Abstract

AIM: To investigate roles of genetic polymorphisms in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) onset, severity, and outcome through systematic literature review.

METHODS: The authors conducted both systematic and specific searches of PubMed through December 2015 with special emphasis on more recent data (from 2012 onward) while still drawing from more historical data for background. We identified several specific genetic polymorphisms that have been most researched and, at this time, appear to have the greatest clinical significance on NAFLD and similar hepatic diseases. These were further investigated to assess their specific effects on disease onset and progression and the mechanisms by which these effects occur.

RESULTS: We focus particularly on genetic polymorphisms of the following genes: PNPLA3, particularly the p. I148M variant, TM6SF2, particularly the p. E167K variant, and on variants in FTO, LIPA, IFNλ4, and iron metabolism, specifically focusing on HFE, and HMOX-1. We discuss the effect of these genetic variations and their resultant protein variants on the onset of fatty liver disease and its severity, including the effect on likelihood of progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. While our principal focus is on NAFLD, we also discuss briefly effects of some of the variants on development and severity of other hepatic diseases, including hepatitis C and alcoholic liver disease. These results are briefly discussed in terms of clinical application and future potential for personalized medicine.

CONCLUSION: Polymorphisms and genetic factors of several genes contribute to NAFLD and its end results. These genes hold keys to future improvements in diagnosis and management.

Keywords: Genetic polymorphisms, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, PNPLA3, TM6SF2, FTO, Cirrhosis, Iron metabolism

Core tip: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is reaching epidemic proportions not only in the United States but worldwide. Its end results can include non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Studies since 2008 have demonstrated and continue to uncover noteworthy genetic factors that influence NAFLD and its onset, severity, and ultimate outcome. Awareness of these genetic elements yields improved understanding of the pathology of the disease and will likely be key to individualizing effective patient therapy in the near future.

INTRODUCTION

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome[1-4]. Its already-high worldwide prevalence continues to grow[2,5,6]. Its pathogenesis is related to environmental, dietary, and host factors; chiefly to increasing obesity and sedentary lifestyles[7-9]. Evidence also points to genetic factors playing important roles in modulating the occurrence, severity, and long-term prognosis of NAFLD. It is important for practicing gastroenterologists to be aware of major genetic factors that influence NAFLD and its progression because they hold the key to better understanding of pathogenesis and new and better treatments. In this review, we describe and highlight the most important of these genetic influences. Table 1 summarizes the genes and variants discussed in our review.

Table 1.

Genes and variants emphasized in this review

| Gene name | Genetic variant | Coding DNA change | Amino acid change | Putative effect of variant |

| PNPLA3 | rs738409 | 444C>G | I148M | Increased hepatocyte triglyceride content |

| rs6006460 | 1531G>T | S453I | Lower-than-average hepatic triglyceride accumulation | |

| TM6SF2 | rs58542926 | 499A>G | E167K | Elevated AST/ALT, increased hepatic triglyceride levels, decreased serum cholesterol |

| rs10401969 | 613+80A>G | Intron | Lower hepatic TM6SF2 mRNA levels correlate with larger hepatocellular lipid droplets | |

| LIPA | rs116928232 | 894G>A | E8SJM | Cholesterol ester storage disease often resulting in fibrosis→cirrhosis |

| IFNλ4 | rs12979860 | 151-152G>A | Intron | Increased degree of hepatic inflammation and fibrosis |

| HFE | rs1800562 | 845G>A | C282Y | Increased hepatic iron uptake, associated with greater NAFLD risk/severity |

| rs1799945 | 187C>G | H63D | Increased hepatic iron uptake, associated with greater NAFLD risk/severity | |

| HMOX1 | rs2071746 | -413A>T | Affects promoter | Higher HMOX1 activity correlated with less frequent and less severe NAFLD |

| FTO | rs1421085 | 46-43098T>C | Affects repressor | Adipocytic phenotype shift from beige (energy-dissipating) to white (energy-storing) |

| GNPAT | rs11558492 | 1556A>G | D519G | Worsened iron overload in patients with HFE |

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy and study selection

We conducted a search in PubMed to identify relevant articles published from January 1, 2012 to December 2015. The search terms (NASH OR NAFLD) AND genetic* yielded 1,481 published references. Filtering for human studies yielded 853; also filtering for English yielded 819. Another search approach using the MeSH terms “Fatty Liver/genetics”[Mesh] for the same time frame yielded 801 published references. Filtering for human studies yielded 539; also filtering for English yielded 511.

The two searches were combined with duplicates eliminated, leaving 997 references, which were sorted by the authors according to subject relevance, leaving 111. After careful evaluation, the 45 recent references which proved most important and relevant are cited in this article.

Searches for major background and findings/publications prior to January 2012 yielded 44 additional citations. Further, each author performed independent searches based on specific keywords and search terms that did not completely intersect with the overall search. This yielded an additional 29 sources cited. Finally, 35 additional citations were incorporated with adaptation of Table 2.

Table 2.

Variation in frequency of the common PNPLA3 polymorphism in different regions and among different ethnic groups

| Descent/ethnicity | Alleles C1 | Alleles G2 | Genotypes C|C | Genotypes C|G | Genotypes G|G |

Allele count |

Genotype count |

|||

| C allele | G allele | C|C | C|G | G|G | ||||||

| All (n = 2504) | 73.8% | 26.2% | 56.9% | 33.8% | 9.3% | 3695 | 1313 | 1424 | 847 | 233 |

| African (n = 661) | 88.2% | 11.8% | 78.8% | 18.8% | 2.4% | 1166 | 156 | 521 | 124 | 16 |

| Latin American (n = 347) | 51.6% | 48.4% | 27.7% | 47.8% | 24.5% | 358 | 336 | 96 | 166 | 85 |

| Asian (n = 504) | 65.0% | 35.0% | 44.0% | 41.9% | 14.1% | 655 | 353 | 222 | 211 | 71 |

| European (n = 503) | 77.4% | 22.6% | 60.2% | 34.4% | 5.4% | 779 | 227 | 303 | 173 | 27 |

| Southern Asian (n = 489) | 75.4% | 24.6% | 57.7% | 35.4% | 7.0% | 737 | 241 | 282 | 173 | 34 |

Allele C: Wild type;

Allele G: Variant rs738409, codes I148M protein.

RESULTS

PNPLA3

Function of PNPLA3: Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3, also called adiponutrin) is a 481-amino acid protein expressed to greatest degree in hepatocytes[10]. It functions as both a triglyceride hydrolase (suggesting catabolic lipase activity) and acetyl-CoA-independent transacylase (suggesting anabolic lipogenic activity)[11-13].

The most commonly studied variant of PNPLA3 is rs738409, altering wild-type cytosine to guanine at nt444 (c.444C>G), which changes isoleucine to methionine at residue 148 (p. I148M). This SNP is associated with increased hepatocellular triglyceride accumulation (up to two-fold greater than wild type[14,15]) and the development of NAFLD[16].

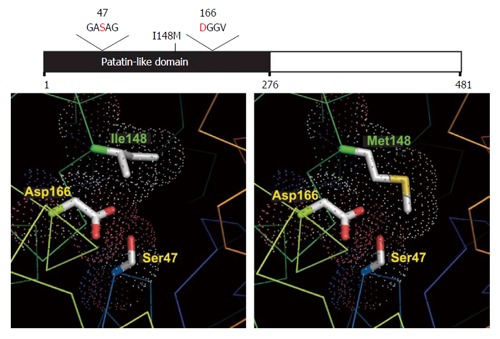

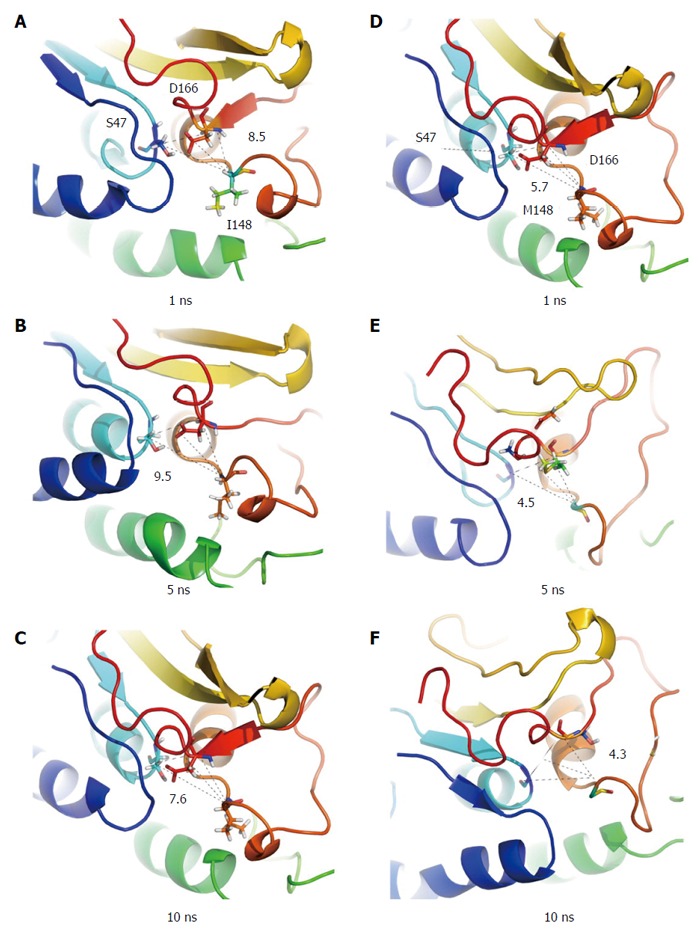

I148M increases hepatocellular lipid retention by altering enzymatic hydrolysis of emulsified triglycerides. The long side chain of the methionine substitution at p.148 restricts substrate access to the enzyme’s catalytic site[17,18] despite the functional catalytic dyad (Figures 1 and 2). The defunct I148M protein accumulates on hepatic lipid droplets, preventing other lipolytic elements from accessing the coated droplet and rendering it metabolically inaccessible[19].

Figure 1.

Structural models of wild type and mutant PNPLA3. Structural models of normal (Ile148) and mutant (Met148, associated with increased hepatic triglyceride content) PNPLA3 are shown in the left and right panels, respectively. This change effectively blocks substrate access to the catalytic dyad seen at Ser47 and Asp166. Adapted from He et al[8] used under Creative Commons-BY licensing.

Figure 2.

Structural snapshots of wild type and mutant PNPLA3 in substrate-free systems. Subplots A-C present conformations of the wild type protein at 1, 5, 10 ns, respectively, while D-F present the I148M mutant. From Xin et al[18] with permission of the copyright holder.

I148M subjects have lower hepatic VLDL secretion than wild-type homozygotes with the same degree of steatosis. In vitro correlation showed a lower degree of apoB-containing lipoprotein secretion from I148M cells[20].

The I148M variant leads to lower levels of circulating adiponectin[21], associated with susceptibility to NAFLD[22]. Adiponectin has anti-inflammatory effects[23]; reduced levels may allow inflammation leading to progression from NAFLD into NASH[24]. Adiponectin may also inhibit activation of pro-fibrotic hepatic stellate cells[25].

PNPLA3 I148M as ethnic NAFLD risk factor: Many of the studies previously cited were conducted on patients of Caucasian descent. The presence of rs738409 G, however, has been shown to be strongly associated with susceptibility to NAFLD and degree of steatosis across many ethnic groups. Several studies indicate that the rs738409 GG genotype is associated with development and progression of NAFLD in Asian cohorts, including Chinese[26,27], Japanese[28], Korean[29], and Indian[30,31] populations.

The 1000 Genomes consortium has found significant ethnic variability in the prevalence of rs738409 (Table 3)[32]. The Latin American cohort is particularly noteworthy. Persons of Hispanic descent have been found to have higher prevalence of hepatic steatosis (45%) than both white (33%) and black (24%) subjects[33]. A study of cryptogenic cirrhosis (most often caused by NASH) showed that, despite similar prevalence of diabetes between patients of Hispanic and African heritages, the prevalence of cryptogenic cirrhosis in Hispanics is 3.1-fold higher than among Caucasian subjects, and the prevalence among persons of African origin was 3.9-fold lower than among Caucasians[34]. In Hispanic populations, variation in PNPLA3 was found to affect not only the degree of liver fat content[35] but also serum aminotransferase elevations[36].

Table 3.

Summary of genetic modifiers of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

| Gene | Protein | Study details and comments |

| Glucose metabolism and insulin resistance | ||

| ENPP1; IRS1 | Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase family member 1; insulin receptor substrate 1 | Functional variants promote insulin resistance by impairing insulin receptor signaling[114,115]. Carriage of nonsynonymous SNPs in ENPP1 (rs1044498, encoding Lys121Gln) and IRS1 (rs1801278, encoding Gln972Arg) reduced AKT activation, promoted insulin resistance, and showed independent association with greater fibrosis[116] |

| GCKR | Glucokinase regulatory protein | GCKR SNP rs780094 has been associated with hepatic TG accumulation[117] and greater NAFLD fibrosis[118] |

| PPARG | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ | A loss-of-function SNP (rs1805192, encoding Pro12Ala) impairs transcriptional activation and affects insulin sensitivity[119] |

| SLC2A1 | Solute carrier family 2, facilitated glucose transporter member 1 | Variants in SCLA1 are associated with NAFLD independent of insulin resistance or T2DM[120] |

| Downregulation of SLC2A1 in vitro promoted lipid accumulation and increased oxidative stress, potentially linking the key pathogenic features of NAFLD: oxidative injury and increased lipid storage | ||

| Steatosis: Hepatic lipid import or synthesis | ||

| FTO | Fat mass and obesity-associated protein | SNP rs1421085 (c.46-43098T>C) disrupts a conserved motif, which leads to de-repression of a potent preadipocyte enhancer and to a shift in phenotype from energy-dissipating beige adipocytes to energy-storing white adipocytes, with reduction in mitochondrial thermogenesis[70] |

| LPIN1 | Phosphatidate phosphatase LPIN1 | Required for adipogenesis and the normal metabolic flux between adipose tissue and liver; also acts to regulate fatty acid metabolism[121,122] |

| Variants have been associated with multiple components of the metabolic syndrome[121,123] | ||

| SLC27A5 | Very long chain acyl-CoA synthetase | Silencing Slc27a5 reverses diet-induced NAFLD and improves hyperglycemia in mice[124] |

| Carriage of the SLC27A5 rs56225452 polymorphism has been associated with higher ALT and greater postprandial insulin and triglyceride levels[124] | ||

| In patients with histologically proven NAFLD, the effect of BMI on degree of steatosis differed with SLC27A5 genotype[125] | ||

| Steatosis: Hepatic lipid export or oxidation in steatosis | ||

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E | Plasma protein involved in lipid transport and metabolism[126]. Three alleles (ε2, ε3, and ε4) determine three isoforms (ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4) resulting in six ApoE genotypes (E2/2, E3/3, E4/4, E2/3, E2/4, E3/4). Overall homozygosity for the ε2 allele in one study was associated with dyslipidemia, but not NAFLD[127] |

| In a subgroup of non-obese individuals, the ε2 allele and the E2/3 genotype were more prevalent in controls, suggesting it might be protective[127]. Consistent with this result, the E3/3 genotype was associated with NASH in a Turkish cohort, whereas E3/4 was protective[128] | ||

| LEPR | Human leptin receptor | SNP rs1805096 (c.3057G>A) may contribute to the onset of NAFLD via regulation of lipid metabolism[129]. Combination of either of LEPR SNPs rs1137100 or rs1137101 with PNPLA3 rs738409 exacerbates risk of developing NAFLD more than either of the variants on its own[130] |

| NR1I2 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group I member 2 (also known as pregnane X receptor) | NR1I2 encodes a transcription factor that regulates hepatic detoxification and acts through CD36 (fatty-acid translocase) and various lipogenic enzymes to control lipid metabolism[131] |

| Nr1i2-deficient mice develop steatosis[131] | ||

| Two SNPs (rs7643645 and rs2461823) were associated with NAFLD and were also a predictor of disease severity[132] | ||

| PNPLA3 | Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 | The nonsynonymous c.444C>G nucleotide transversion mutation SNP (rs738409, encoding p.I148M) has been consistently associated with steatosis, steatohepatitis, and hepatic fibrosis. Function remains incompletely understood[39,42] |

| PPARα | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α | PPAR-α is a molecular sensor for long chain fatty acids, eicosanoids, and fibrates[133]; activated by increased hepatocyte fatty-acid load, it limits TAG accumulation by increasing fatty acid oxidation |

| Carriage of a non-synonymous SNP (rs1800234, encoding p. V227A) increases activity, and was associated with NAFLD despite reduced BMI[134,135] | ||

| A loss-of-function polymorphism (rs1800206, encoding p. L162V) was not associated with NAFLD[136] | ||

| TM6SF2 | Transmembrane 6 super family 2 | The TM6SF2 rs58542926 minor allele is associated with greater steatosis, steatohepatitis, and NAFLD fibrosis. The major allele is associated with dyslipidemia and greater CVD risk[61,66,68,69] |

| Steatohepatitis: Oxidative stress | ||

| ABCC2 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily C (CFTR/MRP), member 2 | Association studies support a role for ABCC2 (also known as MRP2), which facilitates terminal excretion and detoxification of endogenous and xenobiotic organic anions, including lipid peroxidation products[137] |

| GCLC; GCLM | Glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic unit; glutamate-cysteine ligase regulatory unit | Glutamate-cysteine ligase is the rate-controlling step in glutathione synthesis; absence of the Gclc gene causes steatosis and liver failure in mice[138] |

| A study of 131 patients with NFLD reported the GCLC promoter region polymorphism (c. c-129t, rs17883901) was associated with steatohepatitis compared with simple steatosis[139] | ||

| HFE | Hereditary hemochromatosis protein | Hepatic iron accumulation promotes oxidative stress. Two studies, examining 177 patients, reported carriage of an HFE polymorphism (rs1800562) that was associated with more severe steatohepatitis and advanced fibrosis[95,140] |

| However, three other studies have not shown increased carriage of either the C282Y or H63D (rs1799945) mutations[105-107]. Meta-analysis have also provided conflicting results[108,109] | ||

| SOD2 | Superoxide dismutase [Mn], mitochondrial | Carriage of the nonsynonymous SNP rs4880 has been associated with advanced hepatic fibrosis in NAFLD in both Japanese[141] and European[142] cohorts |

| Endotoxin response | ||

| CD14 | Monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 | A lipopolysaccharide receptor expressed on monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils that enhances TLR4 endotoxin signaling. An association with promoter-region polymorphism rs2569190 increasing CD14 expression has been reported[143] |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 | Study of a spontaneous Tlr4 null mutation in C3H/J mice has established the contribution of TLR4/endotoxin to NAFLD pathogenesis in the laboratory[144] |

| TLR4 polymorphisms rs4986791 and rs4986790 influence hepatitis-C-related fibrosis[145,146], but no association with NAFLD and TLR4 variants has been found | ||

| Cytokines | ||

| IFNλ4 | Interferon lambda 4 | The intronic rs12979860 SNP in IFNλ4 is a strong predictor of fibrosis in an etiology-independent manner, including a cohort of 488 NAFLD cases. Those with rs12979860 cc had greater hepatic inflammation and fibrosis[85] |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor | A promoter polymorphism (c.238G>A) has been associated with NASH[147,148] suggesting a primary role in the transition from steatosis to steatohepatitis. A separate study found that two other promoter region polymorphisms (rs1799964 and rs1800630) were more common in NAFLD than a control population[148] |

| Fibrosis | ||

| AGTR1 | Type-1 angiotensin II receptor | Studies link SNP rs3772622 with grade of steatohepatitis and stage of fibrosis; the most recent study also suggests an interaction with PNPLA3 genotype[149,150] |

| KLF6 | Kruppel-like factor 6 | SNP rs3750861 has been associated with milder NAFLD-related hepatic fibrosis in three separate European cohorts[151] |

| MERTK | Myeloid epithelial reproductive tyrosine kinase | Homozygosity for common non-coding rs4374383 G>A polymorphism associated with less fibrosis in hepatitis C and NAFLD. Mechanism suggested is modulation of HSC activation[152] |

Adapted from Anstee and Day[153] with permission of copyright holder.

Specifically among Hispanic patients, Mexican Americans studied by 1000 Genomes were found to have 34.4% of GG GG genotypes and 42.2% CG genotypes. It is unsurprising, then, that subjects of Mexican descent were recently found to have higher prevalence of NAFLD than any other group of Hispanic descent[37].

For African Americans, the rs738409 mutation has been found to contribute to the risk of increased hepatic steatosis[38]. However, another mutation of PNPLA3 found in the African American population (rs6006460, c.1531G>T, encoding p.S453I) showed association with lower-than-average hepatic fat content[39]. This gene has a minor allele frequency of 10.4% in African American patients, but only 0.3% in Caucasians and 0.8% in Hispanics.

Effect on severity of disease

Fibrosis: Fibrosis is increased in I148M subjects[40,41], possibly resulting from increased inflammation due to increased hepatic steatosis. It has been suggested that there may also be a directly pathogenic mechanism to the variant[42], perhaps via fibrogenesis, as I148M is associated with increased fibrosis independent of its effect on hepatocyte lipid content[43].

Cirrhosis: Presence of c.444C>G (both homozygous GG and heterozygous CG) was associated with significantly increased risk of cirrhosis when compared to wild type[44], regardless of etiology.

Hepatocellular carcinoma: Occurrence of HCC is more common in homozygous I148M patients than in wild type patients (OR = 1.76)[45-47]. I148M patients have more than double the risk for Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (adjusted OR = 2.26) for each variant allele[48]. It is unknown if the mutation is directly oncogenic.

Role in progression of other hepatic diseases: Although beyond the scope of this review, it is worthy of mention that I148M is positively correlated with increased susceptibility, progression, and/or severity in alcoholic liver disease[49-51], chronic hepatitis C[52-55], chronic hepatitis B[56,57], hemochromatosis[58], and Wilson disease[59]. So broad is the effect of I148M on hepatic disease, it has been elsewhere suggested as the defining criterion of so-called PNPLA3-associated steatohepatitis, or “PASH”[60].

Transmembrane 6 superfamily 2

Transmembrane 6 Superfamily 2 (TM6SF2), also known as KIAA 1926, is a protein of unknown function with 377 amino acids and molecular mass of 42.6 kDa. The chromosomal location of the TM6SF2 gene in humans is 19p13.11. It has broad tissue and organ expression with highest relative levels of expression in the small intestine and liver[61-63].

TM6SF2 as NAFLD risk

One variant in TM6SF2 (rs10401969, c.613+80A>G) is associated with reduced hepatic mRNA levels of TM6SF2[64]. Decreased levels correlated with altered expression of multiple genes involved in triglyceride synthesis (ACSS2, DGAT1, DGAT2, and PNPLA3) and with increased size and number of hepatocytic lipid droplets, but with no effect on cell damage and proliferation.

Murine hepatocyte-specific silencing of Tm6sf2 resulted in decreased levels of plasma triglycerides, LDL, HDL, and triglyceride content of VLDL with a threefold increase in hepatic triglyceride levels. Overexpression of the gene, on the other hand, was associated with a reduction in the number and size of the hepatocytic lipid droplets.

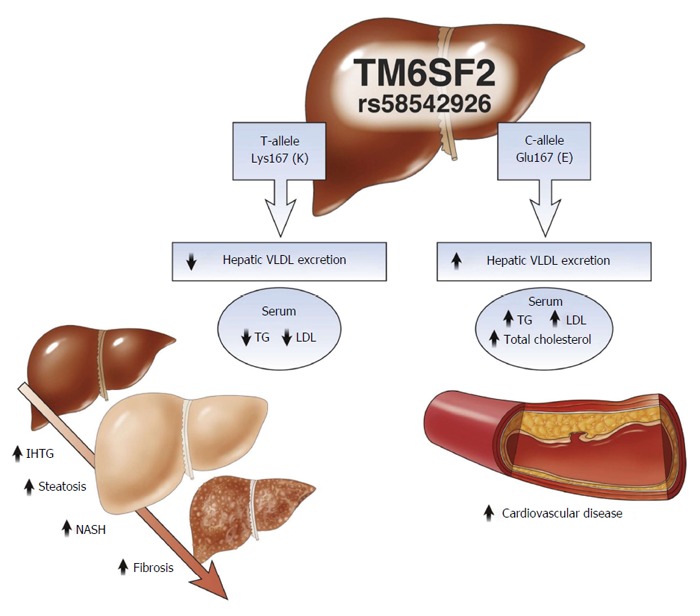

Another TM6SF2 SNP (rs58542926, c.499G>A), changes glutamic acid to lysine amino acid at protein residue 167 (p. E167K). Presence of this variant was positively associated with associated with elevations in serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT)[61] and with the development of NASH compared to wild type patients[65]. It was also associated with lower levels of plasma triglyceride and cholesterol. These were concomitant with increases in the hepatic triglyceride levels[66]. Impaired TM6SF2, then, increases the likelihood of NAFLD development while decreasing the likelihood of hypertriglyceridemia and vascular diseases associated with cardiovascular disease, making variation in TM6SF2 a two-edged sword (Figure 3)[67,68].

Figure 3.

Effects of TM6SF2 genetic variations. TM6SF2 plays a role in VLDL export from liver to serum which results in increased serum lipids and myocardial infarction, and decreased risk of liver steatosis. From Kahali et al[67], used by permission of the copyright holder. Chol: Cholesterol; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IHTG: Intrahepatic triglyceride; NASH: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; TG: Triglyceride; VLDL: Very low-density lipoprotein.

Effect of TM6SF2 on disease

TM6SF2 rs58542926 variant was strongly associated with NAFLD, advanced fibrosis, and cirrhosis[69], independent of age, body mass index (BMI), type 2 diabetes mellitus and PNPLA3 rs738409 genotype. It remains unclear if the minor allele is associated with increased risk of HCC.

Fat mass and obesity-related gene

The fat mass and obesity-associated gene (FTO) encodes a nuclear protein of 506 amino acids with molecular mass 58.3 kDa that functions as a Fe2+-containing and requiring oxygenase that repairs alkyl DNA and RNA by carrying out oxidative demethylations, especially of N(6) methyladenosine residues on RNA, the most prevalent internal modification of mRNA in higher eukaryotes.

A recent landmark study[70] showed that the single nucleotide variant rs1421085 (c.46-43098T>C) of the FTO gene disrupts a conserved motif that is essential for expression of the repressor AT-rich interactive domain 5B (ARID5B), which, in turn, leads to de-repression of a potent preadipocyte enhancer and to doubling of Iroquois homeobox 3 and 5 (IRX3 and IRX 5) expression during early adipocyte differentiation. This shifts the adipocyte phenotype from energy-dissipating beige to energy-storing white, with a five-fold reduction in mitochondrial thermogenesis.

Down-regulation of Irx3 in murine adipose tissue reduced body weight and increased heat production without changes in appetite or exercise. Repair of the ARID5B motif of rs1421085 in primary adipocytes from a patient with the C [risk] allele activated gene expression profiles of brown fat and increased thermogenesis seven-fold.

Thus, this single gain-of-function variant in a non-coding region of FTO plays a dominant role in BMI set point and possibly in NAFLD and NASH as well. It can be hoped that pharmacologic or other approaches, such as gene editing to restore activity of ARID5B and/or to down-regulate IRX3 and IRX5, will prove to have pronounced anti-obesity and anti-NAFLD/NASH effects.

LIPA gene (lipase A, lysosomal acid, cholesterol esterase)

The lysosomal acid lipase A gene (LIPA) is located on human chromosome 10q23.31[71,72]. LIPA produces and regulates lysosomal acid lipase (LIPA), also known as cholesterol ester hydrolase. LIPA contains 399 amino acids and has molecular mass of 45.4 kDa. It catalyzes lysosomal hydrolysis of cholesteryl esters and triglycerides, which plays a pivotal role in the intracellular regulation of the endogenous cholesterol synthesis, uptake of low density lipoproteins (LDL) and cholesterol esterification[73,74].

At least six splice variants of LIPA have been described. Some mutations lead to reduced or absent production of the LIPA enzyme, yielding increased cholesterol ester storage in the lysosomes. Defective LIPA gene inherited as autosomal recessive disorder is clinically known as Wolman’s disease (fatal in infancy)[75,76] and cholesterol ester storage disease (CESD, presenting later in life with dyslipidemia[77,78], premature atherosclerosis[79], and cirrhosis[80]). The majority of mutations (42%) are due to deletions/insertions; the remainder are splice-site and missense mutations[81]. The most common mutation is a splice-site at the exon 8, E8SJM (rs116928232, c.894G>A).

Fibrosis leading to cirrhosis and its complications is seen in two-thirds of patients with LIPA deficiency[82]. Of LIPA enzyme deficiency patients[80], 64% had fibrosis and/or cirrhosis, with cirrhosis present in 29% of patients. LIPA mutations have not been associated with increased risk of HCC.

Interferon λ 4 gene

IFN Interferon λ 4 gene (IFNλ4)4 codes for a cytokine product thought to trigger antiviral responses, especially to HCV, by activating the JAK-STAT pathway and up-regulating selected interferon-responsive genes. The gene is widely expressed in nearly all tissues. SNPs rs12979860 and rs8099917 are located within intron 1 region of the IFNλ4 gene on chromosome 19q13.2. These polymorphisms control the inflammatory and immune response pathways[83,84] which form the basis for the interferon-based treatment of HCV.

A recent study involving 4,172 patients with liver disease (chronic HCV, chronic HBV, and NAFLD) found that patients with rs12979860 have greater hepatic inflammation and fibrosis[85]. The exact mechanism for this is unclear. It is thought that NAFLD leads to higher basal interferon stimulated genes, leading to immune activation and cell death.

Genes and proteins of iron and heme metabolism

Hepatic iron toxicity is chiefly related to the role of iron in catalyzing oxidation reactions with formation of the highly reactive and toxic hydroxyl free radical[86]. Insertion of iron into protoporphyrin forms heme, which is also highly reactive and capable of increasing oxidative stress[87]. Thus, genetic variations in genes and proteins involved in iron and heme metabolism may influence NAFLD/NASH, as well as other liver diseases[74-80].

Heavy iron overload, such as occurs in hemochromatosis, is known to lead to hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis and HCC[88]. Modest amounts of hepatic iron - which of themselves would not produce toxicity - can enhance or synergize hepatotoxicity in chronic viral hepatitis and/or alcoholic and NAFLD[89-92]. Increased levels of serum ferritin are associated with higher severity and stage of fibrosis in NAFLD[93] and with all-cause mortality and with morbidity and mortality[94].

The major (C282Y) and minor (H63D) mutations of HFE are risk factors for NAFLD and for more severe disease[95-97]. The most important additional modulating factors are chronic HCV infection and heavy alcohol use. However, other genetic factors, such as genetic variation in one or more of the many other genes involved in iron metabolism (e.g., BMP2, FPN, FTL, HAMP, HJV and others[98,99]) also play a role. Recently, a genetic variation in GNPAT (rs11558492, c. 1556A>G, exon 11; chromosome 1q42; p.D519G) was reported to be significantly associated with more severe iron overload in male subjects homozygous for C282Y, the major mutation of HFE[100]. The mechanism for the effect is suggested to relate to an effect of deficient GNPAT to down-regulate hepcidin production.

The above observations led to the idea that iron reduction accomplished by therapeutic phlebotomies might be of benefit in the metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, and NAFLD. Several studies have shown that phlebotomies to near iron-depletion (serum ferritin levels about 25 ng/mL), but short of anemia, lead to improvements in insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance[101,102], and that chronically sustained iron reduction leads to lower serum ALT/AST, less necro-inflammation, and less fibrosis[103]. A recently published exception is that of Adams et al[104], although the trend of data in this paper also favored the iron reduction cohort. Lesser effectiveness in this work may relate to the shorter duration of study (6 vs 18-36 mo); longer duration of iron reduction therapy is probably important for study endpoints such as progression of hepatic fibrosis/cirrhosis and development of HCC.

Other studies did not show increased frequency of carriage of HFE mutations in patients with NAFLD than in controls[105-107]. Meta-analyses have also yielded divergent results[108,109]. Thus, the role of HFE mutations in modulating NAFLD is not entirely settled. Some of the reason for this may be that other genetic, dietary, and environmental influences, in addition to HFE, materially affect iron loading in the liver and probably also in other tissues.

Heme oxygenases (HMOX1, HMOX2) are key cytoprotective enzymes, protecting the liver and other organs from oxidative stress caused by excess heme, potentially a stronger pro-oxidant than iron[87]. HMOX1 is especially important, as it is highly inducible by heme, heavy metals, oxidative stress, and other forms of chemical or physical stress.

Levels of expression of the HMOX1 gene are also under genetic control in two major ways: the variable length of GT repeats in the promoter and a functional SNP at position -413 upstream of the transcription starting point (c.-413A>T; rs2071746). Shorter GTn repeats [18-22 nts] and -413A are associated with higher levels of HMOX1 gene expression and higher HMOX1 activities. Higher levels of expression of HMOX1 have been correlated with less frequent and less severe NAFLD/NASH in rodents and humans[110-112].

Results on balance indicate that even modest increases in iron or heme are potentially hepatotoxic, especially in the presence of chronic hepatitis C or the metabolic syndrome. Until more effective treatments become available for NAFLD, iron reduction remains a safe and reasonable therapeutic modality, recent suggestions to the contrary notwithstanding[113].

COMMENTS

Background

The worldwide prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is increasing rapidly, related to multiple causes, some better understood than others. Delving into the genetic underpinnings of NAFLD development and severity is helping us not only to understand better genetic risk factors of NAFLD, but also, by assessing the effects of the genes and proteins involved, we learn more about the pathogenesis and management of the disease itself. The primary aim of this review is to discuss the known major genetic factors that influence NAFLD and to improve awareness and understanding of these factors among physicians and other healthcare providers.

Research frontiers

The prevalence of NAFLD is likely to continue to increase with the worldwide expansion of “Western diets” and sedentary lifestyles pari passu with trends toward more frequent and more severe obesity. The number of genetic polymorphisms that predispose a patient to NAFLD or worsen an affected patient’s prognosis, however, is also likely to continue expanding. Indeed, we continue to identify additional genetic factors and associations with NAFLD and the metabolic syndrome. It is likely that this will, at some point in the near future, allow us to predict, warn about, and ideally prevent disease before it occurs.

Innovations and breakthroughs

As the author develop a better understanding of the genetic underpinnings of fatty liver disease and its progression, they will likely gain insight not only into the origins and physiological basis of this problem, but also into how they can better combat it. They foresee in the near future development and validation of a panel of genetic tests that will identify subjects at higher or lower risk of development and progression of NAFLD and that will identify subjects for therapies targeted specifically to specific patient genotypes. Regardless of favorable or adverse genetic factors, however, for the foreseeable future the author will need to continue counseling all their patients about the benefits of exercise and sensible diets, consumed in moderation.

Applications

There have already been therapeutic trials of iron reduction for therapy of NAFLD/NASH; such therapy is likely to be more necessary and effective in subjects with mutations in HFE, GNPAT, and other genes that tend to increase hepatic iron levels. Genetic testing for the variants discussed above and others yet to be discovered may ultimately be used to assess individual risk of hepatic disease and may direct early detection and prophylactic treatment in patients at risk. Similarly, although less studied thus far, genetic variations in PNPLA3 and/or TM6SF2 may be expected to influence efficacy of other therapies and allow for greater individualization of therapy. It will be of increasing value and importance going forward to know and to take into account host genotypes in both observational and interventional studies in NAFLD/NASH.

Terminology

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, or NAFLD, is the most common form of chronic liver disease in the United States and continues to increase in prevalence around the world. It is caused by increased intrahepatic accumulation of fatty deposition in the liver (steatosis) and can progress from a largely benign condition to inflammatory hepatitis (NASH), to cirrhosis and beyond. NAFLD is now usually diagnosed based upon history, physical examination, and hepatic imaging. Diagnosis of NASH requires liver biopsy; staging of severity of fibrosis is being done with increasing frequency by assessment of hepatic stiffness by elastography, although liver biopsy remains the gold standard.

Peer-review

This article is informative and presented in a systematic way. Well written and will be of use to the readership.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: February 10, 2016

First decision: March 7, 2016

Article in press: May 23, 2016

P- Reviewer: Ajith TA, Chetty R, Kaya M S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Abd El-Kader SM, El-Den Ashmawy EM. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: The diagnosis and management. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:846–858. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i6.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Diehl AM, Brunt EM, Cusi K, Charlton M, Sanyal AJ. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:811–826. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, Forlani G, Cerrelli F, Lenzi M, Manini R, Natale S, Vanni E, Villanova N, Melchionda N, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and the metabolic syndrome. Hepatology. 2003;37:917–923. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Takeda N, Nakagawa T, Taniguchi H, Fujii K, Omatsu T, Nakajima T, Sarui H, Shimazaki M, et al. The metabolic syndrome as a predictor of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:722–728. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazo M, Hernaez R, Eberhardt MS, Bonekamp S, Kamel I, Guallar E, Koteish A, Brancati FL, Clark JM. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:38–45. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.López-Velázquez JA, Silva-Vidal KV, Ponciano-Rodríguez G, Chávez-Tapia NC, Arrese M, Uribe M, Méndez-Sánchez N. The prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the Americas. Ann Hepatol. 2014;13:166–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Than NN, Newsome PN. A concise review of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Atherosclerosis. 2015;239:192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machado MV, Cortez-Pinto H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: what the clinician needs to know. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12956–12980. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.12956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corey KE, Kaplan LM. Obesity and liver disease: the epidemic of the twenty-first century. Clin Liver Dis. 2014;18:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson PA, Gardner SD, Lambie NM, Commans SA, Crowther DJ. Characterization of the human patatin-like phospholipase family. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1940–1949. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600185-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naik A, Košir R, Rozman D. Genomic aspects of NAFLD pathogenesis. Genomics. 2013;102:84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puppala J, Siddapuram SP, Akka J, Munshi A. Genetics of nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease: an overview. J Genet Genomics. 2013;40:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Browning JD. Common genetic variants and nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1191–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotronen A, Johansson LE, Johansson LM, Roos C, Westerbacka J, Hamsten A, Bergholm R, Arkkila P, Arola J, Kiviluoto T, et al. A common variant in PNPLA3, which encodes adiponutrin, is associated with liver fat content in humans. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1056–1060. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1285-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernaez R, McLean J, Lazo M, Brancati FL, Hirschhorn JN, Borecki IB, Harris TB, Nguyen T, Kamel IR, Bonekamp S, et al. Association between variants in or near PNPLA3, GCKR, and PPP1R3B with ultrasound-defined steatosis based on data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1183–1190.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takaki A, Kawai D, Yamamoto K. Molecular mechanisms and new treatment strategies for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:7352–7379. doi: 10.3390/ijms15057352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He S, McPhaul C, Li JZ, Garuti R, Kinch L, Grishin NV, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. A sequence variation (I148M) in PNPLA3 associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease disrupts triglyceride hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:6706–6715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xin YN, Zhao Y, Lin ZH, Jiang X, Xuan SY, Huang J. Molecular dynamics simulation of PNPLA3 I148M polymorphism reveals reduced substrate access to the catalytic cavity. Proteins. 2013;81:406–414. doi: 10.1002/prot.24199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smagris E, BasuRay S, Li J, Huang Y, Lai KM, Gromada J, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Pnpla3I148M knockin mice accumulate PNPLA3 on lipid droplets and develop hepatic steatosis. Hepatology. 2015;61:108–118. doi: 10.1002/hep.27242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pirazzi C, Adiels M, Burza MA, Mancina RM, Levin M, Ståhlman M, Taskinen MR, Orho-Melander M, Perman J, Pujia A, et al. Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (PNPLA3) I148M (rs738409) affects hepatic VLDL secretion in humans and in vitro. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1276–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valenti L, Rametta R, Ruscica M, Dongiovanni P, Steffani L, Motta BM, Canavesi E, Fracanzani AL, Mozzi E, Roviaro G, et al. The I148M PNPLA3 polymorphism influences serum adiponectin in patients with fatty liver and healthy controls. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bianchi G, Bugianesi E, Frystyk J, Tarnow L, Flyvbjerg A, Marchesini G. Adiponectin isoforms, insulin resistance and liver histology in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:439–451. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polyzos SA, Toulis KA, Goulis DG, Zavos C, Kountouras J. Serum total adiponectin in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism. 2011;60:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramezani-Moghadam M, Wang J, Ho V, Iseli TJ, Alzahrani B, Xu A, Van der Poorten D, Qiao L, George J, Hebbard L. Adiponectin reduces hepatic stellate cell migration by promoting tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) secretion. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:5533–5542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.598011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng XE, Wu YL, Lin SW, Lu QQ, Hu ZJ, Lin X. Genetic variants in PNPLA3 and risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a Han Chinese population. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Xing C, Tian Z, Ku HC. Genetic variant I148M in PNPLA3 is associated with the ultrasonography-determined steatosis degree in a Chinese population. BMC Med Genet. 2012;13:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-13-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitamoto T, Kitamoto A, Yoneda M, Hyogo H, Ochi H, Nakamura T, Teranishi H, Mizusawa S, Ueno T, Chayama K, et al. Genome-wide scan revealed that polymorphisms in the PNPLA3, SAMM50, and PARVB genes are associated with development and progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Japan. Hum Genet. 2013;132:783–792. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SS, Byoun YS, Jeong SH, Woo BH, Jang ES, Kim JW, Kim HY. Role of the PNPLA3 I148M polymorphism in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and fibrosis in Korea. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2967–2974. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3279-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhatt SP, Nigam P, Misra A, Guleria R, Pandey RM, Pasha MA. Genetic variation in the patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein-3 (PNPLA-3) gene in Asian Indians with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2013;11:329–335. doi: 10.1089/met.2012.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanth VVR, Sasikala M, Rao PN, Steffie Avanthi U, Rao KR, Nageshwar Reddy D. Pooled genetic analysis in ultrasound measured non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Indian subjects: A pilot study. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:435–442. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i6.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, Kang HM, Marth GT, McVean GA. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Grundy SM, Hobbs HH. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology. 2004;40:1387–1395. doi: 10.1002/hep.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Browning JD, Kumar KS, Saboorian MH, Thiele DL. Ethnic differences in the prevalence of cryptogenic cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:292–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmer ND, Musani SK, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Feitosa MF, Bielak LF, Hernaez R, Kahali B, Carr JJ, Harris TB, Jhun MA, et al. Characterization of European ancestry nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-associated variants in individuals of African and Hispanic descent. Hepatology. 2013;58:966–975. doi: 10.1002/hep.26440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qu HQ, Li Q, Grove ML, Lu Y, Pan JJ, Rentfro AR, Bickel PE, Fallon MB, Hanis CL, Boerwinkle E, et al. Population-based risk factors for elevated alanine aminotransferase in a South Texas Mexican-American population. Arch Med Res. 2012;43:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kallwitz ER, Daviglus ML, Allison MA, Emory KT, Zhao L, Kuniholm MH, Chen J, Gouskova N, Pirzada A, Talavera GA, et al. Prevalence of suspected nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Hispanic/Latino individuals differs by heritage. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox AJ, Wing MR, Carr JJ, Hightower RC, Smith SC, Xu J, Wagenknecht LE, Bowden DW, Freedman BI. Association of PNPLA3 SNP rs738409 with liver density in African Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 2011;37:452–455. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, Pennacchio LA, Boerwinkle E, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1461–1465. doi: 10.1038/ng.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petta S, Grimaudo S, Cammà C, Cabibi D, Di Marco V, Licata G, Pipitone RM, Craxì A. IL28B and PNPLA3 polymorphisms affect histological liver damage in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1356–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krawczyk M, Grünhage F, Zimmer V, Lammert F. Variant adiponutrin (PNPLA3) represents a common fibrosis risk gene: non-invasive elastography-based study in chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2011;55:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valenti L, Al-Serri A, Daly AK, Galmozzi E, Rametta R, Dongiovanni P, Nobili V, Mozzi E, Roviaro G, Vanni E, et al. Homozygosity for the patatin-like phospholipase-3/adiponutrin I148M polymorphism influences liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:1209–1217. doi: 10.1002/hep.23622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dongiovanni P, Donati B, Fares R, Lombardi R, Mancina RM, Romeo S, Valenti L. PNPLA3 I148M polymorphism and progressive liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6969–6978. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i41.6969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shen JH, Li YL, Li D, Wang NN, Jing L, Huang YH. The rs738409 (I148M) variant of the PNPLA3 gene and cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. J Lipid Res. 2015;56:167–175. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M048777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guyot E, Sutton A, Rufat P, Laguillier C, Mansouri A, Moreau R, Ganne-Carrié N, Beaugrand M, Charnaux N, Trinchet JC, et al. PNPLA3 rs738409, hepatocellular carcinoma occurrence and risk model prediction in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2013;58:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Falleti E, Fabris C, Cmet S, Cussigh A, Bitetto D, Fontanini E, Fornasiere E, Bignulin S, Fumolo E, Bignulin E, et al. PNPLA3 rs738409C/G polymorphism in cirrhosis: relationship with the aetiology of liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma occurrence. Liver Int. 2011;31:1137–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burza MA, Pirazzi C, Maglio C, Sjöholm K, Mancina RM, Svensson PA, Jacobson P, Adiels M, Baroni MG, Borén J, et al. PNPLA3 I148M (rs738409) genetic variant is associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in obese individuals. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:1037–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu YL, Patman GL, Leathart JBS, Piguet AC, Burt AD, Dufour JF, Day CP, Daly AK, Reeves HL, Anstee QM. Carriage of the PNPLA3 rs738409 C >G polymorphism confers an increased risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014;61:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chamorro AJ, Torres JL, Mirón-Canelo JA, González-Sarmiento R, Laso FJ, Marcos M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the I148M variant of patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 gene (PNPLA3) is significantly associated with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:571–581. doi: 10.1111/apt.12890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salameh H, Raff E, Erwin A, Seth D, Nischalke HD, Falleti E, Burza MA, Leathert J, Romeo S, Molinaro A, et al. PNPLA3 Gene Polymorphism Is Associated With Predisposition to and Severity of Alcoholic Liver Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:846–856. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singal AG, Manjunath H, Yopp AC, Beg MS, Marrero JA, Gopal P, Waljee AK. The effect of PNPLA3 on fibrosis progression and development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:325–334. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yasui K, Kawaguchi T, Shima T, Mitsuyoshi H, Seki K, Sendo R, Mizuno M, Itoh Y, Matsuda F, Okanoue T. Effect of PNPLA3 rs738409 variant (I148 M) on hepatic steatosis, necroinflammation, and fibrosis in Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:887–893. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-1018-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valenti L, Rumi M, Galmozzi E, Aghemo A, Del Menico B, De Nicola S, Dongiovanni P, Maggioni M, Fracanzani AL, Rametta R, et al. Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 I148M polymorphism, steatosis, and liver damage in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2011;53:791–799. doi: 10.1002/hep.24123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trépo E, Pradat P, Potthoff A, Momozawa Y, Quertinmont E, Gustot T, Lemmers A, Berthillon P, Amininejad L, Chevallier M, et al. Impact of patatin-like phospholipase-3 (rs738409 C& gt; G) polymorphism on fibrosis progression and steatosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2011;54:60–69. doi: 10.1002/hep.24350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petta S, Vanni E, Bugianesi E, Rosso C, Cabibi D, Cammà C, Di Marco V, Eslam M, Grimaudo S, Macaluso FS, et al. PNPLA3 rs738409 I748M is associated with steatohepatitis in 434 non-obese subjects with hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:939–948. doi: 10.1111/apt.13169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zampino R, Coppola N, Cirillo G, Boemio A, Grandone A, Stanzione M, Capoluongo N, Marrone A, Macera M, Sagnelli E, et al. Patatin-Like Phospholipase Domain-Containing 3 I148M Variant Is Associated with Liver Steatosis and Fat Distribution in Chronic Hepatitis B. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:3005–3010. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3716-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Viganò M, Valenti L, Lampertico P, Facchetti F, Motta BM, D’Ambrosio R, Romagnoli S, Dongiovanni P, Donati B, Fargion S, et al. Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 I148M affects liver steatosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2013;58:1245–1252. doi: 10.1002/hep.26445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valenti L, Maggioni P, Piperno A, Rametta R, Pelucchi S, Mariani R, Dongiovanni P, Fracanzani AL, Fargion S. Patatin-like phospholipase domain containing-3 gene I148M polymorphism, steatosis, and liver damage in hereditary hemochromatosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2813–2820. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i22.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stättermayer AF, Traussnigg S, Dienes HP, Aigner E, Stauber R, Lackner K, Hofer H, Stift J, Wrba F, Stadlmayr A, et al. Hepatic steatosis in Wilson disease--Role of copper and PNPLA3 mutations. J Hepatol. 2015;63:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krawczyk M, Portincasa P, Lammert F. PNPLA3-associated steatohepatitis: toward a gene-based classification of fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2013;33:369–379. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1358525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kozlitina J, Smagris E, Stender S, Nordestgaard BG, Zhou HH, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Vogt TF, Hobbs HH, Cohen JC. Exome-wide association study identifies a TM6SF2 variant that confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46:352–356. doi: 10.1038/ng.2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dezso Z, Nikolsky Y, Sviridov E, Shi W, Serebriyskaya T, Dosymbekov D, Bugrim A, Rakhmatulin E, Brennan RJ, Guryanov A, et al. A comprehensive functional analysis of tissue specificity of human gene expression. BMC Biol. 2008;6:49. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-6-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Available from: http://www.genecards.org.

- 64.Mahdessian H, Taxiarchis A, Popov S, Silveira A, Franco-Cereceda A, Hamsten A, Eriksson P, van’t Hooft F. TM6SF2 is a regulator of liver fat metabolism influencing triglyceride secretion and hepatic lipid droplet content. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:8913–8918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323785111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sookoian S, Castaño GO, Scian R, Mallardi P, Fernández Gianotti T, Burgueño AL, San Martino J, Pirola CJ. Genetic variation in transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 and the risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and histological disease severity. Hepatology. 2015;61:515–525. doi: 10.1002/hep.27556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dongiovanni P, Petta S, Maglio C, Fracanzani AL, Pipitone R, Mozzi E, Motta BM, Kaminska D, Rametta R, Grimaudo S, et al. Transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 gene variant disentangles nonalcoholic steatohepatitis from cardiovascular disease. Hepatology. 2015;61:506–514. doi: 10.1002/hep.27490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kahali B, Liu YL, Daly AK, Day CP, Anstee QM, Speliotes EK. TM6SF2: catch-22 in the fight against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease? Gastroenterology. 2015;148:679–684. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Holmen OL, Zhang H, Fan Y, Hovelson DH, Schmidt EM, Zhou W, Guo Y, Zhang J, Langhammer A, Løchen ML, et al. Systematic evaluation of coding variation identifies a candidate causal variant in TM6SF2 influencing total cholesterol and myocardial infarction risk. Nat Genet. 2014;46:345–351. doi: 10.1038/ng.2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu YL, Reeves HL, Burt AD, Tiniakos D, McPherson S, Leathart JB, Allison ME, Alexander GJ, Piguet AC, Anty R, et al. TM6SF2 rs58542926 influences hepatic fibrosis progression in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4309. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Claussnitzer M, Dankel SN, Kim KH, Quon G, Meuleman W, Haugen C, Glunk V, Sousa IS, Beaudry JL, Puviindran V, et al. FTO Obesity Variant Circuitry and Adipocyte Browning in Humans. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:895–907. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anderson RA, Rao N, Byrum RS, Rothschild CB, Bowden DW, Hayworth R, Pettenati M. In situ localization of the genetic locus encoding the lysosomal acid lipase/cholesteryl esterase (LIPA) deficient in Wolman disease to chromosome 10q23.2-q23.3. Genomics. 1993;15:245–247. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aslanidis C, Klima H, Lackner KJ, Schmitz G. Genomic organization of the human lysosomal acid lipase gene (LIPA) Genomics. 1994;20:329–331. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goldstein JL, Dana SE, Faust JR, Beaudet AL, Brown MS. Role of lysosomal acid lipase in the metabolism of plasma low density lipoprotein. Observations in cultured fibroblasts from a patient with cholesteryl ester storage disease. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:8487–8495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fasano T, Pisciotta L, Bocchi L, Guardamagna O, Assandro P, Rabacchi C, Zanoni P, Filocamo M, Bertolini S, Calandra S. Lysosomal lipase deficiency: molecular characterization of eleven patients with Wolman or cholesteryl ester storage disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;105:450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Assmann G, Seedorf U. Acid lipase deficiency: Wolman disease and cholesteryl ester storage disease. In: Scriver C, Beaudet A, Sly W, Valle D, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1995. p. 2563–2587. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Muntoni S, Wiebusch H, Jansen-Rust M, Rust S, Seedorf U, Schulte H, Berger K, Funke H, Assmann G. Prevalence of cholesteryl ester storage disease. United States: Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol; 2007. pp. 1866–1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Decarlis S, Agostoni C, Ferrante F, Scarlino S, Riva E, Giovannini M. Combined hyperlipidaemia as a presenting sign of cholesteryl ester storage disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009;32 Suppl 1:S11–S13. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-1027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hooper AJ, Tran HA, Formby MR, Burnett JR. A novel missense LIPA gene mutation, N98S, in a patient with cholesteryl ester storage disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2008;398:152–154. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Todoroki T, Matsumoto K, Watanabe K, Tashiro Y, Shimizu M, Okuyama T, Imai K. Accumulated lipids, aberrant fatty acid composition and defective cholesterol ester hydrolase activity in cholesterol ester storage disease. Ann Clin Biochem. 2000;37(Pt 2):187–193. doi: 10.1258/0004563001899195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bernstein DL, Hülkova H, Bialer MG, Desnick RJ. Cholesteryl ester storage disease: review of the findings in 135 reported patients with an underdiagnosed disease. J Hepatol. 2013;58:1230–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lohse P, Maas S, Lohse P, Elleder M, Kirk JM, Besley GT, Seidel D. Compound heterozygosity for a Wolman mutation is frequent among patients with cholesteryl ester storage disease. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hůlková H, Elleder M. Distinctive histopathological features that support a diagnosis of cholesterol ester storage disease in liver biopsy specimens. Histopathology. 2012;60:1107–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Romero-Gomez M, Eslam M, Ruiz A, Maraver M. Genes and hepatitis C: susceptibility, fibrosis progression and response to treatment. Liver Int. 2011;31:443–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Patel K, Norris S, Lebeck L, Feng A, Clare M, Pianko S, Portmann B, Blatt LM, Koziol J, Conrad A, et al. HLA class I allelic diversity and progression of fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2006;43:241–249. doi: 10.1002/hep.21040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eslam M, Hashem AM, Leung R, Romero-Gomez M, Berg T, Dore GJ, Chan HL, Irving WL, Sheridan D, Abate ML, et al. Interferon-λ rs12979860 genotype and liver fibrosis in viral and non-viral chronic liver disease. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6422. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bonkovsky HL, Lambrecht RW. Iron-induced liver injury. Clin Liver Dis. 2000;4:409–429, vi-vii. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(05)70116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bonkovsky HL, Hou W, Li T. Porphyrin and heme metabolism and the porphyrias. In: Wolkoff A, Lu S, Omary B, editors. Comprehensive Physiology. Bethesda, MD: Wiley and Co; 2013. pp. 365–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nelson JE, Klintworth H, Kowdley KV. Iron metabolism in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:8–16. doi: 10.1007/s11894-011-0234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Corradini E, Pietrangelo A. Iron and steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27 Suppl 2:42–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.07014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bonkovsky HL, Naishadham D, Lambrecht RW, Chung RT, Hoefs JC, Nash SR, Rogers TE, Banner BF, Sterling RK, Donovan JA, et al. Roles of iron and HFE mutations on severity and response to therapy during retreatment of advanced chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1440–1451. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Alla V, Bonkovsky HL. Iron in nonhemochromatotic liver disorders. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:461–472. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-923317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bonkovsky HL, Banner BF, Rothman AL. Iron and chronic viral hepatitis. Hepatology. 1997;25:759–768. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kowdley KV, Belt P, Wilson LA, Yeh MM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Chalasani N, Sanyal AJ, Nelson JE. Serum ferritin is an independent predictor of histologic severity and advanced fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2012;55:77–85. doi: 10.1002/hep.24706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Depalma RG, Hayes VW, Chow BK, Shamayeva G, May PE, Zacharski LR. Ferritin levels, inflammatory biomarkers, and mortality in peripheral arterial disease: a substudy of the Iron (Fe) and Atherosclerosis Study (FeAST) Trial. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:1498–1503. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.George DK, Goldwurm S, MacDonald GA, Cowley LL, Walker NI, Ward PJ, Jazwinska EC, Powell LW. Increased hepatic iron concentration in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is associated with increased fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:311–318. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70482-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bonkovsky HL, Jawaid Q, Tortorelli K, LeClair P, Cobb J, Lambrecht RW, Banner BF. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and iron: increased prevalence of mutations of the HFE gene in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:421–429. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Valenti L, Dongiovanni P, Fracanzani AL, Santorelli G, Fatta E, Bertelli C, Taioli E, Fiorelli G, Fargion S. Increased susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in heterozygotes for the mutation responsible for hereditary hemochromatosis. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:172–178. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Radio FC, Majore S, Aurizi C, Sorge F, Biolcati G, Bernabini S, Giotti I, Torricelli F, Giannarelli D, De Bernardo C, et al. Hereditary hemochromatosis type 1 phenotype modifiers in Italian patients. The controversial role of variants in HAMP, BMP2, FTL and SLC40A1 genes. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2015;55:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.McLaren CE, Emond MJ, Subramaniam VN, Phatak PD, Barton JC, Adams PC, Powell LW, Gurrin LC, Ramm GA, Anderson GJ, et al. Reply: To PMID 25605615. Hepatology. 2015;62:1918–1919. doi: 10.1002/hep.27851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.McLaren CE, Emond MJ, Subramaniam VN, Phatak PD, Barton JC, Adams PC, Goh JB, McDonald CJ, Powell LW, Gurrin LC, et al. Exome sequencing in HFE C282Y homozygous men with extreme phenotypes identifies a GNPAT variant associated with severe iron overload. Hepatology. 2015;62:429–439. doi: 10.1002/hep.27711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Facchini FS, Hua NW, Stoohs RA. Effect of iron depletion in carbohydrate-intolerant patients with clinical evidence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:931–939. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Valenti L, Fracanzani AL, Dongiovanni P, Bugianesi E, Marchesini G, Manzini P, Vanni E, Fargion S. Iron depletion by phlebotomy improves insulin resistance in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hyperferritinemia: evidence from a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1251–1258. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Valenti L, Fracanzani AL, Dongiovanni P, Rovida S, Rametta R, Fatta E, Pulixi EA, Maggioni M, Fargion S. A randomized trial of iron depletion in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hyperferritinemia. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3002–3010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i11.3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Adams LA, Crawford DH, Stuart K, House MJ, St Pierre TG, Webb M, Ching HL, Kava J, Bynevelt M, MacQuillan GC, et al. The impact of phlebotomy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology. 2015;61:1555–1564. doi: 10.1002/hep.27662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Raszeja-Wyszomirska J, Kurzawski G, Lawniczak M, Miezynska-Kurtycz J, Lubinski J. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and HFE gene mutations: a Polish study. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2531–2536. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i20.2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bugianesi E, Manzini P, D’Antico S, Vanni E, Longo F, Leone N, Massarenti P, Piga A, Marchesini G, Rizzetto M. Relative contribution of iron burden, HFE mutations, and insulin resistance to fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver. Hepatology. 2004;39:179–187. doi: 10.1002/hep.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Valenti L, Fracanzani AL, Bugianesi E, Dongiovanni P, Galmozzi E, Vanni E, Canavesi E, Lattuada E, Roviaro G, Marchesini G, et al. HFE genotype, parenchymal iron accumulation, and liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:905–912. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hernaez R, Yeung E, Clark JM, Kowdley KV, Brancati FL, Kao WH. Hemochromatosis gene and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1079–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ellervik C, Birgens H, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Hemochromatosis genotypes and risk of 31 disease endpoints: meta-analyses including 66,000 cases and 226,000 controls. Hepatology. 2007;46:1071–1080. doi: 10.1002/hep.21885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Salley TN, Mishra M, Tiwari S, Jadhav A, Ndisang JF. The heme oxygenase system rescues hepatic deterioration in the condition of obesity co-morbid with type-2 diabetes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hinds TD, Sodhi K, Meadows C, Fedorova L, Puri N, Kim DH, Peterson SJ, Shapiro J, Abraham NG, Kappas A. Increased HO-1 levels ameliorate fatty liver development through a reduction of heme and recruitment of FGF21. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:705–712. doi: 10.1002/oby.20559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 112.Chang PF, Lin YC, Liu K, Yeh SJ, Ni YH. Heme oxygenase-1 gene promoter polymorphism and the risk of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015;39:1236–1240. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zaman A. Abandon Phlebotomy in the Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. NEJM Journal Watch; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Grarup N, Urhammer SA, Ek J, Albrechtsen A, Glümer C, Borch-Johnsen K, Jørgensen T, Hansen T, Pedersen O. Studies of the relationship between the ENPP1 K121Q polymorphism and type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance and obesity in 7,333 Danish white subjects. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2097–2104. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0353-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.McGettrick AJ, Feener EP, Kahn CR. Human insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) polymorphism G972R causes IRS-1 to associate with the insulin receptor and inhibit receptor autophosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6441–6446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Dongiovanni P, Valenti L, Rametta R, Daly AK, Nobili V, Mozzi E, Leathart JB, Pietrobattista A, Burt AD, Maggioni M, et al. Genetic variants regulating insulin receptor signalling are associated with the severity of liver damage in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2010;59:267–273. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.190801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Speliotes EK, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Wu J, Hernaez R, Kim LJ, Palmer CD, Gudnason V, Eiriksdottir G, Garcia ME, Launer LJ, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies variants associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease that have distinct effects on metabolic traits. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Petta S, Miele L, Bugianesi E, Cammà C, Rosso C, Boccia S, Cabibi D, Di Marco V, Grimaudo S, Grieco A, et al. Glucokinase regulatory protein gene polymorphism affects liver fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87523. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tönjes A, Scholz M, Loeffler M, Stumvoll M. Association of Pro12Ala polymorphism in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma with Pre-diabetic phenotypes: meta-analysis of 57 studies on nondiabetic individuals. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2489–2497. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Vazquez-Chantada M, Gonzalez-Lahera A, Martinez-Arranz I, Garcia-Monzon C, Regueiro MM, Garcia-Rodriguez JL, Schlangen KA, Mendibil I, Rodriguez-Ezpeleta N, Lozano JJ, et al. Solute carrier family 2 member 1 is involved in the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2013;57:505–514. doi: 10.1002/hep.26052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Reue K, Zhang P. The lipin protein family: dual roles in lipid biosynthesis and gene expression. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Reue K. The lipin family: mutations and metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2009;20:165–170. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32832adee5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wiedmann S, Fischer M, Koehler M, Neureuther K, Riegger G, Doering A, Schunkert H, Hengstenberg C, Baessler A. Genetic variants within the LPIN1 gene, encoding lipin, are influencing phenotypes of the metabolic syndrome in humans. Diabetes. 2008;57:209–217. doi: 10.2337/db07-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Doege H, Grimm D, Falcon A, Tsang B, Storm TA, Xu H, Ortegon AM, Kazantzis M, Kay MA, Stahl A. Silencing of hepatic fatty acid transporter protein 5 in vivo reverses diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and improves hyperglycemia. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:22186–22192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803510200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Auinger A, Valenti L, Pfeuffer M, Helwig U, Herrmann J, Fracanzani AL, Dongiovanni P, Fargion S, Schrezenmeir J, Rubin D. A promoter polymorphism in the liver-specific fatty acid transport protein 5 is associated with features of the metabolic syndrome and steatosis. Horm Metab Res. 2010;42:854–859. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1267186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Utermann G, Hees M, Steinmetz A. Polymorphism of apolipoprotein E and occurrence of dysbetalipoproteinaemia in man. Nature. 1977;269:604–607. doi: 10.1038/269604a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Demirag MD, Onen HI, Karaoguz MY, Dogan I, Karakan T, Ekmekci A, Guz G. Apolipoprotein E gene polymorphism in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:3399–3403. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9740-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Sazci A, Akpinar G, Aygun C, Ergul E, Senturk O, Hulagu S. Association of apolipoprotein E polymorphisms in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:3218–3224. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lu H, Sun J, Sun L, Shu X, Xu Y, Xie D. Polymorphism of human leptin receptor gene is associated with type 2 diabetic patients complicated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:228–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zain SM, Mohamed Z, Mahadeva S, Cheah PL, Rampal S, Chin KF, Mahfudz AS, Basu RC, Tan HL, Mohamed R. Impact of leptin receptor gene variants on risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its interaction with adiponutrin gene. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:873–879. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zhou J, Zhai Y, Mu Y, Gong H, Uppal H, Toma D, Ren S, Evans RM, Xie W. A novel pregnane X receptor-mediated and sterol regulatory element-binding protein-independent lipogenic pathway. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15013–15020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511116200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sookoian S, Castaño GO, Burgueño AL, Gianotti TF, Rosselli MS, Pirola CJ. The nuclear receptor PXR gene variants are associated with liver injury in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2010;20:1–8. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328333a1dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kim H, Haluzik M, Asghar Z, Yau D, Joseph JW, Fernandez AM, Reitman ML, Yakar S, Stannard B, Heron-Milhavet L, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha agonist treatment in a transgenic model of type 2 diabetes reverses the lipotoxic state and improves glucose homeostasis. Diabetes. 2003;52:1770–1778. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Chen S, Li Y, Li S, Yu C. A Val227Ala substitution in the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha (PPAR alpha) gene associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and decreased waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1415–1418. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Yamakawa-Kobayashi K, Ishiguro H, Arinami T, Miyazaki R, Hamaguchi H. A Val227Ala polymorphism in the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) gene is associated with variations in serum lipid levels. J Med Genet. 2002;39:189–191. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.3.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Dongiovanni P, Rametta R, Fracanzani AL, Benedan L, Borroni V, Maggioni P, Maggioni M, Fargion S, Valenti L. Lack of association between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and gamma2 polymorphisms and progressive liver damage in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a case control study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:102. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Sookoian S, Castaño G, Gianotti TF, Gemma C, Pirola CJ. Polymorphisms of MRP2 (ABCC2) are associated with susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Nutr Biochem. 2009;20:765–770. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Buch S, Schafmayer C, Völzke H, Becker C, Franke A, von Eller-Eberstein H, Kluck C, Bässmann I, Brosch M, Lammert F, et al. A genome-wide association scan identifies the hepatic cholesterol transporter ABCG8 as a susceptibility factor for human gallstone disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39:995–999. doi: 10.1038/ng2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]