Abstract

The mechanisms that drive the spiral wrapping of the myelin sheath around axons are poorly understood. Two papers in this issue of Developmental Cell demonstrate that actin disassembly, rather than actin assembly, predominates during oligodendrocyte maturation and is critical for the genesis of the central myelin sheath.

The myelin sheath is essential for rapid conduction of action potentials along nerve fibers and is therefore critical for proper communication of neurons with each other and with their somatic targets. Myelin is also one of the most striking cellular specializations in all of biology. In the CNS, myelin is generated by oligodendrocytes, which contact and then ensheath and wrap around axons. The earliest electron micrographs of the process strongly suggested that myelin forms by circumnavigation of an inner glial membrane sequentially around an axon, which then compacts by excluding cytoplasm from between the membrane wraps (lamellae) (Bunge, 1968). Support for this notion was provided by a recent study demonstrating that myelin indeed grows by expansion of its inner turn and by extending along its lateral margins (Snaidero et al., 2014).

A major, unanswered question is what drives the rapid, circumferential spiraling of the inner glial membrane around an axon to generate the myelin sheath. The inner turn must extend into the space between the glia and the axon, disrupting existing interactions (Figure 1), strongly suggesting mechanical force is required. In this issue of Developmental Cell, Zuchero et al. and Nawaz et al. (2015) provide major new insights into this process. Using complementary approaches, they demonstrate that dynamic actin remodeling – in particular actin disassembly – is critical for myelin sheath formation.

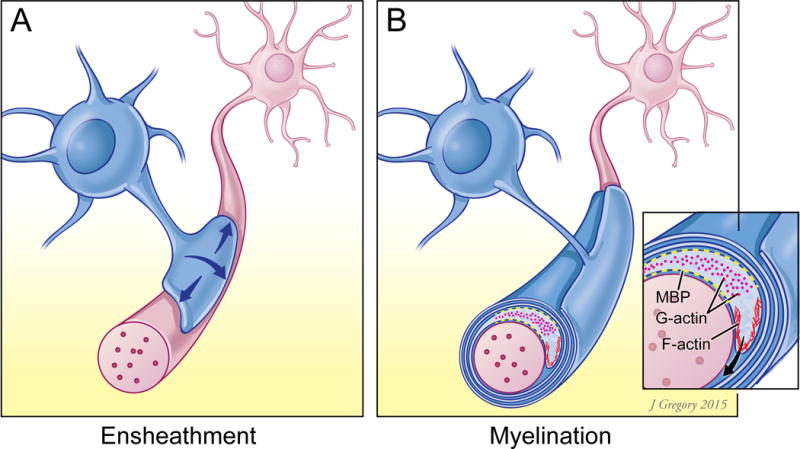

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of: A) an oligodendrocyte process at an early stage of axon ensheathment, when F-actin predominates and promotes ensheathment and B) a process actively myelinating an axon in which actin depolymerization, mediated by gelsolin and ADF/cofilin, predominates. The leading edge of the inner turn expresses F-actin subcortically whereas in regions enriched in MBP (shown in yellow) G-actin predominates, which is proposed to result from indirect activation of depolymerization.

The involvement of the actin cytoskeleton in myelination is consistent with the key role of actin in other morphogenetic events, notably cell motility (Blanchoin et al., 2014). In motile cells, branched and crosslinked actin networks provide the major engine for movement of the lamellipodium/leading edge by polymerizing against it and driving protrusion (Blanchoin et al., 2014). Actin is dynamically remodeled during this protrusion by both polymerizing/nucleating factors, such as members of the WASP (Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein) family, which regulate the Arp2/3 (Actin-Related Proteins) complex, and by depolymerizing factors (e.g., gelsolin and ADF/cofilin family members) which break down actin behind the front and free actin monomers (G-actin) for reassembly. Actin-independent modes of cell motility also occur, notably “bleb expansion” in which protrusion of the cell membrane is driven by hydrostatic pressure generated within the cytoplasm by contractile actomyosin forces (Paluch and Raz, 2013).

While glial cells are stationary during myelination, extension of their inner membrane around an axon can be likened to the leading edge of a migrating cell. Indeed, actin has previously been implicated in Schwann cell myelination (Fernandez-Valle et al., 1997) notably by conditional ablation of N-WASP, which results in profound defects (Jin et al., 2011; Novak et al., 2011). A previous report also found that WAVE, a member of the WASP family, contributes to oligodendrocyte myelination (Kim et al., 2006). However, the organization and dynamic regulation of actin during oligodendrocyte myelination has been poorly understood to this point.

Nawaz et al. and Zuchero et al. (2015) now systematically characterize and perturb the dynamic state of the actin cytoskeleton during oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination in cultures and in vivo. Both groups found F-actin levels were markedly reduced in white matter as myelination progressed. These findings were compellingly underscored at the cellular level in elegant live imaging studies in developing zebrafish. Using Lifeact-RFP as an F-actin reporter, Nawaz et al. show that F-actin is first broadly expressed by oligodendrocytes, then confined to a thin spiral presumptively corresponding to the leading edge of wrapping oligodendrocytes. When myelination is complete, F-actin was lost along the inner turn, although retained at the lateral edges. Thus, oligodendrocytes undergo a transition from actin-assembly during initial process elaboration and axon engagement to actin-disassembly during active myelination.

A similar transition occurs during oligodendrocyte maturation in vitro, which permits better resolution of dynamic F-actin changes due to oligodendrocytes’ flat membrane topology in culture. Both groups found that F-actin is initially abundant, but over time becomes concentrated at the rim of the cell (taken as the leading edge) and is lost or displaced from the flattened, intervening myelin basic protein (MBP)-positive membrane sheets (likely to correspond to membranes of the myelin lamellae), before being lost completely. As total actin levels do not change, these results again demonstrate a transition from F-actin to G-actin with maturation.

Zuchero et al. (2015) directly address the role of actin assembly during myelination by inhibiting the Arp2/3 complex. Components of the complex are enriched at the edge of cultured oligodendrocytes, in agreement with a similar localization of WAVE, an upstream regulator of Arp2/3 (Kim et al., 2006). Loss of Arp2/3 activity early in the oligodendroglial lineage impairs ensheathment and myelination of axons, supporting a role for F-actin during initial axon engagement. Unexpectedly, conditional ablation of Arp2/3 function during active myelination did not impede further myelination. In an imaginative variation, Zuchero et al. (2015) ablated Arp 2/3 function in the adult while simultaneously eliminating PTEN, which reactivates myelin wrapping in the adult (Snaidero et al., 2014). They found additional myelin wrapping occurred despite loss of Arp2/3. These results indicate that, unless Arp2/3 activity perdures after ablation or there are other as yet unknown compensating nucleating factors, actin assembly is surprisingly dispensable during myelination.

Both groups next addressed the role of actin disassembly during myelination. Consistent with a transition to G-actin, RNA-seq data indicates actin depolymerizing proteins are markedly upregulated in myelinating oligodendrocytes (Zhang et al., 2014). Zuchero et al. explore an additional mechanism that may contribute to actin depolymerization – competitive binding of MBP to PI(4,5)P2 on the inner leaflet of the membrane sheets – which is predicted to displace and thereby activate several depolymerizing proteins. Both groups observed that treating cultured oligodendrocytes with latrunculin A, depolymerizing actin, is accompanied by a striking increase in the flattened membrane regions. Zuchero et al. (2015) further show treatment with latrunculin A during in vivo development promoted myelination, increasing the resultant numbers of myelin lamellae. Both groups then characterized myelination in mice deficient in one or more actin depolymerizing proteins – an analysis complicated by the redundancy of depolymerizing components. In Nawaz et al. (2015), a conditional oligodendrocyte knockout of cofilin1 combined with a pan-ADF knockout resulted in persistence of F-actin, notably in the inner turn, and a concomitant decrease in overall myelination. Similarly, Zuchero et al. (2015) found a small but significant reduction in myelin thickness in the optic nerves of gelsolin-null mice. Taken together, these results strongly indicate that actin disassembly promotes myelin sheath formation.

A key question is how actin depolymerization drives myelin sheath formation. Nawaz et al. (2015) use laser trap and atomic force microscopy to show that loss of F-actin results in reduced membrane tension, facilitating membrane spreading and cell attachment, providing an additional mechanism for membrane expansion in the absence of actin. In contrast, the leading edge of oligodendrocytes, which is enriched in F-actin, has increased membrane tension and reduced adhesion, promoting its extension.

These studies together highlight a major and unexpected role of actin disassembly during myelination. A major question, and one on which the studies diverge, is what drives the protrusion of the leading edge. Is it F-actin-dependent as suggested by the live imaging in Nawaz et al., which appears to show F-actin at the leading edge during myelin formation or is it F-actin-independent as suggested by Zuchero et al., who show myelination proceeds in the absence of Arp2/3 function? In Nawaz et al., actin disassembly both facilitates membrane spreading and supports an iterative cycle of polymerization/depolymerization to generate an actin network at the leading edge that drives its protrusion. In contrast, Zuchero et al. suggest that forward propulsion of the leading edge is independent of actin polymerization and may be driven by increased hydrostatic pressure within the cell, which potentially builds up by zippering up of membrane sheets driven by MBP rather than via actomyosin contractility. Clarifying these distinct models, including whether both mechanisms of protrusion occur at different stages of myelination, promises additional critical insights into the genesis of this remarkable structure.

References

- Blanchoin L, Boujemaa-Paterski R, Sykes C, Plastino J. Physiological reviews. 2014;94:235–263. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge RP. Physiological reviews. 1968;48:197–251. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1968.48.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Valle C, Gorman D, Gomez AM, Bunge MB. The Journal of neuroscience. 1997;17:241–250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00241.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin F, Dong B, Georgiou J, Jiang Q, Zhang J, Bharioke A, Qiu F, Lommel S, Feltri ML, Wrabetz L, et al. Development. 2011;138:1329–1337. doi: 10.1242/dev.058677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, DiBernardo AB, Sloane JA, Rasband MN, Solomon D, Kosaras B, Kwak SP, Vartanian TK. The Journal of neuroscience. 2006;26:5849–5859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4921-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak N, Bar V, Sabanay H, Frechter S, Jaegle M, Snapper SB, Meijer D, Peles E. The Journal of cell biology. 2011;192:243–250. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paluch EK, Raz E. Current opinion in cell biology. 2013;25:582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaidero N, Mobius W, Czopka T, Hekking LH, Mathisen C, Verkleij D, Goebbels S, Edgar J, Merkler D, Lyons DA, et al. Cell. 2014;156:277–290. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chen K, Sloan SA, Bennett ML, Scholze AR, O’Keeffe S, Phatnani HP, Guarnieri P, Caneda C, Ruderisch N, et al. The Journal of neuroscience. 2014;34:11929–11947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]