BRAFV600E mutated and BRAF-WT. 18F-FDG uptake of tumor tissue was quantified by maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of the hottest malignant lesion in 6 prespecified body regions (thyroid bed, lymph nodes, lung, bone, soft tissue, and other). When there were multiple lesions in 1 of the prespecified body regions, only the 1 with the highest 18F-FDG uptake was analyzed.

Results

In the DTC cohort, 24 tumors harbored a BRAFV600E mutation, whereas 24 tumors were BRAF-WT. 18F-FDG uptake of BRAFV600E-positive lesions (median SUVmax, 6.3; n = 53) was significantly higher than that of BRAF-WT lesions (n = 39; median SUVmax, 4.7; P = 0.019). In the PDTC group, only 5 tumors were BRAFV600E-positive, and their 18F-FDG uptake was not significantly different from the BRAF-WT tumors. There was also no significant difference between the SUVmax of all DTCs and PDTCs, regardless of BRAF mutational status (P = 0.90).

Conclusion

These data suggest that BRAFV600E-mutated DTCs are significantly more 18F-FDG–avid than BRAF-WT tumors. The effect of BRAFV600E on tumor glucose metabolism in PDTC needs further study in larger groups of patients.

Keywords: thyroid cancer, BRAFV600E-mutation, 18F-FDG uptake, DTC, PDTC

Thyroid cancer is a genetically heterogeneous disease that demonstrates a broad spectrum of glucose metabolic rates as shown by 18F-FDG PET/CT studies (1–3). Several studies have demonstrated that tumor 18F-FDG uptake of poorly differentiated thyroid cancer (PDTC) is higher than that of differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC). Furthermore, survival of patients with thyroid cancer has been shown to be inversely correlated to the intensity of 18F-FDG uptake as measured by maximum standardized uptake values (SUVmax) (4). These data suggest that 18F-FDG uptake is a reflection of tumor proliferation and aggressiveness. However, some well-differentiated thyroid cancers and even benign thyroid nodules can exhibit high 18F-FDG uptake (5). These clinical observations suggest that 18F-FDG uptake by thyroid tumors is not necessarily caused by rapid proliferation but may be due to genetic alterations causing accelerated glucose metabolism.

About 45% of papillary DTCs harbor a BRAFV600E mutation, whereas RAS mutations and RET/PTC rearrangements are less common (6,7). On the other hand, RAS mutations are more frequent in PDTCs (8,9). DTCs harboring a BRAFV600E mutation show a higher expression of glucose transporter 1 than those with wild-type (WT) BRAF, indicating that tumors with BRAFV600E may show a higher 18F-FDG uptake (10). A recently published multicenter study indicated a poorer prognosis for DTC patients harboring BRAFV600E mutation (11). Previous studies have also indicated that high 18F-FDG uptake in thyroid cancer points to poorer prognosis (4). However, to our knowledge, no published clinical data suggest a direct association between BRAFV600E status and 18F-FDG uptake.

In colorectal cancer as well as melanoma, BRAFV600E has been shown to regulate glycolysis independently of cell-cycle progression or cell death, also suggesting that BRAFV600E mutations may be associated with increased glycolysis (12,13).

We therefore hypothesized that thyroid cancers with BRAFV600E mutations demonstrate higher 18F-FDG uptake than BRAF-WT, irrespective of histologic characteristics. We tested this hypothesis in a retrospective study of DTC and PDTC patients who underwent 18F-FDG PET/CT for tumor staging and for whom the BRAFV600E mutational status was known.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

We performed an automated search for all DTC and PDTC patients who underwent 18F-FDG PET/CT and had a BRAF mutational status analysis performed on their primary tumors. Patients with secondary malignancies were excluded. The classification of tumors as DTC or PDTC is based on the interpretation of the histologic sections of the primary tumor by our institution’s Department of Pathology.

Sequenom mass spectrometry or next-generation sequencing was used to assess the mutational status of all patients. Not all of the tumor samples were investigated for other mutations such as RAS or RET/PTC; therefore, the patients were classified as BRAFV600E or BRAF-WT. Patient characteristics are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics of BRAFV600E and BRAF-WT Groups

| DTC | PDTC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | BRAFV600E | BRAF-WT | BRAFV600E | BRAF-WT |

| n | ||||

| PT genotype | 24 (2)* | 24 (2)* | 5 | 29 |

| Lesions† | 57 | 44 | 12 | 48 |

| Lesions per patient | ||||

| <5 | 13 | 16 | 3 | 17 |

| 5–10 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| >10 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 6 |

| 18F-FDG PET | ||||

| Positive | 21 | 19 | 5 | 20 |

| Negative | 3 | 5 | 0 | 9 |

| Age (y) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 68 ± 11‡ | 64 ± 11‡ | 72 ± 11§ | 61 ± 13§ |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 13 | 15 | 1 | 16 |

| Male | 11 | 9 | 4 | 13 |

| TNM | ||||

| TX | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| T1/a/b | 1/1/2 | 4/0/0 | 0/0/0 | 0/0/2 |

| T2/a/b | 2/0/0 | 5/0/0 | 1/0/0 | 7/0/0 |

| T3/a/b | 8/0/0 | 5/0/0 | 1/0/0 | 10/4/1 |

| T4/a/b | 2/3/1 | 3/1/3 | 0/2/0 | 0/2/3 |

| NX/0 | 4/6 | 4/11 | 1/1 | 0/18 |

| N1/a/b | 6/3/5 | 3/3/3 | 1/0/2 | 3/4/4 |

| MX/0/1 | 4/19/1 | 4/14/6 | 1/2/2 | 0/23/6 |

| Radioiodine (GBq)‖ | ||||

| Median/minimum/maximum | 5.8/3.7/30.5 | 7.4/2.6/32.7 | 2.7/1.1/4.4 | 7.4/1.9/24.5 |

| TSH (mU/L)¶ | ||||

| Median/minimum/maximum | 0.07/0.01/4.92 | 0.03/0.02/1.63 | 0.1/0.02/1.7 | 0.04/0.02/15.2 |

| Thyroglobulin (ng/mL)# | ||||

| Median/minimum/maximum | 6.9/0.2/1,930 | 360/0.3/37,000 | 46.9/2.2/670 | 270/1.7/1,4400 |

| PET to D | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 31 ± 41** | 24 ± 36** | 40 ± 51†† | 11 ± 26†† |

No. of patients, with follicular variant of PTC in parentheses.

Only 1 lesion per site per patient (Table 2) was analyzed.

P = 0.24, Mann–Whitney U test.

P = 0.10, Mann–Whitney U test.

All patients with DTC received radioiodine; amount of 131I missing in n = 26, n = 2 patients with PDTC did not receive radioiodine, n = 1 no data about radioiodine available, n = 8 amount of 131I missing.

For n = 2 patients with PDTC, no data were available.

For n = 4 patients with DTC and n = 3 patients with PDTC, no thyroglobulin data were available and n = 4 patients with DTC had thyroglobulin level below 0.3 ng/mL, but for all of these patients, progress was stated with CT. Difference of thyroglobulin values in WT DTC was significantly higher than in BRAFV600E group (P = 0.009).

P = 0.59, Mann–Whitney U test.

P = 0.16, Mann–Whitney U test.

PET to D = time difference between PET and diagnosis verified by molecular pathology, given in months.

Our institutional review board approved this retrospective study, and the requirement to obtain informed consent was waived.

18F-FDG PET/CT Imaging

Because we accrued patients over a period of 14 y, the PET/CT scans had been obtained with multiple scanner types. However, patient preparation and image acquisition protocols were comparable over the years. All scans were acquired using PET/CT cameras, including Discovery LS, Discovery ST, and Discovery STE (all GE Healthcare) or Biograph LSO-16 (Siemens Medical Solutions). No information on the scanner system was available for 22% of the patients. Patients were instructed to fast for at least 6 h before 18F-FDG administration, and blood glucose levels were required to be less than 200 mg/dL at the time of injection. The scans were acquired from the upper thighs to the base of the skull (5–7 bed positions) 60–90 min after injection of about 400 MBq of 18F-FDG. CT was performed for attenuation correction and anatomic localization. Immediately after the CT image acquisition, PET data were acquired for 3–5 min per bed position. The attenuation-corrected PET data were reconstructed using an ordered-subset expectation maximization iterative reconstruction.

Image Analysis

Lesions with the typical appearance of local recurrence or metastases on PET or CT were analyzed. Criteria for metastatic disease were focal 18F-FDG uptake above regional background that was not explained by the physiologic pattern of 18F-FDG uptake and excretion. In the absence of focal 18F-FDG uptake, standard CT morphologic criteria were used to define a malignant lesion. These included lytic bone lesions and lung nodules larger than 1 cm in diameter. The location of the lesions was classified as thyroid bed, lymph node, lung, bone, soft tissue, or other (Table 2). For each of these sites, 18F-FDG uptake was quantified for the lesion with the highest 18F-FDG uptake using SUVs normalized to the body weight of the patient. For measurement of SUVs, a spheric volume of interest encompassing the complete lesions was defined using the AW Volume Viewer Software (GE Healthcare). Areas of physiologic 18F-FDG uptake such as the myocardium were carefully excluded. Lesion size was measured on CT if the lesion was well delineated on the CT images. For lesions with insufficient contrast on CT (mostly bone lesions), tumor size was measured on PET as the maximum diameter of an isocontour defined by 45% of the maximum uptake within the lesion.

TABLE 2.

Localization of Lesions for BRAFV600E and BRAF-WT Groups

| DTC | PDTC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | BRAFV600E | BRAF-WT | BRAFV600E | BRAF-WT |

| Thyroid bed | 11* | 2* | 4 | 6 |

| Lymph node | 20† | 12† | 3 | 13 |

| Lung | 17 (3)‡ | 19 (5)‡ | 4 | 9 (9) |

| Bone | 3 | 10 | 0 | 4 (2) |

| Soft tissue | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Other | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Total number | 57 | 44 | 12 | 48 |

P = 0.008, Fisher exact test.

P = 0.031, Fisher exact test.

P = 0.049, Fisher exact test.

Data in parentheses are no. of 18F-FDG–negative lesions. Other sites were peritoneum (n = 1), adrenal gland (n = 1), liver (n = 3), and tumor thrombus (n = 1).

The highest standardized uptake value (SUV) (SUVmax) within the volume of interest was recorded. Only 1 lesion in the predefined sites (Table 2) was analyzed. For lesions considered malignant on CT, but showing no focal 18F-FDG uptake on PET, an SUVmax of −1 was recorded. We used this approach instead of recording the actual SUV at the site of the lesion because physiologic differences in background activity would otherwise significantly affect the SUV measurements. For example, a liver lesion that shows no focal 18F-FDG uptake could be assigned a higher SUV than a lung lesion with focal 18F-FDG uptake. Therefore, it seemed more appropriate to use a single SUV for all lesions that were not seen with positive contrast on PET.

We also analyzed whether there were differences between the SUVs of BRAFV600E and BRAF-WT patients when only the single lesion with the highest 18F-FDG uptake was analyzed. Because of the small number of patients with PDTC, this analysis was not performed for this group of patients.

Some of the 18F-FDG–positive lesions were small enough to be affected by partial-volume effects. In an attempt to minimize this effect on the comparison of the analyzed 2 groups, we performed a statistical test to rule out any differences in the distribution of the sizes of the lesions in the BRAFV600E and BRAF-WT groups (P = 0.27, Mann–Whitney U test).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical software GraphPad Prism (version 6.0; GraphPad Software, Inc.) was used to analyze the data. All reported P values were calculated using the 2-sided Mann–Whitney U test or Fisher exact test, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Forty-eight DTCs and 34 PDTCs were identified from the database search (2001–2005, n = 1; 2006–2010, n = 44; 2011–2013, n = 37). All patients had undergone surgery before the PET/CT study, and all but 2 patients with PDTC had received radioiodine therapy. Radioiodine scans under thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) stimulation were negative in all patients, but there was evidence for disease progression based on thyroglobulin levels or abnormal morphologic imaging findings. Seven DTC patients died during follow-up (n = 5 [21%] BRAFV600E and 2 [8%] BRAF-WT). Of the PDTC patients, 12 died during follow-up (n = 2 [40%] BRAFV600E and 10 [34%] BRAF-WT).

In the DTC group, 24 tumors had a confirmed BRAFV600E mutation, and 24 were classified as BRAF-WTV600E (10 of those designated BRAF-WT had a RAS mutation, and the other mutational status was unknown). The PDTC group comprised 34 patients; 5 had a BRAFV600E mutation and 29 were classified as BRAF-WT (15 of these had a RAS mutation). Patient characteristics including sex, age, TNM status, thyroglobulin/TSH values, and radioiodine treatments are given in Table 1. BRAFV600E and BRAF-WT groups did not differ with respect to the time from pathologically confirmed diagnosis to PET (P = 0.86 for DTC and 0.16 for PDTC patients, Mann–Whitney U test). We also performed a statistical test to verify a homogeneous distribution of the age of patients in the compared groups (DTC group with BRAFV600E and BRAF-WT, P = 0.24; PDTC group with BRAFV600E and BRAF-WT, P = 0.10, Mann–Whitney U test).

18F-FDG PET

In the DTC patients, 101 lesions were analyzed. The number of 18F-FDG–positive lesions in the BRAFV600E and BRAF-WT groups was 54 (53%) and 39 (39%), respectively. The number of 18F-FDG–negative lesions was 3 (3%) in the BRAFV600E group and 5 (5%) in the BRAF-WT group. Twenty of the 39 (51%) 18F-FDG–positive lesions in the BRAF-WT lesions harbored RAS mutations.

In the group of PDTCs, 60 lesions were analyzed. The number of 18F-FDG–positive lesions in the BRAFV600E group was 12 (20%), whereas none of the lesions in this group was 18F-FDG–negative. There were 37 (62%) 18F-FDG–positive and 11 (18%) 18F-FDG–negative lesions in the BRAF-WT PDTC group. Twelve of these 48 (25%) lesions in the BRAF-WT group harbored RAS mutations. Details about lesion characteristics are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

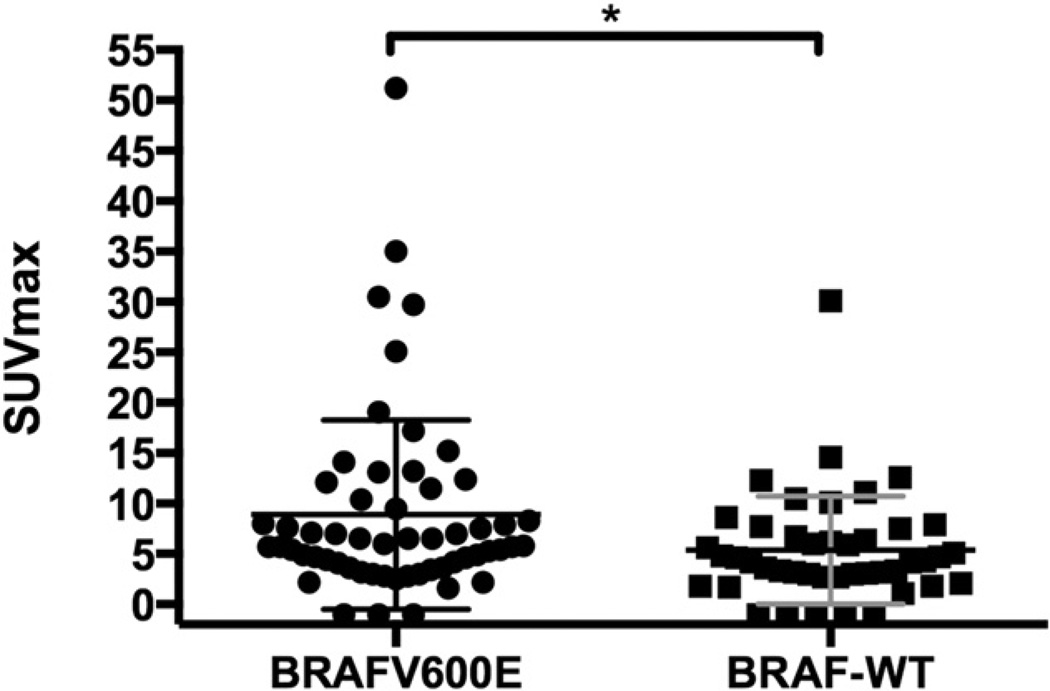

In the DTC group of patients, the BRAFV600E-positive lesions showed a significantly higher SUVmax than BRAF-WT lesions (P = 0.019, Mann–Whitney U test) (Table 3; Fig. 1). There was also a significant difference when comparing only the single lesion with the highest SUVmax per patient in the BRAFV600E and BRAF-WT groups (P = 0.04, Mann–Whitney U test).

TABLE 3.

Lesion Analysis of 18F-FDG–Positive BRAFV600Eand BRAF-WT Groups

| DTC | PDTC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Value | BRAFV600E | BRAF-WT | BRAFV600E | BRAF-WT |

| SUVmax | Median | 6.3 | 4.7 | 6.4 | 9.4 |

| Minimum | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 2.3 | |

| Maximum | 51.2 | 30.1 | 30.0 | 47.0 | |

| CT size (cm) | Mean ± SD | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 1.5 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 2.8 ± 1.9 |

| Median | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 2.2 | |

| Minimum | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | |

| Maximum | 3.8 | 7.8 | 4.5 | 8.0 | |

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of SUVmax for DTC patients harboring BRAFV600E mutation versus BRAF-WT. *P = 0.019.

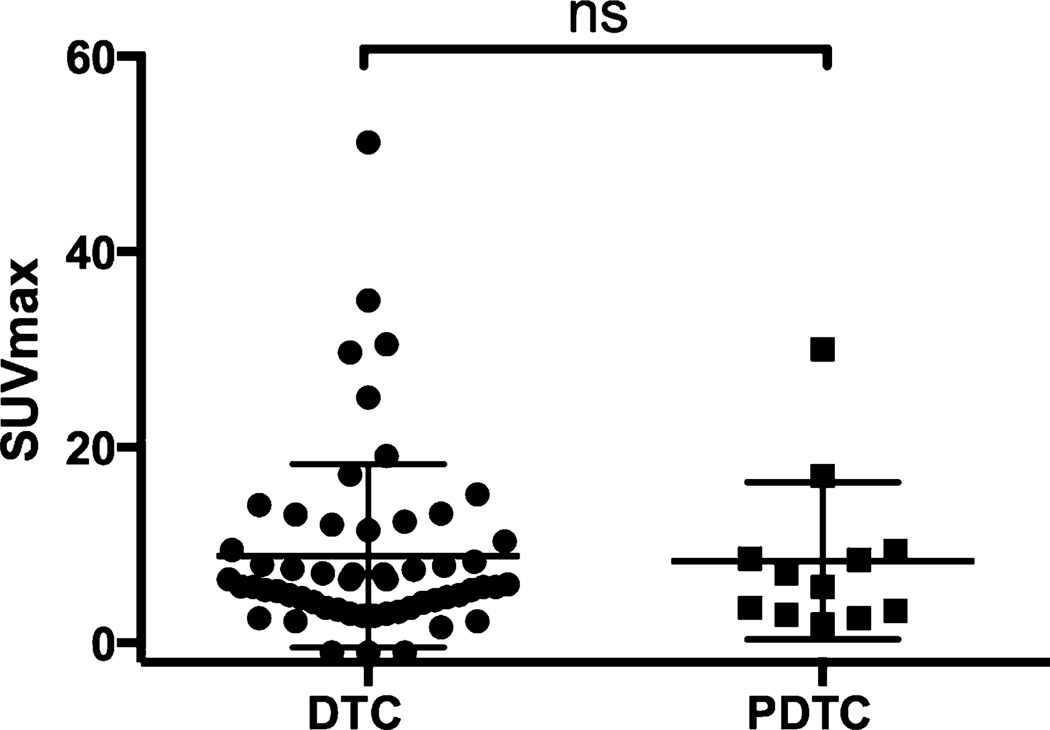

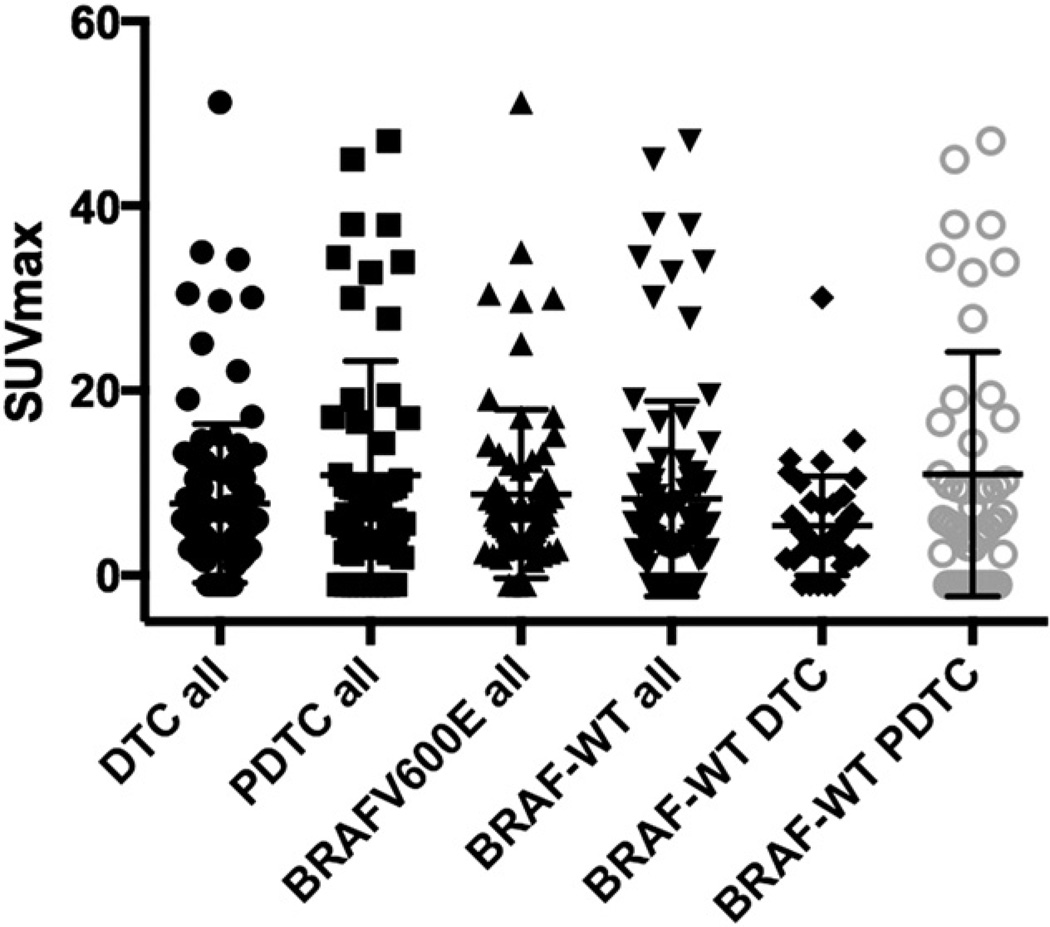

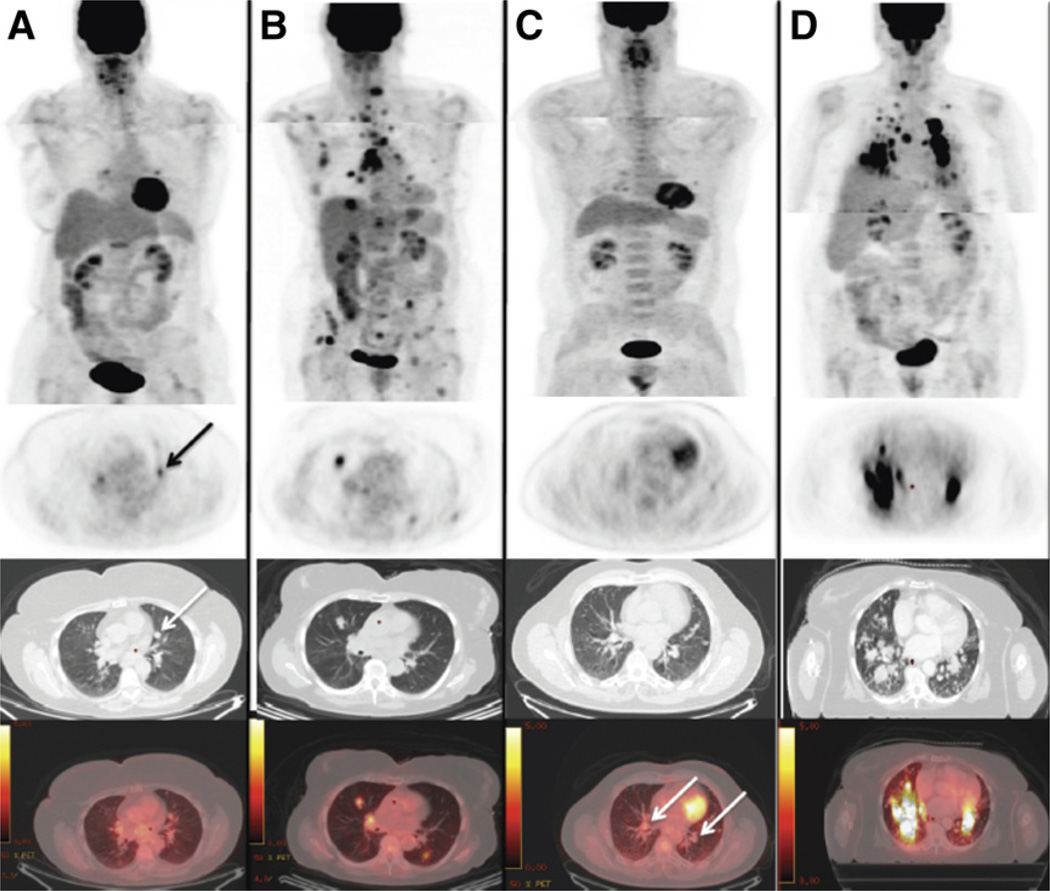

In contrast, there was no significant difference of 18F-FDG uptake in the PDTC group between BRAFV600E and BRAF-WT (P = 0.85, Mann–Whitney U test, Fig. 2). Neither did we observe a difference of SUVmax when comparing all DTC with PDTC lesions, regardless of mutational status (P = 0.90, Mann–Whitney U test, Table 3, Fig. 3). SUVmax was approximately twice as high in BRAF-WT PDTC when compared with BRAF-WT DTC (P = 0.11, Mann–Whitney U test). Patients’ images are given in Figure 4.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of SUVmax for DTC and PDTC patients harboring BRAF mutation. ns = nonsignificant. P = 0.91.

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of SUVmax for all DTC and PDTC lesions, all BRAF-positive vs. -negative lesions, and BRAF-WT DTC vs. BRAF-WT PDTC lesions. There is a difference in SUVmax distribution of BRAF-WT DTC and BRAF-WT PDTC, even though results are not significant.

FIGURE 4.

18F-FDG PET/CT scans in metastatic thyroid cancer patients with and without BRAFV600E mutations. All PET images are scaled from 0.0 to 5.0 g/mL to allow for visual comparison of 18F-FDG uptake. PET scans were acquired in 2 steps (patients’ arms raised for images of chest and arms down for images of neck) to improve image quality. (A) A 66-y-old woman harboring DTC BRAF-WT showing lung nodule (1.1 cm in diameter on CT) with low 18F-FDG uptake (arrows). (B) An 83-y-old woman harboring DTC BRAFV600E with multiple 18F-FDG–positive lesions with high uptake. (C) A 64-y-old man harboring PDTC BRAF-WT with multiple lung nodules (up to 1.5 cm in diameter on CT; arrows) with low/no 18F-FDG uptake. (D) A 75-y-old woman harboring PDTC BRAFV600E with multiple lung nodules showing high 18F-FDG uptake.

About 20% of the BRAFV600E-mutated DTC patients showed 18F-FDG uptake in the thyroid bed versus 4% in the BRAFV600E-negative group. On the other hand, 26% of the BRAFV600E-negative DTC patients showed 18F-FDG–avid metastases uptake in the skeleton versus 6% in the BRAFV600E-positive group (Table 2). There was a statistically significant difference regarding the sites’ thyroid bed (P = 0.008), lymph node (P = 0.031), and bone (P = 0.049, all Fisher exact test) between the BRAFV600E and BRAF-WT groups.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that in DTC, 18F-FDG uptake is significantly higher for tumors with BRAFV600E mutations than for tumors that are BRAF-WT. In contrast, BRAFV600E mutational status demonstrated no correlation with tumor 18F-FDG uptake in PDTC, suggesting that in this disease, glucose metabolic activity is predominantly regulated by other signaling pathways. In our cohort, the tumors were not systematically tested for mutations other than BRAFV600E, and tumors in the BRAF-WT group might harbor additional genetic defects that affect glucose metabolism.

High glucose metabolic rates of cancer cells are often explained as a consequence of proliferation: accelerated transcription and translation in proliferating cells decreases the adenosine triphosphate–to–adenosine diphosphate ratio, which causes allosteric effects on rate-limiting metabolic enzymes, thereby increasing glucose uptake. Although this explanation is widely accepted, it is at odds with the frequent clinical observation that some slowly proliferating malignancies (e.g., low-grade lymphomas) or even premalignant lesions (e.g., colonic polyps) can be highly hypermetabolic on 18F-FDG PET/CT studies (14–16).

An alternative, more recently proposed model is that activated oncogenes and inactivated tumor suppressors directly reprogram cellular metabolism. In this model, accelerated metabolic fluxes occur as a primary response to oncogenic signaling (15). This new model of tumor glucose metabolism implies that high 18F-FDG uptake in cancer cells is not necessarily the consequence of rapid proliferation but is caused by the activation of oncogenic pathways that regulate transporters and enzymes involved in the metabolism of glucose.

Although there are ample preclinical data on the relationship between oncogene activation and glucose metabolism, clinical data are relatively scarce. One approach to gain some insight into the relationship between oncogene activation and glucose metabolism in patients is to study the correlation between mutations in specific oncogenes and glucose metabolism. For instance, Parmenter et al. and Palaskas et al. showed a relationship between BRAF mutation and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase downstream targets such as cMyc and Hif-1a and increased glucose metabolism for melanoma and basallike breast cancer, respectively (12,17).

Our findings are consistent with these observations, because BRAFV600E DTCs demonstrated significantly higher 18F-FDG uptake than BRAF-negative tumors.

In patients with multiple metastatic lesions, many approaches can be used to summarize overall metabolic activity. Measuring 18F-FDG uptake of all lesions in a patient can be impractical, because thyroid cancer patients may demonstrate innumerable lung metastases that are difficult to separate on PET images. More importantly, patients with multiple metastases will skew the measured average 18F-FDG uptake. Therefore, we limited our analysis to a maximum of 1 lesion in each of the 7 prespecified body regions. We also analyzed the single lesion with the highest 18F-FDG uptake. Using both types of analyses, we found a significantly higher 18F-FDG glucose metabolic activity for DTC with a BRAFV600E mutation, suggesting that the observed differences are unlikely due to lesion selection. Patients with BRAFV600E had significantly lower thyroglobulin values than patients with BRAF-WT tumors. Thus, the higher 18F-FDG uptake of BRAFV600E tumors on PET cannot be explained by a higher tumor load.

There was no difference between the SUVmax of BRAFV600E-positive DTC and BRAFV600E-positive PTDC. The number of BRAFV600E-positive PDTC patients was quite small, limiting the strength of the statistical analysis. Interestingly, 18F-FDG uptake was approximately twice as high for BRAF-WT PDTC than for BRAF-WT DTC (Fig. 3). Consequently, we did not observe higher SUVmax for the overall group of BRAF-WT PDTC than BRAF-WT DTC.

In addition to differences in the metabolic activity of BRAFV600E DTC and BRAF-WT DTC, we also found differences in their metastatic spread. BRAFV600E-positive DTC tumors recurred more frequently to the lymph nodes and thyroid bed, whereas the BRAF-WT more often metastasized to bones, even though the number of follicular variants of the PTCs was low in both groups. This information might be helpful for the clinician when selecting specific imaging modalities for the workup of patients with rising thyroglobulin levels. In contrast, the SUV differences between BRAFV600E and BRAF-WT in DTC and PDTC were too small to limit 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging to BRAFV600E-positive tumors. Therefore, our data do not support restricting 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging to patients with PDTC.

The following limitations of our study should be noted. First, images were acquired by several PET scanners that differed in their sensitivity and spatial resolution. This difference may have contributed to the overlap of SUVs for the studied patient groups. Moreover, 53% of the lesions were smaller than 1.3 cm in diameter, and therefore partial-volume effects heavily influenced their SUVs. We could exclude a systematic difference of lesion size between the studied patient groups; nevertheless, partial-volume effects have likely contributed to the random variability of the SUV measurements.

Second, BRAFV600E status and tumor differentiation were assessed for the resected primary tumor at the time of initial diagnosis. However, in many patients, 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed several years later—accordingly, some of the tumors classified as DTCs at initial diagnosis may have evolved into PDTC. This time difference between diagnosis and PET/CT imaging may also explain some of the overlap between the analyzed patient groups, as well as the high number of bone lesions. We must also acknowledge that tumor differentiation and BRAF status may be different between the primary tumor and metastases, because only primary thyroid tumors were analyzed for mutational status and we were unable to provide histopathologic data of the metastasis. However, it is more likely that the same mutational status of the primary tumor is found in the distant metastases (18).

Additionally, a selection bias may occur, because in a clinical setting not all patients will undergo an 18F-FDG PET scan—only those who have a high-risk tumor, who exhibit clinical signs of progressive disease, or when the tumors have lost the ability to accumulate radioiodine. In our study, all of the patients were radioiodine-negative and had evidence of tumor progression state (increasing thyroglobulin values or progressive lesions in CT). Therefore, it is unlikely that the observed differences in 18F-FDG uptake between BRAF-WT and BRAFV600E tumors are related to different indications for performing the PET/CT scan. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that some of the 18F-FDG–negative lesions seen on CT represented treated disease, which may have increased the scatter of the SUV measurement in all patient groups.

CONCLUSION

In this retrospective study, BRAFV600E DTC patients show a significantly higher 18F-FDG uptake than BRAF-WT. Moreover, BRAFV600E DTC patients show a higher number of 18F-FDG–positive tumor manifestations in the thyroid bed, whereas the BRAF-WT patients show a higher number of bone metastases. The BRAFV600E mutation had no significant effect on 18F-FDG uptake in PDTC in our retrospective study, but the patient population is too small to draw definitive conclusions for this subtype of thyroid cancer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim BS, Ryu HS, Kang KH. The value of preoperative PET-CT in papillary thyroid cancer. J Int Med Res. 2013;41:445–456. doi: 10.1177/0300060513475743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim M-H, Ko SH, Bae J-S, et al. Non–FDG-avid primary papillary thyroid carcinoma may not differ from FDG-avid papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2013;23:1452–1460. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim BH, Kim S-J, Kim H, et al. Diagnostic value of metabolic tumor volume assessed by 18F-FDG PET/CT added to SUVmax for characterization of thyroid 18F-FDG incidentaloma. Nucl Med Commun. 2013;9:868–876. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328362d2d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robbins RJ, Wan Q, Grewal RK, et al. Real-time prognosis for metastatic thyroid carcinoma based on 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose-positron emission tomography scanning. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:498–505. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertagna F, Treglia G, Piccardo A, Giubbini R. Diagnostic and clinical significance of F-18-FDG-PET/CT thyroid incidentalomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3866–3875. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caronia LM, Phay JE, Shah MH. Role of BRAF in thyroid oncogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7511–7517. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimura ET, Nikiforova MN, Zhu Z, Knauf JA, Nikiforov YE, Fagin JA. High prevalence of BRAF mutations in thyroid cancer: genetic evidence for constitutive activation of the RET/PTC-RAS-BRAF signaling pathway in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1454–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grabellus F, Nagarajah J, Bockisch A, Schmid KW, Sheu S-Y. Glucose transporter 1 expression, tumor proliferation, and iodine/glucose uptake in thyroid cancer with emphasis on poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37:121–127. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182393599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soares P, Lima J, Preto A, et al. Genetic alterations in poorly differentiated and undifferentiated thyroid carcinomas. Curr Genomics. 2011;12:609–617. doi: 10.2174/138920211798120853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grabellus F, Worm K, Schmid KW, Sheu S-Y. The BRAFV600E mutation in papillary thyroid carcinoma is associated with glucose transporter 1 overexpression. Thyroid. 2012;22:377–382. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xing M, Alzahrani AS, Carson KA, et al. Association between BRAF V600E mutation and mortality in patients with papillary thyroid cancer. JAMA. 2013;309:1493–1501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parmenter TJ, Kleinschmidt M, Kinross KM, et al. Response of BRAF-mutant melanoma to BRAF inhibition is mediated by a network of transcriptional regulators of glycolysis. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:423–433. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yun J, Rago C, Cheong I, et al. Glucose deprivation contributes to the development of KRAS pathway mutations in tumor cells. Science. 2009;325:1555–1559. doi: 10.1126/science.1174229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schöder H, Noy A, Gönen M, et al. Intensity of 18fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in positron emission tomography distinguishes between indolent and aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4643–4651. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward PS, Thompson CB. Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even Warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Israel O, Yefremov N, Bar-Shalom R, et al. PET/CT detection of unexpected gastrointestinal foci of 18F-FDG uptake: incidence, localization patterns, and clinical significance. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:758–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palaskas N, Larson SM, Schultz N, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxy-glucose positron emission tomography marks MYC-overexpressing human basal-like breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5164–5174. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ricarte-Filho JC, Ryder M, Chitale DA, et al. Mutational profile of advanced primary and metastatic radioactive iodine-refractory thyroid cancers reveals distinct pathogenetic roles for BRAF, PIK3CA, and AKT1. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4885–4893. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]