ABSTRACT

Background/Purpose

The McKenzie Method of mechanical diagnosis and therapy (MDT) is supported in the literature as a valid and reliable approach to the management of spine injuries. It can also be applied to the peripheral joints, but has not been explored through research to the same extent. This method sub-classifies an injury based on tissue response to mechanical loading and repeated motion testing, with directional preferences identified in the exam used to guide treatment. The purpose of this case report is to demonstrate the assessment, intervention, and clinical outcomes of a subject classified as having a shoulder derangement syndrome using MDT methodology.

Case Description

The subject was a 52-year-old female with a four-week history of insidious onset left shoulder pain, referred to physical therapy with a medical diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis. She presented with pain (4-7/10 on the visual analog scale [VAS]) and decreased shoulder range of motion that limited her activities of daily living and work capabilities (Upper Extremity Functional Index (UEFI) score: 55/80). Active and passive ranges of motion (A/PROM) were limited in all planes. Repeated motion testing was performed, with an immediate reduction in pain and increased shoulder motion in all planes following repeated shoulder extension. As a result, her MDT classification was determined to be derangement syndrome. Treatment involved specific exercises, primarily repeated motions, identified as symptom alleviating during the evaluation process.

Outcomes

The subject demonstrated significant improvements in the UEFI (66/80), VAS (0-2/10), and ROM within six visits over eight weeks. At the conclusion of treatment, A/PROM was observed to be equal to the R shoulder without pain.

Discussion

This subject demonstrated improved symptoms and functional abilities following evaluation and treatment using MDT methodology. While a cause-effect relationship cannot be determined with a single case, MDT methodology may be a useful approach to the examination, and potentially management, of patients with shoulder pain. This method offers a patient specific approach to treating the shoulder, particularly when the pathoanatomic structure affected is unclear.

Level of Evidence

4

Keywords: Adhesive capsulitis, McKenzie, Mechanical Diagnosis and Treatment

BACKGROUND/PURPOSE

It has been reported that the number of individuals with peripheral joint injuries far exceed those that require treatment for injuries of the spine.1 The prevalence of these peripheral joint injuries ranges from 6.7 to 46.7% per year in the general population, demonstrating the importance of finding effective evaluation and treatment methods.2 The literature reveals that most therapists commonly use specialized orthopedic testing procedures applied to a pathoanatomic model to diagnose shoulder injuries.3 However, arriving at a specific pathoanatomic diagnosis is challenging due to questionable reliability and validity of specialized orthopedic testing.4-18 De Winter et al reported that in the diagnosis of different shoulder injuries, including adhesive capsulitis, the kappa value for correct diagnosis was 0.45 (95% confidence interval 0.37,0.54),10 demonstrating only low-to- moderate reliability.19 Failure to correlate the exact anatomical structure with the patient's presentation can complicate the diagnosis and treatment process.

Traditional treatments delivered for adhesive capsulitis based on pathoanatomic findings include corticosteroid injections, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, manipulations, and therapeutic exercise.1 The literature supports that exercise is much more effective than either modalities or medications.1,20-22 However, 40% of individuals treated with traditional therapies continue to experience pain and loss of ROM23 after discharge, suggesting that current treatment methods may be suboptimal.1 Assigning a sub-classification based on the tissue's mechanical response to loading, rather than pathoanatomic diagnosis, may offer a viable treatment approach to address the continued pain and stiffness in this population.24-26

Application of the McKenzie method (MDT) has become widely accepted as a valid form of evaluation and treatment for the spine, and has demonstrated a high degree of inter-rater reliability when identifying a mechanical classification27,28 with trained therapists demonstrating approximately 92% agreement on classification.29 When these classifications were used to guide treatment, chronic pain and disability were improved in patients with spine injuries that received interventions based on directional preference.24,26

It has been suggested that MDT assessment methodology could also be applied effectively to peripheral joints by classifying them into posture, dysfunction, or derangement syndromes.1 The McKenzie method is a mechanical sub-classification system based on the patient history and the response to repeated motions and positioning, rather than attempting to identify the exact pathoanatomic structure.1 An MDT trained therapist uses the assessment to classify the patient based on their responses during movement, with repeated motion testing used to determine the patient's mechanical classification and treatment.29

Derangement syndrome is a classification not utilized by any other evaluation and treatment approach.1 It is defined as an internal disruption or displacement of tissue, which then mechanically deforms outer innervated structures.1,3,30 The resulting pain is then referred peripherally depending upon the degree of internal displacement. When the tissue is displaced to a lesser degree pain is intermittent; however, larger displacements may cause constant pain. Individuals with this syndrome can experience quick changes in symptoms and mechanical presentation as a result of repeated motions. A directional preference is found when movement(s) in a specific direction reduces the patient's report of pain. It must then be determined if this reduction is maintained over time, or if it will continue to re-occur. Conversely, motions that open the joint space may temporarily decrease pain, but may displace the tissue even further.1 Outcomes with this type of treatment have been very successful when applied to the spine. However, it appears that there are currently only two case reports that demonstrate the effectiveness of MDT on the shoulder complex.3,30

The purpose of this case report is to detail the use of MDT principles in the assessment and treatment of an individual with shoulder pain. More specifically, this case report details the process used to identify a directional preference during evaluation, with subsequent treatment based on this response.

HISTORY AND REVIEW OF SYSTEMS

The subject was a 52-year-old female who reported pain and decreased ROM after striking her left shoulder on a refrigerator four weeks prior to the initial evaluation. Radiographs were negative, and her orthopedic physician provided a diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis. She was subsequently referred to physical therapy for ROM and strengthening. The subject reported intermittent symptoms, made worse with overhead motions, twisting doorknobs, and opening jars. Significant functional limitations included: limited ability to perform her usual work hanging wallpaper, limited ability to perform volunteer work due to pain with lifting, and limited ability to care for her grandchildren.

A thorough systems review was conducted (Table 1).

Table 1.

Systems Review During Subject Examination.

| Cardiovascular/Pulmonary | |

| Normal | |

| Musculoskeletal | |

| Impaired | Gross range of motion (ROM) impairments in left shoulder with pain. |

| 5/5 Strength for all shoulder motions bilaterally; however, pain produced with abduction, internal rotation (IR), and external rotation (ER) on the left. | |

| 5/5 Strength for all elbow motions bilaterally; pain with left elbow flexion, extension, pronation, and supination | |

| Neuromuscular | |

| Normal | |

| Integumentary | |

| Normal | |

| Communication | |

| Normal | |

Overall, the subject reported good health, and denied any previous orthopedic injuries. Her main goal for therapy was to return to work, complete ADLs, and complete volunteer work without aggravating symptoms or needing assistance.

The subject provided written informed consent for participation in this case report, and for any photography or videography associated with this report.

CLINICAL IMPRESSION 1

Following the subjective history and systems review, it was hypothesized that the subject presented with left shoulder adhesive capsulitis, which is classified in the MDT system as a dysfunction. This was based upon her restricted left shoulder ROM in all directions with pain, consistent with ICD 10 criteria for adhesive capsulitis:31 reports of pain in the shoulder exacerbated by activity and feeling of stiffness, with examination criteria of reduced passive range of GH motion >30° in two planes.32,33 However, loss of ROM and pain are present with a variety of diagnoses; therefore a thorough evaluation was planned. Additionally, pain with elbow motions indicated possible involvement of the long head of the biceps tendon. Further tests/measures to rule in/out other possible conditions included the Crank test, Empty-Can Test, Hawkins-Kennedy Test, and Speed's Test.

It was planned to evaluate the subject using McKenzie methodology. This approach involves identifying the body area involved, pain levels, how long the pain had been present, whether the symptoms were constant or intermittent, and if there were any positions or motions that changed the symptoms. After observation of posture, palpation, ROM/strength testing, and special testing, repeated motion testing commences. The evaluation focuses on identification of a concordant sign, defined as a movement or position that increases or reproduces the subject's symptoms consistently. The subject's report of how repeated motions in various directions affect the concordant sign determines the mechanical diagnostic classification, which in turn guides treatment.

EXAMINATION

The subject completed the Upper Extremity Functional Index (UEFI), and received a score of 55/80, indicating moderate disability. She reported pain that ranged from 4-7/10 on the VAS. After observational analysis and palpation was conducted, a gross AROM and strength assessment was performed. Deficits were noted in AROM and strength of the left upper extremity (pain produced), leading to goniometric measurements of PROM and evaluation for end-feel and restrictions. PROM measurements can be seen in Table 2. All glenohumeral joint motions on the left presented with firm (capsular) end feel and pain. The following diagnostic tests were performed to evaluate for impingement, labral and/or muscular pathology: Crank Test (negative), Empty Can Test (positive), Speed's Test (positive), and Hawkins-Kennedy Test (positive).

Table 2.

Passive Range of Motion Measurements (Initial Examination).

| Right | Left | |

|---|---|---|

| Abduction | 178° | 152° |

| Flexion | 180° | 155° |

| External Rotation | 101° | 70° |

| Internal rotation | 56° | 62° |

Repeated motion testing was performed as per MDT methodology. The subject performed two sets of 20 repetitions in shoulder flexion, shoulder external rotation, shoulder extension, and scapular retraction, and reported how the motions affected her symptoms during and after the test, with particular interest on change in the concordant signs (Table 3). Rapid improvements in ROM, pain, and her concordant signs were observed following scapular retractions and shoulder extension.

Table 3.

MDT Repeated Motion Testing.

| Repeated Motion Testing | Initial Evaluation Results | Final Evaluation Results |

|---|---|---|

| Scapular Retractions | During: pain decreased, A/PROM increased | Full A/PROM, no pain |

| After: better A/PROM/pain (1/10) | ||

| Shoulder Flexion | During: NE pain, A/PROM increased | Not tested |

| After: NE pain/A/PROM | ||

| Shoulder ER | During: pain increased, NE A/PROM | Not tested |

| After: A/PROM/pain worse after | ||

| Shoulder Extension | During: pain decreased, A/PROM increased | Full A/PROM, no pain |

| After: Better A/PROM/pain (1/10) | ||

| Mechanical Diagnosis Hypothesis | ||

| Derangement Syndrome | ||

AROM = active range of motion, PROM=passive range of motion NE = no effect, ER = external rotation

CLINICAL IMPRESSION 2

The primary impairments identified during the examination were left shoulder pain and loss of ROM that prevented participation in volunteer activities, work, and self-care activities. At this point in the examination, the pathoanatomic differential diagnosis consisted of adhesive capsulitis, impingement, and/or a rotator cuff tear. Differential diagnosis for MDT classification included articular dysfunction, contractile dysfunction, and derangement.

The subject presented with generalized tenderness to palpation of the anterior left glenohumeral joint as well as impaired posture (forward head, rounded shoulders). A positive Empty Can test indicated possible supraspinatus pathology, Hawkins-Kennedy test possible shoulder impingement, and Speed's test indicated possible biceps LH pathology. A gross strength assessment revealed full strength for all shoulder motions with pain upon resistance in all shoulder motions, indicating possible muscular pathology. However, impingement findings and painful resisted tests are not uncommon with a diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis.34 PROM was decreased and painful with firm-end feel demonstrating probable capsular pathology. Following performance of scapular retractions and shoulder extension during repeated motion testing (two sets of 20 repetitions for each motion) her ROM and pain levels for all shoulder motions demonstrated immediate improvement. The mechanical diagnosis of a derangement was assigned to the subject based on the rapid change in her symptoms during repeated movements, despite her medical diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis.

Given the subject's few co-morbidities, intermittent symptoms, and excellent response to repetitive motion testing, she was an excellent candidate for physical therapy. Additionally, individuals with a diagnosis of derangement syndrome have been reported to generally demonstrate a very quick response to therapy.1,3,25 She was very motivated, which indicated that she would be very compliant with her HEP. As a result, it was expected that she would make a full recovery in a short period of time.

Based on the mechanical diagnosis, the subject was sent home with scapular retractions and shoulder extension exercises (two sets of 20 repetitions of each exercise, four to five times per day) to continue treatment. It was agreed that the subject would attend therapy once per week, with overall therapy goals to increase ROM to be equal bilaterally, and to decrease pain.

INTERVENTIONS

The subject was provided with a thorough explanation of her condition (adhesive capsulitis), and mechanical classification (derangement), and then goals were established for physical therapy. Given her positive initial reaction to therapy, it was decided that she did not require outside referral for further medical intervention, and was appropriate for physical therapy management.

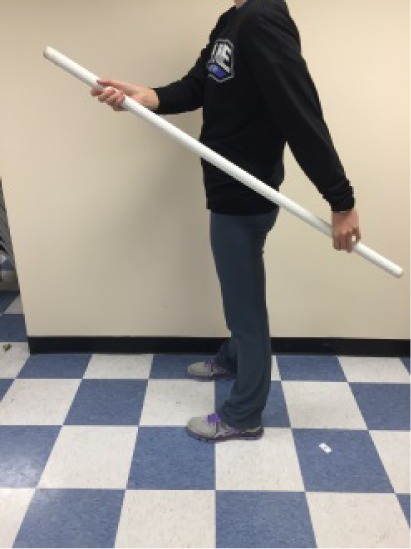

As described above, shoulder extension and scapular retractions decreased the concordant signs, increased A/PROM, and decreased pain levels to 1/10 during the initial evaluation. Therefore, interventions were designed to favor these movements. The upper body ergometer (Cybex, Bayshore, NY) was performed as a warm up to increase synovial fluid and blood flow, and the subject then completed standing scapular retractions followed by shoulder extension with a dowel (Appendix 1). Standing rowing with red tubing (Theraband, Akron, OH) was added for inter-scapular strengthening and postural re-education (Appendix 1).35 It was expected that improved activation and strength of the interξ-scapular musculature and postural re-education would improve scapula-humeral rhythm, shoulder biomechanics, and posture.36 Finally, the subject was given pictures and demonstrations to convey therapy and HEP exercises, as this was her preference. This included the subject performing the given stretches four to five times throughout the day (two sets, 20 repetitions). She was also advised to avoid other potentially provocative shoulder motions.

Due to continued improvements in ROM, pain, and function over the following sessions, it was determined that the correct directional preference had been identified. Treatment was then progressed according to MDT methodology for treatment of derangements. Once the subject could perform challenging activities without aggravating symptoms, exercises were progressed to include all planes of motion while continuing her previous exercise program (shoulder extensions, scapular retractions). It should be noted that exercises incorporating external rotation (ER) were added in the treatment program at visit 4, causing the subject's symptoms to become aggravated. The subject's symptoms quickly returned to baseline after external rotation was removed as an intervention on visit 5, with a subsequent improvement of ER range of motion to normal by visit 6. The subject was instructed to continue the initial exercises after discharge to prevent the derangement from re-occurring.

OUTCOMES

At discharge the subject had met or exceeded all PT goals, with the exception of the UEFI score. However, she did show a clinically significant improvement of 11 points the UEFI [MCID 9-10 points].37 PROM on the involved side was equal to the unaffected side with firm end feel and no pain. VAS scores revealed that the subject experienced only mild pain (2/10) during overhead activities. All special tests (including the Hawkins-Kennedy, Empty Can and Speed's) were negative, demonstrating resolution of her symptoms throughout the treatment process. Since pain was infrequent, and continued to diminish, the subject was advised to continue with her home exercise program. Initial and final examination findings are detailed in Table 4, and Figures 1-3 detail changes in ROM and pain that occurred at each visit.

Table 4.

Initial vs. Final Outcome Results.

| Outcome Measurements | Initial Visit | Final Visit | Goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| UEFI (function) | 55/80 | 66/80 | 75/80 (improved but not met) ✗ |

| VAS (pain) | Current: 4/10 | Current: 0/10 | 0/10 (goal met) ✓ |

| 24 hour max: 7/10 | 24 hour max: 2/10 | No goal made specifically about this | |

| Empty Can Test | Positive | Negative | Goal met ✓ |

| Hawkins-Kennedy Test | Positive | Negative | Goal met ✓ |

| Speed's Test | Positive | Negative | Goal met ✓ |

| Gross Strength Assessment | 5/5 all shoulder motions (abduction, IR, ER painful) | 5/5 all shoulder motions (mild pain only with ER) | No pain with resisted motions (goal met) ✓ |

| 5/5 all elbow motions (flexion, extension, pronation, supination painful) | 5/5 all elbow motions | 0/10 pain with resisted motions (goal met) ✓ | |

| AROM | Gross limitations all shoulder motions with pain | AROM equal bilaterally with no pain | AROM on left equal to right with 0/10 pain (goal met) ✓ |

| PROM | Right: 178 abduction 180 flexion 101 ER 56 IR (firm end feel) |

Right: 178 abduction 180 flexion 101 ER 56 IR (firm end feel) |

No goal addressed this |

| Left: 152 abduction 155 flexion 70 ER 62 IR (pain, firm end feel) |

Left: 177 abduction 178 flexion 99 ER 62 IR (firm end feel, pain-free) |

Full PROM (when compared to right) with 0/10 pain (goal met) ✓ |

UEFI=Upper Extremity Functional Index, VAS = visual analog scale for pain, AROM=active range of motion, PROM=passive range of motion, ER=external rotation, IR=internal rotation

Figure 1.

Range of motion at initial evaluation and discharge, compared to uninvolved side.

Figure 3.

Pain measured on visual analog scale at each treatment session.

Figure 2.

Range of motion at initial evaluation and discharge, compared to uninvolved side.

DISCUSSION

Given the questionable sensitivity and specificity of pathoanatomic models for diagnosis and treatment of shoulder pathology, a model based upon patient response may allow for more accurate treatment of individual patients. Considering the moderate19 levels of sensitivity and specificity reported for the diagnostic tests used with this subject: Empty Can Test (SN 0.69-0.78, SP 0.52-0.62)11, Speed's Test (SN 0.48, SP 0.55)38 and Hawkins-Kennedy Test (SN 0.79, SP 0.59)4 as well as research demonstrating that structures other than rotator cuff tendons are impinged during impingement testing,8 and the diagnostic uncertainty of adhesive capsulitis, an individualized approach based upon symptom behavior appears to be a viable alternative to pathoanatomic diagnosis. The literature supports the reliability of this system among trained clinicians, with 85.5% diagnosis categories remaining consistent throughout treatment.1,29,39,40 Evaluation to determine specific mechanical behaviors allows the therapist to select treatments that demonstrate symptom alleviation, limiting the need for determination of a specific pathoanatomic diagnosis. This may be particularly beneficial when treating adhesive capsulitis, as this condition and its comorbidities are frequently misdiagnosed.10,41 Although it is possible that this subject was misdiagnosed as having adhesive capsulitis, this remains questionable as adhesive capsulitis is primarily a clinical diagnosis,41 and the subjects symptoms were consistent with the ICD 10 criteria as described earlier.31-33 Authors have concluded that the diagnosis of idiopathic versus secondary adhesive capsulitis may be elusive.41 Regardless of the actual pathoanatomic diagnosis, in this case the subject's physical therapy treatment was effective as it was tailored to specific responses to movement rather than a medical diagnosis.

With the application of MDT methodology, it was determined that the subject's condition was not a shoulder dysfunction (the mechanical classification for adhesive capsulitis) but rather a derangement based upon the subject's rapid symptomatic improvement following repeated motions. Derangement has previously been identified as the most common cause of shoulder pain identified by MDT practitioners.42 Specifically, this subject recovered following repeated shoulder extension. This is in agreement with the case series of Aytona and Dudley,3 who found that there was a trend towards recovering following repeated extension in subjects with shoulder derangement. A recent study also identified extension as the most common directional preference in the shoulder.37 This finding requires further study to confirm its relevance.

There is conjecture about the pathoanatomic basis of obstructed movement in peripheral joints. In a cadaveric study, it was revealed that intra-articular intrusions (deformable space fillers composed of fat pads and fibroadipose meniscoids) could proliferate within joints.43 It is thought that cartilage fragments, joint capsule, a portion of the labrum, or any other component of the joint can become interposed between the joint surfaces causing blocked movement and abnormal stress on peri-articular structures.1 Pain is derived from deformation of the joint capsule and supporting ligaments when the normal resting position is disturbed. These have been suggested as a potential cause for derangement in the extremities, but this still requires much investigation.3,43 Therefore, it is proposed that due to the nature of derangements, performing exercises that go against the identified directional preference can prevent the tissue from re-aligning itself, or can cause the tissue to become displaced even further.1,25,30 This was seen during the treatment of this subject when stretches incorporating ER were added prematurely on visit four with aggravating affects, which may have also interfered with subject outcomes at discharge, although the subject's symptoms returned to baseline rapidly after discontinuing ER on visit five.

There are several limitations of this case report that merit discussion. This report does not attempt to demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship between the use of MDT methodology and successful outcomes for individuals’ that are being treated with injuries to the shoulder complex. During the examination of the subject, the therapist did not test accessory motions of the shoulder complex, which is a common practice when dealing with adhesive capsulitis. Therefore, it is not known if joint mobilization would have had specific benefit for this subject; however, the capsular end feels identified during examination would suggest that this may have been an appropriate alternative. Furthermore, integrating motions that favored external rotation into the exercise program, which is also common practice in treatment of adhesive capsulitis, had a short term detrimental effect with this subject. While in this case it appears that avoiding external rotation exercises was beneficial, this may not be the case for other patients diagnosed with adhesive capsulitis. Although the subject demonstrated rapid improvements in symptoms throughout the duration of treatment, these limitations need to be considered prior to the application of this methodology.

CONCLUSIONS

The outcomes of this case report suggest that the use of MDT techniques can be effective in the treatment of shoulder pathology. The ability to establish a cause-and-effect relationship is limited as this is a report of a single case, particularly as there is no long-term follow-up available. However, the rapid improvements that were observed suggest that the use of MDT methodology may be a useful approach to the examination, and potentially management, of patients with shoulder pain. More research is required comparing the outcomes of individuals treated with MDT methodology compared to traditional therapy methods, and to determine if this is a valid approach for treatment of the extremities. Overall, this method offers a patient specific approach to treating the shoulder, particularly when the pathoanatomic structure affected is unclear.

Appendix 1.

| Intervention | Explanation | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

Shoulder Extension

|

|

Performed 4-5 times per day (HEP), and throughout therapy sessions. Instructed to perform during times when shoulder felt stiff and sore (post-aggravating activities). |

Scapular retractions

|

|

Performed 4-5 times per day (HEP), and throughout therapy sessions. Instructed to perform when symptoms were aggravated or when sitting with poor posture for long periods. |

| Upper Body Ergometer (UBE) |

|

Performed for 8 minutes at the beginning of every physical therapy session. |

| Standing Rows with scapular retractions with elastic resistance |

|

Performed 2-3 times per day at home, and once during the physical therapy session. |

REFERENCES

- 1.May S McKenzie R. The Human Extremities Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy. Waikanae, Wellington, New Zealand:: Spinal Publications New Zealand Ltd.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luime JJ Koes B Hendrikge IJ Burdof A Verhagen AP Miedema HS, et al. Prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain in the general population; A systematic review. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33(2):73-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aytona MC Dudley K. Rapid resolution of chronic shoulder pain classified as derangement using the McKenzie method: a case series. J Man Manip Ther. 2013; 21(4):207-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hegedus EJ Goode A Campbell S Morin A Tamaddoni M Moorman CT 3rd Cook C. Physical examination tests of the shoulder: A systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests. Br J Sports Med. 2008; 42(2):80-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuipers T Van der Windt D Van der Heijden J Bouter LR. A systematic review of prognostic cohort studies on shoulder disorders. Pain. 2004; 109:420-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.May S Larsenk C Littlewood C Lomas D Saad M. Reliability of physical exam tests used in the assessment of a patient with shoulder problems a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2010; 96:179-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munro W Healy R. The validity and accuracy of clinical tests used to detect labral pathology of the shoulder-a systematic review. Man Ther. 2009; 14(2):119-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tucker S Taylor NF Green RA. Anatomical validity of the Hawkins-Kennedy test-a pilot study. Man Ther. 2011; 16(4):399-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Kampen DA van den Berg T van der Woude HJ Castelein RM Scholtes VA Terwee CB Willems WJ. The diagnostic value of the compilation of patient characteristics, history, and clinical shoulder tests for the diagnosis of rotator cuff tear. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014; 9:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Winter AF Jans MP Scholten RJ Deville W van Schaardenburg D bouter LM. Diagnostic classification of shoulder disorders: interobserver agreement and determinants of disagreement. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999; 58(5):272-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Algunaee M Galvin R Fahey T. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for subacromial impingement syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012; 93(2):229-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Codaogen A Laslett M Hing W McNair P Williams M. Interexaminer reliability of orthopaedic special tests used in the assessment of shoulder pain. Man Ther. 2011; 16(2):131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansson K Ivarson S. Intra- and interexaminer reliability of four manual shoulder maneuvers used to identify subacromial pain. Man Ther. 2009; 14(2):231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nada R Gupta S Kanapathipillai P Liow RY Rangan A. An assessment of interexaminer reliability of clinical tests for subacromial impingement and rotator cuff integrity. European J of Surgery and Traumatology. 2008; 18:495-500. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ostor AJK Richards CA Prevost AT Hazleman BA Speed CA. Inter-rater reliability of clinical tests for rotator cuff lesions. Ann Rheum Dis. , 2004; 63:1288-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norregaard J Krogsgaard MR Lorenzen T Jensen EM. Diagnosing patients with longstanding shoulder joint pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002; 61:646-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Razmjou H Holtby R Myhr TP. Pain provocative shoulder tests: reliability and validity of the impingement tests. Physiotherapy Canada. 2004; 56(4):229-36. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsworth MK Doukas WC Murphy KP Mielcarek BJ Michener LA. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of history and physical examination for diagnosing glenoid labral tears. Am J Sports Med. 2008; 36(1):162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Portney LG Watkins M. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. 3 ed. Saddle River, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchbinder R Green S Yood JM. Corticosteroid injections for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain TK Sharma N. The effectiveness of physiotherapeutic interventions in treatment of frozen shoulder/adhesive capsulitis: a systematic review. Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2014;27(3):247-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Page M Green S Kramer S Johnston R McBain B Chau M Buchbinder R. Manual Therapy and Exercise for Adhesive Capsulitis (frozen Shoulder). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaffer B Tibone J Kerlan RK. Frozen shoulder. A long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74(5):738-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edmond SL Werneke MW Hart DL. Association between centralization, depression, somatization, and disability among patients with nonspecific low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;30(12):801-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kidd J. Treatment of shoulder pain utilizing mechanical diagnosis and therapy principles. J Man Manip Ther. 2013;21(3):168-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Werneke MW Hart DL Cutrone G Oliver D McGill T Weinberg J Grigsby D Oswald W Ward J. Association between directional preference and centralization in patients with low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(1):22-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petersen T Christensen R Juhl C. Predicting a clinically important outcome in patients with low back pain following McKenzie therapy or spinal manipulation: a stratified analysis in a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16(74). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersen T Larsen K Nordsteen J Olsen S Fournier G Jacobsen S. The McKenzie Method compared with manipulation when used adjunctive to information and advice in low back pain patients presenting with centralization or peripheralization: A randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2011; 36(24):1999-2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.May S Ross J. The McKenzie classification system in the extremities: a reliability study using McKenzie assessment forms and experienced clinicians. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2009; 32:556-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aina A May S. Case report-a shoulder derangement. Man Ther. 2005; 10:159-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juel NG Natvig B. Shoulder diagnoses in secondary care, a one year cohort. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2014;15:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tveita EK Tariq R Sesseng S Juel NG Bautz-Holter E. Hydrodilatation, corticosteroids and adhesive capsulitis: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008; 9:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hand GC Athanasou N Matthews T Carr AJ The pathology of frozen shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:928-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koester MC George MS Kuhn JE. Shoulder impingement syndrome. Am J Med, 2005;118(5):452-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hrysomallis C, Effectiveness of strengthening and stretching exercises for the postural correction of abducted scapulae. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(2):567-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bullock MP Foster N Wright CC. Shoulder impingement: the effect of sitting posture on shoulder pain and range of motion. Man Ther. 2005;10(1):28-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hefford C Abbott JH Arnold R Baxter GD. The patient-specific functional scale: Validity, reliability, and responsiveness in patients with upper extremity musculoskeletal problems. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012; 42(2):56-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cook C Beaty S Kissenberth MJ Siffri P Pill SG Hawkins RJ. Diagnostic accuracy of five orthopedic clinical tests for diagnosis of superior labrum anterior posterior (SLAP) lesions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):13-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.May S Greasley A Reeve S Withers S. Expert therapists use specific clinical reasoning processes in the assessment and management of patients with shoulder pain: a qualitative study. Aust J Physiotherapy. 2008; 54(4):261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abady AH Rosedale R Overend TJ Chesworth BM Rotundi MA. Interexaminer reliability of diplomats in the mechanical diagnosis and therapy system in assessing patients with shoulder pain. J Man Manip Ther. 2014; 22(4):199-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loeffler BJ Brown SL D’Alessandro DF Fleischli JE Connor PM. Incidence of false positive rotator cuff pathology in MRIs of patients with adhesive capsulitis. Orthopedics. 2011; 34(5):362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.May SJ Rosedale R. A survey of the McKenzie classification system in the extremities: prevalence of the mechanical syndromes and preferred loading strategy. Phys Ther. 2012; 92:1175-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mercer SR Bogduk N. Intra-articular inclusions of the elbow joint complex. Clin Anat. 2007;20:668-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]