Abstract

The conversion of cytosine to 5-methylcystosine (5mC) is an important regulator of gene expression. 5mC may be enzymatically converted to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), with a potentially distinct regulatory function. We sought to investigate these cytosine modifications and their effect on gene expression by parallel processing of genomic DNA using bisulfite and oxidative bisulfite conversion in conjunction with RNA sequencing. Although values of 5hmC across the placental genome were generally low, we identified ∼21,000 loci with consistently elevated levels of 5-hydroxymethycytosine. Absence of 5hmC was observed in CpG islands and, to a greater extent, in non-CpG island–associated regions. 5hmC was enriched within poised enhancers, and depleted within active enhancers, as defined by H3K27ac and H3K4me1 measurements. 5hmC and 5mC were significantly elevated in transcriptionally silent genes when compared with actively transcribed genes. 5hmC was positively associated with transcription in actively transcribed genes only. Our data suggest that dynamic cytosine regulation, associated with transcription, provides the most complete epigenomic landscape of the human placenta, and will be useful for future studies of the placental epigenome.—Green, B. B., Houseman, E. A., Johnson, K. C., Guerin, D. J., Armstrong, D. A., Christensen, B. C., Marsit, C. J. Hydroxymethylation is uniquely distributed within term placenta, and is associated with gene expression.

Keywords: 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, RNA-seq, DOHaD

DNA methylation is the covalent modification of cytosine to 5-methylcytosine (5mC), by DNA methyltransferase proteins. The presence of 5mC within a genomic promoter region is conventionally associated with a reduction in gene expression (1). The recent discovery of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), an oxidative product of 5mC, has broadened our understanding of epigenetic control of gene expression. Conversion of 5mC to 5hmC via oxidation is controlled by the ten-eleven translocation (TET) family of proteins as part of the genomic demethylation process (2). However, it is becoming increasingly evident that there is a potential for 5hmC to function, not only as a cellular intermediate in the DNA demethylation process, but also as a stand-alone stable epigenetic modification (3). Recent data suggest that 5hmC is distributed across numerous tissue types (4, 5), is overrepresented in enhancer regions, and is associated with increased gene expression (6, 7).

The extent and location of DNA methylation varies on a tissue-specific basis, with cellular identity heavily influenced by these epigenetic patterns (8, 9). Similarly, early data suggest that hydroxymethylation levels also exhibit tissue-specific patterns (5). For example, brain tissue, for which 5hmC patterns have been well defined, contains hydroxymethylation at a 5–10 times greater extent than has been described in other cell types (10–12), including osteoarthritic chondrocytes (13) and embryonic stem cells (14), when measured at a single-base-pair resolution, and in peripheral blood when measured with a sequencing-based tool (15). In addition, studies describing the relationship between 5hmC and gene expression on a genome-wide scale have been scarce, although hydroxymethylation has been correlated recently with expression and differentiation in colonocytes (16). The extent and distribution of 5hmC within the human placenta have yet to be described.

The placenta is an important mediator in the communication between the developing fetus and the maternal environment. Studies of the placenta’s role in the developmental origins of health and disease are becoming increasingly common. The placenta regulates maternal–fetal nutrient and waste exchange, facilitates interactions with the maternal immune system, and acts as a neuroendocrine organ by producing hormones and growth factors critical to the developing fetus. Gene expression within the placenta is recognized to be regulated, in part, by epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation (17), and there is a growing body of literature on the impact of various environmental factors on placental DNA methylation and of placental methylation on child health outcomes (18, 19). Among these, targeted analysis of placental hydroxymethylation within the H19 imprinted gene region highlighted a potential link to infant birth weight (20). However, there is still a gap in our understanding of both the distribution and function of placental 5hmC at an epigenome-wide level. To this end, we have described the 5hmC landscape in 23 healthy placentas at a single-base-pair resolution. We observed enrichment for elevated levels of 5hmC in functionally relevant regions, including repetitive elements, DNase I-hypersensitive sites, previously identified sites of poised and active enhancers, and in relation to gene bodies and CpG islands. To further investigate the functional relevance of 5hmC and 5mC, we compared these values to gene expression levels obtained via RNA sequencing in a subset of 20 matched samples. In addition, we leveraged publicly available gene expression data from healthy placentas at various developmental stages to determine whether hydroxymethylation is enriched in transitionally expressed genes. We also used a novel algorithm to discern 5hmC from 5mC array values. Such a distinction is important, to aid in the interpretation of DNA methylation data generated by placental tissue, to assure that the appropriate epigenetic feature (5mC vs. 5hmC) is being evaluated, and to understand whether this specific modification may also play a necessary functional role in placental physiology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection

The 23 individuals selected for hydroxymethylation profiling were representative of the overall characteristics of the Rhode Island Child Health Study (RICHS), which enrolled a total of 899 mother/infant pairs at Woman and Infant’s Hospital of Rhode Island (Providence, RI, USA), from September 1, 2009, through July 31, 2014 (Table 1). All subjects provided written informed consent and the study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Women and Infants Hospital and Dartmouth College. For each subject and within 2 h of delivery, samples of placenta parenchyma (totaling ∼8–10 g tissue) were excised. All samples were taken from the fetal side of the placenta, 2 cm from the umbilical cord insertion site, free of maternal decidua. The samples were placed immediately in RNAlater (Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and stored at 4°C. At least 72 h later, DNA was extracted by using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), quantified with the Qubit Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences), and stored at −80°C.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive maternal and infant characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Maternal age (yr) | 29.8 ± 5.2 |

| Maternal BMI | 27.5 ± 7.3 |

| Gestational age (wk) | 38.8 ± 1.0 |

| Male | 12 (52%) |

| Female | 11 (48%) |

| SGA | 8 (35%) |

| AGA | 8 (35%) |

| LGA | 7 (30%) |

| Maternal smoking | |

| Yes | 2 (9%) |

| No | 17 (74%) |

| No response | 4 (17%) |

AGA, appropriate for gestational age; BMI, body mass index; LGA, large for gestational age; SGA, small for gestational age. Data are means ± sd or number of infants (percentage of total study sample).

DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation profiling

Bisulfite (BS) and oxidative bisulfite (oxBS) conversion were conducted using the TrueMethylSeq conversion kit (Cambridge Epigenetix, Cambridge, United Kingdom) with a modified protocol to optimize for downstream analysis using the 450 HumanMethylationBead Chip Array (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), according to the previously described low-input (∼500 ng) protocol (21).

Normalization and background correction of raw signals from each of the BS- and oxBS-converted samples was using the FunNorm procedure available in the R/Bioconductor package minfi (version 1.10.2; https://www.bioconductor.org). We applied a novel technique for estimating the 5mC, 5hmC, and unmethylated proportions. In brief, each CpG corresponded to a data vector (SBS, RBS, SOxBS, and ROxBS), with Rk representing total signal (Cy3+Cy5) and Sk representing Cy5 signal [k ∈ (BS, oxBS)]; we used maximum likelihood to fit the data-generating model: SBS ~β[RBS(π2 + π3), RBSπ1], SOxBS ~β[ROxBSπ2, ROxBS(π1 + π3)] under the constraints πj > 0 (j ∈ {1,2,3}), π1 + π2 + π3 = 1, thus estimating parameters π1 (unmethylated proportion), π2 (5mC proportion), and π3 (5hmC proportion). Note that this method explicitly disallows negative proportions, although we observed numerical zero values of 5hmC (π3 < 10−16). This method is publically available within the Comprehensive R Archive Network repository within the OxyBS package (https://cran.r-project.org). Afterward, we removed probes with a detection P > 0.01 for at least 1 sample, CpG loci on sex chromosomes, as well as those previously identified as cross-reactive (22) or containing SNPs, resulting in 312,258 CpG loci remaining from the original 486,000 for our analysis. The R code for the maximum-likelihood estimation of 5mC and 5hmC, as applied to 450 K arrays, is available online (http://www.christensen-lab.com).

Hydroxymethylation is of concern in methylation profiling, in that it may be misidentified after BS conversion as 5mC rather than 5hmC. We determined the percentage of misidentification for each locus due to BS conversion as: %ERR = [μH/(μH + μM)] ⋅ 100, with μH equal to the average hydroxymethylation value for that loci and μM equal to the average methylation value for the same loci.

We also worked to identify loci where the extent of 5hmC was consistently elevated across our samples, highlighting areas where hydroxymethylation may be functionally relevant. We defined these locations within the placenta as loci with a 5hmC proportion greater than 0.10 in at least 12 of the 23 samples (>50%) and considered these to be sites of systematic hydroxymethylation within healthy placenta. The raw data, as well as the normalized 5mC and 5hmC values, are available through the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE71719 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE71719).

RNA sequencing

RNA was collected from placenta using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), and samples with an RNA integrity number above 5.0 were kept for sequencing (n = 19). These 19 samples were all from the 23 interrogated for 5mC and 5hmC. Paired end libraries were prepared and sequenced on a HiSeq2000/2500 (Illumina) at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine Center for Genome Technology (Miami, FL, USA), according to their standard protocol. Across samples, an average of 42.3 million paired reads, with an average quality of 34.5 were obtained. Sequences from each sample were aligned to the human genome build 19 (hg19) using TopHat2 default parameters (23), with an average of 27.1 million reads (∼64% mapping rate) mapping successfully. After alignment, gene counts were estimated using Cufflinks (24), which employs a fragment bias correction (25) and estimates expression levels normalized to sample library size and gene size, presented as fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM). Genes with a median FPKM < 0.5 and a standard deviation below 0.1 were considered to be nonexpressed and were separated from the remaining genes. FPKM values were then log transformed to obtain a normal distribution with log2(FPKM+1). The constant value added to the FPKM acts as a pseudo count to avoid infinite values from those with an FPKM = 0. For the purposes of investigating the extent of both 5hmC and 5mC in the genomic-specific context and in relation to distance to transcription start site (TSS), genes were binned into 4 categories based on expression level: no expression and tertiles of low, middle, and high among those expressed. We then mapped the average 5mC/5hmC values for genes within each expression group against the distance to the TSS. We used the TSS provided for each gene from the University of California at Santa Cruz (UCSC) genome browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu). Raw sequences are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) Sequence Read Archive (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) under accession number SRP068290.

Genomic classification

To determine whether 5hmC enrichment occurs at functionally relevant sites within the genome, we classified probes based on available information from the 450K array annotation file provided by Illumina. This process included classification of the relationship to a CpG island, location relative to associated genes, and determination of whether a probe is within a DNase–hypersensitive site. In addition, we identified probes within LINE1-repetitive elements based on the UCSC genome browser.

Using publically available ChIP-Seq data from the NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Project (http://www.roadmapepigenomics.org), we identified loci as enriched within the placenta for H3K4me1 (GEO accession: GSM1102795), as well as H3K27ac (GEO accession: GSM1102784). We considered the presence of H3K4me1 alone to act as a marker of poised enhancers, whereas regions with both H3K27ac and H3K4me1 or with H3K27ac alone represent active enhancer sites. We created a map of enrichment for these markers using the R package GenomicRanges (Bioconductor), in which our threshold of enrichment was P < 0.01 above background signal, as recommended by the Roadmap Project. This threshold identified 134,054 and 120,970 loci of enriched H3K4me1 and H3K27ac, respectively, within our data set of 312,258 probes.

Because hydroxymethylation is found near, but often not within, transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) (26) we determined whether a CpG was located within 500 bp in either direction of the 176 computationally predicted TFBS sequences obtained from the tfbsConsSites track of the UCSC Genome Browser (z score > 2). We compared the proportion of systematic hydroxymethylation within these proximal TFBS locations in contrast to loci outside of these by Fisher’s exact test. To account for multiple comparisons, we applied a Bonferroni correction to the P-value for each of the transcription factors.

Analysis of publically available expression data

We sought to determine the effect of hydroxymethylation on transitional gene expression within the placenta using publicly available data [GEO: GDS4037; processing described within (27)]. Data generated for this study examined expression of placental genes at 3 separate time points of gestation, within the first trimester, second trimester, and in term placentas using the Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences). We focused our analysis on second trimester and term placentas. We identified 655 genes that demonstrated differential expression at the second trimester compared to term placenta by linear regression. Genes were considered to have transient expression between the second trimester and term at P < 1.85 × 10−6, which is equivalent to a Bonferroni-corrected value of P = 0.05. We considered these genes to be ones with transitional expression leading up to term, and specifically focused on genes with increased expression over this period because of previous associations between 5hmC and high expression. Using a Mantel-Haenszel test, we determined whether systematic hydroxymethylation is enriched at genes with increased transitional expression leading up to term.

Statistical analysis

Each locus was assigned a binomial classifier for systematic hydroxymethylation, as well as for an aspect of genomic classification, including DNase I hypersensitivity, residence within a repetitive element, location within a gene (4 separate vectors for each category: TSS, 5′UTR, body, 3′UTR), and relationship to CpG island (4 separate vectors for each category: island, shore, shelf, and open sea). We then used a 2 × 2 × k contingency table within a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test to compare proportions of loci demonstrating systematic hydroxymethylation within a genomic classifier against those not demonstrating systematic 5hmC, stratified by probe type:relationship to CpG island (i.e., Type I:Island, Type II:Island, Type I:Shore, and so on, totaling 8 strata). This strategy was used to determine whether hydroxymethylation was enriched, depleted, or the same as nonsystematic probes for each genomic classifier. We stratified by probe type because of the known bias in methylation values associated with this characteristic (28) and also by relationship to CpG island caused by the extreme differences seen in hydroxymethylation values because of this classification. For the test determining enrichment by CpG island status, we stratified the data only by probe type. Enrichment of 5hmC at poised and active enhancer regions was determined by Fisher’s exact test. Correlation of the extent of 5hmC and 5mC within loci was conducted by Pearson’s correlation test.

RESULTS

Genomic hydroxymethylation

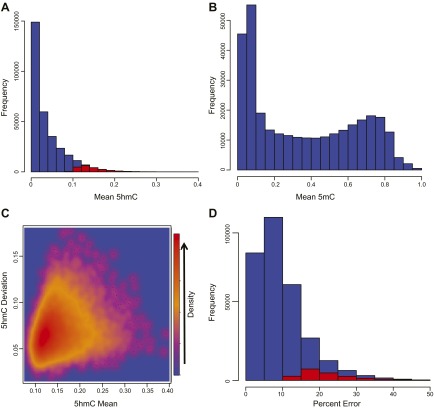

The extent of 5hmC present within the placental epigenome was notably lower than the more widely studied 5mC mark. Mean hydroxymethylation values for the 312,258 loci averaged across all samples ranged from 0–39%, although 5hmC proportions displayed a strong right skew, with the 23 samples having a grand mean of 3.69% and a median of medians of 1.01% hydroxymethylation (Fig. 1A). To determine CpG loci with consistently elevated hydroxymethylation across samples, we defined systematic regions of 5hmC as loci with a proportion greater than 0.10 in at least 12 of the 23 samples. We identified 21,302 loci within these parameters (Supplemental Table 1), which had a median 5hmC value of 13.73%, with a median deviation of 6.68% (Fig. 1A). In contrast, 5mC within these samples demonstrated a bimodal distribution, having a mean of loci across samples of 35.6% and a median of medians of 29.7% methylation (Fig. 1B). Although most of the CpGs demonstrate low levels of 5hmC with little variation, there is a nonnegligible proportion of sites with various 5hmC levels demonstrating considerable interplacental variability. The standard deviation of the ∼21,000 systematic probes ranged from 1.9–17.6% (Fig. 1C), and on average the deviation was equal to ∼49% of the 5hmC value. Because methylation arrays that use only BS conversion cannot distinguish between 5hmC and 5mC, we next calculated the estimated disparity in 5mC levels if these samples had been run using only BS conversion as the mean 5hmC value for a given loci divided by the sum of mean 5hmC and 5mC. The percentage error ranged from 0 to 73%, but it is important to note that there was a strong right skew and the mean and median percentage error was 9.7 and 8.1%, respectively (Fig. 1D). Of the 21,302 loci with systematic hydroxymethylation, 21,300 and 10,855 loci had error rates greater than 10 and 20%, respectively, with an overall shift to the right in the error associated with these probes.

Figure 1.

Extent of 5hmC and 5mC within the placenta. A) The distribution of hydroxymethylation across the placental epigenome (blue) with probes identified as systematic sites (red). B) The bimodal distribution of 5mC across the placental epigenome. C) The relationship of mean 5hmC for all 23 individuals at each locus, in contrast with the deviation across samples. The color scale is presented in arbitrary units that are used to demonstrate the relative density. D) The estimated error in 5mC for each probe that would be found on arrays using only BS conversion, based on the proportion of signal determined to be 5hmC after oxBS conversion. Probes determined to demonstrate systematic hydroxymethylation are highlighted in red.

Hydroxymethylation and 5mC

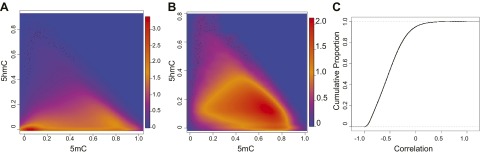

To evaluate the etiology and relevance of 5hmC, we examined the relationship between levels of 5hmC and 5mC within loci to determine whether hydroxymethylation was present as a byproduct of abundant levels of 5mC. Most of the probes fell within a low range for both hydroxymethylation and methylcytosine, although probes with high methylcytosine had limited 5hmC values (Fig. 2A). When we limited the probes to just those with systematic hydroxymethylation, most had a 5mC value within the 0.6–0.8 range (Fig. 2B), but a large proportion of probes demonstrated a negative correlation for 5hmC in relation to 5-methylcytosine (Fig. 2C). Overall, >90% of the probes demonstrated a negative correlation.

Figure 2.

Relationship between 5hmC and 5mC within loci. A) Distribution of 5mC and 5hmC across all probes on the array. B) Distribution of 5mC and 5hmC for probes demonstrating systematic hydroxymethylation. C) The cumulative proportion of r values from Pearson correlations testing the relationship between 5mC and 5hmC. The color scale is presented in arbitrary units that are used to demonstrate the relative density.

Localization of hydroxymethylation

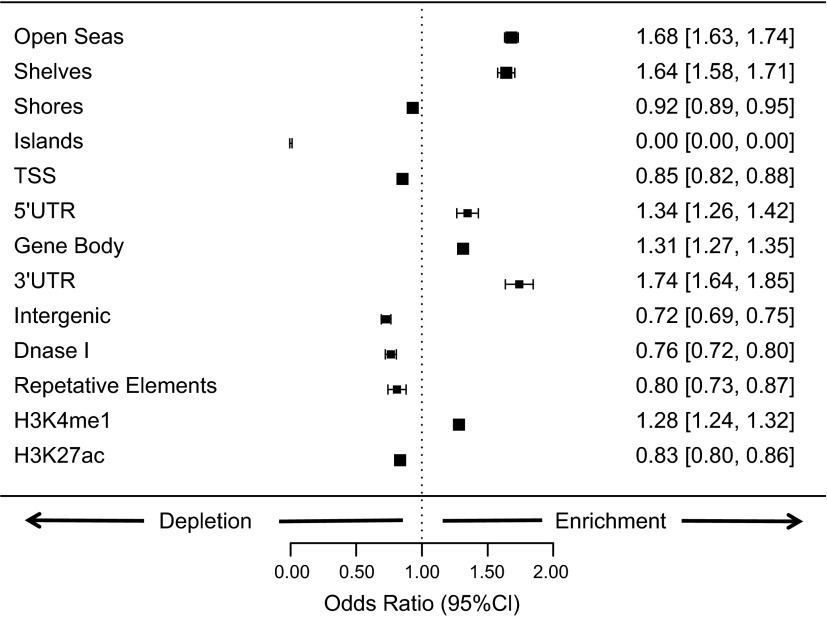

We observed an enrichment of systematic hydroxymethylation (Fig. 3) at CpG open sea (OR = 1.68; 95% CI 1.62–1.73) and shelf regions (OR = 1.64; 95% CI 1.58–1.71), whereas CpG shores were depleted of hydroxymethylation (OR = 0.92; 95% CI 0.89–0.95). We also observed a striking lack of systematic hydroxymethylation sites within CpG islands (OR = 0.0; 95% CI 0.0–0.0001). This low OR is most likely related to the occurrence of only 5% of systematic hydroxymethylation within CpG island-associated probes (1094 of 21,302 probes), whereas more than 34% of the total probes on our array are normally associated with CpG islands (107,139 of 312,258 probes). As a result, we stratified all other comparisons by both probe type and relationship to CpG island. When investigating 5hmC in relation to genes, we saw a significant enrichment of hydroxymethylation conservation in the gene body (OR = 1.31; 95% CI 1.27–1.35), as well as the 5′ UTR (OR = 1.34; 95% CI 1.26–1.42) and 3′ UTR (OR = 1.74; 95% CI 1.63–1.84). In contrast, there was a significant depletion in hydroxymethylation at TSS (OR = 0.85; 95% CI 0.82–0.88) and intergenic gene regions (OR = 0.72; 95% CI 0.69–0.75). Finally, we examined loci within DNase I hypersensitive sites and those within LINE-1 repetitive elements. We found a depletion in hydroxymethylation for both hypersensitive sites (OR = 0.76; 95% CI 0.72–0.80) and loci within repetitive elements (OR = 0.80; 95% CI 0.73–0.87).

Figure 3.

Distribution of systemic 5hmC across the genome by regional classification. ORs and 95% Cis are shown for inclusion of systematic hydroxymethylation within groups of genomic classes. ORs were determined by Mantel-Haenszel test, stratified for probe type and relation to CpG island, except for tests of enrichment for CpG islands, shores, shelves, and open seas, which were stratified only by probe type. ORs above 1.0 indicate enrichment for systematic hydroxymethylation in comparison to other location classifiers, and ORs below 1.0 indicate depletion.

Relationship between hydroxymethylation and histone modifications

The presence of H3K4me1, as identified by ChIP-Seq in the Epigenome Roadmap data, indicates the location of poised enhancers. We observed significant enrichment of systematic hydroxymethylation at CpG loci within these regions (OR = 1.28; 95% CI 1.24–1.32). In contrast, hydroxymethylation was depleted in regions with high levels of H3K27ac (OR = 0.83; 95% CI 0.80–0.86), a marker of active enhancers. After adjustment for multiple hypothesis testing, systematic hydroxymethylation demonstrated significant enrichment at only 1 TFBS: homeobox protein NKX3.1 (NKX3-1) (OR = 1.44; 95% CI 1.18–1.75).

RNA sequencing

Total RNA from 19 unique samples, matched to individuals with available 5mC and 5hmC array data, was sequenced for whole transcriptome assessment; 12,336 genes were found to demonstrate appreciable expression levels within the term placenta. Genes that did not meet our criteria were considered transcriptionally silent. To investigate the association between cytosine modifications and placental gene expression, we restricted our analysis to those 21,000 CpGs with elevated hydroxymethylation (i.e., systematic 5hmC CpGs). A directed analysis of those 21,000 CpGs exhibiting appreciable 5hmC levels allowed us to avoid spurious associations due to CpGs with 5hmC estimates too low to contain meaningful variability. Next, we removed any CpGs that were not located within or proximal to hg19-described genes, resulting in a total of 13,511 CpG-gene pairs that we tested for associations between 5hmC/5mC and gene expression. Rho values for correlations between 5hmC and normalized expression levels ranged from −0.80 to +0.69 (Fig. 4), with 734 loci demonstrating a nominally significant association between 5hmC and expression (P < 0.05); however, after Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons, no CpGs demonstrated a significant association with gene expression.

Figure 4.

Distribution of 5hmC, 5mC, and expression levels across the genome. Circos plot acting as a circular representation of the human genome. The outermost ring (blue scale) is a heatmap representing expression within that region. The middle ring (purple scale) exhibits the level of 5hmC associated with the ∼21,000 sites of systemic hydroxymethylation. The innermost ring (red scale) represents the relative level of 5mC within those same 21,000 sites. For each ring, darker colors indicate higher values. Each ring is on an independent scale, and the heatmap should be used only to compare relative values within a measurement and should not be taken as a representation of the relationship among expression, 5hmC, and 5mC.

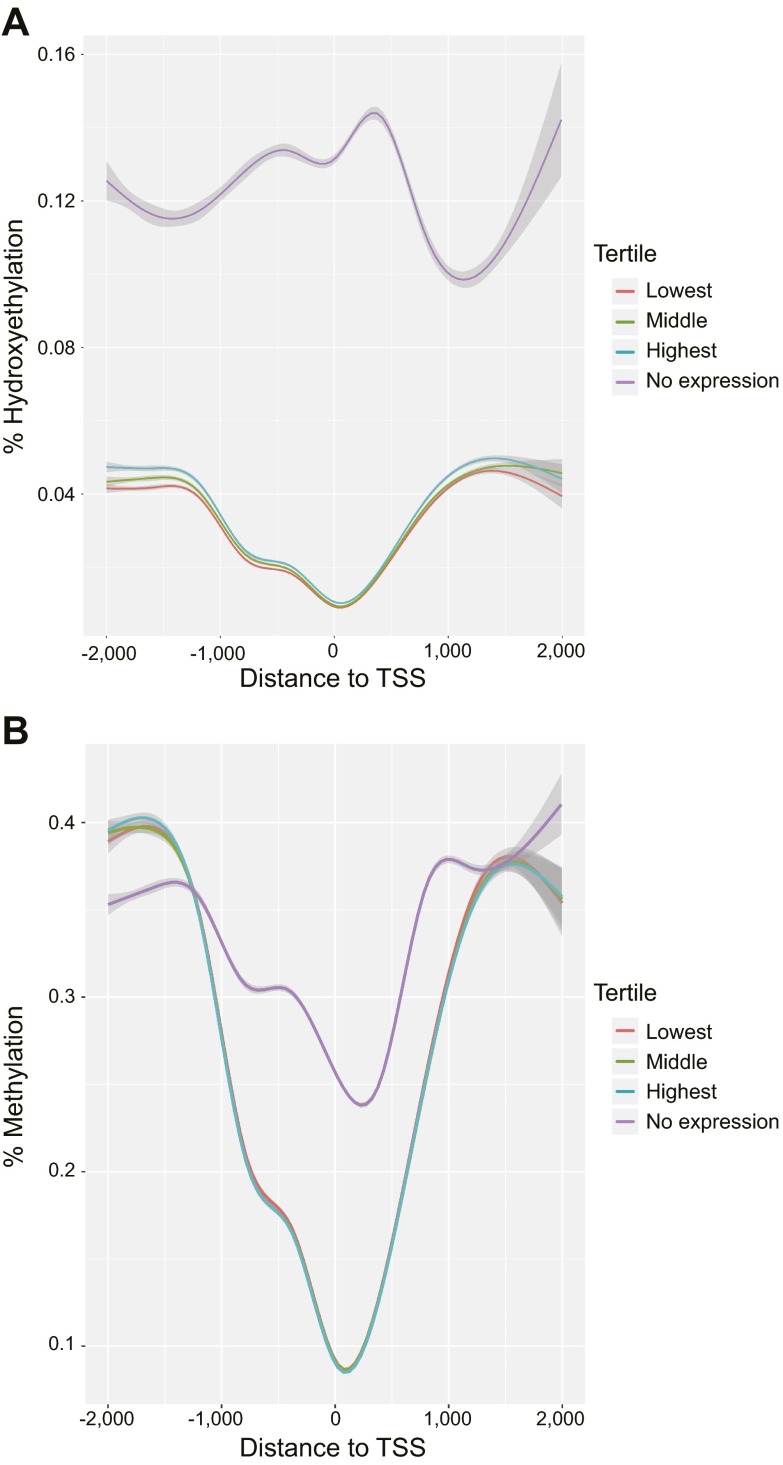

To determine whether there is a genomic-context–specific relationship among 5mC, 5hmC, and transcription levels, we mapped the levels for each cytosine modification to their distance to the TSS. For both 5hmC (Fig. 5A) and 5mC (Fig. 5B), estimates were highest ∼1000 bp in either direction of the TSS, with the lowest values reported at the approximate site of transcription initiation. This pattern, however, did not hold true for measurements of 5hmC within transcriptionally silent genes. In contrast, 5hmC values for these genes were slightly elevated at the TSS, whereas the level of 5hmC decreased slightly at −1500 and +1000 bp, relative to the TSS. Expressed genes did not demonstrate any difference for 5mC values between −2000 bp upstream and +2000 bp downstream of the TSS; however, there was a relative increase in 5hmC values shown by the increased expression for loci located between approximately −1800 and +1500 bp in relation to the TSS. There was also a marked increase in both 5mC and 5hmC values within genes that were not expressed from our data set.

Figure 5.

Extent of 5hmC and 5mC at the TSS and corresponding gene expression. Plot of the relationship between level of 5hmC (A) and 5mC (B) plotted against distance to the TSS for samples within the 3 tertiles of expression for each gene, as well as for genes with no expression. Gray shading surrounding each line represents the 95% CI for the true value at that location.

Hydroxymethylation and transitional gene expression

The placental expression profiles are known to vary at different stages of development. We hypothesized that 5hmC marks those genes that demonstrate transitional gene expression, given that 5hmC is recognized to serve as an intermediate in DNA demethylation. Using gene expression data from healthy placentas at trimester 2 and at term (GEO: GDS4037), we examined whether genes harboring systematic 5hmC demonstrate various levels of expression across pregnancy. We defined genes with transitional expression across gestational ages as those that demonstrated significantly different expression (n = 655) in the term placenta compared with second-trimester samples (Supplemental Table 2). Transitional genes with increased expression between the second trimester and term were significantly (P < 0.001) more likely to harbor CpG sites with systematic hydroxymethylation (OR = 2.70; 95% CI 2.48–2.93) than genes that either did not demonstrate altered expression at term or showed a decrease in expression.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have described the genomic landscape of hydroxymethylation within a subset of healthy infant placental tissue samples, by using paired BS- and oxBS-converted DNA on the Illumina 450K methylation bead chip. A better understanding of the distribution of placental 5hmC is crucial to refining our understanding of data that, to date, have not distinguished between these modifications (29). In addition, we determined the extent to which 5hmC and 5mC are associated with gene expression. Together, we believe these findings will affect the perception of cytosine modifications in placental studies and may offer an early insight into the role of 5hmC in gene regulation in this tissue.

Earlier investigators used similar BS and oxBS conversion on 450K arrays and demonstrated the ability of this technology to differentiate between 5hmC, 5mC, and unmodified cytosine residues (21, 30). However, these studies used a subtraction method to determine levels of hydroxymethylation, and because of technical variation and error in individual array measures, resulting 5hmC or 5mC values could fall below 0, and the sum of the 5hmC, 5mC, and cytosine estimations exceeded, in many instances, 1. To avoid these overshoot values and provide a more robust approximation of 5hmC, we used a probabilistic maximum likelihood estimation in which the sum of the 3 parameters could not be above 1, and no individual measurement could be below 0. This method was used to reduce the noise present within the comparison of multiple arrays, each with their own inherent technical error.

There were ∼21,000 loci within our array that met the criteria that we established for probes demonstrating systematic hydroxymethylation within the placenta. Hydroxymethylation has been described as both an intermediate in the demethylation process (2) and a stable epigenetic modifier (4). In this regard, we hoped to establish these criteria to distinguish between 5hmC that fall within each of these categories. The hydroxymethylation present within our biopsies because of random sampling of cells undergoing active demethylation would most likely be observed in a limited number of samples, whereas regions of stable 5hmC with functional significance would be measured in a greater number or, as we defined it, most of the samples. We recognize that this may be viewed as an arbitrary cutoff point, based on our limited sample size; however, we determined that measurable 5hmC (i.e., >0.1) in more than half our cohort would offer an early list of candidate loci for future validation in additional cohorts.

As these regions are relatively systematic across samples, they represent CpGs that are most likely to be misclassified as 5mC in studies focused only on 5mC modification by using traditional BS treatment methodologies. To investigate whether the regions we identified with demonstrable 5hmC levels may be misrepresented as 5mC in the existing literature, we examined a selection of journal articles curated to include all aspects of DNA methylation within the placenta, and for ease of comparison, we used the Infinium 450K array indexed within the NCBI PubMed database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) that matched the search terms “placenta” and “DNA methylation” from the last 2 yr and found 5 publications (31–35) that had identified 123 loci with variable methylation associated with some aspect of exposure or birth outcome. Of the 123 probes identified, only 2 were also contained within the ∼21,000 loci demonstrating systematic hydroxymethylation identified in our study. The sites map to exostosin (EXT)-1 [cg01423426, (31)] and transcription regulator protein BACH2 [cg18477569, (35)], each associated with gestational diabetes within their respective studies. Although we only surveyed a small number of studies investigating placental epigenetics, focusing on a single technology, the low number of probes identified with any measurable 5hmC suggests that the issue may be limited in scope for healthy tissues. In addition, identification of these probes on our list does not exclude the results from validation, but in the future may suggest that sites listed herein require additional scrutiny because of the high level of hydroxymethylation present across most samples. Although one cannot expect all future studies to use paired BS and oxBS to consider the true levels of 5mC and 5hmC because of the prohibitive cost, we suggest that future studies investigating hydroxymethylation within the placenta should cross-reference significant results against these 21,000 probes to ensure that any loci of interest is not confounded by the increased error introduced by the elevated 5hmC levels within them as described in this study.

The nonnegligible variation in these systematic sites of 5hmC across the 23 samples, relative to the 5hmC value (deviation equal to 49% of the mean 5hmC), suggests that there is interindividual variability at these sites as well, which indicates that there may be utility in more focused studies of these systematic regions demonstrating interindividual variability, because such studies may portend areas of functional significance, those with the potential to be modified by environmental factors, or those that may affect outcomes.

We investigated the enrichment or depletion of systematic hydroxymethylation at functionally relevant genomic regions in addition to the association between identified loci and gene expression from publically available data. Although no comparable study has been conducted in the placenta, our results align closely with previous data from the human brain, the organ currently with the most comprehensive 5hmC analysis. These similarities include the striking lack of hydroxymethylation in CpG islands, an element often associated with gene promoters that is depleted in both 5hmC and 5mC in the brain (11, 36). Although our data agree with previous findings in the brain, both of these tissues appear to be in contrast with embryonic stem cells, which demonstrate increased 5hmC at CpG islands associated with bivalent promoters (37).

In addition, our analysis indicates that within the placenta, there are aspects of 5hmC associated with distal regulatory elements. Hydroxymethylation is enriched around regions with poised enhancers, indicated by the presence of H3K4me1, whereas there is a loss of 5hmC within active enhancers. This has again also been demonstrated within the brain (7), suggesting conservation of function across tissues. 5-Formylcytosine (5fmC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC), also intermediaries in active TET demethylation (38), are enriched within poised enhancers, suggesting that these regions are prone to conversion of 5mC to cytosine (39, 40). It is important to note that we highlighted enrichment within poised enhancers based on the presence of systematic hydroxymethylation, which we deemed likely to be stable 5hmC modifications. However, within these regions, that conclusion may not hold true. We did not investigate the kinetics of hydroxymethylation, and should 5mC within these regions have been undergoing demethylation at an elevated rate, we may not have been able to distinguish between this action and stable 5hmC. In contrast to distal enhancer elements, hydroxymethylation did not demonstrate any strong associations with putative transcription factor binding sites outside of NKX3-1. This transcription factor is an androgen regulated homeobox tumor suppressor and has been linked to progression of prostate cancer (41). There is seemingly no link between the function of this transcription factor and the placenta, suggesting that, overall, hydroxymethylation does not play a strong regulatory role around TFBS.

We identified both enrichment and depletion of 5hmC in functionally relevant regions; however, a strong relationship between hydroxymethylation and gene regulation may be found when assessed in relation to gene expression levels. Notably, within genes undergoing transcription, there is a consistent increase in hydroxymethylation levels around the TSS as transcript levels increase. Hydroxymethylation values were binned by sample, by gene so that within each gene, variable expression would be captured across the 20 samples investigated. Although the differences in 5hmC values were nominally small (<1%), the consistency in the difference between tertiles of expression around −1500 to −500 and +500 to +1500 bp, relative to the TSS is notable. This finding is consistent with those in previous studies that highlighted the relationship between hydroxymethylation and gene expression. Among the tissues and cells investigated for this relationship, where 5hmC has been associated with increased expression, are brain (7, 42), chondrocytes (13), and mouse embryonic stem cells (14, 37, 43).

There were only a small number of loci that demonstrated a modest correlation between 5hmC and expression, none of which was significant after multiple-comparison correction. This somewhat weak correlation suggests that regulation of expression by hydroxymethylation is not driven by individual modifications, but likely by minor, additive effects over a larger region. Although this theory may be the case, it is difficult for the 450K arrays to be used for regional assessment, as the coverage (especially when subsetting to loci with systemic hydroxymethylation) is too sparse.

In contrast to the genes we identified as undergoing transcription, the silenced genes presented both 5mC and 5hmC values that were striking outliers. The increase in 5mC within nonexpressed genes followed the commonly held association between DNA methylation and repressed expression. The nearly 8% increase in 5hmC around the TSS of silenced genes, however, was contradictory not only to the general association between hydroxymethylation and increased expression, but to the relationship that we saw within our own data set for expressed genes. This result raises the question of why 5hmC is so much higher in silenced genes, than in those even in the lowest tertile of expression. The high 5hmC value may be an artifact of the elevated 5mC value within these genes. As hydroxymethylation can be a transient intermediate in the demethylation process, what we may be seeing is an increased turnover rate that is related to the elevated methylation and translates into increased hydroxymethylation. It should be noted that because our study focused on term placenta and thus had only a single time point per sample, it is impossible for us to determine whether there is a temporal regulation of 5hmC as a gene transitions from silent to active expression. Follow-up investigation with several time points that would allow for the monitoring of 5hmC as genes transition between expression and repression would help elucidate how this modification regulates transitional regions.

We addressed this question by investigating whether the loci that we identified as displaying systematic hydroxymethylation were associated with genes demonstrating differential expression between placentas collected at the second trimester compared to term. We used publically available data in which 655 genes in total demonstrated differential expression. The original publication (27) identified gene ontology pathways based on those data for the genes differentially expressed between second trimester and term as “pregnancy,” “reproductive physiological process,” “physiological interaction between organisms,” and “interaction between organisms.” We found that the probes associated with these differentially expressed genes were 2 times more likely to be sites of systematic hydroxymethylation than probes not associated with transitional genes. A similar phenomenon has been described in chondrocytes, where there is enrichment for differential 5hmC regions (DhMRs) in genes with variable expression related to aging. In this study (13), DhMRs were identified and compared to findings in a separate study investigating ag3-related gene expression changes (44). Six percent of genes with increased expression and 9% with decreased expression contained DhMRs. It would be ideal to investigate transitional expression and 5hmC in placentas collected from within a single population to ensure that there are no differences caused by sampling; however, our data elicit the question of whether 5hmC is a marker of expression alterations within the genome.

Epigenome-wide mapping studies have given researchers an additional layer of understanding of how exposures may alter gene regulation within the placenta, affecting birth outcomes. However, investigators in studies using BS sequencing to study DNA methylation must now be cognizant that the presence of 5hmC may confound their results. We have highlighted loci within the placenta that demonstrate systematic elevated levels of hydroxymethylation across most of the 23 samples and may represent probes within the 450K array of heightened concern. Although this elevation may be the case, the overall extent of 5hmC across the placenta genome is limited. In addition to investigating the extent of 5hmC, we have described its distribution and potential link to functionally relevant regions. Although additional studies are needed for a more complete understanding of the function of hydroxymethylation within the placenta, our data may serve as an early resource to investigators interested in placental epigenetics.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U. S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Mental Illness (Grant R01MH094609), the NIH National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Grants R01ES022223 and P01 ES022832), and by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA; Grant RD83544201). This article’s contents are solely the responsibility of the grantee, and do not necessarily represent the official views of the EPA. Furthermore, the EPA does not endorse the purchase of any commercial products or services mentioned in the presentation. B.B.G. contributed to the concept and design of the experiment, performed statistical analyses, interpreted the results, and wrote and revised the manuscript. E.A.H. generated the statistical models, performed statistical analyses, interpreted the results, and revised the manuscript. K.C.J. performed statistical analyses, interpreted the results, and revised the manuscript. D.J.G. collected the data and revised the manuscript. D.A.A. collected data and revised the manuscript. B.C.C. contributed to the concept and design of the experiment, interpreted the results, and revised the manuscript. C.J.M. contributed to the concept and design of the experiment, interpreted the results, and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- 5hmC

5-hydroxymethylcytosine

- 5mC

5-methylcytosine

- BS

bisulfite

- DhMR

differential 5hmC region

- FPKM

fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- oxBS

oxybisulfite

- TET

ten-eleven translocation

- TFBS

transcription factor binding site

- TSS

transcription start site

- UCSC

University of California at Santa Cruz

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klose R. J., Bird A. P. (2006) Genomic DNA methylation: the mark and its mediators. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 89–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tahiliani M., Koh K. P., Shen Y., Pastor W. A., Bandukwala H., Brudno Y., Agarwal S., Iyer L. M., Liu D. R., Aravind L., Rao A. (2009) Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science 324, 930–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachman M., Uribe-Lewis S., Yang X., Williams M., Murrell A., Balasubramanian S. (2014) 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine is a predominantly stable DNA modification. Nat. Chem. 6, 1049–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Globisch D., Münzel M., Müller M., Michalakis S., Wagner M., Koch S., Brückl T., Biel M., Carell T. (2010) Tissue distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and search for active demethylation intermediates. PLoS One 5, e15367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nestor C. E., Ottaviano R., Reddington J., Sproul D., Reinhardt D., Dunican D., Katz E., Dixon J. M., Harrison D. J., Meehan R. R. (2012) Tissue type is a major modifier of the 5-hydroxymethylcytosine content of human genes. Genome Res. 22, 467–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stroud H., Feng S., Morey Kinney S., Pradhan S., Jacobsen S. E. (2011) 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine is associated with enhancers and gene bodies in human embryonic stem cells. Genome Biol. 12, R54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wen L., Li X., Yan L., Tan Y., Li R., Zhao Y., Wang Y., Xie J., Zhang Y., Song C., Yu M., Liu X., Zhu P., Li X., Hou Y., Guo H., Wu X., He C., Li R., Tang F., Qiao J. (2014) Whole-genome analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and 5-methylcytosine at base resolution in the human brain. Genome Biol. 15, R49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziller M. J., Gu H., Müller F., Donaghey J., Tsai L. T., Kohlbacher O., De Jager P. L., Rosen E. D., Bennett D. A., Bernstein B. E., Gnirke A., Meissner A. (2013) Charting a dynamic DNA methylation landscape of the human genome. Nature 500, 477–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen B. C., Houseman E. A., Marsit C. J., Zheng S., Wrensch M. R., Wiemels J. L., Nelson H. H., Karagas M. R., Padbury J. F., Bueno R., Sugarbaker D. J., Yeh R. F., Wiencke J. K., Kelsey K. T. (2009) Aging and environmental exposures alter tissue-specific DNA methylation dependent upon CpG island context. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kriaucionis S., Heintz N. (2009) The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science 324, 929–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song C. X., Szulwach K. E., Fu Y., Dai Q., Yi C., Li X., Li Y., Chen C. H., Zhang W., Jian X., Wang J., Zhang L., Looney T. J., Zhang B., Godley L. A., Hicks L. M., Lahn B. T., Jin P., He C. (2011) Selective chemical labeling reveals the genome-wide distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 68–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen L., Tang F. (2014) Genomic distribution and possible functions of DNA hydroxymethylation in the brain. Genomics 104, 341–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor S. E., Li Y. H., Wong W. H., Bhutani N. (2015) Genome-wide mapping of DNA hydroxymethylation in osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67, 2129–2140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pastor W. A., Pape U. J., Huang Y., Henderson H. R., Lister R., Ko M., McLoughlin E. M., Brudno Y., Mahapatra S., Kapranov P., Tahiliani M., Daley G. Q., Liu X. S., Ecker J. R., Milos P. M., Agarwal S., Rao A. (2011) Genome-wide mapping of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in embryonic stem cells. Nature 473, 394–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sui W., Tan Q., Yang M., Yan Q., Lin H., Ou M., Xue W., Chen J., Zou T., Jing H., Guo L., Cao C., Sun Y., Cui Z., Dai Y. (2015) Genome-wide analysis of 5-hmC in the peripheral blood of systemic lupus erythematosus patients using an hMeDIP-chip. Int. J. Mol. Med. 35, 1467–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman C. G., Mariani C. J., Wu F., Meckel K., Butun F., Chuang A., Madzo J., Bissonette M. B., Kwon J. H., Godley L. A. (2015) TET-catalyzed 5-hydroxymethylcytosine regulates gene expression in differentiating colonocytes and colon cancer. Sci. Rep. 5, 17568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maccani M. A., Marsit C. J. (2009) Epigenetics in the placenta. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 62, 78–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green B. B., Marsit C. J. (2015) Select prenatal environmental exposures and subsequent alterations of gene-specific and repetitive element DNA methylation in fetal tissues. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2, 126–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson W. P., Price E. M. (2015) The human placental methylome. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 5, a023044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piyasena C., Reynolds R. M., Khulan B., Seckl J. R., Menon G., and Drake A. J. (2015) Placental 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine patterns associate with size at birth. Epigenetics 10, 692–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart S. K., Morris T. J., Guilhamon P., Bulstrode H., Bachman M., Balasubramanian S., Beck S. (2015) oxBS-450K: a method for analysing hydroxymethylation using 450K BeadChips. Methods 72, 9–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y. A., Lemire M., Choufani S., Butcher D. T., Grafodatskaya D., Zanke B. W., Gallinger S., Hudson T. J., Weksberg R. (2013) Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics 8, 203–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim D., Pertea G., Trapnell C., Pimentel H., Kelley R., Salzberg S. L. (2013) TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14, R36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trapnell C., Williams B. A., Pertea G., Mortazavi A., Kwan G., van Baren M. J., Salzberg S. L., Wold B. J., Pachter L. (2010) Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 511–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts A., Trapnell C., Donaghey J., Rinn J. L., Pachter L. (2011) Improving RNA-Seq expression estimates by correcting for fragment bias. Genome Biol. 12, R22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu M., Hon G. C., Szulwach K. E., Song C. X., Zhang L., Kim A., Li X., Dai Q., Shen Y., Park B., Min J. H., Jin P., Ren B., He C. (2012) Base-resolution analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the mammalian genome. Cell 149, 1368–1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mikheev A. M., Nabekura T., Kaddoumi A., Bammler T. K., Govindarajan R., Hebert M. F., Unadkat J. D. (2008) Profiling gene expression in human placentae of different gestational ages: an OPRU Network and UW SCOR Study. Reprod. Sci. 15, 866–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bibikova M., Barnes B., Tsan C., Ho V., Klotzle B., Le J. M., Delano D., Zhang L., Schroth G. P., Gunderson K. L., Fan J. B., Shen R. (2011) High density DNA methylation array with single CpG site resolution. Genomics 98, 288–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nestor C., Ruzov A., Meehan R., Dunican D. (2010) Enzymatic approaches and bisulfite sequencing cannot distinguish between 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in DNA. Biotechniques 48, 317–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Field S. F., Beraldi D., Bachman M., Stewart S. K., Beck S., Balasubramanian S. (2015) Accurate measurement of 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in human cerebellum DNA by oxidative bisulfite on an array (OxBS-array). PLoS One 10, e0118202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Binder A. M., LaRocca J., Lesseur C., Marsit C. J., Michels K. B. (2015) Epigenome-wide and transcriptome-wide analyses reveal gestational diabetes is associated with alterations in the human leukocyte antigen complex. Clin. Epigenetics 7, 79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maccani J. Z., Koestler D. C., Houseman E. A., Armstrong D. A., Marsit C. J., Kelsey K. T. (2015) DNA methylation changes in the placenta are associated with fetal manganese exposure. Reprod. Toxicol. 57, 43–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maccani J. Z., Koestler D. C., Lester B., Houseman E. A., Armstrong D. A., Kelsey K. T., Marsit C. J. (2015) Placental DNA methylation related to both infant toenail mercury and adverse neurobehavioral outcomes. Environ. Health Perspect. 123, 723–729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finer S., Mathews C., Lowe R., Smart M., Hillman S., Foo L., Sinha A., Williams D., Rakyan V. K., Hitman G. A. (2015) Maternal gestational diabetes is associated with genome-wide DNA methylation variation in placenta and cord blood of exposed offspring. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 3021–3029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruchat S. M., Houde A. A., Voisin G., St-Pierre J., Perron P., Baillargeon J. P., Gaudet D., Hivert M. F., Brisson D., Bouchard L. (2013) Gestational diabetes mellitus epigenetically affects genes predominantly involved in metabolic diseases. Epigenetics 8, 935–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lister R., Mukamel E. A., Nery J. R., Urich M., Puddifoot C. A., Johnson N. D., Lucero J., Huang Y., Dwork A. J., Schultz M. D., Yu M., Tonti-Filippini J., Heyn H., Hu S., Wu J. C., Rao A., Esteller M., He C., Haghighi F. G., Sejnowski T. J., Behrens M. M., Ecker J. R. (2013) Global epigenomic reconfiguration during mammalian brain development. Science 341, 1237905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu H., D’Alessio A. C., Ito S., Wang Z., Cui K., Zhao K., Sun Y. E., Zhang Y. (2011) Genome-wide analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine distribution reveals its dual function in transcriptional regulation in mouse embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 25, 679–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ito S., Shen L., Dai Q., Wu S. C., Collins L. B., Swenberg J. A., He C., Zhang Y. (2011) Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science 333, 1300–1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen L., Wu H., Diep D., Yamaguchi S., D’Alessio A. C., Fung H. L., Zhang K., Zhang Y. (2013) Genome-wide analysis reveals TET- and TDG-dependent 5-methylcytosine oxidation dynamics. Cell 153, 692–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song C.-X., Szulwach K. E., Dai Q., Fu Y., Mao S. Q., Lin L., Street C., Li Y., Poidevin M., Wu H., Gao J., Liu P., Li L., Xu G. L., Jin P., He C. (2013) Genome-wide profiling of 5-formylcytosine reveals its roles in epigenetic priming. Cell 153, 678–691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gelmann E. P., Bowen C., Bubendorf L. (2003) Expression of NKX3.1 in normal and malignant tissues. Prostate 55, 111–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mellén M., Ayata P., Dewell S., Kriaucionis S., Heintz N. (2012) MeCP2 binds to 5hmC enriched within active genes and accessible chromatin in the nervous system. Cell 151, 1417–1430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu Y., Wu F., Tan L., Kong L., Xiong L., Deng J., Barbera A. J., Zheng L., Zhang H., Huang S., Min J., Nicholson T., Chen T., Xu G., Shi Y., Zhang K., Shi Y. G. (2011) Genome-wide regulation of 5hmC, 5mC, and gene expression by Tet1 hydroxylase in mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell 42, 451–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peffers M., Liu X., Clegg P. (2013) Transcriptomic signatures in cartilage ageing. Arthritis Res. Ther. 15, R98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]