Abstract

Microfluidic devices can sort immunomagnetically labeled cells with sensitivity and specificity much greater than that of conventional methods, primarily because the size of microfluidic channels and micro-scale magnets can be matched to that of individual cells. However, these small feature sizes come at the expense of limited throughput (ϕ < 5 mL h−1) and susceptibility to clogging, which have hindered current microfluidic technology from processing relevant volumes of clinical samples, e.g. V > 10 mL whole blood. Here, we report a new approach to micromagnetic sorting that can achieve highly specific cell separation in unprocessed complex samples at a throughput (ϕ > 100 mL h−1) 100× greater than that of conventional microfluidics. To achieve this goal, we have devised a new approach to micromagnetic sorting, the magnetic nickel iron electroformed trap (MagNET), which enables high flow rates by having millions of micromagnetic traps operate in parallel. Our design rotates the conventional microfluidic approach by 90° to form magnetic traps at the edges of pores instead of in channels, enabling millions of the magnetic traps to be incorporated into a centimeter sized device. Unlike previous work, where magnetic structures were defined using conventional microfabrication, we take inspiration from soft lithography and create a master from which many replica electroformed magnetic micropore devices can be economically manufactured. These free-standing 12 µm thick permalloy (Ni80Fe20) films contain micropores of arbitrary shape and position, allowing the device to be tailored for maximal capture efficiency and throughput. We demonstrate MagNET's capabilities by fabricating devices with both circular and rectangular pores and use these devices to rapidly (ϕ = 180 mL h−1) and specifically sort rare tumor cells from white blood cells.

Introduction

The isolation of specific populations of cells, such as stem cells, pathogens, or circulating tumor cells (CTCs), from complex biological fluids is an emerging methodology that holds enormous potential for detecting, monitoring, and studying a wide variety of diseases.1–4 The use of magnetic fields to separate cells labeled with magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) has shown particular promise because it can achieve highly selective sorting even in complex biological media, due to the inherently negligible magnetism of biological samples compared to MNP labeled cells.5–9 Moreover, platforms that use micro-scale structures, where the dimensions of the microfluidic channels and the micrometer-scale magnets can be designed to match those of the targeted cells, have been harnessed for highly selective sorting of rare cells. However, conventional microfluidic geometries where immunomagnetically labelled cells travel through microfluidic channels and are captured with patterned microstructures have limited throughput (ϕ < 5 mL h−1) and are susceptible to clogging, due to their microscale channels. The limited throughput and susceptibility to clogging of microscale devices have kept these approaches from being translated from the laboratory to many medical applications, where large volume samples, e.g. V > 10 mL of whole blood, must be processed rapidly (<15 minutes) to provide relevant point-of-care information. In particular, applications where extremely rare cells (e.g. CTCs, pathogens, stem cells) must be sorted from complex biological fluids (e.g. blood, sputum, environmental samples) require large volumes of unprocessed clinical samples to be sorted with the precision of microfluidics within timescales relevant to providing real-time information (T < 30 minutes). For example, using CTCs for the diagnosis of cancer requires the detection of extremely sparse cells (<1 CTC per mL) in volumes of blood >10 mL.10

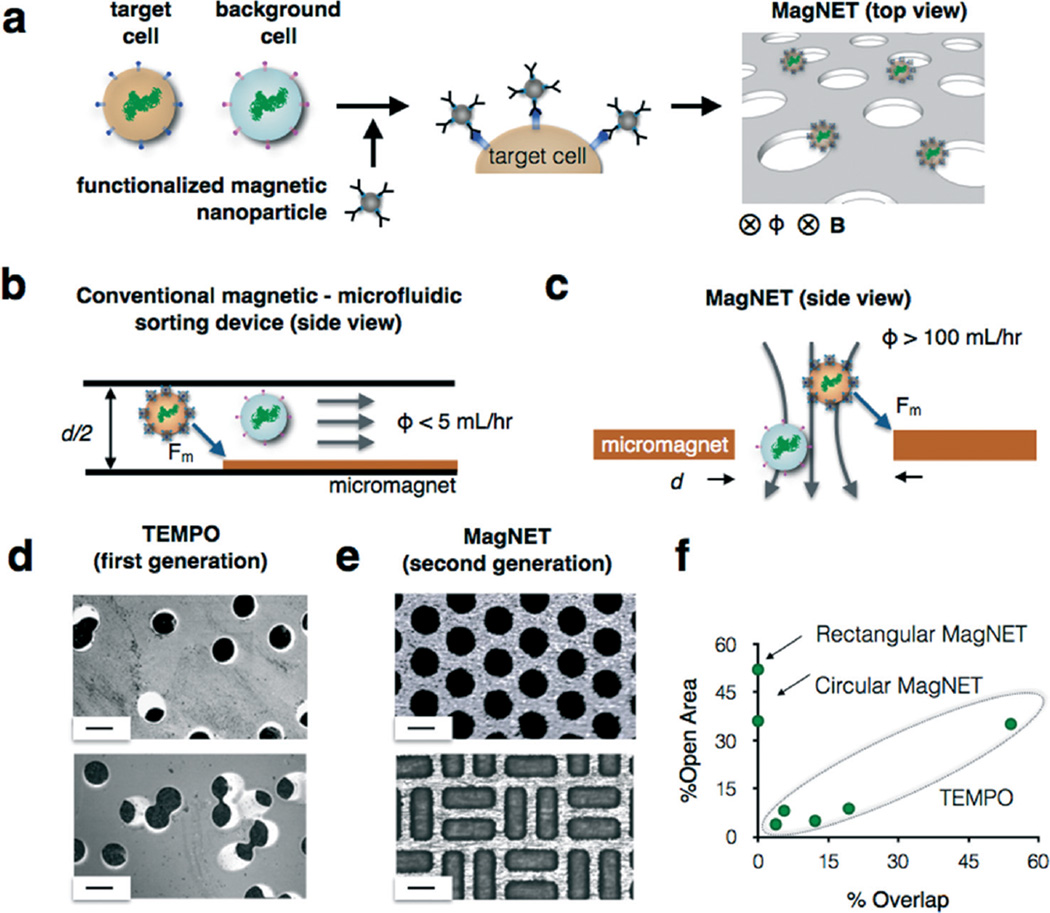

To address these challenges, we have developed a new approach to the micromagnetic separation of cells, the magnetic nickel iron electroformed trap (MagNET) (Fig. 1a). In contrast to lateral flow devices,6–8,10,11 our vertical flow design enables high flow rates (ϕ > 100 mL h−1) by having millions of micromagnetic traps operate in parallel. This improved throughput allows typical clinical samples (V > 10 mL of blood) to be processed in less than fifteen minutes, allowing precise microfluidic cell sorting to be used for rapid point-of-care diagnostics. Our design achieves this performance by rotating the conventional microfluidic geometry (Fig. 1b) by 90° to form magnetic traps at the edges of pores instead of in microfluidic channels (Fig. 1c). An external static field, provided by an inexpensive NdFeB magnet, magnetizes both the MNP labeled cells and the MagNET filter. This geometry allows millions of magnetic traps to be incorporated into a single centimeter sized device. Furthermore, the large density of micropores (ρ = 5 × 104 pores per cm2) reduces clogging from clinical samples, as the blockage of a few pores does not significantly change the device's behavior.12 The trapping of a cell in MagNET is based on a competition between the individual cell's drag force and its magnetic force as it passes through a magnetic micropore. Thus, the contrast in the magnetic trapping of targeted cells versus non-targeted cells is not affected by the concentration of cells. Unlike previous work, where magnetic micropores were defined using conventional microfabrication,13,14 we instead take inspiration from soft lithography15 and create a master that can be used repeatedly to economically produce replica permalloy membranes with lithographically defined micropores. The micropores on these 12 µm thick electroformed membranes can have arbitrary shape and position, allowing the device to be tailored for maximal capture efficiency and throughput. We demonstrate MagNET's capabilities by fabricating devices with both circular and rectangular pores and use these devices to rapidly (ϕ = 180 mL h−1) and specifically sort rare tumor cells (LOD = 3 cells per mL) from white blood cells.

Fig. 1.

High throughput immunomagnetic sorting with the magnetic nickel iron electroformed trap (MagNET). a. MagNET uses magnetophoretic traps to isolate cells specifically targeted with functionalized magnetic nanoparticles. This design enables high flow rates by having millions of micromagnetic traps operate in parallel. b. MagNET rotates the conventional microfluidic geometry by 90° to form magnetic traps at the edges of pores (c) instead of in microfluidic channels. d. Micrographs of Track Etched Magnetic microPOre (TEMPO) devices. In this approach as the density of micropores is increased so did the number of overlapped pores, which limited performance. Scale bar 30 µm. e. Micrographs of MagNET devices. In this approach density and the shape of the micropores could be tailored to maximize performance. Scale bar 30 µm. f. A graph summarizing the trade-off relationship between % open area and % overlap for both TEMPO and MagNET.

Our MagNET approach builds upon previous work from our lab, where track etching was used to fabricate magnetic micropores.12 The MagNET approach offers several important advantages over our previous approach, which we called Track Etched Magnetic microPOre (TEMPO). The TEMPO consists of an ion track-etched polycarbonate membrane coated with soft magnetic film, permalloy (Ni80Fe20). The main advantage of track etching is the ability to fabricate microscale pores over large areas (A > 1 cm2) at a cost <5¢ per cm2, much less than conventional microfabrication.12 MagNET conserves the advantages of TEMPO, and also addresses its two key weaknesses:

TEMPO's low cost fabrication comes at the expense of its ability to control the position or shape of the pores (Fig. 1d). The MagNET strategy solves this challenge, allowing pores to be created with arbitrary shape and position (Fig. 1e). The inability of TEMPO to control the position of the pores creates a tradeoff relationship between the density of the micropores and the fraction of pores that overlap with one another (Fig. 1f), which results in a tradeoff between the device's throughput ϕ and the capture efficiency of magnetically labeled cells ζ. The reason for this tradeoff is that as the fraction of open area is increased by increasing the density of micropores, the flow velocity through each pore decreases. As the flow rate decreases, the capture efficiency of each magnetic micropore increases, increasing the overall capture rate ζ. However, for TEMPO, as the density of track etched micropores increases, so does the fraction of pores that overlap (Fig. 1d). For pores that overlap, the effective pore diameter is increased and so fewer cells come in close proximity to the pore's edge to be trapped, and thus the overall capture efficiency ζ is reduced. MagNET's ability to control the position and shape of the pores allows this tradeoff relationship to be broken (Fig. 1f) and extremely high flow rates to be achieved ϕ > 100 mL h−1 without having to sacrifice capture rate ζ > 104.

While track etching allows the polycarbonate membranes in TEMPO to be fabricated at low-cost, the deposition of the magnetic film is expensive, slow, and requires specialized facilities.12 The MagNET strategy solves this challenge. Once the master is made, which requires a cleanroom and lithography equipment, subsequent replicas only require electroplating, which can be performed at high throughput and without specialized laboratory facilities.16 Moreover, the MagNET method allows thick permalloy films (12 µm) compared to thermal evaporation, which is practically limited to <1 µm, while also achieving consistent reproducibility of film thickness (±0.5 µm). The increased thickness of MagNET leads to an increased capture rate, due to both increased magnetic field gradients (Fig. 3b) and the formation of two traps in series for each pore: one on the top surface of the filter and one on the bottom (Fig. S2†).

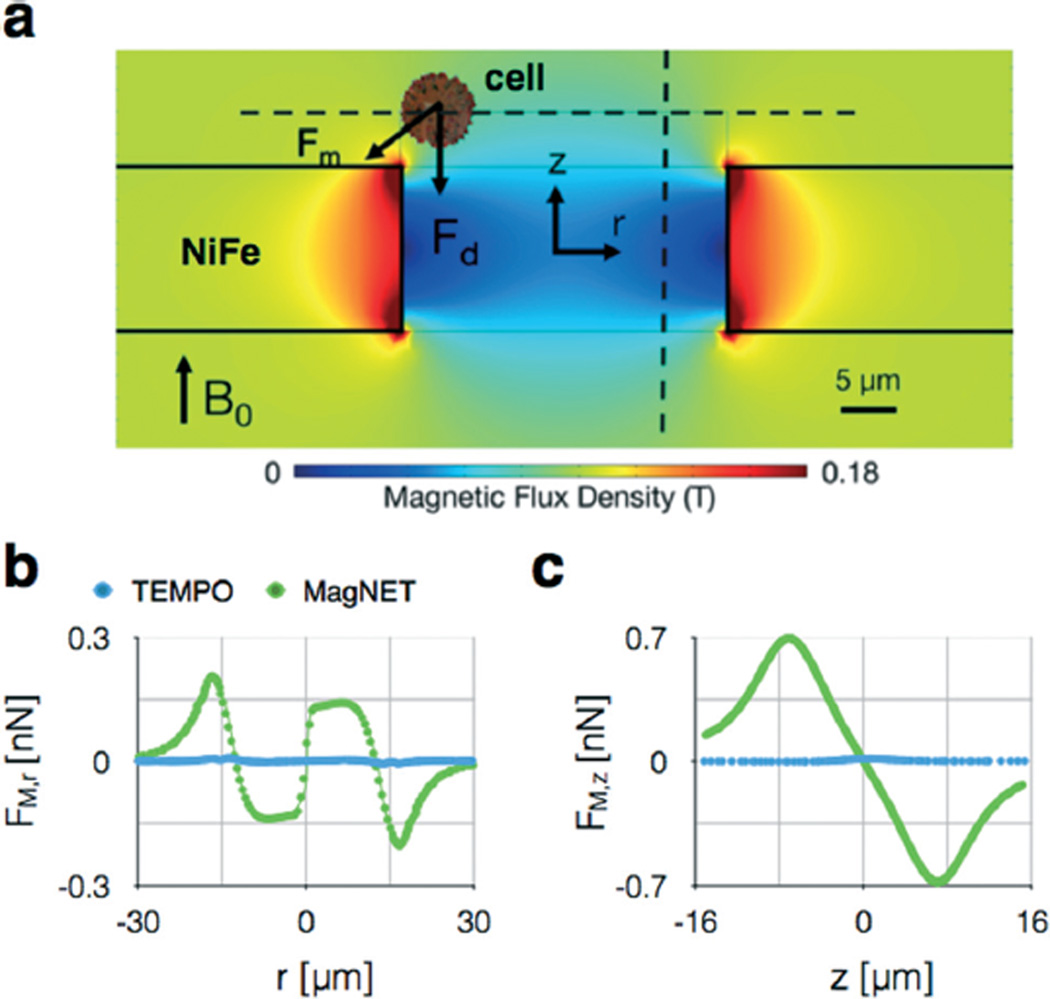

Fig. 3.

Finite element simulations of MagNET. a. The field strength |B| is plotted on the cross-section of an individual 30 µm pore. The magnetophoretic force Fm competes with drag force Fd to trap cells at the edge of the pore. b. The magnetophoretic force in the radial direction FM,r is plotted along r, one cell radius a = 5 µm above the MagNET's surface. c. The magnetophoretic force in the cylindrical direction FM,z is plotted along z, one cell radius a = 5 µm away the MagNET's edge.

Methods

Fabrication of the MagNET master

We take inspiration from soft lithography15 and create a master from which many replica MagNET devices can be produced using electroformation. Electroformation is a well-known process to form metal parts by electroplating onto a master (i.e. a mandrel), and subsequently removing the electroplated piece from the master to form a free-standing metal piece. Much work has been done to use this technique to form free-standing metal pieces with microscale features,17–19 but to our knowledge this work represents the first such work that creates a reusable microscale master to generate many replica devices. The creation of a reusable micro-scale master for electroformation comes with the following challenges: 1. A thin metal piece (i.e. 12 µm) must be removed from the master without tearing. 2. The master must be mechanically robust, such that the removal of the electroformed metal piece from the master does not cause the microscale features of the master to be destroyed.

To address these challenges, we made the following design choices. To remove the electroformed permalloy piece without tearing, we needed to find a metal substrate that has minimum adhesion to the electroformed material. We chose copper as a substrate because it is known to have low adhesion to permalloy.20 To allow the electroformed permalloy to be removed without destroying the master, we patterned the microscale features of the master in polyimide, which was adhered to a roll annealed copper substrate. The roll annealed copper on polyimide is more strongly adhered than is possible with spun-on photo-activated polymers (e.g. SU8),17–19 and so does not delaminate when the electroformed permalloy is removed. We used conventional microfabrication techniques to etch the polyimide to create the micropore pattern through which MagNET was electroformed.

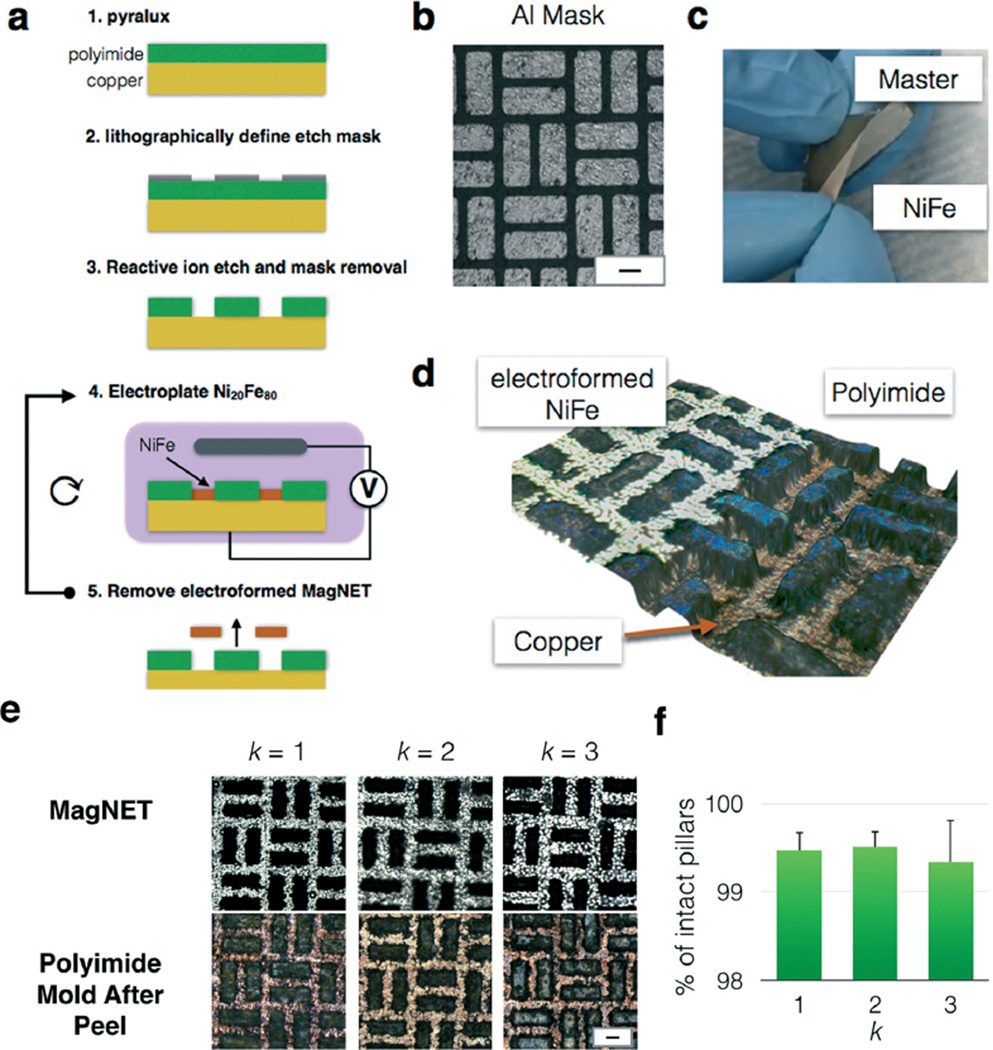

To fabricate the master for MagNET, we perform the following procedure (Fig. 2a). We begin with Pyralux AC181200R (Dupont), a substrate typically used for flexible electronics, where an 18 µm copper layer is roll annealed onto a 12 µm polyimide film. We adhere the Pyralux to a glass slide to prevent the film from wrinkling during processing. Next, a hard mask of aluminum (Al) is thermally evaporated (PVD75 E-beam/thermal evaporator) and patterned using conventional planar UV photolithography (Singh Center for Nanotechnology) (Fig. 2b). We use the same tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) solution (MF319, Microposit) to both develop the S1805 (Microchem) photoresist and chemically etch the Al mask. Finally, the unexposed photoresist is stripped in acetone. After patterning the Al hard mask, the polyimide is etched using inductively coupled plasma (ICP) etching.21–24 Whereas a pure plasma etch would result in isotropic etching, a combination of a plasma etch with ion bombardment provided an etch with a sufficiently anisotropic etch profile. Exposed regions of the copper without the polyimide pillars are used as zones for electroplating permalloy. Once the permalloy filter is >10 µm, the filter can be peeled off mechanically due to poor adhesion between the copper and electroplated permalloy20 (Fig. 2c). The Pyralux substrate facilitates the easy removal of the permalloy film. By gently flexing the substrate, the permalloy delaminates from the copper.

Fig. 2.

Master/replica fabrication of MagNET. a. Step by step fabrication of the master and subsequent replicas of MagNET. b. A micrograph of the lithographically defined aluminum mask. Scale bar 30 µm. c. Photograph of a replica MagNET being mechanically removed from its Master. d. Three dimensional optical micrograph of MagNET. In the region to the left, a MagNET has been electroformed. In the region to the right, the MagNET has been removed and the polyimide and copper master can be seen. e. Micrographs of the master and replica MagNETs after k replications. Scale bar: 30 µm. f. The fraction of damaged pillars was quantified after each replication, and there was no statistically significant change observed. (P ≫ 0.05). Error bars indicate standard error from the ratio of intact pores to total number of pores of different regions from the same device.

We optimized RIE conditions for the MagNET master using The Trion Phantom at University of Pennsylvania's Singh Center for Nanotechnology. After exploring a variety of combinations of pressures, RIE powers, RF powers, and gas flow rates, we found that O2/CF4 resulted in large undercuts in the polyimide and made etching 12 µm polyimide impractical since the undercut resulted in the erosion of the hardmask. O2/SF6 etching resulted in less undercut, as well as slower etch rates. The optimal recipe for the etching of the polyimide was with 40 sccm O2/10 sccm SF6/40 mT pressure/300 W ICP/50 W RIE for 50 minutes. The etch profile was characterized using profilometry and 3D imaging (Zeiss Smartzoom5 2D/3D).

Electroformation of MagNET

Permalloy was electroplated onto the MagNET master using nickel foil (1 mm thick, 99.5%, Alfa Aesar) as the anode in an electroplating solution containing 200 g l−1 NiSO4–6H2O, 8 g l−1 FeSO4–7H2O, 5 g l−1 NiCl2–6H2O, 25 g l−1 H3BO3, and 3 g l−1 saccharin (pH = 2.5–3).16 12 µm thick permalloy layer was deposited on the 3.8 cm [W] × 4.3 cm [L] master at 0.2 A for 45 min. The master was firmly attached to a flexible mylar support for plating. To peel off the filter, the mylar/Pyralux combination was flexed until the permalloy started to lift off at the corner. The permalloy was separated mechanically as shown in Fig. 2c. Once removed from the master, the free standing electroformed MagNET was then plated (Bright Electroless Gold, Transene) with approximately 100 nm of gold to passivate the surface.

Electroformation allows precise and repeatable control over film thickness. In prior work, permalloy has been electroplated with film thickness ranging from 500 nm to 5 µm in uniform, smooth layers (surface roughness <100 nm).25,26 To control the thickness of our electroformed film, we fixed the device area exposed to the electroplating solution, and then calibrated the deposition current and the deposition time to produce specific film thicknesses. We measured film thickness using a profilometer (KLA Tencor P7 2D profilometer). The variation of film thickness across individual devices was determined by measuring film thickness at N = 10 locations across the 3.8 × 4.3 cm2 film, resulting in a coefficient of variation of CV = 3.6%. The variation of film thickness across various devices was determined by measuring the average film thickness of N = 8 independently fabricated devices, resulting in a coefficient of variation between devices of CV = 3.3%. These measurements indicate that MagNETs can be fabricated with accurate and reproducible film thickness.

Device fabrication

The MagNET filter was incorporated into the device using a moisture-resistant polyester film (McMaster-Carr, 0.004″ thick) and a solvent-resistant tape (McMaster-Carr, adhesive on both sides). Multiple layers of the polyester film and the solvent-resistant tape were cut by a laser cutter (Universal Laser VLS 3.50) and assembled. For the device with multiple filters stacked in series, the filters were separated by the height of the polyester film (0.004″) and the tape (0.004″). An optically clear cast acrylic sheet (McMaster-Carr) was used as a reservoir, and the output was made using a blunt syringe tip (McMaster-Carr) epoxy-bonded to the device to pull the fluid from the reservoir. The design of each of the device layers, as well as a three dimensional rendering of the device, are shown in detail in Fig. S3.†

Results

Robustness of MagNET fabrication over multiple replications

One design challenge that we overcame in developing MagNET was to find a material that we could use to pattern the microscale features of our master that is not damaged during the removal of each electroformed MagNET replica. We found that spin-on polymers such as photoresists (SU8, S1818, SPR220) delaminated during mechanical peel off even after surface treatment to improve adhesion. Dupont's Pyralux – a material used for flexible circuit PCBs – consisting of 18 µm copper film roll annealed onto a 12 µm polyimide film proved to be perfect due to the polyimide layer's strong adherence to copper. To demonstrate the robustness of the MagNET master for reusability, we performed multiple cycles of plating and peeling, and for each cycle checked for any damaged pillars (Fig. 2e). Profilometer (KLA Tencor P7 2D profilometer) and 3D images (Zeiss Smartzoom5 2D/3D Optical Microscope) of the master confirmed that there was no structural damage during mechanical peel off, and that the electroformed filters were identical after multiple rounds of fabrication. The percent of damaged pores after rounds one, two, and three were 0.5%, and did not show a statistically significant increase after repeated use (P ≫ 0.05). To visually demonstrate the functionality of our fabrication process, we mechanically removed a MagNET such that a portion of the electroformed permalloy remained on the polyimide pillars, and subsequently imaged it (Fig. 2d and S1†) (Zeiss Smartzoom5 2D/3D Optical Microscope). In this image, the electroformed permalloy has been plated to the height of the pillars. Adjacent to this film, there is a region where the film has been peeled away and the copper and polyimide pillars are visible. The image demonstrates that the pillars are still intact, and at the same height as the permalloy, and thus the master is robust for multiple rounds of reuse.

Magnetic field finite element simulation

To aid in the design and characterization of the MagNET filter, we performed finite element simulations. We modeled MagNET as a circular d = 30 µm pore in a 12 µm thick permalloy film using a finite element simulation package (Comsol). We created a 2D axisymmetric model, containing one circular pore at the center of the permalloy film. The film is magnetized by a B = 0.4 T field in the cylindrical direction provided by centimeter-sized NdFeB magnet placed below MagNET. In addition to MagNET, we also modeled a TEMPO filter for comparison. The TEMPO model was identical to MagNET's except the thickness of the permalloy film was 200 nm. In these simulations, we used as our boundary conditions that at distances far from MagNET or TEMPO, the magnetic field dropped to zero.

To calculate the magnetophoretic force Fm = (m·∇) B on a cell as it passes through MagNET, we combined the finite element field simulations described above with a simplified model for a cell. The total magnetic moment of the cell was calculated to be proportional to the number of magnetic nanoparticles n, each with a magnetic moment mp = 106 Bohr magnetons, with the assumption that the external magnetic field was sufficient to fully magnetize the beads.24 Due to the low Reynold's number regime of flow through the micropore, the mass of the cell does not play a role in determining the cell's behavior. The total number of particles per cell was assumed to be 104 particles. There are a total of >105 CD45 receptors on a leukocyte.6 The assumed number of particles (104) corresponds to 6.2% coverage of the surface of the cell, and thus would not result in significant steric hinderance. We assumed the cell to have a radius a = 5 µm and the particles to have a radius b = 25 nm. We calculated the magnetic force experienced by the cell, Fm = ([mp*n]·∇) B, as the sum of the magnetic force experienced by all of the beads bound to the cell.

We calculated and plotted the radial force Fr experienced by the cell at one cell radius a = 5 µm above the filter. Additionally, the force in the cylindrical direction Fz on the cell was calculated and plotted along a line one cell radius a = 5 µm away the filter edge. The magnetophoretic force is opposed by a drag force, which can be calculated using Stokes equation Fd = 6πηav, where ηwater = 0.8 mPa s−1, a = 5 µm for a cell. The average flow velocity in the pore vavg = ϕ/(nporeApore), where npore is the total number of pores and Apore is the cross sectional area of the pore. We calculated the maximum flow rate ϕ at which the magnetic trapping force Fm would still be greater than the drag force Fd, and the cell would remain trapped on the edge.

The results of the finite element simulations were used to choose design parameters, such as the pore diameter, and to guide us in approaches to further improve the throughput and enrichment of our device. Fig. 3a shows the simulated magnetic flux density around the edge of the pore. The magnetic flux density drops rapidly away from the edge of the pore, leading to strong gradients and magnetic forces at this region. Based on this simulated field, we calculated the radial and vertical forces experienced by a cell as it moves through the pore. The radial force, which pulls cells to the edge of the pore, was plotted 5 µm above the MagNET's surface (Fig. 3b). The force has a maximum magnitude of Fr = 266 pN at the edge of the pore and drops rapidly in distance r from the pore's edge. Thus, we can improve the device's performance by making the pore as small as possible, as that will force cells to come into close proximity of the regions where the magnetic force is the strongest. However, the pores must be large enough that we do not capture off-target cells based on their size. The max Fr and Fz are ~10× and ~50×, respectively, larger for MagNET than TEMPO, demonstrating that the thicker metal film allows stronger trapping forces. Once a cell is translated to the pore's edge, the magnetic force Fz opposes the drag force Fd, and determines whether the cell will stay in the trap or not. The magnetophoretic force (Fig. 3c), at one cell radius a = 5 µm away from the filter, is Fz = 707 pN. For the device described above (A = 6.2 cm2), the magnetic force will exceed the drag force up to extremely large flow rates ϕ > 1000 mL h−1. Thus, the performance of the device will be limited solely on what fraction of cells make it to the pore's edge. And, based on this fact, we predict that device performance can be improved, even at flow rates ϕ ≫ 100 mL h−1, by stacking multiple filters in series to give cells multiple chances to be trapped.

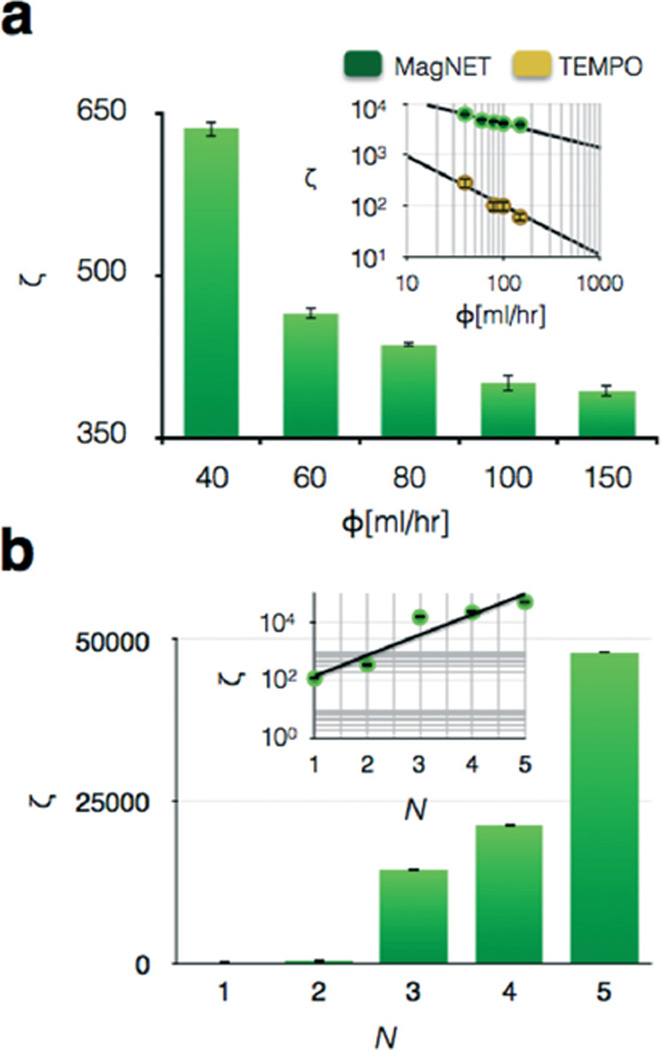

Characterization of MagNET's using a suspension of microbeads as a model sample

Before testing the MagNET's capability to sort cells, we first tested it with magnetic and non-magnetic polystyrene beads that have well characterized, homogenous properties. We used 1 µm pink fluorescent magnetic beads (FCM-1058-2, Spherotech) and 1 µm yellow fluorescent polystyrene beads (F13081, Invitrogen). We first compared the performance of MagNET to TEMPO, where both filters had an area of A = 6.2 cm2. The input to each device contained a 100 : 1 ratio of magnetic to non-magnetic beads. To characterize the capability of these devices to selectively sort magnetic beads, we calculated an enrichment factor ζ = (C1p/C1m)/(C0p/C0m), at different flow rates Φ, where C0p and C1p are the numbers of non-targeted beads before and after sorting respectively, and C0m and C1m are the numbers of targeted beads before and after sorting respectively. We found that as flow rate increased, the enrichment dropped as a power law (Fig. 4a). At all flow rates the enrichment of MagNET was >30× the enrichment of TEMPO. One of the reasons for MagNET's enhanced performance is that, in contrast to TEMPO where beads are captured on only one side of the filter (NiFe deposited), on MagNET the beads were captured both on the front and back side of the 12 µm thick MagNET layer. By forming two traps, on the top and bottom surface of MagNET, the capture efficiency is increased by providing a second chance for cells missed by the trap on the top surface of MagNET to be captured (Fig. S2†). Moreover, we demonstrated that enrichment could be further improved by stacking multiple MagNET filters in series (Fig. 4b). By increasing from N = 1 to N = 5 at Φ = 150 ml h−1, enrichment was improved ~1000×, allowing high enrichment (ζ > 5000) to be achieved even at exceedingly high flow rates Φ = 150 mL h−1. As the filters are vertically stacked, the subset of the cells missed by the previous filter can be captured on the next filter, which leads to an exponential increase in the enrichment ζ ∝ ζ0 N, where ζ0 is the enrichment of one filter (Fig. 4b – inset).

Fig. 4.

Characterization of the MagNET using microbeads. a. 1 µm diameter magnetic polystyrene microbeads were sorted from non-magnetic 1 µm polystyrene microbeads using MagNET. The enrichment of the non-magnetic beads ζ is plotted vs. flow rate. Inset: Enrichment vs. flow rate on a log–log plot for both MagNET and TEMPO. At all flow rates the enrichment of MagNET was ζ > 30× the enrichment of TEMPO. The error bars indicate standard error from replicates from flow cytometry measurement. b. As N filters are vertically stacked the enrichment at Φ = 150 ml h−1 was improved ~1000×. Inset: Enrichment ζ vs. Φ on a log-linear plot, shows that enrichment ζ scales exponentially with the number of filters N. The error bars indicate standard error from replicates from flow cytometry measurement.

Reusability of the electroformed device

In addition to the reusability of the master, MagNET can also be reused since it consists of only metal (NiFe passivated with gold) and can be cleaned with aggressive mechanical agitation. Unlike conventional micro-magnetic sorting devices, where a magnetic film is adhered to a substrate, in MagNET there is no risk of delamination of the metal layer from the substrate during cleaning. Additionally, aggressive solvents can be used that would not be compatible with a polymer-based device (e.g. acetone with PDMS). To test the reusability of MagNET, we compared the performance of a previously used MagNET to a newly fabricated device. At 6 different flow rates, the enrichment of the used MagNET was not statistically significantly different from the newly fabricated device (P ≫ 0.05).

Characterizing MagNET's ability to sort tumor cells from leukocytes

To demonstrate the utility of our chip to perform highly specific cell sorting, we used MagNET to isolate spiked tumor cells from a large background of leukocytes. The detection of rare circulating tumor cells (CTCs) (<100 cells per mL) has demonstrated great potential to diagnose and monitor cancer and has gained enormous attention in the field of microfluidics.7,8,10,11,27,28

MagNET's highly specific capture of cells at ultra-high flow rates offers an important new tool for the study of CTC biomarkers as well as their translation to the clinics. While many ingenious microfluidic devices have been used with great success to sort CTCs,2,7,9 there is currently a mismatch between the throughput of microfluidic devices (ϕ ≅ 1 mL h−1) and the large sample volume of blood (V ~ 20 mL) necessary for ultra-rare cell detection. This mismatch leads to run times unsuitable for practical use (T > 10 h). MagNET, with its ϕ = 100 mL h−1 flow rates, can process 20 mL of whole blood in only twelve minutes. In this demonstration, rather than using MagNET to trap tumor cells based on one of their heterogenous properties, we instead use negative selection, wherein the cells that are easily identified as not being tumor cells are removed from suspension (i.e. white blood cells) to create a concentrated population enriched for potential CTCs.7,29 Because CTCs are present in clinical samples at a ratio of approximately 1 tumor cell for every 1 million leukocytes, the high enrichment of MagNET (ζ ~ 104) is necessary to create enriched populations (1 tumor cell for every 100 leukocytes) that can be practically analyzed. And, MagNET is capable of even greater enrichment ζ for applications that require high purity, e.g. molecular analyses, by either decreasing the flow rate ϕ or increasing the number of filters N.

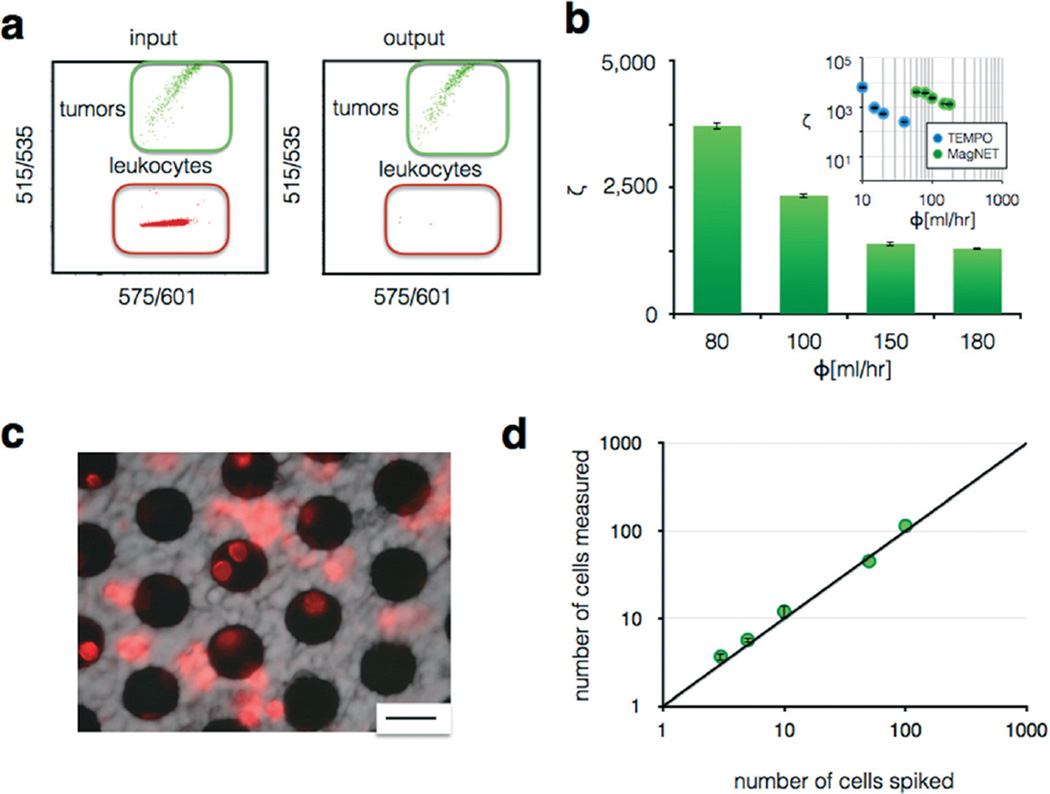

To test our chip's ability to sort rare CTCs from leukocytes, a known number of cells from pancreatic cancer cell line (PD7591) were spiked into a background of leukocytes (Jurkat), and the enrichment of CTCs relative to leukocytes was quantified. Cancer cells and leukocytes were stained with different fluorescent dyes, green (CellTracker Green, Invitrogen) and red (CellTracker Red, Invitrogen) respectively, and a suspension of 100 : 1 of leukocytes to cancer cells was fed into the device. The leukocytes were labeled with CD45 functionalized MNPs (Miltenyi) to be captured on MagNET. Both the input and output were measured using flow cytometry, and the enrichment ζ quantified (Fig. 5a). The magnetically labeled leukocytes were captured on MagNET and only a very small fraction (<0.04%) were missed, even at extremely high flow rates ϕ = 100 mL h−1 using N = 4 MagNET filters in series (Fig. 5b). MagNET's performance sorting tumor cells from leukocytes was directly compared to TEMPO's (Fig. 5b – inset), which showed that MagNET matched TEMPO's enrichment at 5× the flow rate of TEMPO. A fluorescence micrograph of MagNET after sorting shows leukocytes, stained in red, captured at the edge of the pores of where the magnetic field gradients are the largest, confirming that the cells were captured due to magnetic forces (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Characterizing MagNET's ability to sort tumor cells from leukocytes. a. Cytometry quantified cell populations before and after filtration. b. Very high enrichment ζ was achieved at flow rates Φ > 80 mL h−1 using N = 4 filters. Inset: Enrichment vs. flow rate on a log–log scale for the sorting of leukocytes from tumor cells using both MagNET and TEMPO. The error bars indicate standard error from replicates from flow cytometry measurement. c. A fluorescence micrograph showing leukocytes, stained red, trapped on the MagNET filter. Scale bar: 30 µm. d. Titration of cultured cells into whole blood measured using MagNET, for negative selection of leukocytes, combined with a sized-based filter that concentrated the tumor cells into a small field of view (3 × 3 mm2) were enumerated using microscopy. A limit of detection LOD < 3 cells in a 1 mL suspension was achieved at a flow rate of Φ = 80 mL h−1.

To test the sensitivity of our chip to rare cells, we challenged our device with an in vitro model for CTCs, wherein we spiked a known number of cultured pancreatic cancer cells (PD7591) into a background of leukocytes (Jurkat) and enumerated the number of recovered tumor cells. To quantify the number of CTCs, a size-based filter that consisted of a nucleopore track-etched polycarbonate membrane was incorporated into our device downstream of MagNET. The size-based filter had a size of only 3 × 3 mm2, allowing rapid enumeration with microscopy. On this filter, captured potential CTCs could be imaged using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Leica DM750M). This device used N = 4 MagNET filters in series, with an area of 6.2 cm2. A titration of varying numbers of tumor cells spiked into a background of Jurkat cells was prepared using serial dilution and then ran through our device (Fig. 5d). The enumeration of these spiked cells agreed with expected cell numbers (R2 = 0.99) over a dynamic range of 3 to >100 cells. A limit of detection (LOD) of <3 cells in a 1 mL suspension was achieved at a flow rate of 80 mL h−1.

Discussion

MagNET offers a new approach to immunomagnetic separation that can be performed at extremely high flow rates (ϕ > 100 ml h−1) without sacrificing the high sorting efficiency (ζ > 104) typical of microfluidics. Additionally, we have developed a fabrication strategy for MagNET that can produce these high performance, microfabricated devices without specialized facilities, enabling MagNET to be manufacturable for applications such as low-cost medical diagnostics.30 In this paper we demonstrated the utility of MagNET to sort rare tumor cells from blood cells for CTC detection. However, the approach is broadly applicable to any application that requires highly specific sorting of rare cells from large volume unprocessed samples, such as the diagnosis of infectious disease, environmental sensing, cancer biology, and stem cell research.9,31

Our MagNET approach to rapidly sort immunomagnetically labeled cells from unprocessed samples is well suited for incorporation into integrated microfluidic systems. For example, MagNET can be used to perform negative selection upstream of ultrasensitive, low throughput single cell measurements.8,30,31 By removing the vast majority of background cells, it can improve the effective throughput of these single cell detection modalities by orders of magnitude. Additionally, due to the high enrichment ζ of MagNET, it can isolate rare cells with the purity necessary for downstream molecular analysis, such as quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), sequencing, or nanodevice (e.g. nanowire, graphene, etc.) sensing.10,32–35 In addition to negative selection, MagNET can also be used for positive selection. The MagNET filter has the advantage that when the external NdFeB magnet is removed, the magnetic force disappears, and the trapped cells can be released for downstream analysis. The viability of trapped cells in the MagNET has not yet been evaluated, but traps with similar forces have been demonstrated to keep trapped cells viable.36,37

The master/replica electoformation fabrication strategy developed in this paper has uses beyond the cell sorting highlighted in this manuscript. It also has broad applications for the manufacturing of electroformed microscale devices. There have been many previous approaches to electroform metal pieces with microscale features for a variety of applications,17–19,38,39 but our MagNET technology represents the first such work that creates a reusable microscale master to generate many replica devices. There have been several recent, particularly exciting, applications that use electroformed micromagnets. One publication combined electroformation with a novel process to transfer NiFe micro-scale structures to flexible PDMS membranes to confer magnetic properties to substrates such as coverslips and eppendorf tubes.38 In another example, electroformed NiFe microstructures were created to generate large magnetic ratcheting forces to trap and translate cells in a microfluidic channel labeled with magnetic nanomaterials.39 Our reusable master/mold technique can reduce the cost of fabrication of such technologies by eliminating the need to do costly lithography to create each device, and thus aid in the translation of these emerging technologies to commercial use. Our MagNET fabrication strategy offers a general approach to produce low-cost devices at high production rates for a wide range of microchemical systems (MEMS), including microsensors, microactuators, and microswitchers.17

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work would not have been possible without the help of Dupont, which provided the Pyralux substrate for research purposes. We would like to thank the Stanger Lab, in particular Neha Bhagwat for the pancreatic and Jurkat cell lines. We would like to thank the Mark Allen Lab, in particular Minsoo Kim, for advice in creating the electroplating formulations. We would like to thank the Singh Center Staff, in particular Eric Johnston, Meredith Metzler, Gerald Lopez, and Noah Clay, for their advice in fabricating the master.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c6lc00487c

References

- 1.Chen Y, et al. Lab Chip. 2014;14:626–645. doi: 10.1039/c3lc90136j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagrath S, et al. Nature. 2007;450:1235–1239. doi: 10.1038/nature06385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallacher L, et al. Blood. 2000;95:2813–2820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ardehali R, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:3405–3410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220832110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miltenyi S, Muller W, Weichel W, Radbruch A. Cytometry. 1990;11:231–238. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990110203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pamme N. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012;16:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.05.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozkumur E, et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:179ra47. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Issadore D, et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:141ra92. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muluneh M, Issadore D. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2014;66:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang JM, Casavant BP, Beebe DJ. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:141ps13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen P, Huang YY, Hoshino K, Zhang JXJ. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8745. doi: 10.1038/srep08745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muluneh M, Shang W, Issadore D. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2014;3:1078–1085. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Earhart CM, Wilson RJ, White RL, Pourmand N, Wang SX. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2009;321:1436–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2009.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Earhart CM, et al. Lab Chip. 2014;14:78–88. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50580d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitesides GM, Ostuni E, Takayama S, Jiang X, Ingber DE. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2001;3:335–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.3.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park J-W. PhD Thesis at Georgia Institute of Technology. 2003. Core lamination technology for micromachined power inductive components. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGeough JA, Leu MC, Rajurkar KP, De Silva AKM, Liu Q. CIRP Annals-Manufacturing Technology. 2001;50:499–514. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makarova OV, et al. Sens. Actuators, A. 2003;103:182–186. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosokawa M, et al. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:6629–6635. doi: 10.1021/ac101222x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okamoto N, Wang F, Watanabe T. Mater. Trans. 2004;45:3330–3333. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turban G, Rapeaux M. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1983;130:2231–2236. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mimoun B, Pham HTM, Henneken V, Dekker R. J. Vac. Sci. Technol., B. 2013;31:021201. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SH, Lee CH, Ahn JH. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2002;40:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buder U, von Klitzing J-P, Obermeier E. Sens. Actuators, A. 2006;132:393–399. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim M, Kim J, Herrault F, Schafer R, Allen MG. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2013;23:095011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor WP, Schneider M, Baltes H, Allen MG. Solid State Sensors and Actuators, 1997. TRANSDUCERS '97 Chicago., 1997 International Conference on. 1997;2:1445–1448. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cristofanilli M, et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351.8:781–791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parkinson DR, et al. J. Transl. Med. 2012;10:138. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung J, et al. Biomicrofluidics. 2013;7:054107. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Issadore D, Westervelt RM. Point-of-care Diagnostics on a Chip. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dharmasiri U, Witek MA, Adams AA, Soper SA. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2010;3:409–431. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.111808.073610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaffer SM, Joshi RP, Chambers BS, Sterken D, Biaesch AG, Gabrieli DJ, Li Y, Feemster KA, Hensley SE, Issadore D, Raj A. Lab Chip. 2015;15:3170–3182. doi: 10.1039/c5lc00459d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wheeler AR, Throndset WR, Whelan RJ, Leach AM, Zare RN, Liao YH, Farrell K, Manger ID, Daridon A. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:3581–3586. doi: 10.1021/ac0340758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lohr GJ, et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32(5):479–484. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng G, Patolsky F, Cui Y, Wang WU, Lieber CM. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1294–1301. doi: 10.1038/nbt1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vieira G, et al. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;103(12):128101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.128101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nilsson J, Evander M, Hammarström B, Laurell T. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2009;7:141–157. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tseng P, et al. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:1083–1089. doi: 10.1002/adma.201404849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murray C, et al. Small. 2016;12:1891–1899. doi: 10.1002/smll.201502120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.